Abstract

McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) is characterized by the triad of precocious puberty, café au lait pigmentation, and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (FD) of bone, and is caused by post-zygotic somatic mutations—R201H or R201C—in the guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating (GNAS) gene. In the present study, a novel peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe with fluorescent labeling was designed to detect trace amounts of somatic mutant GNAS in a single tube reaction. The method was applied to screen GNAS mutations in six patients with MAS/FD. The results showed that the PNA probe assay could detect low abundant mutants in 200-fold excess of wild-type alleles. The GNAS mutation was found in three patients with severe disease (MAS) by using the assay. The other three patients with mild disease (having only FD) showed a wild-type result. This study has provided a simple method to detect trace amounts of GNAS mutants with high sensitivity in large amounts of wild-type DNA.

Keywords: peptide nucleic acid probe, sensitive detection, McCune-Albright syndrome, GNAS mutation

1. Introduction

McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) and fibrous dysplasia (FD) are believed to be caused by postzygotic somatic mutations in the alpha subunit of the stimulatory G-protein (Gsα), which is encoded by GNAS1 gene. The most frequently reported mutations are R201H or R201C [1,2,3], which result in a loss of the GTPase activity of Gsα and lead to constitutive activation of Gsα. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate is thus accumulated in the affected cells and disturbs normal cell function [4]. The mechanism of these somatic mutations of GNAS1 gene is not yet known. Because the GNAS1 mutations occur at different life stages, the genotypes of GNAS1 in different patients are mosaic, with different ratio of wild-type and mutant. The ratio and distribution of the mutant cells lead to a broad spectrum of diseases. The mild forms include monostotic FD and polyostotic FD; the most severe form is MAS, which is characterized by at least two of the following features: precocious puberty, café au lait pigmentation, and polyostotic FD [5]. MAS is a rare disease, with an estimated prevalence between 1/100,000 and 1/1,000,000.

MAS is usually diagnosed by applying bone biopsy and imaging methods such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. However, as the disease symptoms are diverse, molecular testing of GNAS mutation is helpful to establish the diagnosis. DNA samples for detecting GNAS mutations can be isolated from the skin [6], whole blood [5,7], and fibrous dysplasia lesions [2,8] of patients. Among them, blood is an especially useful source of the sample. Obtaining DNA from blood cells avoids the requirement of many invasive procedures, such as bone biopsy. However, the mosaic pattern of cells bearing the GNAS mutation may hamper the detection, as mutant GNAS alleles usually represent only a small proportion of the total number of GNAS alleles. The possibility of detection is proportional to the severity of the disease. Hence, a sensitive molecular test will increase the detection rate.

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) is a DNA mimic in which the deoxyribose phosphate backbone is replaced with a 2-aminoethylglycine backbone. A PNA oligomer can form a stable Watson–Crick pairing with complementary DNA, but the pairing is highly sensitive to mismatches [9]. Two different designs of PNA oligomer have been reported to detect GNAS mutations. The first is to use PNA as a clamp in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to inhibit the wild-type amplification [10,11,12]. Rare mutant PCR products are thus enriched, and can be analyzed by gel electrophoresis and direct sequencing. The second design is to label PNA with a fluorophore, serving as a sensor probe. It has been used to quantify mutant GNAS by melting profile [13]. However, the PNA sensor probe was added after PCR reaction, which needed multiple manipulation steps and increased contamination risk. In addition, this method was much less sensitive.

In the current study, we combined both designs to develop a simple reaction for detecting GNAS mutation (see Figure 1 for a schematic diagram). The fluorescence-labeled PNA was used not only to clamp wild-type amplification, but also to report mutant signal. This design has been successfully applied in the detection of KRAS mutations [14,15]. With this design, the enrichment of mutant PCR products and the detection of mutant genotype can be completed in a single tube without further laborious procedures. We used this novel PNA probe assay to screen GNAS mutation in blood samples of six patients with polyostotic FD/MAS and identified three with a GNAS mutation.

