Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM) share a common pathophysiology. However, diabetes mellitus is a complex disease, and T2DM and PTDM have different etiologies. T2DM is a metabolic disorder, characterized by persistent hyperglycemia, whereas PTDM is a condition of abnormal glucose tolerance, with variable onset after organ transplant. The KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 gene encode potassium channels, which mediate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, and KCN gene mutations are correlated with the development of diabetes. However, no studies have been carried out to establish an association between KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 gene polymorphisms and T2DM and PTDM. Therefore, our study was aimed at the identification of the role of KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 gene polymorphisms associated with T2DM and the risk of developing PTDM in the Asian Indian population. We have carried out a case–control study including 250 patients with T2DM, 250 control subjects, 42 patients with PTDM and 98 subjects with non-PTDM. PCR-RFLP analysis was carried out following the isolation of genomic DNA from EDTA-blood samples. The results of the present study reveal that two single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs2283228 and rs5210, of the KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 genes, respectively) are associated with both T2DM and PTDM. The results of our study suggest a role of KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 gene variants in the increased risk of T2DM and PTDM in the Asian Indian population.

Keywords: Asian Indians, KCNJ11, KCNQ1, PTDM, T2DM

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and post-transplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM), the latter also known as new-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT), are two major forms of multifactorial metabolic disorder. T2DM is a chronic disease, characterized by insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells1; PTDM is similar to T2DM in this respect. PTDM is not a separate disease on its own, but a symptom of an underlying metabolic disorder.2 Renal transplant (RT) recipients with PTDM/NODAT exhibit similar complications to those of T2DM patients in the general population, but at an accelerated rate of onset.3 Up until now, no clear risk factors for PTDM have been established. However, the following characteristics that appear to predispose patients to the development of PTDM have been identified: age, race, ethnicity, obesity, cadaver-donor kidney transplant, hepatitis C infection, metabolic syndrome, glucose intolerance, and immunosuppressive agents/drugs.4, 5 Earlier reports have concluded that a family history of T2DM increases the risk of PTDM up to seven-fold. The use of immunosuppressive medications, such as calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin and tacrolimus) and corticosteroids, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of PTDM.6, 7

Several papers have reported that insulin resistance is an important factor in the pathophysiology of PTDM; a defect in insulin secretion may also play a role in the development of the disease.2, 3, 8 Genome wide association studies (GWASs) identified several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are associated with susceptibility to T2DM.9, 10, 11 A GWAS has identified a mutation in the potassium voltage-gated channel, KQT-like subfamily, member 1 (KCNQ1) gene as an important disease-susceptibility factor associated with the pathogenesis of diabetes in Asian ethnic groups.12 KCNQ1 is present in adipose tissue and mediates insulin secretion; the mutation of the KCNQ1 gene has been shown to be associated with susceptibility to T2DM13 and to PTDM.11, 14 Candidate-gene studies have provided strong evidence that a common variant of the potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 11 (KCNJ11) gene is also associated with T2DM15 and PTDM.16 The variants of both the KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 genes are associated with reduced depolarization-evoked insulin exocytosis. In order to ascertain whether impaired β-cell function plays an important role in T2DM and PTDM, we examined the potential effect of these previously associated KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 variants on the risk of T2DM and PTDM following RT, in Asian Indian patients.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethical committee of Kamineni Hospital, Hyderabad, India, and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients who participated in the study.

