Abstract

Infective endocarditis is a potentially lethal infection, which predominantly affects the atrioventricular valves. Rapid identification and management is critical to reduce morbidity and mortality in this patient population. Herein, we present a case of a 24-year-old man with Leuconostoc species infective endocarditis of the aortic valve. Disease course was complicated by several septic emboli to the brain, central retinal artery, and spleen. This case serves to remind clinicians that Leuconostoc species, which are typically not pathogenic to human species, can cause infective endocarditis in individuals with a history of intravenous drug use.

<Learning objective: It is crucial that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion in high-risk patients for infective endocarditis with Leuconostoc species, especially in the setting of positive blood cultures with group viridans streptococcus resistant to penicillin. Although cases of penicillin resistant group viridans streptococci have been reported, it is not common and merits further review. Leuconostoc is a Gram-positive ovoid cocci that is intrinsically vancomycin-resistant and is typically non-pathogenic to the human species.>

Keywords: Leuconostoc, Infective endocarditis, Septic emboli

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is most commonly caused by the hematogenous spread of various microorganisms that target the endocardium of heart chambers and valves, with staphylococci and streptococci accounting for the majority of cases. Due to the multitude of bacterial and even fungal pathogens, treatment options should be targeted specifically to eradicate microorganisms that are isolated in blood cultures. If empiric therapy is warranted, first-line treatment usually targets methicillin susceptible and resistant staphylococci, streptococci, and enterococci. Although, there is an important caveat clinicians must consider when using vancomycin antibiotic therapy. When dealing with IE caused by Leuconostoc, vancomycin is not a suitable option for treatment [1]. Leuconostoc is a genus of Gram positive, catalase and oxidase negative, cocci placed within the family of leuconostocaceae [1], [2]. It was previously believed that this bacterial species was non-pathologic in nature until recently published reports revealed the infectious potential of the Leuconostocspecies in many patient populations [2]. Although there have been previously reported sensitivity panels for this organism, it has a high level of intrinsic vancomycin resistance and therefore merits a higher index of suspicion when discussing endocarditis [1]. The case presented here serves to remind clinicians of the devastating potential of untreated infective endocarditis and to raise awareness for the possibility of infection with the typically non-pathogenic Leuconostoc species.

Case report

Presentation

The patient was a 24-year-old male tobacco smoker with a past medical history of intravenous drug use (IVDU), bicuspid aortic valve, and untreated hepatitis C who presented with two weeks duration of worsening bilateral temporal headaches and intermittent fevers. He described the headaches as bilateral, temporal, throbbing, pressure-like, non-radiating, and intermittent. The patient had been taking high-dose ibuprofen for two weeks without any relief of symptoms. He also reported having intermittent vision loss precipitated by lateral movement of his head. Other associated symptoms included tinnitus in his right ear and photosensitivity in the right eye. The patient also had a persistent petechial rash in the lower extremities bilaterally. On presentation, the patient’s blood pressure was 99/64 mmHg, heart rate was 103/min, temperature was 36.7 °C, respiratory rate was 18/min, and oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Physical examination was remarkable for dilated pupils (diameter 7 mm), a grade IV/VI systolic ejection murmur radiating to the carotid artery bilaterally, Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and a bilateral non-blanching petechial rash below the knees bilaterally. Pertinent laboratory studies included: white blood cell count (WBC) 18,000/μl, C-reactive protein (CRP) 104 mg/dl, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 68 mm/h, creatinine (Cr) 4.6 mg/dl (baseline Cr 0.9 mg/dl), complement component 3 (C3) 56.6 mg/dl, complement component 4 (C4) 25.2 mg/dl, fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) 3.5%. The patient also had a troponin I elevation to 1.55 ng/ml without any electrocardiogram (ECG) changes or anginal symptoms.

