Abstract

Although the emotional disorders (EDs) have achieved favorable reliability in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), accumulating evidence continues to underscore limitations in ED diagnostic validity. In particular, taxometric, comorbidity, and other descriptive psychopathology studies of transdiagnostic phenotypes studies suggest that the EDs may be best conceptualized as dimensional entities that are more similar than different. Despite optimism that the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) would constitute a meaningful shift toward dimensional ED assessment and diagnosis, most changes contribute little movement in that direction. In the present report, we summarize past and anticipate persisting (i.e., in DSM-5) limitations of a purely categorical approach to ED diagnosis. We then review our alternative dimensional-categorical profile approach to ED assessment and classification, including preliminary evidence in support of its validity and presentation of two ED profile case examples using our newly developed Multidimensional Emotional Disorder Inventory. We end by discussing the transdiagnostic treatment implications of our profile approach to ED classification and directions for future research.

Keywords: emotional disorders, internalizing disorders, diagnostic reliability, diagnostic validity, categorical versus dimensional classification, hybrid dimensional-categorical classification, multidimensional emotional disorder inventory, transdiagnostic dimensions, transdiagnostic treatments

The emotional disorders (EDs, i.e., anxiety, mood, somatic, obsessive, trauma, and related disorders) have undergone extensive changes across editions of the DSM (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) in an attempt to improve diagnostic reliability and validity. Although there has been undeniable progress in regard to diagnostic reliability, considerable criticism persists over the validity of the primarily categorical approach to ED diagnosis that is used in DSM. In particular, DSM-5 neglected to advance a substantive dimensional approach to ED assessment and diagnosis. In contrast, hybrid dimensional-categorical approaches to classification have been increasingly discussed (Maser et al., 2009) and even integrated as an alternative classification scheme for the personality disorders in DSM-5 (see APA, 2013, Emerging Measures and Models, pp. 761–781). Accordingly, in the present report we aim to: (1) summarize past and persisting limitations to categorical ED diagnosis, (2) review an alternative dimensional-categorical profile approach to ED classification, and (3) introduce a new assessment instrument that is being developed with the specific intent of a profile-based ED assessment.

Reliability and Validity of the Emotional Disorders

The most drastic revision to DSM occurred when disorders were first distinguished from one another on the basis of polythetic criteria/symptom sets in DSM-III (APA, 1980). In addition to promoting disorder-specific psychopathology and treatment outcome research, this “splitting” of criteria/symptoms into different categories also allowed for the development of structured and semi-structured diagnostic interviews (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990; Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule, Di Nardo & Barlow, 1988). The advancement of such assessment methods has allowed favorable ED diagnostic reliability to be much improved over the past two decades (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001; Di Nardo, Moras, Barlow, Rapee, & Brown, 1993; Janca, Burke, Issac, & Burke, 1995; Williams et al., 1992). Despite this progress, however, two forms of unreliability have been perpetuated by DSM’s categorical-splitting approach to ED classification: unreliability due to disagreements in (1) threshold (i.e., deciding if a disorder is causing clinically significant interference or distress), and (2) differential diagnosis/diagnostic overlap (i.e., deciding if a symptom is due to disorder A, disorder B, or both).

These forms of unreliability are particularly concerning because they may be the consequence of limitations related to the construct validity of DSM EDs. For example, taxometric analyses have been used to show that DSM-IV social phobia (Kollman et al., 2006), major depression (Ruscio & Ruscio, 2002), posttraumatic stress disorder (Ruscio, Ruscio, & Keane, 2002), generalized anxiety disorder (Ruscio, Borkovec, & Ruscio, 2001), and somatic symptom disorders (Jasper, Hiller, Rist, Bailer, Witthoft, 2012) may be best operationalized as dimensional constructs rather than diagnostic categories defined by DSM thresholds. Findings related to the ubiquity of not otherwise specified diagnoses (Widiger & Samuel, 2005) also support the abandonment of diagnostic thresholds; individuals who fall “one symptom short” of a diagnosis are not necessarily meaningfully different from those with the minimum number of criteria needed to assign a disorder (Pincus, McQueen, & Elinson, 2003). Regarding diagnostic overlap, high rates of ED comorbidity (Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005) have led researchers to hypothesize that DSM may excessively discriminate symptoms that actually reflect transdiagnostic (i.e., cross-cutting) phenotypes (e.g., Andrews, 1996). Along with evidence showing the remission of multiple disorders via a single disorder-specific treatment (Brown, Antony, & Barlow, 1995; Hudson & Pope, 1990), it has become increasingly reasonable to presume that DSM EDs are more similar than different (Andrews, 1996; Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis, & Ellard, 2013).

Changes to the Emotional Disorders in DSM-5

In the years leading up to its release, the aforementioned limitations led many to anticipate that DSM-5 would constitute a meaningful shift away from categorical classification toward a more dimensional view of mental disorders. Most changes introduced in DSM-5, however, contribute little movement in that direction. Instead, changes to the EDs in DSM-5 have taken two contrasting approaches. Structurally, several EDs have been reorganized to highlight commonalities in etiology, symptom expression, and comorbidity. Coinciding with this effort, however, DSM-5 also reflects a continuation of the categorical-splitting of disorders that has been observed since DSM-III. Table 1 provides a summary of the changes that were made to the EDs in DSM-5.

Table 1.

Structure and specifiers of the DSM-5 Emotional Disorders

| DSM-5 Disorder | Changes from DSM-IV |

|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders | |

|

|

|

| Panic disorder | No longer diagnosed with or without agoraphobia Cued panic attacks due to other any other DSM-5 disorder now captured using panic attack specifier |

| Agoraphobia | Classified separately from panic disorder |

| Separation anxiety disorder | No longer classified in the childhood disorders section |

| Selective mutism | No longer classified in the childhood disorders section |

| Social anxiety disorder | New specifier: performance only |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | |

| Specific phobia | |

| Substance/medication induced anxiety disorder | |

| Anxiety disorder due to another medical condition | |

| Other specified anxiety disorder | New disorder split from DSM-IV anxiety disorder NOS |

| Unspecified anxiety disorder | New disorder split from DSM-IV anxiety disorder NOS |

| Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders (OCRDs) | New section |

|

|

|

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | No longer classified in the anxiety disorders section New specifiers: good/fair insight; absent insight/delusional beliefs; tic-related |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | No longer classified in the somatoform disorders section New specifiers: muscle dysmorphia; good/fair insight; poor insight; absent insight/delusional beliefs |

| Trichotillomania | No longer classified in the impulse-control disorders section |

| Excoriation | No longer classified in the impulse-control disorders section |

| Hoarding disorder | New disorder (previously subsumed under DSM-IV obsessive-compulsive disorder) |

| Substance/medication induced OCRD | New disorder |

| OCRD due to another medical condition | New disorder |

| Other specified OCRD | New disorder |

| Unspecified OCRD | New disorder |

| Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders (TSRDs) | New section |

|

|

|

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | No longer classified in the anxiety disorders section New specifier: dissociative symptoms |