Study design

This was a case–control study carried out in the Department of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Kamineni Hospital, Hyderabad, India. The study enrolled 640 Asian Indian subjects, 250 patients with T2DM, 250 healthy controls, and 140 patients who had undergone RT and been administered calcineurin inhibitors for >3 months. All the RT patients underwent routine follow up at the Department of Nephrology, Kamineni Hospital; 42 of these patients developed PTDM/NODAT later, as diagnosed by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria17, 18 and were included in the study, whereas the remaining 98 were termed as non-PTDM patients and were no longer included. All the healthy controls were selected from the general population visiting the hospital, based on their having normal blood glucose levels and being non-obese. The inclusion or exclusion of T2DM cases, healthy controls, and RT patients has been described in our previous publication.18, 19

Blood test

A total of 5 mL of peripheral blood was collected from the T2DM patients and healthy controls: 3 mL of the serum sample was used for biochemical analyses to confirm the disease diagnosis of T2DM patients, and 2 mL of the EDTA-blood sample was used for the molecular analysis of all the subjects who participated in the study. The clinical and biochemical assessments of T2DM cases and control subjects have been described in our previous studies.19

PCR and RFLP analyses

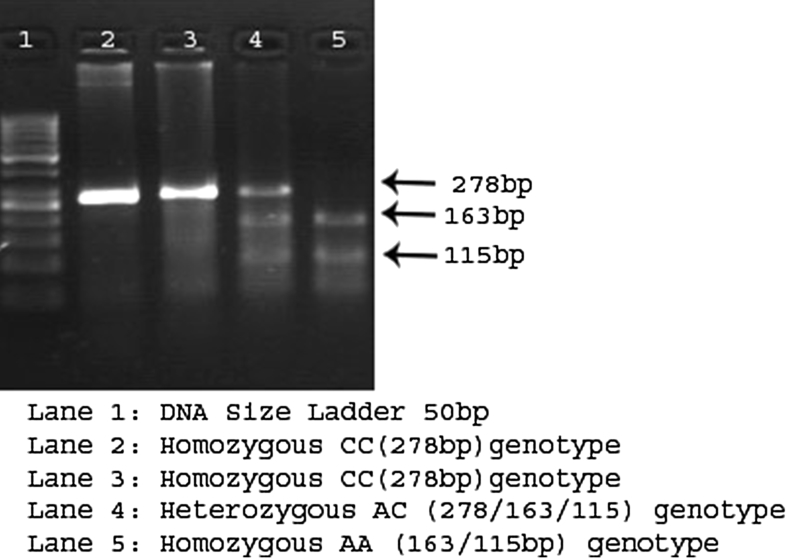

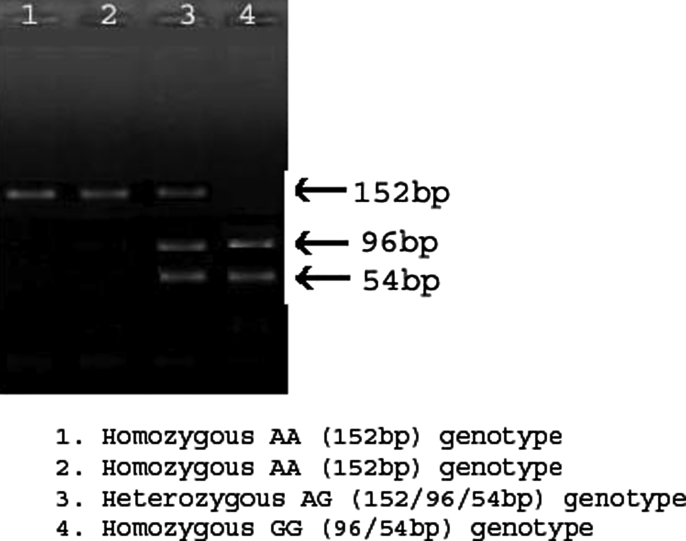

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral leucocytes using the salting-out technique, routinely used in our laboratory, as previously described.20 The DNA samples were stored at −80 °C until processed. Genotyping for KCNQ1 (rs2283228) and KCNJ11 (rs5210) variants was carried out via PCR-RFLP in a 25 μL reaction (Bangalore Genei kit; Bangalore Genei Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, Karnataka, India), using an Applied Biosystems thermal cycler machine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The primers for both the SNPs have been published.21, 22 Primers for PCR analyses were synthesized by Bio Serve Biotechnologies (BioServe Biotechnologies, Ltd., Hyderabad, India). The PCR procedure for both SNPs involved DNA denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, amplification by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 45 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The restriction enzymes, BsrI (A↓CTGGT) and Hpy1888III (TCCT↓GA) (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA), were first tested with bacteriophage λ DNA to confirm their specificity. BsrI was used to digest KCNQ1 PCR products and Hpy1888III was used to digest KCNJ11 PCR products for 4 h at 37 °C in a 20 μL reaction containing 2.5 μL of distilled water, 10 units of restriction enzyme per 15 μL of PCR product, and 2 μL of the appropriate restriction enzyme buffer. The digested PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 3.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Digested PCR products of KCNQ1 on 3% agarose gel.

