Abstract

Operating rooms (ORs) in hospitals are sensitive wards because patients can get infections. This work aimed to characterize the type and concentration of bioaerosols in nine ORs of an educational hospital before and after sterilization and disinfection. During 2017, fungal samples were incubated at 25–28 °C for 3–7 days and bacterial samples at 37 °C for 24–48 h. The study results showed that the concentrations of fungi before cleaning procedures (for both of disinfection and sterilization) were limited from 4.83 to 18.40 CFU/m3 and after cleaning procedures ranged from 1.90 to 8.90 CFU/m3. In addition, the concentrations of bacteria before cleaning procedures were limited 14.65–167.40 CFU/m3 and after cleaning procedures ranged from 9.50 to 38.40 CFU/m3. The difference between the mean concentrations of airborne bioaerosols before and after sterilization was significantly different than the suggested value of 30 CFU/m3 (p ≤ 0.05). The bacterial concentration was higher than the recommended value (30 CFU/m3) in 41% of the ORs. The main fungal species identified in the indoor air of ORs (before vs. after sterilization) were A. fumigatus (25.6 vs. 18.3%), A. Niger (11.6 vs. 5.8%), Penicillium spp. (5.5 vs. 3.3%), Alternaria spp. (2.8 vs. 0.7%), Fusarium spp. (9.7 vs. 3.7%), Mucor spp. (15 vs. 12.7%), Cephalotrichum spp. (1.7 vs. 0.8%), A. Flavus (24.6 vs. 18.5%), Cladosporium spp. (2.6 vs. 0.8%), and Trichoderma spp. (0 vs.0.9%). The growth of biological species even after sterilization and disinfection likely resulted from factors including poor ventilation, sweeping of OR floors, inadequate HVAC filtration, high humidity, and also lack of optimum management of infectious waste after surgery. Designing well-constructed ventilation and air-conditioning systems, replacing HEPA filters, implementing more stringent, frequent, and comprehensive disinfection procedures, and controlling temperature and humidity can help decrease bioaerosols in ORs.

Keywords: Bioaerosol, Operating room, Sterilization, Indoor air, Shiraz

1. Introduction

Bioaerosol concentrations in indoor air, especially hospitals and their operating rooms (ORs), pose a public health issue in developing countries (Napoli et al., 2012; Nourmoradi et al., 2012; Soleimani et al., 2016). Fungal and bacterial bioaerosols can cause acute diseases, infections, asthma, rhinitis, and allergies in indoor air, such as ORs (Azimi et al., 2013; Dales et al., 1991; Goudarzi et al., 2014; Khan and Karuppayil, 2012; Mandal and Brandl, 2011; Saadoun et al., 2008; Soleimani et al., 2016). Patients may also be a source of airborne microorganisms that can affect other vulnerable patients, personnel, and visitors in hospitals (Qudiesat et al., 2009). Fungal and bacterial bioaerosols, especially in hospitals and clinical settings, cause susceptible patients to be exposed to air pollution during surgery (Napoli et al., 2012).

Previous studies have shown that hospital infections are promoted by fungi such as Aspergillus species, Candida albicans, Cladosporium, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Mucorales (Faure et al., 2002; Sautour et al., 2007; Sohrabi et al., 2014). Faure et al. assessed bioaerosol pollution in ORs in France and reported that the predominant species were Penicillium spp., Cladosporium spp., Aspergillus spp., and Aspergillus fumigatus (Faure et al., 2002). Another study evaluated microbe levels in different parts of a hospital and found that the fungal concentration ranged from 0 to 7.33 CFU/m3 in ORs (Ortiz et al., 2009). Concentrations of fungi and bacteria in a hospital in Taiwan ranged between 0 and 319 and 1–423 CFU/m3, respectively (Li and Hou, 2003). Moreover, fungal bioaerosols can be caused colonizing syndromes, such as nosocomial aspergillosis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (Ortiz et al., 2009; Sohrabi et al., 2014). The presence of fungi in hospital wards, particularly ORs, is linked to several factors such as the (i) presence, condition, and activities of patients, (ii) temperature, (iii) inadequate ventilation, (iv) poor air-conditioning systems, (v) humidity, (vi) organic matter (OM) available in materials of walls, (vii) types of surgery, (viii) the season, and (ix) inadequate disinfection (Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Faure et al., 2002; Nourmoradi et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013; Sautour et al., 2007; Wan et al., 2011). The main reason for bacterial contamination in OR air is thought to be surgical site infection after operations (Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Landrin et al., 2005; Napoli et al., 2012).

