Abstract

This case presents symptom resolution for a long-distance runner with chronic Achilles tendinopathy (AT), following a partial tear of his Achilles tendon. The patient reported a sudden pain during a morning run, with preserved function. Three hours postinjury, he was reviewed in a musculoskeletal clinic. An ultrasound scan confirmed a partial Achilles tear, associated with significant Doppler activity. His index of AT severity The Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment - Achilles Questionnaire (VISA-A) 4 hours postinjury was markedly higher compared with 2 weeks preinjury, indicating reduced symptom severity. A follow-up scan 4 weeks postinjury showed minimal mid-portion swelling and no signs of the tear. His VISA-A score showed continued symptom improvement. This case represents resolution of tendinopathic symptomatology post partial Achilles tear. While the natural histories of AT and Achilles tears remain unknown, this case may indicate that alongside the known role of loading, inflammation may be a secondary mediator central to the successful resolution of AT pain.

Keywords: tendonopathies, sports and exercise medicine, achilles tendinitis, tendon rupture

Background

The Achilles tendon is the strongest in the human body, subject to 6–8 times body weight during physical activity such as jumping.1 2 Symptomatic tendon conditions account for 30%–50% of sports injuries,3 with tendinopathy reported as the most common tendon disorder.4–9 Mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy (AT) is typically seen in repetitive high-impact activities such as running and jumping, with a reported prevalence of 11%–18% in runners.10 11 Non-athletic populations are also at risk, with 31% of individuals with AT having a sedentary lifestyle.12 With increased exposure to competitive and recreational sport, the incidence of AT rises, accounting for up to 4% of sport medicine clinic visits.13

In contrast to the identified structure and function of the Achilles tendon,5 its adaptive response to physical activity remains not fully elucidated.14 Equally, the role of structural changes, such as partial tears, in both pathogenesis and their association with AT symptoms, remains poorly understood.15 16 Tears are often described based on their degree and position.17 18 Of all tendon abnormalities on MRI presenting from referrals due to ankle pain, the majority of symptomatic Achilles cases were interstitial tears (61%), followed by partial tears (13%), complete tears (13%) and complex tears (9%).16 Recently, intratendinous tears of the Achilles tendon were suggested as a cause of achillodynia, especially in elite male athletes.19 Partial tears of the Achilles tendon are discussed in literature as resultant of impingement,20 however the role and natural history of small tears remains poorly understood.

Ultrasound use in the assessment of Achilles tears is fast and reliable,21 with good sensitivity and specificity for identifying tears.6 In the athletic population with chronic tendinopathy, sonographically demonstrable small and partial tears occur more frequently than in asymptomatic individuals.7

We present a case of a partial tear of mid-portion tendinopathic Achilles tendon, associated with a significant improvement of symptoms. This case suggests that AT symptoms may be associated with excessive loading through an abnormal aspect of the tendon, resulting in inflammatory reaction and chronic remodelling.

Case presentation

Presenting features

In our case, an otherwise healthy and physically active 34-year-old man with chronic AT developed a distal partial mid-portion tear of the Achilles tendon during running. He reported a sudden sharp pain during a slow morning run, with a backpack that was loaded with additional weight. This was followed by a 2–3 min long burning pain in the mid-portion region of his Achilles. Initial pain was severe enough for the patient to suspect a full thickness tear. However, Achilles function was preserved: he was able to plantar flex and perform single leg raises 2–3 min after the initial onset of pain, allowing him to continue running. The patient was reviewed 3 hours postonset in a musculoskeletal medical unit.

Medical and family history

The patient was 1.88 m tall and weighed 83 kg with a body mass index (BMI) of 23.5. He was right-leg dominant, with an 8-year history of left AT, and reported infrequent symptom flares (typically once a year) associated with increased loading, new training shoes or prolonged inactivity. The most recent aggravation occurred 4 weeks before the injury, following a 46 km hill run. Since this aggravation, the patient reported increased morning stiffness, alongside more significant mid-portion swelling and tenderness of the left Achilles tendon. The patient also had a 10-year history of left-sided sciatica due to L5/S1 disc protrusion, successfully managed with physiotherapy.

