Abstract

Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) increases basal sympathetic nervous system activity, augments chemoreflex-induced sympathoexcitation, and raises blood pressure. All effects are attenuated by systemic or intracerebroventricular administration of angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) antagonists. This study aimed to quantify the effects of CIH on AT1R- and AT2R-like immunoreactivity in the rostroventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), central regions that are important components of the extended chemoreflex pathway. Eighteen Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed to intermittent hypoxia (FIO2 = 0.10, 1 min at 4-min intervals) for 10 hr/day for 1, 5, 10, or 21 days. After exposure, rats were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were removed and sectioned coronally into 50 µm slices. Immunohistochemistry was used to quantify AT1R and AT2R in the RVLM and the PVN. In the RVLM, CIH significantly increased the AT1R-like immunoreactivity, but did not alter AT2R immunoreactivity, thereby augmenting the AT1R:AT2R ratio in this nucleus. In the PVN, CIH had no effect on immunoreactivity of either receptor subtype. The current findings provide mechanistic insight into increased basal sympathetic outflow, enhanced chemoreflex sensitivity, and blood pressure elevation observed in rodents exposed to CIH.

Keywords: Immunohistochemistry, rostroventrolateral medulla, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, chemoreflex, sympathetic nervous system, blood pressure, rats

Introduction

Rats exposed to intermittent hypoxia for 7–12 hours per day (CIH) demonstrate blood pressure elevations that are evident, not only during the exposure periods, but also during portions of the day when they are unperturbed (1–3). This hypertensive effect was greatly attenuated by systemic administration of losartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) antagonist (2–4); however, these early studies did not provide information regarding the specific site(s) of action of the drug. More recently, multiple lines of evidence indicate that angiotensin II receptors within the central nervous system play important mechanistic roles in CIH-induced hypertension. These include attenuation of CIH-induced hypertension with central administration of Ang II receptor antagonists (5) and by adenoviral knockdown of angiotensin converting enzyme-1 (6) and AT1R (7). Our laboratory has demonstrated that CIH sensitizes chemoreflex control of sympathetic vasoconstrictor outflow, an effect that is dependent on signaling through AT1R and associated with increased expression of AT1R in the carotid body (8). Accordingly, the purpose of the present study was to quantify AT1R- and AT2R-like immunoreactivity in the rostral ventrolateral medulla and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, two central components of the extended chemoreflex pathway that substantially influence tonic and reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity (9–11).

Materials and methods

Animals

Eighteen adult male Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed to CIH or normoxia (see below) for 1, 5, 10, or 21 days. Age and body weight data are shown in Table 1. Ad libitum access was provided to drinking water and standard chow (Harlan Teklad #8604). Experiments were carried out in accordance with recommendations set forth in the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication #8023, revised 1978). The protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Ventilatory, cardiovascular, and metabolic responses to CIH or normoxia were reported previously (12,13).

Table 1.

Rat ages and weights at the time of tissue harvest following exposure to normoxia or chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH). Data shown are means±SE. Unpaired t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences in age (p = 0.22) or weight (p = 0.79) between the normoxia and combined 5, 10, and 21-day CIH groups.

| Normoxia (n = 6) |

CIH 1-day (n = 2) |

CIH 5-day (n = 2) |

CIH10-day (n = 4) |

CIH 21-day (n = 4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (wk) | 17.3 ± 0.8 | 17.0 ± 0.0 | 16.4 ± 0.0 | 16.1 ± 0.3 | 17.9 ± 0.5 |

| Body mass (g) | 412 ± 5 | 418 ± 2 | 413 ± 11 | 409 ± 5 | 416 ± 5 |

CIH and normoxia (NORM) exposures

Rats, in their home cages, were placed into a Plexiglas chamber and exposed to intermittent hypoxia for 10 hr/day (0600–1600 hr). The fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) was reduced to 0.10 for 1 min at 4-min intervals. Thus, our CIH paradigm produced a saturation profile that mimics moderately severe obstructive sleep apnea in humans (15 events/hr, nadir SpO2, 75%). Control rats were housed under normoxic conditions adjacent to the hypoxia chamber where they were exposed to light, noise, and temperature stimuli similar to those experienced by the CIH rats. Otherwise, all CIH- and normoxia-exposed rats were handled in identical fashion. To examine potential effects of CIH on carotid body glomus cell proliferation, bromodeoxyuridine (0.8 mg/ml) was added to the drinking water starting 12 hr prior to, and continuing throughout, all exposures. Carotid bifurcations, including the carotid bodies and superior cervical ganglia, were removed immediately prior to brain harvest. Before and after CIH or NORM, and at weekly intervals during the 21-day exposures, all rats underwent assessments of ventilatory and metabolic responses to acute, graded hypoxia in a full-body plethysmograph, the final tests occurring at least 2 hr prior to harvesting of brain tissue. For details of CIH and normoxic exposures and plethysmograph tests, please see Morgan et al. (13). The results of carotid body immunohistochemical analyses and plethysmograph tests have been reported previously (13).

