Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency of select adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among a sample of American Indian (AI) adults living with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the associations between ACEs and self-rated physical and mental health. We also examined associations between sociocultural factors and health, including possible buffering processes.

Design

Survey data for this observational study were collected using computer-assisted survey interviewing techniques between 2013 and 2015.

Setting

Participants were randomly selected from AI tribal clinic facilities on five reservations in the upper Midwestern USA.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of T2D, age 18 years or older and self-identified as AI. The sample includes n=192 adults (55.7% female; mean age=46.3 years).

Primary measures

We assessed nine ACEs related to household dysfunction and child maltreatment. Independent variables included social support, diabetes support and two cultural factors: spiritual activities and connectedness. Primary outcomes were self-rated physical and mental health.

Results

An average of 3.05 ACEs were reported by participants and 81.9% (n=149) said they had experienced at least one ACE. Controlling for gender, age and income, ACEs were negatively associated with self-rated physical and mental health (p<0.05). Connectedness and social support were positively and significantly associated with physical and mental health. Involvement in spiritual activities was positively associated with mental health and diabetes-specific support was positively associated with physical health. Social support and diabetes-specific social support moderated associations between ACEs and physical health.

Conclusions

This research demonstrates inverse associations between ACEs and well-being of adult AI patients with diabetes. The findings further demonstrate the promise of social and cultural integration as a critical component of wellness, a point of relevance for all cultures. Health professionals can use findings from this study to augment their assessment of patients and guide them to health-promoting social support services and resources for cultural involvement.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, ACEs, American Indians, type 2 diabetes, culture

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first quantitative observational study of which we are aware to examine American Indian (AI) adult cultural and social protective factors in the face of earlier life adversities, including moderating relationships between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and adult self-rated mental and physical health.

Study scope and methodology was developed using community-based participatory research principles to promote authentic researcher/community member collaboration.

We contribute to a limited body of literature on ACEs and AI health by assessing ACE exposure and correlates for a clinical sample of Native adults.

Retrospective reports of ACEs that may involve systematic error including recall bias should be considered when interpreting findings.

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are early life stressful situations or traumatic events that often co-occur and are potent determinants of health linked to increased morbidity and mortality across the life course.1–9 The foundational Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Kaiser Permanente ACEs retrospective adult studies (Kaiser/CDC studies) identified a set of 8–10 childhood stressors including childhood emotional, physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect, witnessing intimate partner violence, parental separation and living with a substance abusing, mentally ill or incarcerated household member.5 6 These childhood stressors, or ACEs, have been shown to correspond with later life outcomes, such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), substance abuse and suicide attempts, with graded, positive relationships between the number of ACE exposures and risk for health outcomes.5 6 10 Adaptations of the Kaiser/CDC indexes have expanded ACE criteria to include, for example, peer isolation and rejection,11 peer victimisation,12 community level indicators like community violence12 and poverty.13 In the absence of protective factors, existing evidence suggests that early trauma and toxic stress can have lasting effects on physical and mental health.3 5 6 11

The emerging literature on ACEs among the American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) population has identified disproportionately high rates of ACEs and childhood stressors that are associated with multiple health outcomes including suicidality,7 substance misuse,8 diabetes14 and worse mental health including depressive symptoms.15 16 There is also movement to identify ACEs appropriate for AI/AN culture and context, such as historical loss associated symptoms and discrimination.7 Elevated and unique experiences with ACEs offer explanation for the pronounced health inequities experienced by AI/AN communities, including heightened rates of T2D. For example, data from 2013 to 2015 indicated adult overall prevalence of T2D for AI/ANs was 15.1%, versus 7.4% for non-Hispanic whites.17 Further, T2D represents a modern epidemic among AI/ANs, especially considering that prior to the 1940s, the diagnosis was relatively uncommon for this demographic.18

In the wake of such compelling evidence that ACEs can lead to serious health consequences, researchers have begun identifying factors that may provide a protective effect against ACE impacts.19 One way in which protective factors operate is through the fostering, building and exertion of resilience as an ability to overcome significant life stressors.20–24 In a US sample, factors such as sense of community have been shown to have direct and indirect protective effects on ACEs, including moderating roles for the impact of ACEs on adult mental health.25

