Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and the risk of cerebral palsy (CP) in children.

Data sources

We used EMBASE, PubMed and Web of Science to conduct a meta-analysis of studies published before 1 September 2017, written in English whose titles or abstracts discussed an association between BPD and CP.

Study selection

Observational studies, for example, case–control and cohort studies were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

All review stages were conducted by two reviewers independently. Data synthesis was undertaken via meta-analysis of available evidence.

Main outcomes and measures

The prevalence of developing CP was measured after exposure to BPD.

Results

Among 1234 initially identified studies, we selected those that addressed an association between BPD and CP according to our preselected inclusion criteria. Our meta-analysis included 11 studies. According to a random effect model, BPD was significantly associated with CP (ORs 2.10; 95% CI 1.57 to 2.82) in preterm infants. Factors explaining differences in the study results included study design, the definition of BPD, the time of diagnosis of CP and whether the studies adjusted for potential confounders.

Conclusion

This study suggests that BPD is a risk factor for CP. Further studies are required to confirm these results and to detect the influence of variables across studies.

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cerebral palsy, neurodevelopment, infant

Strengths and limitations of the study.

No consensus exists regarding the association between bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and cerebral palsy (CP) in children.

The clear and univocal definition of BPD may explain the differences of the results of studies which evaluated the association between BPD and CP in children.

The number of studies included is limited, and therefore, the results of the meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Observational study designs rarely can establish causality.

Introduction

Despite advances in obstetric and neonatal care, the prevalence of developing cerebral palsy (CP) was at approximately 0.2% during the past decades,1 and the aetiology of CP remains poorly understood. Evidence shows that prenatal factors, including maternal age,2 education,3 4 obesity,5–7 race,8 chorioamnionitis1 and hypertension9 contribute to CP.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) has been implicated as a potential neonatal factor of CP.10 BPD is common in preterm and low birthweight infants born at 24–26 weeks of gestation.11 The lung is in the canalicular stage from 16 to 28 weeks, and it is in the saccular stage from 28 to 36 weeks. Alveoli are not uniformly present until 36 weeks. Thus, premature birth and the initiation of pulmonary gas exchange arrest normal alveolar and distal vascular development, and subsequent BPD.11 Maternal infection, especially maternal chorioamnionitis was associated with an increased risk of BPD.12 The inconsistencies in the definition of BPD contribute to variation in incidence of BPD. BPD is a chronic lung disease developed after mechanical ventilation or oxygen inhalation usually occurring in certain premature neonates with respiratory distress syndrome. Some studies defined as oxygen dependency at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA), yet, others defined as 28 or more days duration of oxygen dependency during hospitalisation.12 CP, cognitive delay and hearing loss are important and commonly reported adverse outcomes in very premature infants.13 It is postulated that BPD can lead to neonatal brain injury and subsequent CP.14

A number of studies have assessed the relationship between BPD and CP in premature infants, the association between BPD and CP was inconsistent. Some of the studies have not examined a significant association.15 16 For example, one study defined BPD as 28 days’ duration of oxygen dependency15 and reported insignificant association between BPD and CP, additionally, another study14 evaluated the association between BPD (oxygen dependency at 36 weeks) and quadriparas and diparesis, and reported the same result. However, any other studies17 18 showed a significant association between BPD and CP. We conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the potential association between BPD and CP in preterm infants.

Methods

Retrieval of studies

The PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science databases were searched through 1 September 2017. The search of BPD was performed using the following keywords and subject terms: ‘bronchopulmonary dysplasia’, or ‘BPD*’, or ‘lung dysplasia’, or ‘Dysplasia, Bronchopulmonary’ or ‘Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia’, using ‘OR’ to link relevant text within the search field. To acquire studies related to cerebral palsy, ‘OR’ was used to associate the keywords which included ‘cerebral palsy’, ‘Crebral pals*’, ‘spastic*’, ‘quadripleg*’ and ‘CP’. We combined these terms using ‘AND’ to retrieve the studies (see online supplementary material). We restricted the search to human studies published in English. The retrieved studies were screened by reading the titles and abstracts, and two authors (XG and LY) subsequently read the full text of the remaining publications independently and then discussed disagreements to reach a consensus.

bmjopen-2017-020735supp001.pdf (72.2KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Not required, a meta-analysis.

