Abstract

Objective

To examine the association of blood pressure (BP) with incident Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia.

Methods

This work is based on a longitudinal, cohort study of 18 years, the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP) performed in 2,137 participants (55% African American [AA]) with systolic BP measured about 8.1 years before incident AD dementia.

Results

The association of BP with risk of AD dementia was U-shaped, with the lowest risks of AD dementia near the center of the SBP and DBP distributions, and modestly elevated risk at lower BPs, and greater risk at higher BPs. The degree of U-shape and the range of lowest risk (threshold ranges) varied with antihypertensive medication use and presence of the APOE ε4 allele. The U-shape was most prominent for the subgroup not taking anti-hypertensive medications and having an APOE ε4 allele. At higher BPs, those having the APOE ε4 allele and not receiving anti-hypertensive medication were at greater risk of AD dementia than other groups: The risk of incident AD dementia increased by 100% (RR=2.00, 95% CI= 1.70, 2.31) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP above 140 mmHg. For DBP, the risk of incident of AD dementia increased by 57% (RR=1.57, 95% CI= 1.33, 1.86) for every 5mmHg increase in DBP above 76 mmHg.

Interpretation

The BP-risk of AD dementia association is U-shaped, with elevated risk at lower and higher BPs. People having the APOE ε4 allele and not receiving antihypertensive medication with higher BPs have notably elevated risk of AD dementia.

INTRODUCTION

The association of blood pressure (BP) with risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD dementia) remains unclear despite systematic reviews1,2 and extensive study, with studies reporting greater risk of AD dementia with higher BP,3,4 lower risk,5,6 and null results in older adults.7,8 The issue is of great public health importance to the aging population because of the high prevalence of hypertension, the widespread availability of effective antihypertensive therapy, and the paucity of potentially reversible risk factors for AD dementia, and the increasing magnitude of AD dementia as a public health problem with continued rapid growth of the oldest population age groups.9

METHODS

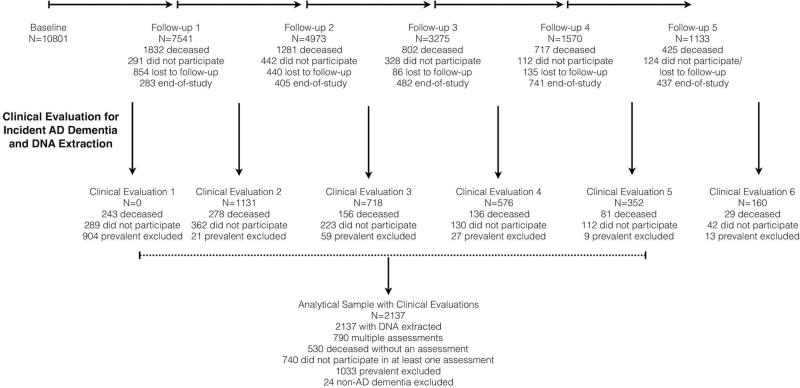

The Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), a longitudinal population-based study of AD dementia and other health conditions among adults aged 65 years and older conducted from 1993–2012, enrolled 78.7% of all residents over 65 years of age from a geographically defined biracial community of African Americans (AAs) and non-Hispanic European Americans (EAs). Residents who reached 65 years of age in subsequent years were enrolled in successive age cohorts. Cognitive tests were administered during population interviews conducted in participants’ homes in approximately three-year cycles for up to six cycles over 18 years. Independent detailed clinical evaluations for AD dementia were performed using a stratified random sample of participants at baseline and at three-year intervals thereafter.10 At the end of each cycle of population data collection, individuals were selected for a detailed clinical evaluation of incident AD dementia with a probability-based sampling weight. The use of sampling weights ensured that our clinical sample was representative of the population sample from which it was drawn and accounts for missing data due to demographic characteristics. A detailed flow chart of individuals selected for clinical evaluation of incident AD dementia is shown in Figure 1. In essence, 2,137 individuals selected for clinical evaluation of incident AD dementia were cognitively intact during the baseline assessment and eligible to be a part of this investigation. During these clinical evaluations, DNA samples were also extracted and frozen for genotyping at a later date. The Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study. All participants provided signed, written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Selection of Clinical Evaluation for Incident AD Dementia and DNA Extraction from the Population Sample

Note: End-of-study: Successive age cohorts who had less follow-up than the original cohort

Clinical Diagnosis of AD dementia

Clinical evaluations were structured and uniform with examiners blinded to population interview cognitive testing and sampling category.10 It included a structured medical history, neurological examination, and a battery of 19 cognitive function tests. A board-certified neurologist, who was unaware of previously collected data, diagnosed dementia and AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria.11 These required a history of cognitive decline and evidence of impairment in two or more cognitive domains, one of which had to be memory.

