Abstract

Objective

The main aim of the study was to assess physicians’ utilization of microbiologic reports and determinants of their preference in ordering microbiologic culture among patients with systemic bacterial infection at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital.

Results

Of the total 369 patients observed, 91 (24.7%) had microbiologic reports (culture and gram stain). About 12% of the patients had culture reports of which majority (77.8%) were available after 72 h of the initial antibiotic start. Antimicrobial susceptibility test was done for 83.3% of the positive cultures. Although 99.5% of the patients were initially placed on empiric therapy, adjustment was done in 114 (30.9%) of the patients. Among these patients with adjusted therapy, changes were unrelated to microbiologic reasons in 103 (90.4%) patients. None of these changes were for the reason of streamlining therapy. Prolonged hospital stay (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.2–6.7), senior physician consultation (AOR = 4.1, 95% CI 1.1–17.7) and suspicion of new site of infection (AOR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.2) were positive independent predictors for physicians’ preference in ordering culture.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-018-3782-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Physicians’ utilization, Microbiologic reports, TASH

Introduction

Studies indicated that targeting or adjustment of antibiotic treatment according to the results of antimicrobial susceptibility test results lead to decreased antibiotic use, cost and increased therapeutic efficacy [1, 2]. Though microbiologic reports were expected before the initiation of any antibiotic treatment, published microbiologic guidelines do not specifically state when cultures should be drawn for most clinical conditions; thus, it is generally accepted and taken as the quality of care indicator if drawn and reported before antibiotic startup [3–5]. For initial treatment, however, to avoid bad consequences of delayed therapy while waiting microbiologic reports, immediate and adequate/appropriate empiric therapy is generally recommended in the treatment guidelines. Further, these guidelines state that the empiric therapies should be streamlined on the bases of microbiologic cultures [6, 7].

Because of the challenges of determining true bacteremia for positive microbiologic cultures, physicians are highly ignorant to order cultures or tend to order irregularly. On the other hand, because of the high mortality associated with bacteremia, the dangers of undertreating some infections, or concern about using inappropriate antibiotics, physicians tend to order blood cultures liberally [8–10].

Despite this controversy, physicians had better persistently help to improve and rely on the microbiologic investigations in the way that enable to challenge the risks posed by antimicrobial resistance [1–5]. Although the issue of antimicrobial resistance is critically increasing, there is paucity of published data in the study setting. The main aim of this study is; therefore, to assess physicians’ practice in using microbiologic reports and determinants of their preference in ordering microbiologic cultures in TASH. The results of this study may have paramount importance for physicians, policy makers and patients at large in fighting antimicrobial resistance and routine use of microbiologic reports before prescription of antimicrobial agents.

Main text

Materials and methods

Study setting and context

Institution based prospective observational study design was employed. The study was conducted in TASH from 9 April to 7 July 2014. TASH is a teaching hospital with multiunit services.

Population

All patients (with any age range) attending the medical ward including the medical intensive care unit (ICU) of TASH during the study period and who had suspected systemic bacterial (non-mycobacterial) infection were included. Patients with suspected systemic bacterial infections and dispensed with systemic antibacterial drugs in medical ward during the study period were included. Patients taking anti-mycobacterial agents, non-systemic antibacterial agents, and prophylactic antibacterial agents were excluded.

Data collection

Data abstraction format adopted from the different literatures was used for data collection. Pilot study was conducted prior to actual data collection and adjustments were done accordingly. Data was abstracted from the patient documentation sheet (patient card) and the attached microbiologic reports. For some ambiguities, however, the bedside nurse and the attending physician had been consulted as necessary. The data collectors were four clinical pharmacy staffs at the hospital and they were trained for 2 days. They were assigned for the collection of data under strict supervision of the principal investigators.

Data processing and analysis

The collected data was checked and cleaned for any deficit prior to data entry. Errors in data entry were also checked for accuracy using double data entry technique. Epi info version 7 software was used for data entry and SPSS for windows version 21.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Binary logistic regression models were used to measure the association of dependent and independent variables.

