Abstract

Radical chemistry is a very convenient way to produce polymer materials. Here, an application of a particular photoinduced radical chemistry is illustrated. Seven new carbazole derivatives Cd1–Cd7 are incorporated and proposed as high performance near-UV photoinitiators for both the free radical polymerization (FRP) of (meth)acrylates and the cationic polymerization (CP) of epoxides utilizing Light Emitting Diodes LEDs @405 nm. Excellent polymerization-initiating abilities are found and high final reactive function conversions are obtained. Interestingly, these new derivatives display much better near-UV polymerization-initiating abilities compared to a reference UV absorbing carbazole (CARET 9H-carbazole-9-ethanol) demonstrating that the new substituents have good ability to red shift the absorption of the proposed photoinitiators. All the more strikingly, in combination with iodonium salt, Cd1–Cd7 are likewise preferred as cationic photoinitiators over the notable photoinitiator bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phenylphosphine oxide (BAPO) for mild irradiation conditions featuring their remarkable reactivity. In particular their utilization in the preparation of new cationic resins for LED projector 3D printing is envisioned. A full picture of the included photochemical mechanisms is given.

Keywords: cationic polymerization, free radical polymerization, light emitting diodes (LEDs), photoinitiators, 3D printing

1. Introduction

Radical (photo) chemistry plays a significant role in the production of polymer materials. Due to their advantages, compared to thermal activation and their applications as a green technology, light activated polymerization reactions are experiencing an ever increasing development and have inspired a lot of work on the design of photoinitiators PIs and multicomponent photoinitiating systems PISs (see e.g., in recent papers and books [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] and references therein). One current approach concerns the adaptation of PIs to LED irradiation wavelengths and, among others, a particularly interesting application refers to 3D printing. PIs are able to produce radicals or cations under light exposure. Suitable PISs can have dual behavior: using the same system both a radical and a cationic photopolymerization can be carried out separately and/or together (like interpenetrating polymer networks or IPNs).

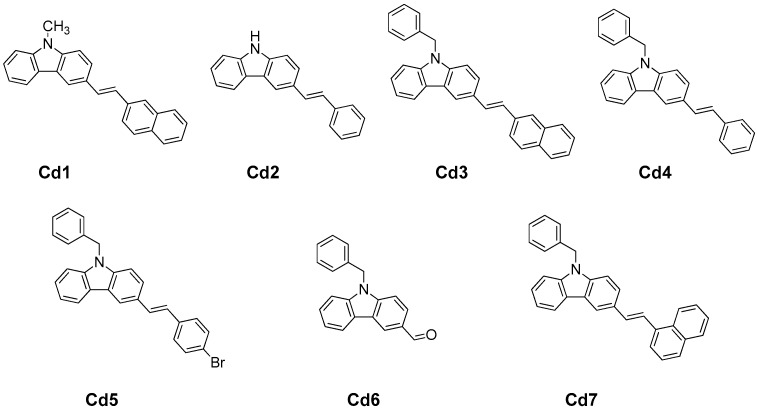

In a recent study [15], four new carbazole derivatives exhibiting long wavelength absorption have been proposed as PIs. As this kind of skeleton was particularly promising, seven new carbazole derivatives (Cds) Cd1–Cd7 exhibiting long wavelength absorption thanks to well selected substituents were synthesized (see Scheme 1); 9H-carbazole-9-ethanol (CARET) used previously in our papers [16,17,18] was chosen here as a reference carbazole derivative. The new carbazole derivatives were incorporated into two-component (PI/iodonium salt Iod) and sometimes into three-component (PI/Iod/amine) photoinitiating systems (PISs) to induce the formation of reactive species (radicals or radical cations) for free radical polymerization (FRP) and/or cationic polymerization (CP) under near-UV and visible light. Interestingly, the different substituents introduced on the carbazole skeleton highly affect the absorption as well as the photochemical/electrochemical properties of Cd1–Cd7. Obviously, this will pave the way to study the structure/reactivity/efficiency relationships of the studied carbazole derivatives as photoinitiators in CP and FRP. The use of these new high performance photosensitive systems in LED projector 3D printing experiments is also described. Finally, an insight into the involved mechanisms is provided.

Scheme 1.

The different carbazole derivatives (Cds) (denoted Cd1–Cd7) investigated in this study.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Experimental Results

