Abstract

We sought to examine risk and protective factors for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among African American women living with HIV. This is a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from a randomized trial of an HIV stigma reduction intervention. We examined data from two-hundred and thirty-nine African American women living with HIV. We examined whether age, marital status, level of education, internalized HIV-related stigma, and social support as potential protective and risk factors for PTSD symptoms using logistic regression. We analyzed bi-variate associations between each variable and PTSD symptoms, and constructed a multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for all variables. We found 67% reported clinically significant PTSD symptoms at baseline. Our results suggest that age, education, and internalized stigma were found to be associated with PTSD symptoms (p<0.001), with older age and more education as protective factors and stigma as a risk factor for PTSD. Therefore, understanding this relationship may help improve assessment and treatment through evidence-based and trauma-informed strategies.

Introduction

In the United States, over 1.2 million people were living with HIV (PLWH) by the end of 2015 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Women account for 27% of all new HIV/AIDS diagnoses in the United States (Machtinger, Wilson, Haberer, & Weiss, 2012). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that there 40,000 new HIV diagnoses in 2015, and among these women, 61% were African American, 19% were white and 15% were Hispanic/Latina (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2015). This disproportional burden of HIV on a vulnerable segment of American society is rooted in systematic and structural factors that are influenced by poverty, education, and historical neglect of this community (Wolde-Yohannes, 2012).

HIV and PTSD

Exposure to traumatic events and developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) predisposes women to poor health outcomes, such as HIV (El-Bassel, Gilbert, Witte, Wu, & Vinocur, 2010; Machtinger et al., 2012). A growing body of research has shown that women in the US who have been diagnosed with PTSD are at higher risk for acquiring HIV (Machtinger et al., 2012). Ten percent of women develop PTSD in their lifetime, compared to 4% of men (NCPTSD, 2017). For African American women, experiencing trauma may increase the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors including unsafe sexual practices and risky substance use. Women living with PTSD are more likely to engage in high HIV risk behaviors, such as having multiple intimate partners, frequent sex trade, and reduced condom use (Morrill, Kasten, Urato, & Larson, 2001). In addition, over one third of African American women have symptoms of PTSD (Brownley, Fallot, Wolfson Berley, & Himelhoch, 2015). Additional comorbidities add to the burden of PTSD, for example, 94% of African American women with substance use disorder reported having at least one trauma exposure per lifetime, and over 51% met the DSM IV criteria for PTSD diagnosis (Meshberg-Cohen, Presseau, Thacker, Hefner, & Svikis, 2016).

Research shows that African American women experience high rates of trauma (Catalano & Statistician, 2013), and are less likely to pursue treatment for their PTSD than white individuals (Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011). PTSD impacts the quality of life of those living with HIV, and leads to poor health management (Gonzalez et al., 2016), exacerbating poor outcomes for this vulnerable population. Examining risk and protective factors for PTSD symptoms among women who live with HIV is important to help develop evidence-based intervention with high-risk individuals (Martinez, Israelski, Walker, & Koopman, 2002).

HIV Resiliency Factors

It is estimated that adults aged 50 years and older represent 50% of People Living with HIV (PLWH) in the US (Beaulaurier, Fortuna, Lind, & Emlet, 2014). Age is strongly associated with perceived HIV-related stigma, largely due to feelings of being an unvalued member of one’s community (Cuca et al., 2017). Even after experiencing oppression and hardship, middle-aged and older African American women living with HIV demonstrate the ability to endure and adapt by sustaining any support that’s available to them (Subramaniam, et al., 2016).

The ability to obtain education influences the level of information or knowledge about HIV transmission. Overall level of knowledge about HIV infection is low among high risk African American individuals, and obtaining higher education beyond high school has been identified as a protective factor (Klein, Sterk, Elifson, 2016). Overall, women who have been living with HIV for longer periods report that having support from relationships with family, friends, and partners contributes to their resilience and ability to manage and live with this chronic disease (Emlet, Tozay, & Raveis, 2011).