Study selection

The study inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the study evaluated the association between BPD and the risk of CP in children, (2) the study was published in English, (3) case–control or cohort study design, (4) the study described the assessment of exposure and outcome, the relevant exposure included any type of BPD. Relevant outcome included any definition of CP. The association between exposure and outcome was reported by unadjusted and/or adjusted relative ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% CIs, unadjusted and/or adjusted ORs estimates and 95% CIs reported the studies that could have been allowed RRs/ORs to be calculated (eg, number of cases of BPD events and total number of children with CP).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a review or meta-analysis or a case report, (2) the study was not published in English, (3) the article described an animal experiment study, (4) a study with overlapping data, (5) the articles were excluded with unusable data (eg, the articles were reported with the following unusable data, neurological lesion before discharge or CP between BPD and without BPD, we cannot know the exact result of the association between CP and BPD; neurodevelopmental outcomes (neuropsychological performance, neurodevelopmental disability) including but not limited to CP).

Data extraction

The data were independently extracted from the studies by two reviewers (XG and LY) and included the name of the first author, publication year, the country of the participants, study design, sample size, gestational age and/or birth weight, following years, BPD definition, primary outcome (the association between BPD and risk of CP) and adjusted confounders.

Quality evaluation

The two reviewers (XG and LY) independently used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)19 to examine all included studies for their methodological quality. The reviewers evaluated the quality score by examining the study population, comparability and evaluation of exposure and outcome, with a maximum score of 9. The reviewers resolved disagreements in the manner previously described.

Statistical analysis

The original studies included used ORs and/or RRs and 95% CIs to assess the association between BPD and the risk of CP in children. The ORs and RRs were directly considered as ORs when the outcome was rare.1 We pooled ORs and/or RRs of each study separately using the Der Simonian-Laird formula (random-effects model).20 Statistical heterogeneity21 between the studies was assessed using the Q and I2 statistics. Values of I2 >50% and p<0.1 indicated high heterogeneity.1 We conducted a stratified analysis based on study design (case–control, cohort), BPD type (oxygen dependency at 36 weeks’ PMA, 28 days’ duration of oxygen dependency during hospitalisation, severe BPD including mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks, no definition of BPD), diagnostic criteria for CP (age <2 years, other), confounding variables (gestational age, unadjusted estimated).

We used Egger’s22 and Begg’s23 tests to assess the publication bias which was considered to be statistically significant when p<0.05. We used Stata software V.12.0 (Stata Corp) to perform the statistical tests. We performed a ‘Test of Subgroup differences’ in software such as Review Manager V.5.3 (Cochrane).

Results

Literature search

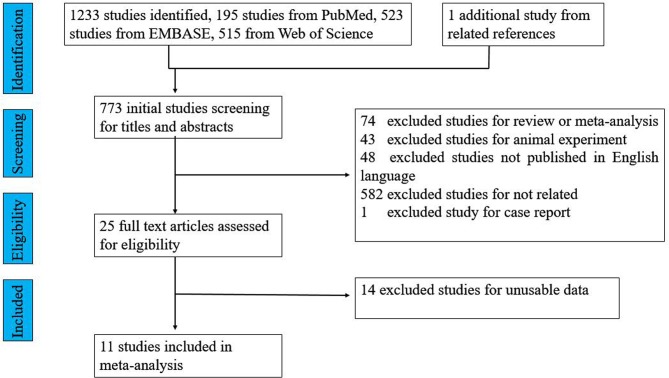

We identified 1234 potential studies: 195 from PubMed, 523 from EMBASE, 515 from Web of Science and 1 additional study from the related reference. After careful screening, 11 studies that reported the association between BPD and the risk of CP in children were selected for inclusion in this study (see figure 1). These 11 included studies are summarised in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Publication year | Country | Study design | Gestational age/BW | Sample size | BPD definition | Primary outcome | Adjusted confounder variables | NOS score |

