Abstract

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) technology has emerged as a powerful technology for genome editing and is now widely used in basic biomedical research to explore gene function. More recently, this technology has been increasingly applied to the study or treatment of human diseases, including Barth syndrome effects on the heart, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, hemophilia, β-Thalassemia, and cystic fibrosis. CRISPR/Cas9 (CRISPR-associated protein 9) genome editing has been used to correct disease-causing DNA mutations ranging from a single base pair to large deletions in model systems ranging from cells in vitro to animals in vivo. In addition to genetic diseases, CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing has also been applied in immunology-focused applications such as the targeting of C-C chemokine receptor type 5, the programmed death 1 gene, or the creation of chimeric antigen receptors in T cells for purposes such as the treatment of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or promoting anti-tumor immunotherapy. Furthermore, this technology has been applied to the genetic manipulation of domesticated animals with the goal of producing biologic medical materials, including molecules, cells or organs, on a large scale. Finally, CRISPR/Cas9 has been teamed with induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells to perform multiple tissue engineering tasks including the creation of disease models or the preparation of donor-specific tissues for transplantation. This review will explore the ways in which the use of CRISPR/Cas9 is opening new doors to the treatment of human diseases.

Keywords: CRISPR, DNA double-stranded break, Genome editing, Human diseases, iPS cells

Introduction

In 1987, Ishino et al discovered unusual DNA repeats of unknown function in the genome of the bacteria Escherichia coli.1 Later, Mojica et al identified these same types of repeats in other microbes and termed these to be Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats or CRISPR.2, 3, 4 The CRISPR sequences were eventually found to act as an adaptive bacteria immune defense that destroyed viral pathogens by cutting the DNA of the invader with Cas nucleases.5, 6 Importantly, the Cas nucleases were made pathogen-specific by a unique property of the enzyme, which is the requirement for an RNA guide sequence that both activates the enzyme and selectively targets the nuclease to complementary DNA sequences. This unique property of the Cas nucleases have led to its application as a high-fidelity nuclease to produce DNA breaks or nicks at essentially any location desired in genomic DNA in vivo. Among the Cas nucleases, Cas9 from E. coli has become the most extensively studied and widely used. As a result of the DNA-sequence flexibility and specificity, the CRISPR/Cas9 RNA-guided DNA editing technology has been exploited in a rapidly growing number of basic science experimental studies involving mammalian and invertebrate systems.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 While CRISPR/Cas9 is widely used in basic science research, the application of this technology in translational, disease-focused research is now emerging as an area of intensive investigation. This review will provide an overview of selected current research studies and also explore some of the future directions for the application of this technology in medicine.

