Abstract

Introduction

Having many melanocytic naevi or ‘moles’ on the skin is the strongest predictor of melanoma; thus, much can be learnt from investigating naevi in the general population. We aim to improve the understanding of the epidemiology and biology of naevi by conducting a 3-year prospective study of melanocytic naevi in adults.

Methods and analysis

This is a population-based cohort study of melanocytic naevi in 200 adults aged 20–69 years recruited via the Australian electoral roll. At baseline, participants will complete a questionnaire on their sun behaviour and health and undergo a clinical examination. Three-dimensional (3D) total-body photography will be used to record the images of skin lesions. Pigmented naevi will be analysed in terms of number, diameter, colour and border irregularity using automated analysis software (excluding scalp, beneath underwear and soles of feet). All naevi ≥5 mm will be recorded using the integrated dermoscopy photographic system. A saliva sample will be obtained at baseline for genomic DNA analysis of pigmentation, naevus and melanoma-associated genes using the Illumina HumanCoreExome platform. The sun behaviour and health follow-up questionnaire, clinical examination and 3D total-body photography will be repeated every 6 months for 3 years. The first 50 participants will also undergo manual counts of naevi ≥2 mm and ≥5 mm at baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. Microbiopsy and excision of naevi of research interest is planned to commence at the 18-month time point among those who agree to donate samples for detailed histopathological and molecular assessment.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee in April 2016 (approval number: HREC/16/QPAH/125). The findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed publications and presentations at conferences.

Keywords: melanocytic naevi, moles, melanoma, skin cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Participants will be randomly selected from the general adult population.

Three-dimensional (3D) total-body photography will be conducted using state-of-the-art technology to study the natural history of naevi.

Study results will be used to establish the accuracy of 3D total-body imaging-facilitated telediagnosis and work towards decision-support systems for management of individuals at high risk of melanoma.

Limited resources prevent assessment of clinical naevus counts and clinical changes over a longer period of time.

Introduction

In 2012, melanoma accounted for 1.6% of all cancers worldwide1 and melanoma incidence and mortality continues to increase in mainly white populations.2 Early detection and prevention of melanoma are key to reducing the impact of melanoma in these populations and in this regard, much can be learnt from studying melanocytic naevi of the skin (often referred to as ‘moles’) which are the strongest known risk factors for melanoma.3 4

Melanocytic naevi are common benign neoplasms that vary from person to person and within persons in number, size, shape and colour depending on a multitude of endogenous and exogenous factors. In both adults and children, new naevi can develop and existing naevi can regress.5–7 Melanomas often grow adjacent to, or in some cases, within pre-existing naevi8 and naevi are the major differential diagnosis of primary melanoma.9 Therefore, improved understanding of naevus development and recognition of the importance of changes over time is key to understanding melanoma development and will help establish more efficient prevention and early detection models for melanoma.

Phenotypically, few differences exist between benign and early malignant melanocytic skin tumours. Biologically, naevi show certain cellular features that are also characteristics of melanomas, including an increased proliferation of cells, gain-of-function mutations in one or several primary oncogenes, avoidance or low response to tumour suppressors and evasion of apoptosis or destruction by natural killer cells.10 However, in the general population, naevi are very common and melanomas are rare and it is not yet known how the combination of dermatological features, environmental influences and genetic makeup affect the risk of developing melanoma in relation to naevi. To date, changes in naevi over time have been mostly studied in early life and longitudinal evidence on changes in naevi in adult populations, as opposed to clinical patient series, are lacking.11

This study will provide evidence regarding the macroscopic evolution of naevi by closely following adults of different ages over a 3-year period. We aim to generate new knowledge on the life cycle of naevi by age, sex and body site. Our study will combine extensive epidemiological and clinical data, various genetic analyses, and dermatological phenotyping (structural and pigmentation characteristics) of melanocytic naevi.

Methods and analysis

Study design and setting

This is a prospective population-based cohort study of the evolution of clinical features of naevi in adults living in South East Queensland. Participants will be asked to attend the research clinic at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, every 6 months for 3 years.