Social support, such as the support offered by family, spouses, and peers, provides an important coping mechanism for women living with HIV (Davtyan, et al., 2016). Edwards and colleagues found that African American women’s perceptions of positive support includes having partners or children and having a caring family (Edwards, 2006). Women between ages 52–65 also identify needing peer social support and having emotionally supportive health care providers for better long-term outcomes with their care (Warren-Jeanpiere, Dillaway, Hamilton, Young, & Goparaju, 2017). There’s great utility in assessing and identifying strategies of coping in traumatic situations, and in this case with PTSD symptoms related to HIV. Researchers have found that African American women use various strategies to cope, such as utilizing social support, use of religious or spiritual support, or avoidance in some cases (Sullivan, Weiss, Price, Pugh, & Hansen, 2017).

Stigma and PTSD

Edwards (2016) found that African American women self-reported that feeling isolated and stigmatized can negatively impact patient’s ability to adhere to medications and engagement in health care. Stereotypes and negative interpretations of HIV perpetuated by people in their communities can lead to a fear of intimate relationships and nondisclosure of their HIV status, leading to potential further spread of HIV (Cole, Logan, & Shannon, 2007; Lang et al., 2003). However, studies have not yet examined the relationship between HIV-related stigma and PTSD may share common causes and consequences for adherence and engagement in care.

There is an urgent need for understanding these factors to inform targeted and culturally-appropriate interventions to address the complex nexus of trauma, HIV infection risk, and positive coping skills for living with HIV. In this study, we examine the risk and protective factors of PTSD among African American women living with HIV.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was nested within a larger randomized clinical trial. We used HIV data collected at baseline about the participants age, education, marital status, social support, and HIV related stigma, and further assessed whether they are associated with significant symptoms of PTSD for those African American women living with HIV.

Participants

Eligible study participants met the following criteria: (1) self-identified as having African American racial/ethnic background, (2) were at least 18 years of age or older, and (3) had a documented HIV positive status. Women who identified as African American but were not born in the United States were not included in the study.

Setting

We recruited participants from a total of three sites, including two university and hospital-affiliated HIV clinics in Chicago, Illinois and one in Birmingham, Alabama. We recruited participants via signs that were posted at HIV/Infectious Diseases clinics to advertise the study and research assistants met potential participants during clinic visits. Data were gathered in office spaces within the clinics to maximize convenience for participants who were attending clinic visits.

Procedures

Research assistants described study procedures to participants to ensure clear understanding of the purpose of the study. Participants then provided written informed consent before study measures were implemented. The data for this study were collected using an Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI) System (The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group, 2007). This system was chosen because it ensured that participants had privacy, and helped those with limited literacy comprehend the study questions (Pluhar et al., 2007).

Measures

We analyzed socio-demographic (age, marital status, level of education) and psychosocial (level of internalized HIV-related stigma, social support, PTSD) variables for this study. We analyzed age as a continuous variable, educational level as a dummy variable from “Less than HS” to “College degree or above”, and marital status as a dummy variable from “Never Married” to “Separated or divorced”. We collected and analyzed the psychosocial variables as described below.

Internalized Stigma.

We examined levels of internalized, HIV-related stigma using the 14-item version of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness. The scale has been adapted and validated for use with African Americans living with HIV (Rao et al., 2012; Rao, Molina, Lambert, & Cohn, 2016). The scale included questions such as: “because of my illness, I felt different from others” and “I felt embarrassed about my illness” with Likert-type response choices. The scale demonstrated good psychometric properties with a sample of African Americans living with HIV (Rao et al., 2016). We summed and mean imputed the item responses to form a total score ranging from 0 to 44.

Social Support.

We measured Social Support using the 19-item Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey, to assess perceived social support in relation to HIV status (Robitaille, Orpana, & McIntosh, 2011). Women were asked questions about what type of support they had available with questions such as: “someone to give you good advice about a crisis” or “someone to share your most private worries and fears with” with Likert-type response choices. We summed and mean imputed the item responses, and the to form a total score ranging from 0 to 70.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms.

