Friendships are considered developmental necessities (Ladd, 1990; Sullivan 1953). In childhood, friends provide companionship and a critical context for learning social skills, such as cooperation and conflict resolution (Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). By early adolescence, at a time of increased independence from parents, close friends are presumed to meet additional social needs, such as validation, support, and intimacy (Sullivan, 1953). As such, friends provide adolescents with a sense of security and reassurance, protecting against adjustment problems and contributing to the development of self-worth. For example, even having just one friend attenuates the emotional and physiological consequences of negative social experiences (Adams, Santo & Bukowski, 2011; Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro & Bukowski, 1999). Those lacking a friendship (i.e., a close relationship with a same-aged peer) are, in turn, at risk for lower self-worth and increased depression (Wentzel, Barry & Caldwell, 2004).

In spite of evidence demonstrating the socioemotional toll of lack of friends during adolescence, the underlying mechanisms between friendlessness and internalizing difficulties (e.g., depression and low self-esteem) have not received much empirical attention. Guided by social-cognitive models in which interpersonal interactions, or lack thereof, are presumed to shape perceptions of the social world (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1994), the current study examined how lack of friends might be related to perceptions of the school social environment. While friendships promote trust and positive social perceptions (Sullivan, 1953), friendless students in elementary school are more likely to perceive themselves as victimized by peers (Hodges et al., 1999). Not surprisingly, peer exclusion and isolation are in turn related to feeling unsafe in school among adolescents (Goldstein, Young & Boyd, 2008). Moreover, the distress associated with friendlessness is partially accounted for by negative beliefs about peers (e.g., peers are hurtful and untrustworthy; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003). Such negative social perceptions (i.e., victimization, school unsafety, negative views of schoolmates) are consistent with Cacioppo and Hawkley’s social-cognitive model of loneliness wherein perceived isolation sets off implicit hypervigilance for social threat in the environment (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). Accordingly, we presume friendless youth are likely to construe their school social environment as threatening by viewing themselves as victimized by schoolmates, feeling unsafe in school, and estimating more of their peers engaging in hostile behaviors. By relying on such a multifaceted construct, we expect that perceived social threat may then help account for the internalizing difficulties associated with friendlessness (Kuperminc, Leadbeater & Blatt, 2001). Drawing from the adult literature, perceived social threat is also known to encourage behavioral withdrawal and thus stimulate a “negative feedback loop” wherein isolation is reinforced (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Thus, the way adolescents view their school social environment may also provide insight into why youth remain friendless over time (Bowker, Rubin, Burgess, Booth-LaForce & Rose-Krasnor, 2006).

Perceptions of social threat are especially relevant in early adolescence when youth transition from their elementary school to a new and much larger middle school environment (grades 6 to 8), which often disrupts past friendship networks (Eccles et al., 1993). Thus, establishing friendships is critical following the transition to middle school (Akos & Galassi, 2004; Lessard & Juvonen, 2017) and the lack of a close peer relationship might be particularly hurtful at this time of heightened social sensitivity (Blakemore & Mills, 2014). If the social needs provided by friendship are unfulfilled, lacking a friend during early adolescence may contribute to sense of insecurity or perceived social threat, increasing internalizing difficulties at this developmental phase and beyond (Bagwell, Newcomb & Bukowski, 1998).

