Abstract

Objective

The Italian National Health Service instituted cervical and breast cancer screening programmes in 1999; the local health authorities have a mandate to implement these screening programmes by inviting all women aged 25–64 years for a Pap test every 3 years (or for an Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) test every 5 years) and women aged 50–69 years for a mammography every 2 years. However, the implementation of screening programmes throughout the country is still incomplete. This study aims to: (1) describe cervical and breast cancer screening uptake and (2) evaluate geographical and individual socioeconomic difference in screening uptake.

Methods

Data both from the Italian National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted by the National Institute of Statistics in 2012–2013 and from the Italian National Centre for Screening Monitoring (INCSM) were used. The NHIS interviewed a national representative random sample of 32 831 women aged 25–64 years and of 16 459 women aged 50–69 years. Logistic multilevel models were used to estimate the effect of socioeconomic variables and behavioural factors (level 1) on screening uptake. Data on screening invitation coverage at the regional level, taken from INCSM, were used as ecological (level 2) covariates.

Results

Total 3-year Pap test and 2-year mammography uptake were 62.1% and 56.4%, respectively; screening programmes accounted for 1/3 and 1/2 of total test uptake, respectively. Strong geographical differences were observed. Uptake was associated with high educational levels, healthy behaviours, being a former smoker and being Italian versus foreign national. Differences in uptake between Italian regions were mostly explained by the invitation coverage to screening programmes.

Conclusions

The uptake of both screening programmes in Italy is still under acceptable levels. Screening programme implementation has the potential to reduce the health inequalities gap between regions but only if uptake increases.

Keywords: pap test, mammography, socioeconomic, immigrants, geographic, italy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The large amount of information derived from Italian National Health Interview Survey allowed us to investigate inequities in screening uptake in Italy thoroughly for the first time.

The joint use of two data sources enabled estimating the impact of screening programmes on uptake in the country, evaluating also the differences between regions and in groups with different socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics.

It could be difficult for interviewed women to distinguish how the test was delivered (screening programme or opportunistic) and this potential recall bias could be different by citizenship or between educational levels.

The uptake obtained by the public sector, which adopts less intensive protocols and longer intervals, may be underestimated, looking at the most recent test only, because some women undergo tests at shorter intervals than recommended.

Introduction

As cervical and breast cancer screening programmes have proven effective in reducing morbidity and mortality, the European Commission recommended in 2003 that each European Union Member State offer screening to its population. In accordance with these recommendations, population-based free screening programmes, with active invitation of the target population as well as quality assurance and monitoring activities, are included in the essential healthcare services guaranteed by the Italian National Health Service (NHS). The target population for cervical screening includes all permanent and temporary (when possible) resident women aged 25–64 years, and for breast screening, women aged 50–69 years1 2; the screening tests used are a Pap test every 3 years and mammography every 2 years, in accordance with EU Recommendations (see table 1).3 4

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Italian organised screening programmes in 2013

| Cervical cancer screening | Breast cancer screening | |

| Target age | 25–64 | 50–69* |

| Test | Pap test† | Mammography (double projection) |

| Interval | 3 years | 2 years |

| Proportion of the target population regularly invited | 70.8% | 73.9% |

| Participation rate | 40.9% | 57.0% |

*In two regions, Emilia-Romagna and Piedmont, the target age was extended in 2010 to 45–74 years. In these regions, the screening interval is 1 year for women aged 45–49 years.

†Since January 2013, the Italian Ministry of Health now recommends HPV-DNA test, followed by cytology triage in case of HPV positivity, with 5-year interval, as an alternative option to Pap test every 3 years for women ≥30 years. When the interviews were conducted in 2013, only few pilot studies used HPV as primary screening test, accounting for 7.5% and 6.9% of the invited population in 2012 and 2013, respectively.

The introduction of screening programmes in Italy has been slow and characterised by profound geographical differences. The difficulties and delays in organised screening activation have favoured the spread of opportunistic screening, both by public and private providers.5 Thus, actual screening coverage and uptake are the result of both organised and opportunistic screening models.6 Organised public screening programmes include a monitoring system to determine exactly how many women are invited and screened in the target population, while opportunistic screening tests are registered in a way that does not allow a calculation of test coverage, and some are not registered at all.6 Thus, the only way to have complete information about screening coverage is by interviewing the target population. The spread of opportunistic testing and the progressive implementation of organised screening have led to a marked increase in test coverage. In 1994, the once-in-a-lifetime Pap test (ages 25–64 years) uptake was 60% and mammography (ages 50–69 years) uptake was 44%, virtually all due to opportunistic screening. In 2004, both tests had an uptake of 71%, with organised screening playing a major role, particularly for mammography.7 Nevertheless, the role of the two models in maintaining high test uptake now in Italy is unclear, and a previous project,8 based on the Green and Kreuter model9 demonstrated a negative association between organised and opportunistic screening. In the same project, factors have been classified as predisposing (scarcely or not modifiable, as age, socioeconomic status, coping and other preventive behaviours), reinforcing (eg, knowledge of the disease and of the screening effect, supporting network, ie, modifiable factors acting on the target population) and enabling factors (eg, accessibility and visibility of the screening services, ie, modifiable environmental factors). Public health interventions, both health promotion and organisation of health service, can modify the behaviours and make the environment more favourable through modification of reinforcing and enabling factors.10

In this model, organised programmes are supposed to be effect modifiers of the association between socioeconomic factors and screening participation, reducing inequalities, because the access to opportunistic screening is more probable among affluent people. In fact, organised programmes have shown to reduce inequality in access, particularly for mammography.11 Furthermore, studies on the association between healthy behaviours and screening uptake have shown inconsistent results12; the heterogeneity could be due to the different screening settings, with organised programmes showing no or small differences,13 particularly in colorectal cancer screening.14 15 In Italy, the coexistence of opportunistic and organised screening and the wide variation among regions in the level of organised screening implementation makes it possible to study how these two ways of delivering screening interact with the known determinants of screening uptake.