Resilience promotion is not a new concept within Tribal communities. AI/ANs have longstanding traditional knowledge that include instructions on how to stay well and thrive, and Indigenous theoretical literature supports the assertion that sociocultural resources and cultural participation is health-promoting.26–28 AI/AN resilience is dynamic and accessed through familial, communal and cultural knowledge and expressions (eg, traditional activity participation, spiritual practices, positive identity promotion, social support, feelings of connectedness to family and nature).26 28 These deeply rooted beliefs and practices have been identified as multilevel factors that can buffer poor outcomes, strengthen resilience and promote health.29

Preventing ACEs and increasing access to and participation in resilience-building opportunities could contribute to closing the health equity gap for AI communities. An examination of moderating and health promoting factors is particularly salient for Tribal communities given complex health service delivery systems and limited systemic resources for monitoring and addressing behavioural health on reservations.21 30 Despite this great need, few studies have examined AI/AN-specific protective factors or resilience contributors in the context of ACEs. As an exception, Burnette and colleagues (2015) found that social support had a protective effect on depressive symptoms among AI/AN older adults who experienced ACEs.15 In another study, youth who experienced child maltreatment and other stressors had a reduced likelihood of suicidality if they discussed problems with friends or family and reported connectedness with family.30 However, no AI/AN-specific studies of which we are aware have investigated adult cultural and social protective factors in the face of earlier life adversities and their potential for moderating the relationship between ACEs and adult self-rated mental and physical health.

The purpose of this study is to (1) determine the frequency of select ACEs within a sample of AI/AN adults living with T2D and (2) examine associations between ACEs, social supports, cultural factors and self-rated physical and mental health. Three hypotheses guided our inquiry:

H1: ACEs will be negatively associated with self-reported physical and mental health status.

H2: Social support (general and diabetes-specific) and Indigenous cultural factors will be positively associated with self-reported physical and mental health status.

H3: Social support and cultural factors will buffer (moderate) the associations between ACEs and physical and mental health.

Methods

The Maawaji’ idi-oog Mino-ayaawin (Gathering for Health) project is a community-based participatory research collaboration between the University of Minnesota and five AI (ie, Ojibwe) communities. The primary purpose of the study was to understand sources of stress and examine their impact on T2D-related outcomes for AIs. Tribal resolutions supporting the project were granted by all five tribal nation governments.

Patient and public involvement

Community Research Councils (CRCs) from each tribe worked closely with the university research team to develop and implement study protocols, participate in data collection, interpretation and dissemination. Members of the CRCs included patients living with T2D, patient providers, community members and elders. As such, patient perspectives were incorporated into the design and conduct of this study. All CRCs read and/or provided comments on this manuscript prior to journal submission, and the paper was approved for submission by the Indian Health Service (IHS) National Institutional Review Board. Participants received a mailed infographic summarising major overall study results. In addition, the research team has/will continue to present findings within each tribal community via written technical reports and in-person presentations at local health fairs, tribal council meetings and public gatherings.

Procedure and sample

The study involved two major phases: (1) a qualitative step including two sets of focus groups to identify salient community stressors and adapt/develop survey measures and (2) a quantitative phase including survey data from computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI; details below). The goal of this process was to maximise measurement validity for local culture and contexts. Prior to CAPI field entry, we also piloted any adapted or new measures with a convenience sample of AI participants and asked for open-ended feedback on question applicability and comprehension. Feedback from pilot surveys permitted us to further refine measures in collaboration with CRC members. Data presented in this study are from Phase II CAPI responses.

Staff at each IHS clinic site generated simple random samples for Phase II study recruitment from patient records. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of T2D, age 18 years or older and self-identified as AI/AN. A total of 194 participants enrolled in the study, representing a baseline response rate of 67%.

Clinic staff sent study letters of invitation and brochures to residences of randomly selected patients. Non-refusing individuals were contacted and screened for eligibility by trained community interviewers. Visits were scheduled at a location of participants’ choosing, at which time interviewers gathered signed informed consent and HIPAA authorisation forms prior to administering surveys. We analysed responses from the 192 participants for which we have baseline CAPI completed from 2013 to 2015. Participants received a $50 incentive and a small, culturally meaningful gift for their participation.