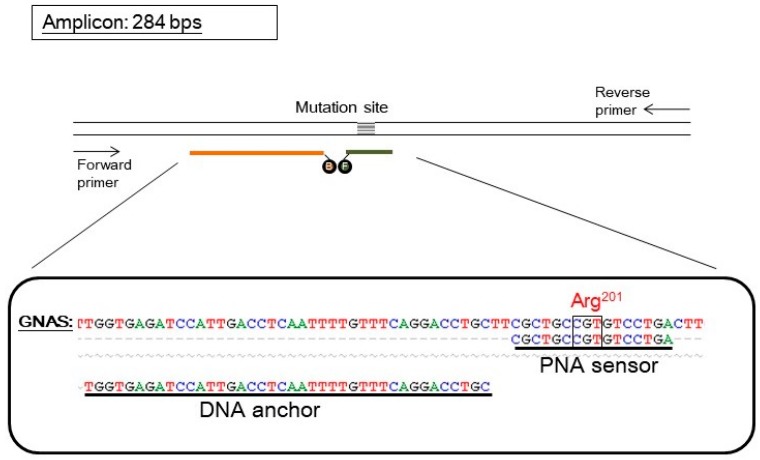

Figure 1.

The design of a PNA probe assay for detecting GNAS mutation. The upper part shows the scheme of oligonucleotides. The parallel lines represent a double-stranded DNA fragment of the GNAS gene. The pair of arrows represents the forward and reverse primers used in PCR that amplified the GNAS gene and generated an amplicon of 284 base pairs (bps). The probe set consisted of a PNA sensor probe (orange line) which covered the mutation site and was labeled with a fluorescein (represented by an “F”) and a DNA anchor probe (dark green line) labeled with Bodipy 630/650 (represented by a “B”). The two fluorophores can undergo Foster resonance energy transfer when both probes anneal on the same target GNAS fragment. The lower part shows the sequence alignment of wild-type GNAS, the PNA sensor probe, and the DNA anchor probe. The mutation site (arg201) is also indicated. For simplicity, the fluorophores are not shown.

2. Results

2.1. Assay Design

The PNA probe assay for GNAS mutation contained a pair of hybridization probes and a pair of PCR primers. A PNA oligomer was labeled with a fluorescein, and served as both PCR clamp and sensor probe. A DNA oligomer was labeled with a Bodipy 630/650, and served as an anchor probe. The pair of primers generated an amplicon of 284 base pairs (Figure 1). The PNA sequence was designed according to the wild-type GNAS; hence, it is perfectly complementary to the wild-type allele but has a mismatch to the mutant allele of GNAS.

The assay procedure included a PCR program and a melting analysis program on a capillary PCR instrument with a fluorescent detector. During the PCR program, the PNA bound tightly to the wild-type template and hindered its amplification. On the other hand, because of the existence of a mismatch, the PNA bound to the mutant template much more loosely and allowed its amplification. As a consequence, the PNA served as a PCR clamp for wild-type templates, which enriched the mutant products in PCR. During the melting analysis program, the fluorescein on the PNA sensor probe could undergo Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) with the Bodipy on the DNA anchor probe when both probes were annealed to the GNAS fragment. Measuring the FRET fluorescence along with temperature change revealed the association–dissociation status between the PNA sensor probe and the GNAS sequence. Further, plotting the negative derivative of the fluorescence over temperature (-dF/dT) against temperature generated melting peaks (as shown in Figure 2). The PCR products derived from mutant templates had a lower melting temperature (mutant Tm) than that from wild-type templates (wild-type Tm), so mutation can be identified through the existence of the mutant melting peak. Therefore, the assay can be completed in a single tube without the need for further manipulation.