Measurement of BP, Antihypertensive Medications, and Other Variables

BP was measured using mercury sphygmomanometers (Baumonometer) according to the protocol of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program12 from 1993 through July 2006 (baseline BP measurements for 2085 subjects). Subsequently BP was measured using digital oscillometric devices (Omron HEM-780, Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, IL) (baseline BP measurements for 82 subjects). Each measurement was the average of two BP readings at baseline approximately 8.1 (SD=3.8) years before clinical diagnosis for incident AD dementia during the baseline assessment at the beginning of the study. An indicator variable for digital BP measurement to capture device variation was used in our analysis. At each in-home interview, use of all medications over the preceding two-week period was ascertained by direct inspection; medications were then classified using the MediSpan system, which facilitated grouping by biologically active agents, including individual ingredients of combination products, permitting efficient identification of antihypertensive medications. APOE ε4 genotypes were ascertained using two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): rs7412 and rs429358. These SNPs were genotyped in each subject at the Broad Institute for Population Genetics using the hME Sequenom MassARRAY® platform. Genotyping call rates were 100% for SNP rs7412, and 99.8% for SNP rs429358. Both SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with p-values of 0.0833 and 0.7925, respectively. Based on these two SNPs, we created an indicator variable for participants with one or more copies of the APOE ε4 allele. Race/ethnicity was measured using the 1990 U.S. Census Question; education was measured as the number of years of formal schooling completed. The presence of heart disease and diabetes were assessed by self-report using questions from the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were stratified by antihypertensive medication use and the presence of the APOEε4 allele, and presented using means and standard deviations for continuous measures, and frequencies and percentages for categorical measures. Baseline characteristics were compared using a two-sample t-test and a chi-squared test statistic depending on the type of measure. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the relative risk of AD dementia using time from baseline to clinical diagnosis of AD dementia, and a censoring variable denoting the end of observation or clinical diagnosis of AD dementia. All models were adjusted for age (centered at 75), sex (male vs. females), race (AAs vs. non-AAs), education (centered at 12), and an indicator for BP measurement instrument. In a sensitivity analysis, we included additional confounders, such as, baseline measures of BMI<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, 30+, overall dietary quality, current and past smoking status, grams of alcohol and caffeine intake, and hours of physical activity, and number of depressive symptoms to examine if the association of SBP and DBP with incident AD in APOE and BP medication groups were independent of the confounders.

A visual inspection of the probability of incidence AD dementia against the levels of SBP and DBP was performed to assess the degree of association non-parametrically prior to any regression analysis. The number of individuals with incident AD dementia divided by the number of individual in every 10-mmHg intervals was plotted against the midpoint of the interval. Based on these non-parametric plots, we visually inspected the degree of association prior to our regression-based approach.

For regression models, first, a linear risk function was used to examine the associations of SBP and DBP with the risk of developing AD dementia. Second, a smoothed penalized quadratic spline of an evenly spaced basis function for BP was used to examine the change in log hazard function over the range of SBP.13 The regression terms for the spline basis function of BP was used to examine the minimum of the log hazard function over the values of BP to estimate the threshold-like value. A model-based resampling algorithm for right censored data was used to estimate the confidence intervals around the minimum value of the log hazard function. Since the tails of the risk function, at high values of SBP and DBP could be influenced by extreme observations, and since only a small fraction, generally less than 3%, had such high and low BPs, we truncated low and high SBPs at 100 and 220 mmHg, respectively; this range was set at 50–110 mmHg for DBP. A quadratic spline model had higher log pseudo-likelihood values than a linear model in most of our models. A sensitivity analysis for the quadratic spline model was performed by fitting a cubic spline with two unknown knots, which did not improve our model fit. We used a bootstrap resampling technique to account for fitting of the hazard model and selection of the minimum log hazard ratio to obtain point estimates and confidence intervals of the log hazard ratios for our sampling weight-based selection process. The single knot of the quadratic spline model, where the risk function changes direction was termed as optimal value, and confidence intervals for these optimal values were also estimated using bootstrap approach. Bootstrap-based pointwise standard errors were used to estimate confidence intervals around the hazard curves and to test optimal values and hazard ratios between APOE and BP groups. The analysis was stratified by the use of antihypertensive medication and the presence of the APOEε4 allele, and performed using coxph, pspline, and censboot functions in R program.