Operational definitions

The following terms are operationally defined for this particular study.

Prolonged stay

Patients stayed in the hospital above the median (> 14 days).

Antibiotics

Refers to drugs used for systemic bacterial infection.

Definitive therapy

The definitive therapy was labeled based on availability of antimicrobial susceptibility test results irrespective of the true or false positivity of microbiologic results.

Adjustment

Changes made on the antibiotic/regimen after 48–72 h of the initial therapy that refers to either of following.

Discontinued: To mean any discontinuation of all antibiotics found to be unnecessary (e.g. no suspected infection).

Modified: To mean either de-escalation (narrowing by either discontinuation of either agent or using the narrower spectrum option) or broadening (addition or using a much broader spectrum instead or starting a new cycle of treatment after a day and before 7 days of completion of the first course of treatment period) of therapy.

Results

Admission characteristics

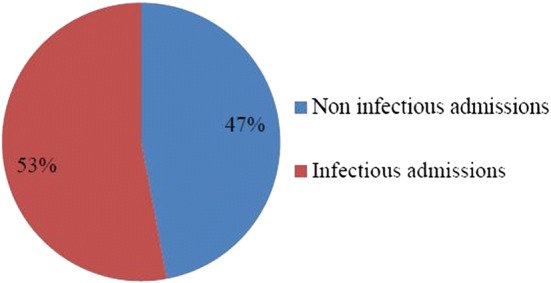

Six hundred ninety-seven patients (626 in the wards and 71 in the ICU) were admitted to the 120 bed medical ward and 6 bed medical ICU during the data collection period. Among these, 369 patients had suspected systemic bacterial infections during or after admission (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Admission characteristics of hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital

Socio-demographic and disease related factors

Majority of the patients with suspected infection were adults in the age range of 18–64 with mean age of 39.8. The median hospital stay length of the patients was 14 days ranging from 3 to 60 days. More than half of them were females. Above 70% of the patients had suspected infection on admission (Table 1). Pneumonia, 48.0%, was the major infection suspected followed by sepsis, 13.0%, and urinary tract infections, 12.5% (Additional file 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and disease related characteristics of hospitalized patients with systemic bacterial infection in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

| Variables | Frequency (N = 369) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | ||

| ≤ 17 | 27 | 7.3 |

| 18–64 | 287 | 77.8 |

| ≥ 65 | 55 | 14.9 |

| Average age of patient ± SD (range) | 39.8 ± 18.5 (10–85) | |

| Sex of patient | ||

| Female | 191 | 51.7 |

| Male | 178 | 48.2 |

| In hospital length of stay | Median 14 days (range 3–60 days) | |

| Setting | ||

| Medical ICU | 42 | 11.4 |

| Internal medicine | 327 | 88.6 |

| Admission diagnosis | ||

| Infectious | 269 | 72.90 |

| Circulatory | 123 | 33.33 |

| Neoplasm | 100 | 27.10 |

| Signs and symptoms of diseasea | 99 | 26.83 |

| Endocrine and metabolic | 40 | 10.84 |

| Digestive | 30 | 8.13 |

| Genitourinary | 25 | 6.78 |

| Blood related | 26 | 7.05 |

| Respiratory | 27 | 7.32 |

| Other diagnosisb | 27 | 7.32 |

SD standard deviation

aBased on International Classification of Disease (ICD 10) criteria referrers to the signs and symptoms of the underlying disease (e.g. hemiparesis, secondary to hypertension) that was not classified elsewhere under the primary admission diagnosis but which were the primary reasons for admission

bDrug adverse outcomes (9), seizure/epilepsy (4), gynecology (3), arthritis (2), communicable hydrocephalus (1) cholestatic calculi (1), and injury (2)

Initial therapy and evidences for change

Almost all of the patients were initially placed on empiric therapy. The initial therapy was adjusted in 114 (30.9%) of the patients. Among these patients with adjusted antibiotic changes, the reason of change was not due to microbiologic reasons in 103 (90.4%) patients. The top reasons for change were suspicion of new site infection (32.5%), followed by clinical deterioration (20.2%), intravenous to oral drug switch (18.4%) and senior physician consultation (9.6%) respectively. Microbiologic report accounts only for 9.6% of the changes and all these changes were attributed from a positive culture results, except one, from a negative culture. Furthermore, none of the changes were for the reason of streamlining therapy (Additional file 2).