Quantification of central nervous system angiotensin II receptors

At the end of the CIH or NORM exposures, rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to clear the red cells, followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (300–500 ml, 25 ml/minute). Brains were then removed, stored in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and then transferred to PBS until sectioned.

Brains were sectioned coronally into 50 µm slices with a vibratome using standard stereotaxic coordinates (14). All sections were washed in PBS (pH 7.5), incubated for 30 min in a 1% solution of sodium borohydride and PBS at room temperature, and blocked in ICC blocking buffer (PBS with 0.25% gelatin, 2% normal goat serum, 0.03% triton-x 100, 0.1% thimerosal, and 0.05% neomycin) for 1.5 hr, shaking, at room temperature.

Antibodies were created according to Premer et al., 2013 (15). Antibodies were diluted in the aforementioned blocking solution with 0.05% sodium azide at the following concentrations: AT1R, 1:1600 and AT2R, 1:5000. Negative control sections were incubated in blocking solution. The diluted antibody or blocking solution was incubated with the brain sections for 17 hr at 4° C, while shaking. After exposure to primary antibody, sections were repeatedly washed in blocking buffer. Secondary antibody (Cy3 Fab goat anti rabbit IgG H + L [Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA]) was diluted 1:600 in PBS and incubated with all tissues 1 hr, shaking, at room temperature. Tissues were then washed overnight at 4° C. in PBS with several changes to reduce nonspecific binding.

The brain slices were mounted on poly-L-lysine slides and coverslipped with SlowFade Diamond Mounting Media (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Images were acquired using an epifluorescence microscope with UV illumination (Eclipse E600, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), a Nikon DS-Fi1c digital camera, and a Plan Apochromat 10×/0.45 numerical aperture objective. The capture parameters were set at an exposure of 1000 msec and a gain of 1.4. For the RVLM, we identified a coronal section that lacked dorsal cochlear nucleus but contained an external cuneate nucleus bulge and a deep raphe pallidus nucleus cleft (−12.0 to −12.5 mm from Bregma). The RVLM was located as an area ventral or ventromedial to the ambiguus nucleus (2.0 to 2.3 mm from midline). In a coronal section caudal to the point of anterior commissure shortening, the PVN was located adjacent the third ventricle (−1 to −2 mm from Bregma; 0.2 to 0.5 mm from midline). Tissue fluorescence was quantified using NIS-elements D software. Mean intensity of fluorescence was calculated by creation of a region of interest around or inside the RVLM or PVN approximately 82000 pixels in area for each picture. Background fluorescence was calculated by random selection of a brain area outside of the regions of interest approximately 3000 pixels in area.