Study objectives are: (1) to describe cervical and breast cancer screening uptake in Italy based on data from the Italian National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted by National Institute of Statistics (Istat) in 2012–2013—we distinguish overall uptake and uptake within organised screening programmes; (2) study geographical and individual socioeconomic difference in screening uptake, and the impact of screening programme invitation coverage on these determinants.

Methods

Data sources

This study is part of epidemiological and political analyses of the barriers to implementation of and participation in screening programmes in Italy conducted within the framework of the Green and Kreuter model.9 10 16

The study was conducted based on data from the NHIS, a population-based cross-sectional survey conducted every 5 years in Italy by the Istat17 18 and from the Italian National Centre for Screening Monitoring (INCSM). The 2012–2013 edition of the NHIS collected information about screening coverage and investigated the characteristics of women who availed themselves of female cancer screening programmes, as well as other social, healthcare and behavioural covariates.

Thanks to funding from the Italian National Health Fund, the survey sample was enlarged in the 2013 survey edition, and an in-depth analysis of results from each region was performed.

It was hypothesised that total uptake is also influenced by accessible, free screening services. Thus, a variable measuring the proportion of the target population invited by the screening programme within the correct interval (the invitation coverage) at the regional level (ecological variable) was created based on data from the INCSM.12 19–21 The intervals considered were 3 years for Pap test and 2 years for mammography.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or healthy individuals were involved in this study.

Outcomes

Cervical screening uptake is defined as the percentage of women in the target age group (25–64 years) who received at least one Pap test in the 3 years prior to the interview (n=32 831, representing the population of 16 752 400 women in Italy). Breast cancer screening uptake is defined as the percentage of women in the target age group (50–69 years) who underwent at least one mammography in the 2 years prior to the interview (n=16 459, representing a population of 7 925 570 women in Italy).

Three uptake indicators were identified, based on the responses to the NHIS questionnaire: (1) total uptake, including services delivered in all types of healthcare facilities (public or private) and performed on invitation of public screening programme, on suggestion of general practitioner or private doctor or on own initiative; (2) uptake in a public healthcare facility, on the suggestion of a general practitioner or private doctor or on own initiative; (3) uptake in a public healthcare facility, on invitation to public screening programme.

Definition of individual and context factors and data analysis

A descriptive analysis evaluated the distribution of the three above-mentioned uptake indicators combined with the following fundamental dimensions: region of residence, age, citizenship, educational level, occupation, perception of economic resources, reasons hampering the pursuit of hobbies and interests (considered a proxy of availability of time), smoking habits, physical activity, weight control frequency, preventive medical examinations in the 4 weeks prior to the interview, general prevention tests (cholesterol, glycaemia, blood pressure) in the 4 weeks prior to the interview and use of complementary medicine. Regarding preventive medical examinations, we classified the variable in three categories, based on the answers to the questionnaire: (1) no examination, (2) at least one preventive examination (in the absence of disorders or symptoms), (3) examinations for other reasons (diseases or disorders, prescriptions, medical certificates, other). Hierarchical logistic models, adjusted for all the above-mentioned covariates, were tested to evaluate geographical and socioeconomic differences in Pap test and mammography uptake. The first-level unit was all target women and the second-level unit was the Italian regions (21 units). Hierarchical models were used because it can be hypothesised that Pap test and mammography uptakes have a structure of correlation between individuals that differs between regions of residence both for the effect of the heterogeneity of the public screening programme organisation and for the homogeneity in the population’s socioeconomic and demographic characteristics within each region. We estimated the geographical differences as regional residual around level 1 intercept which can be interpreted as the national mean effect after adjustment for all the covariates considered. We also calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient for the null model (without covariates) which represents the proportion of variability that can be attributed to differences between the regions. The effect of socioeconomic level was evaluated by the estimation of the ORs related to citizenship, educational level, perception of economic resources and occupation.

Having had a Pap test in the 3 years prior to the interview (2 years for mammography) was used as outcome variable based on tests performed in screening programmes and in opportunistic settings, both public and private. The above-listed categorical variables were included as first-level covariates.

Finally, in order to evaluate possible associations between the level of organised screening offered and socioeconomic access inequalities, the interaction between invitation coverage and educational level and between invitation coverage and perceived economic resources were tested. Invitation coverage was calculated as the number of invitations sent by the organised screening programme in 2011–2013 for the Pap test and in 2010–2011 for mammography divided by the total target population for each screening programme as reported by the Istat. The regional invitation coverage variable was divided into two categories based on the distribution median; Pap test cut-off was 63%, and mammography cut-off was 77%.

Results

Total Pap test uptake was slightly under two-thirds of the total target group (61.1%), 38.9% in the NHS and 22.2% in public screening programmes.