Figure 2.

Depiction of digestion of KCNJ11 products on 3% agarose.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS software, version 21.0, for Windows (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA). Allele and genotype frequencies were compared between patients and controls using the χ2 test or a two-sided Fisher's exact test (p < 0.05 was considered significant). The χ2 test was used to compare genotype frequencies in T2DM patients vs. controls, and PTDM patients vs. controls, assuming both additive and recessive models. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was measured using the χ2 test for goodness of fit. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant disequilibrium.

Results

Characteristics of the T2DM patients

This study comprised two groups, 250 T2DM patients and 250 healthy controls, from the South Indian population residing in Telangana or Andhra Pradesh; the comparison between the anthropometric and clinical characteristics of the study groups is shown in Table 1. The average age of the T2DM patients was (57.19 ± 8.22) years with a mean body mass index (BMI) of (27.5 ± 4.1) kg/m2, whereas the average age of the controls was (53.93 ± 6.32) years with a mean BMI of (25.8 ± 3.9) kg/m2. There was a significant difference in the levels of fasting blood sugar, post-lunch blood sugar, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and total cholesterol between the T2DM patients and controls (p < 0.05). Gender, BMI, LDL cholesterol, and family history were not significantly associated with T2DM (p > 0.05), although family history was closely associated with T2DM (58.4%).

Table 1.

Quantifiable characteristics of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and healthy controls.

| S. no | Characteristics | T2DM Cases (n = 250) | Healthy Controls (n = 250) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age (Years) | 41–82 (57.19 ± 8.22) | 41–60 (53.93 ± 6.32) | 0.0003 |

| 2 | Males/Females (%) | 138 (55.2%)/112 (44.8%) | 144 (57.6%)/106(42.4%) | 0.3461 |

| 3 | BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 4.1 | 25.8 ± 3.9 | 0.4306 |

| 4 | T2DM Interval | 13.1 ± 6.3 | NA | NA |

| 5 | FBS (mg/dL) | 143.61 ± 55.66 | 93.54 ± 12.13 | <0.0001 |

| 6 | PPBG (mg/dL) | 201.29 ± 25.25 | 117.29 ± 19.07 | 0.0001 |

| 7 | Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 156.42 ± 78.97 | 138.77 ± 53.69 | <0.0001 |

| 8 | Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 183.95 ± 51.54 | 175.06 ± 33.05 | <0.0001 |

| 9 | HDL-C (mg/dL) | 88.72 ± 23.1 | 82.61 ± 20.6 | =0.01 |

| 10 | LDL-C (mg/dL) | 38.76 ± 4.4 | 35.53 ± 4.1 | =0.2658 |

| 11 | Family History, n (%) | 146 (58.4%) | 138 (55.2%) | =0.3745 |

NA: Not analyzed/Not applicable.

