Abstract

Objective:

To extend prior research on barriers to use of prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) by examining psychosocial correlates of intended use among physicians and pharmacists.

Methods:

Overall, 1,904 California physicians and pharmacists responded to a representative, statewide survey (24.1% response rate) from August 2016 to January 2017. Participants completed an online survey examining attitudes toward prescription drug misuse and abuse, prescribing practices, PDMP design and ease of use, professional obligations, and normative beliefs regarding PDMP use.

Results.

Perceived PDMP usefulness and normative beliefs fully mediated the relationship between concern and intentions; however, clinicians’ professional and moral obligation to use the PDMP was unrelated to intention to use the PDMP despite a positive relationship with concern about misuse and abuse. Compared to physicians, pharmacists reported greater concern about prescription drug misuse, greater professional and moral obligation to use PDMP, and greater rating of PDMP usefulness.

Policy Implications.

Interventions that target normative beliefs surrounding PDMP use and how to use PDMPs effectively are likely to be more effective than those that target professional obligations or moralize to the medical community.

The misuse and abuse of prescription drugs is a major ongoing threat to public health in the U.S. National surveys of drug use indicate that 6.4 million Americans age 12 and older used prescription drugs for non-medical purposes in 2015; approximately 60% of these drugs were opioid pain relievers.1 Increased supply and access to controlled substances is an important contributor to the increased prevalence of prescription drug misuse. Dramatic increases in opioid pain reliever prescriptions since 2000 have been observed despite relatively modest to no corresponding change in the population prevalence of chronic pain.2 Moreover, there is evidence that increased prescribing of opioid pain relievers has contributed to increases in the prevalence of opioid use disorder and opioid-related overdoses.3 Drug overdoses now represent the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S., with almost half involving opioid pain relievers.4

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMP) have been identified as a key tool for addressing the misuse and abuse of controlled substances. PDMPs are statewide databases that track outpatient controlled substances dispensed by pharmacies and that prescribers and pharmacists can query in real time to inform prescribing and dispensing decisions at the point of care. The CDC, the American Pharmacy Association, and the American Medical Association have all encouraged prescribers and pharmacists to use PDMPs regularly.5,6,7 The rationale for PDMP use has historically focused on the deterrence of “doctor shopping” or “pharmacy shopping”.8 Increasingly, PDMPs have been promoted as a clinical tool for the monitoring and management of opioid prescriptions and for mitigating the risk of addiction or overdose in patients receiving opioids for pain. For example, PDMPs allow clinicians to identify whether patients are currently receiving high-dose opioids. PDMPs also allow users to examine whether patients have been prescribed other high-risk medications (e.g., benzodiazepines) by other clinicians when making treatment decisions or deciding whether to dispense a controlled substance. In response to the opioid epidemic, a number of states have begun to mandate prescriber and pharmacist use of PDMPs.9

For PDMPs to be effective, clinicians must use them consistently. For example, Green and colleagues found that fewer than 50% of prescribers responding to a multi-state survey reported using the PDMP monthly.8 System design, practice constraints, and physician attitudes and experience may underlie inconsistent use of state PDMPs. Commonly reported barriers to use identified in prior survey research include login difficulty, system complexity, and lack of integration with electronic health records.10 Physicians’ attitudes also appear to be mixed regarding PDMPs. Some physicians perceive PDMPs as difficult to use or unhelpful, whereas others report PDMP use increases prescribing comfort and usefulness when making prescribing decisions.10,11 Prior studies have consistently documented system-related barriers to PDMP use10; however, solutions to these system-related problems must be state-specific because PDMPs are designed and implemented at the state level and so vary greatly across states. In contrast, little is known about how practice norms, clinician attitudes, and other psychosocial factors affect PDMP use. The effects of psychosocial factors on PDMP use are more likely to generalize across states due to the influence of national clinician organizations and guidelines. In addition, clinician attitudes around PDMP use have likely shifted substantially in recent years due to dramatic shifts in clinical guidelines away from opioid prescribing5, increased public awareness of opioid abuse and overdose as a public health crisis, and increased state-level mandates for PDMP registration and use. Thus, up-to-date research on psychosocial correlates of PDMP use is needed to inform public health and clinical policy related to PDMPs.

The present study addresses these needs by investigating psychosocial correlates of PDMP use among a representative sample of California physicians and pharmacists using constructs from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB).12 The TPB provides a widely used theoretical model to understand individual behavior change.13 Specifically, TBP predicts that behavior is influenced by attitudes (e.g., evaluation of PDMP usefulness), normative beliefs (e.g., PDMP use as customary among clinicians), and control beliefs (e.g., knowledge of how to use PDMPs). Few studies have examined PDMP use as a function of TPB constructs, and these have largely focused on pharmacists.14,15 Therefore we included several TPB constructs including attitudes toward the PDMP and PDMP normative beliefs as predictors of intent to utilize California’s PDMP. We also examine professional and moral obligations as an additional predictor of intention. Perceived obligations capture an individual’s internal sense of responsibility to carry out an action and have been demonstrated to predict intentions.16,17 The inclusion of professional and moral obligations may be particularly relevant among physicians given the standards of care that operate within the medical profession.18 Similar to prior research, we expect professional and moral obligations to be positively related to intentions to use California’s PDMP. Perceived barriers to PDMP use were also included to control for elements of system design that may influence use irrespective of physician and pharmacist beliefs.

