Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is membrane-enveloped and an initial infection step is joining/fusion of viral and cell membranes. This step is catalyzed by gp41 which is a single-pass integral viral membrane protein. The protein contains a ~170-residue ectodomain located outside the virus that is important for fusion, and includes the fusion peptide (FP), N-helix, loop, C-helix, and viral membrane-proximal external region (MPER). The virion initially has non-covalent complexes between three gp41 ectodomains and three gp120 proteins. A gp120 contains ~500-residues and functions to identify target T-cells and macrophages via binding to specific protein receptors of the target cell membrane. Gp120 moves away from the gp41 ectodomain, and the ectodomain is thought to bind to the target cell membrane and mediate membrane fusion. The secondary and tertiary structures of the ectodomain are different in the initial complex with gp120 and the final state without gp120. There is not yet imaging of gp41 during fusion, so the temporal relationship between the gp41 and membrane structures is not known. The present study describes biophysical and functional characterization of large gp41 constructs that include the ectodomain and transmembrane domain (TM). Significant fusion is observed of both neutral and anionic vesicles at neutral pH which reflects the expected conditions of HIV/cell fusion. Fusion is enhanced by the FP, which in HIV/cell fusion likely contacts the host membrane, and the MPER and TM, which respectively interfacially contact and traverse the HIV membrane. Initial contact with vesicles is made by protein trimers which are in a native oligomeric state that reflects the initial complex with gp120, and also is commonly observed for the ectodomain without gp120. Circular dichroism data support helical structure for the N-helix, C-helix, and MPER, and non-helical structure for the FP and loop. Distributions of monomer, trimer, and hexamer states are observed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), with dependences on solubilizing detergent and construct. These SEC and other data are integrated into a refined working model of HIV/cell fusion that includes dissociation of the ectodomain into gp41 monomers followed by folding into hairpins that appose the two membranes, and subsequent fusion catalysis by trimers and hexamers of hairpins. The monomer and oligomer gp41 states may therefore satisfy dual requirements for HIV entry of membrane apposition and fusion.

Summary

The present study reports vesicle fusion at physiologic pH by a hyperthermostable HIV gp41 hairpin trimer that includes the FP and TM segments. This final gp41 state may catalyze HIV/cell fusion steps that follow apposition of the membranes, where the latter step is likely concurrent with hairpin formation. In addition, the present and earlier studies report partial dissociation of the hairpin trimer into monomers. The monomers may be evolutionarily advantageous because they aid initial hairpin formation, and they may also be the target of gp41 N- and C-helix peptide fusion inhibitors.

For Table of Contents

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is enveloped by a membrane obtained during budding from an infected host cell. Infection of a new cell begins with joining (fusion) of membranes of the virus and host cell, and this process is catalyzed by the ~41 kDa glycoprotein “gp41” which is single-pass integral viral membrane protein.1, 2 Gp41 also contains a ~170-residue ectodomain and ~150-residue endodomain that are respectively located outside and inside the virus (Fig. 1A). Gp41 is synthesized as the second subunit of a larger gp160 precursor protein, and following proteolytic cleavage, the first subunit gp120 forms a non-covalent complex with the gp41 ectodomain, and contains three gp41 and three gp120 molecules. We use the residue numbering scheme for gp41 based on the gp160 precursor, so that the N-terminus of gp41 is residue 512. Host cells are identified by HIV via gp120 binding to primary CD4 and secondary CXCR4 and CCR5 receptors, followed by separation of gp120 from gp41 and a structural rearrangement of the gp41 ectodomain. Mutagenesis-fusion relationships for gp160-mediated cell-cell fusion support a primary role for the gp41 ectodomain in fusion.3, 4 There are structures of the initial complex of the gp41 ectodomain with gp120, with typical resolution of 3–5 Å, 5–10 and high-resolution structures of soluble regions of the gp41 ectodomain without gp120.11–14 For the initial complex with gp120, the gp41 ectodomain exhibits a set of distinct α helices connected by loops. The central α7 helix (gp41572–595) forms an interior parallel trimeric bundle with N-terminal end pointing towards gp120 and C-terminal end likely pointing towards the viral membrane. A loop from the α7 N-terminus connects to the α6 helix (gp41530–543) and then N-terminal fusion peptide (FP) domain (gp41512–529), with extended structure for the FP. The FP is exposed and an epitope of neutralizing antibodies.15, 16 A loop from the α7 C-terminus connects to the α8 helix (gp41619–623) and then α9 helix (gp41628–664). The α6, α8, and α9 helices are outside and approximately perpendicular to the α7 bundle, and are also on three sides of the bundle. Comparison of this initial gp41 ectodomain structure in complex with gp120 to the later gp41 structure without gp120 shows large-scale extensions and topological rearrangements of helical segments. The latter structure is a “trimerof-hairpins” with three N-helices (gp41536–596) that form an interior bundle, followed by loops, and then C-helices (gp41616–675) that run antiparallel in the exterior grooves of the bundle.11–14 The hairpin is probably the final structure during fusion based on a Tm ≈ 110 oC.17, 18 The color-coding in Fig. 1A reflects the N- and C- helices of the ectodomain structure without gp120.