CRISPR/Cas9 system

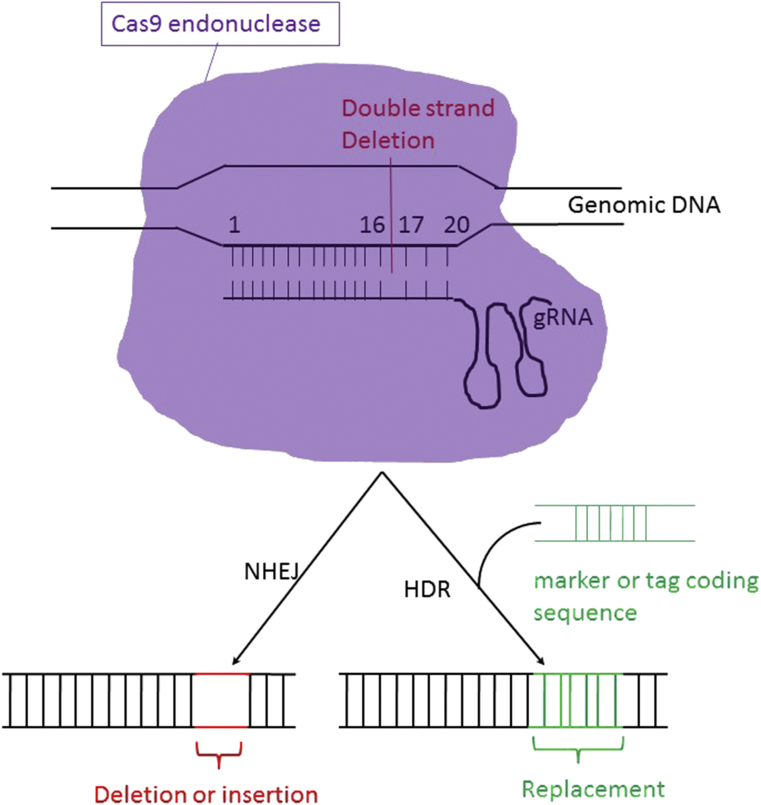

The gene editing process involves the generation of a double-stranded break (DSB) at the targeted DNA sequence. This DSB subsequently triggers two competing DNA repair systems which are homology-directed repair (HDR) or non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ, Fig. 1). NHEJ is an error-prone process in mammalian cells and can give rise to insertions or deletions (termed INDELs), either of which could change the protein coding sequences. In contrast, HDR involves homologous recombination with a donor DNA sequence to then introduce precise DNA mutations or the insertion of specific sequences in the targeted locus, such as the insertion of the DNA sequence encoding Green Fluorescence Protein (GFP).12, 13, 14, 15 The ability to use HDR to edit regions of the genome has prompted the development of multiple ways to selectively create DSBs in a sequence-specific manner. In total four major nuclease editing systems have been used to induce DSBs in the cell which include the zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), the transcription activator-like effector (TALE)-nucleases (TALENs), the meganucleases, and most recently the CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease. The application of the CRISPR/Cas9 approach only requires designing the guide RNA (gRNA) sequence complementary to any desired target region to direct the Cas9 nuclease to this site. In contrast, the ZFNs, TALENs and meganucleases systems involve a time-consuming and costly procedure to generate a new protein specific for the individual target DNA sequence. Moreover, multiplex gene alterations are only really possible with the use of CRISPR/Cas9 because multiple gRNAs can be used simultaneously.16, 17, 18

Fig. 1.

CRISPR working mechanism. Guide RNA hybridizes with 20bp genomic DNA sequence and directs Cas9 endonuclease (colored in pink) to generate a double strand break which is usually located between 16 and 17bp region in the target sequence. Subsequently, DNA Mutagenesis is generated from DNA repair process, through either the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or the homology-directed repair (HDR) mechanism. The final mutation could include insertion or deletion with several base pairs of DNA sequences (NHEJ pathway), or replacement with a particular DNA sequence used as a marker for further study (encoding for a fluorescence protein, tag protein, antibiotics, or the recognition sequence for a restriction enzyme digestion).

The specificity of the CRISPR/Cas9 system is produced by the involvement of two essential components which are the Cas9 nuclease and the required gRNA (Fig. 1). The gRNA determines the specificity for a target DNA sequence through base-pair mediated binding to complementary DNA sequences. The binding of the gRNA then co-localizes Cas9 at the same specific-site, which leads to cuts in the DNA backbone and the generation of a DSB at the site.19 Both the gRNA and Cas9 are introduced into cells by vectors created via the use of recombinant DNA technology, and depending on the application. These molecules can be expressed from either one or more different vectors.

Extensive experimental work has been used to both modify the Cas9 nuclease via the use of recombinant DNA technology or to identify Cas9 orthologues with different properties, such as changes in nuclease activity or in binding selectivity. The original form of Cas9 cleaves double-stranded DNA which triggers the DSB repair system in mammalian cells.7 In contrast, the Cas9 mutant Cas9D10A, a CRISPR Nickase, was generated by Ran et al to selectively make single strand DNA cuts at the targeted DNA sequence.20 Alternately, a nuclease-deficient Cas9, called “dead Cas9” or dCas9 was developed by Qi et al.21 The dCas9 protein has no DNA cleavage activity and has been used to create fusion proteins that target either the promoter or other regulatory sequence of a gene with the goal of altering gene expression.21, 22, 23 Furthermore, the Cas9 orthologues including CPF1 (CRISPR from Prevotella and Francisella 1),24 the high-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9,25 eSpCas9 (“enhanced specificity” Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9)26 were subsequently applied in gene editing to improve the specificity of target site and reduce the cleavage of off-target effects.