Finally, clinician concern about prescription drug misuse and abuse in their community may be indicative of clinician readiness to undertake behaviors to reduce the issue. Greater concern regarding prescription drug misuse and abuse has been linked to changes in prescribing and dispensing practices and greater PDMP use for both physicians and pharmacists.19,20 Therefore we expected the relationship between concerns about misuse and abuse and PDMP use to be positive and partially mediated by TPB constructs (i.e. concern about misuse and abuse → PDMP specific beliefs → intent to use PDMP). In addition, evidence suggests that pharmacists and physicians may differ in their level of concern about misuse and abuse.19 Given prescribers and pharmacists unique role in patients’ access to prescriptions and use of California’s PDMP, which is likely reflected in their beliefs regarding PDMP usage, we believe mediation may be moderated by clinician type.

Methods

The survey was part of a larger state-based effort to examine PDMP use, barriers, and awareness and use of advanced PDMP functionality in California. California implemented mandatory PDMP registration for physicians and pharmacists on July 1, 2016. The study population was a quasi-random sample of one-twenty-fourth of all California pharmacists (n = 1,626) and allopathic physicians (n = 5,701), and one-twelfth of all California osteopathic physicians (n = 577) with licenses expiring in November and December of 2016, respectively. Initial survey invitations were mailed between August and October of 2016 from the clinicians’ respective regulatory board along with license renewal paperwork and one or two additional reminders were sent by mail or email. Surveys closed on January 31, 2017. All surveys were completed on the web; licensees were required to enter their license number before starting the survey to insure only sampled licensed clinicians responded. All surveys opened with two questions assessing licensees’ concern about prescription drug misuse and abuse. Physicians without a DEA license were screened out after these two questions. We considered all patients who completed these two survey questions as responders for purposes of calculating overall survey response rate. We compared demographic and specialty information (obtained from the regulatory boards) for responders versus non-responders in order to assess the extent to which results may be biased. A detailed description of the survey methods is available in Appendix A. The project was reviewed by the UC Davis institutional review board and deemed to be program evaluation rather than human subjects research.

Measures

The present study focuses on a subset of 23 items assessing concern about prescription drug misuse and abuse, beliefs about PDMP usefulness, barriers to PDMP use, beliefs about professional norms, social norms, and moral obligations to use the state’s PDMP. Questions for allopathic and osteopathic physicians were identical; questions for pharmacists were very similar to questions for physicians, but referred to dispensing rather than prescribing controlled substances. The survey was piloted among a group of community physicians and pharmacists who were not participants in the study. Scale items, descriptive measures, and reliability can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scales and associated items used in the present study.

| Physicians (n = 766 ) |

Pharmacists (n = 369 ) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale/Item | M | SD | αa | M | SD | αa |

| Concern about Misuse of Controlled Substances not concerned at all (0) to extremely concerned (3) | 0.85 | 0.82 | ||||

| How concerned are you about prescription drug misuse and abuse among patients in California? | 2.36 | 0.70 | 2.54 | 0.64 | ||

| How concerned are you about prescription drug misuse and abuse among patients in the community where you practice? | 2.19 | 0.80 | 2.39 | 0.77 | ||

| Usefulness of the PDMP; not useful at all (1) to very useful (4) | 0.91 | 0.90 | ||||

| How useful to you is CURES for helping manage patients with pain? | 2.34 | 1.10 | 2.73 | 0.95 | ||

| How useful to you is CURES for helping build trust with patients? | 2.16 | 1.04 | 2.60 | 1.01 | ||

| How useful to you is CURES for informing decisions to [prescribe/dispense] controlled substances? | 2.73 | 1.09 | 3.23 | 0.84 | ||

| How useful to you is CURES for identifying patients filling prescriptions from multiple doctors and/or pharmacies? | 3.16 | 1.06 | 3.46 | 0.83 | ||

| How useful to you is CURES for identifying patients who misuse or abuse controlled prescription drugs? | 3.08 | 1.04 | 3.40 | 0.85 | ||

| PDMP Normative Beliefs; 11-point scale, 0% to 100% | 0.80 | 0.74 | ||||

| What percentage of your colleagues do you think use CURES at least weekly? | 2.71 | 2.68 | 5.02 | 3.48 | ||