The goal of this work was to study the type and concentration of bioaerosols in ORs in a major educational hospital in Shiraz, Iran, specifically affiliated with the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. By comparing aerosol characteristics before and after conventional disinfection and sterilization procedures, a goal of this work is to determine how effective such procedures are in eliminating harmful bioaerosol in the indoor environment of a major hospital.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Location

Shiraz is in a semiarid area and the capital of Fars province in southwestern Iran (29 °36′N, 52 °32′ E) with an average elevation of 1500 m above sea level (Dehghani et al., 2018; Delikhoon et al., 2018; Neghab et al., 2017). It is located near Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait and has a total population of 1.3 million (Fig. 1). This study aimed to assess the microbial load, including fungi and bacteria, in the indoor air of nine ORs in an educational hospital in Shiraz, Iran in 2017. Furthermore, patients who check into the hospital typically have diseases such as those related to the cardiovascular system, hemic and lymphatic systems, mediastinum and diaphragm, digestive system (stomach / excision, liver / incision and so on),urinary system (kidney, bladder / excision, cystoscopy / urethroscopy / cystourethroscopy and ureter / incision), male genital system, integumentary system,musculoskeletal system, maternity care and delivery, respiratory system, and female genital system. It should be noted that only general and internal surgeries were performed in the ORs under investigation.

Fig. 1.

Map of Iran and Shiraz indicating the location of the selected hospital.

2.2. Cleaning operating rooms and ventilation

Before surgery, all OR instruments, including chests, tables, and operation beds, were cleaned and disinfected with a Deconex Surface AF (Aldehyde-Free) solution. The floors and walls of the nine studied ORs were also disinfected with a sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution. During and after surgery, OR floors were cleaned by wet mopping (cleaning tool). In addition, ORs were cleaned every Thursday with the following steps: (i) all mattresses, rolls, logo boards, rims, and stretchers were rinsed with detergent and water and disinfected with Deconex 50 AF; (ii) doors and walls were rinsed with detergent and water disinfected using Deconex 50 AF; and (iii) floors and walls were disinfected with the NaOCl solution. Additionally, after sterilization and disinfection, ORs were sterilized with UV irradiation in a short span of time (< 2 h). In addition, this educational hospital has conventional ventilation with HEPA filters. HEPA-filtered laminar air-flow was supplied vertically and downwards to ORs via ceilings. The air change rate was less than 15 h−1 and no recirculation of air occurred.

2.3. Sampling method

A QuickTake-30 sample pump equipped with standard biostage impactor containing 400-holes (BioStage Single-stage Impactor, SKC, Inc., USA) was used for air sampling every twenty minutes at a flow rate of 28.30 L min−1. Relative humidity (%) and temperature (°C) were simultaneously recorded using a portable instrument (Preservation Equipment Ltd, UK) to find the relation between bioaerosol concentrations and environmental conditions. Sabouraud dextrose agar medium (Merck Co, Germany) containing chloramphenicol antibiotic and blood agar medium (Merck Co, Germany) were prepared and used in order to identify and speciate fungal and bacterial bioaerosol species, respectively. Sampling was performed based on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) method every six days between October and November 2017. Every six days, four samples were collected in each OR with two samples obtained before and after sterilization. For the nine total ORs studied, a total of 360 bacterial and fungal samples were obtained between October and November; this consisted of 180 fungi samples collected before and after sterilization and 180 bacteria samples collected before and after sterilization.