| Gagliardi et al26 | 2009 | Italy | Cohort study | <32 weeks and BW <1500 g | 1209 | BPD (at 36 weeks’ PMA) | ORs=2.16 (CI 1.1 to 3.9) | GA, propensity score for prolonged ventilation, centre | 6 |

| Kim et al15 | 1999 | Korea | Case–control | <37 weeks | 184 | BPD (oxygen dependence at 28 days) | ORs=1.12 (CI 0.85 to 1.5) | Apgar score at 5 min, IVH, PDA, sepsis, duration of mechanical ventilation | 7 |

| Lodha et al27 | 2011 | Canada | Cohort study | <28 weeks | 918 | NA | ORs=2 (CI 1.2 to 3.2) | NA | 6 |

| Natarajan et al 25 | 2012 | NA | Cohort study | <27 weeks BW <1000 g | 1189 | BPD (at 36 weeks’ PMA) | ORs=2.41 (CI 1.4 to 4.13) | GA, male gender, SGA, maternal education, surgical NEC, IVH or PVL | 7 |

| Palta et al29 | 2000 | USA | Cohort study | BW <1500 g | 1024 | Severe BPD | ORs=2.3 (CI 1.2 to 4.6) | NA | 6 |

| Schlapbach et al18 | 2010 | Switzerland | Case–control study | <32 weeks | 99 | BPD (at 36 weeks’ PMA) | ORs=3.75 (CI 1.08 to 11.14) | Gestational age, birth weight, postnatal growth, mechanical ventilation | 7 |

| Synnes et al24 | 2017 | Canada | Cohort study | <29 weeks | 3700 | BPD (at 36 weeks’ PMA) | ORs=1.42 (CI 1.17 to 1.73) | NA | 8 |

| Tran17 | 2005 | Australia | Case–control | <27 weeks | 150 | NA home oxygen | ORs=3.4 (CI 1.2 to 9.4) | NA | 6 |

| Van Marter et al14 | 2011 | USA | Cohort study | <28 weeks | 1047 | BPD (at 36 weeks’ PMA) BPD (mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks) |

ORs=1.77 (CI 1.02 to 3.77) ORs=5.16 (CI 2.62 to 10.16) |

NA | 8 |

| Wang et al28 | 2014 | China | Cohort study | GA <30 weeks and BW <1500 g | 5807 | Not mentioned | ORs=3.14 (CI 2.61 to 3.85) | GA, BW, sex, ROP grade ≥III, grade III/IV IVH and PVL | 8 |

| Bashir et al16 | 2016 | Canada | Retrospective observational study | BW <1250 g | 1563 | BPD (at 36 weeks’ PMA) | ORs=1.3 (CI 0.87 to 1.96) | GA, male gender, ANCS use, Apgar score <7 at 5 min, SGA, postnatal steroids, blood transfusion, PDA, IVH grade ≥III and/or PVL, ROP grade ≥III and/or required laser treatment and postnatal sepsis | 8 |

ANCS, antenatal corticosteroids; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; BW, birth weight; GA, gestational age; IVH, Intraventricular hemorrhage; NA, not available; NEC, neonatal necrotising enterocolitis; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PMA, postmenstrual age; PVL, Periventricular Leukomalacia; ROP, retinopathy; SGA, small for gestational age.

Characteristics and quality of the included studies

The included studies were published between 1999 and 2017. Eleven studies evaluated the association between BPD and CP in preterm infants. Two15 16 of these studies reported no significant association. Eight of the included studies were cohort studies, and three15 17 18 of the studies were case–control studies of a high quality (NOS >5, online supplementary 2 and 3). All the studies evaluated the association between BPD and CP in preterm neonates with ORs.