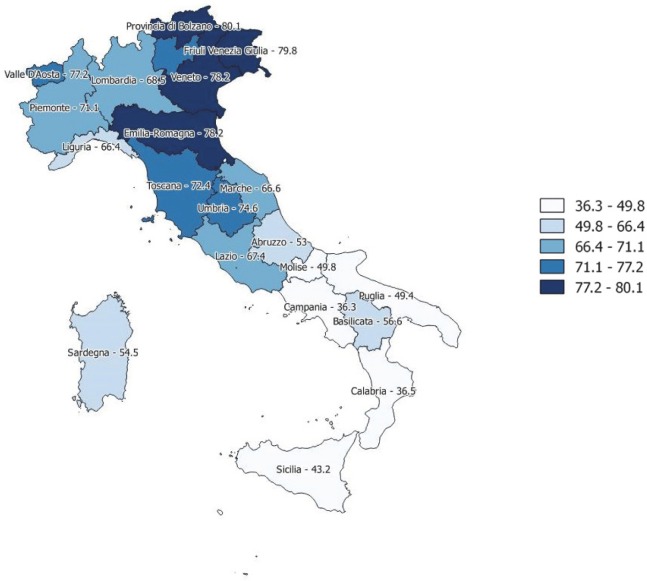

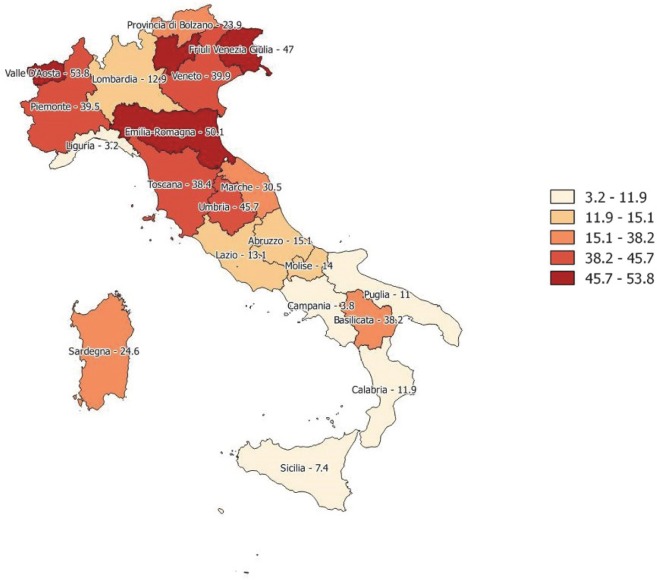

Total uptake ranged from 36.6% in Campania to 79.8% in Friuli-Venezia Giulia (figure 1), while in screening programmes it ranged from 3.2% in Liguria to 53.8% in Valle d’Aosta (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Utilisation of Pap test (*100 women in the target group). Total test uptake with the recommended schedule. Italy, 2012–2013.

Figure 2.

Utilisation of Pap test (*100 women in the target group) within organised public screening programme. Italy, 2012–2013.

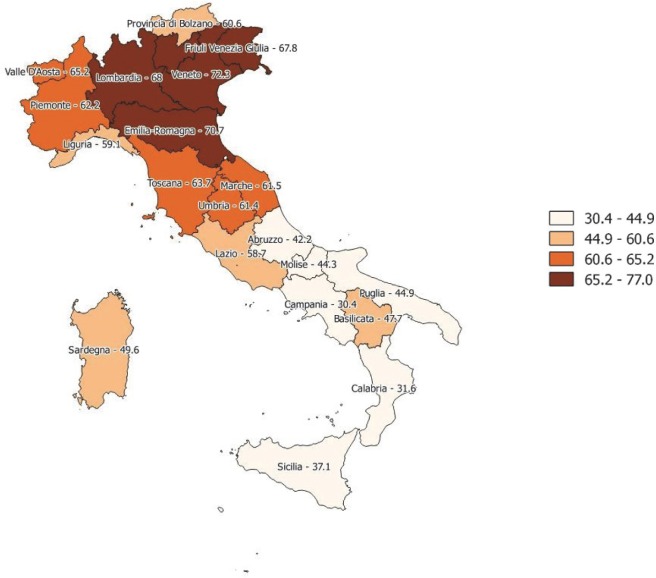

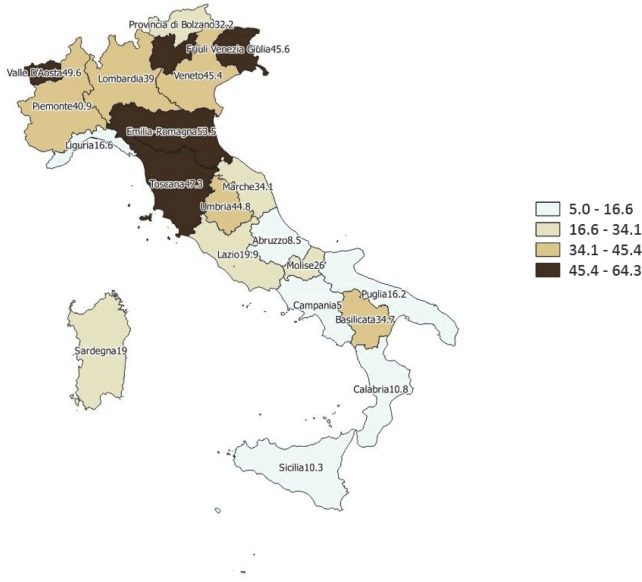

Total mammography uptake was seen in more than one-half of the target group (56.4%) and in 44.6% in the NHS, of which 29.8% were due to participation in public screening programmes.

Total uptake ranged from 30.4% in Campania to 72.3% in Veneto (figure 3), while screening programme uptake ranged from 5% in Campania to 64.3% in Trento (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Utilisation of mammography (*100 women in the target group). Total test uptake with the recommended schedule. Italy, 2012–2013.

Figure 4.

Utilisation of mammography (*100 women in the target group) within organised public screening programme. Italy, 2012–2013.

The patterns of test uptake were very similar for Pap test and mammography in almost all regions.

Total Pap test uptake increased with age up to 50 years (72.1%), and then decreased, while screening programme uptake did not decrease after age 50 (table 2).

Table 2.

Pap test and mammography: total uptake, uptake in the National Health Service and public screening coverage, by educational level, occupation and perception of economic family resources (Italy, 2012–2013)

| Pap test (n=32 831) |

Mammography (n=16 459) |

|||||

| Total uptake | Uptake in the NHS | Total uptake | Uptake in the NHS | |||

| Of which public screening coverage | Total | Of which public screening coverage | Total | |||

| Age | ||||||

| 25–29 | 48.5 | 13.3 | 28.2 | |||

| 30–34 | 58.1 | 18.6 | 35.7 | |||

| 35–39 | 63.8 | 19. 9 | 37.3 | |||

| 40–44 | 65.1 | 21.9 | 38.2 | |||

| 45–49 | 72.1 | 23.6 | 42.8 | |||

| 50–54 | 69.1 | 26.6 | 45.2 | 60.5 | 28.1 | 44.9 |

| 55–59 | 60.2 | 25.9 | 41.4 | 57.7 | 29.8 | 44.4 |

| 60–64 | 53.3 | 25.7 | 39.1 | 55.4 | 32.2 | 44.8 |

| 65–69 | 50.7 | 29.4 | 41.6 | |||

| Citizenship | ||||||

| Italian | 63.2 | 26.0 | 37.4* | 55.9 | 30.7 | 44.2 |

| Foreign national | 52.2 | 23.8 | 40.6 | 41.4 | 20.9 | 32.4 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Degree | 68.6 | 20.2 | 37.2 | 65.5 | 29.9* | 46.5 |