| What percentage of your colleagues do you feel ought to be using CURES at least weekly? | 4.85 | 3.66 | 6.16 | 3.79 | ||

| Professional and Moral Obligation; strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) | 0.89 | 0.84 | ||||

| I have a professional responsibility to check CURES when [prescribing/dispensing] controlled substances. | 3.52 | 1.10 | 4.15 | 0.88 | ||

| Checking CURES when [prescribing/dispensing] controlled substances is the right thing to do. | 3.74 | 1.01 | 4.19 | 0.86 | ||

| Using CURES when [prescribing/dispensing] controlled substances is considered standard of care. | 3.12 | 1.13 | 3.89 | 0.96 | ||

| [Prescribing/Dispensing] controlled substances without checking CURES would be morally wrong. | 2.44 | 1.06 | 2.99 | 1.12 | ||

| Checking CURES when [prescribing/dispensing] controlled substances is not a necessary part of my job. | 3.14 | 1.09 | 3.59 | 1.02 | ||

| Barriers to Use; strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) | 0.73 | 0.82 | ||||

| CURES is helpful. (RC) | 3.81 | 1.05 | 4.21 | 0.80 | ||

| CURES is not relevant to my practice. | 2.58 | 1.41 | 2.33 | 1.41 | ||

| CURES is easy to use. (RC) | 3.10 | 1.06 | 3.74 | 0.83 | ||

| I don't know how to use CURES. | 2.30 | 1.20 | 1.83 | 1.03 | ||

| CURES is checked by someone else in the office. | 2.06 | 1.13 | 2.22 | 1.20 | ||

| I have limited or no access to CURES while I practice. | 2.02 | 1.09 | 1.83 | 1.09 | ||

| How long have you been using CURES? | ||||||

| Less than 3 months (1), to more than 1 year (4) | 2.64 | 1.23 | 3.15 | 1.10 | ||

| How long have you been practicing in years? | 21.58 | 12.85 | 19.25 | 13.39 | ||

| How likely are you to use CURES at least once in the next 3 months?; extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (4) | 2.70 | 1.14 | 2.95 | 1.18 | ||

Note: Means and standard deviations are based on respondents with complete data at the item level; RC = Reverse coded item;

Cronbach’s alpha

Statistical Analysis

Primary statistical analysis was restricted to clinicians who were registered to the PDMP. First, we examined the bivariate correlations among the main study variables. We then used path analysis to estimate our mediation models for physicians and pharmacists. The models were stacked, which means the model fit was examined simultaneously for both clinician types. The model for each group tests the extent to which the association between concern regarding misuse and abuse of controlled substances and intention to use the state’s PDMP is mediated by PDMP specific attitudes and beliefs. We also modeled the mean structure in order to examine level differences between groups. We utilized full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to address missing data in the analysis.21 Analyses began with a fully constrained model, including means and variances of exogenous and endogenous variables. Parameter selection was based on theoretical considerations and an examination of modification indices and standardized residuals. Modification indices provide the expected change in model Chi-Square due to the inclusion of an unconstrained pathway. Decreases in model Chi-Square, RMSEA and AIC typically indicate better fit to the underlying observed data.22 A bias-corrected bootstrap procedure was used to examine the indirect relationship between concern about misuse and abuse of controlled substances and intent to use the state’s PDMP.23

Results

Our overall survey response rate was 24.1% (1,904 out of 7,894). A comparison of demographic characteristics suggests that physician responders were older (t6276 = 9.58, p < .001), more likely to be white (z = 6.72, p < .001) or Asian/Pacific Islander (z = 3.26, p < .001), and currently licensed (z = 9.75, p < .001) than non-responders. A greater proportion of the physician responders reported emergency medicine and psychiatry as specialties compared to non-responders, (z = 4.52, p < .001 and z = 4.39, p < .001, respectively). Similar to physicians, responding pharmacists were also likely to be older (t1614 = 5.53, p < .001) than non-responders. Responding pharmacists were also more likely to have a BS degree than PharmD compared to non-responders, (z = 4.58, p < .001 and z = 4.58, p < .001, respectively), though this is likely due to the age difference between responders and non-responders. A complete comparison of responders and non-responders can be found in Appendix B, eTable 1.