The Current Study

The primary goal of the current study was to investigate whether perceptions of social threat help account for the development of internalizing difficulties among friendless adolescents across the three years of middle school (ages 11–13). Additionally, we tested whether perceived social threat predicts subsequent friendlessness. Social threat was operationalized as a broad multifaceted construct capturing heightened accessibility of negative social information including peer victimization experiences, perceiving school as unsafe, and estimating a higher proportion of schoolmates engaging in hostile behaviors. Friendlessness was assessed by relying on received peer nominations. Friendless youth were compared to those with at least one friend in the spring of their first year of middle school (i.e., 6th grade), when students had already had several months to get to know one another. It was hypothesized that absence of friends at school reflects a lack of friendship provisions (e.g., companionship, support), increasing the likelihood that youth view their school social environment as threatening. Specifically, we hypothesized that friendlessness by the end of 6th grade predicts greater sense of threat by 7th grade, which in turn, is associated with increased internalizing difficulties (i.e., depressive symptoms, social anxiety and low self-esteem) by 8th grade. Both perceived social threat and internalizing difficulties were represented as latent constructs in the model assessing the indirect effect of friendlessness through perceived social threat. As a secondary aim, we also examined whether 7th grade perceptions of social threat predict lack of friends at the end of middle school.

The present study contributes to the existing research in several ways. First, by focusing on a social-cognitive construct of perceived social threat, we underscore the role of the school context. This approach complements previous findings highlighting the social deficiencies (e.g., lack of social skills) of friendless youth (Glick & Rose, 2011). Second, we believe that perceptions of one’s social environment are important inasmuch as they are likely to help account for subsequent internalizing difficulties as well as future social isolation (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Third, we examined these questions following a critical school transition across three years of middle school. Finally, because we relied on an ethnically diverse public school sample, we presume that the findings generalize across a range of demographic groups.

Method

The current study relies on data from a large, longitudinal study of adolescents recruited from 26 public middle schools in California that varied systematically in ethnic composition (N=5,991; 52% female). Based on self-reported ethnicity in the fall of 6th grade, the sample was 32% Latino/a, 20% Caucasian/White, 13% East/Southeast Asian, 12% African-American/Black and 23% from other ethnic groups. The proportion of students eligible for free/reduced lunch price (a proxy for school SES) ranged from 18% to 86% (M=47.6, SD=18.3) across the 26 schools. Eighty-five and 78% of the total sample were retained in 7th grade and 8th grade respectively.

Procedure

The study was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board and school districts. All eligible 6th grade students and families received informed consent and informational letters. Parental consent rates averaged 81% across the schools. Data collection was conducted in schools, and students received $5 in the 6th grade and $10 in 7th and 8th grade for completion of the surveys.

Measures

Friendlessness.

Presence versus absence of friends was determined using an unlimited peer nomination procedure where students listed the names of their good friends in their grade at school. Rather than relying on lack of reciprocal friendships that tend to overestimate friendlessness (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2013) or friendship nominations given that are likely to include desired friendships (Echols & Graham, 2016), we relied on received friendship nominations (Schacter & Juvonen, 2017). Friendlessness was coded as 0 (one or more friendship nominations received) or 1 (no nominations received). While we relied on friendlessness in the spring of 6th grade when testing the mediation hypothesis, we used 7th and 8th grade friendship data when predicting friendlessness by the end of middle school.

Perceived Social Threat.

Three indicators were used to assess perceived social threat at 7th grade: peer victimization, school safety, and peer misconduct. Peer victimization (α=.78) was assessed with four items adapted from a measure developed by Neary and Joseph (1994). Designed to reduce social desirability effects, participants first chose one of two options for each item (e.g., “Some kids are often picked on by other kids” but “Other kids are not picked on by other kids”). Thereafter they rated if it was “really true” or “sort of true” for them (resulting in a 4-point scale). School safety (α=.80) was measured using a subscale taken from the Effective School Battery (Gottfredson, 1984). Six items (e.g., “Are you afraid that someone will hurt or bother you at school?”) were rated on a 5-point scale (1=always to 5=never). Peer misconduct (α=.84) was assessed by asking participants to estimate the number of grademates engaging in hostile and potentially threatening social behaviors (e.g., “get in fights” or “make fun of others”) on a 5-point scale (1=hardly any to 5=almost all the students).

Internalizing Difficulties.