| School-leaving certificate | 64.6 | 21.5 | 37.4 | 60.8 | 28.8 | 44.3 |

| Compulsory education | 57.8 | 23.6 | 40.8 | 53.3 | 30.2 | 43.5 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Executive, entrepreneur, freelance professional | 74.4 | 20.1 | 35.4 | 65.1 | 27.8 | 40.9 |

| Office worker | 73.0 | 23.9 | 40.4 | 68.1 | 33.1 | 49.7 |

| Workman, apprentice, other | 64.1 | 28.2 | 45.8 | 58.2 | 34.6 | 48.6 |

| Independent businessman, homecare assistant, cooperative member | 67.5 | 24.7 | 40.2 | 60.5 | 35.7 | 50.4 |

| Contract worker | 60.2 | 20.3 | 34.4 | 59.9 | 21.3 | 40.4 |

| Not employed | 54.1 | 19.5 | 36.3 | 52.8 | 28.3 | 41.9 |

| Perceived economic resources | ||||||

| Excellent/adequate | 66.0 | 25.6 | 41.8 | 60.9 | 32.4 | 46.9 |

| Scarce/insufficient | 53.9 | 21.9 | 38.8 | 48.6 | 25.4 | 39.2 |

| Reasons hampering pursuit of hobbies or interests | ||||||

| Other | 60.3 | 22.0 | 38.7 | 55.4 | 29.5 | 43.3 |

| Too busy | 67.6 | 22.9 | 39.5 | 61.1 | 31.3 | 47.7 |

| Smoking habits | ||||||

| Smoker | 62.2 | 21.9 | 38.6 | 56.6 | 30.9 | 45.0 |

| Former smoker | 70.9 | 26.8 | 43.8 | 63.8 | 35.2 | 51.3 |

| Non-smoker | 59.6 | 21.1 | 37.6 | 53.8 | 27.7 | 41.3 |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| No | 55.9 | 19.4 | 36.2 | 47.7 | 24.0 | 37.3 |

| Yes | 67.9 | 24.8 | 41.4 | 64.9 | 35.5 | 50.6 |

| Weight control | ||||||

| Rarely or never | 56.9 | 20.7 | 36.1 | 48.7 | 25.2 | 37.7 |

| Weight controlled | 65.2 | 23.1 | 40.6 | 61.4 | 32.9 | 48.2 |

| Preventive medical examinations in the preceding 4 weeks | ||||||

| No examination | 58.0 | 20.9 | 37.0 | 52.2 | 28.2 | 41.0 |

| At least one preventive examination | 75.0 | 23.7 | 41.8 | 65.8 | 32.9 | 49.5 |

| Examinations for other reasons | 68.7 | 25.5 | 43.4 | 61.8 | 32.1 | 48.5 |

| General prevention medical tests | ||||||

| No test | 43.7 | 16.0 | 28.5 | 35.0 | 18.9 | 27.2 |

| 1 or 2 tests | 56.9 | 22.2 | 37.5 | 50.2 | 31.3 | 42.5 |

| All tests | 64.7 | 23.0 | 40.3 | 57.5 | 30.2 | 44.8 |

| Use of complementary medicine | ||||||

| Never used or more than 3 years ago | 60.0 | 21.3 | 38.2 | 54.9 | 29.1 | 43.0 |

| At least once in the last 3 years | 79.2 | 29.6 | 44.8 | 68.5 | 35.9 | 52.2 |

| Total | 62.1 | 22.2 | 38.9 | 56.4 | 29.8 | 44.0 |

*Not statistically significant.

As regards mammography, no age differences were observed in uptake between the frameworks of screening programmes and of the NHS, although total coverage uptake did decrease with age.

Total Pap test and mammography uptake were higher among Italian women than foreign nationals. This difference for Pap test was larger in opportunistic screening than in screening programmes, while for mammography, a relevant gap in uptake between Italian and foreign nationals was observed also in screening programmes (30.7% vs 20.9%).

A direct association between educational level and Pap test/mammography uptake was observed. Such an imbalance was due to lower uptake in opportunistic screening, primarily for mammography and exclusively for the Pap test.

In terms of occupation, Pap test total uptake progressively decreased from women with stronger and better paid working positions to those who lived in more unstable conditions and the unemployed. Executives, entrepreneurs, freelance professionals and office workers had higher uptake than other occupation categories, mostly due to higher uptake in private opportunistic screening. Unemployed women had low access to all screening modalities.

An association was observed between occupation and access/uptake for mammography as well, particularly for total uptake. Perceived unsatisfactory economic resources were associated with lower total uptake, lower screening programme uptake and lower NHS uptake for both Pap test and mammography. Considering indicators related to attitude towards health and prevention, higher Pap test and mammography uptake was observed in women who had other preventive health behaviours such as preventive medical examinations in the preceding 4 weeks and general prevention tests, as well as more physical activity, better weight control and being a former smoker. Also, women who used complementary medicine in the preceding 3 years had higher uptake.

Table 3 shows the results of the hierarchical logistic model for the probability of being screened for cervical cancer (ie, Pap test in the 3 years prior to the interview) expressed as OR.