Air samples were collected approximately 1.5 m from the floor, which is a representative height at which breathing occurs. At first, the sampler was sterilized with 70% ethanol to remove any contamination after each sampling. Collected samples were immediately sealed and carried to the microbiology laboratory in a cooled box. The fungal samples were incubated at 25–28 °C for 3–7 days, while the bacterial samples were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h. Finally, the concentration of bioaerosols in the plates were counted and reported according to CFU/m3 (Yassin and Almouqatea, 2010). The fungal colonies that appeared on the exposed plates were identified by a microscope at the magnification of ×40. Finally, the slide culture method was used for examination and identification of fungal colonies (Brown and Benson, 2004). Gram staining was used to identify Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria (Schaad et al., 2001).

2.4. Data analysis

SPSS statistical software, version 22, was applied for analyzing data in this study. Data were checked to see the degree to which they exhibited normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Pearson and Spear-man correlation coefficients, the paired sample t-test, and the Wilcoxon test were applied. Finally, figures in this work were produced using GraphPad Prism 7.

3. Results

3.1. Mean number of bacteria

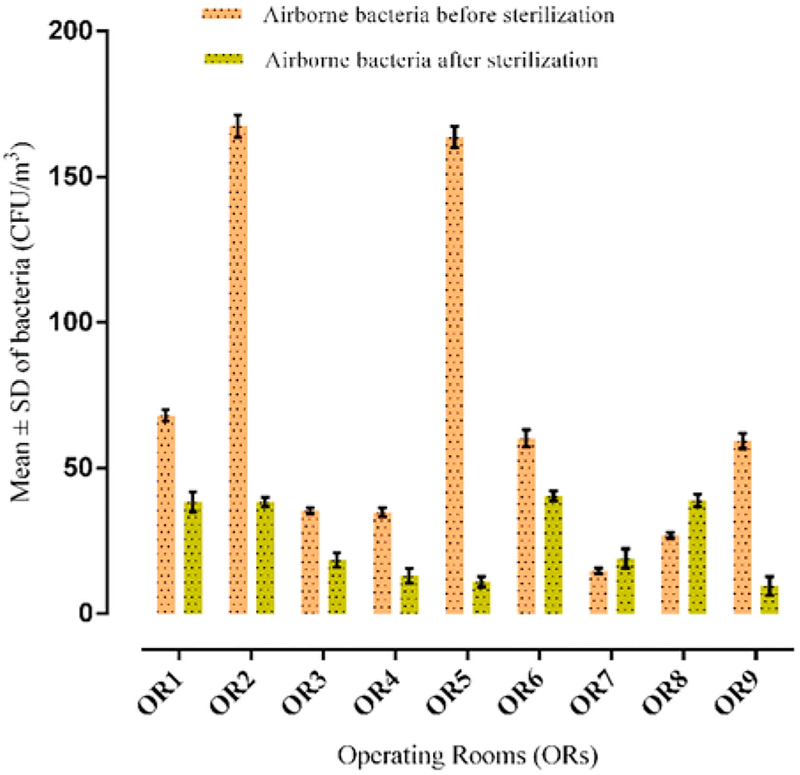

The mean ± standard deviation (SD) number of bacteria before and after disinfection and sterilization is summarized in Fig. 2. The concentrations of bacteria before cleaning procedures (for both of disinfection and sterilization) were limited 14.65–167.40 CFU/m3 and after cleaning procedures ranged from 9.50 to 38.40 CFU/m3. The average concentration of airborne bacteria before and after disinfection and sterilization was significantly higher than the suggested value (Audurier et al., 1985) (30 CFU m−3) (p ≤ 0.05). Both Gram positive and negative bacteria grew on the agar medium in all the ORs. In addition, the results showed that Gram-positive bacteria demonstrate higher