2.1.1. Light Absorption Properties of Cd1–Cd7

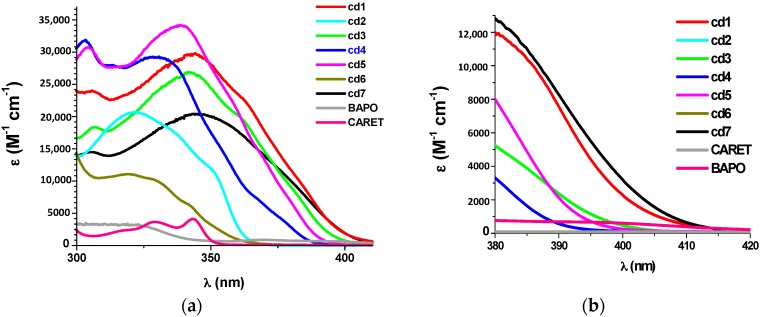

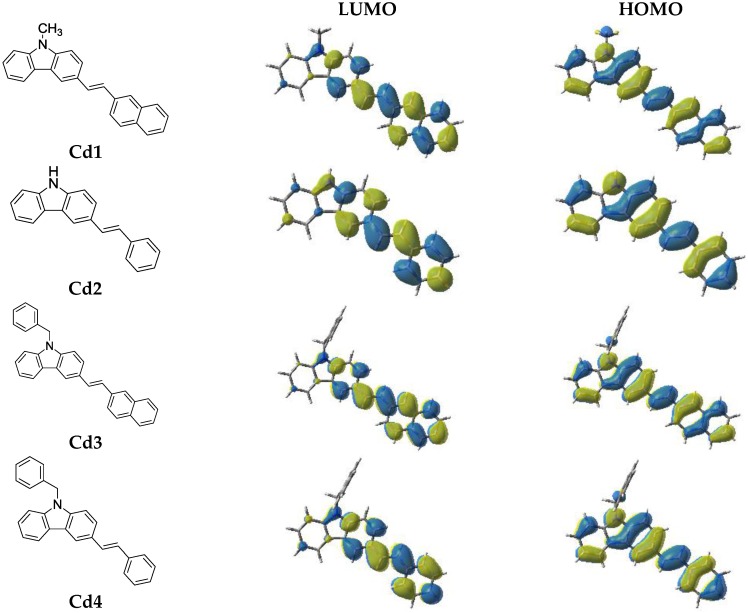

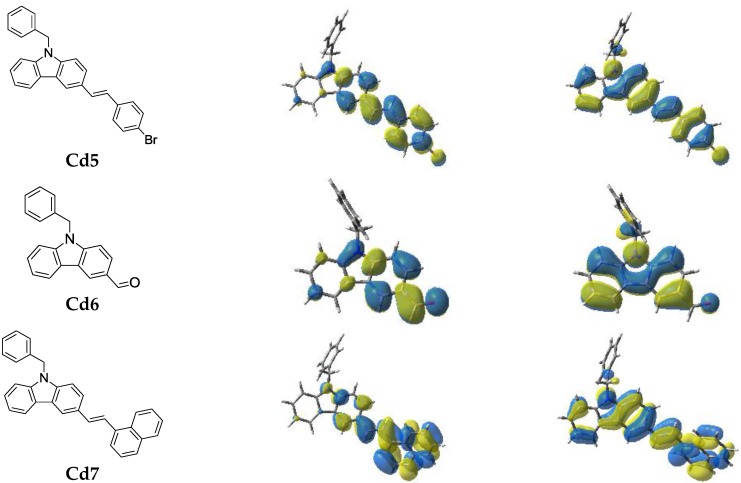

The ground state absorption spectra of the new proposed photoinitiators in dichloromethane (DCM) are shown in Figure 1 (see additionally Table 1). These compounds exhibit high molar extinction coefficients in the near UV (e.g., Cd7 ~20,500 M−1·cm−1 @345 nm and 1500 M−1·cm−1 @405 nm). Their absorptions in the 350–410 nm spectral range are interesting, guaranteeing a good overlap with the emission spectrum of the LED@405 nm used in this work. The optimized geometries and the frontier orbitals (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital—HOMO and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital—LUMO) are shown in Figure 2. Both the HOMO and LUMO are firmly delocalized all over the π system clearly showing a π→π* lowest energy transition. The extension of the π framework by means of various substituents on the carbazole moiety causes a reasonable shift in the spectrum (e.g., the presence of 3-(1-naphthylethenyl) group causes a bathochromic shift in the spectrum of Cd7, Figure 1, and Table 1). A significant difference in the HOMO structure of Cd3 and Cd7 is also observed. The clear bathochromic shift caused by the different substituents in Cd1–Cd7 is consummately anticipated and it follows the following order: Cd7~Cd1 > Cd3 > Cd5 > Cd4 > Cd2 > Cd6. For the reference carbazole derivative (CARET), with no substituent on the phenyl rings, a shorter wavelength absorption is found as well as lower extinction coefficients (e.g., no absorption for CARET@405 nm vs. ε ~1500 (M−1·cm−1) for Cd7 see in Table 1). Surprisingly, contrasted with the well known photoinitiator (BAPO), the new proposed structures Cd1–Cd7 exhibit much better light absorption properties in all the 350–410 nm range (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Absorption properties for Cd1–Cd7 vs. CARET and BAPO. (a) For short wavelength (300–400 nm); (b) for extended wavelengths, particularly between 380 and 415 nm.

Table 1.

Absorption properties for Cd1–Cd7 vs. CARET and BAPO (@405 nm).

| Cd1 | Cd2 | Cd3 | Cd4 | Cd5 | Cd6 | Cd7 | BAPO | CARET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε 1 | 1000 | n.a 2 | 180 | 90 | 140 | n.a 2 | 1500 | 500 | n.a 2 |

1 @405 nm (M−1·cm−1); 2 no absorption.

Figure 2.

Contour plots of HOMOs and LUMOs for the Cd structures optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