| Adjustment disorders | No longer classified in the adjustment disorders section (section eliminated) |

| Reactive attachment disorder | No longer classified in the childhood disorders section New specifiers: persistence; severity |

| Disinhibited social engagement disorder | No longer classified in the childhood disorders section New specifiers: persistence; severity |

| Acute Stress Disorder | No longer classified in the anxiety disorders section |

| Other-specified TSRD | New disorder |

| Unspecified TSRD | New disorder |

| Depressive Disorders | New section split from DSM-IV mood disorders section New specifiers: anxious distress and severity; mixed features |

|

|

|

| Major depressive disorder | Bereavement exclusion eliminated; Chronic specifier eliminated |

| Persistent depressive disorder | New disorder (combines DSM-IV dysthymia and chronic major depression) |

| Premenstrual dysphoric disorder | New disorder |

| Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder | New disorder |

| Substance/medication induced depressive disorder | |

| Depressive disorder due to another medical condition | |

| Other specified depressive disorder | New disorder split from DSM-IV depressive disorder NOS |

| Unspecified depressive disorder | New disorder split from DSM-IV depressive disorder NOS |

| Bipolar and Related Disorders (BRDs) | New section split from DSM-IV mood disorders section New specifiers: anxious distress and severity; mixed features |

|

|

|

| Bipolar I Disorder | |

| Bipolar II Disorder | |

| Cyclothymic Disorder | |

| Substance/medication induced BRD | |

| BRD due to another medical condition | |

| Other specified BRD | New disorder split from DSM-IV bipolar disorder NOS |

| Unspecified BRD | New disorder split from DSM-IV bipolar disorder NOS |

| Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders (SSRDs) | Section renamed (section previously called somatoform disorders) |

|

|

|

| Somatic symptom disorder | New disorder (replaced DSM-IV somatoform disorder) New specifier: predominant pain (replaced DSM-IV pain disorder) |

| Illness Anxiety Disorder | New disorder, replaces DSM-IV hypochondriasis Insight specifiers eliminated New specifiers: care-seeking, care-avoidant |

| Conversion Disorder (Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder) | Renamed from DSM-IV conversion disorder |

| Factitious Disorders | No longer classified in the factious disorder section (section eliminated) No longer distinguishes between psychological versus physical symptoms New specifiers: single episode, recurrent episode |

| Psychological factors affecting other medical condition | New disorder |

| Other-specified SSRD | New disorder split from DSM-IV somatoform disorder NOS |

| Unspecified SSRD | New disorder split from DSM-IV somatoform disorder NOS |

Note. Empty cells in the “Changes from DSM-IV” column indicate that no major structural or specifier revisions were made. Criterion-level revisions are not included (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder). NOS = not otherwise specified; OCRD = obsessive-compulsive and related disorder; TSRD = trauma- and stressor-related disorder; BRD = bipolar and related disorder; SSRD = somatic symptom and related disorder.

One of the more noticeable structural changes among the DSM-5 EDs was the separation of obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and acute stress disorder (all classified as Anxiety Disorders in DSM-IV-TR) into two newly created diagnostic sections: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders and Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. These sections were added to reflect an appreciation for commonalities among disorders which were previously classified separately. For example, body dysmorphic disorder (previously a Somatoform Disorder), trichotillomania (previously an Impulse Control Disorder), and excoriation (skin picking) disorder (previously an Impulse Control Disorder) are now labeled as Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders to reflect their phenomenological overlap (e.g., repetitive/ritualistic behaviors often functioning to reduce distress) and shared treatment strategies (e.g., exposure and response prevention) with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Likewise, adjustment disorders (previously in a standalone Adjustment Disorder section) and reactive attachment disorder (previously a Disorder Usually First Diagnosed in Childhood) are now grouped with posttraumatic stress disorder as Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders in order to highlight the crucial etiological role of specific stressful events. A curious exclusion to this reorganization regards DSM-IV-TR hypochondriasis; although renamed illness anxiety disorder in DSM-5, this diagnosis remains grouped with the Somatic Symptom Disorders instead of the Anxiety Disorders.

Although a select number of EDs were eliminated from DSM-5 (e.g., undifferentiated somatoform disorder), this structural reorganization also resulted in the creation of several new disorders. For example, whereas problems with acquiring and discarding possessions were previously subsumed under the diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in DSM-IV, hoarding disorder is now officially recognized as an Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorder. Disinhibited social engagement disorder, previously a subtype of DSM-IV reactive attachment disorder, is now defined as a standalone Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorder in DSM-5. Although DSM-IV-TR dysthymic disorder and chronic major depression were consolidated as persistent depressive disorder, there are also two entirely new Depressive Disorders in DSM-5: premenstrual dysphoric disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Additionally, across all of the ED chapters (including the newly established sections), not otherwise specified diagnoses have been split into two separate conditions: “other specified” disorders (if the clinician chooses to assign a specifier) and “unspecified” disorders (if the clinician decides against assigning a specifier).

In addition to aforementioned structural changes and the addition/omission of disorders, DSM-5 EDs also underwent several lower-level changes, including alterations or reorganization of the criteria for specific disorders (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder) and the addition of new diagnostic specifiers. The introduction of the new ED specifiers allows diagnosticians to capture idiosyncratic diagnostic presentations in more nuanced ways. The new “with panic attacks” specifier, for example, can be applied to any DSM-5 diagnosis to indicate the presence of (cued) panic attacks that do not meet criteria for panic disorder. “With anxious distress,” a new specifier applied to mood disorders to characterize subclinical presentations of anxiety (e.g. difficulty concentrating due to worry when depressed), is a product of the substantial genetic (Kendler, 1996) and phenotypic (Brown, Campbell, et al. 2001) overlap that has been observed between generalized anxiety disorder and the mood disorders. Unfortunately, the clinical utility offered by these new specifiers comes at a cost to parsimony. We view the addition of numerous specifiers as yet another example of the splitting approach that has characterized DSM; it is likely to lead to meaningless distinctions among disorders that differ only superficially and which could better be conceptualized as trivial variations in underlying psychopathology.

In light of the limitations to these advancements, several serious problems persist in the DSM-5 classification system. DSM-5 has attempted to move toward improved reliability, as with splitting a number of DSM-IV diagnoses into distinct presentations in DSM-5. Nevertheless, preliminary research on the reliability of DSM-5 diagnoses has yielded mixed findings. Regier and colleagues (2013) conducted large-scale field trials of test-retest reliability for DSM-5 diagnoses, including several EDs. Test-retest reliability, measured by intraclass kappa, varied considerably across research sites. Furthermore, overall reliability for the EDs was not uniformly acceptable, with kappas ranging between 0.20 (generalized anxiety disorder) and 0.67 (posttraumatic stress disorder), and notably poor reliability for major depression (0.28). Although these coefficients may have been compromised by the use of unstructured clinical interviews, they are nonetheless concerning given that any improvement in reliability will ultimately be constrained by the limited construct validity of DSM-5 categorical diagnoses (e.g., unreliability due to threshold and differential diagnosis disagreements are likely to persist).