The patient was a non-competitive cross-country runner who accomplished three full marathons in the last 5 years. His weekly training routine consisted of 3–4 runs, with an average weekly distance of 40 km. He performed daily eccentric Achilles tendon training consisting of 80 heel drops with up to 30 kg additional weight.

Investigations

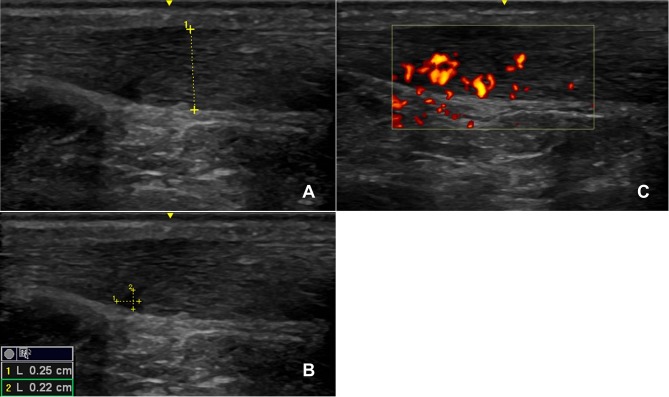

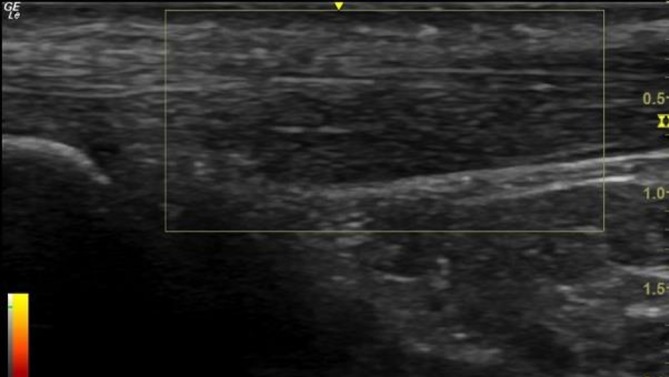

During the review 3 hours postinjury, an ultrasound scan was performed which confirmed a partial anterior Achilles tendon tear (figure 1A), showing mid-portion swelling with hypoechogenic structure anterior-mid tendon, and a wedge-like partial tear associated (figure 1B) with significant Doppler activity (figure 1C). The patient completed the validated VISA-A questionnaire, an index of the severity of AT,7 4 hours after the injury, scoring 97/100 (with a score of 100/100 being completely asymptomatic and a score 0/100 indicating maximum AT symptoms). Two weeks prior to the presented injury, the patient had undergone an ultrasound of his left Achilles in a sports injury clinic (figure 2) which showed mid-portion swelling with hypoechogenic aspect located predominantly on the anterior aspect of the tendon and associated with significant Doppler activity. At this scan, his VISA-A questionnaire score was 75/100. Postinjury, the main improvements were symptomatic and functional, in questionnaire items 1 (morning stiffness), 4 (pain walking downstairs) and 5 (pain after 10 single-leg raises).

Figure 1.

The left Achilles tendon 3 hours postinjury (A–C), with partial tear measuring 0.22 cm by 0.25 cm outlined (B). The tendon showed significant Doppler activity at the time of the scan (C). The GE 12 L linear array ultrasound transducer probe was used.