Role of the funding source

The study sponsors had no active role of the conduct of the study, including the study design, analysis, interpretation, writing, and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

RESULTS

In a stratified random sample of 2,137 community residents over the age 65 who underwent clinical evaluation for AD dementia, (Table 1) the average age was 73.1 years with average education was 13.0 years, mostly women (63%) and a higher fraction of AAs (55%). About 11% also reported heart disease and 6% reported diabetes. Average BPs were 138.5 mmHg (SBP) and 77.2 mmHg (DBP) with 57% using one or more antihypertensive medications and 31% had at least one APOEε4 allele, and 437 (20%) had developed AD dementia at clinical evaluation. Participants using antihypertensive medication reported having a higher SBP, education, and self-report of heart disease or diabetes, but not having an APOEε4 allele. No significant difference in systolic (p=0.24) and diastolic (p=0.55) BP was found between participants with and without the APOEε4 allele.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 2137 Participants Who Subsequently Underwent Clinical Evaluation for Incident AD dementia

| All Participants Mean (SD) |

No BP Meds. Mean (SD) |

BP Meds. Mean (SD) |

No APOE ε4 Allele Mean (SD) |

Any APOE ε4 Allele Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N= 2137 | N=913 | N=1224 | N=1330 | N=608 | |

| Age (years) | 73.1 (5.9) | 73.1 (6.0) | 73.1 (5.8) | 73.4 (5.9) | 72.3 (5.5) |

| Education (years) | 13.0 (3.4) | 13.2 (3.5) | 12.8 (3.3) | 12.9 (3.3) | 13.0 (3.4) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 138.5 (18.5) | 135.6 (17.8) | 140.6 (19.5) | 139.1 (19.1) | 137.9 (18.9) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 77.2 (10.5) | 76.8 (10.2) | 77.5 (10.8) | 77.4 (10.4) | 77.1 (10.9) |

| African Americans, % | 1165 (55%) | 438, 48% | 727, 59% | 712, 54% | 388, 64% |

| Females, % | 1331 (63%) | 546 (60%) | 785 (64%) | 828 (62%) | 377 (62%) |

| APOE, % | 608 (31%) | 245 (29%) | 363 (33%) | -- | -- |

| BP medication use, % | 1224 (57%) | -- | -- | 744 (56%) | 363 (60%) |

| Heart disease, % | 243 (11%) | 39, 4% | 204, 17% | 160 (12%) | 63 (10%) |

| Diabetes, % | 134 (6%) | 23, 3% | 111, 9% | 87 (7%) | 36 (6%) |

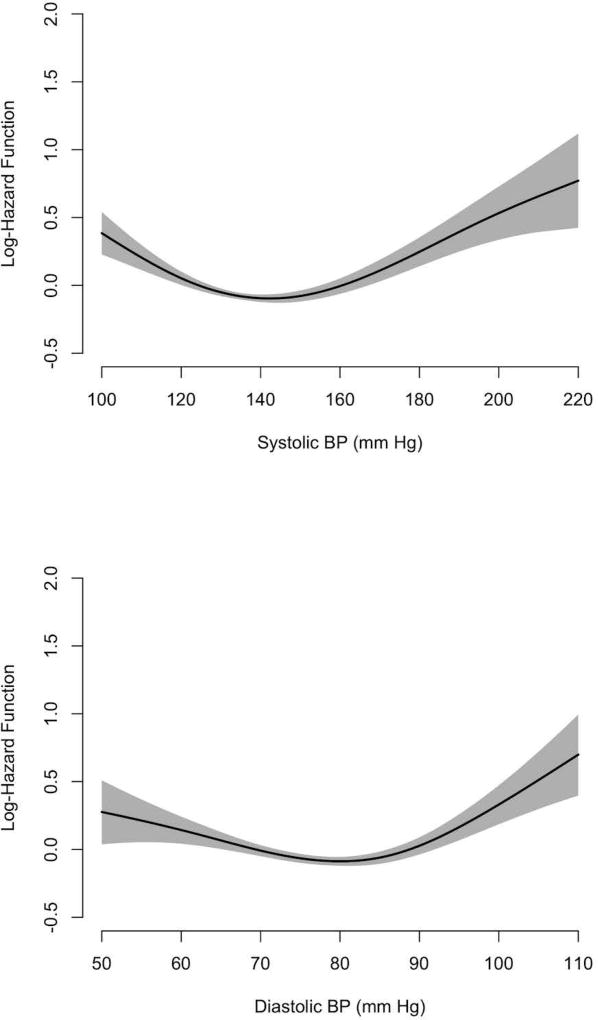

In general, our overall analysis found the association of systolic and diastolic BP with the risk of incident AD dementia to be U-shaped and asymmetric (Figure 2). The lowest risk of AD dementia was near the center of the SBP and DBP distributions with lower BP associated with modestly elevated risk of incident AD dementia, and higher BPs with greater elevation of risk.