Study population

We will request records of 4500 people aged 20–69 years (in decades of age), residing in the greater Brisbane region from the Australian Electoral Commission (a population register, since voting is compulsory for Australian adults) and an additional 500 records of males aged 50–69 years due to their traditionally lower response rates.

Participant and public involvement

Before applying for funding, we held a forum to explore consumer priorities in regard to skin cancer prevention and experiences with sun protection and skin cancer, which helped inform the study design. We will hold biannual consumer forums to educate and inform the public of the progress of the study. Participants will also receive an annual update on the progress of the study via a newsletter.

Inclusion criteria

Participants are eligible if they are able to provide informed consent, do not have dark brown or black skin (extremely low risk of melanoma) as determined by standard questionnaire during the recruitment telephone call,12 have at least one naevus and are willing to attend the clinic for three-dimensional (3D) total-body photography every 6 months for 3 years.

Recruitment

The 5000 records received from the Australian Electoral Commission will be randomised in batches of 200 and study invitations will be mailed out in batches until our target of 200 participants is reached. The invitation will include a study information sheet, an invitation brochure with a consent-to-be-contacted form attached with three options to respond to the study invitation: reply-paid mail, text message or email.

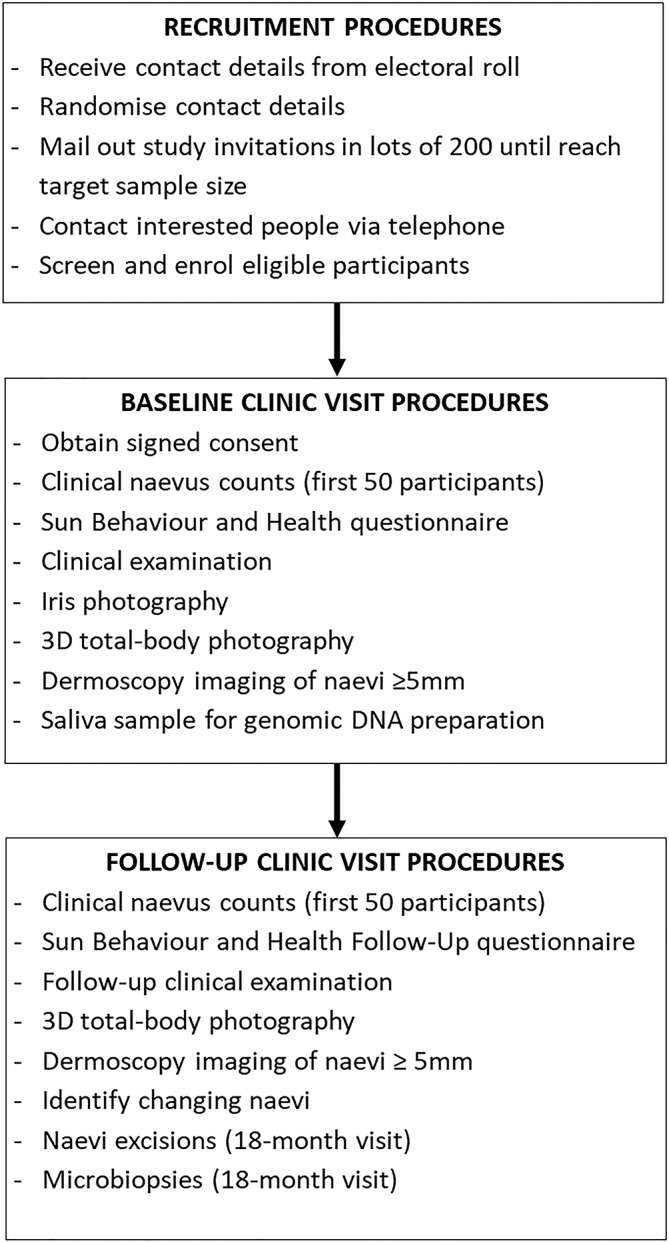

Once a completed consent-to-be-contacted form is received stating interest in the study, the project manager will telephone the person, explain study procedures and screen the respondent for eligibility (figure 1). If the respondent wishes to and is eligible to participate, a participant information and consent form (PICF) will be mailed or emailed (depending on preference) and the baseline visit scheduled. The participant will be advised to read the PICF and call our research team if they have any questions.