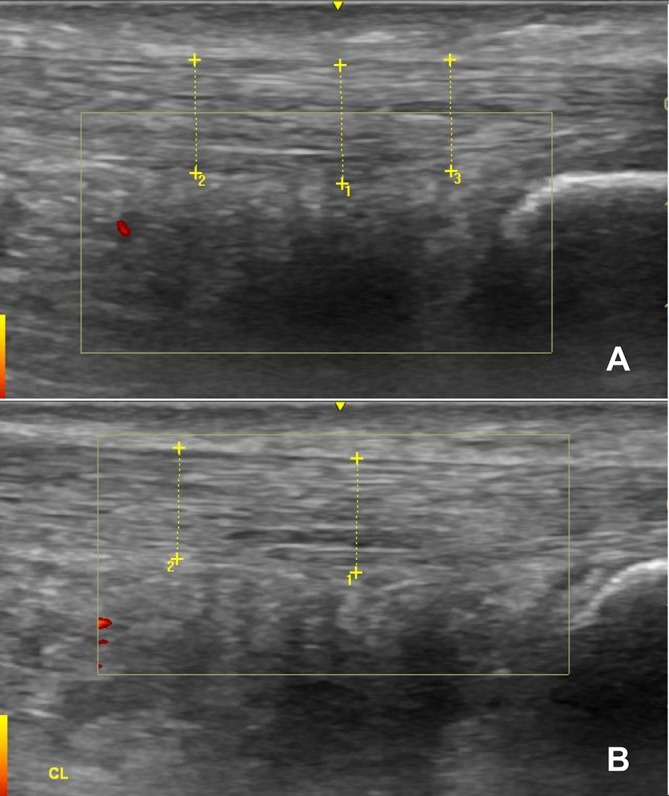

Figure 2.

The left Achilles Tendon 2 weeks prior to injury. The GE 12 L linear array ultrasound transducer probe was used.

Treatment

Following the partial tear, the patient suspended his eccentric exercise programme for 2 days. After 48 hours, he resumed a reduced eccentric exercise programme consisting of 40 heel drops with 20 kg extra weight per day (33% reduction compared with typical load).

During the first week postinjury, the patient reduced the amount of running training by 30% both in terms of speed and distance. He monitored for any symptoms of AT.

The patient did not use analgesia or anti-inflammatory medications during the course of the treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

Four weeks postinjury, the patient ran his first cross-country 100 km race, against medical advice. He completed the race, and reported no lower limb pain or weakness around the affected tendon.

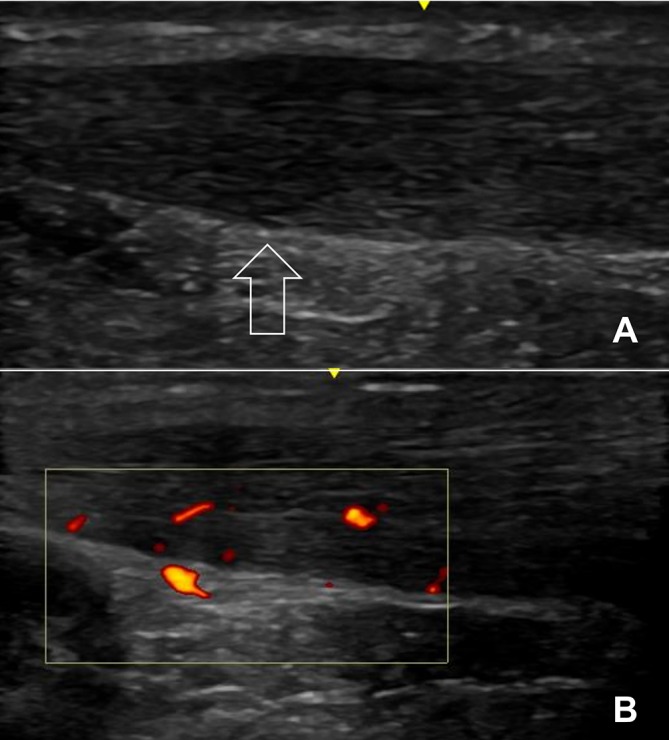

His VISA-A questionnaire score 1 week postrace (4 weeks postinjury) was 99/100. Relative to the previous scan, the ultrasound (figure 3) showed minimal mid-portion swelling, reduced Doppler activity in the anterior aspect (figure 3B) and reduced signs of a tendon tear (figure 3A; although still remains identifiable on the scan).

Figure 3.

The left Achilles tendon 2 weeks postinjury. There is reduced yet persistent evidence of tear pathology (A; arrow pointing towards the location of the original tear) compared with the scan at the time of injury. The tendon showed continued Doppler activity (B) which was reduced compared with the scan taken at the time of injury. The GE 12 L linear array ultrasound transducer probe was used.

Two years after sustaining the original injury, the patient was reviewed in a musculoskeletal clinic. His VISA-A questionnaire score remained 99/100, and the ultrasound of the affected tendon (figure 4A) showed no signs of the tear, with virtually absent Doppler activity. Ultrasound of the contralateral Achilles tendon carried out in the clinic (figure 4B) showed a very similar tendon structure to the affected side.