Data analysis

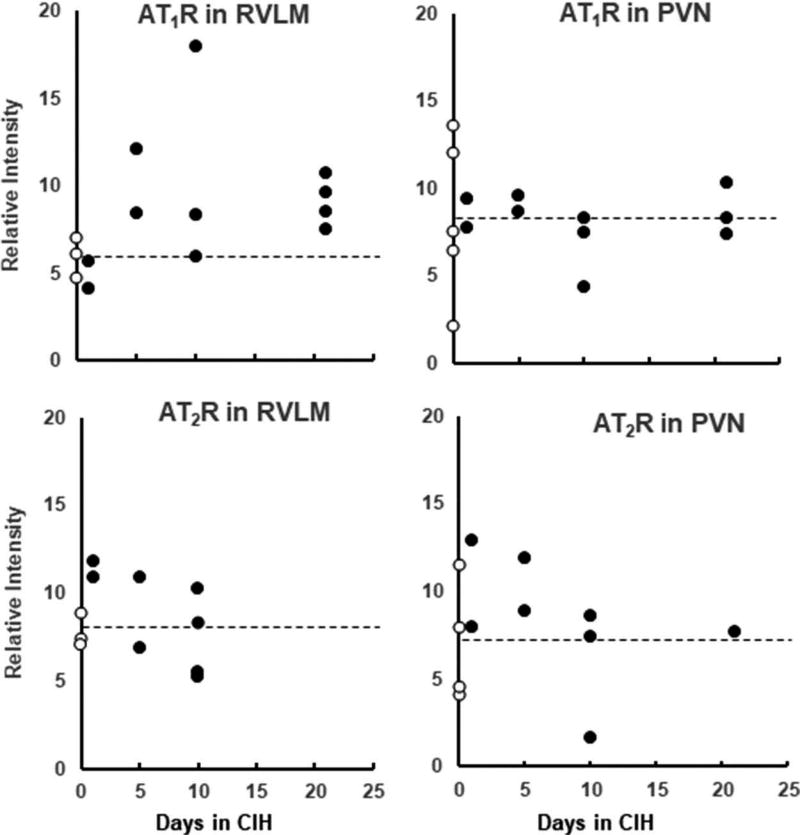

Relative intensity (object intensity minus background intensity) was calculated for the stained receptors in each acceptable image. Relative intensities from images of the same receptor type/region/CIH duration (4.8 ± 0.4 images/rat) were averaged. Data from individual rats for the 2 receptor subtypes in the 2 nuclei are shown in Figure 1. Because there were no apparent differences among rats with 5, 10, and 21-day exposures, we combined these groups to best represent the effect of CIH. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare data from normoxic control rats with combined data from 5-, 10-, and 21-day CIH-exposed rats. In animals where both AT1R and AT2R quantifications were available (RVLM, n = 10; PVN, n = 11), AT1R:AT2R ratio was calculated.

Figure 1.

Mean values for immunoreactivity in the two Ang II receptor subtypes in the 2 nuclei for individual rats in the normoxia group (0 days of chronic intermittent hypoxia [CIH]; open circles) and in rats exposed to CIH (closed circles) for 1, 5, 10, and 21 days. The dashed line shows the mean relative intensity for the normoxia group.

Results

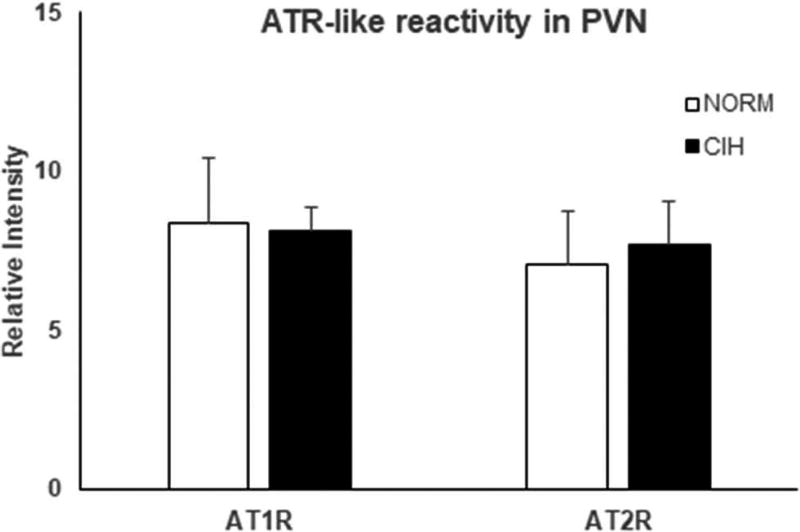

Effects of CIH on ATR-like immunoreactivity in PVN (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

AT1R- and AT2R-like immunoreactivity in the PVN in combined 5, 10, and 21-d chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH)-exposed and normoxic control (NORM) rats. CIH did not alter the immunoreactivity of either receptor subtype in this nucleus. Means±SE. *p < 0.05

CIH did not affect AT2R immunoreactivity in PVN (p = 0.78). Likewise, AT1R immunoreactivity in this region was unaffected by CIH (p = 0.93). Figure 3 shows representative PVN images for the two receptor subtypes in CIH vs. NORM rats.

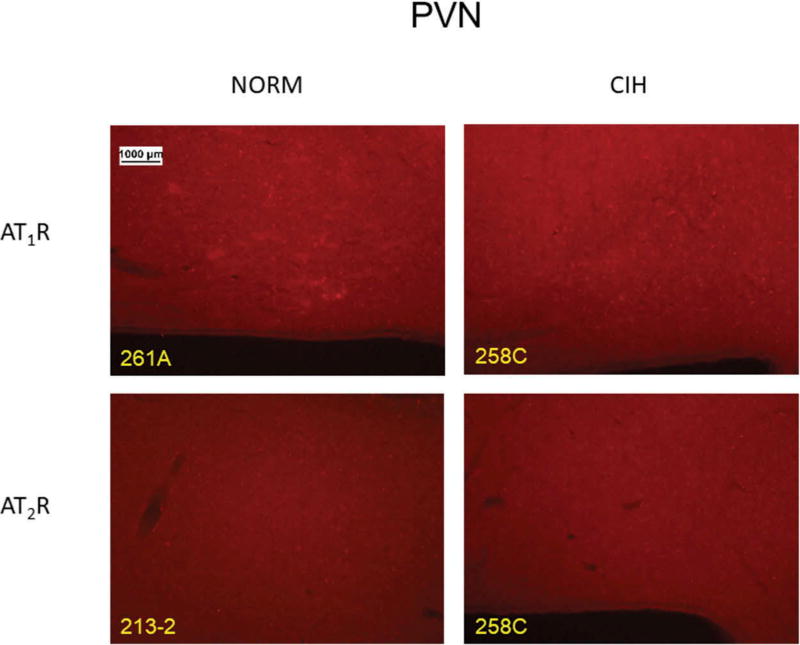

Figure 3.

