Abstract

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri, describes a disease of poorly understood pathophysiology with a specific set of signs and symptoms including potentially irreversible blinding visual loss. Optic nerve sheath fenestration (ONSF) is a well-described surgical treatment for patients with IIH and progressive visual loss despite maximally tolerated medical therapy. A number of optic nerve access procedures have been described including medial transconjunctival, superomedial lid crease, and lateral orbitotomy with and without bone takedown. The purpose of this report is to describe a revised lateral approach for temporal optic nerve access that obviates the need to traverse through the intraconal fat of the central surgical space in the previously described lateral approach techniques.

Keywords: idiopathic intracranial hypertension, pseudotumor cerebri, optic nerve sheath fenestration, lateral orbitotomy

Precis

A revised lateral approach to optic nerve sheath fenestration offers effective and efficient access to the nerve and serves as an alternative to the more popular medial orbitotomy approach, particularly in re-operations following closure of the medial fenestration site.

Introduction

When declining visual function is demonstrated in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) despite optimal medical therapy, surgical intervention in the form of optic nerve sheath fenestration (ONSF) or CSF diversion via neurosurgical shunting is indicated to preserve vision.1, 2 Patients with hemodynamically significant cerebral sinus stenoses may also benefit from endovascular stenting.3 External lumbar drain placement may be used in an inpatient setting to temporarily control intracranial pressure (ICP). 4 ONSF is a minimally invasive procedure with a low rate (<2% in one meta-analysis)5 of major visual complications and may be performed on an outpatient basis; however, patients with significantly elevated opening pressures (>50 cm H2O) and refractory headache may ultimately require more invasive neurosurgical shunting.6

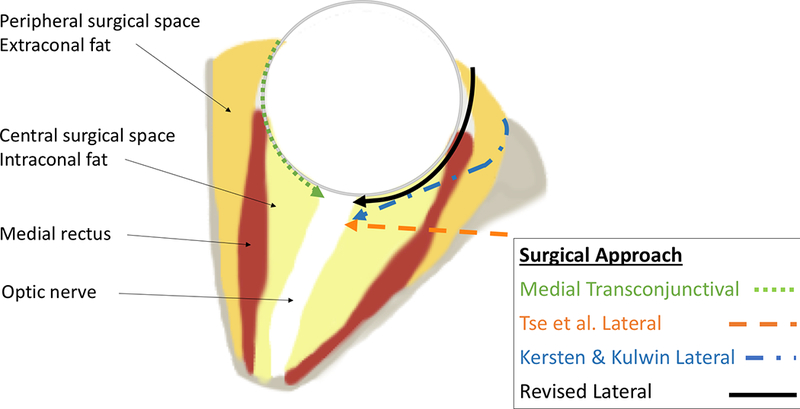

A variety of techniques for optic nerve access to create a sheath window or slit fenestration have been described, each with inherent advantages, disadvantages, and possible complications.7 Surgeon preferences include the use of an operating microscope, the type of fenestration performed (slits versus dural/arachnoid window), and the method of accessing the optic nerve. Possible anatomical approaches include medial transconjunctival orbitotomy with8 or without medial rectus takedown9, via a superomedial lid crease incision10, or via a lateral orbitotomy with11 or without bone takedown.12 The medial transconjunctival orbitotomy is typically cited as the most common approach.7 Tse et al. described the first feasible lateral approach for ONSF in 1988 as an update of Davidson’s original investigative technique13 by utilizing a standard lateral orbitotomy with bone takedown, updated instruments, and an operating microscope. This approach afforded a wide surgical field with direct perpendicular access to the peribulbar bulbous portion of the optic nerve and did not require takedown of a rectus muscle. Disadvantages included a skin incision, increased operative time required to manipulate the bone of the lateral orbital rim, difficulty locating the optic nerve in traversing the orbital fat in the central surgical space, and the potential for injury to the ciliary ganglion.11

Kersten and Kulwin subsequently reported a revised lateral approach in 1993 that obviated lateral orbital bone takedown but accessed the lateral orbital rim through a canthotomy incision. A 2cm subperiosteal dissection was performed starting at the lateral orbital rim and the periorbita was opened using a T-shaped incision with silk suture tagging of the periorbital flaps. The lacrimal gland was retracted followed by dissection medially through the intraconal orbital fat to reach the optic nerve for fenestration. This ostensibly combines the advantageous perpendicular view of the lateral nerve to the ease of operation from the medial approach.12 Despite this revised lateral approach to the nerve, most surgeons have continued to prefer a medial approach likely due to the increased operating time and complexity required to manipulate the periorbita and lacrimal gland and to dissect through the fat compartment in the central surgical space. 7 Herein, we describe a modified lateral approach for temporal optic nerve access. Using the curvature of the episcleral surface as the anatomical glide path, intraconal fat dissection is minimized and the optic nerve-scleral junction can easily be identified. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Axial cut through the mid-orbit demonstrating the 3 previously reported approaches to the optic nerve (dashed lines) as well as the revised lateral approach (solid line).