Indeed, DSM-5 also does little to address existing problems with the validity of diagnostic categories. Despite hypotheses that the DSM ED categories are more similar than different (Andrews, 1996; Barlow et al., 2013), the number of EDs increased in DSM-5. It seems inevitable that the high rates of ED comorbidity and other- or unspecified diagnoses (i.e., not otherwise specified) will continue. Regarding the dimensionality of the EDs, DSM-5 offers two forms of self-report dimensional assessment in Section III; cross-cutting (i.e., transdiagnostic) dimensional measures (pp. 733–741) and disorder-specific severity measures (available online only, www.psychiatry.org/dsm5). Despite early data indicating that these measures are reliable (Narrow et al., 2013), their validity and clinical utility (e.g., feasibility of widespread implementation) have yet to be systematically explored. Moreover, it is difficult to be optimistic that the Section III measures will serve as a catalyst for the integration of dimension-based ED diagnosis in future revisions of DSM: Unlike the alternative diagnostic model for the personality disorders in Section III, no systematic approach to diagnosis using the ED dimensional measures is delineated. Instead, DSM-5 states that the measures in Section III are “intended to help clinicians identify additional areas of inquiry…” and “may be used to track changes in the individual’s symptom presentation over time” (p.734). In our opinion, however, the measures are either overly broad (e.g., cross-cutting symptom measures diffusely assessing feelings of nervousness and panic) or too circumscribed (e.g., a separate disorder-specific measure for nearly every ED). Given the pervasiveness of DSM’s categorical approach to diagnosis and the infrastructure within which it exists (e.g., insurance claims corresponding to DSM diagnostic codes), we believe that any meaningful integration of dimensions in DSM must occur at the system level, rather than as an optional afterthought in Section III.

The collective changes in DSM-5 (or lack thereof) have been a topic of much debate. Some say the revised DSM represents strides forward in accurate and useful classification of mental disorders, while others believe the field has missed an opportunity to address problems in classification that have been perpetuated by our new manual. The National Institutes of Mental Health voiced opposition to the new DSM-5 in a statement by director Thomas Insel, who claimed that the “modest” revisions failed to provide a much-needed transition away from symptom-based classification (Insel, April 29, 2013). A focus on symptoms alone, said Insel, ignored critical information about biological, genetic, and cognitive features of mental disorders, as well as these disorders’ dimensionality. In other words, DSM-5 has over-emphasized reliability at the expense of validity. Accordingly, NIMH has distanced itself from DSM-5 in favor of the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative, which emphasizes that understanding of mental health should not be constrained by DSM categories but guided by emerging research in areas where our knowledge continues to grow (e.g., identifying biomarkers of mental disorders). This criticism was countered by David Kupfer (2013), chair of the DSM-5 task force, who pointed out the dearth of existing research on genetic and biological markers of mental disorders and suggested that the DSM-5 goes beyond symptom-based classification by organizing disorders based on shared characteristics and contextualizing diagnoses in cultural and developmental considerations.

Alternative Approaches for Emotional Disorder Classification

It is easy to appreciate both sides to this debate; DSM-5 does not substantively differ from DSM-IV-TR and biomarker-based classification is unarguably in its infancy. Nonetheless, it is difficult to ignore the numerous examples of how the DSM-5 task force failed to fully integrate or promote other radical but empirically based changes to ED classification. One clear example of DSM-5’s resistance to change regards the meta-structure of the EDs. Although DSM-5 recognizes the overlap of the EDs within and across the Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive, and Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders sections (e.g., discussing all of the EDs as “internalizing disorders,” p. 13), several other empirically based organizational distinctions were neglected. For example, in addition to identifying a higher-order “internalizing disorder” factor, studies have also repeatedly documented shared variance across ED diagnoses via lower-order factors representing “fear” (e.g., panic disorder, social anxiety) and “distress” (e.g., major depression, generalized anxiety) disorders (Krueger & Markon, 2006; Vollebergh et al., 2006; Watson, 2005). Very recent research even suggests that the fear and distress EDs are best modeled as continuous (not categorical) constructs, and that latent dimensions of these constructs outperform DSM disorder-specific variance in predicting important outcomes such as suicidality (Eaton et al., 2013). Although such findings could have been used to rationalize organizing the EDs by Fear and Distress Disorder sections, DSM-5 makes no mention of this distinction.

DSM-5 also overwhelmingly omits more progressive revisions involving the integration of empirically based dimensional ED assessment and diagnosis. For instance, Clark (2005) underscored the potential utility classifying the EDs using dimensions of neurotic temperament (NT; i.e., neuroticism, behavioral inhibition, negative affectivity) and positive temperament (PT; i.e., extraversion, behavioral activation, positive affectivity). In addition to being discussed in leading ED conceptual models (Barlow, 2002; Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998), numerous studies have documented the importance of NT and PT in predicting the severity, comorbidity, and course of the EDs (Brown, 2007; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998; Kasch, Rottenberg, Arnow, & Gotlib, 2002; Naragon-Gainey, Gallagher, & Brown, 2013; Rosellini, Fairholme, & Brown, 2011). Although high NT is associated with all of the EDs, it appears to be most strongly related to unipolar depression and generalized anxiety (Brown et al., 1998). In contrast, whereas low PT has been documented to predict depression, social anxiety, and possibly agoraphobia (Brown et al., 1998; Rosellini, Lawrence, Meyer, & Brown, 2011), high PT is associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder (Gruber, Johnson, Oveis, & Keltner, 2008). Research also suggests that NT may fully account for the shared variance across DSM ED categories (i.e., comorbidity). In an adolescent sample, for example, Griffith and colleagues (2010) found that NT displayed a near tautological relationship (r = .98) with a higher-order internalizing disorder factor modeled using lifetime ED diagnoses. Although DSM-5 alludes to the importance of NT and PT in its brief discussion of “Risk and Prognostic Factors” for each ED, it does not delineate a systematic approach to ED diagnosis that includes personality/temperament constructs.

One could argue for an extreme nosological revision in which the EDs are classified solely on the basis of continuous assessments of NT and PT. Such an approach could potentially improve diagnostic reliability and validity by acknowledging the dimensional and overlapping nature of EDs (e.g., reducing threshold disagreements via a dimensional approach, reducing differential diagnosis disagreements/comorbidity by focusing on only two dimensions). Although empirically robust, assessment and diagnosis based on NT and PT alone would be far too nonspecific for practical use by clinicians. For example, although one could safely presume that a patient with high NT and low PT is experiencing clinically significant depression and/or social anxiety concerns, the additional assessment of lower-order phenotypes is needed in order to obtain a clear picture of a patient’s presenting problems (e.g., relative severity of depression, social evaluation concerns, possible experiences of panic attacks, etc.). In other words, a dimensional approach to ED classification would also need to include the assessment of other constructs necessary for appropriate treatment planning (e.g., creating a hierarchy of treatment targets). In order to minimize unnecessary “splitting,” however, selection of additional dimensions would need to be based on empirically supported transdiagnostic (i.e., cross-cutting) phenotypes. For example, a transdiagnostic assessment of panic attacks/autonomic arousal could be helpful because cued attacks and related distress may occur within the context of several disorders (see panic attack specifier on p. 214, DSM-5).