Imaging studies

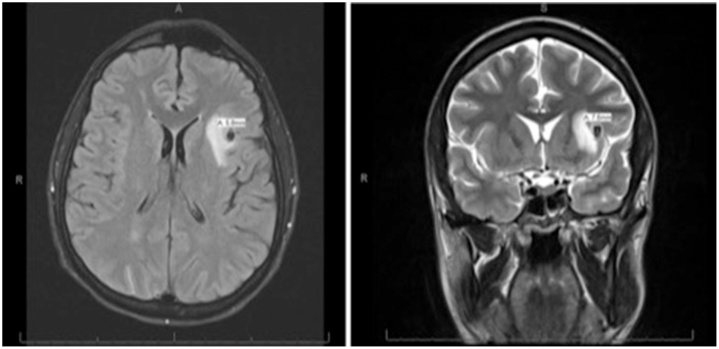

The initial chest X-ray (CXR) demonstrated mild cardiomegaly without any pulmonary or osseous abnormalities. Initial non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed a 2.5 cm region of hypo-attenuation in the left frontal lobe. Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (Fig. 1) showed a focal area of hypo-attenuation seen on T2, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) sequences within the subcortical left frontal lobe measuring 6 mm. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) (Fig. 2) demonstrated a bicuspid aortic valve with calcified leaflets and reduced cusp separation, severe aortic regurgitation, moderate aortic stenosis with a valve area of 1.22 cm2, and vegetations on both leaflets of the aortic valve. There was also grade 1 diastolic dysfunction and a moderate pericardial effusion. The left ventricular size was within normal limits and the left ventricular ejection fraction was 55–60%. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed a 2.6 cm aortic root with no definitive evidence of abscess and confirmed the TTE findings of aortic valve vegetations. Final measurements of the aortic valve vegetations were never determined due to the extent of vegetation involvement and fibrosis within native myocardial tissue. The largest vegetation was approximated to be at least 1.2 cm at its largest length. Neuroangiography (Fig. 3) revealed a 6.9 × 5.3 mm mycotic aneurysm of the left distal M2 branch of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) with subtle subarachnoid hemorrhage and left central retinal artery occlusion. CT without contrast of the abdomen was remarkable for splenomegaly and multiple areas of low density in the spleen, consistent with splenic infarction. Renal ultrasound showed increased echogenicity and edematous parenchyma. Non-contrast CT of the chest was remarkable for multifocal alveolar infiltrates throughout both upper and lower lobes and patchy consolidations in lower lobes.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast of the brain showing a focal area of hypo-attenuation seen on T2, fluid attenuated inversion recovery, and diffusion weighted imaging sequences within the subcortical left frontal lobe measuring 6 mm. The focus is hyper-intense on T1 non-contrast MRI.

Fig. 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography showing a bicuspid aortic valve with moderate valve stenosis and bacterial vegetation.

Fig. 3.

Diagnostic cerebral angiogram showing left distal middle cerebral artery M2 branch aneurysm measuring 6.89 × 5.29 mm in the Sylvian fissure (A, B, C). Repeat cerebral angiogram showing no residual aneurysm in the left middle cerebral artery territory with embolization coil seen in the Sylvian fissure (D).

Infectious disease consultation

Considering the results of imaging studies and clinical findings, a diagnosis of embolic phenomenon in the setting of left-sided endocarditis was established. The patient was started on vancomycin 1000 mg intravenous (IV) daily and ceftriaxone 1 g IV daily, which eventually was deescalated to ceftriaxone alone for viridans streptococcus group bacteremia on initial blood cultures. Aerobic and fungal cultures were negative. Interestingly, on blood culture sensitivity panel, the viridans streptococcus was not sensitive to penicillin. Considering the penicillin resistance, repeat cultures were sent to an outside laboratory for further analysis, eventually returning positive for Leuconostoc species. Antibiotic therapy was switched to ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily and daptomycin 600 mg IV daily. A six-week course of IV antibiotics after negative repeat blood cultures was planned as is typically performed for complicated endocarditis.

Ophthalmology consultation

On the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient developed acute onset left-sided blindness. Repeat MRI showed an acute punctate infarct in the left occipital and left parietal lobe and left central retinal artery occlusion in addition to the previously visualized focus of chronic hemorrhage within the left frontal lobe. Ophthalmology had been contacted for assistance in evaluating the patient’s acute blindness. Findings of disc edema were present bilaterally.

Nephrology consultation

Nephrology had been consulted to assist in the management of the patient’s acute kidney injury (AKI). Throughout the patient’s hospitalization, his AKI resolved with normal saline IV fluid hydration and by withholding any nephrotoxic agents. It is thought that the elevated creatinine and transient decrease in renal function was likely due to prolonged high-dose ibuprofen consumption. The possibility of endocarditis-associated glomerulonephritis was also discussed, but due to the patient’s rapid recovery in renal function a biopsy was not pursued.