Figure 1.

Overview of study procedures. 3D, three-dimensional.

Baseline study procedures

Sun Behaviour and Health questionnaire

Once signed informed consent has been obtained (including consent for the donation of naevus samples, as below), a clinic staff member will administer the Sun Behaviour and Health questionnaire to gather data on personal and demographic factors, history of sun exposure, sun protection strategies, frequency of skin checks and skin cancer history. This questionnaire consists of items validated in previous studies: QSkin Study, Nambour Skin Cancer Prevention Trial, Project SCAPE, Melanoma Screening Trial and Brisbane Naevus Morphology Study.13–19

Clinical data

Dermatologically trained medical practitioners will conduct a clinical examination and record details on a standard form. Eye colour will be noted and images of both irises will be taken using a Nikon D3400 Digital Single-Lens Reflex (DSLR) camera. Freckling density on face, dorsum of right hand and shoulders will be recorded (none=1, mild=2, moderate=3, severe=4). Skin colour will be clinically assessed as being fair, medium or olive on the ventral upper arm (unexposed) and dorsal forearm (exposed). Spectrophotometry using the Thermo Fisher Scientific Spectrometer CM-600d will also be conducted to assess skin colour on three body sites: ventral upper arm at armpit, elbow and dorsal forearm. Height and weight of participants will be measured.

3D total-body photography and dermoscopy

Participants will undergo 3D total-body (excluding skin beneath underwear, scalp and soles of feet) photography using the VECTRA whole-body scanner (VECTRA WB360 Serial Number WB00009, Canfield Scientific, Parsippany, New Jersey, USA). The VECTRA whole-body scanner consists of 92 cameras with white or cross-polarised lighting, which simultaneously captures images to construct a digital 3D avatar of the participant, providing a record of all pigmented skin lesions including naevi (online supplementary files 1 and 2). Full technical details of the VECTRA are described elsewhere.20

The VECTRA scanner will be turned on and calibrated 30 min before the first imaging session of each day to ensure cameras are aligned and performing accurately. Each participant will undress to their underwear with hair tied up if applicable. Participants will be instructed on the correct stance and posture for scanning; the 3D image will then be captured in seconds and the 3D avatar constructed in approximately 10 min. Any naevus ≥5 mm will be marked by the dermatologically trained medical practitioner on the 3D avatar and non-polarised dermoscopic images of those naevi captured using the Canon EOS Rebel T6i camera and integrated into the 3D avatar by the VECTRA software.

Imaged lesions will be reviewed fortnightly by board-certified dermatologists together with dermatologically trained medical practitioners using the available clinical information, 3D avatar and dermoscopic images to identify any skin lesions suspicious for malignancy that require referral to the participant’s regular medical practitioner for management.

In the event that the VECTRA imaging system is not functioning, the participant will be rescheduled once these issues are rectified.

Clinical counts of naevi ≥2 mm and ≥5 mm

To compare naevus counts via the VECTRA automated analysis software against expert clinical counts, a dermatologist will count all naevi ≥2 mm and ≥5 mm for the first 50 participants, again excluding naevi on scalp, soles of feet and beneath underwear. The number and body site of naevi ≥2 mm and ≥5 mm will be recorded on a standard form (online supplementary file 3). As well as clinical counts of their naevi, the first 50 participants will be shown body diagrams depicting ‘few’, ‘some’ and ‘many’ moles and asked to indicate their category and the dermatologist will do the same, for later assessments of relative accuracy of estimated naevus density.

bmjopen-2018-025857supp003.pdf (457.9KB, pdf)

Saliva sample

Participants will be asked to provide a 2 mL saliva sample for genomic DNA extraction, obtained using an Oragene-DNA self-collection kit (DNA Genotek, Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Follow-up study procedures

Participants will return for follow-up every 6 months for 3 years to evaluate changes in naevi. Study procedures that will be repeated as at baseline include completion of abridged Sun Behaviour and Health questionnaire, clinical data collection, 3D total-body photography and dermoscopic imaging of naevi ≥5 mm. Any changes in skin cancer history, medical history and medications will be recorded. Clinical naevus counts will be repeated at the 6-month and 12 month follow-ups for the first 50 participants.