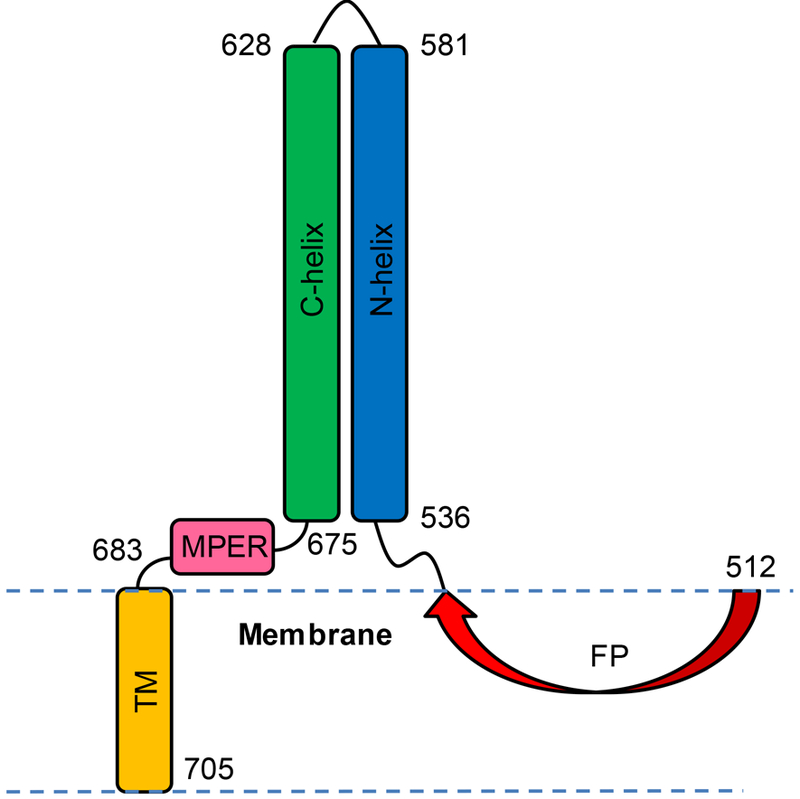

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic diagrams of full-length HIV gp41 and the four truncated constructs of the present study with domains and corresponding colors: FP ≡ fusion peptide, red; N-helix, blue; loop, grey; C-helix, green; MPER ≡ membrane-proximal external-region, pink; TM ≡ transmembrane domain, orange; and endo = endodomain, white. The four constructs have non-native SGGRGG replacing native residues 582–627. (B) Amino acid sequences with colors matching segments in panel A and the non-native C-terminal G6LEH6 or G8LEH6 in black. The H6 is for Co2+-affinity chromatography and the G6LE/G8LE are necessary spacers for exposure of the H6 tag. The sequence is from the HXB2 laboratory strain of HIV.

Membrane structures during fusion have also been characterized by electron and fluorescence microscopies and include: (1) “hemifusion” in which a single bilayer diaphragm maintains separation of the HIV and host cell contents; (2) “pore formation” of channels in the diaphragm that permit diffusion of <1 kDa species; and (3) “pore expansion” in which the pores irreversibly coalesce to break the diaphragm and permit complete mixing of the viral and cell contents.2, 19 There has not yet been imaging of the gp41 ectodomain during fusion, so there is only limited knowledge of the temporal relationship between the membrane states and gp41 structural states during fusion, and therefore only limited knowledge about which fusion step(s) are catalyzed by which gp41 structure(s). Current fusion mechanistic models are often based on the observation that individual gp41 N- and C-helix peptides inhibit pore formation but not pore expansion.19 Such peptides would likely not tightly bind to a final-stage trimer-of-hairpins structure but could bind to a variety of other gp41 structures, which supports the hypothesis that the peptides bind to earlier-stage gp41 structures and prevent formation of the final structure.20 Electron microscopy from the 1980’s onward has shown that HIV can enter cells via direct fusion with the plasma membrane or via endocytosis followed by fusion with the endocytic membrane.1, 21 The HIV-containing endosomes likely remain at neutral pH, which contrasts with endocytic entry by other enveloped viruses, e.g. influenza, for which reduction of endosomal pH triggers conformational changes in the viral fusion protein and subsequent fusion of the viral and endocytic membranes.22 Some of the most recent data support direct fusion of HIV and plasma membranes as the primary route of HIV infection.23