Measures

Three control variables were included in analyses: age (in years), gender (male=0, female=1) and per capita household income were each assessed via self-report survey responses. Two dependent variables, self-rated mental health and self-rated physical health, each ranged in value from 0 (poor) to 4 (excellent); thus, higher scores indicate better health. A continuous ACEs measure was created by summing affirmative responses to nine experiences related to household dysfunction, and child maltreatment; participants were included in this continuous measure if they answered at least five of the nine ACE items (n=182; Cronbach’s alpha=0.77).

Several protective independent variables were also included. Social support was assessed by nine items adapted from a previous measure of perceived emotional and instrumental support received from others.31 Example items include: there is at least one person I can share most things with; I have someone to help me if I am physically unwell; I feel that I have a circle of people who value me and when I am feeling down, there is someone I can lean on (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89). Diabetes-specific support (adapted from Fitzgerald)32 includes five items and assesses perceived support directly related to diabetes management including help to follow a healthy meal plan, handle feelings about diabetes, and test (my) blood sugar (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86). Traditional spiritual activities include summed ‘yes’ responses to nine spiritually relevant cultural activities, such as seeking advice/guidance from a spiritual advisor or participating in a sweat lodge, which were engaged in during the prior year (Cronbach’s alpha=0.81). We also used an adapted Awareness of Connectedness33 measure that included six items assessing degree of connection to nature, family and community (eg, I feel connected to nature; When I am hurting, my family hurts with me; My community’s happiness is a part of my happiness; Cronbach’s alpha=0.74). A full listing of survey measures included in this manuscript is provided as an online supplementary file.

bmjopen-2018-022265supp001.pdf (114.8KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS V.24 to conduct all analyses with list-wise deletion of missing values, including ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses for multivariate models. There were few missing cases across variables; full sample responses were given for age, gender, income and spiritual activities, and missing data for remaining variables ranges from 1 to 4 cases total, with the exception of individual ACE items (table 1). We generated a total of eight separate OLS models (table 2) to examine the associations between the four hypothesised protective factors and their potentially moderating relationships for each of the two outcome variables (mental and physical health) after accounting for controls. Tests of moderation included a multiplicative interaction term for each protective variable × ACE scores.

Table 1.

Adverse childhood experiences among American Indian adults living with type 2 diabetes

| Never/No | At least once/Yes | |

| When you were growing up, did you live with a household member who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or misused street or prescription drugs? (n=181) | 51.9% | 48.1% |

| When you were growing up, did you live with a household member who was depressed, mentally ill or suicidal? (n=180) | 78.3% | 21.7% |

| When you were growing up, did you live with a household member who was ever sent to jail or prison? (n=179) | 68.2% | 31.8% |

| When you were growing up, how often did you see or hear a parent or household member in your home being slapped, kicked, punched or beaten up? (n=180) | 52.2% | 47.8% |

| When you were growing up, how often did a parent, guardian or other household member yell, scream, swear at you, insult you or humiliate you? (n=182) | 51.1% | 48.9% |

| When you were growing up, how often did a parent, guardian or other household member spank you, slap you, kick you, punch you or beat you up? (n=179) | 43.6% | 56.4% |

| When you were growing up, how often did someone touch or fondle you in a sexual way when you did not want them to? (n=179) | 76.5% | 23.5% |

| When you were growing up, how often did someone make you touch their body in a sexual way when you did not want them to? (n=177) | 86.4% | 13.6% |

| When you were growing up, how often did someone actually have oral, anal or vaginal intercourse when you did not want them to? (n=181) | 83.4% | 16.6% |

Table 2.