Surgical Technique

Surgery is performed under general anesthesia. A surgical headlight and magnifying surgical loupes are worn to aid visualization but an operating microscope is not required for any portion of the procedure. A small 5mm lateral canthotomy is performed using 1–2 snips with Stevens or Westcott tenotomy scissors. Inferior or superior cantholysis is not required. (Fig. 2a) The temporal bulbar conjunctival edge is identified and elevated from the underlying body of the lateral rectus muscle using a pair of 0.3mm forceps. A horizontal bulbar conjunctival incision is made from the lateral canthus to the limbus and then Tenon’s capsule is divided and dissected freely from the globe inferiorly and superiorly using Stevens scissors in the manner similar to clearing the temporal quadrants in an enucleation procedure. (Fig. 2b) An inferior conjunctival and Tenon’s relaxing incision is made at the limbus using Westcott scissors. The lateral rectus is isolated on a muscle hook and the surrounding fascial attachments are bluntly dissected posteriorly using cotton-tipped applicators. There is no need to tag the lateral rectus with a traction suture. (Fig. 2c)

Figure 2.

The revised lateral approach begins with a small lateral canthotomy without cantholysis (A). The conjunctiva and Tenon’s is then elevated and divided in continuation with the canthotomy (B). Care is taken to avoid damage to the insertion of the lateral rectus muscle which is isolated on a muscle hook after the lateral quadrants have been cleared with Stevens scissors in the manner of an enucleation procedure (C).

The intraconal dissection is best approached through the superotemporal quadrant and begins by introducing a pair of 7.25mm malleable retractors above the superior edge of the lateral rectus muscle. The retractors are bent in an “L” shape configuration to optimize visualization during intraconal dissection. Both edges of the malleable are always in contact with the episcleral surface of the globe to guide the path of dissection. With the nasal edge of the malleables in contact with the episcleral surface, the blades are retracted in a superior-inferior direction to avoid exerting pressure on the globe. The blades should be positioned with the pupil as the constant central reference point. Once the equator of the globe is reached, a vortex vein will become apparent to indicate a change in the curvature of the globe. The direction of the dissecting tips of the malleable should also change slightly to conform to the changing curvature of the globe. By following the curvature of the posterior scleral surface, the junction of the peribulbar optic nerve should become visible with the adjacent posterior ciliary vessels. The periorbita and lacrimal gland are thus bypassed and left undisturbed. A pair of ½ inch dry neurosurgical cottonoid are inserted into the inter-malleable space and the malleables are repositioned to retract against the cottonoids. (Fig. 3a) The dry cottonoids are used to prevent the fat from billowing over the edges of the malleables to obstruct the path of intraconal dissection. The septae within the intraconal fat directly overlying the peribulbar optic nerve are split in an anterior-posterior direction with a pair of Freer periosteal elevators moving in opposite directions. The cleavage plane in the intraconal fat overlying the optic nerve is secured by replacing the tip of each malleable into the space. This cleavage plane should be in alignment with the pupil, and the space is enlarged by the retracting the malleable blades. The enlarged space is secured by inserting a pair of new dry cottonoids and repositioning the malleable blades over the cottonoids. Residual globules of fat overlying the bulbous portion of the optic nerve can be gently dissected off the nerve with a Freer periosteal elevator. Likewise, the posterior ciliary vessels may be carefully pushed aside using the Freer elevator to expose an unimpeded view of the optic nerve sheath. (Fig. 3b)

Figure 3.

Blunt dissection with thin, narrow malleable retractors along the episcleral surface in the superotemporal quadrant above the lateral rectus is used to reach the posterior globe. Dry 1⁄2” neurosurgical cottonoids are used to retract the fat and aid visualization (A). With the pupil as a reference point, the optic nerve sheath is easily located (B).