The present study compares different gp41 constructs in the absence of gp120 and provides data on their structures, oligomeric states, and catalysis of vesicle fusion. The present and earlier data are combined to create an integrated model of gp41-mediated membrane fusion. Fig. 1A displays gp160-based residue numbering of gp41 with color-coding of different domains with defined structures and/or functions. The “fusion peptide” (FP) includes 16 apolar residues at the gp41 N-terminus and the name reflects impairment of gp160-mediated fusion when there are deletions/mutations in the FP.3, 24 The “N-helix” and “C-helix” regions are each ~60-residue continuous helices in the final-state six-helix bundle structure adopted by the gp41 ectodomain in the absence of gp120.12–14 As discussed above, shorter helical regions with a different tertiary structure are formed in the initial ectodomain complex with gp120. The membrane-proximal external region (MPER) is proposed to interfacially bind the viral membrane and is adjacent to the transmembrane (TM) region.25, 26 Although the MPER is commonly defined as gp41662–683, gp41662–675 is structurally the C-terminal end of the C-helix in large ectodomain constructs.13 The structural distinction between MPER and TM regions is also unclear, as fairly continuous helical structure is adopted by peptides corresponding to gp41671–693, gp41683–704, and gp41677–716.27, 28

Models of gp160-mediated fusion usually show movement of gp120 away from gp41 after receptor binding to gp120, followed by conformational change of the freed gp41 and then binding of the gp41 FP in the target membrane.29 These steps all occur prior to membrane fusion. The fusion relevance of gp41 without gp120 is also supported by common observation of fusion of vesicles after addition of gp41 constructs to the vesicle solution.30 Gp41 constructs catalyze fusion for a variety of lipid compositions that often include phosphatidylcholine, as well as other lipids such as cholesterol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylglycerol, and sphingomyelin.30–32 There are increased rates and extents of vesicle fusion when the FP and MPER are included in the N-helix/loop/C-helix construct.29

Gp41-only constructs with longer N- and C-helices are typically only soluble at pH < 4 and visibly aggregate at physiologic pH, so most biophysical work has been done at low pH. Atomic-resolution structures of N-helix/loop/C-helix constructs with [protein] > 2 mM show trimers of hairpins with an interior bundle of three parallel N-helices, and three C-helices packed in the exterior grooves of the bundle and antiparallel to the N-helix direction.11, 12 Analytical ultracentifugation (AUC) sedimentation equilibrium data have been interpreted to support Ka ≈ 1012 M–2 for the 3 monomer ↔ 1 trimer equilibrium, which corresponds to equal trimer and monomer masses when [total protein] ≈ 1 μM.33, 34The equilibrium has also been observed in elution peaks of size exclusion chromatography (SEC), but the data are consistent with Ka ≈ 108 M–2, with equal monomer and trimer masses when [total protein] ≈ 60 μM.29, 35 We don’t understand the discrepancy of AUC vs. SEC. Dodecylphosphocholine detergent reduces Ka, i.e. favors monomer vs. trimer.36–39 Hairpin structure for the monomer similar to that in the trimer is supported by negligible dependence of circular dichroism (CD) and NMR signals on protein concentration, as well as retention of hyperthermostable Tm > 100 oC.18, 40 Monomers are appealing in fusion mechanistic models because after gp120 moves away from gp41, asynchronous conformational changes of individual gp41 monomers into hairpins is topologically easier than concerted changes of a trimer.29, 36, 41 Monomers may also be a binding target of gp41 N- and C-helix peptides that have been shown to be effective at fusion inhibition up to the final pore expansion step.19

Detergent-associated peptides with sequences corresponding to FP, MPER, and TM sequences are typically monomers with α helical structure.27, 42–44 Membrane-associated FP often forms small oligomers with intermolecular antiparallel β sheet structure.31, 45 Peptides corresponding to FP or MPER sequences often catalyze vesicle fusion, and fusion is increased when FP or MPER is appended to a hairpin construct with N-helix/loop/C-helix sequence.25, 29, 31 One caveat is that significant fusion with these constructs required pH ≤ 4 and anionic vesicles.46 Fusion by hairpin constructs therefore correlated with electrostatic attraction between highly cationic protein (charge ≈ +10) and anionic vesicles. There is likely much less attraction for HIV/cell fusion at physiologic pH because the ectodomain is approximately neutral. One important result of the present study is significant fusion at physiologic pH by hairpin constructs that contain the FP, MPER, and TM regions. There are similar results with neutral and anionic vesicles, which supports a major contribution to fusion from hydrophobic rather than electrostatic protein/membrane interaction, and is similar to HIV/cell fusion.

