Abstract

Vancouver, Canada is experiencing an overdose crisis due to the proliferation of fentanyl and related analogues and novel overdose response interventions are being implemented across multiple high overdose risk environments, including emergency shelters. We draw on ethnographic fieldwork and qualitative interviews to examine how social, structural, and physical contexts at two emergency shelters implementing a peer-based supervised injection intervention influenced injection drug use and overdose risks. Findings reveal that the implementation of this intervention reduced stigma and shame through the normalization of drug use in shelter spaces, and yet underlying social norms and material constraints led people to inject alone in non-designated injecting spaces. Whereas these spatial dynamics of injection drug use potentially increased overdose vulnerability, an emerging sense of collective responsibility in relation to the overdose crisis led to the routinization of peer witnessing practices across the shelter environment to extend the impact of the intervention.

INTRODUCTION

The day-to-day experiences of people who use drugs (PWUD) are shaped by multiple social, structural, and physical environments. In turn, these environments shape how drugs are used, as well as drug-related risks and harms (Ramos et al., 2009; Rhodes, 2009). There is a growing body of literature that has examined how these contexts influence drug use and related outcomes at both the macro and micro levels (Cooper & Tempalski, 2014; Tempalski & McQuie, 2009). Research has illuminated how environmental contexts of neighbourhoods (e.g., building conditions, zoning restrictions, availability of services, perceptions) impact PWUD. Spatial isolation in built environments (e.g., presence of light posts on streets, lengths of roads) has shown how these can frame health and safety risks (Deering et al., 2014). Other types of spatial isolations, such as area restrictions prohibiting PWUD from going into certain neighbourhoods, have been shown to increase vulnerabilities to violence and unsafe drug use due to a lack of access to health services in these neighbourhoods (McNeil, Cooper, Small, & Kerr, 2015; Shannon et al., 2009). Conversely, neighbourhoods with high availability of rehabilitation programs have shown to be associated with lower likelihood of injection drug use (Linton, Jennings, Latkin, Kirk, & Mehta, 2014). Perceptions about neighbourhoods also impact drug use. For example, neighbourhoods perceived as risky environments affect the spatial negotiations of youth who use drugs and the everyday experiences of violence and other harms (Fast, Shoveller, Shannon, & Kerr, 2010). Lastly, dilapidated buildings and low-income housing (e.g., single room occupancy hotels), has been associated with HIV and overdose risks (Davidson et al., 2003; Hembree et al., 2005; Maas et al., 2007).

Literature on drug use in urban spaces has suggested that overdose response interventions should focus more on housing-based responses (Bardwell, Collins, McNeil, & Boyd, 2017; Siegler, Tuazon, Bradley O’Brien, & Paone, 2014). However, for homeless PWUD, their day-to-day lives are comprised of constant spatial negotiations of “activity spaces” (e.g., places where drugs are acquired, drug use spaces, social services) where overdose vulnerability and resilience may vary depending on the location (Martinez, Lorvick, & Kral, 2014). Homeless PWUD experience multiple health inequities that are exacerbated by their housing vulnerability (Aldridge et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2009). Within the context of homelessness, the concept of structural vulnerability is helpful in understanding these inequities. Here, structural vulnerability refers to how positions within social hierarchies render particular groups (e.g., Indigenous, homeless) susceptible to risk and suffering as a result of the intersection of structural and social-historical forces. Such macro-level forces (e.g., racism, stigma) produce and reinforce the social-structural marginalization of these groups and lead to a variety of negative health and social outcomes (e.g., health, economic, housing) (Quesada, Hart, & Bourgois, 2011; Rhodes et al., 2012). Structural vulnerability thus extends prior conceptualizations by more fully accounting for the role of socio-cultural processes in producing the structural violence that constrains individual agency and increases their susceptibility to harm among and across particular groups (Bourgois, Holmes, Sue, & Quesada, 2017). Further, modifications to social, structural, and environmental contexts (e.g., policy changes, intervention implementation) can further increase or decrease the structural vulnerability of particular groups, including PWUD, by impacting their access to social and material resources, among other variables (McNeil, Kerr, et al., 2015), which have the potential to lead to varying degrees of agency (Farmer, 2004). Importantly, structural vulnerability can also frame how people interact with space, and the spatial dimensions of drug use in particular. For homeless PWUD, in particular, their lack of housing inevitably leads to drug use in public spaces. Studies on public injecting have found that public environments (e.g., parks, alleyways) increase risks whereby PWUD make attempts to rush or hide their drug use due to associated stigma and shame attached to this practice in public (Rhodes et al., 2007), as well as address safety relating to harassment, assault, or policing (Ahmed, Long, Huong, & Stewart, 2015; Cooper, Moore, Gruskin, & Krieger, 2005; Small, Rhodes, Wood, & Kerr, 2007).

For homeless PWUD accessing emergency shelters with minimal access to harm reduction services creates risks for residents who use drugs by limiting their ability to use life-saving interventions (e.g., naloxone) (Wallace, Barber, & Pauly, 2018). For those encountering barriers to accessing emergency shelter (e.g., abstinence-only policies), structural vulnerabilities are exacerbated by constant negotiations of other high-risk environments such as unregulated “shooting galleries” (i.e., private indoor spaces where PWUD congregate to use drugs) (Parkin & Coomber, 2009; Philbin et al., 2008) and public spaces (DeBeck et al., 2009; Scheim, Rachlis, Bardwell, Mitra, & Kerr, 2017), which increase other drug-related risks such as syringe sharing and HIV infection (Bozinoff et al., 2017; Hien, Giang, Binh, & Wolffers, 2000; Hossain, 2000; Tobin, Davey-Rothwell, & Latkin, 2010).