We assessed the participants’ symptoms of PTSD using the PTSD checklist (Kessler et al., 2011). The PTSD checklist used all 17 items (with Likert-type response choices) corresponding to DSM-IV symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This checklist was validated for use in primary care settings to quantify PTSD symptoms (Lang et al., 2012). Symptoms of PTSD such as: “feeling distant or cut off from other people?” or “repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience from the past?” were assessed. We summed and mean imputed the items to form the total score. A cutoff of 30 or higher (out of 85) indicated a clinically-significant level of PTSD, and this cutoff was used to categorize this data into “low vs. high PTSD” symptom groups (Lang et al., 2012).

Statistical Analysis

We examined age, marital status, level of education, stigma and social support as independent variables and PTSD symptoms as the dependent variable, using logistic regression. We first analyzed the bi-variate associations between each variable alone and PTSD symptoms. We then constructed a multi-variable model which controlled for all variables simultaneously. Analyses were conducted using Stata 14 and an alpha value for statistical significance of α=0.05 using two-tailed tests (StataCorp, 2015). Significance of categorical variables was determined by likelihood-ratio tests.

Results

Background Information

Two hundred and thirty-nine women completed baseline assessments. One hundred and thirty-two women received HIV care in Chicago, IL and 107 in Birmingham, AL. Table 1 lists means and frequencies for the socio-demographic variables for all participants, separated by clinically significant high and low PTSD levels. Mean age was 46.7 years (SE=10.5). For the Education category, 37% had “less than High School (HS)”, 23% had “HS degree or equivalent”, 29% had “some college or technical degree”, and 8% had “college degree or above”.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Information

| Characteristics | Total; n (%) unless noted |

PTSD High (≥30); n (%) unless noted |

PTSD Low (≤29); n (%) unless noted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 239 (100) | 160 (67.0) | 79 (33.1) |

| Factor Variables | |||

| Age | |||

| 18–35 | 38 (15.9) | 28 (73.7) | 10 (26.3) |

| 36–45 | 71 (29.7) | 54 (76.1) | 17 (24.0) |

| 46–55 | 81 (33.9) | 51 (63.0) | 30 (37.0) |

| 56+ | 49 (20.5) | 27 (55.1) | 22 (44.9) |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS | 89 (37.2) | 72 (80.9) | 17 (19.1) |

| HS degree or equivalent | 55 (23.0) | 35 (64.0) | 20 (36.4) |

| Some college / technical degree | 70 (29.3) | 40 (57.1) | 30 (43.0) |

| College degree or above | 19 (7.94) | 10 (53.0) | 9 (47.4) |

| Missing | 6 (2.51) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Never been married | 85 (35.6) | 64 (75.3) | 21 (25.0) |

| Married or Living with Partner | 56 (23.4) | 35 (63.0) | 21 (38.0) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 97 (40.6) | 61 (63.0) | 36 (37.1) |

| Missing | 1 (0.41) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Social Support (Mean; 95% CI) | 30.6 (29.0, 32.1) | 29.1 (27.2, 31.0) | 33.6 (30.9, 36.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.41) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Internalized Stigma (Mean; 95% CI) | 13.8 (13.0, 14.6) | 16.0 (15.0, 17.0) | 9.3 (8.5, 10.1) |

| Missing | 1 (0.41) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) |

In terms of participant’s marital status, 23% were married or living with partner, 41% were separated divorced or widowed, and 36% never had been married. A total of 67% of the women reported clinically significant PTSD symptoms (total scores of >30 out of 85). Rates of missing data was low and didn’t impact the overall analysis, see table 1.

Unadjusted Regression Models

Table 2 presents the results of the unadjusted and adjusted regression models. Age was significant in the unadjusted regression model, with each 1-year increase in age associated with decreasing odds of PTSD (Odds ratio [OR]: 0.97; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.95, 0.99).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Statistics

| Characteristics |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Factor Variables | ||||

| Education* | ||||

| Less than HS | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| HS degree or equivalent | 0.41 (0.19, 0.89) | 0.02 | 0.43 (0.17, 1.07) | 0.07 |

| Some college / technical degree | 0.31 (0.15, 0.64) | 0.001 | 0.26 (0.11, 0.63) | 0.003 |