Representative images for each receptor subtype in the PVN in normoxic control (NORM) and chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH)-exposed rats.

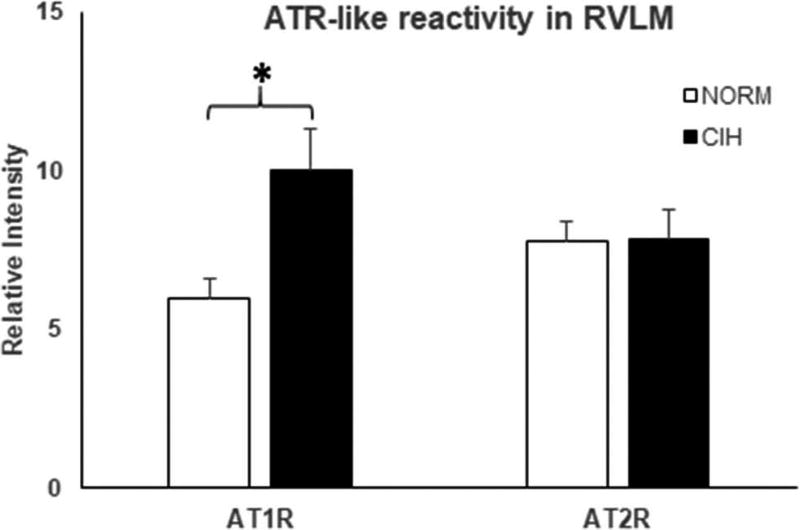

Effects of CIH on ATR-like immunoreactivity in RVLM (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

AT1R- and AT2R-like immunoreactivity in the RVLM in combined 5, 10, and 21-day chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH)-exposed and normoxic control (NORM) rats. CIH exposure increased AT1R-reactivity in the RVLM. In contrast, CIH had no effect on AT2R-like immunoreactivity in the RVLM. Means±SE. *p < 0.05.

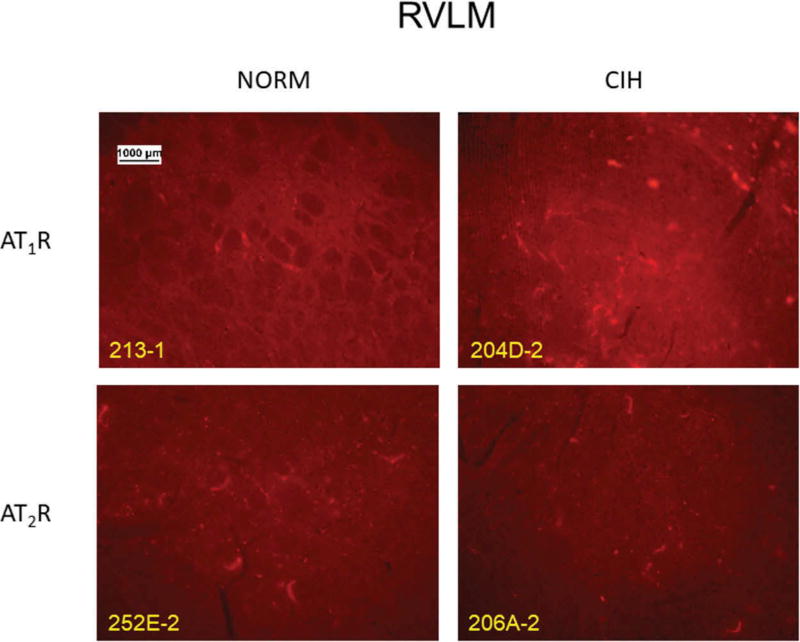

CIH failed to alter AT2R immunoreactivity in RVLM (p = 0.99). In contrast, CIH lasting at least 5 days significantly increased the AT1R-like reactivity in this nucleus (p = 0.02). Anecdotally, in a sample of 2 rats, we saw no change in immunoreactivity after 1 day of CIH exposure. Figure 5 shows representative RVLM images for the two receptor subtypes in CIH vs. NORM rats.

Figure 5.

Representative images for each receptor subtype in the RVLM in normoxic control (NORM) and chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH)-exposed rats.