In public spaces, homeless PWUD are subjected to routine surveillance (e.g., police, social stigma). We examine the experiences of surveillance of homeless PWUD within multiple drug use spaces, primarily within emergency shelters. We do this by drawing upon Foucault’s work on regulation (Foucault, 1977), where he illustrates how surveillance in disciplinary societies acts as a mechanism of control that effectively regulates citizens while maximizing the efficiency of social institutions (e.g., prisons). Foucault argues that surveillance is omnipresent and also internalized (Foucault, 1977). Previous studies drawing upon concepts of regulation and surveillance to understand injecting practices and public health interventions have highlighted practices by institutions that govern drug use risk behaviours including SIS (Bourgois, 2000; Fischer, Turnbull, Poland, & Haydon, 2004; Keane, 2009; Miller, 2005; Szott, 2014). For example, while playing an integral role in reducing a variety of harms associated with injection drug use (e.g., overdose, HIV infection), supervised injection sites (SIS) have the potential to act as environments that promote the exclusion of “disorderly” PWUD from public spaces when mobilized to promote ‘public order’, as well as through operational models fostering surveillance and social control (Fischer et al., 2004). While these ‘safer environment interventions’ (SEI) are implemented to mitigate the impacts of social, structural, and physical environments on risk and harm by intervening to reshape the environmental contexts of drug use (McNeil & Small, 2014; Rhodes et al., 2006) and have been largely developed through grassroots campaigns led by drug user organizations (Kerr et al., 2006; McNeil, Small, Lampkin, Shannon, & Kerr, 2014), this research has shown that they can nonetheless reproduce certain forms of social control. We include Foucault’s theoretical understanding of internalized surveillance and control along with the various environmental contexts that affect the ways in which homeless PWUD navigate and negotiate spaces for drug use in Vancouver, Canada.

For homeless PWUD in many settings, health inequities are exacerbated by overlapping housing and opioid crises, and in particular in Vancouver, Canada. In 2017, over 3600 people were experiencing homelessness in Vancouver, representing a 30% increase from 2014 (BC Non-Profit Housing Association & M. Thomson Consulting, 2017). Lack of access to housing is perpetuated by social-structural forces, including gentrification (Burnett, 2014), insufficient social assistance (Klein, Ivanova, & Leyland, 2017), and shortcomings of housing policies (Lee, 2016). Vancouver is also experiencing an overlapping overdose crisis due to the proliferation of fentanyl-adulterated drugs. In 2017, the Province of BC reached over 1400 overdose-related deaths (British Columbia Coroners Service, 2018). While there has been an increase in overdose response interventions in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) – a neighbourhood significantly affected by poverty, drug dependency, and homelessness – there have been few SEIs to address overdose in other neighbourhoods. Similar to community-based responses to drug use through the establishment of peer-led SIS internationally (Hedrich, 2004; Tweed & Rodgers, 2016; van Beek, 2003; Wolf, Linssen, & de Graaf, 2003), RainCity Housing, a supportive and emergency housing organization, implemented “peer witness injection programs” in two emergency shelters – located in neighbourhoods that are between three to four kilometers away from the DTES – in which people can use drugs under supervision by peer staff who play a supportive role and are able to respond in case of an overdose (e.g., administer naloxone, contact emergency medical services). Both shelters have designated injection rooms equipped with tables, chairs, and harm reduction equipment. While these services are mainly used by shelter residents (approximately forty at each), other PWUD in the neighbourhoods also use these services.

The aims of this article, are to examine the impacts of social, structural, and physical environments on spatial negotiation for homeless PWUD in emergency shelters in Vancouver. Specifically, we investigate the day-to-day experiences of surveillance and structural vulnerability on homeless PWUD and the ways in which physical, social, and structural contexts shape negotiations of the spaces PWUD access for drug use, including those within these shelter environments.

METHODS

This study involved rapid ethnographic data collection, which occurred over a two-week period starting at the end of March and ending in April 2017. Qualitative methods were employed, including semi-structured interviews and ethnographic observation at two low-barrier shelters. Semi-structured interviews sought to capture individual experiences of homelessness, drug use, and using the peer witness injection room. Ethnographic observation investigated the physical structures and layouts of each building, drug use practices within the shelter, and interactions between residents, peer workers, and other staff. Ethical approval was obtained through the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

For the individual interviews, we purposively sampled 24 residents at the shelters (twelve at each). Eligibility criteria required to participate in the interviews included being a shelter resident and using drugs on-site. The lead author kept a record of demographic information to ensure that the study included a diversity of participants in terms of gender and Indigenous ancestry (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). Participants were recruited by word-of-mouth and potential participants were referred to our research team by shelter staff. Participants provided informed consent to participate and each received $30 cash honoraria, as per best practices in our research setting (Collins et al., 2017). Participants chose their own pseudonyms. A guide was used to facilitate the interviews regarding experiences with overdose, drug use, and using drugs in various spaces at the shelters. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy by the lead author.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Sample characteristics (n=24) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Average (mean) | 41 |

| Range | 26-59 |

| Gender | |

| Women | 6 |

| Men | 18 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 13 |

| Racialized/Indigenous | 11 |

| Emergency shelter sites | |

| site #1 | 12 |

| site #2 | 12 |

In addition, the lead author completed approximately 30 hours of overt ethnographic observation in the shelters during the study period to gain first-hand knowledge of the social, structural, and physical environments that impacted spatial negotiation and drug use in the shelters that may not be captured in a traditional interview. This approach was also utilized to further enhance the trustworthiness of interview data (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Entrance to shelters for fieldwork purposes was approved by shelter management. During ethnographic observation, the lead author took field-notes and photographs, which were later used to further contextualize the research (Schwartz, 1989).