Figure 2.

Log Hazard Function for the Associations of Systolic and Diastolic BP with Clinical Diagnosis of Incident AD dementia

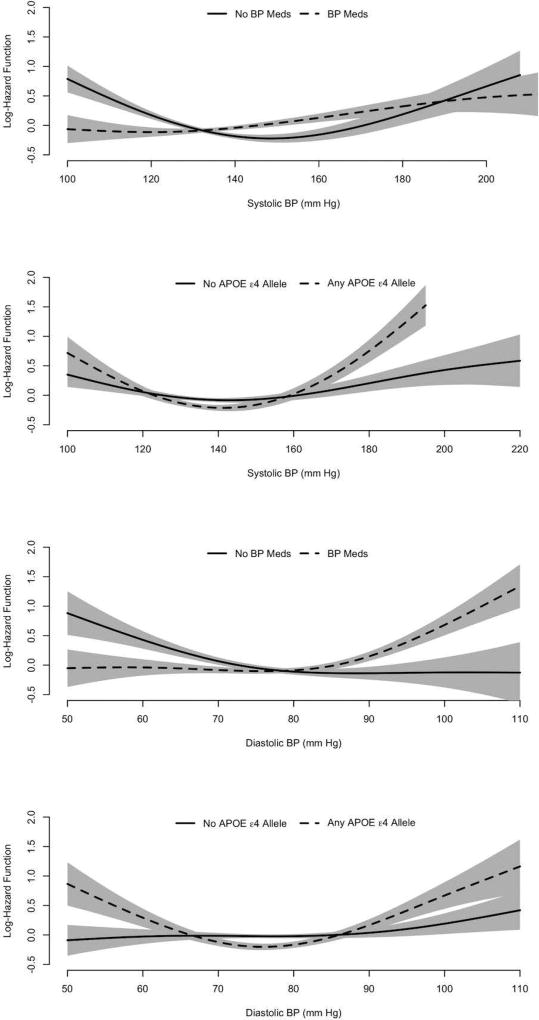

Modification by the APOEε4 Allele

For subjects having the APOE ε4 allele, the risk of incident AD dementia appeared to be more elevated at both low and high BPs than for those without this allele for both SBP and DBP (Figure 3). For people with one or more copies of the APOEε4 allele (Table 2) and higher BPs, the relative risk (RR) of incident AD dementia was substantially higher: For SBP, the risk of AD dementia increased by 43% (RR=1.43, 95% CI= 1.29, 1.59) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP above 141 mmHg. For DBP, the risk of AD dementia increased by 32% (RR=1.32, 95% CI= 1.20, 1.44) for every 5 mmHg increase in DBP above 76 mmHg. For people with the APOEε4 allele and lower range of BPs, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 30% (RR=0.70, 95% CI=0.62, 0.80) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP below 141 mmHg, and by 26% (RR=0.74, 95% CI=0.66,0.83) for every 5 mmHg increase in DBP below 76 mmHg. For those not having the APOE ε4 allele (Table 2), the association did not show a U-shaped especially for DBP, for which it was linear with slightly lower risk of AD dementia at higher DBP (not significant quadratic term, p=0.58). For people with higher SBP and without the APOE ε4 allele, the RR increased by 13% (RR=1.13, 95% CI= 1.05, 1.21) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP above 143 mmHg, which was significantly lower than the relative risk for those with the APOE ε4 allele (95% CI of log RR difference= 0.13, 0.35; p<0.001). For those with lower SBPs and no APOEε4 allele, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 12% (RR=0.88, 95% CI=0.80, 0.96) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP below 143 mmHg, which was significantly different from those with the APOEε4 allele (95% CI of log RR difference= 0.11, 0.34; p<0.001). For DBP, a zone of threshold risk of AD dementia could not be calculated, since the association appeared to be roughly linear (not significant quadratic term, p=0.67).

Figure 3.

Log Hazard Function for the Association of Systolic and Diastolic BP with the Clinical Diagnosis of Incident AD dementia by BP Medication Use and the APOE ε4 Allele

Table 2.

