Abstract

Background

The use of FDA approved medications for Alzheimer's disease [AD; FDAAMAD; (cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists)] has been associated with symptomatic benefit with a reduction in formal (paid services) and total costs of care (formal and informal costs). We examined the use of these medications and their association with informal costs in persons with dementia.

Method

Two hundred eighty participants (53% female, 72% AD) from the longitudinal, population-based Dementia Progression Study in Cache County, Utah (USA) were followed up to 10 years. Mean (SD) age at baseline was 85.6 (5.5) years. Informal costs (expressed in 2015 dollars) were calculated using the replacement cost method (hours of care multiplied by the median wage in Utah in the visit year) and adjusted for inflation using the Medical Consumer Price Index. Generalized Estimating Equations with a gamma log-link function, were used to examine the longitudinal association between use of FDAAMAD and informal costs.

Results

The daily informal cost for each participant at baseline ranged from $0 to $318.12, with the sample median of $9.40. Within the entire sample, use of FDAAMAD was not significantly associated with informal costs (expβ = .73, p = .060). In analyses restricted to participants with mild dementia at baseline (N = 222), use of FDAAMAD was associated with 32% lower costs (expβ = .68, p = .038).

Conclusions

Use of FDAAMAD was associated with lower informal care costs in those with mild dementia only.

Introduction

Estimates suggest that family caregivers provide about 83% of home care for people with dementia (Alzheimer's Association, 2016). In the US in 2015, an estimated 18.1 billon hours of informal care was provided to persons with dementia, which was valued at $221.3 billion (2015 US dollars) (Alzheimer's Association, 2016). There is a limited body of literature on the informal costs of dementia care in the US. The Asset and Health Dynamics (AHEAD) Study, which studied a representative US sample of 7,443 community-dwelling individuals age 70 years or older, provided informal cost estimates based on cross-sectional data. The informal cost of dementia care was estimated via the replacement cost method, employing the 1998 national average wage for a home heath aid (mean wage of $8.20 per hour) (Langa et al., 2001). For mild dementia, the estimated annual informal cost per person was $3,630 overall, but $17,700 for severe dementia (in 2001 dollars) (Langa et al., 2001). Employing wages of home health aides at the 10th percentile ($5.90 per hour) and at the 90th percentile ($10.80 per hour), informal costs for mild dementia were estimated at $2,610 per person, per year (PPPY) and for severe dementia at $12,730 PPPY for wages at the 10th percentile; estimates for wages at the 90th percentile were $4,780 PPPY for mild dementia and $23,310 PPPY for severe dementia (Langa et al., 2001).

A more recent cross-sectional study estimated informal care costs using two methods, forgone wages and replacement wages, in a nationally representative US sample from the Health and Retirement Study [HRS, (Hurd et al., 2013)]. Use of forgone wages to estimate informal costs bases the cost estimates on actual wages of the caregivers who are giving up time at their jobs to assist the individual with dementia. For employed caregivers, foregone wages were based on the their self-reported wage and for caregivers who were not employed, forgone wages were calculated as the average of the wages for persons with similar demographic characteristics (age, gender, and education level) (Hurd et al., 2013). Replacement costs of informal care were calculated by using the market cost of the equivalent services purchased through a home health agency. After controlling for comorbidities, annual costs based on forgone wages were estimated at $41,689 per person [with 95% Confidence Interval (CI), $31,017 to $52,362] with those based on replacement costs estimated at $56,290 (with 95% CI, $42,746 to $69,834) in 2010 dollars (Hurd et al., 2013). It was estimated that 31% (using foregone wages) to 49% (using replacement costs) of the total costs of dementia care were accounted for by informal care costs (Hurd et al., 2013). Cost estimates by dementia severity were not available in this cross-sectional analysis.