Characteristics of PTDM study subjects

The clinical characteristics of PTDM patients are given in Table 2. In this study, 140 RT patients were selected and categorized as having PTDM or being non-PTDM, based on biochemical tests; 30% of RT recipients developed PTDM. We included the 42 patients diagnosed with PTDM in this study and excluded the 98 non-PTDM as subjects. There were 30 male subjects and 12 female subjects in the PTDM patient group; the mean age of the male and female subjects was similar, i.e., (39.39 ± 2.12) years and (40.0 1 ± 11.63) years, respectively. Of the 42 patients with PTDM, 22 (54%) received cyclosporin treatment, whereas 20 (47.6%) received tacrolimus. When we performed the t-test between PTDM and non-PTDM subjects, gender, weight, subjects with cyclosporine drugs (i.e., CsA, Tac) and along with the dosage were found statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with post-transplant diabetes mellitus and non-post-transplant diabetes mellitus subjects.

| S. no | Baseline characteristics | PTDM (n = 42) | Non-PTDM (n = 98) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Males/Females | 30/12 | 75/23 | 0.001 |

| 2 | Age: a) Males (Mean ± SD) | 39.39 ± 12.12 | 39.55 ± 10.58 | 0.27 |

| b) Females (Mean ± SD) | 40.01 ± 11.63 | 39.26 ± 10.87 | 0.58 | |

| 3 | Weight: a) Males (Mean ± SD) | 62.73 ± 15.81 | 66.03 ± 12.73 | 0.08 |

| b) Females (Mean ± SD) | 61.71 ± 16.93 | 65.49 ± 13.68 | 0.09 | |

| 4 | a) On CsA therapy | 22 | 58 | 0.01 |

| b) On Tac therapy | 20 | 40 | 0.02 | |

| 5 | a) CsA Dose (mg) | 163.88 ± 57.4 | 201.29 ± 76.86 | 0.03 |

| b) Tac Dose (mg) | 3.15 ± 1.24 | 3.11 ± 1.62 | 0.05 | |

| 6 | a) C2 levels (ng/mL) CsA | 750 ± 299.03 | 1024.8 ± 353.42 | 0.23 |

| b) Trough levels (ng/mL) Tac | 9.55 ± 3.38 | 8.0 ± 3.32 | 0.86 | |

| 7 | a) C2 levels/dose of CsA | 5.24 ± 2.59 | 5.52 ± 1.97 | 0.02 |

| b) Trough levels/dose of Tac | 3.62 ± 1.96 | 2.98 ± 1.49 | 0.02 |

T-test was performed between PTDM and non-PTDM subjects to obtain the p Values.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

The distribution of the genotype frequencies of KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 variants in case and control subjects is in accordance with the HWE. We have carried out the statistics for power analysis, and found to be 72%. The genotypic distribution of KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 variants and their allelic frequencies in all the patients (T2DM and PTDM) and controls in this study are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Genotype and allele distribution of KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 gene polymorphisms in patients with type 2 and post-transplant diabetes mellitus and in healthy controls.

| KCNQ1 (rs2283228) | T2DM N (%) |

Controls N (%) |

Odds ratioa (95% CI) | p Value | PTDM N (%) |

Non-PTDM N (%) |

Odds ratioa,b (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 250 | 250 | 42 | 98 | ||||

| AA | 205 (82%) | 231 (92.4%) | Reference | – | 20 (47.6%) | 72 (73.5%) | Reference | – |

| AC | 41 (16.4%) | 17 (6.8%) | 2.7(1.4, 4.9) | 0.0007 | 22 (52.4%) | 26 (26.5%) | 3.0(1.4, 6.4) | 0.003 |

| CC | 04 (1.6%) | 02 (0.8%) | 2.2 (0.4, 12.4) | 0.33 | 00 (00)* | 00 (00)* | 3.5 (0.06, 183.7) | 0.50 |

| AC + CC | 45 (18%) | 19 (7.6%) | 2.6 (1.5, 4.7) | 0.0004 | 22 (52.4%)* | 26 (26.5%) | 3.0(1.4, 6.3) | 0.003 |

| A | 451 (90.2%) | 479 (95.8%) | Reference | – | 62 (73.8%) | 170 (86.7%) | Reference | – |

