Abstract

We report a site-selective cysteine-cyclooctyne conjugation reaction between a seven-residue peptide tag (DBCO-tag, Leu-Cys-Tyr-Pro-Trp-Val-Tyr), at the N or C-terminus of a peptide or protein, and various aza-dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) reagents. Compared to a cysteine peptide control, the DBCO-tag increases the rate of the thiol-yne reaction by 220-fold, enabling selective conjugation of DBCO-tag to DBCO-linked fluorescent probes, affinity tags, and cytotoxic drug molecules. Fusion of DBCO-tag with the protein of interest enables regioselective cysteine modification on proteins that contain multiple endogenous cysteines; these examples include green fluorescent protein and trastuzumab antibody. This study demonstrates short peptide tags could aid in accelerating bond forming reactions that are often slow to non-existent in water.

Keywords: bioconjugation, cysteine-cyclooctyne reaction, site-selective, protein modification, sequence-selective

Site-selective protein modification is a powerful approach to precisely manipulate protein structure and function.[1–3] However, it may be challenging to modify one amino acid side-chain among many others with similar reactivity in a protein. Bioorthogonal reactions with paired functional groups have been developed to solve this selectivity challenge.[4,5] One such approach (Figure 1a) introduces azides that react with cyclooctyne reagents through strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC).[6] SPAAC has been widely used for selectively labelling cell surface glycans[7,8], membrane proteins[9], and antibodies[10,11]. Azides are not genetically encoded and therefore need to be introduced into proteins via metabolic glycoengineering[7,8], incorporation of unnatural amino acids[9], or enzyme-catalyzed reactions[11].

Figure 1.

Protein modification with dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) reagents. (a) Proteins with azides can react with DBCO reagents via strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) reactions; thiol-modified side products can be generated with cysteine-containing proteins. (b) Previous thiol-yne conjugations using DBCO reagents are not regioselective and generate mixtures of products with proteins containing multiple cysteines. (c) The DBCO-tag enables site-selective thiol-yne reaction that modifies the DBCO-tag cysteine in the presence of other competing cysteine residues on the same protein.

Thiol-yne coupling is an emerging “click” reaction and has been extensively used in polymer and material science.[12,13] Thiol-yne reactions often proceed through a radical process under UV irradiation. Alternatively, thiolates can react with electrophilic alkynes through a nucleophilic addition process. Several examples of peptide and protein modification using the thiol-yne reaction have been reported,[14–19] and cysteine-DBCO reaction was observed as a side reaction when using DBCO reagents to label proteins.[20] However, even though Ovaa and Mootz showed that regioselectivity could be achieved when the cysteine and alkyne are in proximity driven by enzyme-substrate recognition in two reports,[21,22] most of these thiol-yne reactions are not regioselective and cannot distinguish different cysteine residues (Figure 1b).

Tuning the reactivity of peptides has led to efficient and selective catalysts[23–25] and tags[26–33]. In particular, site-selective reactions enabled by unique amino acid sequences have been discovered, including tetracysteine tag that reacts with the biarsenical fluorescent dyes,[26,27] tetraserine tag that reacts with rhodamine-derived bisboronic acid,[28] sequence-specific 2-cyanobenzothiazole ligation,[29] p- (chloromethyl)benzamide-reactive peptide[30] and the the π-clamp-mediated cysteine perfluoroarylation.[31–33] In light of these findings, we envisioned that a designer peptide sequence could be used to achieve site-selective cysteine bioconjugation by thiol-yne reaction. We focused on the thiol-yne reaction because the important DBCO reagents are widely used and commercial available. Here we report the discovery of a genetically encoded peptide tag (DBCO-tag) that sequence-selectively reacts with DBCO reagents through cysteine-cyclooctyne conjugation reaction (Figure 1c).