Figure 4.

Ultrasound scans of the patient’s affected (A) and contralateral (B) Achilles tendons 2 years after the injury. There is very little difference between the tendons structurally, and Doppler activity is virtually absent in both the scans.

Discussion

This case describes substantial improvement in both patient-reported symptomatic and functional outcome measures, concomitant with reduced swelling and pathology on ultrasound, following a distal partial mid-portion Achilles tear, and subsequent return to physical activity. Furthermore, participation in this relatively extreme form of endurance activity, representing a substantial increase in training volume beyond the initial postinjury conservative training volume 4 weeks after the tear, was associated with improvement in function, symptomatology and on ultrasound.

This is first time to the authors’ knowledge that an increase in loading in the acute postinjury phase has resulted in AT symptom improvement, from both the time of injury and substantially beyond preinjury chronic AT symptomatology.

Risk factors of AT

AT is characterised by morning stiffness, localised swelling and tenderness. Pain typically presents during loading, subsides with sustained activity, but with chronicity becomes persistent. The pathological stimulus for AT development is excessive loading. Other extrinsic factors include acute changes in the amount or type of load (eg, change in training routine), altered biomechanics, changes in training surface or footwear, and training errors.22 Intrinsic risk factors include adverse individual biomechanics, older age, higher BMI and metabolic dysregulation associated with dyslipidaemias and diabetes mellitus.23 The mid-portion of the Achilles (2–6 cm from the calcaneal insertion) has been described as the ‘critical zone’, most vulnerable to injury.24 Mid-portion AT injuries may be lesions traumatic, microtraumatic (following functional overload) or atraumatic (associated with dysmetabolic and inflammatory diseases).24

Physical activity, loading and tendinopathy

There is increasing awareness of the tendon response to physical activity; however, less research has considered the tendon’s response to strength training, compared with aerobic physical activity or stretching exercise.

Eccentric stretching programmes are used widely in the management of mid-portion Achilles tendinopathies with successful outcomes.25 Eccentric training has decreased tendon stiffness and pain in athletes with patellar tendinopathy,26 and tendon stiffness has been reported to decrease after eccentric, but not concentric, calf training in AT.27

Generalising the relationship between physical activity, loading and tendinopathy is complicated by differences in physiological tendon demands and the close relationship between tendon and its attaching muscle.28 29 Findings in tendon physiology have been based on animal studies, notably non-primate animal studies, and on isolated human cells which may not necessarily replicate the human system.27 Additionally, the association between structural changes during the pathogenesis of AT, and the development of pain, are poorly understood. While AT is associated with pathological changes at tissue level and on clinical imaging, these also occur in the asymptomatic patients.30

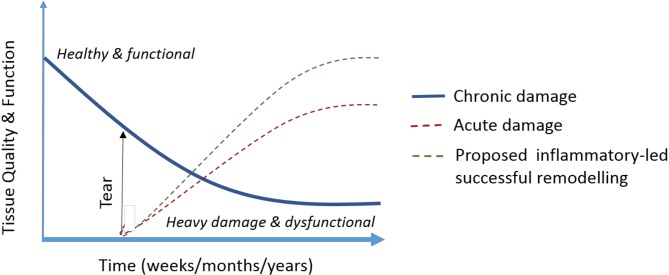

The above complexities and the question whether tendon response represents a physiological adaptation to loading or a degenerative pathological process culminating in tendinopathy have led to the development of theoretical models of tendinopathy. One example is the continuum model of tendinopathy which has also recently been revised to further consider pain and the continuum’s clinical relevance.31 32 A paradigm has also been presented to elucidate the effect of injury on tendon tissue quality and function, particularly given pre-existing chronic tendinopathic degeneration (figure 5).29 Within this, mechanical loading has been suggested as a ‘state switch’ between functional remodelling and the progression of chronic disease.29

Figure 5.

The effect of tendon injury (tear) on tissue quality and function in healthy tissue, and proposed capacity of injury and its inflammation to promote remodelling and increased function (adapted from Snedeker and Foolen29).