Neurology and interventional neurology consultation

Neurology and interventional neurology were consulted for assistance in management of the mycotic aneurysm with subtle subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient was started on levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily for seizure prophylaxis. In the setting of optic disc edema with intracranial hemorrhage, blood pressure control was suggested. Approximately one week after presentation, surgical intervention for protection of the mycotic aneurysm was performed via coil embolization of the proximal feeding MCA branch, thus causing complete obliteration of anterograde aneurysm flow.

Cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery consultation

Cardiothoracic surgery and cardiology had been contacted for assisting in management of the aortic valve vegetations. The patient was taken for surgical intervention, which included replacement of the aortic root and valve with a CryoLife 23 mm × 6 cm homograft aortic valve and conduit (Kennesaw, GA, USA). Surgery was performed approximately one week after coil embolization. Upon entry, a large amount of straw-colored pericardial effusion was noted. There was extensive aortic root destruction with severe aortic insufficiency and a dilated left ventricle. Large vegetations were identified on the aortic valve leaflets. Vegetation size was difficult to assess, as inflammatory changes were so severe, the team was unable to differentiate between valve tissue and vegetation. There were also multiple abscesses at the left and right ventricular outflow tracts. The left main coronary artery was also extensively involved, which was notably inflamed and edematous. After debridement and aortic root with valve replacement, the patient was transferred back to the intensive care unit with four mediastinal chest tubes. Cardiologists also mentioned that the finding of pericardial effusion was likely a result of aortic root inflammation in the setting of root abscess. Surgically resected tissue cultures (bacterial, anaerobic, and fungal) were negative.

Discharge conditions

The patient was discharged approximately one month after presentation, to continue levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily for seizure prophylaxis and metoprolol 25 mg twice daily for blood pressure control. Arrangements were made for outpatient antibiotic infusion with ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily and daptomycin 600 mg IV daily for a total of six weeks after negative blood cultures were obtained.

Discussion

This case depicts the unfortunate story of an IVDU afflicted by a complicated course of infective endocarditis with an uncommon organism. What had initially been described as a nagging headache, quickly developed into what we now know to be Leuconostoc species bacteremia from seeded aortic valves with multi-organ septic emboli. In evaluating what may have led to this patient's eventual clinical course, it is imperative to note any predisposing factors. Notably, this patient had a history of IVDU and a bicuspid aortic valve, both of which had placed our patient at an elevated risk for infective endocarditis. This case is interesting in that the pathogenic bacterial species for IE are typically staphylococci and streptococci, not Leuconostoc species. In fact, it was previously thought that Leuconostoc species were not pathogenic in humans. Of clinical significance, this bacterial genus is notoriously known for its intrinsic vancomycin resistance, which quickly separates it from staphylococci [1]. Leuconostoc is a genus of Gram-positive, catalase and oxidase negative, chain forming ovoid cocci placed within the family of leuconostocaceae [1], [2], [3]. This bacterial species was thought to be non-pathologic until recently published reports have revealed the infectious potential of Leuconostoc species in immunocompromised and severely ill patients [4], [5]. IE with Leuconostoc species can be troubling considering they are hetero-fermentative and potentially “slime” (dextran and sucrose producing) forming.

In our case, suspicion for Leuconostoc arose when initial blood cultures returned as group viridans streptococci with resistance to penicillin. Although cases of penicillin-resistant streptococcus endocarditis have been reported in the literature [6], it is not common and prompted further culture analysis. We urge other clinicians to also have suspicion for possible Leuconostoc infection when finding penicillin-resistant streptococci. Unfortunately, the available laboratory was unable to differentiate between penicillin-resistant group viridans streptococci and Leuconostoc with certainty, which limited our ability to narrow antibiotic coverage. Although studies show complete elimination of most bacterial pathogens of endocarditis with two to four weeks of mono-therapy, we opted to treat our patient for six weeks following the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for treatment of penicillin-resistant bacteria in a high-riskpatient [7]. Additionally, the AHA advises that daptomycin alone is not effective against multidrug resistant IE and should be used in combination with other agents [7]. Upon further review of the available literature on Leuconostoc species infection, several studies listed daptomycin as an effective treatment for Leuconostoc-associated bacteremia [8]. Considering our patient had uncommon bacteria, aortic root abscess, and an aortic valve replacement, we pursued a full six-week course of IV antibiotic therapy. Although published reports do show effective therapy of penicillin-resistant group viridians streptococci (GVS) with combination therapy, typically ceftriaxone or penicillin with gentamycin [9], our team believed that initial blood cultures with resistant GVS was a laboratory error due to a lack of ability to test for Leuconostoc species and that only Leuconostoc species grew on send out cultures. Thus, we opted for empiric treatment with ceftriaxone for the possibility of GVS IE and daptomycin for Leuconostoc species bacteremia.