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic random intercept model for having had a Pap test in the 3 years prior to interview (Italy, 2012 – 2013)

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

| Individual | ||

| Age group (years) | ||

| 25–34 | 1 | |

| 35–44 | 1.45 | 1.33 to 1.56 |

| 45–54 | 1.89 | 1.75 to 2.04 |

| 55–64 | 0.99 | 0.92 to 1.08 |

| Citizenship | ||

| Foreign national | 1 | |

| Italian | 1.69 | 1.54 to 1.85 |

| Educational level | ||

| Compulsory education | 1 | |

| School-leaving certificate | 1.12 | 1.05 to 1.19 |

| Degree | 1.16 | 1.08 to 1.27 |

| Perceived economic resources | ||

| Scarce, absolutely insufficient | 1 | |

| Excellent, adequate | 1.25 | 1.18 to 1.32 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 1 | |

| Executive, entrepreneur, freelance professional | 1.08 | 0.87 to 1.32 |

| Office worker | 1.35 | 1.16 to 1.54 |

| Workman, apprentice, other | 1.18 | 1.05 to 1.32 |

| Independent businessman, homecare assistant, cooperative member | 1.15 | 1.06 to 1.23 |

| Contract worker | 1.28 | 1.19 to 1.37 |

| Reasons hampering pursuit of hobbies or interests | ||

| Other reasons | 1 | |

| Too busy | 1.19 | 1.12 to 1.27 |

| Smoking habits | ||

| Non-smoker | 1 | |

| Former smoker | 1.37 | 1.28 to 1.45 |

| Smoker | 1.08 | 1.01 to 1.15 |

| Physical activity | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.16 | 1.10 to 1.22 |

| Weight control | ||

| Rarely or never | 1 | |

| Periodically | 1.25 | 1.19 to 1.32 |

| Preventive medical examinations in the preceding 4 weeks | ||

| No examination | 1 | |

| Other reasons | 1.43 | 1.33 to 1.52 |

| Preventive examination | 1.75 | 1.59 to 1.92 |

| General prevention medical tests | ||

| No test | 1 | |

| 1 or 2 tests | 1.41 | 1.25 to 1.61 |

| All tests | 1.85 | 1.72 to 2.00 |

| Use of complementary medicine | ||

| Never used or more than 3 years ago | 1 | |

| At least once in the last 3 years | 1.41 | 1.30 to 1.54 |

| Contextual | ||

| Invitation coverage in the period 2011–2013 | ||

| Within the median | 1 | |

| Above the median | 2.12 | 1.43 to 3.13 |

| Random effect | |||

| Estimate | SE | P values | |

| αi, regions | 0.209 | 0.066 | <0.01 |

| Intraclass correlation coefficient (ρ) |

0.06 | ||

High educational level, adequate economic conditions (OR:1.25) and especially being Italian (OR:1.69) were factors associated with higher probability for having had a Pap test. Furthermore, women who declared that they had any general prevention tests and/or medical examinations, used any complementary medicine and did any physical activity had higher probability of undergoing the Pap test in the recommended intervals. Finally, former smokers and current smokers were more likely to access cervical cancer prevention services than non-smokers.

Women living in regions with higher invitation coverage levels than the median had a higher probability of having the test than those women living in regions with lower invitation coverage levels (OR:2.12).

The effect of socioeconomic variables was similar in all the regions, regardless of invitation coverage levels.

As regards mammography, multivariate analysis (table 4) confirms the results of the bivariate analysis: women aged 60–69 years had a lower probability of having had a mammography in the years preceding the interview (OR:0.75). High educational level, adequate economic conditions (OR:1.23) and particularly being Italian (OR:2.22) were predisposing factors for accessing mammography. Furthermore, women who did any physical activity were more likely to have undergone mammography (OR:1.37). Former smokers were more likely to access breast cancer prevention compared with non-smokers. Similarly, women who had undergone general prevention tests or had a medical examination in the preceding 4 weeks for prevention or other reasons or used complementary medicine were more likely to undergo mammography. Women living in regions with high invitation coverage had a 100% higher probability of having had mammography when compared with women living in regions with low invitation coverage.

Table 4.

Multilevel logistic random intercept model for having had a mammography in the 2 yearsbefore interview (Italy, 2012 – 2013)

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

| Individual | ||

| Age group (years) | ||

| 50–59 | 1 | |

| 60–69 | 0.75 | 0.69 to 0.81 |

| Citizenship | ||

| Foreign national | 1 | |

| Italian | 2.22 | 1.85 to 2.70 |

| Educational level | ||

| Compulsory education | 1 | |

| School-leaving certificate | 1.09 | 0.99 to 1.18 |

| Degree | 1.30 | 1.14 to 1.47 |

| Perceived economic resources | ||

| Scarce, absolutely insufficient | 1 | |

| Excellent, adequate | 1.23 | 1.15 to 1.33 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 1 | |

| Executive, entrepreneur, freelance professional | 1.47 | 0.94 to 2.27 |

| Office worker | 0.99 | 0.79 to 1.25 |

| Workman, apprentice, other | 1.02 | 0.86 to 1.20 |

| Independent businessman, homecare assistant, cooperative member | 1.10 | 0.97 to 1.25 |

| Contract worker | 1.23 | 1.10 to 1.37 |

| Reasons hampering pursuit of hobbies or interests | ||

| Other reasons | 1 | |

| Too busy | 1.15 | 1.04 to 1.25 |

| Smoking habits | ||

| Non-smoker | 1 | |

| Former smoker | 1.18 | 1.09 to 1.28 |

| Smoker | 1.00 | 0.92 to 1.10 |

| Physical activity | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.37 | 1.28 to 1.47 |