Relative Risk (RR) of Clinical Diagnosis of Incident AD dementia for Every 10 mm Hg Increase in Systolic BP and 5 mm Hg Increase in Diastolic BP Above and Below the BP Threshold

| RR (95% CI) No BP Meds |

RR (95% CI) BP Meds |

RR (95% CI) No ε4 Allele |

RR (95% CI) Any ε4 Allele |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/AD | 912/191 | 1225/246 | 1330/245 | 608/160 |

|

| ||||

| Systolic BP | ||||

| Linear Risk | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.06) | 1.05 (0.98, 1.13) |

| SBP Threshold | 150 (148, 153) | 120 (110, 130) | 143 (140, 146) | 141 (138, 144) |

| 10 mm Hg below | 0.78 (0.72, 0.85) | 0.80 (0.58, 1.09) | 0.88 (0.80, 0.96) | 0.70 (0.62, 0.80) |

| 10 mm Hg above | 1.30 (1.17, 1.44) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.15) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.21) | 1.43 (1.29, 1.59) |

|

| ||||

| Diastolic BP | ||||

| Linear Risk | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) |

| DBP Threshold | 84 (80, 88) | 76 (74, 78) | – | 76 (74, 78) |

| 5 mm Hg below | 0.90 (0.84, 0.96) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.01) | – | 0.74 (0.66, 0.83) |

| 5 mm Hg above | 1.03 (0.84, 1.26) | 1.18 (1.10, 1.27) | – | 1.32 (1.20, 1.44) |

|

| ||||

| No ε4 Allele | Any ε4 Allele | |||

| No BP Meds | BP Meds | No BP Meds | BP Meds | |

|

| ||||

| N/AD | 585/105 | 745/140 | 245/70 | 363/90 |

|

| ||||

| Systolic BP | ||||

| Linear Risk | 0.89 (0.82, 0.97) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16)a | 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) |

| SBP Threshold | 153 (150, 156) | - | 139 (138, 140) | 141 (138, 144) |

| 10 mm Hg below | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86) | - | 0.56 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) |

| 10 mm Hg above | 1.29 (1.08, 1.54) | - | 2.00 (1.70, 2.31) | 1.17 (1.02, 1.35) |

|

| ||||

| Diastolic BP | ||||

| Linear Risk | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99)a | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16)a | 1.00 (0.81, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.28) |

| DBP Threshold | - | - | 76 (75, 77) | 76 (74, 78) |

| 5 mm Hg below | - | - | 0.60 (0.51, 0.72) | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) |

| 5 mm Hg above | - | - | 1.57 (1.33, 1.86) | 1.20 (1.07, 1.34) |

No observable change in pattern of log hazard function suggests the use of linear risk estimates

NOTE: Estimates adjusted for age, education, race, sex, heart disease, and diabetes. The presence of APOE ε4 allele adjusted for medication use, and medication use adjusted for APOE ε4 allele estimates

Modification by Use of Antihypertensive Medication

Comparing users of antihypertensive medication to non-users, the U-shaped association appeared most prominent for SBP among non-users of antihypertensive medication (Figure 3). For both SBP and DBP among users and for DBP among medication users, lower BPs were associated with modestly elevated risk of incident AD dementia, and higher BPs with greater elevation of risk. For medication users, the risk of incident AD dementia increased by 9% (RR= 1.09, 95% CI= 1.04, 1.15) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP above 120 mmHg, and by 18% (RR= 1.30, 95% CI= 1.17, 1.44) for every 5 mmHg increase in DBP above 76 mmHg. Below the threshold range, the RR of incident AD dementia was not significantly associated with SBP or DBP. Among medication non-users (Table 2), the risk of incident AD dementia increased by 30% (RR=1.30, 95% CI = 1.17, 1.44) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP above 150 mmHg, which was significantly higher than those taking BP medications (95% CI of log RR difference= 0.08, 0.27; p<0.001). For DBP among non-users, however, the association with risk of incident AD dementia was roughly linear with higher risk at lower DBPs; a zone of threshold risk of incident AD dementia was elevated on lower ends and flat on higher ends, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 10% (RR=0.90, 95%CI = 0.84, 0.96) for every 5 mmHg increase in DBP below 84 mmHg, and no observable elevated risk above the threshold. Participants taking BP medications had similar risk of incident AD dementia below the DBP threshold (95% CI of log RR difference= −0.13, 0.18; p=0.75) and above the DBP threshold (95% CI of log RR difference= −0.04, 0.31; p=0.128) compared to those not taking BP medications.