Even with inclusion of such transdiagnostic dimensions, one cannot ignore the practical advantages of using diagnostic categories. In addition to being easier to communicate (opposed to discussing an exhaustive list of dimensional scores, see First, 2005), categorical representations of the EDs will continue to be required by managed care organizations when making decisions about treatment reimbursement for the foreseeable future. Given the empirical limitations of a purely categorical approach and practical limitations of a purely dimensional approach, researchers have thus recently focused on hybrid classification schemes that utilize both dimensional and categorical components (Maser et al., 2009). Indeed, there have been several preliminary evaluations of mixed dimensional-categorical approaches to classifying the personality disorders (Eaton, Krueger, South, Simms, & Clark, 2011), eating disorders (Eddy et al., 2010), and childhood behavioral disorders (e.g., attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder; Drabick, 2009; Martel, Goth-Owens, Martinez-Torteya, & Nigg, 2010). These studies use statistical techniques such as latent class/profile analysis and factor mixture modeling to identify empirically derived profiles whose validity is subsequently examined relative to DSM categories. For example, Eddy et al. (2010) used latent class analysis to identify three eating disorder profile types using dimensional ratings from a clinical interview. Subsequent analyses demonstrated the profile types to be associated with corresponding DSM eating disorder diagnoses (e.g., most individuals with bulimia nervosa were included in the same profile type, i.e., convergent validity), and that the profile types were more differentiated than DSM eating disorders on a number of clinical outcomes (e.g., % ideal body weight, self-esteem, i.e., incremental validity).

A Profile Approach to Emotional Disorder Classification

In 2009, we (Brown & Barlow, 2009) proposed a hybrid approach to ED classification in which dimensional scores are plotted into profiles and assigned categorical labels based on empirically derived cut points (i.e., clinically/statistically significant thresholds for the array of dimensional indicators). In addition to including NT (i.e., anxiety/neuroticism/ behavioral inhibition) and PT (i.e., behavioral activation/positive affect) for etiological and prognostic reasons (e.g., strong relationship of NT with depression and generalized anxiety; ability of NT and PT to predict the longitudinal course of ED phenotypes), our profile approach also involved the assessment of several empirically indicated transdiagnostic ED phenotype dimensions. These dimensions were selected in the face of evidence showing that NT and PT alone would not provide adequate information about the foci of ED symptoms (i.e., for treatment planning, see Brown & Barlow, 2009 for discussion). The dimensions were empirically derived from literature documenting their relevance across multiple EDs and their clinical utility in assessment and treatment planning (e.g., differential diagnoses, identifying targets for intervention, risk management). The dimensions of interest include the following:

Depressed Mood (DM) - DM reflects excessive sadness and anhedonia. Consideration of recent (i.e., past two weeks) mood would be important because of the high rates of ED/mood disorder comorbidity (Brown, Campbell et al., 2001) and its necessity in appropriate risk planning (e.g., associations of DM severity with suicide outcomes; Uebelacker, Strong, Weinstock, & Miller, 2010).

Autonomic arousal (AA) – AA represents a dimensional assessment of panic and is defined by the experience of physiological symptoms of sympathetic nervous system activation. As previously mentioned, the assessment of AA would be useful because panic attacks and their symptoms “can occur in the context of any mental disorder” (p. 215, DSM-5). Importantly, however, elevated AA appears to be most strongly related to panic disorder, agoraphobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Brown et al., 1998; Brown & McNiff, 2009).

Somatic anxiety (SOM) – SOM reflects anxiety focused on one’s experience of somatic symptoms (i.e., including but not limited to AA). In addition to being a defining feature of somatic symptom and illness anxiety disorder, assessing SOM would be helpful based on evidence from psychopathology studies documenting health-related concerns across several other EDs (e.g., panic disorder, Clark, 1986; obsessive-compulsive disorder, Abramowitz et al., 1999; generalized anxiety, Lee et al., 2011). DSM-5 also acknowledges the transdiagnostic nature of SOM in regards to differentiating anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders (e.g., p. 314, 317, 321).

Social evaluation concerns (SEC) – SEC represents anxiety focused on performance situations and social interactions. Knowledge of SEC would be useful because high SEC is prototypical of social anxiety disorder but is also seen across the spectrum of anxiety disorders, particularly generalized anxiety (Rapee, Sanderson, & Barlow, 1988) and posttraumatic stress disorder (Adkins et al., 2008). DSM-5 also underscores the role of embarrassment fears across several EDs (p. 206–207).

Intrusive cognitions (IC) – IC reflects the experience of intrusive and nonsensical thoughts, images, and impulses. Although this is the defining feature of several obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, research also suggests that knowledge of IC is important because this phenotype is also related to generalized anxiety disorder (intrusive worry images, Tallis, 1999). Likewise, DSM-5 discusses the experience of intrusive thoughts in several differential diagnosis sections, particularly for the trauma spectrum disorders (e.g., p., 202, 225, 241).

Traumatic re-experiencing and dissociation (TRM) – TRM can be thought of as the experience of negative affect focused on past traumatic events, but also includes dissociative and flashback experiences. In addition to being the defining feature of acute stress and posttraumatic stress disorders, knowledge of TRM is also important given its transdiagnostic overlap with the dissociative disorders (see DSM-5 p. 291, 296, 301 for an extensive discussion of the overlap of these disorders)

Avoidance (AVD) – AVD of external and internal cues (i.e., triggers) of negative affect is crucial in assessing the EDs. DSM-5 directly discusses the role of avoidance by including it as a criterion for several ED diagnoses (e.g., agoraphobia, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder). Avoidance of internal cues has also been extensively recognized by clinicians as a transdiagnostic feature of the EDs, particularly since identification of avoidance of somatic or interoceptive cues associated with panic attacks and other strong negative emotions (interoceptive avoidance; Barlow, 1988). Also, Hayes, Wilson, Strosahl, Gifford, and Follette (1996) underscored experiential avoidance as the primary factor in the etiology and maintenance of EDs via their rationale for acceptance and commitment therapy.

Importantly, this list of phenotypes is not exhaustive; several additional cross-cutting vulnerabilities and phenotypes are also likely relevant for the broad spectrum of EDs (e.g., the phenotypic overlap of body image concerns with the eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorder). Nonetheless, the seven empirically-derived dimensions described above can serve as a starting point in the development of a profile approach to classification based on transdiagnostic ED vulnerabilities and phenotypes. We believe that inclusion of these constructs in a profile approach to ED classification could address several of the aforementioned limitations in diagnostic reliability and validity. For example, the use of dimensional indicators would reduce diagnostic unreliability due to threshold disagreements because decisions would not have to be made regarding a disorder causing clinically significant interference or distress; information pertaining to indicator severity could always be included in an individual’s profile. Utilization of dimensional indicators would also increase diagnostic validity by recognizing taxometric findings that support the dimensional (rather than categorical) nature of ED phenotypes. The focus on cross-cutting transdiagnostic constructs would also increase diagnostic reliability and validity by reducing differential diagnosis decisions and lowering comorbidity rates. For instance, rather than deciding between a diagnosis of panic disorder, illness anxiety disorder, or both, a patient reporting recent out of the blue panic attacks, lifelong worry about heart disease that triggers panic attacks, and reassurance seeking behaviors (e.g., going to the ER when having cued and uncued attacks) could be characterized by a single profile type with elevated levels of NT, AA, and SOM.