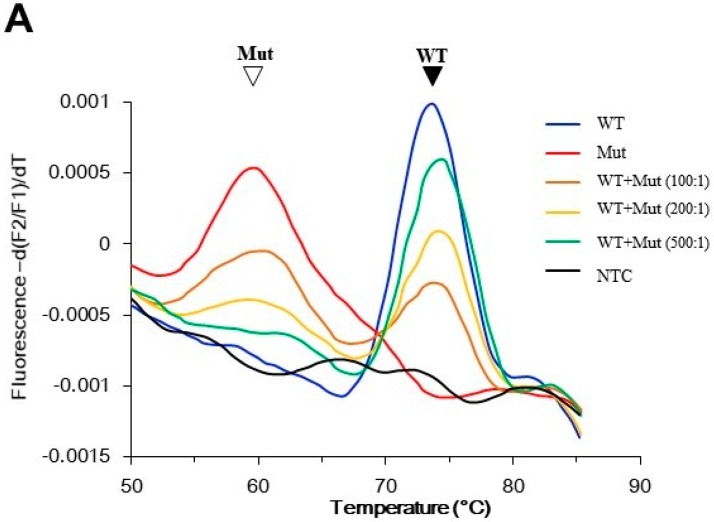

Figure 2.

Performance of the PNA probe assay. The assay generated melting peaks of the PNA/GNAS duplex. The PNA probe was perfectly matched with the wild-type GNAS, and hence had a peak at higher melting temperature (Tm) than the peak from the mismatched mutant GNAS. (A) Assay sensitivity was determined using control templates. The indicated ratio of mutant and wild-type plasmid DNA were mixed, and the mutant was detected by PNA probe assay. The filled arrowhead indicates the wild-type peak; the open arrowhead indicates the mutant peak; (B) Specificity of the assay. DNA (100 ng) from peripheral blood of 20 individuals without McCune–Albright syndrome/fibrous dysplasia (MAS/FD) were analyzed by the PNA probe assay. Only wild-type melting peaks were observed in these samples (green lines). The control reactions were conducted using either 10 pg wild-type plasmid DNA (blue line), 0.1 pg mutant plasmid DNA (red line), or no template (black line). Mut: mutant; NTC: no template control; WT: wild-type.

In a preliminary experiment using control templates, the wild-type DNA generated a peak at 75 °C, and the mutant DNA at 60 °C. Rare mutant alleles could reveal a mutant peak even in a 200-fold excess of wild-type alleles. In addition, the size of the mutant peak was positively correlated with the amount of mutant allele present. Hence, the assay was also semi-quantitative (Figure 2A). To demonstrate the assay specificity, blood samples from 20 healthy individuals were analyzed, and they all showed wild-type results (Figure 2B).