After clearing an area free of epidural vessels, the optic nerve sheath on the bulbous segment is grasped with a microsurgical alligator forceps and gently lifted away from the underlying optic nerve proper. A transverse incision is made on the tented sheath using a curved Yasargil bayonet scissors until a fluid gush is observed. While grasping the dural sheath, one blade of the scissors is inserted into the subarachnoid space without touching the pial surface, and an anterior-posterior dural-arachnoid incision is made. A second parallel incision is made at the opposite corner of the original transverse incision. The dural-arachnoid window is completed when a posterior transverse cut is made at the base of the flap. (Fig 4)

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram representing manipulation and fenestration of the optic nerve sheath. Beginning at top-left, the dura and arachnoid are grasped together with forceps perpendicular to the axis of the optic nerve. The dura and arachnoid are incised with microsurgical scissors until a fluid gush is observed (top-right). Vertical back cuts are then made in parallel with the axis of the optic nerve and the sheath window is then amputated transversely at its posterior base (bottom-right).

Should bleeding occur from one of the epidural vessels, bipolar cautery should be avoided on the optic nerve dural sheath surface. A dry cottonoid or a cotton-tipped applicator can be placed over the bleeder with gentle pressure for 30 seconds. The bleeding should stop, but if it persists, pressure should be applied for an additional 30–60 seconds. Once hemostasis is ensured, the malleable retractors and cottonoids are removed. The conjunctiva is then reapproximated at the limbus using an interrupted pass of 6–0 plain gut suture incorporating a small episcleral bite to prevent conjunctival retraction. The remainder of the conjunctiva is then closed using running 6–0 plain gut. The lateral canthus is reformed using a buried interrupted pass of 5–0 polyglactin 910 through the superior and inferior crura of the lateral canthal tendon and then the skin is closed with interrupted 6–0 plain gut. Intraconal dissection through the inferotemporal quadrant is also possible, but the body of the inferior oblique muscle may obscure the continuity of the scleral surface view in some cases.

Discussion

Techniques for ONSF have evolved since deWecker’s original 1872 description of blindly fenestrating with a sheathed neurotome through the inferotemporal fornix sans anesthesia.14 The utility of fenestrating the optic nerve for the treatment of papilledema was demonstrated by Hayreh’s seminal work using rhesus monkeys in the 1960s. Modern ONSF is a remarkably safe and effective procedure performed on an outpatient basis for patients with vision threatening papilledema. 8, 15–24 Although ONSF does not significantly change ICP25, 26, it does effectively decompress the optic nerve sheath locally leading to stabilization or improvement in vision.1, 2, 8, 15, 22, 25–29The functional mechanism of ONSF has been debated. 18 One theory posits that fenestration works via subarachnoid scarring at the site of fenestration and subsequent shifting of the intracranial pressure gradient to a more posterior portion of the optic nerve. 30, 31 However, multiple subsequent studies and observations have lent credence to the egress theory of fenestration wherein CSF drains from the fenestration site through either a direct fistula or an enclosed bleb of fibrosis. 18, 32–35 It is entirely possible that filtration is achieved via both outlets, i.e. immediately post-operatively through a direct fistula until adequate fibrotic tissue forms to encapsulate the surgical site. This theory is supported by post-operative neuroimaging studies demonstrating the formation of well-circumscribed fluid collections at the site of prior fenestration 36, 37, bilateral improvement in vision and optic nerve edema despite unilateral surgery.38, and reports of decreased headache symptomatology following ONSF. 17, 19, 22, 39, 40, 41 Although there is no large randomized controlled trial data available, ONSF success rates (as defined by durable patient improvement in visual function via best corrected visual acuity and/or visual field testing) are high. In the largest available case series of 578 eyes in 331 patients, stable or improved vision and visual fields was seen in 94.4% and 95.9% of eyes respectively.28

Although primary fenestration is a highly successful procedure, there are situations in which a slit or window procedure fails to effect resolution of optic disc edema and visual field deterioration continues. Fenestration failure is thus defined by progressive visual dysfunction despite prior fenestration placement and is likely related to the interplay between fibrosis and at the surgical site and elevated intracranial pressure; a functioning fenestration may be rendered obsolete by progressive scarring and obliteration of the egress of CSF over time or the intracranial pressure may subsequently rise such that the egress capabilities of the fenestration are no longer capable of protecting the adjacent optic nerve.