Materials and methods

Materials

Materials were purchased from the following companies: DNA – GenScript, Piscataway, NJ; Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) strain – Novagen, Gibbstown, NJ; Luria-Bertani (LB) medium – Dot Scientific, Burton, MI; isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) – Goldbio, St. Louis, MO; Cobalt affinity resin – Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA; 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (sodium salt) (POPG) – Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL. Most other materials were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

Protein sequences

Fig 1 displays schematic diagrams and amino acid sequences of the four gp41 constructs of the present study. The sequences are from the HXB2 laboratory strain of HIV and have the gp160 precursor residue numbering, 1–511 and 512–856, respectively, for the gp120 and gp41 subunits. Fig. S1 displays the corresponding DNA sequences. In the absence of gp120, the gp41 soluble ectodomain (SE) adopts thermostable hairpin structure, i.e. N-helix/180o-turn/C-helix, with approximate respective residues 536–596/597–615/616–675.12, 13 Our constructs have residues 582–627 replaced with the six-residue non-native SGGRGG, and SE and FP+SE constructs with this replacement still adopt highly-helical and thermostable SE structure.47 The four constructs of the present study are: (1) HM (“hairpin” + MPER), a SE construct – gp41535–581/SGGRGG/628–683; (2) FP_HM, a FP+SE construct – gp41512–581/SGGRGG/628–683; (3) HM_TM, a SE+TM construct – gp41535–581/SGGRGG/628–705; and (4) FP_HM_TM, a FP+SE+TM construct – gp41512–581/SGGRGG/628–705. All constructs have a non-native H6 affinity tag at their C-terminus that is preceded by a G6LE or G8LE spacer. The spacer is needed for exposure of the affinity tag during purification. HM and HM_TM have a M535C mutation, which is needed for native chemical ligation with FP which is not part of the present study.

Protein expression

Each DNA insert was subcloned into a pET-24a(+) vector that contained the Lac operon and kanamycin antibiotic resistance. The plasmid was transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain. Typical bacterial culture conditions included use of: (1) LB medium that contained 50 mg kanamycin/L to select for bacterial cells that contained the plasmid; and (2) 180 rpm shaking at 37 oC. Bacterial stocks were prepared by mixing equal (0.5 mL) volumes of overnight culture and 50% v/v glycerol, followed by freezing and storage at –80 °C. New cultures were prepared with overnight growth of 50 μL bacterial glycerol stock in 50 mL medium, followed by addition of 1L fresh medium and 2-hour growth until OD600 ≈ 0.8. Protein expression was induced at 37 oC for 5 hours with addition of 2 mmole isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside.

Separation of cellular fraction enriched in inclusion bodies

Subsequent purification of recombinant protein (RP) was mostly done at 4 oC. First, the cell pellet was harvested by centrifugation (9000g, 10 min) with subsequent storage at −20 oC. Wet cells (5 g) were lysed by tip sonication in 40 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4. Initial separation of RP from other cellular components was based on most RP being in inclusion bodies, which are both insoluble in PBS and pelletable by modest centrifugation (48000g, 20 min). The supernatant contains soluble proteins and other molecules, as well as suspended membrane fragments which are only effectively pelleted by >200000g. A solid that is highly-enriched in RP inclusion bodies was therefore obtained by initial modest centrifugation, and then 2× repetition of re-suspension in 40 mL fresh PBS and modest centrifugation.

13C NMR of inclusion body fraction

The relative expression quantity of each RP construct was assessed using 50 mL expression in medium with 1-13C Gly, followed by separation of the cell fraction enriched in inclusion bodies, and 13C NMR of this fraction.48 The RP is synthesized mostly during the expression period, so RP quantity correlates with labeled Gly incorporation and 13C NMR signal intensity. Cells were grown overnight in 50 mL LB medium and then transferred to 50 mL minimal medium containing 250 μL of 50% glycerol, and 10 mg each of 1-13C glycine and the 19 other unlabeled amino acids. These unlabeled amino acids inhibit amino-acid biosynthesis and therefore metabolic scrambling of the 1-13C Gly. After two-hours of additional growth, expression was induced for five hours, followed by sonication in PBS and centrifugation. This pellet was lyophilized and a ~50 μL aliquot was then transferred to a magic-angle-spinning (MAS) NMR rotor with 4 mm diameter. A 13C NMR spectrum was then acquired using an instrument with 9.4 T magnet and Agilent Infinity Plus console. The pulse sequence was 1H→13C cross-polarization followed by 13C acquisition with 1H decoupling, and a spectrum was the sum of ~11000 scans.