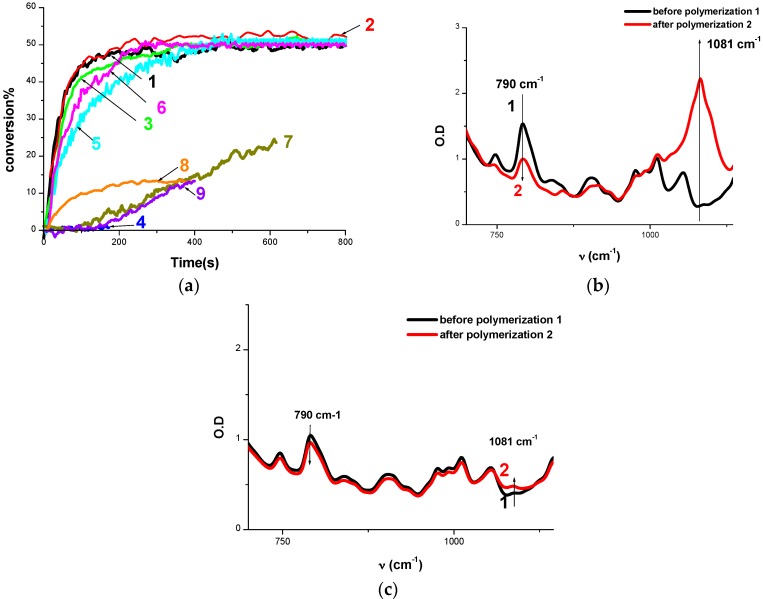

2.1.2. Cationic Photopolymerization (CP) of Epoxides

Upon LED@405 nm illumination, the cationic polymerization (CP) of epoxides (e.g., EPOX) under air using two-component photoinitiating systems based on Cd/Iod blends (0.5%/1% w/w) displays high effectiveness in term of final epoxy function conversion (FC) (e.g., FC 55% with Cd7; at t = 800 s; Figure 3a, band 1). The polyether network formation can clearly be observed at ~1080 cm−1 (Figure 3b) in the FTIR spectra. Iod alone does not initiate the polymerization, obviously demonstrating the role of Cd1–Cd7 in inducing the iodonium salt disintegration upon near UV light LED. Amazingly, high rates of polymerization (Rp) were obviously achieved with the Cd1–Cd7/Iod systems aside from Cd2/Iod and Cd6/Iod system contrasted with the CARET/Iod system set as a reference for which no polymerization happens. The correlation of Cd1–Cd7 with CARET is important as all photoinitiators are characterized by having of a carbazole moiety. Likewise, astoundingly, in comparison with the well-known BAPO/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w) system, both Cd1 and Cd7, aside from Cd2 and Cd6, are discovered much preferable photoinitiators over BAPO (Figure 3a, curve 8 for BAPO contrasted with curve 1 for Cd7). This information demonstrates the outstanding predominance of the new carbazoles as far as efficiencies over the well-known BAPO (i.e., the polyether peaks are not observed neither for CARET/Iod e.g., in Figure 3c, nor for BAPO/Iod contrasted with the Cd7/Iod system as e.g., in Figure 3b). The efficiency trend for CP using LED@405 nm follows the following order: Cd7~Cd1 > Cd3 > Cd5 > Cd4 > BAPO > Cd6~Cd2 > CARET (Table 2). RT-FTIR monitoring for curves 4, 7, 8 and 9 were stopped before 800 s as very poor kinetics were observed (conversion below 10% after 200 s), characteristics of very poor PIS efficiencies (strongly inhibited by oxygen). Clearly, this is straightforwardly related to the absorption properties of the carbazole derivatives as Cd7 and Cd1 are the leaders in the efficiency trend and having higher extinction coefficients at 405 nm contrasted with the others (see Table 1).

Figure 3.

(a) Polymerization profiles of EPOX (epoxy function conversion vs. irradiation time) upon exposure to the LED@405 nm under air in the presence of different photoinitiating systems: (1) Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (2) Cd1/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (3) Cd3/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (4) Cd2/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (5) Cd4/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (6) Cd5/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (7) Cd6/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (8) BAPO/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (9) CARET/Iod (1%/1% w/w); IR spectra recorded before and after polymerization using: (b) Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (c) CARET/Iod (1%/1% w/w). The irradiation starts at t = 10 s.

Table 2.

Function conversions (FC): epoxy for EPOX; acrylate for TMPTA and methacrylate for BisGMA/TEGDMA using different photoinitiating systems; LED@405 nm for irradiation.

| Cd1 | Cd2 | Cd3 | Cd4 | Cd5 | Cd6 | Cd7 | BAPO | CARET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPOX 1 | 44% | 0% | 41% | 27% | 30% | 37% | 44% | 10% | 1% |

| TMPTA 2 | 46% | 0% | 34% | 34% | 43% | 28% | 57% | 60% | |

| BisGMA/TEGDMA 3 | 57% | 0% | 60% |

1 Epoxy function Conversion FC (%) for EPOX (at t = 100 s) (0.5% PI + 1% Iod); 2 Acrylate function conversion FC for TMPTA (%) (at t = 100 s) (0.5% PI + 1% Iod); excepted (1% CARET + 1% Iod); 3 Methacrylate conversion FC for BisGMA/TEGDMA (%) (at t = 100 s) (0.5% PI + 1% Iod).

2.1.3. Free Radical Photopolymerization

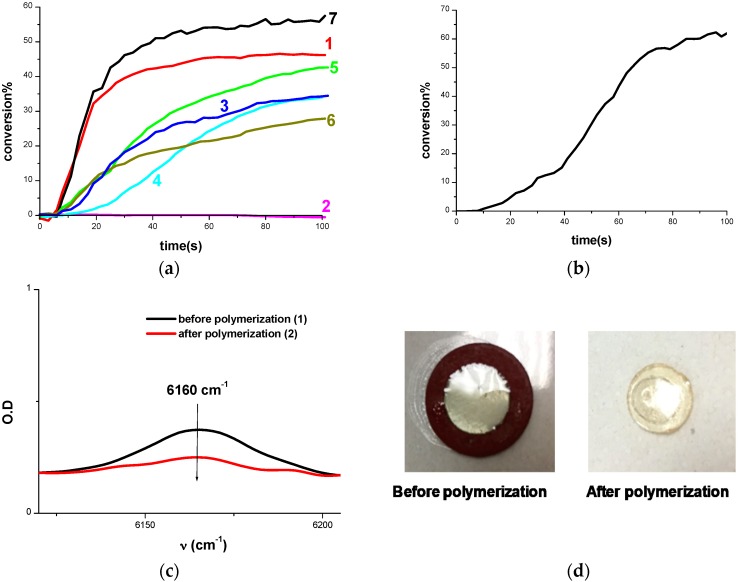

• Photopolymerization of Acrylates

The FRP of TMPTA thin films in laminate initiated from diverse Cd/Iod couples is very effective in some cases using the LED@405 nm, while Iod alone obviously does not initiate the polymerization. Typical acrylate function conversion-time profiles are given in Figure 4 and the FCs are outlined in Table 2. Best FCs are achieved when using Cd7/Iod and Cd1/Iod (~57% and 46% respectively at t = 100 s), that’s why these structures will be of more deeply studied in the rest of the manuscript. Strikingly, the reactivity trend follows the order in-line with what observed for the CP process: Cd7 > Cd1 > Cd5 > Cd3 > Cd4 > Cd6~Cd2.