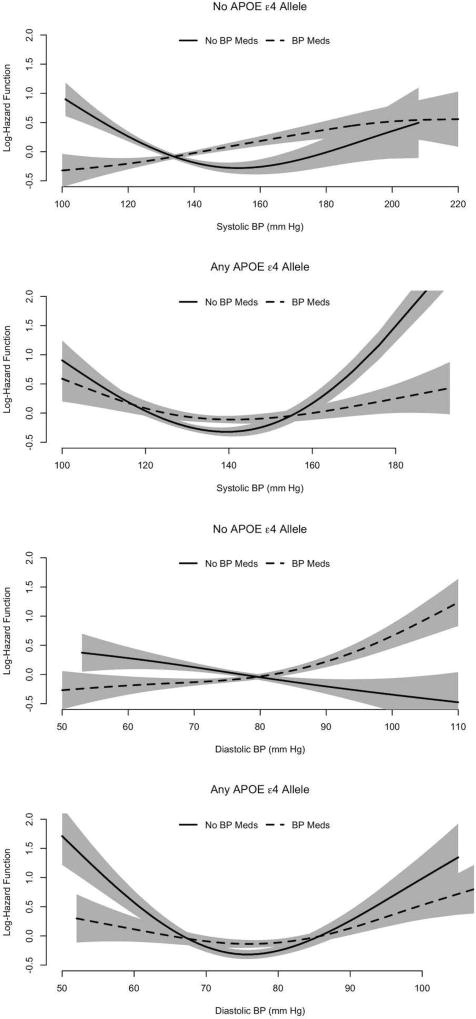

Interaction of Use of Antihypertensive Medication and Presence of the APOEε4 allele

In analyses considering use of antihypertensive medication and presence of the APOEε4 allele jointly, the risk of AD dementia was most substantially elevated among those having the APOE ε4 allele and not receiving any anti-hypertensive medication at higher BP levels. The SBP-AD dementia association was markedly U-shaped in this subgroup (Figure 4). Above the threshold (Table 2), the risk of incident AD dementia increased by 2-fold for every 10 mmHg increase in systolic BP over 139 mmHg (RR= 2.00, 95% CI = 1.70, 2.31). Below the threshold, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 44% (RR=0.56, 95% CI=0.46, 0.68) for every 10 mmHg increase in systolic BP below 139 mmHg. For DBP, the U-shape of the association was asymmetric with markedly higher risk of incident at higher DBP levels (Figure 4). Above 76 mmHg DBP, the risk of incident AD dementia was strongly elevated (Table 2): the risk of incident AD increased by 57% (RR=1.57, 95% CI = 1.33, 1.86) for every 10n mmHg increase in DBP. Below the threshold, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 40% (RR=0.60, 95% CI=0.51, 0.72) for every 5 mmHg increase in DBP. In the subgroup having the APOE ε4 allele and receiving anti-hypertensive medication, the SBP-AD dementia association was modestly U-shaped (Figure 4). Above 141 mmHg SBP (Table 2), the risk of increased AD dementia increased by 17% (RR=1.17, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.35) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP, which was significantly lower than the increase in risk for those with the APOEε4 allele above the threshold (95% CI of log RR difference= −0.69, −0.38; p<0.001). Below the threshold, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 19% (RR= 0.81, 95% CI = 0.67, 0.97) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP, and significantly different from the risk below the threshold among those with the the APOEε4 allele (95% CI of log RR difference= 0.20, 0.53; p<0.001). A similar U-shaped association was observed for diastolic BP.

Figure 4.

Log Hazard Function for the Association of Systolic BP with Clinical Diagnosis of Incident AD dementia in Combinations of BP Medication Use and the APOE ε4 Allele

Among those not having the APOE ε4 allele and not receiving anti-hypertensive medication, the SBP-AD dementia association was moderately U-shaped (Figure 4). Above 153 mmHg SBP, the risk of incident AD dementia increased by 29% (RR= 1.29, 95% CI = 1.08, 1.54) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP. Below the threshold, the risk of incident AD dementia decreased by 23% (RR=0.77, 95% CI=0.69, 0.86) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP. In the subgroup not having the APOE ε4 allele and receiving anti-hypertensive medication, the form of the SBP-AD dementia association differed from that seen for the three other subgroups, with little or no U-shape (Figure 4), and the highest risk at the highest SBPs and an optimal SBP region could not be calculated. For DBP, among those not having the APOE ε4 allele and not receiving anti-hypertensive medication, the association with risk of incident AD dementia was roughly linear with higher risk at lower DBP levels, and an optimal DBP region could not be calculated. Among those not having the APOE ε4 allele and receiving anti-hypertensive medication, the form of the association was curvilinear with a linear increase in the risk of incident AD dementia by 9% (RR=1.09, 95% CI= 1.02, 1.16) for every 5 mmHg increase in DBP, with no clear indication of the presence of a threshold DBP (not significant quadratic term, p=0.73). Among participants with no APOEε4 allele, significant difference in relative risk was found for those taking BP medications compared to those not taking BP medications (95% CI of log RR difference= 0.06, 0.27; p=0.004).