We employed a team approach in developing the coding framework for the data. Members of our research team each reviewed a portion of the transcripts, field notes, and photographs individually and then met as a group and developed a coding framework using a priori themes as well as thematic categories that emerged from the dataset (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). We used NVivo 11 (a qualitative data software) to manage and code the data into themes and subthemes for analysis. The theoretical analysis is informed by concepts of surveillance and environmental impacts, which were used to explicate the themes and subthemes from our dataset beyond thematic description.

RESULTS

Participants’ accounts emphasized how homelessness impacted what spaces they used drugs in, which, in turn, shaped their injecting practices. Given the structural context of Vancouver’s ongoing housing crisis, people living in poverty and at risk of homelessness are in and out of emergency shelters while others set up their encampments by appropriating public or publicly-accessible urban spaces (e.g., tents in parks or alleyways). Their subsequent negotiation of public spaces within the context of their wider structural vulnerability shaped their everyday experiences, including street violence and harassment as well as the production of unsafe and unsanitary conditions for living in and using drugs in public spaces. Herein, we examine the multiple ways in which various social, structural, and physical environments impact the ways in which participants negotiated emergency shelter spaces for their drug use.

From policed to normalized spaces

Consistent with previous research (Cooper et al., 2005; Rhodes et al., 2007; Small et al., 2007), participants described multiple experiences of structural vulnerability in public through mechanisms of policing, discrimination, surveillance, and shame, which shaped their constant negotiation of spaces for drug use. Due to the limited housing options, people experiencing homelessness often access emergency shelters that tend to be high-barrier and run abstinence-only programs, though some lower threshold shelter options have emerged. In contrast to using drugs in public, participants in this study discussed the shelters where they stayed and used drugs as differing greatly depending on their harm reduction policies and programs (or lack thereof). At the two RainCity emergency shelter sites, which were considered low-barrier and included harm reduction policies and programs such as the peer witness injection program, the social-structural environment fostered by these harm reduction approaches disrupted the forms of structural vulnerability typically experienced elsewhere. For example:

It’s a big difference, man. You don’t have to worry about anything, you don’t have to fuckin’ worry if anybody’s gonna pull up [i.e., police]. You know what I mean? You’re not in public, you’re not in the eyes of the public, man…and you’re in your own space. (Adidas, white man, site #2)

This quote illustrates the ease of drug use within this environment, in contrast to the need to rush use when using in public spaces that are heavily surveilled by police, leading to displacement and hidden use (Small, Kerr, Charette, Schechter, & Spittal, 2006). Participants generally expressed a sense of relief due to relaxed rules pertaining to drug use, as described by one participant: “Here it’s a little more casual because it’s almost like you’re allowed to do it” (Simon, white man, site #1). Here, the structural-environmental context reshaped a broader set of socio-spatial relations that produce injecting-related norms elsewhere (e.g., surveillance and hidden use in public washrooms) to reduce drug-related risks and increased a sense of agency among some participants.

Aside from comparing their experiences between using drugs in public versus using drugs at the shelter, some participants also drew comparisons to their experiences staying at other more high-barrier shelters. Participants most commonly spoke about the rules and regulations of other shelters:

There’s just too much structure at these other shelters. There’s no drug use, you have to be in by 8 o’clock…and this place is pretty come and go as you please. (James, Indigenous man, site #1)

Participants had very different experiences between RainCity shelters and other shelters in the city, seeing RainCity shelters as having less barriers and rules versus other shelters where, like public spaces, participants felt that they had to hide their use or were at risk the negative consequences of policing/surveillance. Participants specifically described the ways in which these prohibitive rules at other shelters impacted people’s risk of overdose, because in shelters where people are hiding their use due to restrictions around drug use on site, they are at a greater risk of dying. As previous research has demonstrated (Wallace et al., 2018), these perceptions and experiences show how social and structural environments of high-barrier shelters can have a negative impact on people’s drug use and associated overdose risks.

The use of drugs at the RainCity shelters were often described in ways that normalized drug use. By having designated spaces for drug use specifically, participants felt more at ease than in other spaces (e.g., abstinence-only shelters). When asked about his first time using the witness injection room at the shelter, one participant said:

The first time it was good. There was no judgement and everybody was open about it…and asking if we needed help…and they check on us regularly on a basis to make sure we’re okay, so that’s alright. It makes you feel safe, right? If you get really, really high you know you’re safe a bit (Smoke, Indigenous man, site #1).

This highlights the routinization of the staff in checking-in on participants, all while approaching participants it in a way in which they felt safe and in a judgement-free environment. Other participants described their experiences using drugs in the designated shelter spaces as comforting. For example:

It’s easier to relax, to do your drugs. And it’s just you feel safe and comfortable. I definitely don’t mind coming here to do drugs…They have everything that you need all the time and just the staff is right on top of everything, you know? And they try to help everybody out the best that they can, and they’re just very helpful. (Biggy, white man, site #2)

Participants felt comfortable in the space not just because the shelter had a peer witness injection site, but also because of the on-going support from staff and peer witnesses. It is understandable that experiences like these may feel odd at first, given how they contrast to using drugs in public spaces and other high-barrier emergency shelters.

Group dynamics affected choice of spaces for drug use

Aside from the structural aspects of the RainCity shelters (e.g., harm reduction policies), the social environment impacted the ways in which participants navigated spaces in the shelter. The social dynamics amongst PWUD, peer workers, and staff played a significant role in shaping drug use within the context of an overdose crisis. Some participants felt an added sense of group responsibility when using drugs at the shelter versus other spaces. For example, according to Kegan:

It’s kind of like going to a club versus a pub…Like you kind of want to use the dope slower, so that way like you could be more social and not look like a fool I guess, versus going all out. (Kegan, Indigenous man, site #1)

According to study participants, using drugs with, or in front of other PWUD, was not just interpreted as having a social function (e.g., “hanging out”, conversing), but using with others also functioned as a responsibility by being around others in case of an overdose. When asked why he used the injection room, Alex explained: “Because that’s where everybody goes, so I just socialize with them. And you feel safer in case you do drop and there’s people around instead of being alone” (Alex, Indigenous man, site #1). The injection room, while being a space that has a social function, was also a space that was understood by participants as a safer use zone, which contrasts to the structural vulnerability experienced through other socio-spatial relations (e.g., public shame and appropriating hidden spaces for drug use).