| Weight control | ||

| Rarely or never | 1 | |

| Periodically | 1.33 | 1.25 to 1.43 |

| Preventive medical examinations in the last 4 weeks | ||

| No examination | 1 | |

| Other reasons | 1.52 | 1.41 to 1.64 |

| Preventive examination | 1.56 | 1.41 to 1.75 |

| General prevention medical tests | ||

| No test | 1 | |

| 1 or 2 tests | 1.43 | 1.12 to 1.82 |

| All tests | 2.00 | 1.69 to 2.38 |

| Use of complementary medicine | ||

| Never used or more than 3 years ago | 1 | |

| At least once in the last 3 years | 1.22 | 1.09 to 1.37 |

| Contextual | ||

| Invitation coverage in the period 2011 –2013 | ||

| Within the median | 1 | |

| Above the median | 2.00 | 1.43 to 2.78 |

| Random effect | |||

| Estimate | SE | P values | |

| αi, regions | 0.136 | 0.045 | <0.01 |

| Intraclass correlation coefficient (ρ) | 0.04 | ||

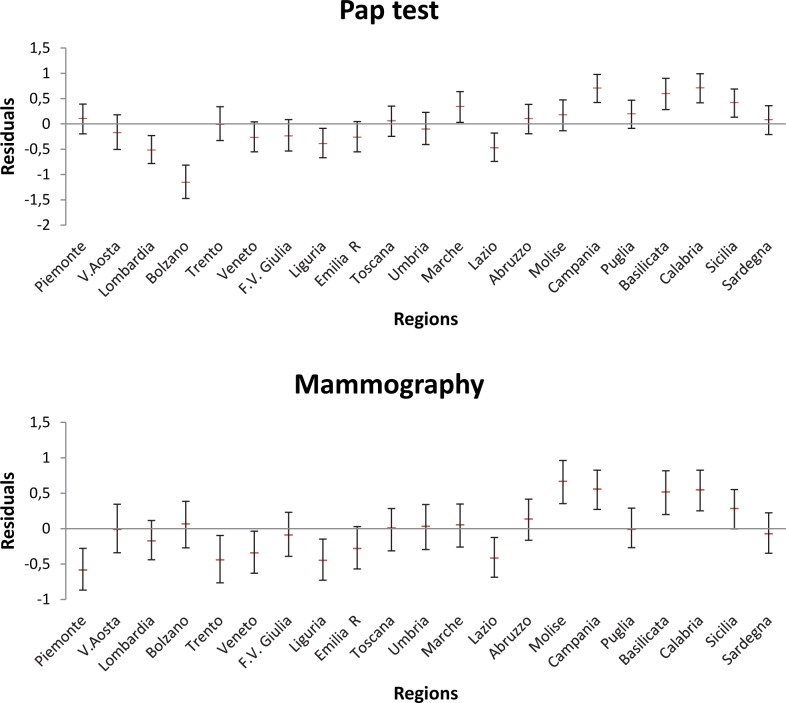

The effect of socioeconomic variables was similar in all the regions, regardless of invitation coverage levels. Residual variability around the intercept was observed for both Pap test and mammography (figure 5), with a similar geographical pattern: southern regions (except for Abruzzo, Apulia and Sardinia) showed a significantly higher probability of underuse of screening tests.

Figure 5.

Level 2 residuals of hierarchical models for Pap test and mammography. Italy, 2012–2013.

Discussion

Differences between geographical areas

Taking into account differences between the different Italian geographical areas, the observed national screening test uptake was 62.1% for cervical cancer and 56.4% for breast cancer. These values are lower than the Italian and the European guidelines reference standards for screening programmes: 70% acceptable and 85% desired for cervical cancer and 70% acceptable and 75% desired for breast.2 4 22 Strong uptake differences still exist between regions, with a clear north–south gradient.8 A positive trend is that differences between northern and southern Italy have diminished compared with the previous NHISs due to increased coverage/access in the southern regions.17 Differences between regions can be largely attributed to the NHS’s ability to offer screening programmes that reach the target population. This hypothesis is also supported by the results of multilevel models showing how variability between regions is strongly related to screening programme coverage in the single regions, particularly for mammography. This phenomenon can be observed at a macrolevel: those regions with higher uptake are also those with higher access in the frameworks of screening programmes or of the NHS. The effect on total uptake of organised screening with active invitations to the target population is well known and has been observed in all contexts.11 23 24 Finally, it is also interesting to note that total and screening programme uptake patterns are similar in almost all regions. This suggests that where the population’s attention to prevention is low, there has also been difficulty in implementing screening programmes. This result is consistent with the consolidated evidence of an association between low/changeable invitation coverage of screening programmes and low response from the population to invitations.5 6 20 21

It is not easy to understand the causal relationship; if a context is unfavourable to the organisation of complex and multidisciplinary paths, is this because the population in that context does not trust the NHS and thus does not respond to the invitation? Or is it because the poor organisation directly penalises compliance with programme recommendations?

Socioeconomic differences

Socioeconomic differences in uptake are still very evident, whichever variable is considered: education, citizenship, occupation or perceived economic difficulties. In particular, foreign women had a 40% lower uptake probability than Italians for Pap test and 55% lower probability for mammography. In Italy, immigration is a recent phenomenon, with a marked increase during the first decade of the 2000s, so it is conceivable that both cultural and language barriers may influence access to screening programmes and health services. However, a recent paper showed that screening uptake was heterogeneous by area of origin (Africans have lower Pap test and mammography uptake) and by region of residence,25 highlighting that there are margins for improving equity. Regarding education, our result confirms what has been observed in England,26 where a recent study showed a significant improvement of equitable delivery of breast screening but not of cervical screening.27 Unfortunately, our dataset did not include information on income, though we can show the effect of economic conditions indirectly through survey respondents’ perceived economic difficulties. Nevertheless, its association with uptake is more difficult to interpret, as this variable combines objective available resources and factors related to more subjective perception of precarious conditions or worsening of one’s economic situation.11 These latter factors are more related to personal coping—the ability to react to changes and difficulties, a personal characteristic known to be associated with participation in screening; ‘maladaptive coping’, instead, is associated with poor compliance with cancer screening recommendations.16 These personal characteristics are difficult to modify through active interventions such as invitation letters or information campaigns.11 28

Even though organised screening programmes and the NHS guarantee wider and easier access to screening, thus increasing coverage in all contexts, surprisingly, no reduction in socioeconomic differences was observed in the areas where screening programmes had higher invitation coverage. This effect on reducing access inequalities has been observed in other Italian studies.13 29 Furthermore, the implementation of screening programmes has shown a levelling effect on breast cancer outcomes, with women in the lowest socioeconomic level attaining the same survival rates as those in the highest socioeconomic level.30 31 A decrease in inequalities in access to effective prevention measures thanks to screening programmes and to the NHS actively promoting interventions has been observed in a number of other studies,6 11 32 33 even though considerable exceptions or failures have also been observed.34–36

Association with other preventive health behaviours

We observed associations between screening uptake and single preventive health behaviours. The existing synergy between prevention interventions and preventive health behaviours is a well-known phenomenon which offers the NHS opportunities to promote coordinated prevention initiatives.37

The association between both screening test uptake and being a former smoker is not surprising and has been reported by other authors13 38; instead, a slightly higher uptake for both Pap test and mammography in current smokers than in non-smokers is more surprising. It should be noted that, in women, the prevalence of smoking in Italy is higher among the highly educated; the difference in screening uptake thus almost disappears when adjusting for educational level. Particular attention should be paid to the association between mammography uptake and use of complementary medicine, a partially unexpected result, as breast screening has been criticised in the last few years by groups concerned with overdiagnosis and overtreatment and against the medicalisation of the healthy population.39 40 These opinions, which are not against technology per se, are welcome in cultural contexts that refuse a technological approach to life and healthcare and that are often attracted to complementary medicine.41 A positive association between complementary medicine and mammography coverage thus suggests that a lack of coverage is, to a large degree, not a conscious choice but instead due to the lack of access to the service.