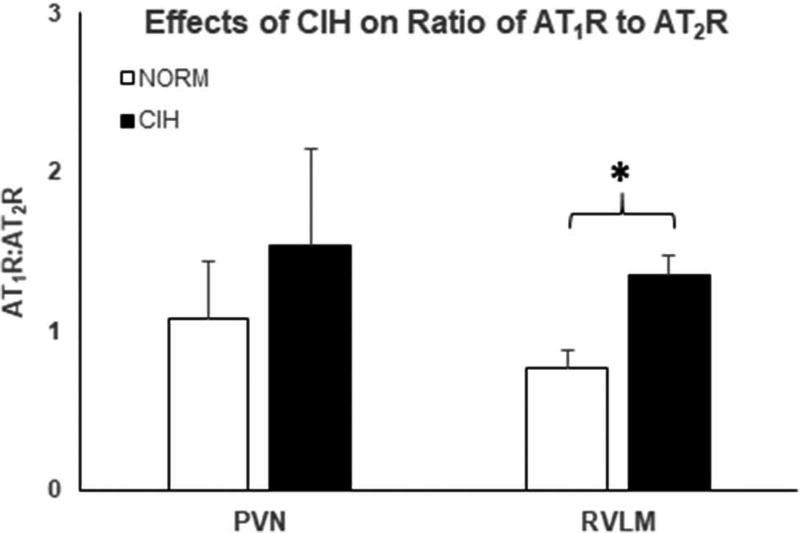

Effects of CIH on the AT1R to AT2R ratio (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Ratios of the relative intensities of AT1R and AT2R like immunoreactivity in the PVN (left) and the RVLM (right). Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) exposure did not significantly alter this ratio in the PVN, whereas CIH exposure increased AT1R:AT2R ratio in the RVLM. Means±SE. *p < 0.05.

In PVN, the ratio of the receptor subtypes was unaffected by CIH (p = 0.54). In contrast, CIH augmented the AT1R:AT2R ratio in RVLM (p = 0.02), arising from an elevation in AT1R without a concomitant reduction in AT2R.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that exposure to CIH of at least 5 days duration augmented AT1R-like immunoreactivity in RVLM. In contrast, CIH exposure did not affect AT2R-like reactivity in RVLM or that of either Ang II receptor subtype in PVN. These findings provide insight into the mechanisms of sympathetic nervous system overactivity and hypertension produced by CIH in rodents, an intervention commonly used to model human sleep apnea.

Role of central AT1R in blood pressure regulation

The AT1R in RVLM appears to be a key determinant of blood pressure in animal models of hypertension, as first suggested by studies of the pressor effects of Ang II administered into the RVLM of the cat (16,17). As reviewed by Bourassa et al. (9), administration of an AT1R antagonist directly into the RVLM of a normotensive rat on a normal salt diet that is water replete has minimal effect on blood pressure. However, in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (18,19), the TGR (mREN2)2 hypertensive rat (20), Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats (21), and Sprague-Dawley rats consuming a high salt diet (22), administration of an AT1R antagonist into the RVLM has a profound depressor effect. Moreover, in SHR (18,23), Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats (21), and Sprague-Dawley rats consuming a high salt diet (22), administration of Ang II into the RVLM has a greater pressor effect than is seen in normotensive rats. Interestingly, Dahl salt-resistant, normotensive rats on a low salt diet (21) and water-deprived Sprague-Dawley rats (24) showed a reduction in blood pressure when an AT1R antagonist was injected into the RVLM. This suggests that under conditions of hyponatremia or hypovolemia, which activates the circulating reninangiotensin system, there is also an up-regulation of AT1R stimulation in the RVLM (21). Consistent with the concept of an up-regulation of AT1R in the RVLM with hypertension, we previously observed an increase in AT1R binding in the RVLM of the SHR (25). The present finding of an increase in AT1R-like immunoreactivity in the RVLM produced by CIH expands the sphere of up-regulation of RVLM AT1R as a mechanism of hypertension (see review (26)) to include CIH-induced hypertension.

Central AT1R influence on sympathetic nervous system activity

Central Ang II receptors, more specifically the relative expression of AT1R and AT2R in the RVLM, play pivotal roles in establishing the tonic level of sympathetic outflow (9,26–29). Intracerebroventricular and systemic infusions of Ang II increase the abundance of AT1R in RVLM, augment sympathetic nerve traffic and raise blood pressure (27,30). Recent evidence indicates that Ang II receptor binding alters neuronal activity in nuclei involved in cardiovascular control via pathways that generate superoxide ion (31–33) and downregulate nNOS (34).

