Abstract

Thirty-five-year-old man, underwent renal transplantation 4 years back and was doing well. He now presented with complaints of ascites with engorged neck veins and dyspnoea on exertion for last 6 months. Examination showed elevated jugular venous pressure with two prominent descents, high pitched diastolic heart sound (pericardial knock). Echocardiography showed characteristic features of thickened pericardium, septal bounce, expiratory flow reversal in hepatic veins and phasic variation of mitral inflow, suggestive of constrictive pericarditis. The patient was started on empirical antitubercular therapy and diuretics. The patient symptomatically improved, but in view of persisting constrictive physiology he was planned for pericardiectomy.

Keywords: pericardial disease, tb and other respiratory infections, renal transplantation, tuberculosis

Background

Constrictive pericarditis is a rare complication in the postrenal transplant period. It poses a diagnostic challenge for clinicians, even in the modern era with vast diagnostic armamentarium. A careful neck and systemic examination in every patient with ascites shall prove beneficial to the clinician. Here we depict such a case and revisit the old yet important concept of ascites precox.

Case presentation

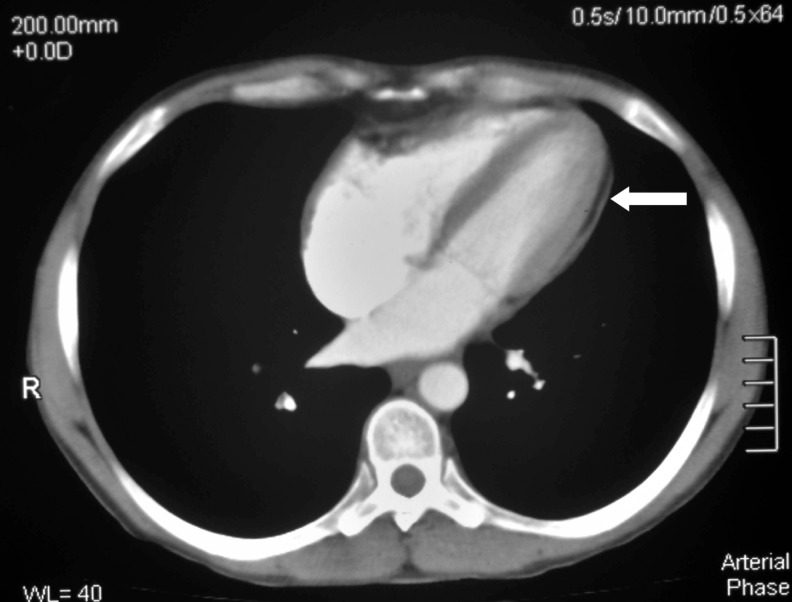

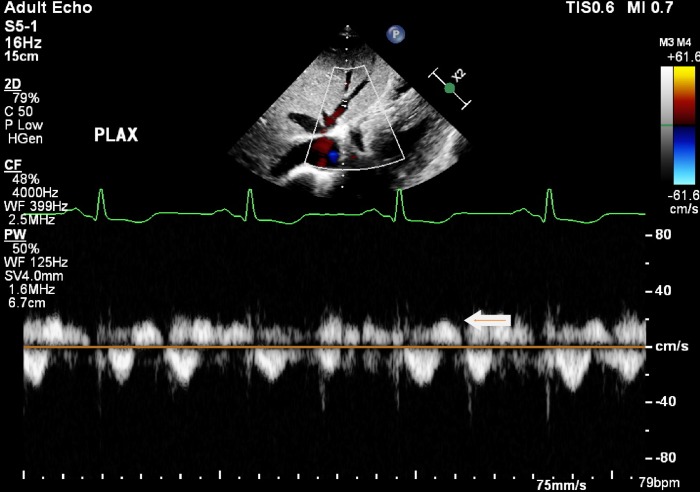

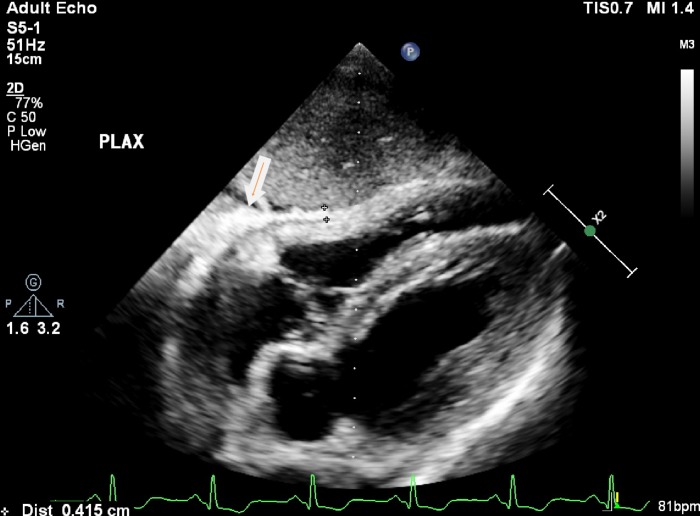

A 35-year-old male renal transplant recipient presented to our outpatient clinic with complaints of abdominal distension for the last 6 months, that was insidious in onset and gradually progressive. He had undergone a live unrelated renal transplant, with wife as donor, 4 years back. Induction agent used was antithymocyte globulin and subsequently he was on triple drug immunosuppression with tacrolimus, mycophenolate and glucocorticoids. The underlying cause for renal dysfunction was presumed to be chronic glomerulonephritis. His post-transplant baseline serum creatinine was 1.2 mg/dL. His physical examination revealed tense ascites, umbilical hernia (figure 1) and mild bilateral pitting pedal oedema. Examination of the neck showed engorged veins with elevated jugular venous pressure and rapid X and Y descents (figure 2). Cardiac auscultation revealed pericardial knock. There was no organomegaly or jaundice and rest of systemic examination was unremarkable. Ascitic fluid diagnostic analysis revealed transudative ascites with serum, ascitic albumin gradient (SAAG) of 1.4 and adenine deaminase level of 10 U/L. Other laboratory parameters revealed haemoglobin of 13 g/dL, creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL, normal liver function tests and no evidence of chronic liver disease on ultrasonography. Elevated jugular venous pressure with transudative ascites and mild peripheral oedema was suggestive of a primary cardiac constrictive–restrictive pathology. CT (figure 3) showed diffuse pericardial thickening with a maximum thickness of 6 mm and bilateral lung nodules with subcentimetric mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Echocardiogram revealed hepatic expiratory flow reversal (figure 4), diffusely thickened pericardium(figure 5) and septal bounce suggestive of constrictive pericarditis. In view of tuberculosis being the most common cause of constrictive pericarditis in the Indian subcontinent and the presence of multiple lung nodules and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, a diagnosis of chronic constrictive pericarditis (CCP) probably secondary to disseminated tuberculosis was made.