VECTRA Feedback questionnaire

At the 18-month follow-up visit, participant feedback on the VECTRA 3D total-body photography will be obtained using the VECTRA Feedback questionnaire. This survey consists of eight items on participant’s views about the advantages and disadvantages and their experiences with the VECTRA 3D total-body photography, as well as their level of trust and comfort with the VECTRA imaging process. We designed this questionnaire based on an adapted questionnaire for consumer mobile teledermoscopy developed from the modified technology acceptance model.21 22

Naevus microbiopsies and excisions

Depending on available funding, microbiopsies and excisions of naevi of research interest to the dermatologists will commence at the 18-month time point among those who agreed to donate naevus samples. First, the naevus for sampling will be identified, measured and photographed (clinical and dermoscopic images) and then will undergo microbiopsy in vivo to obtain 1000–3000 cells.23 24 The naevus will then undergo a shave excision with 2 mm margins: half of the lesion will be sent for routine pathology examination and the other half will be separated into lesion and perilesional sections and transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube containing 500 µL of RNALater solution,25 26 which will be stored in an 80°C freezer for later genomic DNA and/or total RNA extraction.

Participant reimbursement

At the end of each study visit, participants will receive AUD$20 in cash to assist with the transport costs of attending the study visit.

Standard operation procedure adherence checks

The project manager will conduct random checks monthly to ensure the standard operating procedures are followed for quality assurance.

Data storage

Data will be recorded on the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system, a secure study database software built by Vanderbilt University and hosted by the Queensland Clinical Trials and Biostatistics Centre at the School of Population Health, University of Queensland (https://redcap.health.uq.edu.au).

All data collected from participants will remain confidential at all times. All images, questionnaires, forms, samples and genetic data will only have the participant ID number on them to protect their privacy. The participant log of these ID numbers will be password protected and will only be accessible to study investigators. All electronic study documents will be password protected and all hard-copy documents will be stored in locked cabinets within the card access only Translational Research Institute (TRI) building.

Data processing and analysis

Genomic processing and analysis

A preservative is added to the saliva sample as part of the collection procedure. The saliva sample will be processed by adding 80 µL of purifier (PY-L2P), vortexed and incubated on ice for 10 min. The sample will then be centrifuged at 13 000 revolutions per minute for 10 min. The supernatant will be transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and 100% ethanol will be added and mixed gently by inversion. The sample will be left to stand for 10 min and centrifuged at 13 000 for 10 min. The DNA pellet will be washed with 70% ethanol, left to dry at 37°C for 5–10 min and rehydrated in 400 µL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (low EDTA, 0.1 mM). The DNA will be quantified using either the Nanodrop spectrophotometer or the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer along with the Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) BR Assay kits (Thermo Scientific). The DNA will be stored at a temperature of −20°C. A minimum of 2 µg of the extracted DNA will be submitted for Illumina CoreExomev24 Chip genotyping. The genomic DNA obtained from the naevus excisions will be analysed by whole exome sequencing to examine somatic mutations present in the lesional and perilesional tissue sections.25

VECTRA automated analysis

The VECTRA automated analysis software will count the number of naevi and take a number of measurements including the longest diameter of each naevus, contrast, border asymmetry, colour asymmetry, border irregularity, colour irregularity, hue and anatomical location.

The naevi recorded at each follow-up visit will be compared against their baseline and the number of unchanged, changed, removed or new naevi will be recorded. Changes in the size, colour, shape or in their dermoscopic features of any changed naevus ≥5 mm will be noted.