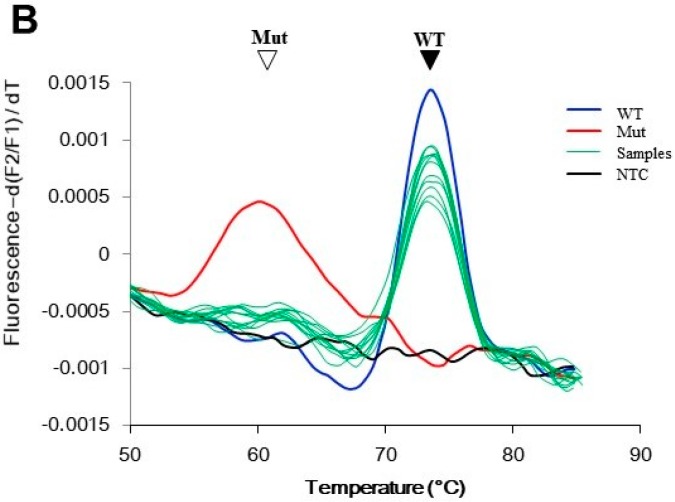

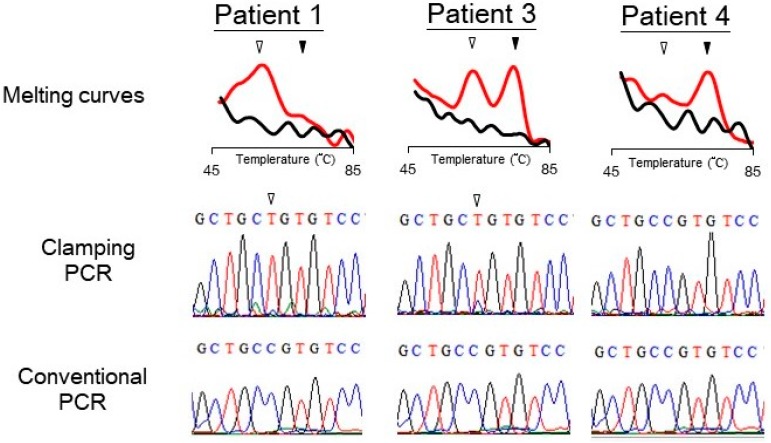

2.2. Genotypes Detected by the PNA Probe Assay

DNA samples from six patients with MAS/FD were analyzed for GNAS mutation by the PNA probe assay. The existence of mutation was determined through the melting peak profile. The PNA probe assay identified three patients with mutant GNAS (Table 1). To further demonstrate that the mutant melting peaks came from a disease-causing genotype, the PCR products were sent to Sanger sequencing analysis (shown as “clamping PCR” in Figure 3), which confirmed that these “expected mutants” had a point mutation at codon 201. For comparison, the samples were also amplified with conventional PCR without the PNA probe (conventional PCR). Sequencing of the conventional PCR products detected no mutation in the samples. Figure 3 shows the melting and sequencing results from three of the patients. In this figure, Patients 1 and 3, but not Patient 4, have an R201 mutation. Of the six samples, three (Patients 1–3) from patients with more severe symptoms (having both precocious puberty and FD) had a mutant GNAS. Clinical features of Patient 1 are shown in Supplemental Figure S1. The other three (Patient 4–6) from patients with mild symptoms (only having FD) showed wild-type results (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of six patients with MAS or FD.

| Patient | Sex | Age (Year) | PP 1 | Café-au-lait Spots | BFD 2 | GNAS Mutations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | twin A | Female | 0.39 | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | twin B | Female | 7.83 | + | − | + | + |

| 3 | Female | 5.28 | + | − | + | + | |

| 4 | Female | 11.95 | − | + | + | − | |

| 5 | Male | 12.05 | − | − | + | − | |

| 6 | Male | 6.25 | − | − | + | − |

1 PP: precocious puberty; 2 BFD: bone fibrous dysplasia.

Figure 3.

Typical results of detecting GNAS mutation in three patients with suspect McCune–Albright syndrome or fibrous dysplasia. The PNA probe assay generated melting curves of PCR products of the samples (top). The PCR products (marked as clamping PCR) were analyzed by Sanger sequencing (middle). For comparison, sequencing results from PCR products without using PNA probe (marked as conventional PCR) are also shown (bottom). Open arrowheads indicate the position of mutant bases or mutant peaks; filled arrowheads indicate the wild-type peaks.

3. Discussion

We have demonstrated the application of a single tube reaction using PNA as both PCR clamp and sensor probe for the detection of GNAS mutation. Unlike other reported methods that used PNA only for PCR clamping and needed to check the sequences of PCR products, our newly developed method couples PCR amplification, mutant enrichment, and mutation detection; hence, the assay can be accomplished in a single tube on a real-time PCR instrument without the need to go through several laborious procedures such as electrophoresis, hybridization, and enzymatic reaction.

The establishment of the PNA probe assay that can detect rare mutants in large amounts of wild-type DNA is difficult. The key point is clamping efficiency of the PNA probe in wild-type amplification, which reduces the amount of the wild-type products and enriches the mutant products during PCR. In the end of PCR, the wild-type products must be less than the mutant products; otherwise, it would mask the mutant peak in the melting analysis. To optimize the clamping efficiency, several factors are important: (1) The Tm of the PNA/wild-type duplex needs to be located between 65 °C and 75 °C; (2) The extension temperature in PCR needs to be around 10 °C lower than the wild-type Tm mentioned above, so that the PNA can clamp the wild-type amplification efficiently. For example, the extension temperature of our GNAS assay was 60 °C, which was 13 °C lower than the wild-type Tm at 73 °C; (3) The distance between the binding sites of the forward primer and the PNA probe must be greater than 90 nucleotides, which prevent the Taq DNA polymerase from running off the wild-type templates during temperature ramping (for detailed explanation, please refer to References [14,15]). (4) Asymmetric PCR can enhance the clamping efficiency. In our GNAS assay, the concentration of the forward primer was one fifth that of the reverse primer.