Two US longitudinal studies examined the informal costs of dementia care by symptom severity. The Predictors Study enrolled 204 persons with Alzheimer's disease (AD) from three university-based research clinics and followed them longitudinally from 1990 to 2004 (Zhu et al., 2006a). Informal costs were estimated by taking the national average of hourly earnings in private industries for each year of the study. At baseline, informal costs were estimated at US $20,589 per year and increased to US $43,030 after a four-year follow-up. This study also found that loss of one point on a measure of cognitive abilities (Mini-Mental State Exam; higher score equals greater abilities) decreased the probability of the person with AD receiving informal care by 9%, while a one point increase on a measure of daily function (Blessed Dementia Rating Scale; higher score equals greater disability) increased the probability of the person with AD receiving informal care by 29.5% (Zhu et al., 2006a). While one of the strengths of this study was the length of follow-up, the participants represented a unique sample of AD patients treated at dementia specialty clinics, which may limit generalizability of results to more typical community-dwelling persons with dementia. In the population-based Cache County Dementia Progression Study (DPS), Rattinger and colleagues used the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) to measure dementia severity. They found that compared to those with very mild dementia (CDR = .5), mild dementia increased daily costs over two-fold, moderate dementia over five-fold, and severe dementia severity over six-fold (Rattinger et al., 2015).

Factors that might reduce the informal costs of dementia care have not been well-studied. Prior work in the Cache County DPS reported a slowing in dementia progression by caregiver factors including relationship closeness (Norton et al., 2009) and use of problem-focused coping strategies (Tschanz et al., 2013). Only caregiver closeness predicted lower costs of informal care (Rattinger et al., 2016). With respect to pharmacological treatments of dementia, FDA-approved medications for AD (FDAAMAD) include the cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) tacrine, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, memantine (Namenda) (Atri, 2011), and have been associated with lower rate of dementia progression (Mielke et al., 2012) and cognitive decline in short term studies (reviewed by Rountree et al., 2013). Long-term observational studies found that persistent use of FDAAMAD reduced cognitive, functional, and global decline (Rountree et al., 2013), with combination therapy including memantine being superior to ChEI monotherapy (Rountree et al., 2013). With respect to cost, Fillit and Hill's 2005 review (Fillit and Hill, 2005) reported a reduction in total costs (formal and informal) for those treated with ChEIs of $73 for a person with mild AD and $2290 (in 1997 US dollars) for a person with moderate AD over two years' time (Fillit and Hill, 2005). Another study of 687 Medicare enrollees with mild-to-moderate dementia found that those using donepezil incurred $2500 lower mean costs of medical services per year compared to those who were not treated with FDAAMAD (Lu et al., 2005). The greater costs of those not receiving FDAAMAD primarily reflected the greater services obtained in hospitals and post-acute skilled nursing facilities, as well as, longer lengths of stay (Lu et al., 2005). However, the lower costs incurred by those taking donepezil were somewhat offset by greater costs in prescriptions, physician visits, and outpatient hospital costs (Lu et al., 2005).

The use of FDAAMAD has been shown to slow disease progression, and it has been demonstrated that slowing disease progression reduces informal costs of care. To our knowledge no US studies have examined the costs of informal dementia care by treatment with FDAAMAD. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine whether the use of FDAAMAD was associated with lower informal costs of care in the Cache County dementia cohort.

Methods

Sample

Data from the Cache County DPS (2002 – 2013) (Tschanz et al., 2011) were used. DPS enrolled and followed persons with dementia and their caregivers identified from the population-based Cache County Study of Memory and Aging [CCSMA; (Breitner et al., 1999)]. The CCSMA included permanent residents of the county aged 65 years or older in 1995, and examined the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for dementia in this US county. In Wave 1, CCSMA enrolled 5,092 (90%) of the eligible individuals (Breitner et al., 1999) and subsequently conducted three additional triennial waves of dementia screening and evaluation. Participants with dementia were identified at each wave based on a clinical assessment that consisted of a review of clinical symptoms, medical history, physical and neurological exam, and neuropsychological assessment (see Breitner et al., 1999). Information from the clinical assessment was reviewed by a neuropsychologist, geriatric psychiatrist, and the examining nurse and psychometrist, after which a preliminary diagnosis of dementia was given if symptoms met the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-III-R [DSM-III-R; (APA, 1987)]. Participants were asked to complete a brain MRI scan, laboratory tests and a physician visit, after which a panel of clinical experts reviewed all available clinical data (Breitner et al., 1999). A diagnosis of AD was given according to criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke-Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association [NINCDS-ADRDA; (McKhann et al., 1984)]. A diagnosis of Vascular Dementia (VaD) was given based on the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN) criteria (Erkinjuntti et al., 2002). Other dementia diagnoses followed standard research protocol at that time (Breitner et al., 1999).