Three indicators were used to assess internalizing difficulties at 6th and 8th grade: depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and self-esteem. Depressive symptoms (αgr6=.80; αgr8=.85) were measured using 7-items assessed consistently at 6th and 8th grade (e.g., “I felt sad”) that were adapted from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). Items were rated on frequency over the past week (1=less than 1 day to 4=5–7 days). Social anxiety (αgr6=.82; αgr8=.81) was assessed using six items (e.g., “I worry about what others say about me”), rated on a 5-point scale (1=not at all to 5=all the time). This measure was adapted from the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). Self-esteem (αgr6=.75; αgr8=.88) was measured using four items of the Self-Perception Profile scale (Harter, 1982). For each item, participants chose one of two options (e.g., “Some kids are often unhappy with themselves” but “Other kids are pretty pleased with themselves”) and then rated the applicability of each (1=really true for me to 4=sort of true for me).

Covariates.

The current analyses controlled for self-reported gender and ethnicity. Baseline internalizing difficulties were controlled at the fall of 6th grade when data on all three internalizing indicators was available. We also took into account ethnic ingroup size (i.e., proportion of same-ethnic peers) because lack of ethnically similar others may contribute to the friendlessness of those in the numerical minority at their school. Finally, parent education (1=elementary/junior high school to 6=graduate degree) was used as a proxy for student socioeconomic status (SES) given that children with low SES are at higher risk of mental health problems (Reiss, 2013).

Data Analytic Strategy

Latent variable structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the relations among the study constructs using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation methods were used for missing data (Enders, 2010). The Cluster function was used to account for students nested within 26 middle schools. Following recommended procedures, we used bias-corrected bootstrapping procedures (10,000 bootstraps) to estimate indirect effect of friendlessness on internalizing difficulties through perceived social threat and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). A logit model was used to test our secondary question of whether perceived social threat predicts friendlessness (a dichotomous outcome) by the end of middle school.

Results

Twelve percent (n=729) of 6th grade students did not receive any friendship nominations and were considered friendless. Boys (16%) were more likely to be friendless than girls (9%), χ2(1)=64.42, p<.01. In addition, there were significant ethnic differences in friendlessness, χ2(4)=12.39, p=.02: African-American (14%) and Latino (13%) students were more likely to be friendless than White students (9%), while Asian students (11%) and those from other ethnic groups (11%) did not differ. In addition to the means and standard deviations, the intercorrelations among the modeled variables depicted in Table 1 reveal that friendlessness is indeed associated the indicators of perceived social threat, but weakly and inconsistently related to the indicators of internalizing difficulties at Grade 6 and 8.1

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations between modeled variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Friendlessnessgr6 | ---1 | |||||||||||

| 2. Ethnic Ingroup Sizegr6 | −.01 | ---1 | ||||||||||

| 3. SESgr6 | −.05*** | −.30*** | ---1 | |||||||||

| 4. Victimizationgr7 | −.07*** | −.09*** | −.17*** | ---1 | ||||||||

| 5. Safetygr7 | −.06*** | −.09*** | −.05*** | −.34*** | ---1 | |||||||

| 6. Peer Misconductgr7 | −.04** | −.05*** | −.09*** | −.36*** | −.30*** | ---1 | ||||||

| 7. Depressiongr6 | −.02 | −.00 | −.05*** | −.22*** | −.26*** | −.22*** | ---1 | |||||

| 8. Social Anxietygr6 | −.04** | −.04** | −.05** | −.19*** | −.28*** | −.11*** | −.42*** | ---1 | ||||

| 9. Self-esteemgr6 | −.06*** | −.07*** | −.10*** | −.27*** | −.20*** | −.19*** | −.37*** | −.37*** | ---1 | |||

| 10. Depressiongr8 | −.04 | −.05* | −.00 | −.18*** | −.20*** | −.16*** | −.35*** | −.22*** | −.19*** | ---1 | ||