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the patients abdomen showing ascites with umbilical hernia.

Figure 2.

Photograph of patients neck showing the dilated and engorged neck vein.

Figure 3.

CT of the chest showing diffuse pericardial thickening.

Figure 4.

Echocardiogram (subcostal view) showing hepatic expiratory flow reversal marked with arrow.

Figure 5.

Echocardiogram (subcostal view) showing diffusely thickened pericardium.

Outcome and follow-up

He was started on non-rifampicin-based antitubercular therapy (ATT). After 2 months of ATT and diuretics, the patient is symptomatically better and planned for pericardiectomy.

Discussion

Constrictive pericarditis develops due to inflammation followed by fibrosis and loss of normal elasticity of pericardial sac. CCP is rarely seen following renal transplantation and only few cases have been described in literature,.1–4 The rarity of the disease in this population may be due to failure to recognise the disease (transient constrictive pericarditis) or the use of immunosuppressive agents in these patients, which may reduce inflammation and hence constriction. It presents with features of right heart failure like ascites, peripheral oedema and distended neck veins. However, ascites can develop early in course of the disease (ascites pre cox) and examining neck veins in all patients with ascites may give a clue to cardiac aetiology,.5

In developing South Asian countries and regions where tuberculosis is endemic, it accounts for almost two-thirds of all cases of constrictive pericarditis and up to 50% of patients develop constrictive physiology after tuberculous pericarditis.6 7 Hence, in patients with no obvious cause for CCP, empirical antitubercular therapy may be tried. Less common causes include chest trauma, cardiac surgery, viral pericarditis, uraemia, neoplastic diseases, histoplasmosis and mediastinal irradiation.

Sever et al studied pericardial abnormalities in the first 2 months following renal transplantation and found the incidence of pericarditis to be 2.4%.8 The most common aetiology was uraemia, followed by pericarditis of unknown aetiology, cytomegalovirus infection and bacterial infections. Tuberculosis was the aetiology in one case. Incidence of constrictive pericarditis in this study was not known. In most of the case reports mentioned, constriction developed early after transplantation making uraemic or dialysis-related pericarditis as the likely aetiology. Our index case developed CCP after a long post-transplant period with good renal function narrowing our differential diagnosis to infectious/neoplastic aetiology.