We commenced our study with a library selection approach to identify peptides that increase the rate of the cysteine-cyclooctyne conjugation reaction (Section 2 in supporting information). We used split-pool synthesis to create a one-bead-one-compound peptide library (XCXXXXX-GLLKG, X is any natural amino acid except Cys, Arg, Ile, Asn, and Gln) with random amino acids flanking the cysteine residue (Figure S1). Each bead in the library has a single peptide species, enabling each peptide to react with a probe without interference from other library members. The GLLKG sequence was used to promote retention of library members on the column for de novo sequencing of hits using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).[34] The library was reacted with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1), and the beads containing reacted species were isolated by fluorescence-activated bead sorting (FABS) after staining with streptavidin-fluorophore (Figure S2). Peptide hits on the isolated beads were cleaved and then sequenced by LC-MS/MS. The selection yielded 40 putative hits (Table S2) from which we found one sequence (LCYPFVY-GLLKG, referred to as DBCO-16) to be particularly reactive towards DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (Figure S5).

Alanine mutations of DBCO-16 revealed that the phenylalanine at position 5 was critical for the reactivity of DBCO-16 (Figure S6). We then mutated Phe5 of DBCO-16 to other natural amino acids except cysteine and found a more reactive sequence with the phenylalanine mutated to tryptophan (Figure S7). The mutation led to a seven-residue sequence (LCYPWVY), hereafter referred to as the DBCO-tag. Peptide P1 (LCYPWVYGLLKG) with DBCO-tag at the N-terminus readily conjugated to DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) with a rate constant of 0.81 ± 0.02 M−1S−1 in pH 8.0 phosphate buffer at 37 °C (entry 1 in Table 2, and Figure S8).

Table 2.

Reaction rates and sequences of peptides used in mechanistic studies.

|

All peptides contain N-terminal free amino group and C-terminal amide, except P9 is N-terminal acylated.

Detailed reaction conditions are in the SI. Errors are from linear fitting of the rate equation (see Section 5 of the SI for detailed method for kinetics studies).

The DBCO-tag can function at different positions in a peptide chain, while the N-terminus position appears to be optimal. Model peptides with DBCO-tag at the N-terminus (peptide P1), the C-terminus (peptide P3) and the middle (peptide P4) of the peptide chain were all reactive toward DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (Table S3, Figures S16 and S17). The reaction rate constant of the slowest variant (P4) was still 15-fold higher than the control peptide P2, indicating the potential flexibility of incorporating the DBCO-tag into the peptide or protein of interest.

The substrate scope of the DBCO-tag-mediated conjugation and the regioselectivity on the alkyne of DBCO reagents were investigated. Peptide P1 readily reacted with a diverse set of DBCO-linked probes bearing biotin (1), polyethylene glycol (2), fluorophores (3 and 4), and a small molecule toxin (5) (Table 1, Figures S18 and S19). Possibly due to the nature of the library selection, DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) was the most reactive reagent. Reacting P1 with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) produced conjugate P1–1, which appeared as two co-eluting isomers generated from addition of the cysteine thiol to either one of the two alkyne carbons when analyzed by LC-MS. Fortunately, treating the reaction product with 1M NaOH cleaved the C-S bond and generated two separate eluting species with the same mass (Figure S20), indicating that the cysteine thiol of the DBCO-tag does not selectively add to the alkyne moiety on DBCO reagents.

Table 1.

Peptide P1 with DBCO-tag reacted with various DBCO reagents efficiently.a

|

Yields shown were obtained from liquid chromatography-ESI-QTOF mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of the crude reactions. Because P1 was the limiting reagent and no peptidic side products were generated, the conversion of P1 equals the reaction yield. Reaction conditions: 0.5 mM P1, 1.5 mM probe 1-5, 2 mM DTT, 200 mM phosphate, pH 8.0, 37°C, 4h. See Figures S18 and S19 for LC-MS chromatograms and reaction details. *4 mM DTT, 16 h.