Concerns regarding overdose within the shelter were discussed by all participants and thus collective responsibility in regards to supervising drug use and preparedness in responding to overdoses was present across shelter spaces – designated or otherwise – where drug use took place. For example: “Everybody’s concerned. We all look out for each other for the most part…I care, you know. I don’t want to see people dying from drug use” (Will, white man, site #2). This concern and responsibility for others’ drug use across various spaces in the shelter was discussed by some participants in ways that suggest there was a communal bond between PWUD in the shelter where, for example, “it’s more kind of family-oriented, where other people will assist in [responding to] overdoses” (Biggy, white man, site #2). Another participant described the social responsibility of the shelter residents as a community that cares, as seen in the following excerpt:

These guys, like I told you, you talk about community, man. They care about each other. They may yell at each other. ‘You owe me money for this drug,’ or whatever, blah-blah-blah. If one of them drops with an overdose, man, bam, on top, hurry, trying to get the person alive. That’s wild…And that’s what I call love. You know, think about it. 30 minutes ago, that guy was calling that guy this and that. He has an overdose, now that guy and that guy, the one guy’s helping the other guy not to die, man. That’s love…That’s community. That’s sociably correct. (Misfit, white man, site #2)

This excerpt highlights the perspective that while there may be interpersonal issues among the residents at the shelters, some participants still felt a sense of group responsibility to respond to someone who is overdosing there. These social dynamics connect directly to the drug practices and group responsibility toward other shelter residents.

There were also multiple pressures that shaped the social-environmental context of the shelter and, in turn, contested how space was used. One’s social interactions with others were dependant on what spaces they would use to inject drugs (e.g., in designated injection rooms or single-user washrooms). Some participants, for example, discussed how other residents would ask them for drugs, which would impact their decisions to use some spaces over others, with varying levels of overdose risk. The following excerpt illustrates these social pressures and how they impact the spaces in which people use:

Well, it’s just like as soon as I pick up [drugs], I run back to here. And depending on what kind of mood I’m in, if I have quite a bit of stuff, I’ll sit down and I’ll share it with people and stuff. But I’ve been finding lately that people take my kindness as a weakness and wait until I nod out and steal my money and my drugs. So now I tend to go into the bathroom stall [to use] (Simon, white man, site #1).

In physical environments that are overwhelmingly inhabited by PWUD, the availability of, and access to, drugs from other residents does impact how people negotiate the spaces where they will use their drugs. For example, Willy almost always used drugs alone. When asked if he tells others that he is going to be using, he said: “No, not really because you get people grinding you for your dope” (Willy, Indigenous man, site #2). Experiences of exploitation or having people constantly ask for drugs, impact how and where participants used their drugs in the shelter. This is, in part, a material constraint in the context of managing drug use in relation to prohibition and poverty that drive up the cost of drugs and shape social relations and, in turn, influence spatial navigation.

Using drugs alone in the shelter was a common theme among study participants. While participants generally found drug use at the shelters to be more supportive and comforting, there were still elements of structural vulnerability (e.g., surveillance) similar to those experienced by participants when they were injecting drugs in public. Despite efforts to accommodate drug use in the shelters, perceptions of surveillance transferred into the shelter space. Here, the shelters function both as sites of abeyance (where PWUD hide their drug use or where this use is contained) and sites of sustenance and care (where PWUD are supported), highlighting the complexity of the constant day-to-day spatial negotiations of PWUD (DeVerteuil, 2014). Some discussed embarrassment or shame when using in front of even their peers. For example, “I use drugs by myself because I am embarrassed about it. Like it’s been 16 years since I’ve had like a straight fucking month of sobriety and like it’s just hard” (Kegan, Indigenous man, site #1). Due to past negative experiences, other participants preferred the privacy of using alone, as demonstrated in the following excerpt: “In [the shelter] staff could just walk by and check on us. It’s fine, right? But me, I have a problem sometimes with privacy and stuff, and I don’t like being seen” (Fox, South Asian man, site #1). Using drugs alone in private spaces was also a habitual practice for some participants, showing the ways in which social and structural vulnerability permeate other physical spaces. According to Alison, “I’m a little uncomfortable about using in front of anybody, right? Because I was so used to just using alone. Like when I’d do my down, I had to go into the bathroom, even at home” (Alison, white woman, site #2). While participants had their different reasons for using alone, ultimately the choices of drug use spaces were influenced by the social dynamics and environments within the shelters, which led to varying degrees of agency among participants.