Figure 4.

(a) Polymerization profiles of TMPTA (acrylate function conversion vs. irradiation time) in laminate upon exposure to LED@405 nm in the presence of: (1) Cd1/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (2) Cd2/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (3) Cd3/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (4) Cd4/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (5) Cd5/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (6) Cd6/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (7) Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (b) Polymerization profiles of BisGMA/TEGDMA (70%/30%) (methacrylate function conversion vs. irradiation time) (1.4 mm film thick sample) under air upon exposure to LED@405 nm in the presence of Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (c) Near IR spectra recorded before and after polymerization of BisGMA/TEGDMA using Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w); (d) Photos of BisGMA/TEGDMA film (1.4 mm thick) upon irradiation with the LED@405 nm for 100 s in the presence of Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w) under air before and after polymerization.

• Photopolymerization of Methacrylates

Interestingly, the Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w) couple effectively initiates the FRP of a mix of methacrylates (BisGMA/TEGDMA 70%/30% w/w) under air (1.4 mm thick example) upon illumination with the LED@405 nm, as shown in Figure 4d. Remarkably, a straightforward tack free polymer is produced even in thick examples (Figure 4d).

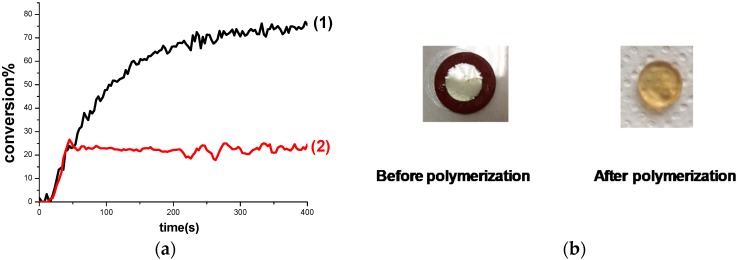

2.1.4. Synthesis of Inter-Penetrated Networks (IPNs) through Photopolymerization

The Cd/Iod two-component PIS can jointly create both free radicals (Ph•) and radical cations (Cd•+) simultaneously upon visible light exposure using LED@405 nm and hence can be utilized for the synthesis of IPNs from acrylate/epoxy combinations (Figure 5a). Effectively, the synthesis of a thick 1.4 mm tack free coating was performed under air (Figure 5b). Very high final function conversion of acrylate functional group compared to the epoxy functional group (FCs ≈ 76% and 23% for the acrylate and the epoxide, band 1 and band 2 in Figure 5a, respectively). In reality, this behaviour which can be credited to the more receptive radicals (Ph•) in the event of free radical polymerization contrasted with cationic polymerization (where cations are starting species) is reported in the literature [19].

Figure 5.

(a) Polymerization profiles of TMPTA/EPOX blend (acrylate and epoxy function conversions vs. irradiation time) under air thick sample 1.4 mm upon exposure to LED@405 nm in the presence of Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w): (1) TMPTA; (2) EPOX; (b) Photos of TMPTA/EPOX film (1.4 mm thick) upon irradiation with the LED@405 nm for 400 s in the presence of Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w) under air before and after polymerization.

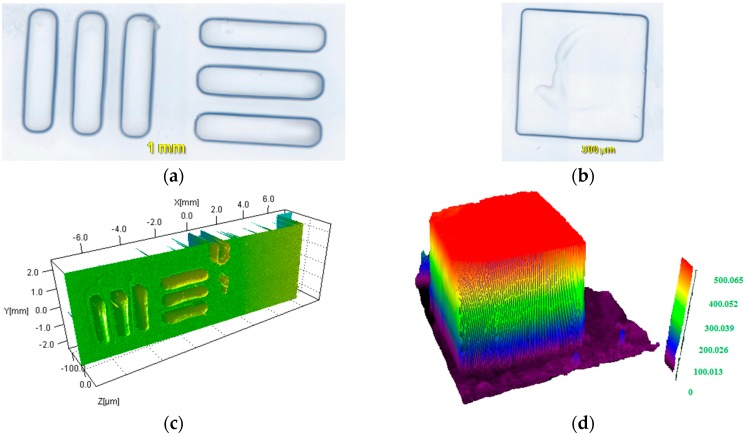

2.1.5. Surface Patterning or 3D Printing Using Cd1–Cd7 Based System upon LED@405 nm Projector

For 3D printing tests, a LED projector @405 nm (110 mW/cm2, Thorlabs, Gmbh, Germany) was utilized. A similar intensity on the surface of the specimen and a similar emission spectrum for the LEDs used in 3D printing and in monitoring FTIR tests were used for purpose of comparison. In Figure 6, some 3D printing tests were done using the LED projector illumination using the Cd7/Iod (0.5%/1% w/w) PIS, which is extremely responsive in the cationic polymerization of epoxides (see above) under air. Remarkably, the high photosensitivity of this resin permits an effective polymerization process in the illuminated area. This LED projector tests demonstrate a favorable element over other laser based 3D printing techniques as the whole layer is illuminated at one time. The fast cationic process upon exposure to the LED projector @405 nm likely outperform the radical process by diminishing the shrinkage generally observed in the latter. Thin 3D objects (25–50 μm) and in addition thicker ones (0.45 mm) can be effectively generated through the LED projector technique (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cationic photopolymerization experiments using LED projector @405 nm: (a,b) patterns (c) Profilometry characterization for a thin pattern obtained (thin samples 0.02 mm); (d) observation (numerical optical microscopy) of pattern written in 3D for a thicker sample (0.5 mm).