Protein purification

The pellet enriched in inclusion bodies was completely solubilized by tip sonication in 40 mL of PBS at pH 7.4 that also contained 8M urea, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.8% sodium lauroyl sarcosinate (Sarkosyl). Co2+ resin (1 mL) was added and the resin + solution was agitated for 2 hours at ambient temperature to bind RP to resin. Solution containing unbound protein was removed by gravity filtration of the suspension.

At this point, separate protocols were used to obtain RP soluble in either SDS or in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC). The first step in the SDS protocol was further removal of unbound protein with 3× resin washes with 1 mL aliquots of the PBS/urea/SDS/Sarkosyl solution, and subsequent gravity filtration. Bound protein was eluted from the resin by 0.5 mL aliquots (4×) of the PBS/urea/SDS/Sarkosyl solution with 250 mM imidazole, and gravity filtration. The eluent fractions were pooled and then mixed with an equal volume of buffer that contained 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 0.17% n-Decyl-β-D-Maltoside, 2 mM EDTA, and 1 M L-arginine, with subsequent agitation overnight at 4 °C.49 Arginine, urea, and other detergents were removed by dialysis against 10 mM Tris at pH 7.4 with 0.2% SDS. If the intermediate mixing step with the arginine solution was skipped, RP precipitated during dialysis, which suggests that RP aggregates are broken up by the arginine solution.

The above procedure was attempted using DPC rather than SDS in the dialysis buffer, but RP consistently precipitated, presumably because aggregation associated with loss of urea and arginine occurred faster than solubilization by DPC. We therefore tried buffer exchange with RP still bound to the column.41 Exchange was accomplished by 3× suspension of the resin in 1 mL of 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 that also contained 0.25% DPC, with subsequent gravity filtration. RP was then eluted in the pH 7.4 phosphate buffer with 0.25% DPC and 250 mM imidazole. The eluent fractions were pooled and imidazole removed by dialysis against pH 7.4 phosphate buffer with 0.25% DPC, or by dialysis against 20 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 3.2 with 0.25% DPC. Purified RP concentrations were determined using A280.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD spectra at ambient temperature were acquired with a Chirascan instrument (Applied Photophysics) equipped with a quartz cuvette with 1 mm pathlength, and 190 – 260 nm wavelength range scanned in 0.5 nm steps. The [RP] ≈ 10 μM and each spectrum was the (protein + buffer) – (buffer) difference. For some samples, a temperature-series of CD spectra were acquired in 5 oC increments over a 25–90 oC range. These latter spectra were acquired using a J-810 instrument (Jasco) and a water circulation bath. There was no visible precipitation at any temperature, or after cool-down, which evidences retention of soluble RP.

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

RP solution was first dialyzed against the SEC running buffer and then concentrated to ~1 mg RP/mL, with subsequent separation of particulates using centrifugation at 9000g for 10 minutes. There was no visible precipitate for samples in SDS and a very small precipitate for samples in DPC. A ~100 μL aliquot was injected into a DuoFlow Pathfinder 20 instrument (Bio-Rad) equipped with a Tricorn Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Technologies). Instrument parameters included flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, A280 detection, and ~10-fold dilution in the column, i.e. ~0.1 mg RP/mL.