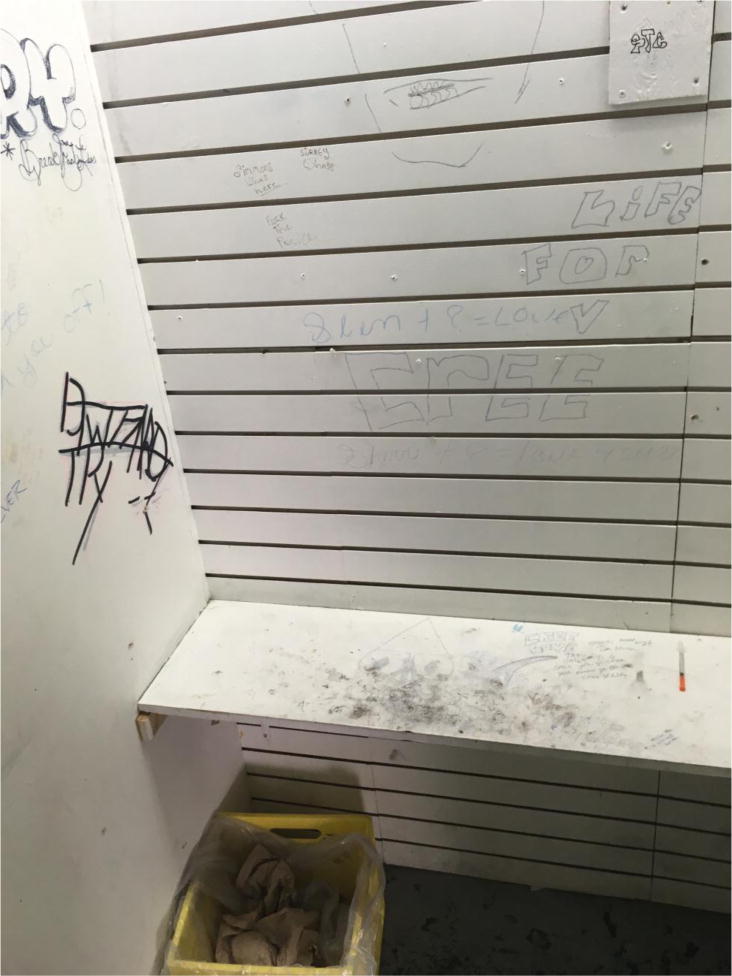

Negotiating space constraints across the shelters

Given the structural-physical environmental context stemming from austerity, shelter management and staff were required to adapt to the physical limitations of the buildings and construct makeshift spaces for the purposes of drug use. Space was limited in various ways at each of the sites. From ethnographic observation, the injection room at site #2 (see Figure 3) had limited capacity and could barely accommodate two people. This space constraint impacted peoples’ ability to use them. The following quotation illustrates this issue:

They don’t want people in the open, shooting up. That’s why in the back they have a little curtain, you know, a space. But it only fits like two or three people, right? So, when you’ve got 42 people here, and I’d say a majority of the people are using IV [intravenously], so I think there should be built a bigger space (Chris, white man, site #1).

Figure 3.

Injection room at site #2

The need for larger or more spaces was seen as a necessity to accommodate everyone who used drugs at the shelter.

From ethnographic observation at both sites, PWUD most frequently used the injection rooms, washrooms or showers, and their personal beds as spaces for using drugs, highlighting the choice to use multiple drug use spaces at the shelter; one exercised without the threat of punitive measures from shelter staff or management. Common areas such as the kitchens or the living rooms were mostly avoided. For washrooms and showers, participants discussed how these were frequently used and the overdose risk that comes with using in those spaces (see Figure 1). For example, Smoke discussed how, because it is so common for people to use in these spaces, he checks the washrooms to see if anyone has overdosed: “I do regular checks now because of people overdosing in the bathrooms so many times and they don’t get checked on and they could be overdosing” (Smoke, Indigenous man, site #1). A participant at the other site, said that washrooms are checked more frequently due to the risk of overdosing alone. Alison, a white woman, said, “Here they’re on top of it quickly to the point where they’re annoying people, like knock, knock, knock, on the doors of the bathroom. And people get mad and say ‘fuck off’ to the staff and I’m like, ‘don’t talk to them like that…they want to make sure you’re alive.” While participants were able to identify the risks with using the washrooms and showers alone, they were still frequently used – likely due to some of the social dynamics and limitations of physical space as illustrated above. Given the participants’ need for spaces that feel comfortable, it is not surprising that people also chose to use drugs in their beds. For example, Keri said people prefer to use at their beds due to ease of access as well as space limitations elsewhere in the shelter: “There is one tiny injection room that one chair fits in. So, people use the bathrooms, but there are only four bathrooms, so a majority of people use at their own beds…it’s easier to just use at your bed” (Keri, Indigenous woman, site #2). This illustrates the ways in which physical limitations impact how people negotiate their drug use within the shelter space.

Figure 1.

A shower room at site #1

The size and number of spaces was not the only component that influenced the drug use practices of participants in the shelters. Similar to studies on public environments that constrain efforts to use drugs in a hygienic way (Small et al., 2007), participants also discussed the sanitary conditions of various spaces as impacting their drug use. Some were concerned about people leaving out their used injection equipment. For example:

Well there’s rigs everywhere. Like even though there’s lots of little safety bins, people are just useless. People, because they might not get a good smash or whatever…they just throw it in the garbage or on the table, anywhere. It’s so casual. (Simon, white man, site #1)

The issues of discarded injection equipment and unsanitary conditions were very notable during all ethnographic site visits, as evident in the photos (see Figures 1–3). While these issues were frequently present at the shelters, some participants blamed non-residents for issues of cleanliness of the space, which impacted where they chose to use their drugs. For example:

Like I’d rather sit on my bed than sit in the bathroom, you know. It’s cleaner. I think these bathrooms are filthy all the time. Like they’re always filthy, man. It’s gross. Like the people come off the streets and they don’t fucking clean up after themselves. It’s nasty. Yeah. and even if you go look right now you could probably find some open rigs sitting in the bathroom, guaranteed. (Jeff, Indigenous man, site #2)

Some participants felt that the volume of people accessing the peer witness injection services – many of which were not residents of the shelters – impacted the sanitary conditions of the injection spaces. Regardless of who or what was to blame for these conditions – outsiders, staff, peer workers, residents, few resources, or the volume of people – the structural and physical environment of various spaces in the shelters played a prominent role in influencing PWUD’s drug use patterns. These limited choices either increased participants’ risk of overdose vulnerability by using alone or appropriating other non-designated drug use spaces (e.g., their beds) or increased other health risks through injecting drugs in unsanitary conditions of the designated drug use spaces.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we found that the homeless PWUD in our study negotiated emergency shelter spaces for drug use in many ways. Spatial negotiations were shaped by social, structural, and physical forces on a daily basis for homeless PWUD, including stigma, police surveillance, rules, group dynamics, and sanitary conditions. Within the shelter context, in contrast to high-barrier or abstinence-only shelters, the peer witness injection program provided designated spaces to accommodate drug use as well as peer workers to provide support, education, and overdose response. This intervention was utilized by all participants to varying degrees, where some used drugs in the designated spaces while others used in more private spaces (e.g., bathrooms). Despite the implementation of this SEI, agency and spatial negotiations by PWUD within the shelters were impacted similarly to drug use in other surveilled spaces.