For physician responders, 91.3% reported not having a DEA license; 78.7% of physicians and 94.7% of pharmacists, respectively, reported not being registered with California’s PDMP. After excluding these responders, there were 988 registered physicians and 445 registered pharmacists for a total of 1,433 respondents available for analysis. Table 2 provides descriptive data on this sample retained for analysis by clinician type. Physicians were more likely to be white (57%) and male (59%). Among physician specialty groupings, the (38%) reported primary care as their specialty. Pharmacists were more likely to be Asian (45%) and female (53%). Only 6.6% and 2% of physicians and pharmacists identified as Hispanic or Latino, respectively. Pharmacists also tended to be younger (48 years old) on average than physicians (54 years old). In terms of dispensing sites, 37% of pharmacists reported working in a hospital or patient care setting, whereas 49% reported working in an independent, chain, or supermarket location.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample retained for analysis.

| Characteristic | Physicians | Pharmacists |

|---|---|---|

| N | 988 | 445 |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Male | 58.5 | 41.1 |

| Female | 33.2 | 52.8 |

| Other | 0.8 | 0.45 |

| Missing | 7.5 | 5.6 |

| Mean Age (n) | 53.6 (892) | 48.6 (413) |

| Mean Years in Practice (n) | 22.2 (906) | 20.2 (419) |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 56.5 | 38.2 |

| Black | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| American/Alaskan Native | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Asian | 21.9 | 44.5 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1.11 | 1.12 |

| Other | 6.6 | 6.5 |

| Missing | 11.3 | 7.2 |

| Hispanic or Latino (%) | ||

| Yes | 6.6 | 2.0 |

| No | 82.5 | 89.7 |

| Missing | 10.9 | 8.3 |

| Specialty (%) | ||

| Primary Care | 38.4 | |

| Surgical Specialty | 12.9 | |

| Psychiatry | 9.6 | |

| Emergency Medicine | 9.4 | |

| Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine | 6.3 | |

| Pediatrics | 6.2 | |

| Other | 8.6 | |

| Missing | 8.7 | |

| Dispensing Site (%) | ||

| Independent Pharmacy | 14.4 | |

| Chain Pharmacy | 29.7 | |

| Hospital | 24.5 | |

| Supermarket | 4.7 | |

| Mass Merchandiser | 0.7 | |

| Other patient care practice | 12.1 | |

| other non-patient care | 8.1 | |

| Missing | 5.8 |

PharmD became a requirement for pharmacists in 2003.

Correlations among Main Study Variables.

Bivariate associations among main study variables were qualitatively similar for physicians and pharmacists. There was a small, statistically significant positive association between concern about misuse and abuse of controlled substances and intention to use the PDMP among physicians and pharmacists. Similarly, moderate to strong statistically significant associations were found between intention to use the PDMP and usefulness, normative beliefs, and professional and moral obligations for both types of clinician. In contrast, barriers to use were negatively associated with all substantive variables except the number of years in practice for both groups. Appendix B, eTable 2 presents correlations for the main study variables by clinician type.

Path Model

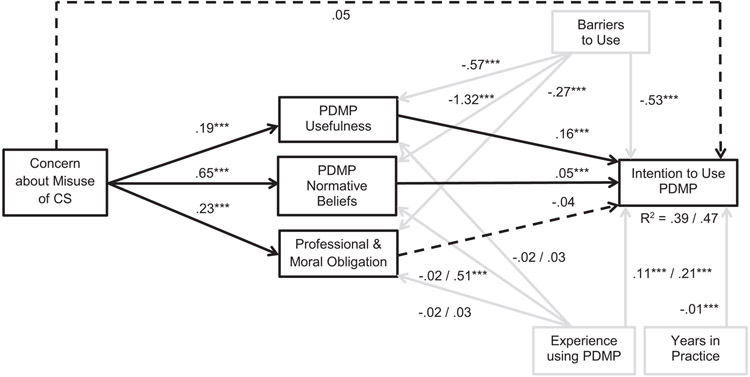

Figure 1 presents the final model with path coefficients for the physician and pharmacist groups, respectively. Covariances among exogenous variables and mediators were omitted for clarity. The final model provided optimal fit to the data despite a statistically significant Chi-Square goodness-of-fit test, X2 (31, n = 1,433) = 47.41, p = .03, RMSEA = .03, AIC = 36,869.62, CFI = .99. The lack of fit detected by the Chi-Square goodness-of-fit test is likely due to our large sample size. Appendix B, eTable 3 contains the sequential modeling fitting procedure and associated fit statistics.

Figure 1.

Final mediational model of the relationship between concern about prescription drug misuse and abuse and intention to use the California’s PDMP.

Parameters represent unstandardized coefficients; presence of multiple path coefficients represents physicians and pharmacists, respectively. Covariance among exogenous variables and mediators were omitted for clarity. CS = controlled substances. Solid black lines indicate statistically significant paths and dashed black lines indicate non-significant paths among substantive pathways. Solid gray lines indicate paths for control variables.

*** p <.001

Examination of the mean structure revealed several statistically significant differences between physicians and pharmacists (Table 2). Generally, pharmacists reported greater concern about misuse and abuse of controlled substances, PDMP usefulness, and professional and moral obligation to use the PDMP. For example, 68.7% of registered pharmacists agreed or strongly agreed that checking PDMPs when dispensing controlled substances was considered standard of care, whereas 36.6% of registered physicians agreed or strongly agreed that checking PDMPs when prescribing controlled substances was considered standard of care. Physicians reported greater perceived barriers to using the PDMP and greater intention to use the PDMP. Effect size estimates (i.e. Cohen’s D) suggest that differences between physicians and pharmacists were the largest for perceived PDMP usefulness and professional and moral obligations. There was no observed difference in PDMP-specific normative beliefs between clinician groups.