Limitations and strengths of the study and comparison with other data

The main limitations of the data used in the present study are related to data-collection techniques, namely a retrospective study based on the recall of the interviewed women. When recalling past events, it can be difficult to distinguish between different organisational and administrative ways of how the test was delivered. For example, a test undergone in the framework of a screening programme could be confused with a test provided by the NHS outside an organised programme (in some local health services, the patient cannot perceive this difference). This observation does not influence total uptake but can generate incorrect classification of access modalities that can differ between Italian women and foreign nationals or between different educational levels. In fact, it can be difficult to define just what a ‘screening programme’ is, resulting in a possible misunderstanding and thus confusing it with a more general access to a public health centre, particularly by less-educated women or foreign nationals with linguistic barriers. For this reason, most of the analysis was conducted by using the two indicators ‘public sector uptake’ and ‘screening programme uptake’ to give an idea of the range of the actual data. Furthermore, some women undergo tests at shorter intervals than is recommended,6 42 which can mask part of the uptake obtained by the NHS when we look at the most recent test only, as in this survey. In fact, if a woman has already undergone a test performed in the NHS and then undergoes an opportunistic test before the recommended interval has expired, she will register as covered by the opportunistic test and not by the previous NHS test. Thus, we underestimate the coverage by the public sector, which adopts less intensive protocols and longer intervals.42 43 Furthermore, a survey with less stringent questions to identify the date of the last screening test may overestimate coverage due to telescoping effect (women reporting having undergone the test more recently than in fact they have), as noted in a previous Italian survey.43 Indeed, the questions about the last screening test are posed slightly differently in the Italian NHIS and in the routine surveillance system—the Progressi delle Aziende Sanitarie per la Salute in Italia (PASSI survey—managed by the local health authorities.34 This surveillance reports an overall uptake of 77% and 70% for cervical and breast cancer screening, respectively. It is also important to underline that the HPV test, which was authorised as a primary screening test instead of the Pap test in women older than 30–35 years in January 2013 by the Italian Ministry of Health, was available only through some pilot projects until 2014. Given that the NHIS interviews were conducted in 2012–2013 and that the questions referred to tests undergone in the three preceding years, obviously very few women had been invited to HPV screening at that point.20 29 43 Among the strengths of this study to be mentioned is the enormous information potential of the Istat survey, both at the individual and at the family level, offering a very rich description of individual women, their families and their socioeconomic status. Unfortunately, for this study, we had access to a restricted dataset of the NHIS. Therefore, the association between screening uptake and some potentially relevant information, as the family composition or the citizenship of the partner, could not be studied.

Another strong point is the inclusion of an ecological variable on the screening offered from a second data source. The joint use of these two data sources made it possible to estimate the impact of screening programmes on overall screening uptake and on differences in screening uptake between regions taking into account different socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics.

Conclusions

Total coverage observed through the Italian NHIS is below the desired and acceptable levels recommended by the European Commission.

Screening programmes increase uptake and have the potential, when correctly implemented, to decrease geographical inequalities, although not those differences caused by individual attitudes towards health and prevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacqueline Costa for English language editing, Cecilia Fazioli for the English translation and Stefano Schiaroli for assistance with graphs and charts.

Footnotes

Contributors: AP, PGR and LG designed and initiated the study and wrote the manuscript. LF extracted the data, conducted statistical analysis, interpreted the findings and reviewed/edited the manuscript. BG conducted statistical analysis. ADN reviewed and edited the manuscript. MZ and CM contributed to the discussion and critically reviewed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The analyses were performed using data based on Istat’s surveys. In particular, we used Istat’s standard files (issued on request with a valid reason for research purposes and released free of charge and in compliance with the principle of statistical secrecy and protection of personal data). To acquire such files, it is necessary to register in the area of the Istat website dedicated to data use and to accept the terms of use. Data are available in different formats (TXT, STATA, SAS, R).

References

- 1. Osservatorio Nazionale Screening. I programmi di screening in Italia. 2014. http://www.osservatorionazionalescreening.it/sites/default/files/allegati/Screening_2014_web.pdf.

- 2. Giorgi D, Giordano L, Ventura L, et al. [Mammography breast cancer screening in Italy: 2010 survey]. Epidemiol Prev 2012;36:8–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Von Karsa L, Anttila A, Ronco G, et al. , Cancer screening in the European Union. Report on the implementation of the Council Recommendation on cancer screening. First report. Luxembourg: European Commission, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, et al. , European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Luxembourg: European Commission. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zappa M, Carozzi FM, Giordano L, et al. The diffusion of screening programmes in Italy, years 2011-2012. Epidemiol Prev 2015;39:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giorgi Rossi P, Camilloni L, Cogo C, et al. Methods to increase participation in cancer screening programmes]. Epidemiol Prev 2012;36:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. ISTAT. La prevenzione dei tumori femminili in Italia il ricorso a Pap test e mammografia. Anni 2004-2005. Roma 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giorgi Rossi P, Carrozzi G, Federici A, et al. Invitation coverage and participation in Italian cervical, breast and colorectal cancer screening programmes. J Med Screen 2018;25:17–23. 10.1177/0969141317704476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health program planning: an educational and ecological approach. 4th ed New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Federici A, Guarino A, Serantoni G. Adesione ai programmi di screening di prevenzione oncologica: proposta di una modellizzazione dei risultati di revisione della letteratura secondo il Modello PRECEDE-PROCEED. Epidemiol Prev 2012;36:1–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palència L, Espelt A, Rodríguez-Sanz M, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening practices in Europe: influence of the type of screening program. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:757–65. 10.1093/ije/dyq003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jepson R, Clegg A, Forbes C, et al. The determinants of screening uptake and interventions for increasing uptake: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2000;4 i–vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Labeit A, Peinemann F, Baker R. Utilisation of preventative health check-ups in the UK: findings from individual-level repeated cross-sectional data from 1992 to 2008. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003387 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zappa M, Castiglione G, Giorgi D, et al. Re: Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:465 10.1093/jnci/90.6.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wools A, Dapper EA, de Leeuw JR. Colorectal cancer screening participation: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26:158–68. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Douglas E, Waller J, Duffy SW, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in breast and cervical screening coverage in England: are we closing the gap? J Med Screen 2016;23:98–103. 10.1177/0969141315600192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. ISTAT. Fattori di rischio e tutela della salute — Indagine multiscopo sulle famiglie italiane “Prevenzione dei tumori femminili: ricorso a pap test e mammografia” anni 2004/2005. 2006. http://www3.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/non_calendario/20061204_00/testointegrale.pdf