| 11. Social Anxietygr8 | −.03 | −.01 | −.06** | −.14*** | −.26*** | −.09*** | −.24*** | −.38*** | −.21*** | −.42*** | ---1 | |

| 12. Self-esteemgr8 | −.03* | −.05** | −.01 | −.21*** | −.19*** | −.14*** | −.26*** | −.24*** | −.29*** | −.51*** | −.45*** | ---1 |

| Mean | −.12 | −.32 | 4.00 | 1.98 | 4.27 | 2.33 | 1.58 | 2.08 | 3.32 | 1.70 | 2.09 | 3.21 |

| SD | −.33 | −.16 | 1.53 | .78 | .64 | .77 | .57 | .78 | .71 | .65 | .76 | .82 |

Note. Gender reference group=boys. Ethnicity reference group=Latino.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Mediation Analyses

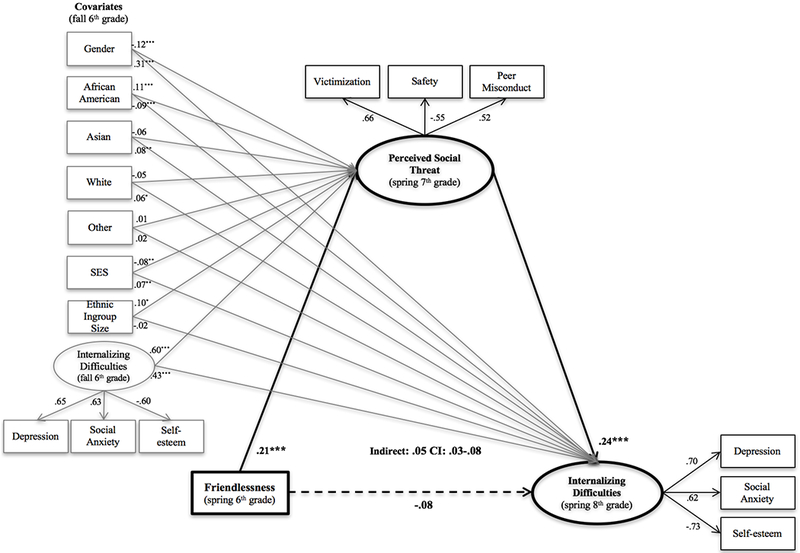

When testing the mediation model, multiple fit indices suggested a good measurement model [χ2(80)=923.06, p<.01; SRMR=0.03; RMSEA=0.04, RMSEA CI=.040-.044], with all factor loadings above .50 (see Figure 1). As seen in Figure 1, after accounting for the covariates (i.e., baseline internalizing difficulties, gender, ethnicity, SES, ethnic ingroup size), not having a friend was associated with higher perceived social threat (β=.21, p<.01). Additionally, higher perceived social threat was related to increased internalizing difficulties (β=.24, p<.01). Despite the non-significant total effect of friendlessness at 6th grade on internalizing difficulties at 8th grade, the indirect effect was examined in light of our theoretical predictions (Rucker, Preacher, Tormala & Petty, 2011). As shown in Figure 1, there was a significant indirect path from friendlessness to internalizing difficulties (standardized indirect effect=.05, C.I.: .03-.08). That is, not having a friend at 6th grade predicted higher perceived social threat at 7th grade, which in turn predicted increased internalizing difficulties at 8th grade.2

Figure 1.

Standardized factor loadings and coefficients for model of friendlessness and perceived social threat on adolescents’ internalizing difficulties.

Note. Gender reference group=boys. Ethnicity reference group=Latino. *p<.05 **p<.01 ***p<.001

Does Perceived Social Threat Predict Friendlessness?

Secondarily we explored how perceived social threat predicts future social isolation. A logit model predicting friendlessness (0=one or more friends, 1=friendless) at 8th grade was used to examine how perceived social threat might contribute to friendlessness at the end of middle school. Friendlessness at 8th grade was regressed on perceived social threat at 7th grade. The results suggested that each one unit increase in perceived social threat at 7th grade predicted a 16% increase in the odds of being friendless one year later (OR= 1.55, p<.01), over and above gender, ethnicity, SES, ethnic ingroup size and earlier (i.e., 7th grade) friendlessness.