A major concern regarding the highly sensitive method is its specificity or false positive rate. Several facts reveal that our method is specific: Firstly, during the stage of method development, we did not find any mutant melting peaks in negative control using wild-type DNA (not shown); Secondly, we tested our method in twenty DNA samples from individuals without MAS/FD, which did not show any false positive result (Figure 2); Finally, the PCR products showing mutant melting peaks were sequenced to confirm the R201C mutation type (Figure 3). If the mutant melting peak came from a PCR error or other non-specific amplification, sequencing results would more likely be random variations, but not a specific mutant genotype. Note that the sequencing procedure in Figure 3 was not necessary for the assay. It was just for re-confirming the melting results.

In contrast to assay specificity, assay sensitivity is another important issue to evaluate. Although we have demonstrated that our assay had a comparable analytical sensitivity to some other PNA methods (see Reference [11] for an example), clinical sensitivity is not easy to measure on the MAS patients. One reason is that MAS is a rare disease, and it is very difficult to obtain a sufficient number of positive samples for statistical analysis. Another reason is that mutant-bearing cells in MAS/FD patients are unevenly distributed and highly mosaic, so the concentrations of mutant cells in the blood vary according to disease severity. Our results showing that only patients with severe symptoms (Patient 1–3) had detectable GNAS mutation confirm this observation. Since the assay is not a yes-or-no detection, the patients with mild symptoms (Patients 4–6) may also have GNAS mutation, but the level of released mutant cells in peripheral blood is too few to be detected. A previous studies had similar observation that only a part of the MAS/FD patients had detectable GNAS mutations in peripheral blood [11].

In the three MAS patients, two of them were a pair of monozygotic (MZ) twins (Patients 1 and 2, Table 1). The twins were almost concordant for MAS: both had precocious puberty and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, except lacking skin lesion. To our knowledge, no MZ twins have been reported to be completely concordant for MAS. Usually only one of the twins had typical MAS, while the other had no symptom or had only mild bone lesions or endocrinopathy [16,17,18]. The discrepancy may be due to the timing of postzygotic mutation that influences the distribution and phenotypic effect of mutant cells in the individual [19]. If this occurs at the embryonic stem cell stage or the inner cell mass stage, tissues from all three germ layers will be affected, and the MAS phenotypes emerge [20]. However, there might be some other inherited or environmental factors involved in the disease, making one or both MZ twins affected.

MAS/FD is a rare disease, so the test of GNAS mutation is not frequently performed in clinical laboratories. However, recent studies have shown that a pancreatic cancer lesion—intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)—bears GNAS mutation [21]. As the IPMN shows relatively benign characteristics and is not yet invasive cancer, diagnosis of IPMN increases the opportunity for curative therapies. In addition, GNAS mutations are also involved in hepatocellular carcinoma [22], kidney cancer [23], and colorectal tumors [24]. These findings will extend the applicability of our PNA probe assay. In addition, the PNA probe design can be modified in the detection of other somatic mutations, such as EGFR, KRAS, or BRAF mutations in many cancers.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Design of Probes and Primers

A forward primer and a reverse primer were designed to amplify GNAS fragments in exon 8. The sensor probe covering the variable region is a 16-mer PNA labeled with a fluorescein at the N-terminus (equivalent to the 5′-end of a DNA oligomer). The anchor probe is a 40-mer DNA labeled with fluorescent dye Bodipy 630/650 at the 3′-end via an OO linker. The design of the primers and the probes were according to a guideline described elsewhere [14]. PCR primers and the anchor probe were provided by TIB MOLBIOL (Berlin, Germany). PNA was provided by Applied Biosystems (Forster City, CA, USA). Sequences of primers and probes used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers and probes used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′ for DNA or N Terminal to C Terminal for PNA) | Length |

|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||

| Forward | AACTACTCCAGACCTTTGCTTTAGAT | 26 |

| Reverse | CAGCTGGTTATTCCAGAGGGAC | 22 |

| Probes | ||

| PNA sensor | (Fluorescein)-OO-CGCTGCCGTGTCCTGA | 16 |

| DNA anchor | TGGTGAGATCCATTGACCTCAATTTTGTTTCAGGACCTGC-(Bodipy630/650) | 40 |

4.2. Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (with approval number 101-0650A3). After obtaining informed consent, three patients with MAS and three with only FD of bone were screened for mutations of GNAS gene in blood. Patients with MAS have characteristics of precocious puberty, café au lait pigmentation, and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia of bone. Patients with only FD of bone do not show precocious puberty. Clinical characteristics of the three patients with MAS are summarized in Supplemental Materials Table S1.