- 18. ISTAT. Multiscopo sulle famiglie: condizioni di salute e ricorso ai servizi sanitari. 2013. http://siqual.istat.it/SIQual/visualizza.do?id=0071201

- 19. Ronco G, Giorgi Rossi P, Giubilato P, et al. A first survey of HPV-based screening in routine cervical cancer screening in Italy. Epidemiol Prev 2015;39:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ronco G, Giubilato P, Carozzi F, et al. Extension of organized cervical cancer screening programmes in Italy and their process indicators, 2011-2012 activity. Epidemiol Prev 2015;39:61–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ventura L, Giorgi D, Giordano L, et al. Mammographic breast cancer screening in Italy: 2011-2012 survey. Epidemiol Prev 2015;39:21–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anttila A, Ronco G, Nicula F, et al. Organization of cytology-based and HPV-based cervical cancer screening : Anttila A, Arbyn M, De Vuyst H, Publications Office of the European Union. 2nd edition Luxembourg: European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening, 2015:69–108. supplements: pp. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nygård JF, Skare GB, Thoresen SØ. The cervical cancer screening programme in Norway, 1992-2000: changes in Pap smear coverage and incidence of cervical cancer. J Med Screen 2002;9:86–91. 10.1136/jms.9.2.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferroni E, Camilloni L, Jimenez B, et al. How to increase uptake in oncologic screening: a systematic review of studies comparing population-based screening programs and spontaneous access. Prev Med 2012;55:587–96. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Francovich L, Di Napoli A, Giorgi Rossi P, et al. [Cervical and breast cancer screening among immigrant women resident in Italy]. Epidemiol Prev 2017;41:18–25. doi:10.19191/EP17.3-4S1.P018.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sabates R, Feinstein L. The role of education in the uptake of preventative health care: the case of cervical screening in Britain. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:2998–3010. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sabates R, Feinstein L. Do income effects mask social and behavioural factors when looking at universal health care provision? Int J Public Health 2008;53:23–30. 10.1007/s00038-007-6096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Federici A, Poletti P, Guarino A, et al. Garantire la partecipazione consapevole: Federici A, Screening - Profilo complesso di assistenza. Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico, 2007:252–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carrozzi G, Sampaolo L, Bolognesi L, et al. Cancer screening uptake: association with individual characteristics, geographic distribution, and time trends in Italy. Epidemiol Prev 2015;39:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pacelli B, Carretta E, Spadea T, et al. Does breast cancer screening level health inequalities out? A population-based study in an Italian region. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:280–5. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Puliti D, Miccinesi G, Manneschi G, et al. Does an organised screening programme reduce the inequalities in breast cancer survival? Ann Oncol 2012;23:319–23. 10.1093/annonc/mdr121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spadea T, Bellini S, Kunst A, et al. The impact of interventions to improve attendance in female cancer screening among lower socioeconomic groups: a review. Prev Med 2010;50:159–64. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giorgi Rossi P, Baldacchini F, Ronco G. The possible effects on socio-economic inequalities of introducing HPV testing as primary test in cervical cancer screening programs. Front Oncol 2014;4:20 10.3389/fonc.2014.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lagerlund M, Bellocco R, Karlsson P, et al. Socio-economic factors and breast cancer survival-a population-based cohort study (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control 2005;16:419–30. 10.1007/s10552-004-6255-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Louwman WJ, van de Poll-Franse LV, Fracheboud J, et al. Impact of a programme of mass mammography screening for breast cancer on socio-economic variation in survival: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;105:369–75. 10.1007/s10549-006-9464-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Halmin M, Bellocco R, Lagerlund M, et al. Long-term inequalities in breast cancer survival-a ten year follow-up study of patients managed within a National Health Care System (Sweden). Acta Oncol 2008;47:216–24. 10.1080/02841860701769768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bankhead CR, Brett J, Bukach C, et al. The impact of screening on future health-promoting behaviours and health beliefs: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2003;7:1–92. 10.3310/hta7420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Venkataraman K, Wee HL, Ng SH, et al. Determinants of individuals' participation in integrated chronic disease screening in Singapore. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:1242–50. 10.1136/jech-2016-207404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grady D. Look for cancer, and find it!: New York Times, 2014. http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/07/look-for-cancer-and-find-it/. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gøtzsche PC, Hartling OJ, Nielsen M, et al. Breast screening: the facts-or maybe not. BMJ 2009;338:b86 10.1136/bmj.b86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Volpi R. L’amara medicina. Come la sanità italiana ha sbagliato strada. Milano: Feltrinelli, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ronco G, Segnan N, Giordano L, et al. Interaction of spontaneous and organised screening for cervical cancer in Turin, Italy. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:1262–7. 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Giorgi Rossi P, Esposito G, Brezzi S, et al. Estimation of Pap-test coverage in an area with an organised screening program: challenges for survey methods. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:36 10.1186/1472-6963-6-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.