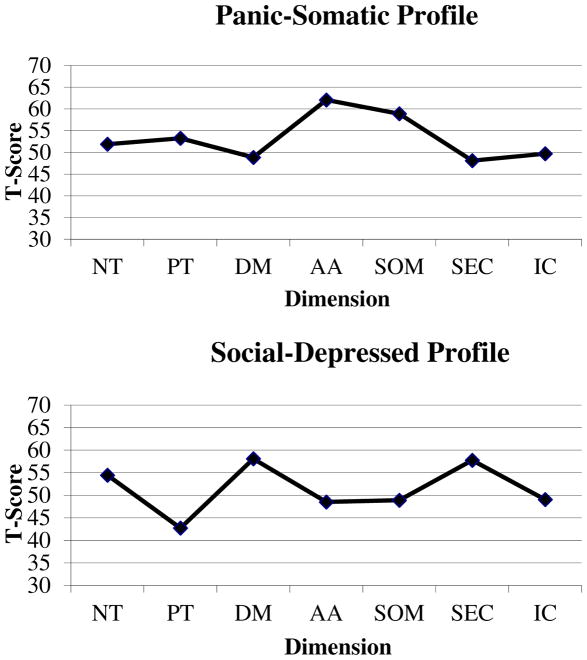

We recently evaluated the validity of such a profile approach to ED classification (Rosellini, 2013). To our knowledge, this is the first empirical examination of a profile approach to ED classification. In a sample of 1,218 outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders, we used latent class analysis to identify groups of individuals sharing similar ED profiles based on a subset of Brown and Barlow’s (2009) transdiagnostic dimensional indicators: NT, PT, DEP, AA, SOM, SEC, and IC. A six-class (i.e., profile) solution provided the best model fit and was the most conceptually interpretable (see Figure 1 for two examples of these plotted profiles). The classes were labeled (1) Negligible-Mild (non-pathological scores across all indicators), (2) Panic-Somatic (slight elevation on NT, larger elevations on AA and SOM), (3) Social-Depressed (elevations on NT, DM and SEC, low levels of PT), (4) Mildly-Neurotic (average NT and below average scores on the remaining indicators), (5) Severe-Comorbid (pathological levels across all indicators), and (6) Obsessed-Worried (slight elevation on NT and DM, larger elevation on IC). The convergent validity of these classes with DSM-IV categories was supported using both cross-tabulations (e.g., 76% of the Social-Depressed class carried a social phobia diagnosis) and multinomial logistic regression models (e.g., diagnoses of social phobia and major depression were associated with significantly higher odds of being in placed in the Social-Depressed class). More importantly, the incremental validity of the profiles was also supported; hierarchical regressions were used to show that the profiles consistently accounted for unique variance in other ED outcomes above and beyond categorical DSM-IV diagnoses (e.g., the Panic-Somatic class significantly predicted clinician-rated and self-reported agoraphobic avoidance while controlling for diagnoses of panic disorder and agoraphobia).

Figure 1.

Two example latent profiles adapted from “Initial Development and Validation of a Dimensional Classification System for the Emotional Disorders,” by A. J. Rosellini, 2013. Indicator means within each profile type were converted to T-Scores for presentational clarity (i.e., indicators scaled in different metrics). NT = neurotic temperament; PT = positive temperament; DM = depressed mood; AA = autonomic arousal; SOM = somatic anxiety; SEC = social evaluation concerns; IC = intrusive cognitions.

We believe these findings provide exciting initial support for the utility of ED profiles as an adjunct to DSM diagnoses. In addition to a profile label such as Panic-Somatic being easy to communicate, knowledge of a patient’s transdiagnostic indicator scores would provide information pertaining to overall and specific phenotype severities that could be particularly useful for clinicians in treatment planning (e.g., developing a hierarchy of treatment targets). For example, regardless of DSM diagnoses, a patient who has larger elevations on AA and SOM than all other phenotype dimensions might benefit from prioritization of interoceptive exposure exercises. Moreover, information pertaining to NT and PT could potentially give clinicians a sense of who is at greatest risk of developing (i.e., etiology) and maintaining (i.e., prognosis) ED psychopathology. In the absence of diagnostic information, the profiles could also possibly be used to approximate DSM disorder (e.g., most outpatients in the Social-Depressed class had a diagnosis of Social Phobia). However, a great deal of additional work is needed to validate a profile approach to ED classification. For example, latent class analysis needs to be applied to a broader range of ED dimensions (e.g., including indicators of trauma, mania, and avoidance) and in different samples (e.g., epidemiological samples). In addition, the clinical utility of profile approaches to ED classification remains untested – it is unclear if clinicians would accept, understand, or use an ED profile in practice. Nonetheless, we also foresee how profile approaches to classification could be expanded to other classes of disorders (e.g., externalizing disorder profiles characterized by dimensions of disinhibited temperament, anger, substance use, etc).

The Multidimensional Emotional Disorder Inventory

One noteworthy limitation of this preliminary evaluation of a profile approach to ED classification was our reliance on several questionnaires to assess the ED vulnerabilities and phenotypes of interest. If a profile (or any dimensional) approach to ED classification is to be seriously considered, one must be cognizant of the burden that could fall on patients, clinicians, and researchers. Rather than having to determine if a patient’s symptoms exceed a few categorical thresholds (i.e., the assessment of entire criteria sets is not always necessary), a profile approach would require clinicians to obtain a full assessment of the breadth of ED dimensions of interest (i.e., all dimensions must be assessed in detail in order to plot severity levels and identify a profile type). Although substantial efforts have been made to develop and validate empirically based assessments of the ED vulnerabilities and their phenotypes, existing measures typically provide a circumscribed approach by focusing on only a limited number of dimensions. For example, whereas the Behavioral Inhibition/Activation Scales (Carver & White, 1994) can be used to assess NT and PT but not DM, AA, SOM, IC, or SEC, the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (Rapee et al., 1994/1995) assesses features related to SOM and SEC but not NT, PT, or IC. Thus, in order to assess all ED dimensions of interest, a significant amount of time would be needed to select, administer, and score a disparate array of measures.