Protein-induced vesicle fusion

Fusion activities of the different gp41 constructs were assayed by protein-induced lipid mixing between unilamellar vesicles. Assays were done for vesicles with two different lipid compositions: (1) 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1’-rac-glycerol) (POPG), and cholesterol (Chol) with 8:2:5 mole ratio; and (2) POPC:Chol with 2:1 mole ratio. The Chol mole fraction in both compositions is close to that of the plasma membrane of cells infected by HIV.50 Compositions (1) and (2) have respective net negative and neutral charges, so comparison between them allows assessment of the impact of protein/vesicle electrostatics on fusion. HIV gp41 likely makes initial contact with the outer leaflet of the cell membrane that normally has little anionic lipid, but recent data support scramblase-mediated transport of anionic phosphatidylserine lipid from the inner- to the outer-leaflet prior to gp160-mediated fusion.51 Vesicle preparation began with dissolution of POPC, POPG and Chol (1.6, 0.4, and 1.0 μmole) or POPC and Chol (2.0 and 1.0 μmole) in 1 mL chloroform, followed by solvent removal using dry nitrogen gas and then overnight vacuum. The dry lipid films were then suspended in 2 mL aqueous buffer and subjected to 10 freeze/thaw cycles to create unilamellar vesicles. Subsequent extrusion (10×) of the suspension through a polycarbonate membrane with 100 nm diameter pores resulted in vesicles with typical diameters of 200–300 nm, as observed by electron microscopy.52 For each composition, a set of companion “labeled” vesicles were also prepared that contained additional 2 mole% fluorescent lipid N-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) phosphatidylethanolamine and 2 mole% quenching lipid N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) phosphatidylethanolamine. Systematic differences among vesicle compositions were minimized by weighing all lipids at the same time using the same scale and lipid loss was estimated to be ~30% during extrusion. The final vesicle solution contained [POPC+POPG+Chol] ≈ 225 μM and (labeled vesicles):(unlabeled vesicles) = 1:9. The solution was transferred to a quartz cuvette in a fluorimeter and subjected to constant stirring at 37 oC. Fluorescence was monitored using 467 nm excitation, 530 nm detection, and 1 s time increment. The initial baseline fluorescence F0 was determined, and an aliquot of protein stock solution was then added (t = 0). The stock solution contained [protein] = 40 μM in 10 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.4 with 150 mM NaCl and 0.2% SDS. The time-dependent fluorescence increase ΔF(t) = F(t) – F0 was diagnostic of protein-mediated fusion between a labeled and unlabeled vesicle. Relative to the initial labeled vesicle, the fused vesicle has higher fluorescence because of longer average fluorophore-quencher distance. The dead-time after protein addition was ~5 s and final asymptotic fluorescence change was usually achieved by t = 600 s. A 12 μL aliquot of 10% Triton X-100 was then added to solubilize the vesicles, with corresponding maximum fluorescence change (ΔFmax). The percent fusion parameter was calculated as [ΔF(t)/ΔFmax] × 100. Assignment of protein as the cause of fusion is supported by negligible fusion after addition of an aliquot of stock solution without protein.

Results

Protein expression, solubilization, and purification

After expression, the first step in RP purification was cell lysis in PBS. SDS-PAGE of the soluble lysate of each of the constructs did not show any obvious band corresponding to RP, which evidenced low RP solubility in PBS, as would be expected for membrane proteins. The pellet size was visibly reduced by resuspension in PBS and centrifugation (2×), which is consistent with removal of non-RP material. Similar RP expression levels were evidenced by similar pellet sizes, and by similar 13CO NMR intensities of pellets obtained from expression in minimal medium with added 1-13C Gly (Fig. S2). We performed the inexpensive 13C labeling followed by separation of inclusion-body-enriched pellet and 13C NMR because this approach provides an accurate estimate of RP expression when most RP is in inclusion bodies.48 Less accurate results are obtained by the alternate method of solubilization of the pellet in SDS followed by SDS-PAGE. The RP band intensity in the gel generally decreases with protein hydrophobicity, which could be explained by incomplete solubilization of aggregates by SDS.

Our next task was to find other conditions that completely solubilized the RP-rich pellet. Solubilization was achieved by tip sonication of mixtures that contained PBS at pH 7.4 and either: (1) 8M Urea; (2) 6M GuHCl; (3) 8M Urea and 0.8% Sarkosyl; or (4) 8M Urea, 0.5% SDS, and 0.8% Sarkosyl. Solubilization after tip sonication was assessed both visually, and also by pellet size after centrifugation at 45000g for 20 minutes. Each solution was then subjected to Co2+-affinity chromatography, followed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S3). The darkest RP bands with highest purity were obtained for mixture (4) which was then used for all subsequent protein purification (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE of the purified HM (MW = 13.7 kDa), HM_TM (MW = 16.7 kDa), FP_HM (MW = 16.5 kDa), and FP_HM_TM (MW = 18.9 kDa).

All constructs have a non-native C-terminal H6 affinity tag preceded by either a G6LE or G8LE spacer, where the spacer is required for RP binding to the Co2+ resin. The SE by itself likely still adopts helical hairpin structure in high concentrations of denaturant, so we expect that the spacer affords greater solvent exposure of the H6 tag.29 The longer G8LE spacer was required for FP_HM_TM binding to the resin.

Our next task was to find conditions without urea and Sarkosyl for which solubility was retained for all purified RP’s. Dialysis was done against a variety of buffers, and soluble RP’s were obtained for 10 mM Tris at pH 7.4 and 0.2% SDS. We were also interested in studying the RP’s in DPC detergent because it has the phosphatidylcholine headgroup common to a significant fraction of lipid in membranes of cells infected by HIV.50 Although the RP’s precipitated if dialyzed directly against lowor neutral- pH buffers containing 0.25% DPC, all RP’s were soluble if the initial exchange into buffer with 0.25% DPC was done with RP bound to Co2+-resin, followed by elution using buffer with DPC and 250 mM imidazole, and then dialysis to remove the imidazole.41 The final solutions contained 0.25% DPC and either 20 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 3.2 or 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4. RP solubility when initial exchange was done with resin-bound RP vs. RP precipitation when initial exchange was done by dialysis of a RP solution suggests that RP aggregates can form quickly, but are not the lowest free-energy state in 0.25% DPC.