concentrations than Gram-negative bacteria in all the ORs. Meteorological profile period in hospital including temperature and relative humidity were, respectively, 35 ± 0.80 °C and 18 ± 1% during the study. In addition, the mean temperature and humidity in the ORs’ air were 23.4 ± 2.1 °C and 34.4 ± 9.7%, respectively, before disinfection and sterilization; analogous values after cleaning were 23.5 ± 2.1 °C and 39.4 ± 9.9%. The lowest and highest humidities and temperatures were 24% and 20 °C (before disinfection and sterilization), and 50% and 27 °C (after disinfection and sterilization). The results of Pearson’s correlation analysis demonstrated that environmental conditions (humidity and temperature) had significant relationships with the concentration of airborne bacteria before disinfection and sterilization (p ≤ 0.05). However, this correlation was not found for temperature after disinfection and sterilization (p = 0.388), while it was observed for humidity (p ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 2.

The mean ± SD of bacteria in indoor air of ORs before and after disinfection and sterilization.

3.2. Mean number of fungi

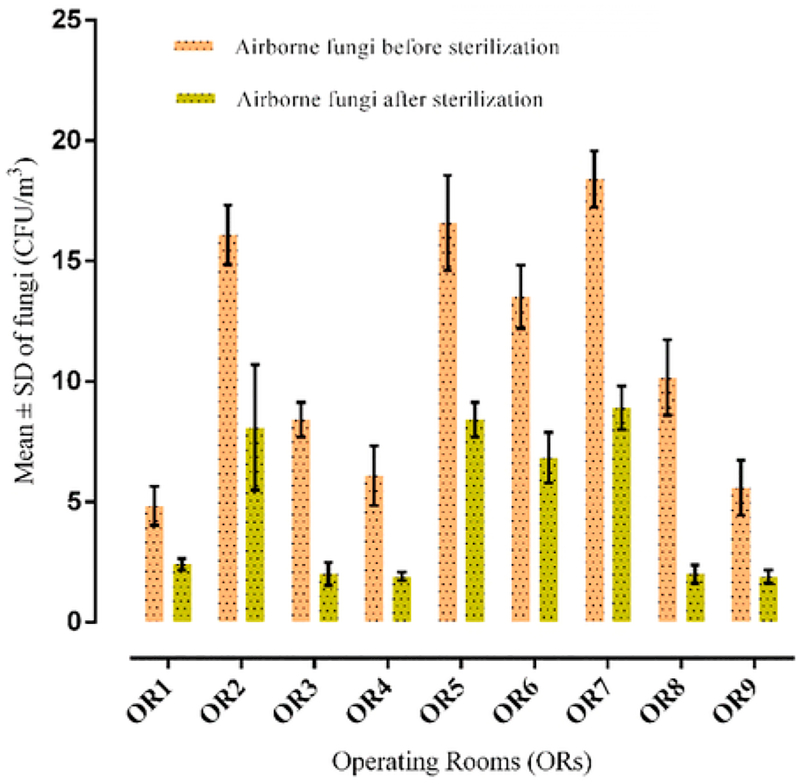

The mean ± SD of fungi before and after disinfection and sterilization is summarized in Fig. 3. The concentrations of fungi before cleaning procedures (for both of disinfection and sterilization) were limited from 4.83 to 18.40 CFU/m3 and after cleaning procedures ranged from1.90 to 8.90 CFU/m3. The mean concentration of airborne fungi was11.06 ± 4.01 CFU/m−3 before and 4.71 ± 1.24 CFU/m−3 after cleaning procedures. The difference between the mean concentrations of fungi before and after disinfection and sterilization exhibited no significant difference (p ≥ 0.05). However, the mean concentrations of airborne fungi before and after disinfection and sterilization were significantly lower compared to the suggested value of 30 CFU/m−3 (Audurier et al., 1985) (p ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The average ± SD of fungi in indoor air of ORs before and after disinfection and sterilization.