Differences in pathways among the main study variables for physicians and pharmacists were not statistically significant. Greater concern about misuse and abuse of controlled substances was related to 1) greater perceived usefulness of the PDMP, 2) greater perception of PDMP use as normative among colleagues, and 3) increased perception of a professional and moral obligation to the use the PDMP. Standardized coefficients suggest the relationship between concern and professional and moral obligation was slightly stronger (Bphysicians = .17 and Bpharmacists =.19) than the relationship between concern and PDMP usefulness (Bphysicians =.14 and Bpharmacists =.16), or concern and normative beliefs (Bphysicians = .16 and Bpharmacists =.13). The relationship between professional and moral obligation and intent to use the PDMP was not statistically significant. Standardized coefficients suggest that both PDMP usefulness (Bphysicians = .13 and Bpharmacists = .10) and subjective norms (Bphysicians = .13 and Bpharmacists =.14) were similarly related to intent to use the PDMP. As hypothesized, the direct pathway from concern about misuse and intent to use the state’s PDMP was not statistically significant, which suggests the relationship between concern about misuse and abuse was fully mediated by PDMP usefulness and normative beliefs. The model accounted for 39% and 47% of the variation in intent to use the state’s PDMP for physicians and pharmacists, respectively.

Indirect Effects of Concern

Statistically significant indirect effects were observed between concern about misuse and abuse of controlled substances and intent to use the state’s PDMP. As hypothesized, in both clinician groups a significant positive indirect effect between concern about misuse and abuse and intent to use the PDMP via PDMP usefulness and normative beliefs was observed, ab = 0.03, 95% CI [.02, .04] and ab = 0.03, 95% CI [.02, .05], respectively. Contrary to our expectations, professional and moral obligations was not a statistically significant mediator, ab = −0.01, 95% CI [−.02, 0.002]. In terms of the proportion of the indirect effect accounted for by each mediator, each appeared to contribute equally (approximately, 50%).

Discussion

The goal of the present study is to expand our understanding of physician and pharmacist use of PDMPs. We hypothesized that concern about prescription drug misuse would be positively associated with intention to use the state’s PDMP, and that this relationship would be partially mediated by perceived PDMP usefulness, normative beliefs, and professional and moral obligations to use the PDMP. We also expected the mediated relationship may be moderated by clinician type, although we had no specific prediction regarding how they may differ. Results provide partial support for our primary hypotheses. Perceived PDMP usefulness and normative beliefs fully mediated the relationship between concern and intentions; however, clinicians’ professional and moral obligation to use the PDMP was unrelated to intention to use the PDMP despite a positive relationship with concern about misuse and abuse. Although we found no evidence of moderated mediation between physicians and pharmacists, we did find that compared to physicians, pharmacists reported greater concern about prescription drug misuse, greater professional and moral obligation to use PDMP, and greater rating of PDMP usefulness.

The results partially support prior research focused on pharmacists. Two studies found that pharmacists’ positive attitudes toward the PDMP and subjective norms regarding use are positively associated with intentions to use PDMPs.14,15 Our work replicates these findings in a statewide sample and extends this pattern of relationships to physicians. Physicians and pharmacists who find the PDMP easy to use, helpful, and relevant are more likely to use the PDMP themselves. Moreover, normative use among their peers was predictive of intentions to use the state’s PDMP in both groups. In contrast, our findings did not support prior research suggesting professional and moral obligation is predictive of intention to use the PDMP among a convenience samples of pharmacists.14,15 There may be several reasons for the inconsistent results. First, our results may reflect a shift in attitudes over time, perhaps in response to policy and regulatory changes regarding PDMP use. Second, professional and moral obligations capture an individual’s internal sense of responsibility to carry out an action. The five-item scale we utilized consisted of multiple items designed to assess professional and moral obligations as standards, job duties, responsibilities, and what is perceived to be behaviorally right and wrong. Together, these items may better assess the internalized aspect of obligations rather than external obligations brought about by regulations.17 Finally, our use of a quasi-random sample may have avoided over-representing committed PDMP users.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of our approach was the use of a quasi-random sample of physicians and pharmacists. We provide evidence that our responders closely resemble our initial sample population, which improves our ability to generalize to the population of physicians and pharmacists licensed and registered to use California’s PDMP. In addition, the present study is the first to examine a behavioral model of PDMP use for both physicians and pharmacists, both of which play key roles in the availability of controlled substances. The findings are limited by the cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to infer a causal relationship among the factors examined. However, the associations examined are grounded in a well-established theory of behavior change. As states continue to mandate registration and use of PDMPs, future work detailing the conditions and factors related to consistent and appropriate use of PDMPs is warranted.