4.3. Preparation of Template DNA

Sample DNA was extracted from 200-μL aliquots of whole blood (with EDTA as anticoagulant) using a QIAamp DNA-blood-mini kit (Qiagen). One hundred ng of the eluted DNA was used as PCR template. The control templates were plasmids with the wild-type or the mutant DNA fragment as an insert. Mutant plasmid DNA (0.1 pg) was added into different amounts of wild-type plasmid DNA, generating 100–500 fold wild-type backgrounds. The assay was performed under the conditions described below.

4.4. Detection of GNAS Mutation

The PCR mixture (20 μL) contained 50 mM Tris (pH 8.5), 3 mM MgCl2, 500 μg/mL BSA, 200 μM of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 0.2 μM forward, 1 μM reverse primers, 0.5 μM PNA sensor probe, 0.5 μM DNA anchor probe, 0.5 U Platinum Taq (ThermalFisher Scientific), and templates. The assay was performed on a LightCycler 1.5 or 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The thermal program contained an amplification step and a melting step. The amplification step started with a 3-min denaturation at 95 °C, then ran for 55 cycles as follows: 95 °C for 5 s, 53 °C for 3 s, and 60 °C for 20 s. The melting step was performed after a 30 s denaturation at 95 °C and then decreasing the temperature to 40 °C at ramp rate 0.7 °C/s. The fluorescent signal was detected in channel F2 for the BODIPY labeled probes. To confirm results and determine specific mutation types, PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, eluted, and then sequenced by an automated DNA sequencer.

5. Conclusions

Our study indicated that PNA was not only a good clamp in PCR for enriching rare mutants but also a superior sensor probe for genotyping. Both features make it possible to create a simple and sensitive method to detect trace amounts of GNAS mutants in a large amount of wild-type DNA. This method has great potential for the screening of diseases with GNAS mutation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grant CMRPG4C0011 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. Table S1 Clinical and laboratory findings of three patients with McCune-Albright syndrome. Figure S1 Features of Patient 1. Figure S2 Melting curves of all patients.

Author Contributions

F.-S.L. designed the experiments, collected samples, made the clinical implication of the data, and prepared part of the manuscript. T.-L.C. conducted the experiments and prepared the figures in the manuscript. C.-C.C. designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Not Available.