With these issues in mind, our team has recently developed the Multidimensional Emotional Disorder Inventory (MEDI), a self-report questionnaire intended to assess transdiagnostic vulnerabilities and phenotypes for our profile approach to ED classification. The MEDI is unique in that it is intended to provide a brief (i.e., using as few items as possible) but rich assessment of NT, PT, DM, AA, SOM, SOC, TRM, and AVD using a response scale that ranges from 0 (not characteristic of me/does not apply to me) to 8 (extremely characteristics of me/applies to me very much). As prior efforts have extensively validated self-report instruments for these constructs or close derivatives, MEDI items were developed based on item content that had previous empirical support. Specifically, psychometric studies of well-validated questionnaires were reviewed to identify the “best functioning” descriptors for each dimension (e.g., items with factor loadings > .70), and MEDI items were subsequently generated using similar types of descriptors. Items were worded to be consistent with a Likert response scale ranging from 0 (not at all characteristic of me/does not apply to me) to 8 (extremely characteristic of me/applies to me very much). One important advantage of the MEDI is that its scales are intended to be transdiagnostic in nature; that is, items were worded to emphasize features of each the phenotypes that cut-across multiple DSM disorder categories. For example, IC items focused on the intrusive nature of thoughts and images (e.g., “I have thoughts or images that I find unacceptable”) rather than overly specific thought or image content (e.g., related to stressors, contamination, sex, violence, etc.). After a large initial item pool was developed using this approach, two co-authors of the present review (T.A.B and D.H.B) and a third ED expert voted on which items to include in a 55-item pilot version of the MEDI that was administered to ED outpatients.

Although the MEDI is currently still under development, a pilot study produced promising results by finding initial support for its multidimensional latent structure and the convergent and discriminant validity of its subscales compared to other well-validated self-report questionnaires (Rosellini, 2013). In addition to the hypothesized eight-factor solution providing good fit using an exploratory structural equation modeling framework (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), each of the eight subscales demonstrated acceptable reliability (α range = 0.77 to 0.93). Based on findings from this initial study, a handful of MEDI items have been revised or replaced and data are currently being collected as part of an NIMH-supported project on the classification and psychopathology of EDs. Once validated and distributed, future research will ultimately be needed to evaluate the MEDI as a classification instrument (i.e., using mixture modeling) and its ability to track change in the EDs over time and with treatment (i.e., as a transdiagnostic treatment outcome measure).

As the MEDI was not yet developed, Brown and Barlow (2009) provided a hypothetical profile based on a former patient at the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders (CARD). Accordingly, in order to illustrate the advantages and utility of a profile approach classification using the MEDI, we next provide two real case examples based on patients that have recently presented for an assessment and treatment at CARD. In addition to briefly summarizing their presenting problems, we focus on comparing and contrasting both patient’s DSM-5 diagnoses (assigned using the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-5, Brown & Barlow, 2014) with their MEDI profiles.

Case A

This patient is a female in her late 20s who presented to CARD seeking treatment for “anxiety about everything,” leading to distraction, fidgeting, impulsivity, and trouble sitting still. Although she also reported “always” struggling with depression, she identified worry and anxiety as her main reasons for seeking treatment. Current symptoms included excessive, difficult to control worry about her health (e.g., becoming paralyzed, contracting HIV), the health of others, the well-being of her family, and interpersonal relationships, accompanied by muscle tension, restlessness and difficulty concentrating. Co-occurring with the worries was a history of chronic depression, beginning in childhood, intermixed with hypomanic episodes. She reported current depression characterized by low mood, anhedonia, weight loss, fatigue, psychomotor retardation, guilt and indecision. She also expressed ongoing (i.e., since childhood) unwanted thoughts of contamination, horrific and sexual imagery, and several repetitive behaviors involving internal repetition, counting, checking social media, skin picking, and hair pulling (the latter two causing noticeable scabbing and baldness). Lastly, she reported anxiety in social situations involving performance (e.g. acting or giving a speech) and interaction (e.g., attending parties, being assertive) and that she often avoided these situations.

On the basis of this clinical presentation, five DSM-5 EDs were assigned: bipolar II disorder (currently depressed, with severe anxious distress), trichotillomania, excoriation disorder, social anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although she met all the key and associated features for generalized anxiety disorder, the anxious distress specifier was assigned rather than a standalone diagnosis because these symptoms occurred exclusively within the course of her assigned mood disorder (i.e., the DSM hierarchy exclusion). She also reported significant worries about her health; however, illness anxiety disorder could not be assigned because these worries occurred within the context of her anxious distress/contamination fears and did not involve excessive health-related behaviors. Additionally, despite being in a life-threatening car accident and having some current trauma-related symptoms (e.g., occasional intrusive memories, cued panic attacks when driving, and avoidance of situations related to the trauma), posttraumatic stress disorder could not be assigned because her symptoms of negative alterations in cognition or mood (i.e., DSM-5 Criterion D) and hyperarousal (i.e., DSM-5 Criterion E) were not sufficient in number and severity to warrant a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder, nor did she experience clinically significant distress or impairment.

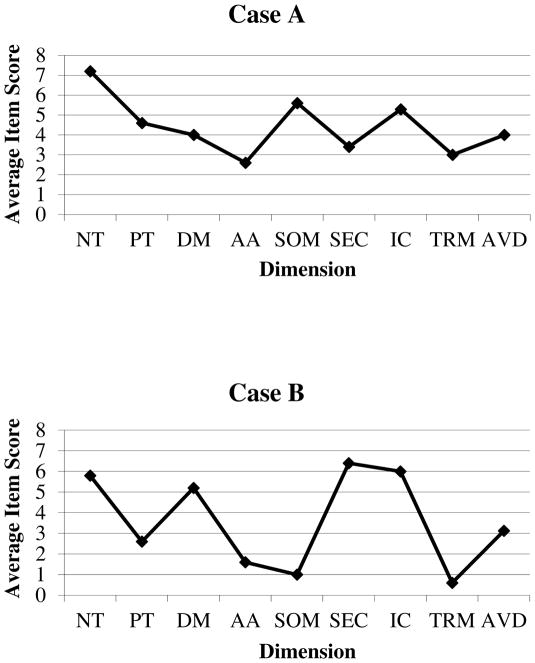

As seen in Figure 2, the MEDI profile for Case A is consistent with her DSM-5 diagnoses. The profile shows, for example, average item scores between 3 and 5 on the DM and SEC dimensions, likely a reflection of her moderately severe depression and social anxiety disorder (i.e., elevated DM and SEC are somewhat characteristic of this patient). The patient also endorsed elevated PT as being somewhat characteristic of her, which is consistent with her predisposition to experience hypomanic episodes (cf. Case B). Moreover, the larger elevation on the IC dimension (which was endorsed as being very characteristic of this patient) may be a parsimonious representation of the patient’s three comorbid Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. The MEDI profile also offers information that is obfuscated and/or lost via DSM-5 diagnoses. For example, Case A’s largest profile elevation is seen for NT; in addition to suggesting a strong predisposition to developing EDs (as evidenced by her extensive comorbidity), the heightened NT likely also reflects this patient’s significant interference/distress over generalized anxiety symptoms that, despite being the primary reason for seeking treatment, DSM-5 forces one to capture using the anxious distress specifier. Moreover, whereas DSM forces us to subsume her associated health-related worries under the anxious distress specifier (because she does not meet diagnostic threshold for a somatic symptom or related disorder), this predominate area of worry is captured via her second largest elevation on the SOM dimension. Finally, the profile also captures her subthreshold levels of TRM and AA that were omitted by DSM-5 but may nonetheless be clinically relevant.