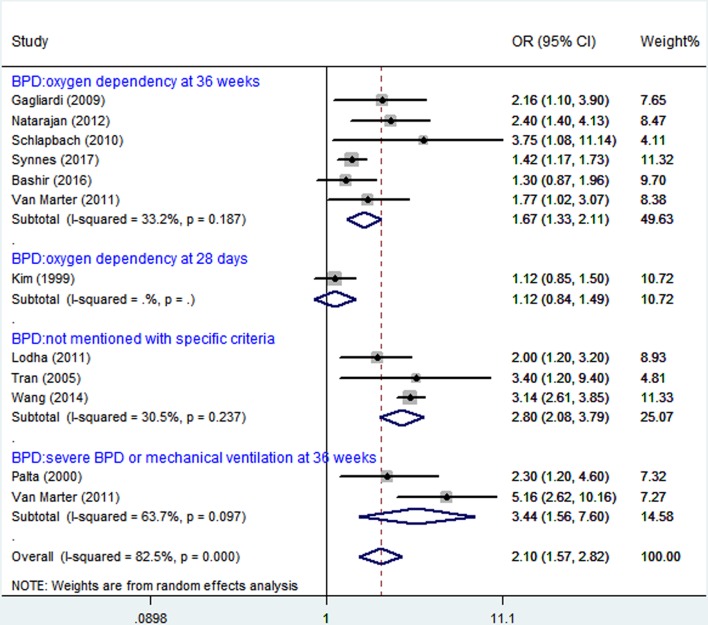

BPD and CP

When the study results were analysed using random effects model, BPD was significantly associated with CP (figure 2). These infants were preterm.

Figure 2.

Analysis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and cerebral palsy (CP).

Stratified analysis

A stratified analysis was conducted to determine whether there were any significantly different results across the subgroups considered (table 2). The case–control studies did not produce significant summary ORs (1.27; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.64, I2=72%), yet, a significant association was seen in cohort studies ORs (2.09; 95% CI 1.86 to 2.34, I2=83%). The subgroup difference was significant when stratified by study design (ORs, 1.27; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.64 vs ORs, 2.09; 95% CI 1.86 to 2.34; p<0.05, table 2).

Table 2.

Pooled results of the associations between bronchopulmonary dysplasia and cerebral palsy in children

| Variables | Studies (n) | OR (95% CI) | I2 (P values for heterogeneity) | P values |

| Total | 11 | 2.10 (1.57 to 2.82) | 82.5% (0.000) | |

| Study design | ||||

| Case–control | 3 | 1.27 (0.98 to 1.64) | 72% (0.03) | P=0.0006 |

| Cohort | 8 | 2.09 (1.86 to 2.34) | 83% (<0.00001) | |

| Definition of BPD | ||||

| Oxygen dependence at 36 weeks | 6 | 1.67 (1.33 to 2.11) | 33.2% (0.187) | P<0.00001 |

| Oxygen dependence at 28 days | 1 | 1.12 (0.84 to 1.49) | NA | |

| Severe BPD (mechanical ventilation) | 2 | 3.44 (1.56 to 7.60) | 63.7% (0.097) | |

| Not mentioned BPD type | 3 | 2.80 (2.08 to 3.79) | 30.5% (0.237) | |

| Diagnostic criteria for cerebral palsy | ||||

| Age ≥2 years only | 6 | 2.62 (2.26 to 3.05) | 71% (0.004) | P<0.00001 |

| Age <2 years included | 4 | 1.42 (1.22 to 1.64) | 64% (0.04) | |

| Controlling for potential confounders | ||||

| Unadjusted estimates | 6 | 1.48 (1.28 to 1.70) | 64% (0.02) | P<0.00001 |

| Controlled for gestational age | 5 | 2.64 (2.27 to 3.08) | 75% (0.003) | |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; NA, not available.

Six studies14 16 18 24–26 evaluated the association between BPD (oxygen dependence at 36 weeks) and CP in premature infants, with only one reporting16 no significant association (figure 2). One study15 evaluated the association between BPD (oxygen dependence at 28 days) and CP in premature infants with no significant association (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.84, 1.49). Three studies17 27 28 evaluated the association (OR 2.80, 95% CI 2.08 to 3.79, I2=30.5%) without mentioning BPD definition, and two studies14 29 showed severe BPD or mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks (OR 3.44, 95% CI 1.56 to 7.60, I2=63.7%). The subgroup difference was significant when stratified by BPD definition (p<0.00001, table 2).