Tears, pain and function

The role and natural history of small tears is still poorly understood, although it has been suggested that a non-degenerative tendon will not tear without underlying degenerative tendinopathy.16 In a small study of athletes, all subjects with partial Achilles rupture (n=8) had evidence of three or more microtears in the mid-third of the Achilles, away from the site of rupture.7

While pain is central to the clinical diagnosis of tendinopathy, the discordance between tendon pathology and pain is established, and central to ineffective treatment of tendinopathy.

An interesting consideration of this case study is the relationship between loading (training volume), pain, symptomatology (VISA-A) and the Achilles tear. Acute and chronic inflammation, nociceptive pain and central sensitisation all have been considered as potentially having a role in the development and persistence of pain in tendinopathy.33–35

In the presented case, initial AT was associated with swelling on ultrasound, suggesting a chronic inflammatory response, probably as a result of the patient-reported biomechanical factors, for example, increasing training. The patient then partially ruptured his Achilles during weighted running which may be resultant of a combination of loading on potentially ‘degenerative’ (pathological) tissue, with evidence of further mid-portion swelling and significant Doppler activity on ultrasound prior to injury. This partial tear resulted in an acute on chronic inflammatory response. However, in contrast to the paradigm presented by Snedeker and Foolen,29 our patient reported an increase in tissue function, notably symptomatic function.

Tendon’s reparative capacity has been discussed as ‘an interplay between an ‘intrinsic compartment’ (fascicles of tendon cells and collagen) and ‘extrinsic compartment’ (synovium-like tissues connecting immune, vascular and nervous systems)’.29 In our case, it is possible that the tear itself promoted an extrinsic compartment inflammatory reparative response further to the existent localised mid-portion swelling which may have promoted tendon reparation in the specific aspect of the previously pathological AT tissue, leading to decreased symptom reporting from the patient. Reduced levels of inflammation have previously been seen in torn tendon tissue compared with tendinopathic tissue,34 and given the presence of chronic inflammation in tendinopathy,33 35 it is plausible that inflammatory response is a reactive process secondary to dysfunctional tendon loading.

Learning points.

Typical chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy (AT) can improve substantially following a partial tear of the Achilles.

Acute injury may have promoted a reparative inflammatory response for an individual with chronic AT.

The redistribution of loading through the tendon following the partial tear might be responsible for the symptomatic and sonographic improvement, particularly through previously abnormal tendon tissue.