Based on Pearson’s correlation analysis, temperature and humidity did not exhibit a significant relationship with the concentration of airborne fungi before disinfection and sterilization (p ≥ 0.05). However, they had significant relationships with the concentration of airborne fungi after disinfection and sterilization (p ≤ 0.05).

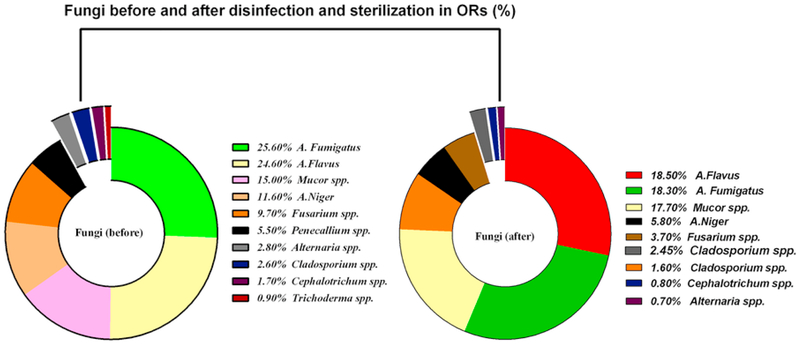

The percentages of fungi and fungi genera in the ORs air before and after disinfection and sterilization are shown in Fig. 4. The main fungal species before sterilization were A. fumigatus (25.6%), A. Niger (11.6%), Penicillium spp. (5.5%), Alternaria spp. (2.8%), Fusarium spp. (9.7%), Mucor spp. (15%), Cephalotrichum spp. (7.9%), A. Flavus (24.6%), Cladosporium spp. (2.6%), and Trichoderma spp. (0.9%). On the other hand, the main fungal species detected after disinfection and sterilization wereA. fumigatus (18.3%), A. Niger (5.8%), Penicillium spp. (3.3%), Alternaria spp. (0.7%), Fusarium spp. (3.7%), Mucor spp. (12.7%), Cephalotrichum spp. (0.8%), A. Flavus (18.5%), and Cladosporium spp. (1.6%).

Fig. 4.

The percentage of fungi and fungi genera in indoor air of ORs before (left) and after (right) disinfection and sterilization.

4. Discussion

All parts of hospitals, particularly ORs, are sensitive environments that contain a variety of bioaerosol species. Bacteria and fungi are the main species of bioaerosols in ORs that are transported through air, including from the outdoor environment (Soleimani et al., 2016), and introduced via visitors and hospital personnel via respiration, coughing, and sneezing (Saadoun et al., 2008). Thus, it is important to assess the efficacy of disinfection and sterilization procedures in minimizing bioaerosol concentrations in hospitals rooms, particularly ORs (Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Landrin et al., 2005). There are limited specific standards set for the indoor air of ORs to prevent exposure to bioaerosols (Landrin et al., 2005). However, general guidelines do exist for indoor air, such as how the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) recommends values to be below 500 CFU/m3. The World Health Organization recommended that microbial counts in general workplaces to be less than 300 CFU/m3, and to be less than 100 CFU/m3 for individuals with immunosuppression issues. In addition, guidelines proposed by the UK and Switzerland have been set at 35 CFU/m3 and 25 CFU/m3, respectively, for bacterial density in ventilated ORs (Landrin et al., 2005). Other work also disclosed that bacterial density should not exceed 30 CFU/m3 in a modern ventilated OR (Audurier et al., 1985). Iran has its own standard for hospital indoor air quality (IAQ) and has adopted guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The requirements suggested by the CDC, HICPAC, and NIOSH, also used here are as follows (Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Friberg et al., 1999; Sehulster et al., 2003; Streifel, 1999): the room air temperature of 20–25 °C, relative humidity of 30–60%, filtration provided for 90% of air, air change rate of 15 h−1, and no recirculation of the air. Our results also reveal that the concentrations of fungi before cleaning procedures (for both of disinfection and sterilization) were limited from 4.83 to 18.40 CFU/m3 and after cleaning procedures ranged from 1.90 to 8.90 CFU/m3. For context, ORs in a training hospital in Nigeria exhibited fungi concentrations between 15 and 24.3 CFU/m3 (Ekhaise et al., 2010). Furthermore, fungi concentrations ranged between 80 and 148 CFU m−3 in ORs of various hospitals in northern Jordan (Saadoun et al., 2008).