2.2. Photochemical Mechanisms

2.2.1. Steady State Photolysis

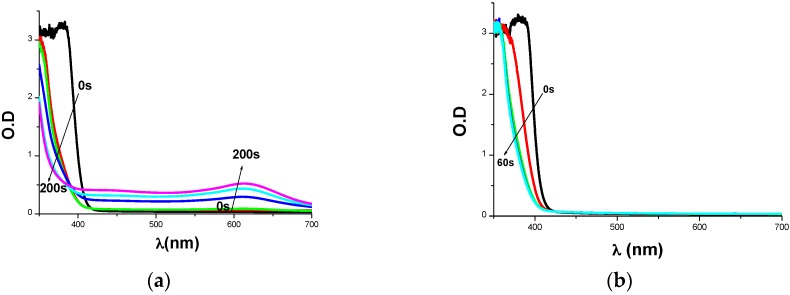

The steady state photolysis of Cd1–Cd7/Iod in acetonitrile is quick compared to the photolysis of Cds alone (e.g., Cd7/Iod in Figure 7a versus Cd7 alone in Figure 7b). A new photo-product (described by a noteworthy new absorption for λ > 550 nm; Figure 7a) is formed and expected due to the Cd7/Iod.

Figure 7.

(a) Cd7/Iod photolysis upon exposure to LED@405 nm and (b) Photolysis of Cd7 in the absence of Iod.

2.2.2. Fluorescence Quenching, Laser Flash Photolysis (LFP), Cyclic Voltammetry and ESR Experiments

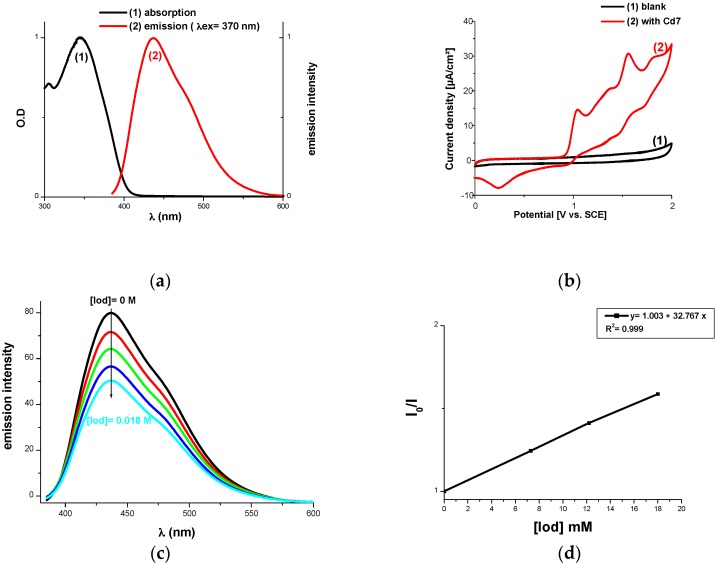

Fluorescence experiments in acetonitrile are shown in Figure 8 for Cd7. The intersection point of the absorption and fluorescence spectra permits the determination of the first singlet excited state energies (ES1) (Table 3; e.g., ES1 for Cd7 Figure 8a). Ideal fluorescence quenching processes were proven by high estimations of the Stern Volmer coefficients leading to Φet in (Equation (1)) (Table 3, Figure 8c,d). Highly favorable free energy changes for the electron transfer reaction were noted between carbazole derivatives and Iod (e.g., ΔGet = −1.95 eV for Cd7; the oxidation potential for Cd7 was determined by cyclic voltammetry in Figure 8b), electron transfer quantum yields from S1 (Φet) were computed by Equation (1): Φet ~ 0.43 with Cd7). Efficient processes can also be expected from the triplet state of Cd (ΔGet (T1) < 0 eV; Table 3); but the singlet state pathway is probably more favorable due to the high value of Φet from S1 found above:

| Φet = Ksv [Iod]/(1 + Ksv[Iod]) | (1) |

Figure 8.

(a) Singlet state energy determination; (b) Cyclic voltammetry for the Cd7 oxidation; (c) Fluorescence quenching of Cd7 with Iod; (d) Stern-Volmer treatment of the lifetime quenching of *Cd7 in the presence of Iod.

Table 3.

Parameters characterizing the chemical mechanisms associated with the Cd1–Cd7/Iod systems in acetonitrile.

| Eox (eV) 1 | ES1 (eV) | ΔGetS1 (eV) | ET1 (eV) 2 | ΔGetT1 2 (eV) | Φet (S1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd1 | 0.92 | 3.17 | −2.05 | 1.97 | −0.85 | 0.34 |

| Cd2 | 1.06 | 3.5 | −2.22 | 1.99 | −0.73 | 0.5 |

| Cd3 | 0.97 | 3.2 | −2.02 | 1.97 | −0.81 | 0.41 |

| Cd4 | 0.96 | 3.35 | −2.19 | 1.99 | −0.83 | 0.5 |

| Cd5 | 0.99 | 3.25 | −2.06 | 1.97 | −0.79 | |

| Cd6 | 1.49 | 3.5 | −1.81 | 3.04 | −1.36 | |

| Cd7 | 0.98 | 3.13 | −1.95 | 1.89 | −0.72 | 0.43 |

1 Oxidation potentials for Cd1–Cd7 (this work); 2 from molecular orbital calculations (uB3LYP/6-31G* level of theory).

The favorable quenching process of carbazole derivatives by Iod is depicted by the reactions r1 and r2:

| Cd→ *Cd (hυ) | (r1) |

| *Cd + Ar2I+ → Cd●+ + Ar2I● → Cd●+ + Ar● + ArI | (r2) |

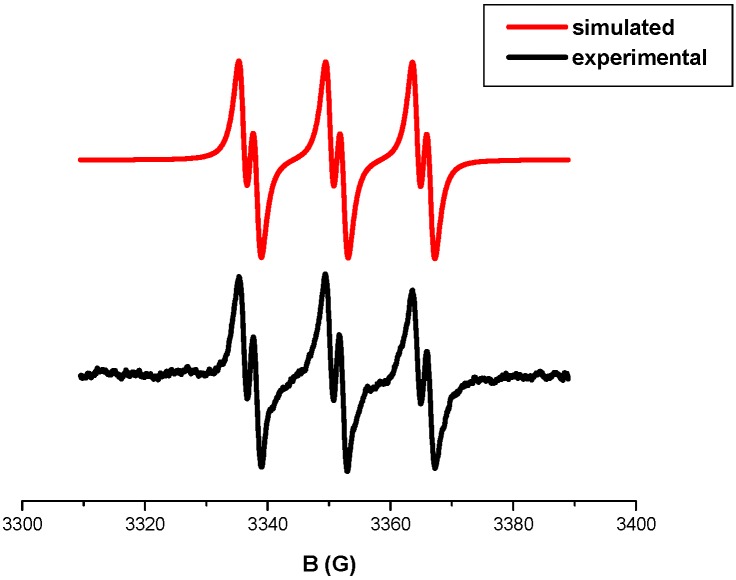

The presence of Ar● (r2) is fully confirmed by ESR results. Indeed, the phenyl radicals (Ar●) were easily detected as PBN/Ar● radical adducts in the irradiation of a Cd7/Iod solution in ESR-ST experiments (Figure 9) i.e., the simulation of the experimental ESR spectrum yields the hyperfine coupling constants (hfcs): aN = 14.13 G and aH = 2.21 G typical for the PBN/Ph● radical adducts.

Figure 9.

ESR-ST spectra obtained upon irradiation (LED@405 nm) of a Cd7/Iod solution, experimental (lower spectrum), and simulated (upper spectrum) in tert-butyl benzene as a solvent.

2.2.3. Structure/Reactivity/Efficiency Relationship

In both CP and FRP, the studied carbazole derivatives follow the same trend of efficiency in terms of final conversion of both acrylate functional groups as well as epoxy functional groups, respectively. In fact, the efficiency trend of the carbazole derivatives more or less follows their absorption trend. Clearly, both Cd7 and Cd1 are the best photoinitiators in terms of efficiency under LED@405 nm irradiation (see above in parts 2 and 3), and at the same time they are characterized by relatively higher absorption ability at this range of wavelengths. On the other hand, the ΔGs of electron transfer of all Cds as well electron transfer quantum yields (Table 3) are relatively similar and thus can be excluded for being the key factor for the Structure/Reactivity/Efficiency relationships of these derivatives as they are rather similar in the Cd1–Cd7 series. Therefore, the key factor affecting the reactivity and efficiency of these carbazole derivatives as PIs is their absorption properties since as better absorption of Cd7 and Cd1 of the light from LED@405 nm is observed, these carbazole derivatives exhibit the best performance. The following table (Table 4) summarizes the trends in magnitude of absorption, efficiencies in both CP and FRP.

Table 4.

Trends of bathochromic shift, Cationic polymerization efficiency, and Free radical polymerization efficiency.

| Trend of bathochromic shift | Cd7~Cd1 > Cd3 > Cd5 > Cd4 > Cd2 > Cd6 |

| Trend of CP efficiency | Cd7~Cd1 > Cd3 > Cd5 > Cd4 > Cd6~Cd2 |

| Trend of FRP efficiency | Cd7 > Cd1 > Cd5 > Cd3 > Cd4 > Cd6~Cd2 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Compounds

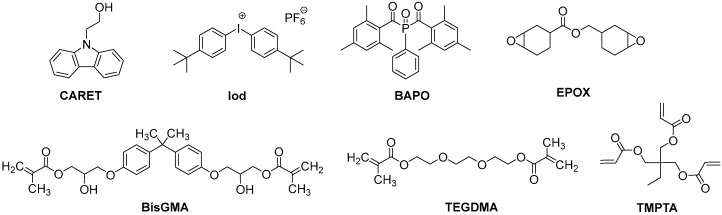

9H-Carbazole-9-ethanol (CARET) and phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) (Scheme 2) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bis-(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium hexafluorophosphate (Iod or Speedcure 938) and bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phenylphosphine oxide (BAPO or speedcure BPO) were obtained from Lambson (Lambson Ltd., Wetherby, UK). Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) and 3,4-epoxycyclohexylmethyl 3,4-epoxycyclo-hexylcarboxylate (EPOX; Uvacure 1500) were obtained from Allnex (Frankfurt, Germany) and used as benchmark monomers for radical and cationic photopolymerization. Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate (BisGMA) and triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich and used with the highest purity available. The full procedures for the synthesis of Cd1–Cd7, are presented in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 2.

Other used chemical compounds.

3.2. Irradiation Sources

The following Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) were used as irradiation sources: (i) LED@375 nm—incident light intensity at the sample surface: I0 ≈ 40 mW cm−2; (ii) LED@405 nm (I0 ≈ 110 mW cm−2).