| C |

49 (9.8%) |

21 (4.2%) |

2.4 (1.4, 4.1) |

0.0005 |

22 (26.2%) |

26 (13.3%) |

2.3 (1.2, 4.3) |

0.008 |

|

KCNJ11 (rs5210) |

T2DM N (%) |

Controls N (%) |

Odds ratioa (95% CI) |

p Value |

PTDM N (%) |

Non-PTDM N (%) |

Odds Ratiob (95% CI) |

p Value |

| N | 250 | 250 | 42 | 98 | ||||

| AA | 101 (40.4%) | 136 (54.4%) | Reference | – | 18 (42.8%) | 84 (85.7%) | Reference | – |

| AG | 109 (43.6%) | 81 (32.4%) | 1.8(1.2, 2.6) | 0.002 | 12 (28.6%) | 08 (8.2%) | 7.0 (2.5, 19.5) | 0.0001 |

| GG | 40 (16%) | 33 (13.2%) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.7) | 0.06 | 12 (28.6%) | 06 (6.1%) | 9.3 (3.0, 28.1) | 0.0001 |

| AG + GG | 149 (59.6%) | 114 (45.6%) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | 0.001 | 24 (57.2%) | 14 (14.3%) | 8.0 (3.4, 18.4) | 0.0001 |

| A | 311 (62.2%) | 353 (70.6%) | Reference | – | 48 (57.2%) | 176 (89.8%) | Reference | – |

| G | 189 (37.8%) | 147 (29.4%) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) | 0.004 | 36 (428%) | 20 (10.2%) | 6.6 (3.5, 12.4) | <0.0001 |

Crude odds ratio (95% CI).

Odds ratio (95% CI) Adjusted for Yates correction.

Association of the rs2283228 variant with T2DM and PTDM in the case–control study

In an analysis of the frequency distribution of alleles and genotypes, the C allele of the rs2283228 polymorphism showed a strong association with T2DM (AC vs. AA: OR = 2.7 [95% CI: 1.4–4.9], p = 0.0007, and C vs. A: OR = 2.4 [95% CI: 1.4–4.1], p = 0.0005). A significant difference was observed in the dominant genotype for T2DM patients vs. controls (AC + CC vs. AA: OR = 2.6 [95% CI: 1.5–4.7], p = 0.0004). We evaluated the rs2283228 polymorphism in PTDM patients vs. non-PTDM subjects (n = 98) that were not used for the T2DM patients. Significant differences were observed between the PTDM patients and non-PTDM subjects (Table 3). There was a strong association between PTDM and the polymorphism, which was similar to that between T2DM and the polymorphism (AC vs. AA: OR = 3.0 [95% CI: 1.4–6.4], p = 0.003, and C vs. A: OR = 2.3 [95% CI: 1.2–4.3], p = 0.008). In addition, the difference in the dominant genotype for PTDM patients was significantly different from that in the controls (AC + CC vs. AA: OR = 3.0 [95% CI: 1.4–6.3], p = 0.003).

Association of the rs5210 variant with T2DM and PTDM in the case–control study

The frequency distribution of genotypes and alleles of the rs5210 polymorphism, in T2DM patients vs. controls, was determined in order to examine their association with diabetes risk (Table 3). The frequencies of the AA, AG, and GG genotypes are 40.4%, 43.6%, 16% in T2DM patients and 54.4%, 32.4%, 13.2% in control subjects, respectively. These results indicate an association between the rs5210 variant and T2DM risk in the overall analysis (AG vs. AA: OR = 1.8 [95% CI: 1.2–2.6], p = 0.002). We observed a significant difference between the allele frequencies in T2DM patients and controls (G vs. A: OR = 1.4 [95% CI: 1.1–1.9], p = 0.004).