Recently, the NgAgo (Natronobacterium gregoryi Argonaute) nuclease has been utilized for gene editing, and this nuclease is able to use single-stranded DNA as the guide sequence for targeting.27 Furthermore, the NgAgo nuclease does not require a protospacer-adjacent motif sequence, which while short and common in the genome, still limits the target selection for the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

In the following sections, we summarize selected current studies using CRISPR/Cas9 as a novel therapeutic approach for human diseases utilizing both cell and animal models.

Cell models

CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been recently applied to disease-focused research through the production and characterization of patient-derived iPS cells from individuals with specific genetic diseases. The invention of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells has greatly advanced translational research, especially with the generation of disease-derived human iPS cells.28, 29 Strategies to reprogram somatic cells keep being updated, and the current methods include using four Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4),30 microRNA,31 and small molecules/chemical compounds.32, 33, 34 iPS cells have been generated and used as a “disease-in-a-dish” in vitro model for diseases including Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, and Down syndrome/trisomy 21.28, 35, 36, 37 These cells could be adapted to drug discovery, especially with the aid of high-throughput compound screening technology.28, 38, 39, 40 Additionally, enhanced DNA sequencing technologies can be used to identify the causal genetic mutation in an affected individual, and then gene editing with CRISPR/Cas9 can be used to demonstrate that the identified mutation is indeed directly responsible for disease phenotypes.

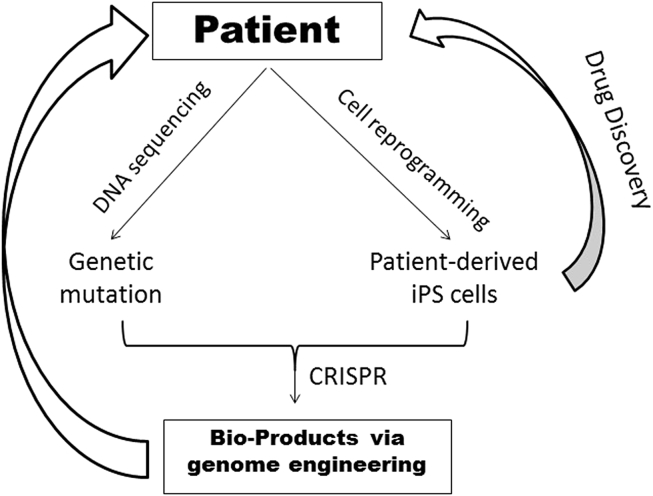

This strategy has been applied to the study of Barth syndrome, which is an X-linked genetic heart disease resulting from mutations affecting the Tafazzin gene. Tafazzin encodes a mitochondrial acyltransferase involved in the synthesis of the lipid cardiolipin, which plays critical roles in mitochondrial structure and function in the heart and other organs.41 Wang et al generated the disease-specific iPS cells from Barth syndrome patients.42 Then through a “heart-in-a-chip” model system, they discovered that genetic mutations affecting Tafazzin altered sarcomere assembly and cardiomyocyte contraction. The causal effect of these genetic mutations was also validated by creating a CRISPR engineered-Tafazzin mutation in iPS cells derived from healthy donors, which produced similar effects as those seen in the Barth syndrome-derived iPS cells. Furthermore, the iPS cells were used to test potential therapeutic agents for Barth syndrome. This pioneering study provided a framework for a “patient to patient” strategy to approach the study and potential treatment of human diseases (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CRISPR engineering for the clinics. Advances in DNA sequencing technology make it easier to identify the disease-driving genetic mutations. Meanwhile, the patient-derived iPS cells have been established to model human diseases and drug discovery in vitro. The deteriorating mutations can be corrected via the use of CRISPR-mediated gene editing, and the modified cells can be then utilized as patient-specific medicine.