In order to be eligible for the DPS, individuals had to be new cases of dementia diagnosed from the CCSMA and who had a caregiver who could also participate (Tschanz et al., 2011). Once eligibility was confirmed, a research nurse and psychometrist conducted in-home evaluations of the participants and their caregivers approximately every 6-8 months. The in-home evaluations consisted of neuropsychological testing, brief neurological and physical examination, assessment of functional abilities, interview of health and psychiatric conditions, medication use and assessment of the caregiver's well-being and time spent providing care (Rattinger et al., 2015; Tschanz et al., 2011). The current analyses excluded observations in which participants resided in nursing homes as residents in such facilities only incur formal costs. Of the 328 participants in DPS, 39 were excluded from the current analyses because they resided in a nursing home at baseline, five were excluded due to missing information on medications and an additional four persons were excluded due to missing clinical dementia severity ratings. The final number of participants included in the analyses was 280.

Medication Use

At each visit, medication use was recorded by the research nurse who inspected the medicine chest for each participant following methods described previously (Zandi, 2005). Because detailed information on medication use between visits was not available, medications used at consecutive visits were assumed to be taken continuously between visits. Medications were reviewed and coded using the Mosby Drug Reference System (Skidmore-Roth, 2009). Subjects were classified according to use of FDAAMAD (ChEIs or NMDA receptor antagonists) as “current users” or “not current users.” In statistical analyses, medication use was treated as a time-varying variable.

Estimating Informal Costs

The Caregiver Activity Survey [CAS; (Davis et al., 1997)] was used to estimate informal costs of dementia care. The CAS was administered to the caregiver annually at alternating (odd numbered) visits in the DPS. The CAS has a total of six items, which assess how much assistance over the last 24 hours all caregivers provided the individual with dementia (Davis et al., 1997). These tasks included communicating with the person, using transportation, eating, dressing, supervising, and looking after one's appearance (Davis et al., 1997). The items were summed together to yield total hours which were capped at 16 hours per day, allowing for eight hours of sleep, consistent with previous research (Penrod et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 2006b).

An estimate of informal costs was generated using the hours reported on the CAS using the replacement wages method. Replacement wages (Hurd et al., 2013) were calculated by assigning values to the services from the cost equivalent of the median wage of Utah workers in the year of the visit, consistent with the approach previously used in this sample (Rattinger et al., 2015). Also consistent with Rattinger et al. (2015), the Medical Consumer Price Index (MCPI) multiplier, which is based on the annual average of “medical care services” from the Urban Consumer Price Index (CPI-U), was used to account for changes in market price over the years of data collection of the study (2002-2012) (Bureau of Labor and Statistics, 2016a). For example, to convert 2002 Utah median hourly wage into 2015 dollars, the 2002 MCPI was calculated by dividing the 2015 CPI-U annual average of 476.171 by the 2002 CPI-U annual average of 292.9 (476.171/292.9 = 1.626). The resulting value (1.626) was multiplied by the 2002 median Utah hourly wage of $12.23 totaling $19.88 (Bureau of Labor and Statistics, 2016a; b).

Covariates

Use of psychotropic medications and medications with anticholinergic properties were included as covariates in models due to their potential effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms or cognition, either of which in turn may affect informal costs (Carriere et al., 2009). Psychotropic medications included antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics. Medications with anticholinergic properties were classified using the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale [ACBS; (Campbell and Boustani, 2012)], with a score of 1 indicating possible anticholinergic effect and scores of 2 and 3 as having anticholinergic effects. Use of medications with anticholinergic properties was then classified as little to none (0 or 1) or likely (2 or 3) anticholinergic effects, and entered as a time-varying covariate in statistical models.

Additional covariates included severity of dementia and health status. The former was assessed using the Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR; (Hughes et al., 1982; O'Bryant et al., 2010)] which stages severity of dementia according to functioning in six domains: memory, orientation, judgement and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies and personal care. We used an extended version with ratings ranging from 0 (no impairment) to 5 (terminal) (Dooneief et al., 1996). The interpretation of scores from 0 to 3 are similar to the original version, but ratings of 4 and 5 extend the ceiling of the measure. Individual ratings were converted into a global score based on an algorithm (Burke et al., 1988). Additionally, CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) was calculated by summing the domain scores to create a total score ranging from 0 to 30. The CDR global score was used for staging purposes and the CDR-SB was used as a time-varying covariate of functional progression in statistical models. Overall health status was assessed using the General Medical Health Rating (GMHR), which provided a global rating of the participant's health at each visit. Due to the low frequency of persons rated in “poor health”, participants were collapsed into the following groups: “poor or fair,” “good,” and “excellent” (Lyketsos et al., 2005). GMHR was selected as a measure of medical comorbidity as previous analyses in this sample found GMHR to predict dementia progression (Leoutsakos et al., 2012). Other covariates tested in statistical models included place of residence and gender.