In rare cases of fenestration failure, a second fenestration may be necessary. Successful secondary fenestration for deterioration of vision following successful primary fenestration has been previously reported. Moreau et al’s cohort included 15 eyes of 11 patients who underwent secondary surgery at an average of 823 days after their initial operation (range 49 – 3703); 14 eyes showed stable or improved vision.28 Spoor et al. similarly reported 13 eyes of 11 patients with 12 eyes demonstrating surgical success with an average reoperation time of 14.5 months (range 2–21).42 Both cohorts underwent primary and secondary fenestration via a medial transconjunctival approach and both authors noted the technical difficulty inherent in traversing the scarred tissue from the primary surgery. Whereas all of the patients in Moreau et al’s cohort underwent window fenestration, Spoor et al’s cohort included a mixture of patients who received one or more slit fenestrations or a window fenestration; unfortunately, the type of fenestration utilized for each patient was not reported.

If a patient had a prior medial or superomedial approach, we prefer to perform the second fenestration procedure on the side of the optic nerve without prior tissue manipulation in order to avoid the scarred tissue planes associated with revisional surgery. Typically, orbital fat is adherent to the dural sheath at the site of previous slit incisions or dural window, and significant dissection is necessary to clear an area of optic nerve sheath for a fresh fenestration.

The temporal approach described here provides a quick access to the undisturbed dural surface of the optic nerve 180 degrees away from the site of previous fenestration failure. (Figure Draft) Using the episcleral surface as the glide path to reach the optic nerve obviates tedious dissection from a subperiosteal incision through the orbital fat in the extraconal and intraconal compartments. Furthermore, dissection along the episcleral surface using the pupil as the center of reference to orient the direction of intraconal dissection allows the nerve to be easily identified; one rarely dissects “off course” above or below the nerve using this method.

The steps in the revised lateral approach for optic nerve exposure are similar to the steps of an enucleation procedure familiar to orbital surgeons. The temporal access technique offers a more direct, perpendicular view of the optic nerve compared to the oblique view from a medial approach and no rectus muscle disinsertion is required. This technique can be used as the primary approach for optic nerve access for fenestration or as a secondary approach to a new site on the nerve for re-fenestration. This temporal transconjunctival approach is also useful for optic nerve biopsy or removing masses in the temporal extraconal and intraconal compartments.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

This work was supported in part by: NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801; Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant, Inc, New York, New York; and the Dr. Nasser Ibrahim Al-Rashid Orbital Vision Research Fund. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