An additional application of CRISPR/Cas9 modified iPS cells is through the use of tissues and organs derived from the iPS cells to provide personalized therapeutic transplants. This “patient to patient” workflow circumvents the issues of immune rejection after transplant as well as the problem of donor organ scarcity. The in vivo function of the CRISPR/Cas9-corrected iPS cells has been shown in mice with hemophilia by Park et al.43 They transplanted differentiated endothelial cells created after the correction of factor VIII deficiency through the use of CRISPR/Cas9. The ability of the modified cells to be reintroduced into mice and correct the underlying disease clearly demonstrates the potential role of CRISPR/Cas9-modified iPS cells to be a potential cure for specific types of human diseases. More studies with CRISPR-modified disease-specific iPS cells are listed in Table 1 including the application to diseases produced by single base mutations, such as Barth syndrome,42 β-Thalassemia,45, 46 and cystic fibrosis,47 and to diseases resulting from deletions of larger DNA fragments, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy48 or specific types of hemophilia.43

Table 1.

Studies using CRISPR modified disease-specific iPS cells.

| Disease | Mutation | iPS | CRISPR | Function test | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic granulomatous disease | A single intronic mutation in the CYBB gene | Skin fibroblast | CRISPR/Cas9D10A, nickase; donor-mediated HR | In vitro differentiated macrophage function | Flynn et al, 2015, Experimental Hematology44 |

| Barth syndrome | 1 bp deletion or mutation | Skin fibroblast | CRISPR/CAS9 and PiggyBac, donor-mediated HR | In vitro differentiated cardiomyocyte; muscle contraction | Wang et al, 2014, Nature Med42 |

| β-Thalassemia | C > T mutation in HBB gene | Fibroblast | CRISPR/CAS9 and PiggyBac, donor-mediated HR | In vitro hematopoietic differentiation; Gene expression | Xu et al, 2015, Sci Report45 |

| β-Thalassemia | A/G and TCTT deletion in the HBB gene | Skin fibroblast | CRISPR/CAS9 and PiggyBac, donor-mediated HR | In vitro hematopoietic differentiation; Gene expression | Xie et al, 2014, Genome Biology46 |

| Cystic fibrosis | CFTR F508 del | No iPS cells involved; 3D-intestinal organ cultures | CRISPR/CAS9, donor-mediated HR | In vitro differentiated intestinal organoids; Forskolin assay | Schwank, et al, 2013, Cell Stem Cell47 |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | 75484bp deletion including exon 44 of Dystrophin gene | Fibroblast | CRISPR/Cas9, donor-mediated HR | In vitro differentiated skeletal muscle cells; gene expression | Li et al, 2015, Stem Cell Reports48 |

| Hemophilia A | Gene inversion (140 kb and 160 kb from intron 1 to 22) | Urine cells from hemophilia A patients | Cas9 protein and gRNA DNA plasmid were delivered by a microporator system. | in vivo differentiated endothelial cells; Transplantation into a hemophilia mouse | Park et al, 2015, Cell Stem Cell43 |

CRISPR/Cas9 has also been applied to cancer immunotherapy where autologous T-cells can be engineered in vitro to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that specifically recognize cancer cells. This approach to T-cell immunotherapy has proven to be promising in treating lymphoma,49 leukemia50, 51 and melanoma in mice.52 Similarly, Programmed Death 1 (PD-1), an inhibitory receptor in T-cells has become a therapeutic target. Blockade of the interaction between PD-1 and its ligand with an anti-PD-1 antibody has been clinically tested to suppress tumors53, 54 and this treatment was approved by The Food and Drug Administration in the US to treat melanoma.53 Also the knockout of PD-1 in T cells via use of a Zinc finger nuclease55 or genome editing by CRISPR was also tested as a strategy to boost T cells activity in the setting of tumor immunotherapy.56

Finally, the editing of specific T-cell expressed genes could be used to block the continual infection of T-cells in individuals infected with HIV. Specifically, the C-C chemokine receptor type 5, also known as CCR5, acts as a co-receptor for HIV and is essential for the infection of T-cells. Clinical trials have shown that the disruption of CCR5 via Zinc-finger nuclease-mediated genome editing in HIV patients is able to block the repeated cycles of infection and permits treated individuals to clear the virus.57, 58 Thus, genome editing opens a new avenue by which to modify critical receptors or other host proteins that are essential for the pathogenesis of infectious diseases.