Statistical Analysis

Using generalized estimating equations (GEEs), we examined the association between FDAAMAD use and the informal costs of dementia care over time. All variables, except for gender, were time-varying (current medication use, CDR-SB, etc.). Variables with significant Wald values were retained (alpha = .05).

As cost distributions are highly positively skewed, a gamma distribution with, a logarithmic link function was applied to a transformation of the dependent variable (Cost + $.01, to address values of 0). This approach was previously applied to the DPS data when estimating costs (Rattinger et al., 2015). To facilitate interpretation, parameter estimates from log link models were exponentiated. For example, a hypothetical result might be that AD has an estimated beta of approximately 0.65 compared to the reference category of other dementias. Exponentiating this estimated beta (Exp(β)) yields a value of 2, which indicates that the cost for a person with AD is twice that of persons with other dementias (Rattinger et al., 2015). Because FDAAMAD are most effective when initiated early in the course of dementia (Atri, 2011), we ran GEE models utilizing the full sample and again in a restricted sample to those with a baseline global CDR score corresponding to mild dementia (CDR = 0.5 or 1.0). Covariates tested in these models were similar to those tested in analyses using the entire sample.

Results

There were 280 participants in the full sample, the majority (72%) of whom were affected by AD. At baseline, daily informal costs ranged from $0 to $318.12, with a median of $9.40. Baseline CDR ratings indicated that 79.3% of participants were mild, 16.1% were moderate, and 4.6% were severe in degree of dementia severity. Participants began use of FDAAMAD at a mean age of 82.33 (SD=5.81) years. Baseline characteristics varied by dementia type (AD vs other dementia), gender, place of residence, health status, age at dementia onset, and age (see Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Sample: AD Versus Not AD.

| Characteristics | AD (N = 202) | Not AD (N = 78) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | M | SD | n | % | M | SD | χ2 | t | |

| Female | 114 | 56.8 | 34 | 43.6 | 3.73* | |||||

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Home | 149 | 73.8 | 67 | 85.9 | 4.70* | |||||

| Assisted Living | 53 | 26.2 | 11 | 14.1 | ||||||

| Use of Antidementia Meds | 45 | 22.6 | 10 | 12.8 | 3.38 | |||||

| Use of Psychotropic Meds | 106 | 53.3 | 39 | 50.0 | .24 | |||||

| Use of Anticholinergic Meds | 38 | 18.8 | 18 | 23.1 | .64 | |||||

| GMHR Health+ | ||||||||||

| Fair/Poor | 30 | 14.9 | 22 | 28.2 | 6.64** | |||||

| Good/Excellent | 172 | 85.1 | 56 | 71.8 | ||||||

| CDR+ | ||||||||||

| Mild | 158 | 78.2 | 64 | 82.1 | .50 | |||||

| Mod./Sev. | 44 | 21.8 | 14 | 17.9 | ||||||

| Age at Baseline | 86.2 | 5.7 | 84.0 | 4.9 | 3.01** | |||||

| Education | 13.4 | 2.9 | 13.5 | 2.6 | -0.12 | |||||

| Age at Dementia Onset | 82.8 | 5.9 | 80.7 | 5.2 | 2.71** | |||||

| Dementia Duration in Years | 3.4 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 1.6 | .49 | |||||

| Daily Cost in Utah | 40.58 | 80.01 | 47.76 | 84.91 | -.66 | |||||

Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the sample, highlighting differences in participants with AD compared to participants with other dementia.

Significant differences between at p<=.05.

Significant differences between at p<=.01.

Note these covariates were further collapsed into dichotomous variables because of low frequency in the severe CDR and Poor or Excellent GMHR cells.