In addition to their role in determining basal sympathetic tone, Ang II receptors contribute importantly to the sympathetic activation elicited by acute hypoxia. Chemoreflex-stimulated sympathoexcitation is dependent, at least in part, on AT1R signaling in carotid body and also in the nucleus of the solitary tract, RVLM, and PVN, other essential components of the extended chemoreflex arc (11,31,35,36).

In rodent models of sleep apnea, intermittent hypoxia applied for several hours per day evokes increases in basal sympathetic outflow, sympathetic and ventilatory responsiveness to chemoreceptor stimulation, and blood pressure that are evident not only during exposures but also during the intervening normoxic periods (8,13,37,38). Several lines of evidence indicate that central AT1R and AT2R play important roles in producing these “carryover” effects. First, CIH-induced hypertension can be attenuated by intracerebroventricular administration of the AT1R antagonist losartan, an intervention that also reduced expression of FosB/ΔFosB in the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, subfornical organ, median preoptic nucleus, nucleus of the solitary tract, RVLM, and dorsal and medial parvocellular subnuclei of the PVN (5). In addition, viral-mediated delivery of short hairpin RNA to knockdown angiotensin converting enzyme-1 in the median pre-optic nucleus of the hypothalamus (6) and AT1R in the subfornical organ (7) greatly attenuates the hypertensive response to CIH. Finally, systemic administration of losartan prevented CIH-induced increases in basal sympathetic nerve activity, chemoreflex-induced sympathoexcitation and hyperventilation, and blood pressure (3,8,38).

Pathophysiologic causes of AT1R proliferation

Under physiologic conditions, variations in activation of central nervous system AT1R are essential for maintenance of salt and water homeostasis (39–44). Pathophysiologic upregulation of the AT1R has been observed: 1) in the carotid body of rats exposed to chronic continuous hypoxia (45); 2) in the carotid body and RVLM of animals with experimental, pacing-induced heart failure (28,46); and 3) in the RVLM and PVN of rats with renovascular hypertension (47). In addition, intracerebroventricular and systemic infusions of Ang II increase the abundance of AT1R in the RVLM, augment sympathetic nerve traffic, and raise blood pressure (27,30,48). The present data suggest that CIH-induced upregulation of RVLM AT1R and an increase in the AT1R:AT2R ratio, along with upregulation of AT1R in carotid body (8,49), are responsible for sustained sympathetic activation, hyperventilation in normoxia (13,38) and diurnal blood pressure elevations in this animal model.

Limitations/experimental considerations

Because immunohistochemistry is a semi-quantitative technique, the present findings require confirmation by mRNA and protein measurements, radioligand binding assays and functional responses to Ang II and AT1R antagonist administration into the RVLM. Nevertheless, we would like to emphasize that the current findings are consistent with previous findings from our laboratory, obtained by Western blot analysis, of increased AT1R expression in the carotid body (8) and increased AT1R:AT2R ratio in saphenous artery (3).

In conclusion, we found that CIH exposure increased AT1R-like immunoreactivity and AT1R:AT2R ratio in the RVLM, but had no effect on these variables in PVN. The current findings provide mechanistic insight into the increased basal sympathetic outflow (8), enhanced chemoreflex sensitivity (8,13,38,50,51), and blood pressure elevation (1–3,37,52) observed in rodents exposed to CIH. The present findings may also explain, at least in part, the sympathetic overactivity (53), enhanced chemoreflex responsiveness (54,55) and hypertension (56) observed in humans with sleep apnea and provide rationale for pharmacotherapy in this common condition.

Acknowledgments

The skillful technical assistance of Mr. Russell Adrian is gratefully acknowledged. This research was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (UO-1 105365; J.M. Dopp, PI).

Footnotes

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/iceh.

Declaration of Interest

R.C. Speth has licensed the antibody development technology for commercial sale to Advanced Targeting Systems, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA (92121). The immunochemical studies conducted by M. Brownfield did not benefit ImmunoStar (i.e. they do not offer these antibodies).