Taken together, the results suggest that not having a friend during the first year of middle school puts youth at risk for perceiving their school environment as more threatening, which, in turn increases internalizing difficulties by 8th grade. Moreover, perceptions of social threat increase the likelihood of future friendlessness.

Discussion

Despite theoretical assertions about the importance of friendships in the social and emotional development of adolescents (Sullivan, 1953), surprisingly few studies examine the experience of adolescent friendlessness (see Wentzel et al., 2004 for exception). Even less is known about the psychological mechanisms that might help account for the emotional difficulties of youth who lack friends at school. By relying on prospective longitudinal data following the transition to middle school, we show how lacking friends by the end of 6th grade increases perceptions of social threat, which in turn, contributes to the development of depressive symptoms, social anxiety and low self-esteem by 8th grade. Hence, our findings offer a social-cognitive account on the liabilities of not having a chum or a buddy in early adolescence.

Our findings suggest that friendlessness during the first year in middle school does not directly predict internalizing difficulties by the end of middle school. Rather, youth without friends came to see their social environment as more hostile and unsafe by the second year of middle school (7th grade), which in turn, predicted increased internalizing difficulties by 8th grade. With fewer opportunities to engage in supportive, validating and intimate relationships with their peers, friendless youth may be more wary of their schoolmates. For example, lack of companionship (e.g., someone to sit with at lunch) and instrumental aid (e.g., someone to stick up for them) are likely to contribute to perceptions of social threat. In contrast, those with close friendships may generalize their experiences by developing feelings of trust and safety towards the larger school environment (cf. Berndt, 2004).

Our findings are generally consistent with Cacioppo and Hawkley’s (2009) social-cognitive model of loneliness. Although we did not investigate hypervigiliance for social threat, our results suggest that perceived social threat contributes to future isolation (i.e., friendlessness). Negative social perceptions and expectations may undermine adolescents’ motivation to engage with the social environment, paving the way for continued objective isolation (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). However, similar to subtypes of socially withdrawn children (Harrist, Zaia, Bates, Dodge & Pettit, 1997), it is important to recognize that some friendless youth may prefer to be alone. If friendlessness does not raise threat perceptions, it is unlikely to also contribute to internalizing difficulties.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our measures of social threat and internalizing difficulties relied on self-reports. In future studies, it will be important to also include objective measures of the school environment (e.g., school-level aggression, discipline problems). Second, by relying on friendship nominations from participants, we were unable to differentiate friendless youth who have no friends at all from those who may have friends in other grades or outside of school. Third, we did not take into account the duration of friendlessness. In light of research suggesting that chronic social isolation is particularly harmful to psychological health (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006), future studies should examine whether a history of friendlessness helps account for an accumulation of adjustment problems. It is unclear how long you need to be friendless before threat perceptions come online and whether external factors (e.g., group-level acceptance, school prosocial norms) may influence this association.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature on negative peer experiences by demonstrating that friendlessness is related to negative social perceptions and internalizing difficulties. Although some interventions have been developed to help friendless youth by assigning them a “buddy” at school, there has been limited empirical support for the effectiveness of such befriending interventions (Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011). Instead, interventions that focus on fostering more positive social norms (e.g., antibullying programs designed to change school culture) may serve friendless youth better inasmuch as they reduce reports of peer victimization and increase overall school safety. Even if youth are not in the position to form or maintain a friendship, they may feel less threatened if they witness kindness and caring interactions among schoolmates.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Sandra Graham (PI of the Project) and the members of the UCLA Middle School Diversity team for their contributions to collection of the data, and all school personnel and participants for their cooperation. We also appreciate the feedback by Peter Bentler, Hannah Schacter and Danielle Smith on an earlier version of this paper.