Results from ordinary least squares regression analyses

| Mental health | Physical health | Mental health | Physical health | Mental health | Physical health | Mental health | Physical health | |||||||||

| N=176 | N=177 | N=176 | N=177 | |||||||||||||

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Age | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.08 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.03 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.09 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.04 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.06 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.02 | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.07 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.01 |

| Gender | −0.15 (0.15) | −0.07 | −0.02 (0.13) | −0.01 | −0.15 (0.14) | −0.08 | −0.02 (0.13) | −0.01 | −0.23 (0.14) | −0.12† | −0.05 (0.13) | −0.03 | −0.13 (0.15) | −0.07 | 0.05 (0.13) | 0.03 |

| Per capita HH income | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.22** | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.18* | 0.02(0.01) | 0.20** | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.15* | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.15* | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.14† | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.20** | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.15† |

| ACEs | −0.09 (0.03) | −0.23** | −0.08 (0.03) | −0.22** | −0.08 (0.03) | −0.20** | −0.07 (0.03) | −0.20** | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.16* | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.17* | −0.07 (0.30) | −0.18* | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.17* |

| Spiritual activities | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.15* | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.07 | ||||||||||||

| Awareness of connectedness | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.18* | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.23** | ||||||||||||

| Social support | 0.50 (0.10) | 0.35*** | 0.27 (0.10) | 0.20** | ||||||||||||

| Social support × ACEs | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.14† | ||||||||||||||

| Diabetes specific Support | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.10 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.21** | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes support × ACEs | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.15* | ||||||||||||||

*P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; ***P≤0.001.

†P≤0.10; two-tailed tests.

ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; HH, household.

Results

The average age of the study participants was 46.3 years (SD=12.2), mean per capita household income was $9767.00 and slightly more than half were female (55.7%). Frequencies of nine ACEs appear in table 1. An average of 3.05 (SD=2.46) ACEs were reported by participants and 81.9% (n=149) reported at least one ACE (not displayed).

Table 2 displays results of OLS regression analyses. As hypothesised (H1), across all models and controlling for gender, age and income, ACEs were negatively associated with mental and physical health. Also as hypothesised (H2), involvement in spiritual activities, stronger awareness of connectedness, social support and diabetes-specific support were all positively and significantly associated with self-reported mental and/or physical health in these models. Two of the control variables were also related to health in the multivariate analyses. Per capita household income was significantly and positively associated with mental and physical health across all models, and being female was associated with worse mental health in one model only.

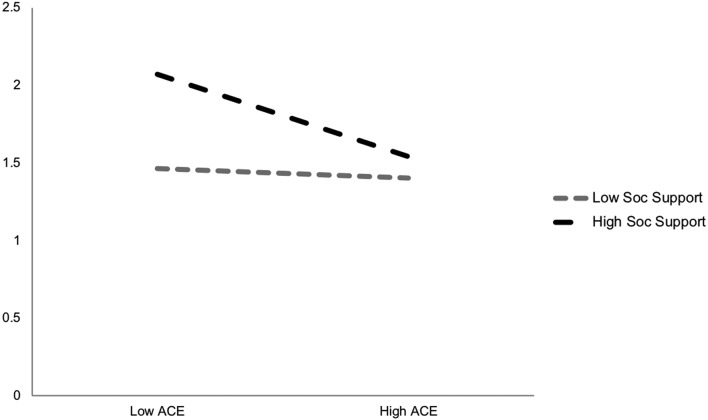

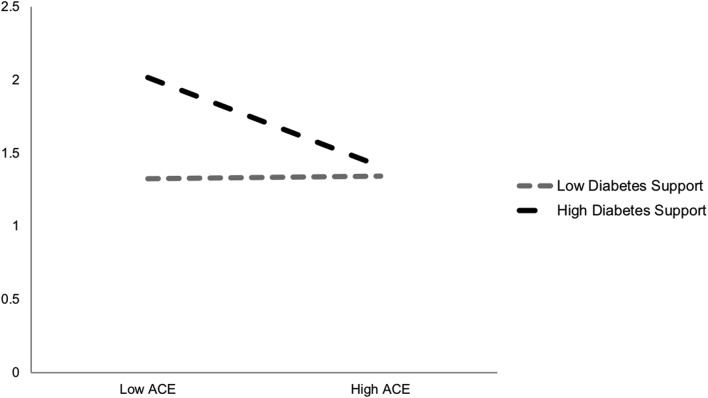

We included interaction terms for each of the protective factors by ACEs index score for all independent variables; two of these emerged as statistically significant and are plotted in figures 1 and 2. As shown and in partial support of the third hypothesis (H3), social support and diabetes-specific support moderated the negative associations between ACEs and physical health. More specifically, physical health ratings were highest (better) for those reporting high support and low ACEs. Even when reporting higher ACEs, those in high support contexts still had better self-reported physical health than those with lower ACE scores but less supportive environments.