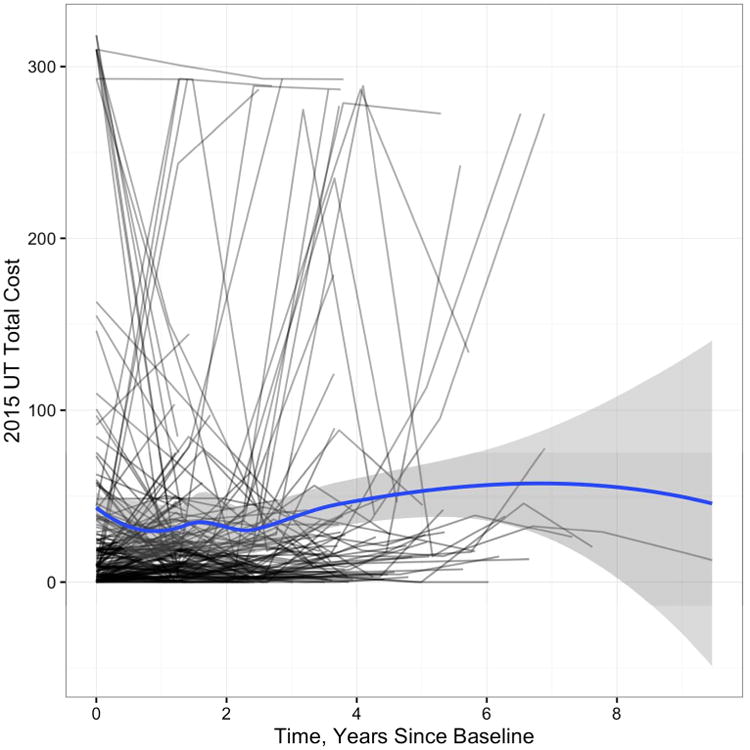

Substantial variability in costs over time was evident in the sample. Figure 1 displays person specific trajectories of informal costs over time, with the blue line indicating the moving average or general trend of the data and the shaded grey region indicating the 95% confidence band. There were 180 participants who had informal daily costs below $20 at baseline and an additional 63 participants with informal costs between $20 to $100.

Figure 1. Person-Specific Plot of Daily Cost Over Time.

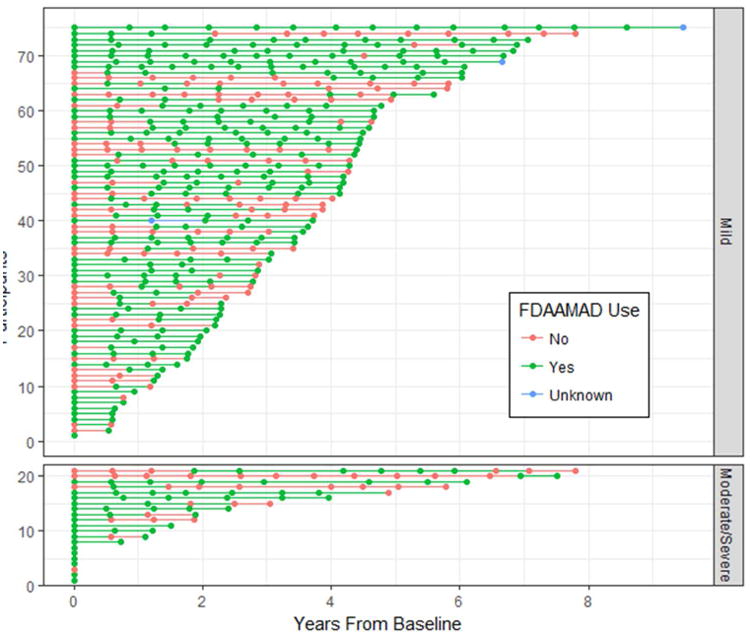

Of the total sample, 97 (35%) ever used FDAAMAD at any time over the course of the study. Fifty-five participants were on one or more of these medications at baseline and 42 started later. Figure 2 displays the pattern and duration of FDAAMAD use for those who ever used the medication(s), stratified by baseline level of dementia severity (Mild vs. Moderate/Severe on the Global CDR). Psychotropic medication use was common in the overall sample with 68.6% of participants ever using the medication, while use of medications with anticholinergic properties was less common with 37.5% of participants ever using medications with anticholinergic effects. Recognizing that some psychotropic drug classes have anticholinergic effects, in our sample, those with anticholinergic properties were 13.4% for SSRI's; 5.1% for antipsychotics; 2.9% for tricyclic antidepressants; 2.9% for anxiolytics; 2.9% for benzodiazepines; 0.7% for sedatives/hypnotics; 0.4% for bupropion; and 0.4% for mood stabilizers.