The findings of this work demonstrated that the concentrations of bacteria were more than that of airborne fungi in the ORs, which is consistent with the findings of Ekhaise et al. in a teaching hospital in Nigeria (Ekhaise et al., 2010). The concentration of bacteria measured in this work was higher compared to a previous study performed by Qudiesat et al. in a private and a public hospital in Zarqa, Jordan (Qudiesat et al., 2009). In our study, bacterial and fungal density was lower than the ACGIH recommended values (500 and 100 CFU m−3, respectively) in all ORs (Ammann, 1998; Darvishzadeh et al., 2013). The concentration of airborne bacteria was higher than the recommended value (30 CFU/m−3) in the air of some ORs (Audurier et al., 1985). The difference in bacterial and fungal densities before and after sterilization can be attributed to individuals’ frequent trips in and out of ORs in addition to the type of operations (Kim et al., 2010).

The results of this work demonstrated a significant difference between both the average number of bacteria and fungi in the air of ORs and the suggested values before and after sterilization (p ≤ 0.05). However, contradictory results were reported by Nourmoradi et al. in 2012 and Hoseinzadeh et al. in 2013 in educational hospitals of Isfahan and Hamedan, Iran (Hoseinzadeh et al., 2013; Nourmoradi et al., 2012).

Our findings indicated that the concentration of bioaerosols decreased slightly after sterilization, disinfection, and washing apparatuses and beds. The concentration of bioaerosols in the ORs after sterilization and disinfection might be due to high humidity (more than 60% after sterilization), occupants’ density, HEPA filters needing to be replaced, poor ventilation, air changes per hour being less than standard levels (15 h−1) (Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Streifel, 1999), inadequate disinfection, UV irradiation in short time (less than 2 h), and hospital building’s age. Among these factors, humidity, insufficient disinfection, UV irradiation, and the lack of proper ventilation were most responsible for the number of fungi and bacteria aerosols after sterilization (Chow and Yang, 2005; Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Friberg et al., 1999; Hoffman et al., 2002; Park et al., 2013; Tesfaye et al.,2015). Park et al. (2013), Tesfaye et al. (2015) and Hoffman et al. (2002) showed that the lack of proper ventilation, moisture, and unfiltered air were most responsible for microbial growth in hospital wards, which is in line with the findings of the present research (Dharan and Pittet, 2002; Hoffman et al., 2002; Park et al., 2013; Tesfaye et al.,2015).

Qudiesat et al. (2009) and Obbard and Fang (2003) also reported that humidity was the key to growth and distribution of airborne fungi in hospitals (Obbard and Fang, 2003; Qudiesat et al., 2009). Similarly, other studies have concluded that humidity was the main parameter affecting the bioaerosol concentrations in hospital lobbies and cleaning rooms (Ekhaise et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2007; Park et al., 2013). Moreover, a previous study demonstrated that airborne contamination was higher in old versus new ORs, which is consistent with the results of this work (Audurier et al., 1985).

In the present research, the main fungal species detected in indoor air of ORs were Aspergillus sp. Penicillium sp., Cladosporium sp., and Fusarium sp. Others also identified the same microbial isolates in ORs of different hospitals in Seoul (South Korea), Rome (Italy) and Northern Jordan (Kim et al., 2010; Perdelli et al., 2006; Saadoun et al., 2008).