Microbiological reports and determinants of physicians’ preference

Of the total 369 patients, 91 (24.7%) had microbiologic reports. Seventy-six (83.5%) of them were reported in the wards, and fifteen (16.5%) in ICU. Ten (11.0%) of them had both Gram stain and culture, 46 (50.5%) had only Gram stain and the remaining 35 (38.4%) had only culture (Additional file 3). Most of the cultures, 35 (77.8%), were reported after the antibiotic startup. From 12 positive cultures, antimicrobial susceptibility test was done for 10 (83.3%) of them (Additional file 4).

Prolonged hospital stay (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.2–6.7), senior physician consultation (AOR = 4.1, 95% CI 1.1–17.7) and suspicion of new site infection (AOR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.2) were positive, and presence of HIV infection (AOR = 0.1, 95% CI 0.02, 0.98) were negative independent determinants for physicians’ preference in ordering culture (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis for physicians’ preference in ordering culture among patients with systemic bacterial infections in the internal medicine wards of TASH TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

| Variable | Culture ordered | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Sex of patient | ||||

| Female | 176 (92.1) | 15 (7.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 148 (83.1) | 30 (16.9) | 2.4 (1.2, 4.6)** | 2.0 (.98, 4.2) |

| Length of stay | ||||

| ≤ 14 | 181 (94.8) | 10 (5.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| > 14 | 143 (80.3) | 35 (19.7) | 4.4 (2.1, 9.3)*** | 2.9 (1.2, 6.7)** |

| On admission HIV infection | ||||

| Present | 274 (86.2) | 44 (13.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Absent | 50 (98.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0.1 (0.02, 0.9)* | 0.1 (0.02, 0.98)* |

| Febrile neutropenia | ||||

| Present | 289 (89.2) | 35 (10.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Absent | 35 (77.8) | 10 (22.2) | 2.4 (1.1, 5.2)* | 1.5 (0.6, 3.5) |

| Pleural effusion empyema | ||||

| Present | 320 (88.4) | 42 (11.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Absent | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 5.7 (1.2, 26.4)* | 4.4 (0.6, 31.1) |

| Senior consultation | ||||

| No | 317 (88.5) | 41 (11.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 4.4 (1.2, 15.8)* | 4.1 (1.1. 17.7)* |

| Clinical deterioration | ||||

| Present | 311 (89.1) | 38 (10.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Absent | 13 (65.0) | 7 (35.0) | 4.4 (1.7, 11.7)** | 2.7 (0.9, 7.8) |

| Suspicion of new site infection | ||||

| Present | 296 (90.2) | 32 (9.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Absent | 28 (68.3) | 13 (31.7) | 4.3 (2.0, 9.1)*** | 2.6 (1.1, 6.2)* |

COR crude odds ratio, AOR adjusted odds ratio

* P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001

Discussion

Pneumonia was the most common infection in hospitalized patients in this study which is similar with other studies [11, 12]. Unlike these studies, infection was the primary diagnosis for admission followed by circulatory disorders in the present study. The difference might be due to differences in the prevalence of infectious and non-infectious diseases in different countries.

Empiric therapy was initiated for more than 99% of patients in the wards and all patients in the ICU of the present study. This was in complete disagreement with a study conducted in another teaching hospital [13], where empiric therapy was initiated only for 19.4% of the patients. As per studies, antibiotics ordered empirically were found to be less appropriate than those ordered with evidence of culture and susceptibility reports [14].