Figure 2. Participant Pattern of Antidementia Medication Use Over Time.

Association of FDAAMAD and Informal Costs

All participants

With the inclusion of significant covariates, use of FDAAMAD was not associated with informal costs (expβ = .73, p = .060). Of the covariates, only dementia severity (CDR-SB), was significantly associated with costs such that with each unit increase in CDR-SB, there was an 16% increase in informal costs (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of Informal Costs of Dementia Care and Antidementia Medication in Utah 2015 Cost Value.

| Parameter | Model with entire sample (N = 280) | Model with baseline mild severity (N = 222) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Exp(β) | p | 95% confidence lower upper | Exp(β) | p | 95% confidence lower upper | |||

| Intercept | 16.03 | < .001 | 10.78 | 23.83 | 14.50 | < .001 | 8.98 | 23.43 |

| Time (years) | .99 | .763 | .89 | 1.09 | .98 | .794 | .87 | 1.11 |

| Taking antidementia meds | .73 | .060 | .53 | 1.01 | .68 | .038 | .48 | .98 |

| CDR-SB | 1.16 | <.001 | 1.12 | 1.19 | 1.18 | <.001 | 1.12 | 1.25 |

Table 2 displays GEE model results of factors predicting informal care costs for the overall sample and for the subsample of persons with mild dementia at baseline.

Note all tests of parameter significance had df = 1.

Restricted Participants (CDR = 0.5 or 1.0)

When restricting the sample to only include those participants with mild dementia at baseline (N = 222), use of FDAAMAD was associated with a 32% reduction in informal costs (expβ = .68, p = .038). Again, dementia severity was associated with informal costs such that with each unit increase in CDR-SB there was an 18% increase in informal costs.

Discussion

In this examination of the informal costs of dementia care in a population-based sample, we found no significant associations with the use of FDAAMAD overall. However, when restricting the sample to only those with mild dementia at baseline, use of FDAAMAD was associated with a 32% reduction in informal costs. Our results are similar to the literature that links these medications to lower total costs in both mild and moderate AD (Fillit and Hill, 2005) where savings over two-years ranged from $73 to over $2,000. Similarly, use of FDAAMAD was associated with lower medical costs (Lu et al., 2005).

The current results add to our earlier findings of factors that affect informal costs. Previously, we reported that closer caregiver-care recipient relationships are associated with 24% lower costs of informal care (Rattinger et al., 2016). This raises the possibility that interventions which reduce the rate of decline in dementia may not only enhance overall patient well-being but also reduce informal costs. Although not examined here, other potential benefits may include caregiver outcomes of reduced burden and caregiver psychiatric and medical morbidity, which may influence formal costs of care as incurred with patient institutionalization.

The number of participants in our sample that ever used FDAAMAD (35% of the overall sample) was relatively small. This may have resulted in less power to detect a significant association overall. The frequency of FDAAMAD use reported in the DPS at baseline (22.6%) was similar in rates reported in other representative samples at the time of the study. For example, Gruber-Baldini et al. (2007) evaluated a nationally representative sample of 12,697 persons with dementia from a Medicare database in 2002, also the starting year of DPS. Findings were that 24.7% of individuals reported using ChEIs: donepezil, galantamine, or rivastigmine (Gruber-Baldini et al., 2007). A more recent cross-sectional study reported that 57.1% of Medicare beneficiaries with dementia were on FDAAMAD (Rattinger et al., 2013), suggesting an increase in rates of such medication use since the time of DPS. However, no information was provided on longitudinal pattern or duration of use. Our data suggest that at least in the Cache County cohort, those who initiate FDAAMAD generally maintain usage over time.

As expected, and consistent with other work, greater severity of dementia was associated with higher informal costs. Zhu et al. (2006a) reported that greater disease severity corresponded to an increase in the use of informal care. In previous work in the DPS cohort, informal costs increased with dementia severity, approximately 18% per year after dementia onset and 5% to 8% per year when holding baseline severity constant (Rattinger et al., 2015).

The strengths of the study include the population-based cohort of the DPS, the longitudinal study design, and high participation rates (85% initial enrollment and 95-100% follow-up excluding nonparticipation due to death). Limitations include the heterogeneous forms of dementia represented in the sample and the inability to examine use of specific FDAAMAD – the small sample size did not permit an analysis of the effects of individual medications by dementia type. The homogeneous population of Cache County, predominantly Caucasian and majority members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, may limit generalizability of results. Finally, the DPS as an observational study without random assignment to medication condition, cannot establish that use of FDAAMAD reduces the informal costs of dementia care.