In a post renal transplant patient presenting with ascites, more common causes like chronic liver disease,9 infections like peritoneal tuberculosis will be considered and may result in delay of diagnosis. So a stepwise approach should be employed to establish the diagnosis. Ascitic fluid examination provides information whether it is exudative or transudative. Exudative fluid should be further investigated for infections and neoplastic aetiology. Transudative fluid should be further characterised based on the protein content of the fluid. In patients with transudative ascites with high ascitic fluid protein content, elevated jugular venous pressure is suggestive of an underlying cardiac aetiology.

Echocardiography is invaluable for evaluating cardiac causes of ascites. It differentiates CCP from restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive cardiac failure and right heart failure which can present similarly. Findings of septal bounce, respiratory variation of blood flow across mitral and tricuspid valves and expiratory flow reversal in hepatic veins can be diagnostic and may eliminate the necessity of cardiac catherisation,.10 CT shows pericardial thickening and calcification suggestive of diagnosis of CCP in majority of cases. MR angiography also shows pericardial thickening and septal bounce s/o CCP. It also helps in differentiating from restrictive cardiomyopathy.11 In cases with doubtful diagnosis, cardiac catheterisation will establish the diagnosis.

Treatment of constrictive pericarditis consists of treating the underlying aetiology and relieving the constriction. In around 15% to 20% of patients with tubercular CCP, the constriction can be transient and resolves within 12 weeks of antitubercular therapy.12 Pericardiectomy should be considered in patients with persistent constriction. Treatment of tuberculous pericarditis consists of ATT for 6 months. Role of steroids is still debatable but recent trials showed some evidence in reduction on CCP.13 Pericardiectomy should be considered earlier, if there are features of chronic constriction like hepatic dysfunction, unresponsive ascites or pleural effusions, cachexia, calcifications or atrial fibrillation or left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Conclusion

Constrictive pericarditis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of ascites in post renal transplant patients where it is mostly attributed to chronic liver disease and peritoneal tuberculosis. Tuberculosis still remains the most common cause of CCP in endemic areas and should be carefully evaluated. Empirical therapy with antitubercular drugs may be considered in the absence of definitive evidence of tuberculosis. Further studies may help to know the incidence of tuberculosis in constrictive pericarditis and decide about empirical ATT.

Learning points.

Constrictive pericarditis is rare in post renal transplant setting and should be considered while evaluating a patient of ascites.

Multimodality imaging with echocardiography, CT and MRI helps in diagnosing CCP and may sometimes eliminate the need of invasive cardiac catheterisation.

Approximately 20% of cases of CCP maybe transient and resolve in approximately 6 months avoiding the need for pericardiectomy.

Footnotes

Contributors: GNK, DK and JS: concept and design, drafting manuscript. YPS: final editing and approval. All the authors have contributed equally and are accountable.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Celebi ZK, Keven K, Sengul S, et al. Constrictive pericarditis after renal transplantation: three case reports. Transplant Proc 2013;45:953–5. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas CK, Milligan DA, Agte SD, et al. Constrictive pericarditis following renal transplantation. J Assoc Physicians India 1982;30:251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sreejith P, Kuthe S, Jha V, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in a renal transplant recipient with tuberculosis. Indian J Nephrol 2010;20:156–8. 10.4103/0971-4065.70849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boratyńska M, Jezior D. Overlooked constrictive pericarditis as a cause of relapsing ascites and impairment of renal allograft function. Transplant Proc 2009;41:1949–50. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kothari SS, Roy A, Bahl VK. Chronic constrictive pericarditis: pending issues. Indian Heart J 2003;55:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayosi BM, Burgess LJ, Doubell AF. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation 2005;112:3608–16. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashi VV, John S, Ravikumar E, et al. Early and late results of pericardiectomy in 118 cases of constrictive pericarditis. Thorax 1988;43:637–41. 10.1136/thx.43.8.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sever MS, Steinmuller DR, Hayes JM, et al. Pericarditis following renal transplantation. Transplantation 1991;51:1229–31. 10.1097/00007890-199106000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markov M, Van Thiel DH, Nadir A. Ascites and kidney transplantation: case report and critical appraisal of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:3383–8. 10.1007/s10620-006-9727-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch TD, Ling LH, Espinosa RE, et al. Echocardiographic diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis: Mayo Clinic criteria. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:526–34. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitano G, Pressacco J, Paquet E. Imaging features of constrictive pericarditis: beyond pericardial thickening. Can Assoc Radiol J 2009;60:40–6. 10.1016/j.carj.2009.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentry J, Klein AL, Jellis CL. Transient constrictive pericarditis: current diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016;18:41 10.1007/s11886-016-0720-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Bosch J, et al. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1121–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1407380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]