Fig. 2 displays SDS-PAGE of the four RP’s after dialysis into 10 mM Tris at pH 7.4 with 0.2% SDS. Bands corresponding to FP_HM, HM_TM, and FP_HM_TM were cut from a gel and subjected to trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry. Peptides were identified from each of the three bands that provided 80, 55, and 75% sequence coverage, respectively (Fig. S4). Anti-H6 Western blots also supported protein identities (data not shown). The migration rate of HM-TM in the gel is slower than FP-HM even though the two proteins have similar MW’s. The migration rate of a protein in SDS-PAGE is inversely correlated with the mass-bound SDS, and this mass is likely greater for TM than for FP because of the greater hydrophobicity of the TM segment.53 This interpretation is supported by SEC of the proteins in SDS in Fig. 6A and accompanying analysis in Table 2.

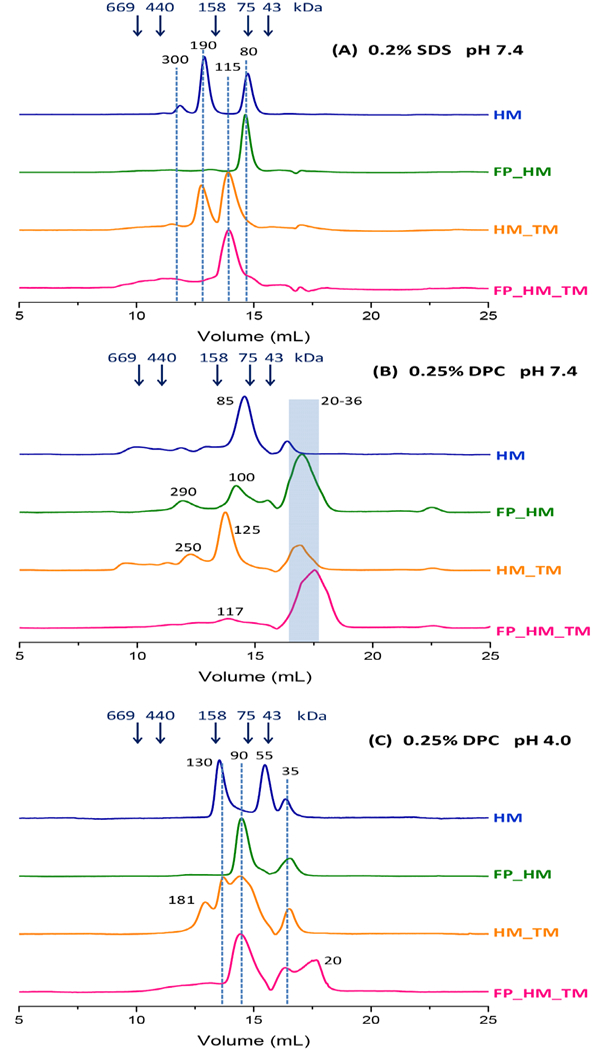

Figure 6.

SEC of gp41 constructs under the following conditions: (A) 10 mM Tris at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% SDS, and ambient temperature; (B) 20 mM phosphate at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.25% DPC at 4 °C; and (C) 20 mM acetate at pH 4.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.25% DPC at 4 °C. SEC was obtained with a Superdex 200-increase column, 1 mg/mL protein loading with ~10-fold dilution in the column, and A280 detection. The arrows in the plots are at the elution volumes of the MW standards, and some of the peaks are identified with dashed lines and with MW’s calculated from interpolation between MW standards.

Table 2.

SEC peak interpretation a

| Condition | Construct(s) | MWpeak | Oligomer | MWprotein | MWdetergent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS, pH 7.4 | HM, FP_HM | 80 | trimer | 45 | 35 |

| HM_TM, FP_HM_TM | 115 | trimer | 55 | 60 | |

| HM, HM_TM | 190 | hexamer | 100 | 90 | |

| DPC, pH 7.4 | HM, FP_HM, HM_TM FP_HM_TM |

35 | monomer | 15 | 20 |

| HM, FP_HM, HM_TM, FP_HM_TM |

100 | trimer | 50 | 50 | |

| DPC, pH 4.0 | HM, FP_HM, HM_TM FP_HM_TM |

35 | monomer | 15 | 20 |

| HM | 55 | trimer | 40 | 15 | |

| FP_HM, HM_TM FP_HM_TM |

90 | trimer | 50 | 40 | |

| HM, HM_TM | 130 | hexamer | 100 | 30 | |

| HM_TM | 180 | hexamer | 100 | 80 |

Peaks are grouped by oligomer assignments, and MWpeak and MWprotein are typical values for the assignment.