Figure 2.

Plotted MEDI profiles from the two case examples. Average item scores within each dimension were used for presentational clarity (i.e., total scores were not used because not all dimensions were assessed using the same number of items). The MEDI uses a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not characteristic of me/does not apply to me) to 8 (extremely characteristics of me/applies to me very much). Using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5, Case #1 was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder (with current depression, moderate; with anxious distress, severe), trichotillomania, excoriation disorder, social anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Case #2 was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder and persistent depressive disorder (early onset; with moderately severe pure dysthymic syndrome and melancholic features). NT = neurotic temperament; PT = positive temperament; DM = depressed mood; AA = autonomic arousal; SOM = somatic anxiety; SEC = social evaluation concerns; IC = intrusive cognitions; TRM = traumatic re-experiencing and dissociation; AVD = avoidance.

Case B

This patient is a male in his early 20’s who presented to CARD seeking treatment for social anxiety, general worries, and occasional periods of low mood. He reported anxiety in and avoidance of a number of social situations, including parties, dating, talking on the phone, being assertive and starting and maintaining conversations. He also described feeling depressed more days than not over the past ten years, accompanied by symptoms of pessimism, low self-esteem, indecision, self-blame, anhedonia, weight loss, and intermittent suicidal ideation. Within the past four years, the patient reported extremely uncontrollable worry about several areas in his life, particularly worry about work, the health of significant others, and interpersonal issues. His worry led to procrastination and trouble making decisions, and it was accompanied by restlessness and occasional irritability, poor concentration and sleep disturbance. Finally, he reported a history of obsessive thoughts (doubting whether he had done homework, unwanted blasphemous thoughts) and compulsive behaviors (e.g., counting, mental repetition of prayers) that, although present, were not currently causing significant interference or distress.

Only two disorders were assigned for this patient: social anxiety disorder and persistent depressive disorder (early onset; with moderately severe pure dysthymic syndrome). Although this patient also met all the key and associated features of generalized anxiety disorder, similar to Case A, this diagnosis could not be assigned because these symptoms occurred only within the course his unipolar mood disorder. In contrast to Case A, however, the anxious distress specifier was not assigned because only one of these symptoms (difficulty concentrating due to worry) was present the majority of days of the persistent depressive disorder (at least two symptoms must be present for the majority of days in order to assign the specifier).

Also seen in Figure 2, the MEDI profile for this patient is again consistent with his DSM-5 diagnoses. Three of the four largest elevations (i.e., all very characteristic of this patient) are observed on the SEC (i.e., reflecting the social anxiety disorder), NT (i.e., reflecting a predisposition to ED comorbidity, particularly generalized worry and depression), and DM (i.e., reflecting the moderately severe current depression). In addition, Case B’s predisposition to and experience of comorbid unipolar depression and social anxiety disorder are reflected by comparatively low (i.e., slightly characteristic) levels of PT, and also contrasts Case A’s predisposition to a bipolar II disorder that is reflected by a higher score on PT. Furthermore, the MEDI profile for this patient also offers incremental data over DSM-5 diagnoses alone, particularly the lack of a DSM-5 diagnosis or specifier to capture his generalized anxiety disorder symptoms. In addition to these symptoms being captured by the heightened level of NT, the second largest elevation seen on the IC dimension is likely a reflection of patient’s high levels of uncontrollable worry and/or subthreshold thoughts of blasphemy and doubting (i.e., this patient reported NT and IC to be very characteristic of themselves).

Treatment Implications of the Profile Approach

In parallel to the development of a hybrid dimensional-categorical approach to emotional disorders over the past decade we have been focusing on developing a psychological treatment that addresses the more fundamental higher order processes of anxiety and mood disorders (Barlow, Allen & Choate, 2004; Barlow et al., 2011). This treatment, known as the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP) contains two fundamental changes in directions from existing evidence-based psychological treatments for anxiety and mood disorders. First, recognizing that many of the principle components of diagnostic-specific individual treatments for various emotional disorder contains similar operations (e.g. greater awareness of emotional experience and responding, reduction of both experiential and in vivo avoidance behavior, exposure to both internal and external emotion provoking cues) the UP introduces parsimony to the treatment of the full range of emotional disorders by focusing on five core modules broadly adaptable to individual cases. Each of these modules can be used to target several (e.g., physical sensations module targeting AA, SOM, and TRM), if not all (e.g. emotional awareness and acceptance module) of the transdiagnostic phenotypes discussed here (and probably covarying with changes in NT). Second, recognizing broad patterns of comorbidity and the presence of sub-threshold symptoms that often accompany these individual disorders, as clearly reflected in Case A and Case B described above, our basic conception of the targets of treatment in the UP have moved from symptomatic expression of individual disorder constructs such as panic disorder or social phobia, to more fundamental processes that are more closely related to the expression of temperament itself, particularly NT. For example, notice in Case A and Case B that NT is elevated in both cases while levels of the individual profiles reflecting transdiagnostic processes, such as intrusive thoughts of social evaluative concerns, vary from individual to individual. Notice also in the cases described above that DSM-5, despite some improvements over previous editions, does not make explicit symptom patterns that do not cross the threshold of severity thereby qualifying for a diagnosis despite the potential relevance to treatment of the symptoms in each case. Even more important is that other diagnoses, such as generalized anxiety disorder, that may most closely reflect the clinical expression of NT (along with depression) are precluded altogether since, for both Case A and Case B, the symptoms occurred exclusively within the course of the assigned mood disorder.

Elsewhere, we review evidence that, contrary to some assumptions temperament can be malleable and potentially impacted by treatment both psychological and pharmacological (Barlow et al., in press). Thus, we now conceptualize the fundamental goal of the UP as directly addressing the strong reactions of distress to intense negative emotions themselves, distress that leads to a variety of cognitive and behavioral distortions such as faulty attributions and appraisals and avoidant coping behavior across the emotional disorders (Campbell-Sills, Ellard & Barlow, 2014; Ellard et al., 2010). Indeed, it is the modulation of marked distress and response to emotional provocation triggered by either internal or external cues in our view that affects the intensity and frequency of emotional experiences going forward thereby impacting temperamental constructs.

Initial evaluations of the UP looking at outcomes for individual disorder constructs (e.g. panic disorder, social anxiety disorder) in a series of preliminary trials have produced positive results. Direct effects on temperament are also evident (Carl, Fairholme, Gallagher, Thompson-Hollands, & Barlow, 2013). Currently we are in the midst of a large five-year clinical trial comparing the UP with well-established evidence-based psychological treatments for individual specific anxiety disorders based on the patient’s principal diagnosis. This trial is conceptualized as an equivalence trial in that the relative efficacy of the more parsimonious UP with its five core modules compared to individual protocols for each of the anxiety disorders would provide an advantage for the UP based on cost effectiveness and ease of dissemination. However, as noted above, more fundamental goals include a closer examination of the direct effects of this protocol on temperament which we conceptualize as the principal target.