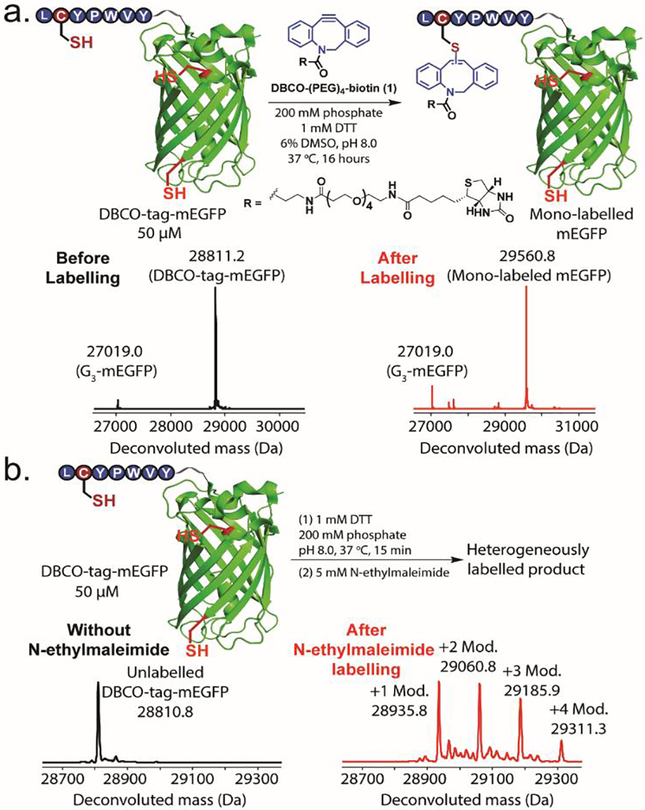

We then used the DBCO-tag for site-selective protein modification. First, we incorporated the DBCO-tag to the N-terminus of monomeric enhanced green fluorescent protein (mEGFP) by the use of sortagging reaction to get DBCO-tag-mEGFP (Figure S21). DBCO-tag-mEGFP reacted with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) to generate the desired mono-labelled mEGFP product in 80% yield while no multi-lablelled product was formed, as shown in the LC-MS analysis of the crude reaction mixture (Figure 2a). In contrast, mEGFP without DBCO-tag showed no reaction with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) under the same reaction conditions, suggesting that the two surface-exposed cysteine residues in mEGFP did not react with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) (Figure S22). Furthermore, reacting DBCO-tag-mEGFP with N-ethylmaleimide led to a heterogeneous mixture of products (Figure 2b). While there are only three cysteines in DBCO-tag-mEGFP, we observed modified proteins with one, two, three or even four modifications, indicating N-ethylmaleimide is neither chemoselective nor regioselective in this case.

Figure 2.

DBCO-tag enabled site-selective mEGFP labelling. (a) Site-selective conjugation between DBCO-tag-mEGFP and DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1). A small amount of G3-mEGFP was present in the starting material and reaction mixture due to incomplete sortagging reaction. Reaction conditions: 50 μM DBCO-tag-mEGFP, 1 mM DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1), 0.2 M phosphate, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0, 6 % DMSO, 37°C, 16 hours. (b) N-ethylmaleimide protein labelling resulted in heterogeneous products. Reaction conditions: 50 μM DBCO-tag-mEGFP, 0.2 M phosphate, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0, 37°C, 15 minutes, then add 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide to the reduced protein and reacted at 37°C for 1 hour.

Next, the DBCO-tag was incorporated into a monoclonal antibody for site-selective modification. Several groups have reported using azide-containing antibodies for site-selective conjugation to DBCO reagents.[11,35,36] However, genetic code expansion or glycoengineering are required to produce azide-containing antibodies. The DBCO tag is composed of natural amino acids; therefore, we reasoned that the DBCO-tag-mediated conjugation could be a complementary and potentially advantageous approach to azide-based methods for selectively conjugating DBCO reagents to antibodies. The DBCO-tag was readily fused onto the C-terminus of the heavy chains of the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab by mutagenesis (Section 4 in Supporting Information). The expressed and purified DBCO-tag-trastuzumab site-selectively reacted with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (1) under reducing conditions to generate 90% of heavy-chain mono-labeled product as determined by LC-MS analysis (Figure 3a). The eight free cysteines generated from reduced intrachain disulfides remained intact during the reaction. The control reaction using native trastuzumab produced minimal product under the same reaction conditions (Figure S23). As a comparison, N-ethylmaleimide indiscriminately labeled all 10 cysteines (2 DBCO-tag cysteines and 8 intrachain cysteines) on DBCO-tag-trastuzumab under reducing conditions (Figure S31). To evaluate whether the protein function was impaired by the labelling reaction, we measured the binding affinity of the site-selectively biotinylated trastuzumab to HER2 protein. The labelled trastuzumab showed full binding affinity to recombinant HER2 protein in an Octet BioLayer Interferometry assay (Kd = 39 ± 2 pM, consistent with the previously measured binding affinity of native trastuzumab[31], Figure 3b and S24).