Animal models

To model human diseases in vivo, scientists have been using CRISPR/Cas9 to generate genome-edited animals carrying genetic mutations responsible for a number of human diseases including mouse models of tyrosinemia59 and lung cancer,60 as well as rat61 and monkey62 models of muscular dystrophy. These models are useful for investigating disease pathology or the testing of candidate treatments. However, these animals can also be used to test the ability of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to correct a disease-driving mutation in vivo. For example, Yin et al59 tested whether the hydrodynamic injection of a single stranded DNA donor plus a Cas9 expression vector and sgRNA into the tail vein could cure the fatal genetic disease, type I tyrosinemia in the mouse. Type I tyrosinemia is due to mutations in the Fah gene which encodes the metabolic enzyme fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase, and the loss of this enzyme leads to the accumulation of toxic metabolites that kill hepatocytes. The authors found that CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene editing led to expression of the wild-type Fah gene and also the survival and expansion of rescued hepatocytes. Importantly, the gene editing did not occur in all hepatocytes but instead the randomly edited hepatocytes were able to survive, grow, and then repopulate the liver. Hence, this study took advantage of a form of positive selection provided by successful gene editing, and may offer a new concept to effectively use this technology in vivo.

The CRISPR/Cas9 approach could also be potentially applied to the in vivo treatment of other genetic diseases. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a fatal genetic muscle disease, is produced by in-frame deletions affecting the dystrophin gene.63 Research laboratories of Charles A. Gersbach (Duke University),64 Eric Olson65 (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) and Amy Wagers66 (Harvard Medical School) used an adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver the CRISPR/Cas9 editing system into the mouse with the goal of removing the deleterious DNA sequences and restoring the reading frame of Dmd gene in cardiomyocytes and muscle stem cells. This AAV-mediated CRISPR treatment was able to rescue muscle structure and function, and demonstrates the therapeutic potential of CRISPR in human diseases resulting from single-gene mutations.

In a related application of CRISPR/Cas9, the technique has been used to disrupt a crucial gene required for HIV integration into the host genome.67, 68 Specifically, the Khalili lab has delivered the CRISPR/Cas9 system via a tail-vein injection to target a HIV gene which is crucial for the integration of viral DNA into the host genome.67 These treated animals demonstrated a reduced expression of HIV gene in multiple tissue organs, implicating a reduction in viral infectivity produced by CRISPR editing in vivo.

Sources of biologic therapies

Pigs organs including the heart, cornea, liver, and kidney, could become a new source of solid organs for transplant and provide a solution to the chronic shortage of available organs.69 CRISPR makes it possible to simultaneously delete multiple genes, and this capacity sets CRISPR/Cas9 apart from other gene editing tools. The Church lab has used CRISPR/Cas9 to remove 62 retrovirus genes from the pig in order to obtain the retrovirus-free tissue organs that could be suitable for xenotransplantation.70 The resulting tissue or organ replacement could prove useful in treating human diseases. For example, Elliott et al demonstrated that encapsulated pig islet cells can restore insulin production in patients with type 1 diabetes.71 Additionally, there are other late-stage clinical trials testing the safety and effectiveness of pig to human transplants.69

CRISPR/Cas9 modified pigs have also been created to make products useful for biologic therapies. Human serum albumin (ALB) is therapeutically important for patients with liver failure and traumatic shock, however the high cost and low amounts available reduce its clinical use. As a result, transgenic pigs were developed as a source of human serum albumin, however the separation of the human albumin from the endogenous pig albumin presented a practical challenge. Zhang et al used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to replace the pig albumin gene with the human albumin cDNA.72 This created pigs that only produce recombinant human albumin, which provides a promising strategy to make other biomedical therapeutics, such as humanized polyclonal antibodies, in large domesticated animals.