Surgical intervention must also be discussed as our patient had many risk factors and complications that altered his therapeutic course. The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend early surgical intervention for any patient with complicated infective endocarditis or evidence of persistent infection, heart block, abscess, or infection with a resistant organism [10]. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends urgent surgery for evidence of uncontrolled infection, which is defined as the presence of abscess, fistula, pseudoaneurysm, enlarging vegetation, persistent fevers, or positive blood cultures 7–10 days after appropriate antibiotic therapy [10]. Additionally, both the AHA and ACC recommend early surgery for recurrent emboli or persistent vegetation despite appropriate antibiotic therapy [10]. In accordance with the recommendations made by the AHA, ACC, and ESC, defining early surgery as occurring during the initial hospitalization and before completion of the full therapeutic antibiotic course, our patient underwent aortic valve and root replacement for complicated IE with a resistant organism with multiple embolic events and aortic root abscess approximately two weeks after initial presentation and initiation of antibiotics. The risks for perioperative neurological deterioration due to worsening intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral edema, hypotension, and neurological ischemia were discussed with the patient and family. A collaborative decision was made to continue with the proposed surgical intervention.

Again, we urge clinicians to consider Leuconostoc when sensitivities do not match typical bacterial sensitivity patterns and to consult infectious disease specialists for assistance with therapeutic options considering its intrinsic vancomycin resistance. Our patient’s course was complicated due to a multitude of cardioembolic events. Considering these complications and the uncommon nature of the pathogenic organism, the patient underwent a truly remarkable recovery after undergoing coil embolization of the mycotic aneurysm and aortic valve and root replacement.

Conclusion

IE can prove to be devastating when left untreated. It is critical for clinicians to be aware of the many pathogenic organisms, including Leuconostoc species, and appropriate management strategies in order to avoid the myriad of complications that may ensue. It is also clear that a higher index of suspicion must be maintained in patients with multiple predisposing factors such as the patient in the case presented.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Starr J.A. Leuconostoc species-associated endocarditis. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:766–770. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.5.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García-Granja P.E., López J., Ladrón R., San Román J.A. Infective endocarditis due to Leuconostoc species. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2017:S1885–S5857. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2017.04.013. 30217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facklam R., Elliott J. Identification, classification, and clinical relevance of catalase-negative, Gram-positive cocci, excluding the Streptococci and Enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:479–495. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handwerger S., Horowitz H., Coburn K., Kolokathis A., Wormser G.P. Infection due to Leuconostoc species: six cases and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:602–610. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.4.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sampelayo T., Moreno S., Bouza E. Leuconostoc species as a cause of bacteremia: two case reports and a literature review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:505–509. doi: 10.1007/BF01963938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shelburne S., Greenberg S., Aslam S., Tweardy D. Successful ceftriaxone therapy of endocarditis due to penicillin non-susceptible viridans streptococci. J Infect. 2017;54:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baddour L., Wilson W., Bayer A., Fowler V., Tleyjeh I., Rybak M. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y., Liao C., Teng L., Hsueh P. Daptomycin susceptibility of unusual Gram-positive bacteria: comparison of results obtained by the Etest and the broth microdilution method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1570–1572. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01352-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swenson J., Facklam R., Thornsberry C. Antimicrobial susceptibility of vancomycin-resistant Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, and Lactobacillus species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:543–549. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.4.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang D. Timing of surgery in infective endocarditis. Heart. 2015;101:1786–1791. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]