Failures to obtain microbiologic cultures represent failed opportunities for guiding antimicrobial therapy [15]. On the other hand, each contaminated culture incurs an additional cost (due to additional diagnostic testing, increased length of stay, unnecessary medication use and associated adverse events) [16]. This implies, besides obtaining microbiologic cultures, appropriate changes according to the microbiologic reports are essential.

One of the important issues in this study is that the microbiologic reports were not appropriately used for therapy adjustment. In the current study all the adjustments were solely attributed to the positive cultures, irrespective of their false or true positivity. Different studies that evaluated outcomes for culture positive and culture negative reports evidenced that patients with culture negative infections differ substantially (had lower severity of illness, hospital mortality, and hospital length of stay) from patients with positive microbiologic cultures [17, 18]. Therefore, antibiotics can safely be discontinued for culture negative reports [1, 2, 17].

Another finding in this study is that most microbiologic cultures (77.8%) were performed after antibiotics were administered. This can potentially decrease culture yield as compared to patients who are not receiving antibiotics [19, 20].

Prolonged in hospital stay (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI 1.2–6.7), senior consultation (AOR = 4.1, 95% CI 1.1–17.7) and suspicion of new site infection (AOR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.2) were positive, and presence of HIV infection (AOR = 0.1, 95% CI 0.02, 0.98) were negative independent predictors for physicians’ preference in ordering culture. This implies that physicians need microbiologic results when patients stay long indication ineffectiveness of prescribed antibiotics and it is usual that physicians must change regimen when new infection is suspected. Presence of HIV infection negatively associated with physicians’ preference in ordering culture in this study. The possible justification may be the fact that HIV patients may show different opportunistic diseases symptoms due to immunosuppression which leads physicians ignorant at one hand and HIV patients are usually prescribed for prophylaxis irrespective of culture results on the other hand.

Conclusion

Generally, physicians’ microbiologic utilization in optimizing antimicrobial therapy was not only suboptimal but also performed liberally. They mainly rely on their clinical judgment than initiating microbiologic orders unless for patients with prolonged hospital stay, suspicion of late onset of new infections and senior physician consultation. In this era of increasing antimicrobial resistance, wider use of microbiologic cultures should be encouraged to ensure targeted therapy and cost reduction, particularly with severely ill hosts. However, microbiologic cultures should be used appropriately to avoid unintended consequences. Regimen changes should be based on antimicrobial susceptibility tests and further large scale researches are recommended.

Limitations

This study has limitations: (1) Specific microbiology specimen sources were mot recorded. (2) The current study did not use any measures to assess the correctness of changes and/or the true or false positivity of microbiologic results.

Additional files

Additional file 1. Types of systemic bacterial infections suspected or proven in hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional file 2. Initial therapy type, type of change and the reasons for change in hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional file 3. The number and type of microbiologic reports available for infected patients followed in medical ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional file 4. Microbiologic reports available and/or used for therapy adjustment in hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: GA. Analyzed the data: GA. Wrote the paper: GA, HMM. Assisted with design, analysis, and interpretation of data: GG, TG, ZT and HMM. A critical review of the manuscript: GA, GG, TG, ZT and HMM. Read and approved the final manuscript: GA, GG, TG, ZT and HMM. Critical appraisal of the manuscript: GA, GG, TG, ZT and HMM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Addis Ababa University postgraduate office for giving us the opportunity to undertake this research and funding. Our sincere and special thanks goes to all authors of references used in advance. We are happy to thank the study participants and data collectors without whom this research could not be a reality. We duly acknowledge the staffs of TASH for their unreserved support and courage.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted after it was ethically reviewed and approved by the Institutional review board (IRB) of Addis Ababa University and Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital. Then a letter informing the respective wards of the hospital were written from the IRB and permission obtained. All the information obtained from the study participants was coded to maintain confidentiality. All participants (aged ≥ 16 years) provided verbal informed consent and the parents/guardians of all participants below the age of 16 provided consent based on local laws. The IRB approved the use of verbal informed consent documented by a witness after the objectives of the study had been explained.