Additionally, our results showed that the amount of fungi decreased (slightly) after sterilization, which is in agreement with the findings of previous research in ORs of hospital in Murcia, Spain (Ortiz et al., 2009). This low growth might result from the fact that the lack of proper ventilation and air change rate were less than recommended standard values. Also, likely contributors could have been UV irradiation in short time, sweeping of the ORs floors, transport of spores via air conditioning with poor filtration, high humidity that is more than 60% after sterilization, crowds of patients, and also lack of optimum management of infectious waste after surgery (during the collection, transportation, and temporary storage).

5. Conclusions

The findings of this work showed that bacterial concentration was higher than the suggested value of 30 CFU m−3 in the air of a significant number of ORs examined. In spite of sterilization, different types of fungi, Gram-positive bacteria, and Gram-negative bacteria were detected in the ORs. The main fungal species detected in indoor air of ORs were A. fumigatus, A. Niger, Penicillium spp., Alternaria spp., Fusarium spp., Mucor spp., Cephalotrichum spp., A. Flavus, Cladosporium spp., and Trichoderma spp. In addition, the results revealed that there was growth of bioaerosols after sterilization, disinfection, and washing the apparatuses and beds. Reasons include high humidity, poor ventilation, insufficient disinfection, sweeping of floors, lack of optimum management of infectious waste after surgery, and UV irradiation. Therefore, designing well-constructed ventilation and air-conditioning systems, implementing more stringent, frequent, and comprehensive disinfection and cleaning procedures, and controlling temperature and humidity can help reduce bioaerosol levels in ORs.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and Health Services (project No. 92-01-21-5904). AS acknowledges Grant 2 P42 ES04940–11 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program, NIH. The authors thank Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and the educational hospital for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Competing interest

“The authors declare that they have no competing interests.”

References

- Ammann H, 1998. Why ACGIH Bioaerosol Committee does not recommend TLVs for bioaerosols. In: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Bioaerosols, Fungi and Mycotoxins: Health Effects, Assessment, Prevention and Control, pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Audurier A, et al. , 1985. Bacterial contamination of the air in different operating rooms.Rev. D.’Epidemiol. Et. De. Sante Publique 33, 134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi F, et al. , 2013. Fungal air quality in hospital rooms: a case study in Tehran, Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng 11, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AE, Benson HJ, 2004. Benson’s microbiological applications: laboratory manual in general microbiology, Short Version. McGraw-Hill Science, Engineering & Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Chow T, Yang X, 2005. Ventilation performance in the operating theatre against airborne infection: numerical study on an ultra-clean system. J. Hosp. Infect 59, 138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dales RE, et al. , 1991. Respiratory health effects of home dampness and molds among Canadian children. Am. J. Epidemiol 134, 196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishzadeh N, et al. , 2013. Evaluation of bioaerosol in a hospital in Tehran. Iran. J. Health Environ 6, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani M, et al. , 2018. Corrigendum to “Characteristics and health effects of BTEX in a hot spot for urban pollution”[Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf 155 (2018) 133–143]. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delikhoon M, et al. , 2018. Characteristics and health effects of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde in an urban area in Iran. Environ. Pollut [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharan S, Pittet D, 2002. Environmental controls in operating theatres. J. Hosp. Infect 51, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekhaise F, et al. , 2008. Hospital indoor airborne microflora in private and government owned hospitals in Benin City, Nigeria. World J. Med Sci 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ekhaise F, et al. , 2010. Airborne microflora in the atmosphere of an hospital environment of University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Benin City, Nigeria. World J. Agric. Sci 6, 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Faure O, et al. , 2002. Eight-year surveillance of environmental fungal contamination in hospital operating rooms and haematological units. J. Hosp. Infect 50, 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg B, et al. , 1999. Correlation between surface and air counts of particles carrying aerobic bacteria in operating rooms with turbulent ventilation: an experimental study.J. Hosp. Infect 42, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi G, et al. , 2014. Particulate matter and bacteria characteristics of the Middle East Dust (MED) storms over Ahvaz, Iran. Aerobiologia 30, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P, et al. , 2002. Microbiological commissioning and monitoring of operating theatre suites. J. Hosp. Infect 52, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinzadeh E, et al. , 2013. Evaluation of bioaerosols in five educational hospitals wards air in Hamedan, During 2011–2012. Jundishapur J. Microbiol 6. [Google Scholar]