In summary, we report lower informal costs of dementia care associated with the use of FDAAMAD among persons of mild dementia severity. In future studies, it may be useful to examine the effects of other modifiable factors that affect dementia progression with respect to the informal costs of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the DPS participants and their caregivers for their generous time commitment and information provided to the study. The authors would also like to thank the original Cache County Study and DPS investigators.

Footnotes

Presented in preliminary form at the 21st International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics World Congress of Gerontology and Geriatrics, San Francisco, CA

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- Alzheimer's Association. 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, D.C: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Atri A. Effective pharmacological management of Alzheimer's disease. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2011;17:S346–S355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitner JCS, et al. APOE-E4 count predicts age when prevalence of AD increases, then declines. Neurology. 1999;53:321–331. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Consumer Price Index 2016a [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Occupational Employment Statistics 2016b [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, et al. Reliability of the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:31–32. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520250037015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N, Boustani M. In: Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale. A. B. P. o. t. I. U. C. f. A. Research, editor. The Wishard: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carriere I, et al. Drugs with anticholinergic properties, cognitive decline, and dementia in an elderly general population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:1317–1324. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, et al. The Caregiver Activity Survey (CAS): development and validation of a new measure for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;12:978–988. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199710)12:10<978::aid-gps659>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooneief G, Marder K, Tang MX, Stern Y. The Clinical Dementia Rating scale: community-based validation of “profound’ and “terminal’ stages. Neurology. 1996;46:1746–1749. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkinjuntti T, Kurz A, Gauthier S, Bullock R, Lillienfeld S, ChandrasekharRao VD. Efficacy of galantamine in probable vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease combined with cerebrovascular disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillit H, Hill J. Economics of dementia and pharmacoeconomics. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2005;3:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber-Baldini AL, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, Simoni-Wastila L, Miller R. Treatment of dementia in community-dwelling and institutionalized medicare beneficiaries. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2007;55:1508–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danzinger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;55:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd M, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen K, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa KM, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:770–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Hill J, Fillit H. Impact of Donepezil Use in Routine Clinical Practice on Health Care Costs in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias Enrolled in a Large Medicare Managed Care Plan: A Case-Control Study. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy (AJGP) 2005;3:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoutsakos JM, et al. Effects of general medical health on Alzheimer's progression: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1561–70. doi: 10.1017/S104161021200049X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, et al. Population-based study of medical comorbidity in early dementia and ‘Cognitive Impairment No Dementia (CIND)’: Association with functional and cognitive impairment: The Cache County Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:656–664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein MF, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan E. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke MM, et al. Effects of Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for Alzheimer's disease on clinical progression. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton MC, et al. Caregiver-recipient closeness and symptom progression in Alzheimer disease. The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:560–568. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bryant SE, et al. Validation of the New Interpretive Guidelines for the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes Score in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Database. Archives of Neurology. 2010;67:746–749. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod JD, Kane RL, Finch MD, Kane RA. Effects of post hospital Medicare home health and informal care on patient functional status. Health Services Research. 1998;33:513–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattinger GB, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic management of dementia across settings of care. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2013;61:723–733. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattinger GB, et al. Closer caregiver and care-recipient relationships predict lower informal costs of dementia care: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2016;12:917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattinger GB, et al. Dementia severity and the longitudinal costs of informal care in the Cache County population. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2015;11:946–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree SD, Atri A, Lopez OL, Doody RS. Effectiveness of antidementia drugs in delaying Alzheimer's disease progression. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore-Roth L. 2009 Mosby's Nursing Drug Reference. Mosby Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tschanz JT, et al. Progression of cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric symptoms in a population cohort with Alzheimer dementia: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19:532–542. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181faec23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschanz JT, et al. Caregiver coping strategies predict cognitive and functional decline in dementia: the Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi P. Do statins reduce risk of incident dementia and Alzheimer disease?: The Cache County Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CW, et al. Clinical characteristics and longitudinal changes of informal costs of Alzheimer's disease in the community. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 2006a;54:1596–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CW, et al. Longitudinal study of effects of patient characteristics on direct costs in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006b;67:998–1005. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000230160.13272.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]