References

- 1.Schwindinger W.F., Francomano C.A., Levine M.A. Identification of a mutation in the gene encoding the alpha subunit of the stimulatory G protein of adenylyl cyclase in McCune-Albright syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:5152–5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shenker A., Weinstein L.S., Sweet D.E., Spiegel A.M. An activating Gs alpha mutation is present in fibrous dysplasia of bone in the McCune-Albright syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994;79:750–755. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.3.8077356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein L.S., Shenker A., Gejman P.V., Merino M.J., Friedman E., Spiegel A.M. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:1688–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112123252403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiegel A.M., Weinstein L.S., Shenker A. Abnormalities in G protein-coupled signal transduction pathways in human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 1993;92:1119–1125. doi: 10.1172/JCI116680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannon T.S., Noonan K., Steinmetz R., Eugster E.A., Levine M.A., Pescovitz O.H. Is McCune-Albright syndrome overlooked in subjects with fibrous dysplasia of bone? J. Pediatr. 2003;142:532–538. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim I.S., Kim E.R., Nam H.J., Chin M.O., Moon Y.H., Oh M.R., Yeo U.C., Song S.M., Kim J.S., Uhm M.R., et al. Activating mutation of GS alpha in McCune-Albright syndrome causes skin pigmentation by tyrosinase gene activation on affected melanocytes. Horm. Res. 1999;52:235–240. doi: 10.1159/000023467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Candeliere G.A., Roughley P.J., Glorieux F.H. Polymerase chain reaction-based technique for the selective enrichment and analysis of mosaic arg201 mutations in G alpha s from patients with fibrous dysplasia of bone. Bone. 1997;21:201–206. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riminucci M., Liu B., Corsi A., Shenker A., Spiegel A.M., Robey P.G., Bianco P. The histopathology of fibrous dysplasia of bone in patients with activating mutations of the Gs alpha gene: Site-specific patterns and recurrent histological hallmarks. J. Pathol. 1999;187:249–258. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199901)187:2<249::AID-PATH222>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyger E.M., Krevolin M.D., Powell M.J. Detection of the hereditary hemochromatosis gene mutation by real-time fluorescence polymerase chain reaction and peptide nucleic acid clamping. Anal. Biochem. 1998;260:142–148. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianco P., Riminucci M., Majolagbe A., Kuznetsov S.A., Collins M.T., Mankani M.H., Corsi A., Bone H.G., Wientroub S., Spiegel A.M., et al. Mutations of the GNAS1 gene, stromal cell dysfunction, and osteomalacic changes in non-McCune-Albright fibrous dysplasia of bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000;15:120–128. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalfa N., Philibert P., Audran F., Ecochard A., Hannon T., Lumbroso S., Sultan C. Searching for somatic mutations in McCune-Albright syndrome: A comparative study of the peptidic nucleic acid versus the nested PCR method based on 148 DNA samples. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2006;155:839–843. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lietman S.A., Ding C., Levine M.A. A highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction method detects activating mutations of the GNAS gene in peripheral blood cells in McCune-Albright syndrome or isolated fibrous dysplasia. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2005;87:2489–2494. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karadag A., Riminucci M., Bianco P., Cherman N., Kuznetsov S.A., Nguyen N., Collins M.T., Robey P.G., Fisher L.W. A novel technique based on a PNA hybridization probe and FRET principle for quantification of mutant genotype in fibrous dysplasia/McCune-Albright syndrome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiou C.C., Luo J.D., Chen T.L. Single-tube reaction using peptide nucleic acid as both PCR clamp and sensor probe for the detection of rare mutations. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2604–2612. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo J.D., Chan E.C., Shih C.L., Chen T.L., Liang Y., Hwang T.L., Chiou C.C. Detection of rare mutant K-ras DNA in a single-tube reaction using peptide nucleic acid as both PCR clamp and sensor probe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemli L. Fibrous dysplasia of bone. Report of female monozygotic twins with and without the McCune-Albright syndrome. J. Pediatr. 1977;91:947–949. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(77)80898-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukazawa T., Ohtawara H., Motozumi H., Senoo I., Hayashibara H., Hanaki K., Ohzeki T. McCune-Albright syndrome in one of monozygotic twins. J. Jpn. Pediatr. Soc. 1990;94:1913. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endo M., Yamada Y., Matsuura N., Niikawa N. Monozygotic twins discordant for the major signs of McCune-Albright syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1991;41:216–220. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320410217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell I.M., Shaw C.A., Stankiewicz P., Lupski J.R. Somatic mosaicism: Implications for disease and transmission genetics. Trends Genet. 2015;31:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumitrescu C.E., Collins M.T. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J., Matthaei H., Maitra A., Dal Molin M., Wood L.D., Eshleman J.R., Goggins M., Canto M.I., Schulick R.D., Edil B.H., et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:92ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nault J.C., Fabre M., Couchy G., Pilati C., Jeannot E., Tran Van Nhieu J., Saint-Paul M.C., De Muret A., Redon M.J., Buffet C., et al. GNAS-activating mutations define a rare subgroup of inflammatory liver tumors characterized by STAT3 activation. J. Hepatol. 2012;56:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalfa N., Lumbroso S., Boulle N., Guiter J., Soustelle L., Costa P., Chapuis H., Baldet P., Sultan C. Activating mutations of Gsalpha in kidney cancer. J. Urol. 2006;176:891–895. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fecteau R.E., Lutterbaugh J., Markowitz S.D., Willis J., Guda K. GNAS mutations identify a set of right-sided, RAS mutant, villous colon cancers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.