Public Health Implications

In the context of California, the present study demonstrates that even in the current prescription opioid overdose epidemic, enacting mandatory PDMP registration alone may not be sufficient to increase PDMP use if clinicians’ normative beliefs about PDMP use remain unchanged. The present findings may offer insight into how concerns regarding controlled substance misuse and abuse may translate into behavior change among physicians and pharmacists. Concern may be indicative of a general readiness to act on the perceived problem. In turn, physicians and pharmacists may have begun to consider the perceived usefulness of PDMPs and whether using such tools to address the issue is normative among their peer groups.

Research does suggest that PDMPs may be effective at reducing prescription drug misuse and abuse. Multiple evaluations have suggested that the implementation of state PDMPs has been followed by decreases in patient doctor shopping25 and opioid-related overdoses26. Effectiveness of efforts to educate physicians and pharmacists on the benefits of using PDMPs may depend, in part, on clinicians’ beliefs about their peers’ PDMP use. Public health officials, regulatory boards, and policy makers can use these results to help identify public health campaigns most likely to increase PDMP use. Based on our results, interventions that target normative beliefs surround PDMP use and how to use PDMPs effectively are likely to be more effective than those that target professional obligations or moralize to the medical community. For example, public health campaigns might consider sharing usage data, and increasing the use of peer-to-peer messages or clinician-led academic detailing.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Model-based means, difference tests, and effect sizes for physicians and pharmacists.

| Physicians |

Pharmacists |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | X2 | p |

Cohen's d |

| Concern about Misuse of Controlled Substances | 2.25 | 0.02 | 2.46 | 0.03 | 26.14 | < .001 | −0.29 |

| PDMP Usefulness | 3.32 | 0.12 | 3.87 | 0.14 | 28.33 | < .001 | −0.80 |

| Normative Beliefs | 4.48 | 0.45 | 5.10 | 0.60 | 1.90 | 0.18 | −0.23 |

| Professional & Moral Obligation | 3.31 | 0.14 | 3.90 | 0.16 | 25.24 | < .001 | −0.74 |

| Barriers to Use | 2.46 | 0.03 | 2.13 | 0.04 | 49.07 | < .001 | 0.40 |

| PDMP Experience | 2.52 | 0.04 | 3.08 | 0.06 | 67.80 | < .001 | −0.47 |

| Years in Practice | 22.29 | 0.44 | 20.29 | 0.64 | 6.60 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| Intention to Use PDMP | 3.28 | 0.21 | 2.83 | 0.25 | 10.6 | 0.001 | 0.51 |

Note: All tests had one degree of freedom; Standard deviations were calculated from model based variance estimates.

Appendix A

Survey Development

The survey was developed and conducted by University of California Davis and the California Department of Public Health, with cooperation from the California Board of Pharmacy, Medical Board of California (MBC), and Osteopathic Medical Board of California (OMBC). In addition to the items used in the study, the survey also assessed the following: prescribing / dispensing practice patterns, PDMP registration status, barriers to PDMP registration and use, and questions about specific features of CURES 2.0 (Controlled substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System; California’s PDMP), need for additional training, and comparison of CURES 1.0 versus CURES 2.0. In order to reduce respondent fatigue, skip logic was used so that, to the extent possible, prescribers only answered questions relevant to their practice. For example, physicians who reported not having a DEA license (and so are not required to register for CURES) did not answer questions about CURES; physicians who reported not prescribing any controlled substances or not being registered for CURES did not answer questions about how often they checked CURES or about ease of using CURES, respectively. An open-ended response question asking “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about CURES? (e.g., problems, recommendations)” was also included. The survey was a web-based survey hosted by the Qualtrics survey program (Provo, UT). The full survey is available from the corresponding author. Survey questions were reviewed by the study team and approved by the three regulatory boards.

Sampling Strategy

Our study population was drawn from all pharmacists and allopathic physicians with licenses expiring on November 30, 2016 and all osteopathic physicians with licenses expiring on December 31, 2016. Licenses in California must be renewed every 2 years and expire at the end of the licensee’s birth month; for osteopathic physicians, licenses must be renewed every 2 years and expire 6 times a year based on licensee birth month. Initial survey invitations were mailed from each regulatory board and were included in the same envelope as the licensee’s license renewal paperwork. One or two additional reminders were sent by mail from the survey team; an additional reminder letter was mailed from each regulatory boards return address. Allopathic physicians also received several email reminders (the OMBC and Board of Pharmacy do not maintain licensee email addresses and so could not send out email reminders). All survey materials included the logos of both UC Davis and the applicable regulatory board. Licensees were advised that participation was voluntary and that their individual responses would not be shared with the regulatory boards. All surveys were completed on the web; respondents could access the survey by typing in a short web address, scanning a QR code on their cell phone, or clicking on a survey link on the appropriate regulatory board’s web page. As previously mentioned, licensees were required to type in their license number before starting the survey; this prevented people from taking the survey multiple times, restricted respondents to licensees in our sample, and allowed us to keep track of respondents and in order to avoid sending reminders to licensees who had already completed the survey.