3.3. Free Radical (FRP) and Cationic (CP) Photopolymerization

The two-component photoinitiating systems (PISs) are mainly based on Cds/Iodonium salt (0.5%/1% w/w) for both CP and FRP. The weight percent of the photoinitiating system is calculated from the monomer content. The photosensitive thin-film formulations (~25 µm of thickness) were deposited on BaF2 pellets under air for the CP of EPOX while for the FRP of TMPTA and BisGMA/TEGDMA, it was done in laminate (the formulation is sandwiched between two polypropylene films to reduce the O2 inhibition). The 1.4 mm thick samples of BisGMA/TEGDMA were polymerized under air.

Excellent solubility of all carbazole derivatives except for Cd6 were observed in EPOX monomer. The decrease of the epoxy group content and the double bond content of (meth)acrylate functions were continuously followed by real time FTIR spectroscopy (JASCO FTIR 4100, Oklahoma City, OK, USA) at about 790 cm−1 and 1630 cm−1, respectively. The evolution of the methacrylate characteristic peak for the thick samples (1.4 mm) was followed in the near infrared range at ~6160 cm−1. The procedure used to monitor the photopolymerization profile has been described in detail in [20,21].

3.4. Redox Potentials

The oxidation potentials (Eox vs. SCE) for the different carbazole derivatives were measured in acetonitrile by cyclic voltammetry with tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate 0.1 M as the supporting electrolyte. The free energy change ∆Get for an electron transfer reaction was calculated from the Rehm-Weller equation (Equation (2)) [22] where Eox, Ered, E* and C are the oxidation potential of the electron donor, the reduction potential of the electron acceptor, the excited state energy level and the coulombic term for the initially formed ion pair, respectively. C is neglected as usually done in polar solvents:

| ∆Get = Eox − Ered − E* + C | (2) |

3.5. ESR Spin Trapping (ESR-ST) Experiments

The ESR-ST experiments were carried out using an X-Band spectrometer (EMX-Plus, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). LED@405 nm was used as irradiation source for triggering the production of radicals at room temperature (RT) for N2 saturated toluene solutions and trapped by phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) according to a procedure described by us in details [23]. The ESR spectra simulations were carried out with the PEST WINSIM program.

3.6. Absorption Experiments

The UV-vis absorption properties of the compounds were studied using a JASCO V730 spectrophotometer.

3.7. Fluorescence Experiments

The fluorescence properties of the compounds were studied using a JASCO FP-6200 fluorimeter.

3.8. Computational Procedure

Molecular orbital calculations were carried out with the Gaussian 03 suite of programs [24,25]. The electronic absorption spectra for the different compounds were calculated with the time-dependent density functional theory at the MPW1PW91/6-31g(d) level of theory on the relaxed geometries calculated at the UB3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

3.9. 3D Printing Experiments

For 3D printing experiments, a LED projector @405 nm (Thorlabs) was used. The photosensitive cationic resin was polymerized under air and the generated patterns analyzed by an opto-digital microscope (DSX-HRSU from Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) or by profilometry. The procedure was presented in [26].

4. Conclusions

In the present paper, the carbazole scaffold is proposed as an excellent precursor for the development of new photoinitiators using near-UV and visible wavelength LEDs for the photoinitiation of both the cationic polymerization of epoxides and the free radical polymerization of (meth)acrylates. High final conversions and polymerization rates are achieved. Examples of using these new initiating frameworks in cationic photocurable resins for LED projector 3D printing are given. Basically, the primary processes involve the simultaneous production of radicals and radical cations that can be applied both in radical chemistry and/or cationic chemistry. New photoinitiating systems based on carbazole derivatives capable to be operated at various illumination wavelengths or that can be incorporated in 3D printing resins will be reported in future papers.

Acknowledgments

The Lebanese group would like to thank ‘The Association of Specialization and Scientific Guidance’ (Beirut, Lebanon) for funding and supporting this scientific work. The authors thank the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche” (ANR) for the grant “FastPrinting”.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials are available online, the synthesis of Cd1–Cd7, the procedures are fully presented in supporting information.