Funding This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1R01HD059882–01A2) and the National Science Foundation (No. 0921306).

Footnotes

To evaluate factorial validity for perceived social threat and internalizing difficulties, a two-construct Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted which suggested good model fit [χ2(15)=3562.06, p<.01; SRMR=0.03; RMSEA=0.04, RMSEA CI=.035-.051].

Supplemental analyses revealed evidence for a similar, albeit weaker, mediation process when testing the model separately for each indicator of perceived social threat (providing additional support for the validity of the latent construct).

References

- Adams RE, Santo JB, & Bukowski WM (2011). The presence of a best friend buffers the effects of negative experiences. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1786–1791. doi: 10.1037/a0025401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akos P, & Galassi JP (2004). Middle and high school transitions as viewed by students, parents, and teachers. Professional School Counseling, 7, 212–221. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42732584 [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Newcomb AF, & Bukowski WM (1998). Preadolescent friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. Child Development, 69, 140–153. doi: 10.2307/1132076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, & Schmidt ME (2013). Friendships in Childhood and Adolescence. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, & Schmidt ME (2011). The friendship quality of overtly and relationally victimized children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57, 158–185. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2011.0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ (2004). Children’s friendships: Shifts over a half-century in perspectives on their development and their effects. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50, 206–223. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2004.0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ & Mills K (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton MJ, Trueman M, Chau C, Whitehand C, & Amatya K (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal links between friendship and peer victimization: implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 461–466. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker JCW, Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Booth-LaForce C, & Rose-Krasnor L (2006). Behavioral characteristics associated with stable and fluid best friendship patterns in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 671–693. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23096029 [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, & Hawkley LC (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13, 447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Wigfield A, Midgley C, Reuman D, Iver DM, & Feldaufer H (1993). Negative effects of traditional middle schools on students’ motivation. The Elementary School Journal, 93, 553–574. doi: 10.1086/461740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Echols L, & Graham S (2016). For better or worse: Friendship choices and peer victimization among ethnically diverse youth in the first year of middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1862–1876. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0516-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied Missing Data Analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glick GC, & Rose AJ (2011). Prospective associations between friendship adjustment and social strategies: Friendship as a context for building social skills. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1117–1132. doi: 10.1037/a0023277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE, Young A, & Boyd C (2008). Relational aggression at school: Associations with school safety and social climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 641–654. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9192-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson GD (1986). Using the Effective School Battery in School Improvement and Effective Schools Programs. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/63245700/138AF469B2958EB7CFD/1?accountid=14512 [Google Scholar]

- Harrist AW, Zaia AF, Bates JE, Dodge KA, & Pettit GS (1997). Subtypes of social withdrawal in early childhood: Sociometric status and social-cognitive differences across four years. Child Development, 68, 278–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich LM, & Gullone E (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 695–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EV, Boivin M, Vitaro F, & Bukowski WM (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35, 94–101. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperminc GP, Leadbeater BJ, & Blatt SJ (2001). School social climate and individual differences in vulnerability to psychopathology among middle school students. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 141–159. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00059-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, & Lopez N (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 83–95. doi: 10.1023/A:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development, 61, 1081–1100. doi: 10.2307/1130877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard LM & Juvonen J (2017). Losing and gaining friends: Does friendship instability compromise academic functioning in middle school?. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus user’s guide. (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neary A, & Joseph S (1994). Peer victimization and its relationship to self-concept and depression among schoolgirls. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, & Bagwell CL (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 306–347. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss F (2013). Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 90, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, & Petty RE (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 359–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter HL & Juvonen J (2017). The power of context: Can prosocial middle schools alleviate the distress of youth with co-occurring social difficulties? Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR, Barry CM, & Caldwell KA (2004). Friendships in middle school: Influences on motivation and school adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 195–203. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]