Sensitivity Analysis

The inclusion of health and lifestyle measures did not change the BP thresholds, but most notably, the risk of incident AD dementia among those not taking BP medications and without the APOE ε4 allele from 29% (RR=1.29, 95% CI= 1.08, 1.54) to 34% (RR=1.34, 95% CI= 1.13, 1.58) for every 10 mmHg increase in SBP over 153 mmHg. Health and lifestyle did not change the thresholds or risk estimates in other groups of the APOE ε4 allele and BP medications combinations. In an additional sensitivity analysis, we excluded individuals with the APOE ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, and ε2/ε4 from our analytic sample, and found that the BP thresholds and risk estimates did not show any notable differences. This may be due to the small number of individuals with the APOE ε2 alleles.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the association between BP and risk of developing AD dementia is U-shaped, with lowest risk of AD dementia near the center of the BP distribution. Lower BP was associated with modestly elevated risk of incident AD dementia and high BPs with higher risk. This association varied strongly with medication use and presence of the APOE ε4 allele. At higher BPs those having the APOE ε4 allele and not receiving anti-hypertensive medication were at greatly elevated risk of AD dementia.

Most epidemiologic studies of a BP-AD dementia association have used linear analytic techniques and focused on increased risk of AD dementia with higher BP. The large variation in results (reviewed in 2) may be partially attributable to the U-shaped association. Some studies, however, have suggested there may be elevated risk of AD dementia at both ends of the BP spectrum. Longitudinal results14 from the population-based Kungsholmen Study showed increased risk of dementia and AD dementia with SBP > 180 mmHg, but not with elevated DBP, and increased risk of dementia and AD dementia with diastolic BP ≤ 65 mmHg, but not with lower SBP. Cross-sectional results15,16 from the same study showed increased prevalence of among people with either lower SBP (≤ 140 mmHg vs. > 140 mmHg) or lower DBP (≤ 75 mmHg vs. > 75 mmHg). Results from the Bronx Aging Study17 showed increased risk of incident dementia with lower DBP. A combined analysis of data from the Rotterdam and Gothenburg population studies suggested reduced risk of dementia with higher SBP among those using antihypertensive medication.18 Pandav et al. reported an inverse cross-sectional association of cognitive impairment with higher SBP in the Indian arm of a cross-national study and a similar borderline association in the US arm.19

A few previous reports have also suggested that BP, the APOEε4 allele, and use of antihypertensive medication may interact: Peila et al. found higher risk of poor late-life cognitive function for people having the APOEε4 allele and higher midlife SBP.20 In contrast, Qiu et al. found higher risk of AD dementia for people having the APOEε4 allele and lower DBP who were also antihypertensive medication users.21 Studies22–26 have also suggested that the presence of the APOEε4 allele modifies the association of other vascular conditions with cognitive decline although findings have not been uniform.27,28

The mechanisms underlying the form of the observed associations are uncertain. Arguments have been made that U-shaped biological and pharmacological associations are a general phenomenon and an example of biological optimization.29 Among older people, some risk factor-disease associations seem either paradoxical in direction compared to those typically seen in middle age or demonstrate a U-shaped pattern.30 The U-shaped form of the BP-incident AD dementia association is generally consistent with this pattern, but insights as to the specific mechanisms involved are limited. Due to limited sample size and the type of modeling approach, formal comparisons of risk curves, notably the optimum thresholds and relative risk estimates was not performed, even when a confidence interval was estimated. Another limitation is that the variability around the hazard ratio curves were not estimated, since a bootstrap approach was used to estimate the variability around thresholds and variability in relative risks above and below the thresholds. A single class of medications with antihypertensive properties was considered, but the protective associations may vary by specific types of antihypertensive medications, which need to be further evaluated in future work.

Strengths of the study include its size, population-based biracial design, and long duration between BP measurements and clinical diagnosis of incident AD dementia. Limitations include the lack of plainly evident mechanisms underlying each of its four major findings: The U-shaped BP-AD dementia association, the modification of this association by presence of the APOEε4 allele and antihypertensive medication use, and the interaction of the APOEε4 and antihypertensive medication associations. Nonetheless, the observation of all four major findings with both SBP and DBP, consistency with some aspects of previous findings and ability to partially explain the great variation in results of previous studies of the BP-AD dementia association argue for careful consideration pending confirmation or refutation by future investigations. The strong risk of incident AD dementia seen with higher SBP and DBP among people having the APOE ε4 allele and not taking antihypertensive medication seems highly relevant to clinical care of this group, since use of antihypertensive agents in those with the APOE ε4 allele seems to have lower increases in relative risk of incident AD dementia.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by funds from the NIH grants – R01AG051635 (KBR), RF1AG057532 (KBR), and R01AG11101 (DAE).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Nothing to report.