Figure 3.

DBCO-tag enabled site-selective antibody labelling without impairing the protein binding function. (a) Site-selective antibody modification using DBCO-tag. The DBCO-tag was placed at the C-terminus of antibody heavy chain. A small amount of C-terminal truncation (minus Lys-Gly) was present in the starting material, and was labeled as ‘-KG’. Reaction conditions: 100 μM DBCO-tag-trastuzumab, 2 mM DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin, 0.2 M phosphate, 10 mM DTT, pH 8.0, 10% DMSO, 37°C, 4 hours. (b) Site-selectively biotinylated trastuzumab retains its binding affinity to recombinant HER2 in Octet BioLayer Interferometry assay. 20 μM site-selectively biotinylated DBCO-tag-trastuzumab was immobilized on the streptavidin biosensors and sampled with serially diluted concentrations of recombinant HER2 (concentrations shown next to each sensorgram); see Figure S24 for fitting and data analysis.

One potential advantage of DBCO-tag mediated conjugation reaction is the stability of the thiol enol ether products. The generated linkage was stable to exogenous thiols at physiological pH, in stark contrast to the corresponding cysteine-maleimide conjugate. We reacted P1 with N-ethylmaleimide to generate P1–7 as a comparison with the conjugate P1–1 for their stability against the exogenous thiol glutathione at pH 7.4 and 37°C. LC-MS analysis indicated that the cysteine-cyclooctyne conjugate P1–1 was intact after 4 days (Figures S25 and S26). In contrast, the thiosuccinimide linkage of P1–7 was not stable and underwent hydrolysis and maleimide elimination[37], leaving less than 14% of intact P1–7 after 4 days (Figures S25 and S26). The high stability of the cysteine-DBCO conjugate underpinned the potential usage of the reaction in biological applications such as drug conjugation.

We found DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin is inert to our previously reported π-clamp (Phe-Cys-Pro-Phe)[31]. This enables, for the first time, a site-selective labeling of three unprotected cysteine peptides in a single solution using three different reagents (Figure S33). We sequentially added DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin, a perfluoroaryl reagent, and N-ethylmaleimide into a mixture containing equal concentrations of the DBCO-tag peptide P1, a π-clamp peptide, and the cysteine peptide control P2. We observed selective and almost quantitative labeling at all three steps; the DBCO-tag peptide was modified with DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin, the π-clamp peptide was conjugated to the perfluoroaryl reagent, and the control peptide P2 was labeled with maleimide. Order of reagent addition was critical to achieving this outcome—if the perfluoroaryl reagent were added first, it would react with both the π-clamp and the DBCO tag (Figure S44); if the maleimide were added first, it would react with all three peptides. Although these three conjugation chemistries (i.e., π-clamp, DBCO-tag, and maleimide) are not orthogonal, the outcome of the sequential labeling is the same as that of one-pot orthogonal conjugation. We expect the DBCO-tag together with the π-clamp will provide new strategies for site-selective multiple labeling of proteins.