Conceptualizing spaces for drug use through an investigation of the social, structural, and physical environmental contexts provides a robust understanding of the ways in which multiple forces impact spatial negotiation for homeless PWUD. Consistent with previous research on public injection (Cooper et al., 2005; Rhodes et al., 2006), our research highlights how experiences of stigma, shame, and surveillance create risk environments for PWUD. These everyday experiences of drug use become normalized, and within the context of the overdose and housing crises, the structural vulnerabilities of homeless PWUD in particular are intensified given their lack of access to private spaces. Spatial negotiations of homeless PWUD are complex, where, as seen with our study participants, homeless PWUD are tasked with choosing between hiding their drug use which increases their risk of overdose death or using more publicly, which increases other associated risks (e.g., harassment, arrests). While past research has demonstrated multiple risk environments for PWUD in Vancouver’s DTES (Burnett, 2014; Ciccarone & Bourgois, 2016; McNeil, Shannon, Shaver, Kerr, & Small, 2014; Shannon, Ishida, Lai, & Tyndall, 2006; Small et al., 2006) – a neighbourhood with a notable history of novel harm reduction interventions such as SIS (Kerr, Oleson, Tyndall, Montaner, & Wood, 2005; Kerr et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2004) – there is a lack of research on harm reduction interventions and drug use focusing specifically on homeless PWUD in other neighbourhoods where PWUD and related services are less concentrated.

Previous research has emphasized the need for SEIs to address harms associated with drug use (McNeil & Small, 2014; Rhodes et al., 2006). Although there is a growing body of literature on the importance for these types of interventions, and while a recent study calls for more comprehensive harm reduction interventions in emergency shelters (Wallace et al., 2018), a study of targeted interventions in emergency shelters and their impacts on PWUD is an area that has not been explored. This article, thus, provides a valuable addition to the literature not only in providing an example of interventions in emergency shelters located outside of the DTES, but also in highlighting the ways in which agency and spatial negotiations within shelters are also complicated by social, structural, physical contexts, structural vulnerabilities, and habitual drug practices of homeless PWUD. Importantly, our participants described how past negative daily experiences with using drugs in front of others in public spaces shaped their daily practices and thus complicated their negotiation of designated drug use spaces within the shelter.

Foucault’s (1977) work on surveillance, as a disciplinary mechanism of social control that permeates all aspects of institutional and everyday life, offers a means to understand why some PWUD continue to use drugs in non-designated spaces that confer an increased risk of overdose even when they are provided with designated spaces through a peer witness injection program. The heightened disciplinary practice of surveillance and control experienced by homeless PWUD in their everyday lives became both normalized and internalized by participants. As seen in past research (Ahmed et al., 2015; Small et al., 2007), PWUD constantly experience stigma and live in fear of punitive measures when using drugs in the context of criminalization. Our participants described similar experiences when navigating public spaces and other high-barrier shelter spaces. Further, similar to research on surveillance and social control of PWUD through public health interventions (Boyd, Cunningham, Anderson, & Kerr, 2016; Fischer et al., 2004; Szott, 2014), our study demonstrates that even the most well-intentioned harm reduction interventions can have their limitations, particularly given the structural vulnerabilities of homeless PWUD in the context of other overarching social, structural, and physical environments that foster social control and internalized surveillance. This begs the question of how to provide supportive spaces for drug use while also effectively addressing overdose risk given the internalization of drug-using norms and expectations. While problematized by some, many of our study participants described multiple benefits to using the peer witness injection spaces, which were often supported by harm reduction policies, supportive peer staff, and intergroup social dynamics. However, given the larger contexts in which PWUD live, drug use spaces in shelters are similar to spaces of containment, which impose boundaries and spatial separation (Tempalski & McQuie, 2009). While PWUD may have positive experiences within the shelter, these are not reflective when PWUD leave and use other spaces that increase their risk (Parkin & Coomber, 2009). This is particularly true given the lack of harm reduction interventions (e.g., SIS) in the neighbourhoods of the shelters in this study. Therefore, to better address the macro-level contexts and the structural vulnerabilities of homeless PWUD, there is a need for targeted peer-led SEIs across multiple environments. As we have demonstrated elsewhere, peer-led overdose response interventions are effective not just in responding to overdoses in a shelter setting, but also in terms of nominal power dynamics and trust based on shared lived experience compared to non-peer staff (Author 1 et al., 2018). These could include interventions such as mobile outreach SIS to target PWUD in other neighbourhoods that lack SEIs and overdose prevention sites integrated in other spaces (e.g., drop-in centres) with a mixture of shared spaces and private individual booths to mitigate experiences of surveillance and shame. Further, the promotion of these services and other harm reduction policies in other high-barrier shelters is needed to increase the accommodation of drug use, decrease punitive measures for drug use. Normalizing drug use across multiple environments could lessen the stigma and shame experienced by PWUD and the supportive nature of these environments may be internalized in place of surveillance. In addition, further research and consultation with homeless PWUD is paramount to ensure the programs and spaces for drug use address the multiple contexts and structural vulnerabilities of PWUD, including distinct socio-spatial contexts that are created through the implementation of harm reduction interventions (Strike, Guta, de Prinse, Switzer, & Chan Carusone, 2014).