Funding

The source of funding for the research was Addis Ababa University postgraduate office. The funder has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- AST

antimicrobial susceptibility test

- COR

crude odds ratio

- ICU

intensive care unit

- TASH

Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital

Contributor Information

Getachew Alemkere, Email: kume1036@gmail.com.

Getu Gilagil, Email: getuwelde@gmail.com.

Teklu Gebrehiwot, Email: tekluu2020@gmail.com.

Zelalem Tilahun, Email: zelatilahun@gmail.com.

Hylemariam Mihiretie Mengist, Phone: +251910600543, Email: hylemariam@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Berild D, Mohseni A, Diep LM, Jensenius M, Ringertz SH. Adjustment of antibiotic treatment according to the results of microbiologic cultures leads to decreased antibiotic use and costs. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:326–330. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlueter M, Tsu L, James C, Seymann G, Dominguez A. Practice patterns for antibiotic de-escalation healthcare-associated pneumonia. Infection. 2010;38:357–362. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0042-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron EJ, Miller JM, Weinstein MP, et al. Executive summary: a guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2013 recommendations by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM)(a) Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(4):485–488. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van den Bosch CMA, Geerlings SE, Natsch S, Prins JM, Hulscher MEJL. Quality indicators to measure appropriate antibiotic use in hospitalized adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;60(2):281–291. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Bosch CMA, et al. Development of quality indicators for antimicrobial treatment in adults with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:345. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Infectious Diseases Society of America and American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(4):788–802. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00062-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates DW, Cook EF, Goldman L, Lee TH. Predicting bacteremia in hospitalized patients: a prospectively validated model. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(7):495–500. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-7-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth A, Wiklund AE, Pålsson AS, et al. Reducing blood culture contamination by a simple informational intervention. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(12):4552–4558. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00877-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storey, et al. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program on the medical-surgical service of a 100-bed community hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1:32. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camins BC, King MD, Wells JB, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial utilization program on antimicrobial use at a large teaching hospital: a randomized controlled trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(10):931–938. doi: 10.1086/605924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mettler J, Simcock M, Sendi P, et al. Empirical use of antibiotics and adjustment of empirical antibiotic therapies in a university hospital: a prospective observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:7–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erbay A, Bodur H, Akıncı E, Çolpan A. Evaluation of antibiotic use in intensive care units of a tertiary care hospital in Turkey. J Hosp Infect. 2005;59(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiff GD, Wisniewski M, Bult J, Parada JP, Aggarwal H, Schwartz DN. Improving inpatient antibiotic prescribing: insights from participation in a national collaborative. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27:387–402. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates DW, Goldman L, Lee TH. Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization: the true consequences of false-positive results. JAMA. 1991;265:365–369. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460030071031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrew J, Richard M, Scott T, Marin H. A comparison of culture-positive and culture-negative health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2010;137:1638–1652. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rello J, Bodi M, Mariscal D, et al. Microbiological testing and outcome of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003;123(1):174–180. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pazin GJ, Scott S, Thompson ME. Blood culture positivity: suppression by outpatient therapy in patients with bacterial endocarditis. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grace CJ, Lieberman J, Pierce K, Littenberg B. Usefulness of blood culture for hospitalized patients who are receiving antibiotic therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1651–1655. doi: 10.1086/320527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Types of systemic bacterial infections suspected or proven in hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional file 2. Initial therapy type, type of change and the reasons for change in hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional file 3. The number and type of microbiologic reports available for infected patients followed in medical ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Additional file 4. Microbiologic reports available and/or used for therapy adjustment in hospitalized patients in the internal medicine ward of TASH in 2014, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.