Mutation studies were carried out to understand what residues are important for the reactivity of the DBCO-tag. Every residue within the sequence was found to be important, as mutating any one of the residues to glycine decreased the reactivity towards DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin (entries 2 to 7 in Table 2, and Figures S9–S14). An all-glycine control peptide P2 was minimally reactive towards DBCO-(PEG)4-biotin with a rate constant that was about 220-fold slower than P1 (entry 8 in Table 2 and Figure S15). Compared to the DBCO-tag, an all-alanine peptide P7 and a peptide P8 with Trp-5 are 213-fold and 88-fold slower, respectively (entries 9 and 10 in Table 2, and Figures S41a and S41b). Acylation of the N-terminus of P1 led to a slightly higher rate constant of 0.91 ± 0.02 M−1s−1 (entry 11 in Table 2 and Figure S41c), indicating that the N-terminal amine is not a critical factor contributing to the rate enhancement of the DBCO-tag. Collectively, these mutation studies are suggestive of a role for sequence-specific recognition between the DBCO-tag and DBCO reagents.

To further distinguish between general hydrophobic cage[38] and sequence-specific hydrophobic recognition mechanisms, we looked for a possible relationship between peptide hydrophobicity and reactivity among the putative hits from our library selection (Table S2). A plot of reaction yield vs. hydrophobicity (Figure S34) revealed that reactive sequences occurred across a range of hydrophobicity values, and that some of the most hydrophobic sequences were unreactive. Additionally, we found DBCO-tag peptide P1 to be unreactive towards another hydrophobic, commercially available cyclooctyne, BCN-OH ((1R,8S,9s)-Bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-yn-9-ylmethanol) (Figure S42). Taken together, these data suggest that while hydrophobic interaction may to some extent be necessary for the DBCO-tag-mediated conjugation, it alone is insufficient to appreciably accelerate a thiol-yne reaction in water; some degree of sequence-specific recognition between the DBCO tag and DBCO is required.

To further understand the mechanism of the developed reaction, we investigated if the DBCO-tag-mediated cysteine-cyclooctyne reaction might proceed as radical process. We carried out the reaction under visible light, dark conditions or in the presence of potential radical scavenger ascorbate. Similar reaction rate constants were observed for all these conditions (entry 1 in Table 2 and Figures S31–S32), indicating that radicals may not be involved and the reaction might proceed through a nucleophilic addition process.

Because thiolate is more nucleophilic than thiol, we investigated whether the enhanced reactivity of DBCO-tag is due to the decreased pKa of its cysteine thiol. We found that the pKa of cysteine thiol in DBCO-tag peptide P1 (pKa = 7.9 ± 0.1, Figure S35) was about 0.5 units lower than that of the all-glycine mutant P2 (pKa = 8.43 ± 0.06, Figure S39). However, reacting a mixture of equal concentrations of P1 and P2 at pH 9.88 with DBCO probe 1 only led to quantitative and selective labeling of P1 (Figure S40). At this pH, more than 95% of cysteine species should be thiolate, indicating that the decreased pKa of the DBCO-tag is not the major reason for the enhanced reactivity towards DBCO reagents.

In summary, we discovered a cysteine-containing peptide tag (DBCO-tag) that selectively reacts with aza-dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) probe bearing a wide range of cargoes to form a linkage stable to exogenous thiols. This work expanded the idea of promoting otherwise sluggish reactions using short peptide sequences. DBCO-tag enabled site-selective modification of mEGFP and trastuzumab antibody that contain multiple endogenous cysteines, highlighting its potential for selectively labelling other cysteine-containing proteins that are a challenge to modify using traditional alkylation reagents. The reaction rate of DBCO-tag-mediated conjugation is influenced by both the functional group in the DBCO probe and the protein sequence to which the DBCO-tag is fused to. This observation along with the mutagenesis study and salt effect, suggest the local environment at the reaction interface is important for the reactivity of the DBCO-tag. We anticipate this DBCO-tag provides a convenient tool for site-selective protein modification as there are many commercially available DBCO-probes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by NIH (Award No. GM110535) and DARPA (Award No. 023504–001) for B.L.P. C.Z. is a recipient of George Büchi Summer Research Fellowship, Koch Graduate Fellowship in Cancer Research from MIT, and Bristol-Myers Squibb Fellowship in Synthetic Organic Chemistry.