| College degree or above | 0.26 (0.09, 0.75) | 0.01 | 0.27 (0.08, 0.96) | 0.04 |

| Marital Status* | ||||

| Never been married | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Married or Living with Partner | 0.55 (0.26, 1.1) | 0.11 | 0.45 (0.18, 1.19) | 0.11 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 0.56 (0.29, 1.1) | 0.07 | 0.88 (0.39, 1.99) | 0.76 |

| Continuous variables | ||||

| Age (OR; 95% CI) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.04 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.43 |

| Social Support (OR; 95% CI) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.008 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.59 |

| Internalized Stigma (OR; 95% CI) | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.20, 1.42) | <0.001 |

Overall significance of factor variables in adjusted model by likelihood ratio test:; education p-value: 0.013; marital status p value: 0.24

Education was also significantly associated with PTSD scores (p<0.01), with lower levels of education being associated with increased odds of high PTSD symptoms. For example, the odds of high PTSD symptoms for those with a high school education was significantly lower than those who had less than a high school education (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.19, 0.89). Individuals with a college degree or above had even lower odds of high PTSD symptoms compared to those with a high school education or less (OR: 0.26; CI: 0.09, 0.75).

Marital status was not significantly associated with the odds of high PTSD (p=0.13). Social support was significantly associated with PTSD symptoms in the unadjusted model, showing a protective effect (p<0.01). For each 1-unit increase in the social support scale, the odds of high PTSD decreased by 3% (OR: 0.97, CI: 0.94, 0.99). Internalized stigma was significantly associated with PTSD (p<0.001); for each 1-unit increase in the internalized sigma scale, the odds of high PTSD increased by 30% (OR: 1.3; CI: 1.2, 1.4).

Adjusted Regression Model

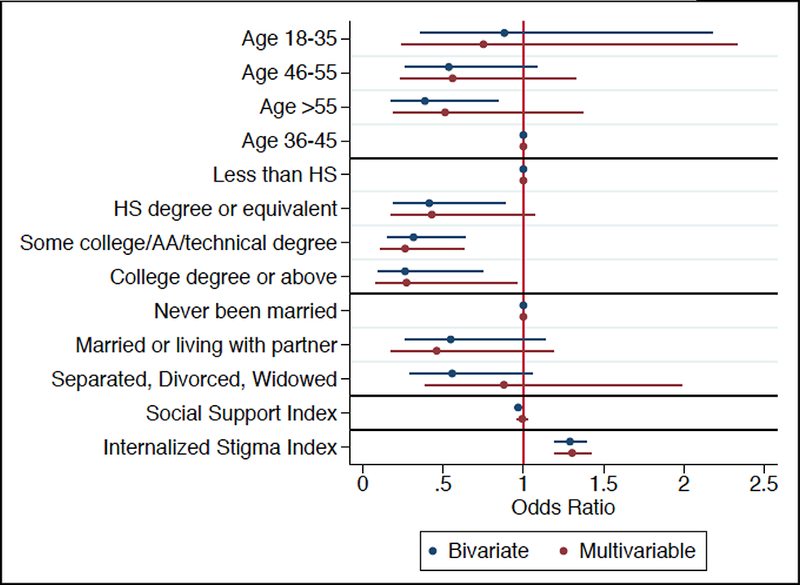

Adjusted model estimates are summarized in Figure 1. In the adjusted model, age was not a significant predictor of PTSD in our cross-sectional data. Levels of education were a significant protective factor against high PTSD symptoms (p<0.01), with odds of high PTSD decreased with increasing levels of education. For example, those who completed some college having lower odds of PTSD symptoms compared to those with less than a HS education. Marital status as a factor was not significantly associated with the odds of PTSD symptoms in the adjusted regression model (p=0.24). Also, social support was not significant in the adjusted regression model (p=0.65). Finally, internalized stigma was a significant risk factor for PTSD symptoms in the adjusted regression model (p<0.001). For each 1-unit increase in internalized stigma, the odds of PTSD score > 30 increased by 30% (OR: 1.30, CI: 1.19, 1.42).

Figure 1.

Forest Plot of Odds Ratios with Confidence Intervals.