Author Contributions: KBR and DAE contributed to concept and study design. KBR, DAE, LLB, RSW, JW, and EAM contributed to data acquisition and analysis, and drafting the text and figures.

References

- 1.Purnell C, Gao S, Callahan CM, Hendrie HC. Cardiovascular risk factors and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:1–10. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318187541c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Power MC, Weuve J, Gagne JJ, et al. The association between blood pressure and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2011;22:646–659. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31822708b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele, elevated midlife total cholesterol level, and high midlife systolic blood pressure are independent risk factors for late-life Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:149–155. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-3-200208060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-León J, Louis ED, et al. Risk of incident dementia in drug-untreated arterial hypertension: a population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:949–958. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden KM, Zandi PP, Lyketsos CG, et al. Vascular risk factors for incident Alzheimer disease and vascular: The Cache County study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:93–100. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213814.43047.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, Gureje O, et al. Risk factors for incident Alzheimer's disease in African Americans and Yoruba. Metab Brain Dis. 2006;21:235–240. doi: 10.1007/s11011-006-9017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay J, Laurin D, Verreault R, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:445–453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah RC, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, et al. Relation of blood pressure to risk of incident Alzheimer's disease and change in global cognitive function in older persons. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:30–36. doi: 10.1159/000089235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80:1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:185–189. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-AD dementia RDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Blood pressure studies in 14 communities; a two-stage screen for hypertension. JAMA. 1977;237:2385–2391. doi: 10.1001/jama.1977.03270490025018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eilers PHC, Marx BD. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and penalized likelihood. Statist Sci. 1996;11(2):89–121. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu C, von Strauss E, Fastbom J, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Low blood pressure and risk of dementia in the Kungsholmen project: a 6-year follow-up study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:223–228. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Z, Viitanen M, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B. Low blood pressure and dementia in elderly people: The Kungsholmen project. BMJ. 1996;312:805–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7034.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Z, Viitanen M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Low blood pressure and incidence of dementia in a very old sample: dependent on initial cognition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:723–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ. Low blood pressure and the risk of dementia in very old individuals. Neurology. 2003;6:1667–1672. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098934.18300.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruitenberg A, Skoog I, Ott A, Aevarsson O, Witteman JC, Lernfelt B, van Harskamp F, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Blood pressure and risk of dementia: results from the Rotterdam study and the Gothenburg H-70 Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12:33–39. doi: 10.1159/000051233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandav R, Dodge HH, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Blood pressure and cognitive impairment in India and the United States: a cross-national epidemiological study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1123–1128. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peila R, White LR, Petrovich H, et al. Joint effect of the APOE gene and midlife systolic blood pressure on late-life cognitive impairment: The Honolulu-Asia aging study. Stroke. 2001;32:2882–2889. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.100392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu C, Winblad B, Fastbom J, Fratiglioni L. Combined effects of APOE genotype, blood pressure, and antihypertensive drug use on incident AD dementia. Neurology. 2003;61:655–660. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.5.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalmijn S, Feskens EJ, Launer LJ, Kromhout D. Cerebrovascular disease, the apolipoprotein e4 allele, and cognitive decline in a community-based study of elderly men. Stroke. 1996;27:2230–2235. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.12.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofman A, Ott A, Breteler MM, et al. Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in the Rotterdam Study. Lancet. 1997;349:151–154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmelli D, Swan GE, Reed T, et al. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors, ApoE, and cognitive decline in elderly male twins. Neurology. 1998;50:1580–1585. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haan MN, Shemanski L, Jagust WJ, et al. The role of APOE epsilon4 in modulating effects of other risk factors for cognitive decline in elderly persons. JAMA. 1999;282:40–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carmelli D, DeCarli C, Swan GE, et al. The joint effect of apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and MRI findings on lower-extremity function and decline in cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M103–109. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knopman DS, Mosley TH, Catellier DJ, et al. Fourteen-year longitudinal study of vascular risk factors, APOE genotype, and cognition: the ARIC MRI Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debette S, Seshadri S, Beiser A, et al. Midlife vascular risk factor exposure accelerates structural brain aging and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2011;77:461–468. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227b227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. U-shaped dose-responses in biology, toxicology, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:15–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdelhafiz AH, Loo BE, Hensey N, et al. The U-shaped relationship of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and adverse outcomes in later life. Aging Dis. 2012;3:454–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]