The definition of CP differed greatly among studies of preterm infants (table 2). Of the four studies14 16 24 28 that provided adequate information, four studies provided a minimum age of 2 years for diagnosing CP. Some studies confirmed the diagnosis by performing examination, while others did not. Some studies excluded children with congenital anomalies,15 16 28 while others14 24 did not specify any exclusion criteria.

Five studies of BPD (PMA) in premature infants reported ORs controlled for gestational age. Association between BPD and CP remains significant both adjusted or unadjusted by gestational age (ORs 2.64; 95% CI 2.27 to 3.08 vs ORs 1.48; 95% CI 1.28 to 1.70; p<0.00001, table 2).

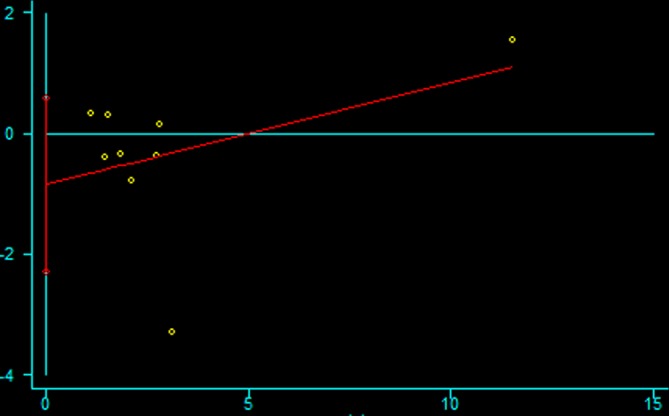

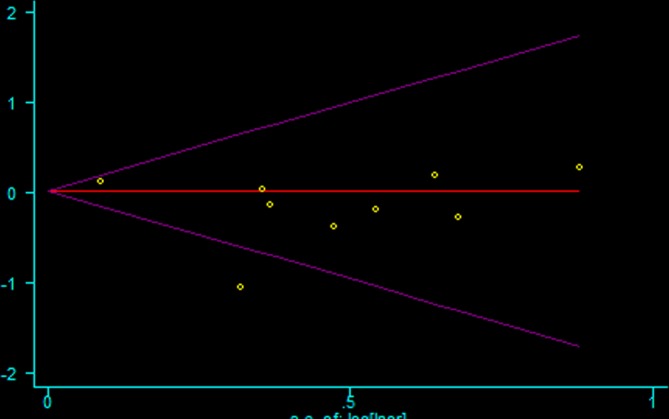

Publication bias

Asymmetry and publication bias were evaluated by Egger’s and Begg’s tests (figure 3, figure 4). The pooled results did not support the presence of significant publication bias (all p>0.05, online supplementary 4).

Figure 3.

The Egger’s test for publication bias.

Figure 4.

The Begg’s test for publication bias.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this article is the first meta-analysis of the relationship between BPD and risk of CP in children. The results of this meta-analysis, which included 11 studies, showed evidence that BPD appears to be associated with CP in preterm infants.

BPD might affect the neurodevelopmental outcome of infants through multiple pathways. A growing body of evidence supports that BPD contributes to neonatal brain injury.30 Experimental BPD with hypoxia leads to central nervous system damage, and subsequent CP.31 32 Indeed, preterm infants with BPD accompanied with hypoxia often had oligodendrocytes maturation arrest or injury,33–35 disruption of myelination and demyelination, which then caused white matter injury35 and impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes.32

To better understand the relationship between BPD and CP, it is crucial to develop consensus definitions of BPD. Most published reports do not apply specific diagnostic criteria for BPD, and as a group, these studies produced heterogeneous results. The results suggest that a stronger association is seen when used severe or mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks diagnostic criteria in the stratified analysis. The studies that do not include strict criteria may lead to an overdiagnosis of BPD which may contribute to the evidence of heterogeneity.