We also assessed the rs5210 variant in PTDM patients, as shown in Table 3. The genotype frequencies for AA, AG, and GG in PTDM patients vs. non-PTDM subjects are 42.8%, 28.6%, and 28.6% vs. 85.7%, 8.2% and 6.1%. The GG genotype is more prevalent in PTDM compared to T2DM patients. There are statistically significant differences between both the genotypic distribution and the allelic frequency in PTDM patients and non-PTDM subjects (AG + GG vs. AA: OR = 8.0 [95% CI: 3.4–18.4], p = 0.0001, and G vs. A: OR = 6.6 [95% CI: 3.5–12.4], p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In this case–control study, we investigated the association of KCNQ1 (rs2283228) and KCNJ11 (rs5210) gene polymorphisms with T2DM and PTDM in Asian Indians. Previous studies of the association between different KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 SNPs and T2DM were carried out in different populations.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 However, there are no previous reports of studies that have been carried out with these SNPs (i.e., rs2283228 in KCNQ1 gene and rs5210 in KCNJ11 gene) in the Asian Indian population. To the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have addressed the influence of KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 polymorphisms on the risk or pathogenesis of T2DM in Asian Indians.26, 27, 28 Additionally, we intended to investigate the association of KCNQ1 (rs2283228) and KCNJ11 (rs5210) gene polymorphisms with both T2DM and PTDM. The present study is the first to evaluate the distribution of rs2283228 and rs5210 polymorphisms in Asian Indian patients with PTDM, and we simultaneously conducted an evaluation of patients with T2DM from the same population; both groups of patients were assessed with healthy controls for T2DM subjects and non-PTDM for PTDM subjects. The results of the present study reveal that there is an association between KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 gene polymorphisms and both T2DM and PTDM in Asian Indians.

T2DM and PTDM represent different etiologies for the same complex disease, and several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that susceptibility to PTDM, like in the case of T2DM, has a genetic component. Although no systematic studies have evaluated this hypothesis, family studies suggest that instances of PTDM aggregate within families with a history of T2DM.29 PTDM is well defined, as sustained hyperglycemia developing in any patient with/without a family history of diabetes before transplantation, and meets the present diagnostic criteria from the ADA or WHO.30 Both the diseases (T2DM and PTDM) show a correlation with changes in the KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 genes. These genes are located on chromosome 11p13–p12 and 11p15.1. The KCNQ1 gene encodes the pore-forming subunit of a voltage-gated potassium channel that plays a key role in the repolarization of the cardiac-action potential as well as in the transport of water and salts in epithelial tissues.31 KCNQ1 is expressed in pancreatic β-cells, and KCNJ11 plays a strategic role in insulin secretion by glucose-stimulated pancreatic β-cells.

A meta-analysis study by Liu et al31 demonstrated a positive association between the KCNQ1 rs2283228 polymorphism and T2DM. The rs2283228 variant, previously associated with T2DM in European (Danish), but not in Chinese (Singaporean) and Arab (Tunisian) populations,21, 32, 33 was associated with T2DM in Asian Indians. The susceptibility-conferring C allele of the rs2283228 variant was associated with increased fasting glucose levels and impaired β-cell function in Asians.34 Previous studies from the Caucasian and Korean populations, has identified the positive association of the KCNQ1 gene with PTDM11, 14; the same positive association was observed with PTDM in Asian Indian transplant recipients in the present study.

Five studies have investigated the association between the rs5210 polymorphism in the KCNJ11 gene and T2DM; these studies included meta-analyses that found this association to be significantly heterogeneous (p = 0.02).35 The rs5210 polymorphism has been shown to be associated with T2DM in Finnish, Korean, and Mexican populations,22, 36, 37 and our results in Asian Indian T2DM patients are consistent with the results of these studies. There have been two studies carried out in PTDM patients in relation to the KCNJ11 gene, i.e., Tavira et al16 reported that PTDM was associated with the rs5219 polymorphism in the Caucasian Spanish population, and Kurzawski et al38 carried out an assessment of the rs5215 polymorphism in the Caucasian Polish population and reported that it was not associated with PTDM. Our study was carried out in the Asian Indian population, and we identified that the rs5210 polymorphism was associated with PDTM in a similar way as it was associated with T2DM.