References

- [1].Carrico IS, Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37, 1423–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Krall N, da Cruz FP, Boutureira O, Bernardes GJL, Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Spicer CD, Davis BG, Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2001, 40, 2004–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2009, 48, 6974–6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jewett JC, Bertozzi CR, Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39, 1272–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15046–15047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Laughlin ST, Baskin JM, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR, Science 2008, 320, 664–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beatty KE, Fisk JD, Smart BP, Lu YY, Szychowski J, Hangauer MJ, Baskin JM, Bertozzi CR, Tirrell DA, ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 2092–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Agarwal P, Bertozzi CR, Bioconjug. Chem 2015, 26, 176–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Van Geel R, Wijdeven MA, Heesbeen R, Verkade JMM, Wasiel AA, Van Berkel SS, Van Delft FL, Bioconjug. Chem 2015, 26, 2233–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lowe AB, Polym 2014, 55, 5517–5549. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hoogenboom R, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2010, 49, 3415–3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lo Conte M, Staderini S, Marra A, Sanchez-Navarro M, Davis BG, Dondoni A, Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 11086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lo Conte M, Pacifico S, Chambery A, Marra A, Dondoni A, J. Org. Chem 2010, 75, 4644–4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shiu HY, Chan TC, Ho CM, Liu Y, Wong MK, Che CM, Chem. - A Eur. J 2009, 15, 3839–3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Koniev O, Leriche G, Nothisen M, Remy JS, Strub JM, Schaeffer-Reiss C, Van Dorsselaer A, Baati R, Wagner A, Bioconjug. Chem 2014, 25, 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Griebenow N, Dilmaç AM, Greven S, Bräse S, Bioconjug. Chem 2016, 27, 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li Y, Pan M, Li Y, Huang Y, Guo Q, Org. Biomol. Chem 2013, 11, 2624–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Van Geel R, Pruijn GJM, Van Delft FL, Boelens WC, Bioconjug. Chem 2012, 23, 392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sommer S, Weikart ND, Linne U, Mootz HD, Bioorganic Med. Chem 2013, 21, 2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ekkebus R, Van Kasteren SI, Kulathu Y, Scholten A, Berlin I, Geurink PP, De Jong A, Goerdayal S, Neefjes J, Heck AJR, et al. , J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 2867–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tanaka F, Barbas CF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 3510–3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Giuliano MW, Miller SJ, in Top. Curr. Chem, Springer, Cham, 2015, pp. 157–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lewandowski B, Wennemers H, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2014, 22, 40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Griffin BA, Adams SR, Tsien RY, Science 1998, 281, 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, Yao Y, Llopis J, Tsien RY, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 6063–6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Halo TL, Appelbaum J, Hobert EM, Balkin DM, Schepartz A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 438–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ramil CP, An P, Yu Z, Lin Q, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5499–5502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kawakami T, Ogawa K, Goshima N, Natsume T, Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 1671–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang C, Welborn M, Zhu T, Yang NJ, Santos MS, Van Voorhis T, Pentelute BL, Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dai P, Zhang C, Welborn M, Shepherd JJ, Zhu T, Van Voorhis T, Pentelute BL, ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dai P, Williams JK, Zhang C, Welborn M, Shepherd JJ, Zhu T, Van Voorhis T, Hong M, Pentelute BL, Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vinogradov AA, Gates ZP, Zhang C, Quartararo AJ, Halloran KH, Pentelute BL, ACS Comb. Sci 2017, 19, 694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zimmerman ES, Heibeck TH, Gill A, Li X, Murray CJ, Madlansacay MR, Tran C, Uter NT, Yin G, Rivers PJ, et al. , Bioconjug. Chem 2014, 25, 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wu Y, Zhu H, Zhang B, Liu F, Chen J, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Wu L, Si L, et al. , Bioconjug. Chem 2016, 27, 2460–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Baldwin AD, Kiick KL, Bioconjug. Chem 2011, 22, 1946–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Breslow R, Acc. Chem. Res 1991, 24, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.