- Khan AH, Karuppayil SM, 2012. Fungal pollution of indoor environments and its management. Saudi J. Biol. Sci 19, 405–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KY, et al. , 2010. Distribution characteristics of airborne bacteria and fungi in the general hospitals of Korea. Ind. Health 48, 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrin A, et al. , 2005. Monitoring air sampling in operating theatres: can particle counting replace microbiological sampling?. J. Hosp. Infect 61, 27–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LD, et al. , 2007. Risk of bioaerosol contamination with Aspergillus species before and after cleaning in rooms filtered with high-efficiency particulate air filters that house patients with hematologic malignancy. Infect. Control 28, 1066–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-S, Hou P-A, 2003. Bioaerosol characteristics in hospital clean rooms. Sci. Total Environ 305, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal J, Brandl H, 2011. Bioaerosols in indoor environment-a review with special reference to residential and occupational locations. Open Environ. Biol. Monit. J 4, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C, et al. , 2012. Air sampling methods to evaluate microbial contamination in operating theatres: results of a comparative study in an orthopaedics department. J. Hosp. Infect 80, 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neghab M, et al. , 2017. Exposure to cooking fumes and acute reversible decrement in lung functional capacity. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med 8, 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourmoradi H, et al. , 2012. Evaluation of bio-aerosols concentration in the different wards of three educational hospitals in Iran. Int. J. Environ. Health Eng 1, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Obbard JP, Fang LS, 2003. Airborne concentrations of bacteria in a hospital environment in Singapore. Water, Air, Soil Pollut 144, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz G, et al. , 2009. A study of air microbe levels in different areas of a hospital. Curr. Microbiol 59, 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D-U, et al. , 2013. Assessment of the levels of airborne bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and fungi in hospital lobbies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 541–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdelli F, et al. , 2006. Fungal contamination in hospital environments. Infect. Control 27, 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qudiesat K, et al. , 2009. Assessment of airborne pathogens in healthcare settings. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res 3, 066–076. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I, et al. , 2008. Concentrations of airborne fungal contaminations in the medical surgery operation theaters (OT) of different hospitals in northern Jordan. Jordan J. Biol. Sci 1, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sautour M, et al. , 2007. Prospective survey of indoor fungal contamination in hospital during a period of building construction. J. Hosp. Infect 67, 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad NW, et al. , 2001. Laboratory Guide for the Identification of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. American Phytopathological Society (APS Press). [Google Scholar]

- Sehulster L, et al. , 2003. Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Report. Recomm. Rep. Rr. 52. [PubMed]

- Sohrabi N, et al. , 2014. Evaluation of airborne fungal pollution in the burn ward of Imam Khomeini hospital, the referral burn center in the west of Iran. J. NI 1. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani Z, et al. , 2016. Impact of Middle Eastern dust storms on indoor and outdoor composition of bioaerosol. Atmos. Environ 138, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Streifel A, 1999. Design and maintenance of hospital ventilation systems and the prevention of airborne nosocomial infections Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye T, et al. , (2015). Microbial contamination of operating Theatre at Ayder Referral Hospital, Northern Ethiopia.

- Wan G-H, et al. , 2011. Long-term surveillance of air quality in medical center operating rooms. Am. J. Infect. Control 39, 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassin M, Almouqatea S, 2010. Assessment of airborne bacteria and fungi in an indoor and outdoor environment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol 7, 535–544. [Google Scholar]