The definition of CP varied between studies; although CP can be difficult to diagnosis in children younger than 2 years, one study made the diagnosis in infants younger than 12 months. A consensus definition of CP is required.

Some studies report significant associations between BPD and CP after adjustments for potential confounders.15 16 18 25 26 28 Although gestational age appears to be a possible confounder, it may not lie directly in the causal pathway between BPD and CP. Gestational age can be considered as a confounder, as a premature baby is born at any gestational age and later may develop BPD. The study would falsely diminish the association between BPD and CP without considering gestational age as a confounder. BPD is associated with premature delivery and low gestational age which is associated with a host of intrinsic vulnerabilities within the brain that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of CP. Therefore, if low gestational age resulting in BPD plays a direct role in the pathogenesis of CP, then adjusting for gestational age will falsely diminish the observed association between BPD and CP. One study16 of BPD in premature infants found no association when controlling for the confounder variables, including gestational age. It is unclear if this is because BPD does not contribute independently to CP, or perhaps because gestational age lies on the causal pathway.

Other factors may interact with BPD in the pathogenetic pathway leading to CP. For example, child sex, IVH, Apgar score at 5 min, small for gestational age, which may contribute to CP, lie on the causal pathway. Accordino et al36 demonstrated that premature spontaneous birth and iatrogenic preterm birth were significantly associated with CP. The differernces of the results contribute to neurological damage would be related to infection. Although the studies controlled for some confounder variables, many other factors that contributed to CP may not be excluded.

Our meta-analysis is subject to limitations as follows. First, we only included articles published in English. Second, there may be publication bias, incomplete ascertainment of published studies and errors in data abstraction. Third, the number of studies included is small, and therefore, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the bias inherent to observational studies are not eliminated in a quantitative synthesis.

Our meta-analysis has some merits. First, the study evaluated the association between BPD and CP. Second, the study used stratified analysis to explore the heterogeneity source, and the different definition of BPD may contribute to the source of heterogeneity.

In conclusion, our pooled analyses provide evidence that BPD is significantly associated with CP in children. Future studies that consider additional factors are required to resolve this issue.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

XG and LY contributed equally.