Figure 1.

Self-rated physical health by ACE exposure and social support. ACE, adverse childhood experience.

Figure 2.

Self-rated physical health by ACE exposure and diabetes-specific support. ACE, adverse childhood experience.

Discussion

This study adds important evidence to the limited research on ACEs and T2D among AIs who have a demonstrated higher prevalence of both compared with non-Indigenous US populations.7 17 In this multisite community study, cultural and social indicators were linked to better mental and physical health even when accounting for ACEs. We also found partial evidence for the moderating role of social support on associations between ACEs and health.

Approximately 82% of this AI sample reported experiencing at least one ACE. Our finding is much higher than the less than two-thirds of non-Native adults who report one or more ACEs in the now classic Kaiser/CDC study.34 Our percentage of 82% in this Midwest AI sample is consistent with the 78.1% minimum exposure rate (one or more ACE) reported by adolescent AIs on one northern plains reservation7 and the 86% of participants in a seven tribe study.8

As hypothesised, self-rated physical and mental health were negatively associated with ACEs for this sample of adults managing T2D, a complex chronic disease. This is not surprising given what is known from research showing strong associations between ACEs and health outcomes including T2D itself.35–37 As many AI/ANs exhibit drastic health disparities, these conclusions are useful to public health and tribal health systems for consideration in long-term diabetes reduction strategies. Primary and secondary prevention efforts targeting ACE exposures and intermediate health outcomes (eg, behavioural health), respectively, may reduce the prevalence of T2D within Tribal communities.

Higher levels of connectedness and social support were associated with better mental and physical health; diabetes-specific support was associated with better physical health, and spiritual activity involvement was related to better mental health. We thus advance the literature by documenting protective associations between Indigenous cultural factors (ie, involvement in spiritual activities and connectedness) and health that persist even when accounting for ACE exposures and demographics. Cultural connectedness, social support and traditional practices as wellness promoting factors are widely understood within Tribal communities. Therefore, this research supports Indigenous knowledge and underscores the critical importance of ‘a community-based prevention approach [that] recognises the inherent knowledge of community members and their expertise’.38

While social support has a well-documented positive impact on patients with diabetes,39–41 we add to this literature by demonstrating that adult support appears to moderate the harms of childhood adversities among AIs. That is, our findings suggest that adulthood social support networks may buffer the negative relationships between ACEs and health. This includes diabetes-specific support for AIs diagnosed with T2D. Diabetes interventions promoting socially supportive environments may prove useful for better prognosis.

Our findings also revealed a consistent, inverse relationship between per capita household income and health status. Poverty is a fundamental determinant of health driving health inequities,42 43 and pervasive poverty impacts many reservation communities including those participating in this study. The protective impact of increasing incomes documented here lends evidence to the importance of addressing structural issues related to health including unemployment and low-paying jobs.44 45 In addition, gender emerged as a significant correlate of mental health in one of the models where women reported worse mental health than men. Although this was not a robust finding in these analyses, it is consistent with prior research indicating higher levels of internalising symptoms in females relative to males.46

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations for consideration. First, retrospective ACE studies may involve systematic error such as recall bias and false negative findings.47 Measurement and methodology differences hamper our ability to draw firm conclusions about the prevalence of AI/AN ACEs shown here and those documented nationally. ACEs reflected in this study are similar to most others in that they rely on a set of childhood stressors developed for mostly white, middle-class individuals with health insurance and who lived in Southern California; as such, results should be interpreted with these considerations in mind. A host of additional adversities including AI/AN specific ACEs are beginning to be addressed7 and deserve additional attention in future research. Given the variability in the types and severity of ACEs potentially experienced across cultures and community context, our estimates may be conservative and underscore the importance of culturally meaningful ACEs and placed-based assessments as a regular part of diabetes care and healthcare in general.7 Future research should include identification of specific forms and types of childhood stressors as well as the severity and frequency of the exposure that are particularly harmful to Native people alongside appraisal of sociocultural contexts that promote healing and well-being.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate how cultural and family supports relate to better health and in certain cases ameliorate the harms of ACEs among patients with T2D who face the complexities of managing chronic disease care. For policy-makers, our work suggests that funding allocations could support community-level resilience building activities and thus move beyond individual-level behaviour change (eg, diet, exercise). Specifically, programmes that enhance social support and include opportunities for cultural connectedness should be encouraged.