Sample size

With each participant expected to have on average 30 naevi for observation, it is expected to allow description of the summary data with 95% CIs for characteristics of 30% prevalence to range between 22% and 38% for person-based, and 29% and 31% for naevus-based analyses (binomial exact calculation). Therefore, a final sample size of 150 participants at the end of the follow-up period was deemed sufficient. To account for a drop-out rate of 20%, a minimum of 188 participants will be recruited at baseline.

Statistical analysis

For the cross-sectional data, descriptive statistical analyses including counts and proportions will be used to describe the total number of naevi (≥2 mm and ≥5 mm). The average number of naevi will be analysed and summarised according to sex, age and body site. Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise dermoscopic features of naevi by body site. Depending on the distribution of the outcomes, parametric or non-parametric approaches for bivariate analyses will be considered.

To assess the unadjusted and adjusted strength of association between participants’ phenotypic or genotypic characteristics and naevi outcomes, linear, logistic, or generalised linear regression models will be fitted, depending on the distribution of the outcome variable. These models will be conducted in crude and adjusted form to ascertain the independent contribution of explanatory factors (eg, skin type) on the outcomes. Interaction terms will also be fitted where appropriate (eg, phenotype and genotype) to explain naevus counts or distributions.

At each time point, the cross-sectional analyses will be repeated, and in addition changes in numbers of naevi over time will be calculated. Changes in naevi counts will be analysed using mixed models in order to account for the repeated measures nature of the data. Additional longitudinal analysis will include spatial-temporal models to analyse changes in naevi over time, and whether these changes are associated with a naevi cluster, or a specific body site. Age, sex and suburb information are available to assess response bias effects. To further assess effects of response bias, we will compare traits including naevus counts to those of other studies from Brisbane, such as the Brisbane Naevus Morphology Study.19

Ethics and dissemination

The findings from this study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications, non-peer-reviewed media outlets and conferences.

Conclusions

This multidisciplinary collaborative study aims to examine the evolution of benign melanocytic naevi of the skin in adulthood in more detail than reported to date. We will take advantage of recent advances in medical device development, information technology, biology, genetics and behavioural science to provide new and detailed prospective data that will aid in the general understanding of naevi and ultimately melanoma: how to better diagnose it early and prevent its development.

bmjopen-2018-025857supp001.pdf (352.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025857supp002.pdf (331KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Clare Primiero, Anthony Raphael, Elsemieke Plasmeijer, Anna Finnane and Mitchell Stark, clinic staff and consumers for their valuable contributions to this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: UK, MJ, JFA, DD, SM, HS, RAS, BB-S, TP, HPS and ACG were all involved in developing the study protocol. HPS, MJ, ACG, JFA, DD, SM, HS, RAS and TP worked together on the funding proposal. DD and BB-S provided support for the development of the statistical analysis plan. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council—Centre of Research Excellence scheme (Grant number: APP1099021). HPS is also funded by the Medical Research Future Fund— Next Generation Clinical Researcher’s Program Practitioner Fellowship (APP1137127).