Limitations of the current study include the small number of patients confirmed with PTDM (n = 42) and our selection of only one SNP from each gene. We had missed out the glucose values for PTDM and non-PTDM subjects, which could be another limitation of our study. We also did not consider the interactions between the gene and its protein, which could require further studies. We have conducted the present study with single SNPs of the KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 genes and found these to be associated with both T2DM and PTDM in Asian Indian patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we conclude that there is a significant association between the KCNQ1 and KCNJ11 genes and the risk of developing T2DM and PTDM in Asian Indians. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings in different ethnicities, together with functional studies.

Author contribution

All the authors participated in this study have been contributed towards this manuscript. KIA has obtained the patients data. KIA has performed the laboratory work. MKK has recruited the subjects. JP has helped in data analysis. HQ and RP were PI and Co-I of this project approved by ICMR (Sanction no. 5-3-8-39-2007; RHN). KIA has written, edited the draft and MKK, JP, HQ and RP has approved the final draft.

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest towards this work.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the ICMR for providing the SRF scholarship to Imran Ali Khan Mohammed. This work was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research (Sanction no. 5-3-8-39-2007; RHN).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

References

- 1.Alharbi K.K., Khan I.A., Bazzi M.D. A54T polymorphism in the fatty acid binding protein 2 studies in a Saudi population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:61. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Hooff J.P., Christiaans M.H., van Duijnhoven E.M. Evaluating mechanisms of post-transplant diabetes mellitus. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2004;19:8–12. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghisdal L., Van Laecke S., Abramowicz M.J. New-onset diabetes after renal transplantation: risk assessment and management. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:181–188. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weng S.C., Shu K.H., Tarng D.C. Gene polymorphisms are associated with posttransplantation diabetes mellitus among Taiwanese renal transplant recipients. Transpl Proc. 2012;44:667–671. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurzawski M., Dziewanowski K., Kedzierska K. Association of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene polymorphism with posttransplant diabetes mellitus in kidney transplant patients medicated with tacrolimus. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:826–833. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70595-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luan F.L., Steffick D.E., Ojo A.O. New-onset diabetes mellitus in kidney transplant recipients discharged on steroid-free immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2011;91:334–341. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318203c25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarno G., Muscogiuri G., De Rosa P. New-onset diabetes after kidney transplantation: prevalence, risk factors, and management. Transplantation. 2012;93:1189–1195. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824db97d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang E.S., Kim M.S., Kim Y.S. A polymorphism in the zinc transporter gene SLC30A8 confers resistance against posttransplantation diabetes mellitus in renal allograft recipients. Diabetes. 2008;57:1043–1047. doi: 10.2337/db07-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott L.J., Mohlke K.L., Bonnycastle L.L. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science. 2007;316:1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sladek R., Rocheleau G., Rung J. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavira B., Coto E., Diaz-Corte C. KCNQ1 gene variants and risk of new-onset diabetes in tacrolimus-treated renal-transplanted patients. Clin Transpl. 2011;25:E284–E291. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaku K. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and its treatment policy. JMAJ. 2010;53:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chon S.J., Kim S.Y., Cho N.R. Association of variants in PPARγ², IGF2BP2, and KCNQ1 with a susceptibility to gestational diabetes mellitus in a Korean population. Yonsei Med J. 2013;54:352–357. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.2.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang E.S., Kim M.S., Kim C.H. Association of common type 2 diabetes risk gene variants and posttransplantation diabetes mellitus in renal allograft recipients in Korea. Transplantation. 2009;88:693–698. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b29c41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai F.J., Yang C.F., Chen C.C. A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility variants for type 2 diabetes in Han Chinese. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavira B., Coto E., Torres A. Association between a common KCNJ11 polymorphism (rs5219) and new-onset posttransplant diabetes in patients treated with Tacrolimus. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;105:525–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes M.B., Cobas R.A. Post-transplant diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2009;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vattam K.K., Khan I.A., Movva S. IGF2 ApaI A/G polymorphism evaluated in ESRD individuals as a Biomarker to identify patients with New onset diabetes mellitus after renal transplant in Asian Indians. Open journl Neph. 2013;2:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan I.A., Movva S., Shaik N.A. Investigation of Calpain 10 (rs2975760) gene polymorphism in Asian Indians with gestational diabetes mellitus. Meta Gene. 2014;2:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan I.A., Kamineni V., Poornima S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter polymorphism studies in pregnant women. J Reproductive Health Med. 2015;1:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unoki H., Takahashi A., Kawaguchi T. SNPs in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1098–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willer C.J., Bonnycastle L.L., Conneely K.N. Screening of 134 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) previously associated with type 2 diabetes replicates association with 12 SNPs in nine genes. Diabetes. 2007;56:256–264. doi: 10.2337/db06-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herder C., Rathmann W., Strassburger K. Variants of the PPARG, IGF2BP2, CDKAL1, HHEX, and TCF7L2 genes confer risk of type 2 diabetes independently of BMI in the German KORA studies. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:722–726. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1078730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G., Xu Y., Lin Y. Association study of genetic variants of 17 diabetes-related genes/loci and cardiovascular risk and diabetic nephropathy in the Chinese She population. J Diabetes. 2013;5:136–145. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobrikova M., Javorsky M., Habalova V. Relationship of the CDKAL1 and KCNQ1 gene polymorphisms to the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in the Slovakian population. Vnitr Lek. 2011;57:155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta V., Vinay D.G., Rafiq S. Association analysis of 31 common polymorphisms with type 2 diabetes and its related traits in Indian sib pairs. Diabetologia. 2012;55:349–357. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2355-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanghera D.K., Ortega L., Han S. Impact of nine common type 2 diabetes risk polymorphisms in Asian Indian Sikhs: PPARG2 (Pro12Ala), IGF2BP2, TCF7L2 and FTO variants confer a significant risk. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Been L.F., Ralhan S., Wander G.S. Variants in KCNQ1 increase type II diabetes susceptibility in South Asians: a study of 3,310 subjects from India and the US. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams M.A., Qiu C., Dempsey J.C. Familial aggregation of type 2 diabetes and chronic hypertension in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:955–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mora P.F. Post-Transplant diabetes mellitus. Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:86–94. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J., Wang F., Wu Y. Meta-analysis of the effect of KCNQ1 gene polymorphism on the risk of type 2 diabetes. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:3557–3567. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y.Y. The KCNJ11 E23K gene polymorphism and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Chinese Han population: a meta-analysis of 6,109 subjects. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turki A., Mtiraoui N., Al-Busaidi A.S. Lack of association between genetic polymorphisms within KCNQ1 locus and type 2 diabetes in Tunisian Arabs. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan J.T., Nurbaya S., Gardner D. Genetic variation in KCNQ1 associates with fasting glucose and beta-cell function: a study of 3,734 subjects comprising three ethnicities living in Singapore. Diabetes. 2009;58:1445–1449. doi: 10.2337/db08-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin L.J., Lv Y., Huang Q.Y. Meta-analysis of association of common variants in the KCNJ11-ABCC8 region with type 2 diabetes. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:2990–3002. doi: 10.4238/2013.August.20.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koo B.K., Cho Y.M., Park B.L. Polymorphisms of KCNJ11 (Kir6.2 gene) are associated with type 2 diabetes and hypertension in the Korean population. Diabet Med. 2007;24:178–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruz M., Valladares-Salgado A., Garcia-Mena J. Candidate gene association study conditioning on individual ancestry in patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome from Mexico City. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:261–270. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurzawski M., Dziewanowski K., Lapczuk J. Analysis of common type 2 diabetes mellitus genetic risk factors in new-onset diabetes after transplantation in kidney transplant patients medicated with tacrolimus. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1587–1594. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1292-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]