For health professionals, this research highlights the importance of life-course histories to assess childhood experiences and the lingering impact of childhood experiences on adult AI well-being. At the same time, providers including diabetes care professionals should encourage strategies for promoting help-seeking skills, social belonging and cultural activity participation for patients, particularly among those reporting a multitude of childhood adversities. Such support and encouragement could prove beneficial in promoting physical and mental health. These results also support the work of programme development staff in tribal communities who regularly engage in efforts to incorporate cultural group activities as wellness promotion and prevention mechanisms. These implications can inform wider health promotion strategies within and outside the healthcare system. For example, tribes may want to incorporate research findings into their design of trauma-informed care strategies and integrated behavioural healthcare. Finally, these findings have implications for health promotion across all cultures by highlighting the potential for sociocultural integration to improve human wellness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the clinical and community-based members of the Gathering for Health Team, including Community Research Council members and interviewers: Sidnee Kellar, Rose Barber, Robert Miller, Tweed Shuman, Lorraine Smith, Sandy Zeznanski, Patty Subera, Tracy Martin, Geraldine Whiteman, Lisa Perry, Trisha Prentice, Alexis Mason, Charity Prentice-Pemberton, Kathy Dudley, Romona Nelson, Eileen Miller, Geraldine Brun, Murphy Thomas, Mary Sikora-Petersen, Tina Handeland, GayeAnn Allen, Frances Whitfield, Phillip Chapman, Sr., Sonya Psuik, Hope Williams, Betty Jo Graveen, Daniel Chapman, Jr., Doris Isham, Stan Day, Jane Villebrun, Beverly Steel, Muriel Deegan, Peggy Connor, Michael Connor, Ray E. Villebrun, Sr., Pam Hughes, Cindy McDougall, Melanie McMichael, Robert Thompson and Sandra Kier. We also acknowledge Jacquelyn Campbell, PhD, RN, FAAN for her invaluable expertise and comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: TNB was responsible for drafting the literature review, discussion and conclusions sections. JHLE edited and added substantive content to the manuscript. MLW performed data analyses and drafted methods and results sections and oversaw data collection. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DK091250 (M L Walls, PI).

Disclaimer: The contents of this manuscript are attributable to the authors and do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of the NIH.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Project methodology and human subjects approval was granted by the University of Minnesota (IRB) and National Indian Health Service IRBs.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data sharing available.

References

- 1. Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53:1001–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA 2001;286:3089–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav 2002;27:713–25. 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00204-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: implications for health and social services. Violence Vict 2002;17:3–17. 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, et al. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics 2003;111:564–72. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brockie TN, Dana-Sacco G, Wallen GR, et al. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to ptsd, depression, poly-drug use and suicide attempt in reservation-based native American adolescents and young adults. Am J Community Psychol 2015;55(3-4):411–21 http://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10464-015-9721-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koss MP, Yuan NP, Dightman D, et al. Adverse childhood exposures and alcohol dependence among seven Native American tribes. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:238–44. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00195-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Acad Pediatr 2009;9:131–2. 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl 2004;28:771–84. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, et al. A revised inventory of adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse Negl 2015;48:13–21. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wade R, Cronholm PF, Fein JA, et al. Household and community-level Adverse Childhood Experiences and adult health outcomes in a diverse urban population. Child Abuse Negl 2016;52:135–45. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kenney MK, Singh GK. Adverse childhood experiences among American Indian/Alaska native children: the 2011-2012 national survey of children’s health. Scientifica 2016;2016:1–14. 10.1155/2016/7424239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang L, Beals J, Whitesell NR, et al. Stress burden and diabetes in two American Indian reservation communities. Diabetes Care 2008;31:427–9. 10.2337/dc07-2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burnette CE, Roh S, Lee KH, et al. A comparison of risk and protective factors related to depressive symptoms among American Indian and Caucasian older adults. Health Soc Work 2017;42:e15–e23. 10.1093/hsw/hlw055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roh S, Burnette CE, Lee KH, et al. Risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms among American Indian older adults: adverse childhood experiences and social support. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:371–80. 10.1080/13607863.2014.938603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. National diabetes statistics report. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- 18. West KM. Diabetes in American Indians and other native populations of the New World. Diabetes 1974;23:841–55. 10.2337/diab.23.10.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheong EV, Sinnott C, Dahly D, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression: perceived social support as a potential protective factor. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013228 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Center on the Developing Child, 2015. The science of resilience (In Brief). https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-the-science-of-resilience