There are some limitations to our study. First, while we made an effort to reach a diversity of emergency shelter residents, their experiences may not be reflective of all others residing in the shelters and those with differing perspectives may have chosen not to participate in this study. Second, this study focuses on two winter emergency shelters in Vancouver and therefore the outcomes of this research may not be applicable to other low-barrier emergency shelters. Third, while study participants did discuss their drug use in other spaces, the interview guide was focused primarily on drug use in shelters and the peer witness program and thus may not have captured all of the participants’ experiences using drugs in other settings. Further research on the contextual forces that impact drug use for homeless PWUD in other settings should thus be a top priority.

In conclusion, this study documents the ways in which homeless PWUD negotiate spaces for drug use. Our findings illustrate the impacts of physical, social, and structural contexts on spatial negotiations for PWUD and how these contextual factors are internalized and problematize the effectiveness of SEIs such as peer witness injection programs. Considering these challenges when developing SEIs within emergency shelters and other spaces will help to optimize service delivery for homeless PWUD, and thereby reduce risks associated with drug use.

Figure 2.

Injection room at site #1

Highlights.

The overdose crisis requires novel and targeted public health interventions

Social, structural, and physical contexts can create barriers and opportunities

Harm reduction and peer-led interventions can normalize drug use in shelters

Experiences of surveillance are internalized by homeless people who use drugs

These experiences impact drug use in normalized spaces

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank RainCity Housing and the study participants for their contributions to this research. This study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA044181). Geoff Bardwell is supported by a Mitacs Elevate Postdoctoral Fellowship from Mitacs Canada. Thomas Kerr is supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Foundation Grant (20R74326). Ryan McNeil is supported by awards from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and CIHR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed T, Long TN, Huong PT, Stewart DE. Drug injecting and HIV risk among injecting drug users in Hai Phong, Vietnam: a qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, Nordentoft M, Luchenski SA, Hartwell G, Hayward AC. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bardwell G, Collins AB, McNeil R, Boyd J. Housing and overdose: an opportunity for the scale-up of overdose prevention interventions? Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0203-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BC Non-Profit Housing Association & M Thomson Consulting. 2017 Homeless Count in Metro Vancouver. 2017 Retrieved from Burnaby, BC: http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/homelessness/HomelessnessPublications/2017MetroVancouverHomelessCount.pdf.

- Bourgois P. Disciplining addictions: the bio-politics of methadone and heroin in the United States. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2000;24(2):165–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1005574918294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Holmes SM, Sue K, Quesada J. Structural Vulnerability: Operationalizing the Concept to Address Health Disparities in Clinical Care. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):299–307. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Cunningham D, Anderson S, Kerr T. Supportive housing and surveillance. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2016;34:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozinoff N, Wood E, Dong H, Richardson L, Kerr T, DeBeck K. Syringe Sharing Among a Prospective Cohort of Street-Involved Youth: Implications for Needle Distribution Programs. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(9):2717–2725. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1762-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Coroners Service. Illicit drug overdose deaths in BC, January 1 2007 - December 31, 2017. 2018 Retrieved from British Columbia: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/public-safety-and-emergency-services/death-investigation/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf.

- Burnett K. Commodifying poverty: gentrification and consumption in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Urban Geography. 2014;35(2):157–176. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2013.867669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, Bourgois P. Injecting Drugs in Tight Spaces: HIV, Cocaine and Collinearity in the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver, BC. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;33:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AB, Strike C, Guta A, Baltzer Turje R, McDougall P, Parashar S, McNeil R. We’re giving you something so we get something in return”: Perspectives on research participation and compensation among people living with HIV who use drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;39:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF, Tempalski B. Integrating place into research on drug use, drug users’ health, and drug policy. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles, California: Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Into Practice. 2000;39(3):124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PJ, McLean RL, Kral AH, Gleghorn AA, Edlin BR, Moss AR. Fatal heroin-related overdose in San Francisco, 1997-2000: a case for targeted intervention. J Urban Health. 2003;80(2):261–273. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Small W, Wood E, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Public injecting among a cohort of injecting drug users in Vancouver, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(1):81–86. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Rusch M, Amram O, Chettiar J, Nguyen P, Feng CX, Shannon K. Piloting a ‘spatial isolation’ index: the built environment and sexual and drug use risks to sex workers. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil G. Does the Punitive Need the Supportive? A Sympathetic Critique of Current Grammars of Urban Injustice. Antipode. 2014;46(4):874–893. doi: 10.1111/anti.12001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. An Anthropology of Structural Violence. Current Anthropology. 2004;45(3):305–325. doi: 10.1086/382250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fast D, Shoveller J, Shannon K, Kerr T. Safety and danger in downtown Vancouver: understandings of place among young people entrenched in an urban drug scene. Health Place. 2010;16(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Turnbull S, Poland B, Haydon E. Drug use, risk and urban order: examining supervised injection sites (SISs) as governmentality. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2004;15(5):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2004.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. In: Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. Sheridan A, translator. New York: Pantheon Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D. European report on drug consumption rooms. 2004 Retrieved from Lisbon. [Google Scholar]

- Hembree C, Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Markham Piper T, Miller J, Tardiff KJ. The urban built environment and overdose mortality in New York City neighborhoods. Health & Place. 2005;11(2):147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien NT, Giang LT, Binh PN, Wolffers I. The social context of HIV risk behaviour by drug injectors in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. AIDS Care. 2000;12(4):483–495. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. Injecting drug users, HIV risk behaviour and shooting galleries in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19(4):413–417. doi: 10.1080/713659428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane H. Foucault on methadone: beyond biopower. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(5):450–452. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Oleson M, Tyndall MW, Montaner J, Wood E. A description of a peer-run supervised injection site for injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):267–275. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Peeace W, Douglas D, Pierre A, Wood E. Harm reduction by a “user-run” organization: A case study of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Ivanova I, Leyland A. Long overdue: why BC needs a poverty reductin plan. 2017 Retrieved from Vancouver, BC: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BCOffice/2017/01/ccpa-bc_long-overdue-poverty-plan_web.pdf.