Perspective

Genome editing in iPS cells or in vitro cultured cells holds great potential to treat human diseases, especially for diseases produced by single-gene mutations. Patient-derived iPS cells can be tailored via CRISPR technology, selected in vitro, and delivered back to a patient to specifically replace defective cells or tissues (Fig. 2). Additionally, the pair of CRISPR/Cas9 with tissue engineering and regenerative medicine are paving the way to develop therapeutic biomaterials with either unique functional properties or on much larger scales than previously possible. However, there are both practical and ethical issues that currently represent potential barriers to the rapid application of this technology.

Since the CRISPR/Cas9 technology involves introducing vectors encoding both the gRNA and Cas9 into cells and tissues, a safe and efficient DNA delivery system are crucial to guarantee the success of gene editing. To address this challenge, various strategies are being developed to introduce the CRISPR/Cas9 components including the direct delivery of mRNA and protein or the design of new viral vector and non-viral vectors.17, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77 Anc80, an adeno-associated virus vector provides a good example of a new delivery system for in vivo gene editing and has been tested for multiple tissue organs including liver, muscle, and retina.78 Other in vivo delivery systems such as microinjection and hydrodynamic transfection have been shown to be successful in animals. However, efficient and specific gene replacement in vivo is still challenging, and the ideal means to simultaneously deliver both CRISPR and the repair donor template into the desired tissues in the body remains to be developed.

Both critics and ethical concerns have concentrated on the application of CRISPR technology in humans.79, 80 Like the experience with stem cell research, it will take time for this novel technology to be accepted in medical practice and genuine safety and ethical issues that needs to be addressed as part of this process. To our excitement, UK parliament in 2015 approved three-parent mitochondrial therapy for women with severe mitochondrial diseases. Moreover, increasing number of CRISPR related clinical trials are being proposed worldwide.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors apologize for the omission of additional applications of CRISPR/Cas9 or citations due to space limitations. This work was supported by Grant R01 AI087645 (to H.H.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); Grants ES017761, AG044768, AG013319, and AG044271 (to A.L.F.) from the NIH as well as funds from the South Texas VA Healthcare System (ALF).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