Footnotes

Contributors: MMW was the primary investigator. He was behind the drafting of the article and its subsequent revision. SK was behind the concept of the article. He identified the case, collected the data required and approved the final version. TW was involved in the care of the patient and subsequent recruitment of the patient alongside gathering data for the case report. He performed the ultrasound scans of the patient and supplied the patient and technical information for the study. MAMD was responsible for revising the article, in particular the discussion section. She also played a key role in the literature review, and edited and approved the final version of the draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Paavola M, Kannus P, Järvinen Tah, et al. Achilles tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:2062–76. 10.2106/00004623-200211000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soma CA, Mandelbaum BR. Achilles tendon disorders. Clin Sports Med 1994;13:811–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Järvinen TAH, Kannus P, Maffulli N, et al. Achilles Tendon disorders: etiology and epidemiology. Foot Ankle Clin 2005;10:255–66. 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zafar MS, Mahmood A, Maffulli N. Basic science and clinical aspects of achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2009;17:190–7. 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181b37eb7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Buono A, Chan O, Maffulli N. Achilles tendon: functional anatomy and novel emerging models of imaging classification. Int Orthop 2013;37:715–21. 10.1007/s00264-012-1743-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartgerink P, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA, et al. Full- versus partial-thickness Achilles tendon tears: sonographic accuracy and characterization in 26 cases with surgical correlation. Radiology 2001;220:406–12. 10.1148/radiology.220.2.r01au41406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbon WW, Cooper JR, Radcliffe GS. Sonographic incidence of tendon microtears in athletes with chronic Achilles tendinosis. Br J Sports Med 1999;33:129–30. 10.1136/bjsm.33.2.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson JM, Cook JL, Purdam C, et al. The VISA-A questionnaire: a valid and reliable index of the clinical severity of Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:335–41. 10.1136/bjsm.35.5.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konrad A, Stafilidis S, Tilp M. Effects of acute static, ballistic, and PNF stretching exercise on the muscle and tendon tissue properties. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2017;27:1070–80. 10.1111/sms.12725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clement DB, Taunton JE, Smart GW, et al. A survey of overuse running injuries. Phys Sportsmed 1981;9:47–58. 10.1080/00913847.1981.11711077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krissoff WB, Ferris WD. Runners' Injuries. Phys Sportsmed 1979;7:53–64. 10.1080/00913847.1979.11710897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolf C, Movin T. Etiology, histopathology, and outcome of surgery in achillodynia. Foot Ankle Int 1997;18:565–9. 10.1177/107110079701800906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereaux MD, Lachmann SM. Athletes attending a sports injury clinic–a review. Br J Sports Med 1983;17:137–42. 10.1136/bjsm.17.4.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konrad A, Tilp M. Increased range of motion after static stretching is not due to changes in muscle and tendon structures. Clin Biomech 2014;29:636–42. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Sterkenburg MN, van Dijk CN. Mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: why painful? An evidence-based philosophy. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology. Arthroscopy 2011;19:1367–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haims AH, Schweitzer ME, Patel RS, et al. MR imaging of the Achilles tendon: overlap of findings in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Skeletal Radiol 2000;29:640–5. 10.1007/s002560000273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstabl R, Stiskal M, Neuhold A, et al. Classifying calcaneal tendon injury according to MRI findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73:683–5. 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schweitzer ME, Karasick D. MR imaging of disorders of the Achilles tendon. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;175:613–25. 10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan O, Morton S, Pritchard M, et al. Intratendinous tears of the Achilles tendon - a new pathology? Analysis of a large 4-year cohort. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2017;7:53–61. doi:10.11138/mltj/2017.7.1.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lohrer H. [Minimally invasive repair of an impingement induced partial tear of the anterior Achilles tendon in a top level athlete]. 2010:80–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Patel NN, Labib SA. The Achilles Tendon in healthy subjects: an anthropometric and ultrasound mapping study. J Foot Ankle Surg 2018;57:285–8. 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvist M. Achilles Tendon injuries in athletes. Sports Medicine 1994;18:173–201. 10.2165/00007256-199418030-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnan B, Bondi M, Pierantoni S, et al. The pathogenesis of Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg 2014;20:154–9. 10.1016/j.fas.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gervasio A, Bollani P, Biasio A. US in mid-portion Achilles tendon injury. J Ultrasound 2014;17:135–9. 10.1007/s40477-013-0023-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frizziero A, Trainito S, Oliva F, et al. The role of eccentric exercise in sport injuries rehabilitation. Br Med Bull 2014;110:47–75. 10.1093/bmb/ldu006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WC, Ng GY, Zhang ZJ, et al. Changes on tendon stiffness and clinical outcomes in athletes are associated with patellar tendinopathy after eccentric exercise. Clin J Sport Med 2017:1 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrissey D, Roskilly A, Twycross-Lewis R, et al. The effect of eccentric and concentric calf muscle training on Achilles tendon stiffness. Clin Rehabil 2011;25:238–47. 10.1177/0269215510382600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dean BJF, Dakin SG, Millar NL, et al. Review: Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of tendinopathy. Surgeon 2017;15:349–54. 10.1016/j.surge.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snedeker JG, Foolen J. Tendon injury and repair: a perspective on the basic mechanisms of tendon disease and future clinical therapy. Acta Biomater 2017;63:18–36. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peers KH, Brys PP, Lysens RJ. Correlation between power Doppler ultrasonography and clinical severity in Achilles tendinopathy. Int Orthop 2003;27:180–3. 10.1007/s00264-002-0426-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:409–16. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.051193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook JL, Rio E, Purdam CR, et al. Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: what is its merit in clinical practice and research? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1187–91. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dakin SG, Newton J, Martinez FO, et al. Chronic inflammation is a feature of Achilles tendinopathy and rupture. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:359–67. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dean BJ, Gettings P, Dakin SG, et al. Are inflammatory cells increased in painful human tendinopathy? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:216–20. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rio E, Moseley L, Purdam C, et al. The pain of tendinopathy: physiological or pathophysiological? Sports Med 2014;44:9–23. 10.1007/s40279-013-0096-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]