Pending the outcome of these and other trials evaluating this new approach, the parallel development of a more dimensional approach to emotional disorders as represented in this paper and in the creation of the MEDI would provide a more efficient and effective way to assess the full range of emotional disorders including common patterns of comorbidity and sub threshold symptom presentations thereby providing an ideal process and outcomes assessment instrument for transdiagnostic treatment approaches such as the UP. New developments in research programs in the coming years will determine whether this promise can in fact be realized.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support. Portions of this article were supported by Grant MH039096 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: Brown). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Portions of this article were presented by A. J. Rosellini as posters at the 47th annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, November 2013.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. None to report.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Brigidi BD, Foa EB. Health concerns in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1999;13:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins JW, Weathers FW, McDevitt-Murphy M, Daniels JB. Psychometric properties of seven self-report measures of posttraumatic stress disorder in college students with mixed civilian trauma exposure. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:1393–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. Comorbidity in neurotic disorders: The similarities are more important than the differences. In: Rapee RM, editor. Current Controversies In The Anxiety Disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;16:397–438. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Sauer-Zavala S, Carl JR, Bullis JR, Ellard KK. The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism: Back to the future. Clinical Psychological Science in press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (ADIS-5) New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, McNiff J. Specificity of autonomic arousal to DSM-IV panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Diagnostic comorbidity in panic disorder: Effect on treatment outcome and course of comorbid diagnoses following treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:408–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM–IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Ellard KK, Barlow DH. Emotion regulation in anxiety disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carl JR, Fairholme CP, Gallagher MW, Thompson-Hollands J, Barlow DH. The effects of anxiety and depressive symptoms on daily positive emotion regulation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment in press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:461–470. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised. Albany, NY: Phobia and Anxiety Disorders Clinic; 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Moras K, Barlow DH, Rapee RM, Brown TA. Reliability of DSM-III-R anxiety disorder categories using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised (ADIS-R) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DA. Can a developmental psychopathology perspective facilitate a paradigm shift toward a mixed categorical–dimensional classification system? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Wall M, … Grant BF. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:86. doi: 10.1037/a0029598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, South SC, Simms LJ, Clark LA. Contrasting prototypes and dimensions in the classification of personality pathology: Evidence that dimensions, but not prototypes, are robust. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1151–1163. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy KT, Le Grange D, Crosby RD, Hoste RR, Doyle AC, Smyth A, Herzog DB. Diagnostic classification of eating disorders in children and adolescents: How does DSM-IV-TR compare to empirically derived categories? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione T, Barlow DH. Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB. Clinical utility: A prerequisite for the adoption of a dimensional approach in DSM. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:560–564. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, Sutton JM. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1125–1136. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Johnson SL, Oveis C, Keltner D. Risk for mania and positive emotional responding: Too much of a good thing? Emotion. 2008;8:23–33. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Pope HG. Affective spectrum disorder: Does antidepressant response identify a family of disorders with a common pathophysiology? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:552–564. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.5.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Transforming diagnosis. Director’s Blog. 2013 Apr 29; Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml.

- Janca AA, Burke JR, Isaac MM, Burke KC. The World Health Organization Somatoform Disorders Schedule: A preliminary report on design and reliability. European Psychiatry. 1995;10:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0924-9338(96)80340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper F, Hiller W, Rist F, Bailer J, Witthöft M. Somatic symptom reporting has a dimensional latent structure: Results from taxometric analyses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:725. doi: 10.1037/a0028407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Major depression and generalised anxiety disorder same genes,(Partly) different environments—Revisited. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;168:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollman DM, Brown TA, Liverant GI, Hofmann SG. A taxometric investigation of the latent structure of social anxiety disorder in outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:190–199. doi: 10.1002/da.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DL. Chair of the DSM-5 task force discusses future of mental health research [News Release] 2013 May 3; Retrieved from http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Press%20Releases/2013%20Releases/13-33-Statement-from-DSM-Chair-David-Kupfer--MD.pdf.

- Lee S, Ma Y, Tsang A. A community study of generalized anxiety disorder with vs. without health anxiety in Hong Kong. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Goth-Owens T, Martinez-Torteya C, Nigg JT. A person-centered personality approach to heterogeneity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:186–196. doi: 10.1037/a0017511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser JD, Norman SB, Zisook S, Everall IP, Stein MB, Schettler PJ, Judd LL. Psychiatric nosology is ready for a paradigm shift in DSM-V. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K, Gallagher MW, Brown TA. Stable “trait” variance of temperament as a predictor of the temporal course of depression and social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:611–623. doi: 10.1037/a0032997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narrow WE, Clarke DE, Kuramoto SJ, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ, Greiner L, Regier DA. DSM-5 Field Trials in the United States and Canada, part III: Development and reliability testing of a cross-cutting symptom assessment for DSM-5. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:71–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12071000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus HA, McQueen LE, Elinson L. Subthreshold mental disorders: Nosological and research recommendations. In: Phillips KA, First MB, Pincus HA, editors. Advancing DSM: Dilemmas in Psychiatric Diagnosis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2003. pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Sanderson WC, Barlow DH. Social phobia features across the DSM–III–R anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1988;10:287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Clarke DE, Kraemer HC, Kuramoto SJ, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. DSM-5 Field Trials in the United States and Canada, part II: Test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:59–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini AJ. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Boston University; Boston, MA: 2013. Initial Development and Validation of a Dimensional Classification System for the Emotional Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini AJ, Fairholme CP, Brown TA. The temporal course of anxiety sensitivity in outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders: Relationships with behavioral inhibition and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini AJ, Lawrence AE, Meyer JF, Brown TA. The effects of extraverted temperament on agoraphobia in panic disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:420–426. doi: 10.1037/a0018614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Ruscio J, Keane TM. The latent structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: A taxometric investigation of reactions to extreme stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:290–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Ruscio J. The latent structure of analogue depression: Should the Beck Depression Inventory be used to classify groups? Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:135–145. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Borkovec TD, Ruscio J. A taxometric investigation of the latent structure of worry. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:414–422. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipherd JC, Salters-Pedneault K. Attention, memory, intrusive thoughts, and acceptance in PTSD: An update on the empirical literature for clinicians. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2008;15:349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Patient Edition/Non-patient Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tallis F. Unintended thoughts and images. In: Dalgleish T, Power MJ, editors. Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Strong D, Weinstock LM, Miller IW. Likelihood of suicidality at varying levels of depression severity: A re-analysis of NESARC data. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40:620–627. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: the NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:597. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: a quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Samuel DB. Diagnostic categories or dimensions? A question for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-fifth edition. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:494–504. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, … Wittchen HU. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]