Competing interests: HPS is shareholder of e-derm consult GmbH and MoleMap by dermatologists. He provides teledermatology reports regularly for both companies. HPS also consults for Canfield Scientific and is an adviser of First Derm.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee on 21 April 2016 (approval number: HREC/16/QPAH/125). Ethics approval has also been obtained from the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2016000554), Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 1600000515) and QIMR Berghofer (approval number: P2271).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. . GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The Growing Burden of Invasive Melanoma: Projections of Incidence Rates and Numbers of New Cases in Six Susceptible Populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol 2016;136:1161–71. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olsen CM, Neale RE, Green AC, et al. . Independent validation of six melanoma risk prediction models. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:1377–84. 10.1038/jid.2014.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Usher-Smith JA, Emery J, Kassianos AP, et al. . Risk prediction models for melanoma: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:1450–63. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abbott NC, Pandeya N, Ong N, et al. . Changeable naevi in people at high risk for melanoma. Australas J Dermatol 2015;56:14–18. 10.1111/ajd.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menzies SW, Stevenson ML, Altamura D, et al. . Variables predicting change in benign melanocytic nevi undergoing short-term dermoscopic imaging. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:655–9. 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duffy DL, Box NF, Chen W, et al. . Interactive effects of MC1R and OCA2 on melanoma risk phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 2004;13:447–61. 10.1093/hmg/ddh043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pandeya N, Kvaskoff M, Olsen CM, et al. . Factors related to nevus-associated cutaneous melanoma: a case-case study. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:1816–24. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weatherhead SC, Haniffa M, Lawrence CM. Melanomas arising from naevi and de novo melanomas--does origin matter? Br J Dermatol 2007;156:72–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bastian BC. The molecular pathology of melanoma: an integrated taxonomy of melanocytic neoplasia. Annu Rev Pathol 2014;9:239–71. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Plasmeijer EI, Nguyen TM, Olsen CM, et al. . The natural history of common melanocytic nevi: a systematic review of longitudinal studies in the general population. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137:2017–8. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol 1988;124:869–71. 10.1001/archderm.1988.01670060015008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olsen CM, Green AC, Neale RE, et al. . Cohort profile: the QSkin Sun and Health Study. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:929–929i. 10.1093/ije/dys107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Green A, Battistutta D, Hart V, et al. . Skin cancer in a subtropical Australian population: incidence and lack of association with occupation. The Nambour Study Group. Am J Epidemiol 1996;144:1034–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glanz K, Schoenfeld ER, Steffen A. A randomized trial of tailored skin cancer prevention messages for adults: Project SCAPE. Am J Public Health 2010;100:735–41. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aitken JF, Elwood JM, Lowe JB, et al. . A randomised trial of population screening for melanoma. J Med Screen 2002;9:33–7. 10.1136/jms.9.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Youl PH, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. . Who attends skin cancer clinics within a randomized melanoma screening program? Cancer Detect Prev 2006;30:44–51. 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cust AE, Armstrong BK, Goumas C, et al. . Sunbed use during adolescence and early adulthood is associated with increased risk of early-onset melanoma. Int J Cancer 2011;128:2425–35. 10.1002/ijc.25576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laino AM, Berry EG, Jagirdar K, et al. . Iris pigmented lesions as a marker of cutaneous melanoma risk: an Australian case-control study. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:1119–27. 10.1111/bjd.16323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rayner JE, Laino AM, Nufer KL, et al. . Clinical perspective of 3d total body photography for early detection and screening of Melanoma. Front Med 2018;5:1–6. 10.3389/fmed.2018.00152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horsham C, Loescher LJ, Whiteman DC, et al. . Consumer acceptance of patient-performed mobile teledermoscopy for the early detection of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2016;175:1301–10. 10.1111/bjd.14630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Orruño E, Gagnon MP, Asua J, et al. . Evaluation of teledermatology adoption by health-care professionals using a modified Technology Acceptance Model. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:303–7. 10.1258/jtt.2011.101101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prow TW, Lin LL, Soyer HP. The opportunity for microbiopsies for skin cancer. Future Oncol 2013;9:1241–3. 10.2217/fon.13.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin LL, Prow TW, Raphael AP, et al. . Microbiopsy engineered for minimally invasive and suture-free sub-millimetre skin sampling. F1000Res 2013;2:1–15. doi:10.12688/f1000research.2-120.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stark MS, Tan JM, Tom L, et al. . Whole-Exome sequencing of acquired nevi identifies mechanisms for development and maintenance of Benign Neoplasms. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:1636–44. 10.1016/j.jid.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan JM, Tom LN, Jagirdar K, et al. . The BRAF and NRAS mutation prevalence in dermoscopic subtypes of acquired naevi reveals constitutive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway activation. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:191–7. 10.1111/bjd.15809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025857supp003.pdf (457.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025857supp001.pdf (352.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-025857supp002.pdf (331KB, pdf)