References

- 1.Goh KY, Schatz NJ, Glaser JS. Optic nerve sheath fenestration for pseudotumor cerebri. J Neuroophthalmol 1997;17(2):86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudumbai RC. Optic nerve sheath fenestration: indications, techniques, mechanisms and, results. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2014;54(1):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radvany MG, Solomon D, Nijjar S, et al. Visual and neurological outcomes following endovascular stenting for pseudotumor cerebri associated with transverse sinus stenosis. J Neuroophthalmol 2013;33(2):117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiramongkolchai K, Buckley EG, Bhatti MT, et al. Temporary Lumbar Drain as Treatment for Pediatric Fulminant Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol 2017;37(2):126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satti SR, Leishangthem L, Chaudry MI. Meta-Analysis of CSF Diversion Procedures and Dural Venous Sinus Stenting in the Setting of Medically Refractory Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36(10):1899–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson ME, Moreau A, O’Meilia R, et al. The Relationship Between Optic Nerve Sheath Decompression Failure and Intracranial Pressure in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol 2016;36(3):246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobel RK, Syed NA, Carter KD, Allen RC. Optic Nerve Sheath Fenestration: Current Preferences in Surgical Approach and Biopsy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;31(4):310–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galbraith JE, Sullivan JH. Decompression of the perioptic meninges for relief of papilledema. Am J Ophthalmol 1973;76(5):687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai KE, Lao KC, Hildebrand PL, Farris BK. Superonasal Transconjunctival Optic Nerve Sheath Decompression: A Modified Surgical Technique Without Extraocular Muscle Disinsertion. North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society Annual Meeting Rio Grande, Puerto Rico2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelton RW, Patel BC. Superomedial lid crease approach to the medial intraconal space: a new technique for access to the optic nerve and central space. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;17(4):241–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse DT, Nerad JA, Anderson RL, Corbett JJ. Optic nerve sheath fenestration in pseudotumor cerebri. A lateral orbitotomy approach. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106(10):1458–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersten RC, Kulwin DR. Optic nerve sheath fenestration through a lateral canthotomy incision. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111(6):870–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson SI. A surgical approach to plerocephalic disc oedema. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 1970;89:669–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wecker L On incision of the optic nerve in cases of neuroretinitis. Int Ophthalmol Cong Rep 1872;4:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbett JJ, Savino PJ, Thompson HS, et al. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Follow-up of 57 patients from five to 41 years and a profile of 14 patients with permanent severe visual loss. Arch Neurol 1982;39(8):461–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hupp SL, Glaser JS, Frazier-Byrne S. Optic nerve sheath decompression. Review of 17 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 1987;105(3):386–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbett JJ, Nerad JA, Tse DT, Anderson RL. Results of optic nerve sheath fenestration for pseudotumor cerebri. The lateral orbitotomy approach. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106(10):1391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keltner JL. Optic nerve sheath decompression. How does it work? Has its time come? Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106(10):1365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sergott RC, Savino PJ, Bosley TM. Modified optic nerve sheath decompression provides long-term visual improvement for pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106(10):1384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sergott RC, Savino PJ, Bosley TM. Optic nerve sheath decompression: a clinical review and proposed pathophysiologic mechanism. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1990;18(4):365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spoor TC, McHenry JG. Long-term effectiveness of optic nerve sheath decompression for pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111(5):632–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banta JT, Farris BK. Pseudotumor cerebri and optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology 2000;107(10):1907–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pineles SL, Volpe NJ. Long-Term Results of Optic Nerve Sheath Fenestration for Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: Earlier Intervention Favours Improved Outcomes. Neuroophthalmology 2013;37(1):12–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spoor TC, McHenry JG. Complications of optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology 1993;100(10):1432–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayreh SS. Pathogenesis of optic disc edema in raised intracranial pressure. Prog Retin Eye Res 2016;50:108–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H, Zhang Q, Tan S, et al. Update on the application of optic nerve sheath fenestration. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2017;35(3):275–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wall M Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin 2010;28(3):593–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreau A, Lao KC, Farris BK. Optic nerve sheath decompression: a surgical technique with minimal operative complications. J Neuroophthalmol 2014;34(1):34–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrity JA. What is the Current Status of Optic Nerve Sheath Fenestration? J Neuroophthalmol 2016;36(3):231–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson S The surgical relief of papilledema In: JS C, ed. The Optic Nerve. London, England: Henry Kimpton, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson S A surgical approach to plerocephalic disc oedema. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 1970;89:669–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker MS, Thurtell MJ, Allen RC. Support for the Egress Mechanism of Optic Nerve Sheath Fenestration. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;32(3):e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skalka HW. Ultrasonographic demonstration of patency of subarachnoid-orbital shunt. J Clin Ultrasound 1976;4(3):219–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seiff SR, Shah L. A model for the mechanism of optic nerve sheath fenestration. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108(9):1326–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keltner JL, Albert DM, Lubow M, et al. Optic nerve decompression. A clinical pathologic study. Arch Ophthalmol 1977;95(1):97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamed LM, Tse DT, Glaser JS, et al. Neuroimaging of the optic nerve after fenestration for management of pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110(5):636–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sallomi D, Taylor H, Hibbert J, et al. The MRI appearance of the optic nerve sheath following fenestration for benign intracranial hypertension. Eur Radiol 1998;8(7):1193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alsuhaibani AH, Carter KD, Nerad JA, Lee AG. Effect of optic nerve sheath fenestration on papilledema of the operated and the contralateral nonoperated eyes in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology 2011;118(2):412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brazis PW. Clinical review: the surgical treatment of idiopathic pseudotumour cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension). Cephalalgia 2008;28(12):1361–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spitze A, Malik A, Al-Zubidi N, et al. Optic nerve sheath fenestration vs cerebrospinal diversion procedures: what is the preferred surgical procedure for the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension failing maximum medical therapy? J Neuroophthalmol 2013;33(2):183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thuente DD, Buckley EG. Pediatric optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology 2005;112(4):724–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spoor TC, Ramocki JM, Madion MP, Wilkinson MJ. Treatment of pseudotumor cerebri by primary and secondary optic nerve sheath decompression. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112(2):177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]