Appendix B

eTable 1.

Comparison of responder and non-responder characteristics.

| Physicians |

Pharmacists* |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responders (n = 1,406) |

Non- Responders (n = 4,872) |

p | Responders (n = 497) |

Non- Responders (n = 1119) |

p | ||||||

| Gender (n, %)^ | Gender (n, %) | ||||||||||

| Male | 908 | 64.6% | 3152 | 64.7% | 0.94 | Male | 207 | 41.7% | 439 | 39.2% | 0.34 |

| Female | 498 | 35.4% | 1719 | 35.3% | 0.92 | Female | 290 | 58.4% | 680 | 60.8% | 0.36 |

| Mean Age, Years (SD) ^^ | 56.7 | (13.0) | 52.7 | (14.1) | <.01 | Mean Age, Years (SD) | 48.9 | (13.6) | 44.8 | (13.8) | <.01 |

| Race / Ethnicity (n, %)^^^ | Degree type (n, %) | ||||||||||

| White | 672 | 47.8% | 1843 | 37.8% | <.01 | PharmD | 332 | 66.8% | 868 | 77.6% | <.01 |

| Black | 40 | 2.8% | 126 | 2.6% | 0.59 | BS** | 165 | 33.2% | 251 | 22.4% | <.01 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 389 | 27.7% | 1571 | 32.2% | <.01 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 40 | 2.8% | 226 | 4.6% | <.01 | Pharmacy School (n, %) | |||||

| Other | 16 | 1.1% | 26 | 0.5% | 0.01 | Foreign school | 61 | 12.3% | 89 | 8.0% | 0.01 |

| Decline to state | 198 | 14.1% | 764 | 15.7% | 0.14 | US school | 436 | 87.7% | 1030 | 92.1% | <.01 |

| Missing | 51 | 3.6% | 316 | 6.5% | <.01 | California school | 251 | 50.5% | 644 | 57.6% | 0.01 |

| Primary Specialty (n, %)# | |||||||||||

| Internal Medicine | 186 | 13.2% | 589 | 12.1% | 0.25 | ||||||

| Family Medicine | 175 | 12.4% | 503 | 10.3% | 0.02 | ||||||

| Psychiatry | 116 | 8.3% | 250 | 5.1% | <.01 | ||||||

| Emergency Medicine | 93 | 6.6% | 185 | 3.8% | <.01 | ||||||

| Anesthesiology | 78 | 5.5% | 228 | 4.7% | 0.18 | ||||||

| OBGYN | 55 | 3.9% | 207 | 4.2% | 0.58 | ||||||

| Pediatrics | 84 | 6.0% | 295 | 6.1% | 0.91 | ||||||

| Pain medicine | 10 | 0.7% | 23 | 0.5% | 0.27 | ||||||

| Radiology | 53 | 3.8% | 241 | 4.9% | 0.07 | ||||||

| Current License | 1390 | 98.9% | 4450 | 91.3% | <.01 | ||||||

Note: Bolded p-values are less than Bonferroni corrected threshold of .0016

1 missing for gender;

weighted average;

Licensees can check multiple ethnicities

Percentages due not sum to 100%; Licensees may list more than one specialty.

Data missing for 10 pharmacists;

PharmD became the entry-level degree in 2003

eTable 2.

Correlation among the main study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Concern about Misuse of CS | - | .31*** | .19*** | .27*** | −.19*** | .07 | .09** | .11** |

| 2. PDMP Usefulness | .27*** | - | .38*** | .41*** | −.57*** | .30*** | −.04 | .38*** |

| 3. Subjective Norms | .27*** | .51*** | - | .36*** | −.45*** | .36*** | −.05 | .41*** |

| 4. Professional & Moral Obligation | .22*** | .40*** | .46*** | - | −.31*** | .13*** | −.05 | .20*** |

| 5. Barriers to Use | .25*** | .61*** | −.46*** | −.30*** | - | −.53*** | .15*** | −.60*** |

| 6. PDMP Experience | .17*** | .33*** | .30*** | .15*** | −.38*** | - | −.13*** | .49*** |

| 7. Years in Practice | −.05 | .14*** | −.10*** | −.03 | .16*** | −.16*** | - | −.23*** |

| 8. Intention to Use PDMP | .23*** | .50*** | .41*** | .23*** | −.58*** | .37*** | −.21*** | - |

Notes: Physicians are represented in the lower diagonal; Pharmacists in the upper diagonal

Tests of statistical significance based on bootstrapped standard errors; CS = Controlled substances

p < .01

p < .001

eTable 3.