We conducted post-hoc analyses to examine the relationship between stigma and social support, to better understand if the relationship between social support and stigma led to social support’s non-significance in the adjusted model. Social support and stigma have a strong relationship. An exploratory linear regression comparing social support to internalized stigma showed that for each 1-unit increase in social support, internalized stigma decreased by −0.5 (CI: −0.73, −0.27, p<0.001).

Discussion

We found high rates of clinically-significant PTSD symptoms among African American women living with HIV. Several other studies have found similarly high levels of PTSD among African American women (Glover, Williams, & Kisler, 2013; Siyahhan Julnes et al., 2016; Whetten, Reif, Whetten, & Murphy-McMillan, 2008). Our study suggests that age, education, internalized stigma, and social support are associated with significant PTSD symptoms. Age was associated with higher PTSD symptoms, where women with older age had lower symptoms of PTSD. When further examining age, our study found significant associations with PTSD symptoms. However, based on point estimates alone, our results suggest that older women may be less likely to have high PTSD symptoms. This is consistent with findings from Subramaniam et al., 2016, that older African American women can adapt when faced with adversity and oppression. This may be due to their increased social support despite their lived experiences of trauma and discrimination. The younger age category in our sample seemed to have increased odds of PTSD; this may be due to various challenges such as self-esteem, rejection, HIV disclosure, and lack of coping and adaptability skills as previously found in a study done to understand the impacts of HIV on younger women (Hosek, Brothers, Lemos, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, 2012).

Education was a protective factor, and increased education was significantly associated with lower PTSD symptoms. This is again consistent with what other studies have found (Bynum et al., 2016). Education may provide access to more economic gains in terms of financial stability, and in contrast, women who live in low income neighborhoods with high crime levels are more exposed to substance use and violence (El-Bassel et al., 2009).

In unadjusted analyses, social support was found to be significantly associated with PTSD as a protective factor. As social support increases, PTSD decreases among HIV-positive women. Since we can’t know the directionality of this effect, further research can explain whether this is likely due to having support from family and friends in their communities, or if there are other factors that influence this outcome. However, in the adjusted model, social support was no longer significantly associated with PTSD symptoms. Our post-hoc analyses suggest that social support has a strong inverse relationship with internalized stigma, the strongest associated factor in adjusted analyses. We hypothesize that lack of social support may be on the pathway to the development of high levels of internalized stigma, which are very strongly related to high PTSD in this population. These findings are consistent with studies that have linked social support as a mechanism to reduce stigma in non-HIV contexts (Corrigan, Sokol, & Rüsch, 2013; Whitley & Denise Campbell, 2014).

We had several limitations in this study. The was a cross-sectional study and therefore we were not able to draw causal inference about the associations that were found in the results. Furthermore, we did not measure the type of trauma to which the participants were exposed, and thus we were not able to examine how different types of trauma may affect PTSD and its risk and protective factors. Had they been available, including other variables such as substance use history, psychotropic medication use, history of mental health treatment, antiretroviral therapy (ART) and viral load history, and other sociodemographic factors would have added additional insight to our findings. Since this study focused primarily on the experiences of African American women, we cannot generalize the findings to all HIV infected individuals.

These limitations notwithstanding, this study had several strengths. First, since this analysis represents one of the few studies to examine risk and protective factors for mental health status of African American women living with HIV. Overall, we found that age, social support, and education may be associated with resiliency factors to help reduce risk of PTSD. Future studies can further explore this relationship and its impact on adherence to antiretroviral therapy care, and HIV care further assessment is needed on how to increase resilience for those living with HIV to improve their adherence and health outcomes.

Conclusion

HIV and PTSD continue to cause significant burden disease burden in the US, and disproportionally impacts African American women. Our study found that age, education, social support and internalized stigma are associated with PTSD symptoms among African American women living with HIV. Our results suggest that promoting education and social support interventions may be helpful intervention strategies for reducing health disparities among African American women. Further, given the high prevalence of significant PTSD symptoms in this population, our results suggest that trauma-informed interventions may help to address recent and long-term effects of trauma experienced by African American women with HIV. Future studies are needed examine effective pathways towards prevention and intervention for African American women living with HIV.