References

- 1.Ishino Y., Shinagawa H., Makino K., Amemura M., Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(12):5429–5433. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lander E.S. The heroes of CRISPR. Cell. 2016;164(1–2):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mojica F.J., Diez-Villasenor C., Soria E., Juez G. Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of archaea, bacteria and mitochondria. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(1):244–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jansen R., Embden J.D., Gaastra W., Schouls L.M. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43(6):1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J.A., Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrangou R., Fremaux C., Deveau H. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315(5819):1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cong L., Ran F.A., Cox D. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mali P., Aach J., Stranges P.B. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K.M. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339(6121):823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedland A.E., Tzur Y.B., Esvelt K.M., Colaiacovo M.P., Church G.M., Calarco J.A. Heritable genome editing in C. elegans via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Methods. 2013;10(8):741–743. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson D.J., Ward J.D., Reiner D.J., Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin S., Staahl B.T., Alla R.K., Doudna J.A. Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. Elife. 2014;3:e04766. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irion U., Krauss J., Nusslein-Volhard C. Precise and efficient genome editing in zebrafish using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Development. 2014;141(24):4827–4830. doi: 10.1242/dev.115584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baena-Lopez L.A., Alexandre C., Mitchell A., Pasakarnis L., Vincent J.P. Accelerated homologous recombination and subsequent genome modification in Drosophila. Development. 2013;140(23):4818–4825. doi: 10.1242/dev.100933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruyama T., Dougan S.K., Truttmann M.C., Bilate A.M., Ingram J.R., Ploegh H.L. Increasing the efficiency of precise genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):538–542. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox D.B., Platt R.J., Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nat Med. 2015;21(2):121–131. doi: 10.1038/nm.3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeder M.L., Gersbach C.A. Genome-editing technologies for gene and cell therapy. Mol Ther. 2016;24(3):430–446. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sander J.D., Joung J.K. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(4):347–355. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu P.D., Lander E.S., Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157(6):1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ran F.A., Hsu P.D., Lin C.Y. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154(6):1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi L.S., Larson M.H., Gilbert L.A. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152(5):1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson M.H., Gilbert L.A., Wang X., Lim W.A., Weissman J.S., Qi L.S. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(11):2180–2196. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert L.A., Larson M.H., Morsut L. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154(2):442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zetsche B., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163(3):759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinstiver B.P., Pattanayak V., Prew M.S. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016;529(7587):490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature16526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slaymaker I.M., Gao L., Zetsche B., Scott D.A., Yan W.X., Zhang F. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science. 2016;351(6268):84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao F., Shen X.Z., Jiang F., Wu Y., Han C. DNA-guided genome editing using the Natronobacterium gregoryi Argonaute. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(7):768–773. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park I.H., Arora N., Huo H. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134(5):877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merkle F.T., Eggan K. Modeling human disease with pluripotent stem cells: from genome association to function. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(6):656–668. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anokye-Danso F., Trivedi C.M., Juhr D. Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(4):376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu S., Li W., Zhou H. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Y., Desponts C., Do J.T., Hahm H.S., Scholer H.R., Ding S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small-molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(5):568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou P., Li Y., Zhang X. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341(6146):651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soldner F., Hockemeyer D., Beard C. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136(5):964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebert A.D., Yu J., Rose F.F., Jr. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457(7227):277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimos J.T., Rodolfa K.T., Niakan K.K. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321(5893):1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampaziotis F., Cardoso de Brito M., Madrigal P. Cholangiocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for disease modeling and drug validation. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(8):845–852. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juopperi T.A., Song H., Ming G.L. Modeling neurological diseases using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Future Neurol. 2011;6(3):363–373. doi: 10.2217/FNL.11.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freude K., Pires C., Hyttel P., Hall V.J. Induced pluripotent stem cells derived from Alzheimer's disease patients: the promise, the hope and the path ahead. J Clin Med. 2014;3(4):1402–1436. doi: 10.3390/jcm3041402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saric A., Andreau K., Armand A.S., Moller I.M., Petit P.X. Barth syndrome: from mitochondrial dysfunctions associated with aberrant production of reactive oxygen species to pluripotent stem cell studies. Front Genet. 2015;6:359. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang G., McCain M.L., Yang L. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat Med. 2014;20(6):616–623. doi: 10.1038/nm.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park C.Y., Kim D.H., Son J.S. Functional correction of large factor VIII gene chromosomal inversions in hemophilia a patient-derived iPSCs using CRISPR-Cas9. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(2):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flynn R., Grundmann A., Renz P. CRISPR-mediated genotypic and phenotypic correction of a chronic granulomatous disease mutation in human iPS cells. Exp Hematol. 2015;43(10) doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.06.002. 838–848 e833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu P., Tong Y., Liu X.Z. Both TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 directly target the HBB IVS2-654 (C > T) mutation in beta-thalassemia-derived iPSCs. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12065. doi: 10.1038/srep12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie F., Ye L., Chang J.C. Seamless gene correction of beta-thalassemia mutations in patient-specific iPSCs using CRISPR/Cas9 and piggyBac. Genome Res. 2014;24(9):1526–1533. doi: 10.1101/gr.173427.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwank G., Koo B.K., Sasselli V. Functional repair of CFTR by CRISPR/Cas9 in intestinal stem cell organoids of cystic fibrosis patients. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(6):653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li H.L., Fujimoto N., Sasakawa N. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(1):143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramos C.A., Heslop H.E., Brenner M.K. CAR-T cell therapy for lymphoma. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:165–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051914-021702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee D.W., Kochenderfer J.N., Stetler-Stevenson M. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):517–528. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgan R.A., Chinnasamy N., Abate-Daga D. Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J Immunother. 2013;36(2):133–151. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182829903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Topalian S.L., Hodi F.S., Brahmer J.R. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brahmer J.R., Drake C.G., Wollner I. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beane J.D., Lee G., Zheng Z. Clinical scale zinc finger nuclease-mediated gene editing of PD-1 in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Mol Ther. 2015;23(8):1380–1390. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schumann K., Lin S., Boyer E. Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):10437–10442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512503112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tebas P., Stein D., Tang W.W. Gene editing of CCR5 in autologous CD4 T cells of persons infected with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(10):901–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu W.G. Genome editing-based HIV therapies. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33(3):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yin H., Xue W., Chen S. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(6):551–553. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen S., Sanjana N.E., Zheng K. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell. 2015;160(6):1246–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakamura K., Fujii W., Tsuboi M. Generation of muscular dystrophy model rats with a CRISPR/Cas system. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5635. doi: 10.1038/srep05635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Y., Zheng Y., Kang Y. Functional disruption of the dystrophin gene in rhesus monkey using CRISPR/Cas9. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(13):3764–3774. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.England S.B., Nicholson L.V., Johnson M.A. Very mild muscular dystrophy associated with the deletion of 46% of dystrophin. Nature. 1990;343(6254):180–182. doi: 10.1038/343180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nelson C.E., Hakim C.H., Ousterout D.G. In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016;351(6271):403–407. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Long C., Amoasii L., Mireault A.A. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016;351(6271):400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tabebordbar M., Zhu K., Cheng J.K. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science. 2016;351(6271):407–411. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaminski R., Bella R., Yin C. Excision of HIV-1 DNA by gene editing: a proof-of-concept in vivo study. Gene Ther. 2016;23(8–9):690–695. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaminski R., Chen Y., Fischer T. Elimination of HIV-1 genomes from human T-lymphoid cells by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22555. doi: 10.1038/srep22555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reardon S. New life for pig-to-human transplants. Nature. 2015;527(7577):152–154. doi: 10.1038/527152a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang L., Guell M., Niu D. Genome-wide inactivation of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) Science. 2015;350(6264):1101–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elliott R.B., Escobar L., Tan P.L., Muzina M., Zwain S., Buchanan C. Live encapsulated porcine islets from a type 1 diabetic patient 9.5 yr after xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14(2):157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peng J., Wang Y., Jiang J. Production of human albumin in pigs through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockin of human cDNA into swine albumin locus in the zygotes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16705. doi: 10.1038/srep16705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Han X., Liu Z., Jo M.C. CRISPR-Cas9 delivery to hard-to-transfect cells via membrane deformation. Sci Adv. 2015;1(7):e1500454. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qin W., Dion S.L., Kutny P.M. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in mice by zygote electroporation of nuclease. Genetics. 2015;200(2):423–430. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng R., Peng J., Yan Y. Efficient gene editing in adult mouse livers via adenoviral delivery of CRISPR/Cas9. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(21):3954–3958. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yin K., Han T., Liu G. A geminivirus-based guide RNA delivery system for CRISPR/Cas9 mediated plant genome editing. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14926. doi: 10.1038/srep14926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yin H., Kanasty R.L., Eltoukhy A.A., Vegas A.J., Dorkin J.R., Anderson D.G. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(8):541–555. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zinn E., Pacouret S., Khaychuk V. In silico reconstruction of the viral evolutionary lineage yields a potent gene therapy vector. Cell Rep. 2015;12(6):1056–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liang P., Xu Y., Zhang X. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell. 2015;6(5):363–372. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kang X., He W., Huang Y. Introducing precise genetic modifications into human 3PN embryos by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(5):581–588. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0710-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]