Model fit statistics and nested model tests for mediational model.

| Model | X2 | df | p | RMSEA | AIC | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hypothesized model | 337.60 | 47 | < .001 | .09 | 37241.81 | .89 |

| 2. Free equality constraints on means | 137.14 | 39 | < .001 | .06 | 37057.34 | .96 |

| 3. Free paths from experience using PDMP to endogenous variables | 114.91 | 35 | < .001 | .06 | 36937.12 | .97 |

| 4. Free covariance between experience using PDMP and barriers | 98.92 | 34 | < .001 | .05 | 36921.13 | .97 |

| 5. Free variance of mediators | 47.41 | 31 | .03 | .03 | .99 | |

| Model Difference Tests | ΔX2 | Δdf | p | |||

| 1 vs 2 | 200.46 | 8 | < .001 | |||

| 2 vs 3 | 22.23 | 4 | < .001 | |||

| 3 vs 4 | 15.99 | 1 | < .001 | |||

| 4 vs 5 | 51.51 | 3 | < .001 | |||

Contributor Information

John Pugliese, Safe and Active Communities Branch California Department of Public Health Sacramento, California.

Garen Wintemute, Department of Emergency Medicine University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, California.

Stephen G. Henry, Division of General Medicine, Geriatrics, and Bioethics University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, California.

References

- 1.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H-50) 2016. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician 2010; 13:401–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Overdoses of Prescription Opioid Pain Relievers --- United States, 1999—2008. MMWR 2011; 60:1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR 2016; 65:1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA 2016; 315:1624–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Medical Association. AMA Offers Vision for Ending Opioid Epidemic at National Summit March 29, 2016; https://www.ama-assn.org/content/ama-details-vision-ending-opioid-epidemic-national-rx-drug-abuse-and-heroin-summit

- 7.American Pharmacy Association. Draft CDC Opioid Prescribing Guideline for Chronic Pain January 13, 2016; http://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/20160113%20-%20American%20Pharmacists%20Association%20-%20CDC%20Opioid%20Prescribing%20Guideline%20Comments%20-%20Final.pdf

- 8.Green TC, Mann MR, Bowman SE, et al. How does use of a prescription monitoring program change medical practice? Pain Med 2012; 13:1314–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Mandated use of state prescription drug monitoring programs (PMPS): Highlights of key state requirements. January 1, 2017; http://www.namsdl.org/library/6735895A-CA6C-1D6B-B8064211764D65D0/.

- 10.Blum CJ, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. A survey of Physicians’ Perspectives on the New York State Mandatory Prescription Monitoring Program (ISTOP). J Subst Abuse Treat 2016; 70:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin DH, Lucas E, Murimi IB, Jackson K, Baier M, Frattaroli S, et al. 2017. Physician attitudes and experiences with Maryland’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). Addiction. Feb; 112(2):311–319. doi: 10.1111/add.13620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishbein M, Ajzen I Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviors with the Theory of Planned Behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 2011; 5(2):97–144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavaza P, Fleming M, Barner JC. Examination of psychosocial predictors of Virginia pharmacists’ intention to utilize a prescription drug monitoring program using the theory of planned behavior. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014; 10(2):448–58. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming ML, Barner JC, Brown CM, Shepherd MD, Strassels S, Novak S. Using the theory of planned behavior to examine pharmacists’ intention to utilize a prescription drug monitoring program database. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014; 10(2):285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajzen I The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991; 50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorsuch RL, Ortberg J. Moral obligation and attitudes: their relation to behavioral intentions. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983; 44:1025. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randall DM, Gibson AM. Ethical decision making in the medical profession: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Bus Ethics 1991; 10: 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright RE, Reed N, Carnes N, Kooreman HE. Concern about the Expanding Prescription Drug Epidemic: A Survey of Licensed Prescribers and Dispensers. Pain Physician 2016; 19:E197–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norwood CW, Wright ER. Promoting consistent use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP) in outpatient pharmacies: Removing administrative barriers and increasing awareness of Rx drug abuse. Res Social Adm Pharm 2016; 12:509–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enders CK. A Primer on Maximum Likelihood Algorithms Available for Use With Missing Data. Struct Equ Modeling 2001; 8:128–141. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0801_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu L, & Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999; 6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RJA, Schenker N. Missing Data. In: Arminger G, Clogg CC, Sobel ME, ed. Handbook of Statistical Modeling for the Social and Behavioral Sciences New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1995:39–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.PDMP Center of Excellence, Brandeis University. Briefing on PDMP Effectiveness 2014. http://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/COE documents/Add to TTAC/Briefing%20on%20PDM P%20Effectiveness%203rd%20revision.pdf

- 26.Patrick SW, Fry CE, Jones FJ, Buntin MB. Implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs associated with reductions in opioid-related death rates. Health Aff 2016; 35:1324–1332. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.