Footnotes

This study was supported by R01 MH 098675 (PI Rao)

Contributor Information

Eaden Andu, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Brad H. Wagenaar, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Chris G. Kemp, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Paul E. Nevin, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Jane M. Simoni, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Michele Andrasik, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington.

Susan E. Cohn, Department of Infectious Diseases, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois

Audrey L. French, Ruth M. Rothstein, Core Center, Chicago, Illinois

Deepa Rao, Department of Global Health/Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

References

- Beaulaurier R, Fortuna K, Lind D, & Emlet CA (2014). Attitudes and Stereotypes Regarding Older Women and HIV Risk. 10.1080/08952841.2014.933648 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brownley JR, Fallot RD, Wolfson Berley R, & Himelhoch SS (2015). Trauma history in African-American women living with HIV: effects on psychiatric symptom severity and religious coping. AIDS Care, 27(8), 964–971. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1017441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum SA, Wigfall LT, Brandt HM, Julious CH, Glover SH, & Hébert JR (2016). Social and Structural Determinants of Cervical Health among Women Engaged in HIV Care. AIDS and Behavior, 20(9), 2101–2109. 10.1007/s10461-016-1345-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S, & Statistician B (2013). Intimate Partner Violence: Attributes of Victimization, 1993–2011. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipvav9311.pdf

- Centar for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment--United States. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(47), 1618–23. https://doi.org/mm6047a4 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2015). Women | Gender | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC. Retrieved June 23, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html

- Cole J, Logan TK, & Shannon L (2007). Risky sexual behavior among women with protective orders against violent male partners. AIDS and Behavior, 11(1), 103–112. 10.1007/s10461-006-9085-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Sokol KA, & Rüsch N (2013). The impact of self-stigma and mutual help programs on the quality of life of people with serious mental illnesses. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(1), 1–6. 10.1007/s10597-011-9445-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuca YP, Asher A, Okonsky J, Kaihura A, Dawson-Rose C, & Webel A (2017). HIV Stigma and Social Capital in Women Living With HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 28(1), 45–54. 10.1016/j.jana.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davtyan M, Farmer S, Brown B, Sami M, & Frederick T (2016). Women of Color Reflect on HIV-Related Stigma through PhotoVoice. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 27(4), 404–418. 10.1016/j.jana.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LV (2006). Perceived social support and HIV/AIDS medication adherence among African American women. Qualitative Health Research, 16(5), 679–691. 10.1177/1049732305281597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Caldeira NA, Ruglass LM, & Gilbert L (2009). Addressing the unique needs of African American women in HIV prevention. American Journal of Public Health. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, & Vinocur D (2010). African Americans and HIV/AIDS. African Americans and HIV/AIDS: Understanding and Addressing the Epidemic. 10.1007/978-0-387-78321-5 [DOI]

- Emlet CA, Tozay S, & Raveis VH (2011). "I’m Not Going to Die from the AIDS": Resilience in Aging with HIV Disease. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 101–111. 10.1093/geront/gnq060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover DA, Williams JK, & Kisler KA (2013). Using novel methods to examine stress among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(3), 283–294. 10.1007/s10865-012-9421-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Locicero B, Mahaffey B, Fleming C, Harris J, & Vujanovic AA (2016). Internalized HIV Stigma and Mindfulness: Associations With PTSD Symptom Severity in Trauma-Exposed Adults With HIV/AIDS. Behavior Modification, 40(1–2), 144–163. 10.1177/0145445515615354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, Sterk C, Elifson K (2016). Knowledge about HIV in a Community Sample of Urban African Americans in the South. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 7(10). 10.4172/2155-6113.1000622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosek S, Brothers J, Lemos D, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2012). What HIV-positive young women want from behavioral interventions: a qualitative approach. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 26(5), 291–7. 10.1089/apc.2011.0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin K a, Green JG, Russo LJ, … Ustün TB (2011). Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(1), 90–100. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Rodgers CS, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Dresselhaus TR, & Stein MB (2003). Sexual Trauma, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Health Behavior. Behavioral Medicine, 28(4), 150–158. 10.1080/08964280309596053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Wilkins K, Roy-Byrne PP, Golinelli D, Chavira D, Sherbourne C, ... Stein MB (2012). Abbreviated PTSD Checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(4), 332–8. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LCOD Black Females 2014 - Women’s Health - CDC. (2014). Retrieved June 1, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/2014/black/index.htm

- Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, & Weiss DS (2012). Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 16(8), 2091–2100. 10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Israelski D, Walker C, & Koopman C (2002). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Women Attending Human Immunodeficiency Virus Outpatient Clinics. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 16(6), 283–291. 10.1089/10872910260066714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshberg-Cohen S, Presseau C, Thacker LR, Hefner K, & Svikis D (2016). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Health Problems, and Depression Among African American Women in Residential Substance Use Treatment. Journal of Women’s Health, 25(7), 729–737. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill AC, Kasten L, Urato M, & Larson MJ (2001). Abuse, addiction, and depression as pathways to sexual risk in women and men with a history of substance abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(1–2), 169–84. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11547617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCPTSD. (2017). How Common Is PTSD? - PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Retrieved May 25, 2017, from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/ptsd-overview/basics/how-common-is-ptsd.asp

- Pluhar E, McDonnell Holstad M, Yeager KA, Denzmore-Nwagbara P, Corkran C, Fielder B, … Diiorio C (2007). Implementation of audio computer-assisted interviewing software in HIV/AIDS research. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC, 18(4), 51–63. 10.1016/j.jana.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Desmond M, Andrasik M, Rasberry T, Lambert N, Cohn SE, & Simoni J (2012). Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy of the Unity Workshop: An Internalized Stigma Reduction Intervention for African American Women Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 26(10), 614–620. 10.1089/apc.2012.0106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Molina Y, Lambert N, & Cohn SE (2016). Assessing stigma among African Americans living with HIV. Stigma and Health, 1(3), 146–155. 10.1037/sah0000027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, & Koenen KC (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41(1), 71–83. 10.1017/S0033291710000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille A, Orpana H, & McIntosh CN (2011). Psychometric properties, factorial structure, and measurement invariance of the English and French versions of the Medical Outcomes Study social support scale. Health Reports / Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Health Information = Rapports Sur La Sant?? / Statistique Canada, Centre Canadien D’information Sur La Sant??, 22(2), 33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siyahhan Julnes P, Auh S, Krakora R, Withers K, Nora D, Matthews L, … Kapetanovic S (2016). The Association Between Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Markers of Inflammation and Immune Activation in HIV-Infected Individuals With Controlled Viremia. Psychosomatics, 57(4), 423–430. 10.1016/j.psym.2016.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. 2015. 10.2307/2234838 [DOI]

- Subramaniam S, Camacho LM, Carolan MT, & López-Zerón G (2016). Resilience in low-income African American women living and aging with HIV. Journal of Women & Aging, 1–8. 10.1080/08952841.2016.1256735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Weiss NH, Price C, Pugh N, & Hansen NB (2017). Strategies for Coping With Individual PTSD Symptoms: Experiences of African American Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 10.1037/tra0000283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. (2007). The feasibility of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing in international settings. AIDS (London, England), 21 Suppl 2, S49–S58. 10.1097/01.aids.0000266457.11020.f0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren-Jeanpiere L, Dillaway H, Hamilton P, Young M, & Goparaju L (2017). Life begins at 60: Identifying the social support needs of African American women aging with HIV. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(1), 389–405. 10.1353/hpu.2017.0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, & Murphy-McMillan LK (2008). Trauma, Mental Health, Distrust, and Stigma Among HIV-Positive Persons: Implications for Effective Care. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(5), 531–538. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817749dc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R, & Denise Campbell R (2014). Stigma, agency and recovery amongst people with severe mental illness. Social Science & Medicine, 107, 1–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolde-Yohannes S (2012). Persisting failure to protect populations at risk from HIV transmission: African American women in the United States (US). Journal of Public Health Policy, 33(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.usc.edu/10.1057/jphp.2012.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]