- 21. Pollard JA, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW. Risk and protection: Are both necessary to understand diverse behavioral outcomes in adolescence? Soc Work Res 1999;23:145–58. 10.1093/swr/23.3.145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Allen J, Hopper K, Wexler L, et al. Mapping resilience pathways of Indigenous youth in five circumpolar communities. Transcult Psychiatry 2014;51:601–31. 10.1177/1363461513497232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khanlou N, Wray R. A whole community approach toward child and youth resilience promotion: a review of resilience literature. Int J Ment Health Addict 2014;12:64–79. 10.1007/s11469-013-9470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, et al. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2014;5:25338 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nurius PS, Logan-Greene P, Green S. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) within a social disadvantage framework: distinguishing unique, cumulative, and moderated contributions to adult mental health. J Prev Interv Community 2012;40:278–90. 10.1080/10852352.2012.707443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elm JH, Lewis JP, Walters KL, et al. "I’m in this world for a reason": resilience and recovery among American Indian and Alaska native two-spirit women. J Lesbian Stud 2016;20:352–71. 10.1080/10894160.2016.1152813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alcántara C, Gone JP, Joseph P. Reviewing suicide in Native American communities: situating risk and protective factors within a transactional-ecological framework. Death Stud 2007;31:457–77. 10.1080/07481180701244587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walters KL, Simoni JM. Reconceptualizing native women’s health: an "indigenist" stress-coping model. Am J Public Health 2002;92:520–4. 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henson M, Sabo S, Trujillo A, et al. Identifying Protective Factors to Promote Health in American Indian and Alaska Native Adolescents: A Literature Review. J Prim Prev 2017;38:5–26. 10.1007/s10935-016-0455-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Borowsky IW, Resnick MD, Ireland M, et al. Suicide attempts among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: risk and protective factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shakespeare-Finch J, Obst PL. The development of the 2-Way Social Support Scale: a measure of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support. J Pers Assess 2011;93:483–90. 10.1080/00223891.2011.594124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fitzgerald JT, Davis WK, Connell CM, et al. Development and validation of the Diabetes Care Profile. Eval Health Prof 1996;19:208–30. 10.1177/016327879601900205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mohatt NV, Fok CC, Burket R, et al. Assessment of awareness of connectedness as a culturally-based protective factor for Alaska native youth. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2011;17:444–55. 10.1037/a0025456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey ACE Module Data, 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy

- 35. Huang H, Yan P, Shan Z, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2015;64:1408–18. 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nurius PS, Fleming CM, Brindle E. Life Course pathways from adverse childhood experiences to adult physical health: a structural equation model. J Aging Health 2017;8:089826431772644 10.1177/0898264317726448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord 2004;82:217–25. 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2094–102. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gomes LC, Coelho ACM, Gomides DDS, et al. Contribution of family social support to the metabolic control of people with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Appl Nurs Res 2017;36:68–76. 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laursen KR, Hulman A, Witte DR, et al. Social relations, depressive symptoms, and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the english longitudinal study of ageing. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;126:86–94. 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dill EJ, Manson SM, Jiang L, et al. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss among American Indian and Alaska native participants in a diabetes prevention translational project. J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:1–10. 10.1155/2016/1546939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365:1099–104. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74234-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet 1991;337:1387–93. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schofield DJ, Callander EJ, Shrestha RN, et al. The association between labour force participation and being in income poverty amongst those with mental health problems. Aging Ment Health 2013;17:250–7. 10.1080/13607863.2012.727381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav 1995;Spec No:80–94. 10.2307/2626958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289:3095–105. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:260–73. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022265supp001.pdf (114.8KB, pdf)