Author Contributions

Assi Al Mousawi and Patxi Garra performed the polymerization experiments and the photophysical characterizations of the different photoinitiators, analyzed the whole data sets and wrote the first draft of the paper. Frédéric Dumur and Thanh-Tuan Bui did the synthesis of the different photoinitiators reported in this work and characterized the chemical structures of the different molecules by usual techniques. Didier Gigmes and Fabrice Goubard contributed to the molecular design of the photoinitiators. Bernadette Graff did the theoretical calculations and interpreted the data. Jean Pierre Fouassier and Jacques Lalevée conceived the project and contributed to all aspects of the study and writing of the final manuscript. Joumana Toufaily and Tayssir Hamieh contributed to the supervision of Assi Al Mousawi as co-advisors, assisted in obtaining the Ph.D. grants and editing the manuscript and contributed to the project with fruitful discussions. All authors discussed the contents of the manuscript and approved the submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds Cd1–Cd7 are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Fouassier J.-P., Lalevée J. Photoinitiators for Polymer Synthesis, Scope, Reactivity, and Efficiency. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fouassier J.P. Photoinitiation, Photopolymerization and Photocuring: Fundamentals and Applications. Gardner Publications; New York, NY, USA: 1995. ISBN-10 1569901465. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietliker K.A. Compilation of Photoinitiators Commercially Available for UV Today. Sita Technology Ltd.; London, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson S. Exploring the Science, Technology and Application of UV and EB Curing. Sita Technology Ltd.; London, UK: 1999. ISBN-10 0947798412. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins A. In: Photoinitiators for Free Radical Cationic and Anionic Photopolymerisation. 2nd ed. Crivello J.V., Dietliker K., Bradley G., editors. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lalevée J., Fouassier J.-P., editors. Dyes and Chromophores in Polymer Science. ISTE Wiley; London, UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietlin C., Schweizer S., Xiao P., Zhang J., Morlet-Savary F., Graff B., Fouassier J.-P., Lalevée J. Photopolymerization upon LEDs: New Photoinitiating Systems and Strategies. Polym. Chem. 2015;6:3895–3912. doi: 10.1039/C5PY00258C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zivic N., Bouzrati-Zerelli M., Kermagoret A., Dumur F., Gigmes D., Fouassier J.-P., Lalevée J. Photocatalysts in Polymerization Reactions. ChemCatChem. 2016;8:1617–1631. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201501389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treat N.J., Fors B.P., Kramer J.W., Christianson M., Chiu C.-Y., Read de Alaniz J., Hawker C.J. Controlled Radical Polymerization of Acrylates Regulated by Visible Light. ACS Macro Lett. 2014;3:580–584. doi: 10.1021/mz500242a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan X., Lamson M., Yan J., Matyjaszewski K. Photoinduced Metal-Free Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization of Acrylonitrile. ACS Macro Lett. 2015;4:192–196. doi: 10.1021/mz500834g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyer C., Corrigan N.A., Jung K., Nguyen D., Nguyen T.-K., Adnan N.N.M., Oliver S., Shanmugam S., Yeow J. Copper-Mediated Living Radical Polymerization (Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization and Copper(0) Mediated Polymerization): From Fundamentals to Bioapplications. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:1803–1949. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tasdelen M.A., Yilmaz G., Iskin B., Yagci Y. Photoinduced Free Radical Promoted Copper(I)-Catalyzed Click Chemistry for Macromolecular Syntheses. Macromolecules. 2012;45:56–61. doi: 10.1021/ma202438w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corrigan N., Xu J., Boyer C. A Photoinitiation System for Conventional and Controlled Radical Polymerization at Visible and NIR Wavelengths. Macromolecules. 2016;49:3274–3285. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeow J., Shanmugam S., Corrigan N., Kuchel R.P., Xu J., Boyer C. A Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly Approach to Nanoparticles Loaded with Singlet Oxygen Generators. Macromolecules. 2016;49:7277–7285. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Mousawi A., Dumur F., Garra P., Toufaily J., Hamieh T., Graff B., Gigmes D., Fouassier J.P., Lalevée J. Carbazole Scaffold Based Photoinitiator/Photoredox Catalysts: Toward New High Performance Photoinitiating Systems and Application in LED Projector 3D Printing Resins. Macromolecules. 2017;50:2747–2758. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al Mousawi A., Dietlin C., Graff B., Morlet-Savary F., Toufaily J., Hamieh T., Fouassier J.P., Chachaj-Brekiesz A., Ortyl J., Lalevée J. Meta-Terphenyl Derivative/Iodonium Salt/9H-Carbazole-9-Ethanol Photoinitiating Systems for Free Radical Promoted Cationic Polymerization upon Visible Lights. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016;217:1955–1965. doi: 10.1002/macp.201600224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Mousawi A., Poriel C., Dumur F., Toufaily J., Hamieh T., Fouassier J.P., Lalevée J. Zinc Tetraphenylporphyrin as High Performance Visible Light Photoinitiator of Cationic Photosensitive Resins for LED Projector 3D Printing Applications. Macromolecules. 2017;50:746–753. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Mousawi A., Kermagoret A., Versace D.-L., Toufaily J., Hamieh T., Graff B., Dumur F., Gigmes D., Fouassier J.P., Lalevée J. Copper Photoredox Catalysts for Polymerization upon near UV or Visible Light: Structure/Reactivity/Efficiency Relationships and Use in LED Projector 3D Printing Resins. Polym. Chem. 2017;8:568–580. doi: 10.1039/C6PY01958G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fouassier J.P., Lalevée J. Photochemical Production of Interpenetrating Polymer Networks; Simultaneous Initiation of Radical and Cationic Polymerization Reactions. Polymers. 2014;6:2588–2610. doi: 10.3390/polym6102588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalevée J., Blanchard N., Tehfe M.-A., Peter M., Morlet-Savary F., Gigmes D., Fouassier J.P. Efficient Dual Radical/Cationic Photoinitiator under Visible Light: A New Concept. Polym. Chem. 2011;2:1986–1991. doi: 10.1039/c1py00140j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalevée J., Blanchard N., Tehfe M.-A., Peter M., Morlet-Savary F., Fouassier J.P. A Novel Photopolymerization Initiating System Based on an Iridium Complex Photocatalyst. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011;32:917–920. doi: 10.1002/marc.201100098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehm D., Weller A. Kinetics of Fluorescence Quenching by Electron and H-Atom Transfer. Isr. J. Chem. 1970;8:259–271. doi: 10.1002/ijch.197000029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lalevée J., Blanchard N., Tehfe M.-A., Morlet-Savary F., Fouassier J.P. Green Bulb Light Source Induced Epoxy Cationic Polymerization under Air Using Tris(2,2′-bipyridine)ruthenium(II) and Silyl Radicals. Macromolecules. 2010;43:10191–10195. doi: 10.1021/ma1023318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foresman J.B., Frisch A. Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods. 2nd ed. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Zakrzewski V.G., Montgomery J.A., Stratmann J.R.E., Burant J.C., et al. Gaussian 03. Gaussian, Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA, USA: 2003. Revision B.03. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J., Dumur F., Xiao P., Graff B., Bardelang D., Gigmes D., Fouassier J.P., Lalevée J. Structure Design of Naphthalimide Derivatives: Toward Versatile Photoinitiators for Near-UV/Visible LEDs, 3D Printing, and Water-Soluble Photoinitiating Systems. Macromolecules. 2015;48:2054–2063. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.