References

- 1.Fletcher EC, Lesske J, Qian W, Mille CC, Unger T. Repetitive, episodic hypoxia causes diurnal elevation of blood pressure in rats. Hypertension. 1992;19:555–61. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinojosa-Laborde C, Mifflin SW. Sex differences in blood pressure response to intermittent hypoxia in rats. Hypertension. 2005;46:1016–21. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175477.33816.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus NJ, Philippi NR, Bird CE, Li YL, Schultz HD, Morgan BJ. Effect of AT1 receptor blockade on intermittent hypoxia-induced endothelial dysfunction. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;183:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher EC, Bao G, Li R. Renin activity and blood pressure in response to chronic episodic hypoxia. Hypertension. 1999;34:309–14. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight WD, Saxena A, Shell B, Nedungadi TP, Mifflin SW, Cunningham JT. Central losartan attenuates increases in arterial pressure and expression of FosB/ΔFosB along the autonomic axis associated with chronic intermittent hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R1051–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00541.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulk KE, Nedungadi TP, Cunningham JT. Angiotensin converting enzyme 1 in the median preoptic nucleus contributes to chronic intermittent hypoxia hypertension. Physiol Rep. 2017;5(10):e13277. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxena A, Little JT, Nedungadi TP, Cunningham JT. Angiotensin II type 1a receptors in subfornical organ contribute towards chronic intermittent hypoxia-associated sustained increase in mean arterial pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H435–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00747.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcus NJ, Li YL, Bird CE, Schultz HD, Morgan BJ. Chronic intermittent hypoxia augments chemoreflex control of sympathetic activity: role of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;171:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourassa EA, Sved AF, Speth RC. Angiotensin modulation of rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) in cardiovascular regulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dampney RA, Horiuchi J, Tagawa T, Fontes MA, Potts PD, Polson JW. Medullary and supramedullary mechanisms regulating sympathetic vasomotor tone. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:209–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy MK, Patel KP, Schultz HD. Differential role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in modulating the sympathoexcitatory component of peripheral and central chemoreflexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R789–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00222.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan BJ, Adrian R, Bates ML, Dopp JM, Dempsey JA. Quantifying hypoxia-induced chemoreceptor sensitivity in the awake rodent. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2014(117):816–24. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00484.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan BJ, Adrian R, Wang ZY, Bates ML, Dopp JM. Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters ventilatory and metabolic responses to acute hypoxia in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2016 May 15;120(10):1186–1195. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00015.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paxinos G, Watson C, Carrive P, Kirkcaldie M, Ashwell KWS. Chemoarchitectonic Atlas of the rat brain. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Premer C, Lamondin C, Mitzey A, Speth RC, Brownfield MS. Immunohistochemical localization of AT1a, AT1b, and AT2 angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the rat adrenal, pituitary, and brain with a perspective commentary. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013:175428. doi: 10.1155/2013/175428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen AM, Dampney RA, Mendelsohn FA. Angiotensin receptor binding and pressor effects in cat subretrofacial nucleus. Am.J.Physiol. 1988;255:H1011–H1017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.5.H1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreatta SH, Averill DB, Santos RA, Ferrario CM. The ventrolateral medulla. New Site Action Renin-Angiotensin Syst Hypertension. 1988;11:I163–I166. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.2_pt_2.i163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito S, Komatsu K, Tsukamoto K, Kanmatsuse K, Sved AF. Ventrolateral medulla AT1 receptors support blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2002;40:552–59. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000033812.99089.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen AM. Blockade of angiotensin AT1-receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of spontaneously hypertensive rats reduces blood pressure and sympathetic nerve discharge. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2001;2:S120–S124. doi: 10.1177/14703203010020012101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fontes MA, Baltatu O, Caligiorne SM, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Ganten D, Bader M, Santos RA. Angiotensin peptides acting at rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to hypertension of TGR (mREN2)27 rats. Physiol Genomics. 2000;2:137–42. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.2.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito S, Hiratsuka M, Komatsu K, Tsukamoto K, Kanmatsuse K, Sved AF. Ventrolateral medulla AT1 receptors support arterial pressure in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2003;41:744–50. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052944.54349.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams JM, McCarthy JJ, Stocker SD. Excess dietary salt alters angiotensinergic regulation of neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Hypertension. 2008;52:932–37. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.118935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muratani H, Averill DB, Ferrario CM. Effect of angiotensin II in ventrolateral medulla of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R977–R984. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.5.R977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman KL, Brooks VL. AT(1) and glutamatergic receptors in paraventricular nucleus support blood pressure during water deprivation. Am.J Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1675–R1682. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00623.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourassa EA, Fang X, Li X, Sved AF, Speth RC. AT angiotensin II receptor and novel non-AT, non-AT angiotensin II/III binding site in brainstem cardiovascular regulatory centers of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Brain Research. 2010;1359:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dampney RA, Tan PS, Sheriff MJ, Fontes MA, Horiuchi J. Cardiovascular effects of angiotensin II in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: the push-pull hypothesis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2007;9:222–27. doi: 10.1007/s11906-007-0040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Sympathoexcitation by central ANG II: roles for AT1 receptor upregulation and NAD(P)H oxidase in RVLM. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2271–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00949.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao L, Wang WZ, Wang W, Zucker IH. Imbalance of angiotensin type 1 receptor and angiotensin II type 2 receptor in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: potential mechanism for sympathetic overactivity in heart failure. Hypertension. 2008;52:708–14. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao L, Zucker IH. AT2 receptor signaling and sympathetic regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braga VA. Differential brain angiotensin-II type I receptor expression in hypertensive rats. J Vet Sci. 2011;12:291–93. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2011.12.3.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braga VA, Colombari E, Jovita MG. Angiotensin II-derived reactive oxygen species underpinning the processing of the cardiovascular reflexes in the medulla oblongata. Neurosci Bull. 2011;27:269–74. doi: 10.1007/s12264-011-1529-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Lang JA, Sinnayah P, Ahmad IM, Spitz DR, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates the actions of angiotensin II in the central nervous system. Circ Res. 2002;91:1038–45. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043501.47934.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Case AJ, Li S, Basu U, Tian J, Zimmerman MC. Mitochondriallocalized NADPH oxidase 4 is a source of superoxide in angiotensin II-stimulated neurons. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H19–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00974.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campese VM, Ye S, Zhong H. Downregulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase and interleukin-1beta mediates angiotensin II-dependent stimulation of sympathetic nerve activity. Hypertension. 2002;39:519–24. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.102815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung ML. Expressions of angiotensin and cytokine receptors in the paracrine signaling of the carotid body in hypoxia and sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;209:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stern JE, Son S, Biancardi VC, Zheng H, Sharma N, Patel KP. Astrocytes contribute to angiotensin II stimulation of hypothalamic neuronal and sympathetic outflow. Hypertension. 2016;68:1483–93. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcus NJ, Olson EB, Bird CE, Philippi NR, Morgan BJ. Time-dependent adaptation in the hemodynamic response to hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;165:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan BJ, Bates ML, Rio RD, Wang Z, Dopp JM. Oxidative stress augments chemoreflex sensitivity in rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2016;234:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fitzsimons JT. Angiotensin, thirst, and sodium appetite. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:583–686. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rl T, Ak J. Effects of hypotension and fluid depletion on central angiotensin-induced thirst and salt appetite. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1726–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.5.R1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazartigues E, Sinnayah P, Augoyard G, Gharib C, Johson AK, Davisson RL. Enhanced water and salt intake in transgenic mice with brain-restricted overexpression of angiotensin (AT1) receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1539–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00751.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss ML, Moe KE, Epstein AN. Interference with central actions of angiotensin II suppresses sodium appetite. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:R250–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.2.R250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charron G, Laforest S, Gagnon C, Drolet G, Mouginot D. Acute sodium deficit triggers plasticity of the brain angiotensin type 1 receptors. Faseb J. 2002;16:610–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0531fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII Angiotensin II Receptors Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung PS, Lam SY, Fung ML. Chronic hypoxia upregulates the expression and function of AT(1) receptor in rat carotid body. J Endocrinol. 2000;167:517–24. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1670517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultz HD. Angiotensin and carotid body chemoreception in heart failure. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:144–49. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campos RR, Oliveira-Sales EB, Nishi EE, Paton JF, Bergamaschi CT. Mechanisms of renal sympathetic activation in renovascular hypertension. Exp Physiol. 2015;100:496–501. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.079855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nunes FC, Braga VA. Chronic angiotensin II infusion modulates angiotensin II type I receptor expression in the subfornical organ and the rostral ventrolateral medulla in hypertensive rats. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2011;12:440–45. doi: 10.1177/1470320310394891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lam SY, Liu Y, Ng KM, Liong EC, Tipoe GL, Leung PS, Fung ML. Upregulation of a local renin-angiotensin system in the rat carotid body during chronic intermittent hypoxia. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:220–31. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.074591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng Y, Kline DD, Dick TE, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia enhances carotid body chemoreceptor response to low oxygen. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;499:33–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1375-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Del Rio R, Moya EA, Iturriaga R. Carotid body potentiation during chronic intermittent hypoxia: implication for hypertension. Front Physiol. 2014;5:434. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Troncoso Brindeiro CM, Da Silva AQ, Allahdadi KJ, Youngblood V, Kanagy NL. Reactive oxygen species contribute to sleep apnea-induced hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2971–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00219.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carlson JT, Hedner J, Elam M, Ejnell H, Sellgren J, Wallin BG. Augmented resting sympathetic activity in awake patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1993;103:1763–68. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Pesek CA, Dyken ME, Montano N, Somers VK. Selective potentiation of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 1999;99:1183–89. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansukhani MP, Wang S, Somers VK. Chemoreflex physiology and implications for sleep apnoea: insights from studies in humans. Exp Physiol. 2015;100:130–35. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.082826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Becker HF, Jerrentrup A, Ploch T, Grote L, Penzel T, Sullivan CE, Peter JH. Effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2003;107:68–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042706.47107.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]