- Lee M. Getting serious about affordable housing: towards a plan for metro Vancouver. 2016 Retrieved from Vancouver, BC: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BCOffice/2016/05/CCPA-BC-Affordable-Housing.pdf.

- Linton SL, Jennings JM, Latkin CA, Kirk GD, Mehta SH. The association between neighborhood residential rehabilitation and injection drug use in Baltimore, Maryland, 2000–2011. Health & Place. 2014;28(Supplement C):142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas B, Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Neighborhood and HIV infection among IDU: Place of residence independently predicts HIV infection among a cohort of injection drug users. Health & Place. 2007;13(2):432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Kerr T, Shoveller JA, Patterson TL, Buxton JA, Wood E. Homelessness and unstable housing associated with an increased risk of HIV and STI transmission among street-involved youth. Health & Place. 2009;15(3):783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez AN, Lorvick J, Kral AH. Activity spaces among injection drug users in San Francisco. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Cooper H, Small W, Kerr T. Area restrictions, risk, harm, and health care access among people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada: A spatially oriented qualitative study. Health Place. 2015;35:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Kerr T, Anderson S, Maher L, Keewatin C, Milloy MJ, Small W. Negotiating structural vulnerability following regulatory changes to a provincial methadone program in Vancouver, Canada: A qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Shannon K, Shaver L, Kerr T, Small W. Negotiating place and gendered violence in Canada’s largest open drug scene. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W. ‘Safer Environment Interventions’: A qualitative synthesis of the experiences and perceptions of people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, Kerr T. People Knew They Could Come Here to Get Help”: An Ethnographic Study of Assisted Injection Practices at a Peer-Run ‘Unsanctioned’ Supervised Drug Consumption Room in a Canadian Setting. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):473–485. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0540-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PG. Scapegoating, self-confidence and risk comparison: The functionality of risk neutralisation and lay epidemiology by injecting drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(4):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin S, Coomber R. Informal ‘Sorter’ Houses: A qualitative insight of the ‘shooting gallery’ phenomenon in a UK setting. Health & Place. 2009;15(4):981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin M, Pollini RA, Ramos R, Lozada R, Brouwer KC, Ramos ME, Strathdee SA. Shooting gallery attendance among IDUs in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico: correlates, prevention opportunities, and the role of the environment. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4):552–560. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9372-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural Vulnerability and Health: Latino Migrant Laborers in the United States. Medical anthropology. 2011;30(4):339–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos R, Ferreira-Pinto JB, Brouwer KC, Ramos ME, Lozada RM, Firestone-Cruz M, Strathdee SA. A tale of two cities: Social and environmental influences shaping risk factors and protective behaviors in two Mexico–US border cities. Health & Place. 2009;15(4):999–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Kimber J, Small W, Fitzgerald J, Kerr T, Hickman M, Holloway G. Public injecting and the need for ‘safer environment interventions’ in the reduction of drug-related harm. Addiction. 2006;101(10):1384–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee SA, Shannon K, Davidson P, Bourgois P. Structural Violence and Structural Vulnerability Within the Risk Environment: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives for a Social Epidemiology of HIV Risk Among Injection Drug Users and Sex Workers. In: O’Campo P, Dunn JR, editors. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Towards a Science of Change. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012. pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Watts L, Davies S, Martin A, Smith J, Clark D, Lyons M. Risk, shame and the public injector: a qualitative study of drug injecting in South Wales. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):572–585. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheim A, Rachlis B, Bardwell G, Mitra S, Kerr T. Public drug injecting in London, Ontario: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(2):E290–E294. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D. Visual ethnography: Using photography in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology. 1989;12(2):119–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00988995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Ishida T, Lai C, Tyndall MW. The impact of unregulated single room occupancy hotels on the health status of illicit drug users in Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Rusch M, Kerr T, Tyndall MW. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):659–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler A, Tuazon E, Bradley O’Brien D, Paone D. Unintentional opioid overdose deaths in New York City, 2005-2010: a place-based approach to reduce risk. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: Evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Rhodes T, Wood E, Kerr T. Public injection settings in Vancouver: Physical environment, social context and risk. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strike C, Guta A, de Prinse K, Switzer S, Chan Carusone S. Living with addiction: The perspectives of drug using and non-using individuals about sharing space in a hospital setting. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):640–649. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szott K. Remaking hospital space: the health care practices of injection drug users in New York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):650–652. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, McQuie H. Drugscapes and the role of place and space in injection drug use-related HIV risk environments. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin KE, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin CA. Social-level correlates of shooting gallery attendance: a focus on networks and norms. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1142–1148. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9670-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweed EJ, Rodgers M. Taking away the chaos: The health needs of people who inject drugs in public places in Glasgow city centre. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5718-9. Retrieved from Glasgow: http://www.nhsggc.org.uk/media/238302/nhsggc_health_needs_drug_injectors_full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- van Beek I. The Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre: A Clinical Model. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(3):625–638. doi: 10.1177/002204260303300305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B, Barber K, Pauly B. Sheltering risks: Implementation of harm reduction in homeless shelters during an overdose emergency. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2018;53:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J, Linssen L, de Graaf I. Drug Consumption Facilities in the Netherlands. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(3):649–661. doi: 10.1177/002204260303300307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Marsh DC, Montaner JSG, Tyndall MW. Changes in public order after the opening of a medically supervised safer injecting facility for illicit injection drug users. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2004;171(7):731–734. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]