Contributors: XG and LY contributed to the conception and design of the study, as well as to the drafting of this article. LP contributed to the collection and analysis of the data. DX contributed to the conception and design of the study and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Wu YW, Colford JM. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2000;284:1417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan C, Deroche CB, Mann JR, et al. Is prepregnancy obesity associated with risk of cerebral palsy and epilepsy in children? J Child Neurol 2014;29:Np196–201. 10.1177/0883073813510971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Villamor E, Tedroff K, Peterson M, et al. Association between maternal body mass index in early pregnancy and incidence of cerebral palsy. JAMA 2017;317:925–36. 10.1001/jama.2017.0945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Persson M, Johansson S, Villamor E, et al. Maternal overweight and obesity and risks of severe birth-asphyxia-related complications in term infants: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001648 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang Y, Tang S, Xu S, et al. Maternal body mass index and risk of autism spectrum disorders in offspring: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:34248 10.1038/srep34248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crisham Janik MD, Newman TB, Cheng YW, et al. Maternal diagnosis of obesity and risk of cerebral palsy in the child. J Pediatr 2013;163:1307–12. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forthun I, Wilcox AJ, Strandberg-Larsen K, et al. Maternal prepregnancy BMI and risk of cerebral palsy in offspring. Pediatrics 2016;138 10.1542/peds.2016-0874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bear JJ, Wu YW, Yw W. Maternal infections during pregnancy and cerebral palsy in the Child. Pediatr Neurol 2016;57:74–9. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kronenberg ME, Raz S, Sander CJ. Neurodevelopmental outcome in children born to mothers with hypertension in pregnancy: the significance of suboptimal intrauterine growth. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006;48:200–6. 10.1017/S0012162206000430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bregman J, Farrell EE. Neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin Perinatol 1992;19:673–94. 10.1016/S0095-5108(18)30451-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coalson JJ. Pathology of new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol 2003;8:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bancalari E, Claure N, Sosenko IR. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: changes in pathogenesis, epidemiology and definition. Semin Neonatol 2003;8:63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmidt B, Asztalos EV, Roberts RS, et al. Impact of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, brain injury, and severe retinopathy on the outcome of extremely low-birth-weight infants at 18 months: results from the trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms. JAMA 2003;289:1124–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Marter LJ, Kuban KC, Allred E, et al. Does bronchopulmonary dysplasia contribute to the occurrence of cerebral palsy among infants born before 28 weeks of gestation? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F20–F29. 10.1136/adc.2010.183012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim JN, Namgung R, Chang W, et al. Prospective evaluation of perinatal risk factors for cerebral palsy and delayed development in high risk infants. Yonsei Med J 1999;40:363–70. 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.4.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bashir RA, Bhandari V, Vayalthrikkovil S, et al. Chorioamnionitis at birth does not increase the risk of neurodevelopmental disability in premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Acta Paediatr 2016;105:e506–e12. 10.1111/apa.13556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tran U, Gray PH, O’Callaghan MJ. Neonatal antecedents for cerebral palsy in extremely preterm babies and interaction with maternal factors. Early Hum Dev 2005;81:555–61. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schlapbach LJ, Ersch J, Adams M, et al. Impact of chorioamnionitis and preeclampsia on neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants below 32 weeks gestational age. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:1504–9. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu T, Tang J, Zhao F, et al. Association between maternal obesity and offspring Apgar score or cord pH: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2015;5:18386 10.1038/srep18386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hartzel J, Agresti A, Caffo B. Multinomial logit random effects models. Statistical Modelling 2001;1:81–102. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Synnes A, Luu TM, Moddemann D, et al. Determinants of developmental outcomes in a very preterm Canadian cohort. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:F235–F43. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Natarajan G, Pappas A, Shankaran S, et al. Outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: impact of the physiologic definition. Early Hum Dev 2012;88:509–15. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gagliardi L, Bellù R, Zanini R, et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and brain white matter damage in the preterm infant: a complex relationship. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:582–90. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lodha A, Sauve R, Tand S, et al. Does advanced maternal age affect long term neuro developmental outcomes in preterm infants at 3 years of age? Paediatrics and Child Health 2011;16:33A. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang LW, Lin YC, Wang ST, et al. Hypoxic/ischemic and infectious events have cumulative effects on the risk of cerebral palsy in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants. Neonatology 2014;106:209–15. 10.1159/000362782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Palta M, Sadek-Badawi M, Evans M, et al. Functional assessment of a multicenter very low-birth-weight cohort at age 5 years. Newborn Lung Project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gallini F, Arena R, Stella G, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Acta Biomed 2014;85:30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doyle LW, Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Impact of postnatal systemic corticosteroids on mortality and cerebral palsy in preterm infants: effect modification by risk for chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 2005;115:655–61. 10.1542/peds.2004-1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shankaran S, Johnson Y, Langer JC, et al. Outcome of extremely-low-birth-weight infants at highest risk: gestational age < or =24 weeks, birth weight < or =750 g, and 1-minute Apgar < or =3. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:1084–91. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Back SA, Han BH, Luo NL, et al. Selective vulnerability of late oligodendrocyte progenitors to hypoxia-ischemia. J Neurosci 2002;22:455–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Back SA, Riddle A, McClure MM. Maturation-dependent vulnerability of perinatal white matter in premature birth. Stroke 2007;38(2 Suppl):724–30. 10.1161/01.STR.0000254729.27386.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Back SA, Rosenberg PA. Pathophysiology of glia in perinatal white matter injury. Glia 2014;62:1790–815. 10.1002/glia.22658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Accordino F, Consonni S, Fedeli T, et al. Risk factors for cerebral palsy in PPROM and preterm delivery with intact membranes (.). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:3854–9. 10.3109/14767058.2016.1149562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020735supp001.pdf (72.2KB, pdf)