Typical purified yields of HM, FP_HM, HM_TM, and FP_HM_TM were respectively ~10, 0.5, 0.5, and 0.3 mg/L bacterial culture. The higher yield for HM may be due in part to ~2× higher expression (Fig. S2), and may also have a contribution from better binding to the Co2+-resin. Although there were not obvious RP bands in washes of resin prior to elution, resin binding of FP_HM_TM required a longer glycine spacer than the other constructs. This suggests occlusion of the H6 tag by FP and TM segments, which is sterically plausible because of SE helical hairpin folding even with denaturant at high concentration.29 The lower FP_HM_TM yield was not due to incomplete elution from the Co2+-resin. The resin was magenta color before protein binding and changed to pale pink after protein binding. After protein elution, the resin changed back to the original magenta color. The resin was then boiled, and SDS-PAGE of the boiled solution did not show a band at the MWFP_HM_TM.

Influence of FP and TM on hyperthermal α helical hairpin structure

Fig. 3 displays CD spectra at ambient temperature of the four gp41 constructs in: (A) 0.2% SDS at pH 7.4; (B) 0.25% DPC at pH 7.4; and (C) 0.25% DPC at pH 4.0. We tried to obtain the most quantitative comparison between constructs by acquiring all spectra for a single buffer during the same day. All spectra have the characteristic shape of α helical secondary structure with minima near 208 and 222 nm. This helicity is consistent with the helical hairpin structure of gp41 SE. The |θ| values for a single construct in DPC are similar at low and neutral pH, which supports a pH-independent hairpin structure. The average θ222-DPC/θ222-SDS ≈ 3/2, with variation of this ratio among constructs. This ratio suggests higher helicity in DPC vs. SDS. The shapes of the CD curves are typically different in DPC vs. SDS, as reflected by typical θ208-DPC ≈ θ222-DPC, whereas θ208-SDS ≈ 1.2 × θ222-SDS.

Figure 3.

Circular dichroism spectra at ambient temperature of samples containing ~10 μM protein in different buffer + detergent solutions: (A) 10 mM Tris at pH 7.4 and 0.2% SDS; (B) 20 mM phosphate at pH 7.4 and 0.25% DPC; and (C) 20 mM acetate at pH 4.0 and 0.25% DPC. All spectra for a single buffer + detergent condition were acquired on the same day. The 0.20% SDS is ~5 × CMC and the 0.25% DPC is ~8 × CMC.

The HM_TM construct has the largest |θ| values in all three buffer conditions, with |θ222| ≈ 28,000 degrees cm2/dmole in DPC that correlates with 85% average helicity. This is equal to the average helicity calculated using a model of 100% helicity of 123/125 of the native residues and 0% helicity for 2 native residues as well as 20 non-native residues, i.e. SGGRGG loop and C-terminal G6LEH6 (Table 1). Nearly complete native helicity is consistent with a fully-folded protein containing SE helical hairpin and TM helix structural elements. Similar analysis of |θ222| of HM yields ~76% experimental helicity and ~10 non-helical native residues. These residues are most likely at the N- and C-termini of the hairpin, based on reasoning that the TM stabilizes hairpin helical structure. Addition of the FP segment decreases average helicity, and this correlates with similar loss of helicity deduced from comparative CD spectra of the shorter “HP” (gp41535–581/SGGRGG/628–666) and “FP_HP” (gp41512–581/SGGRGG/628–666) constructs.47 HP and HM share the same N-helix and SGGRGG non-native loop, but HP lacks the 17 native C-terminal residues of HM, as well as the non-native C-terminal G6LEH6. The average helicity of FP_HM and FP_HM_TM in DPC is ~73%, which corresponds to non-helical structure for ~20 (FP_HM) and ~24 (FP_HM_TM) native residues. Most of these residues are likely within the FP, which matches earlier CD data in DPC consistent with ~20-more non-helical residues for gp41512–705 vs. gp41538–705.34, 37 CD spectra in SDS at pH 7.4 were obtained in 5 oC increments between 25 and 90 oC. The temperature-series for a single construct were all acquired during the same day. Fig. 4 displays representative spectra at 25, 60, and 90 oC, and Fig. 5 displays plots of θ222 vs. temperature. The spectra in Fig. 4 and Fig. 3A were acquired on different instruments, but reproducibility is evidenced by similar shapes of ambient-temperature spectra, and by the same ordering of θ222 values with construct. Fig. 5 shows only moderate decreases in |θ222| with increasing temperature, which supports Tm ≥ 90 °C for the four constructs. Similar moderate CD changes have also been observed for the shorter HP and FP_HP constructs, and the combined data support hyperthermostable hairpin SE structure for all constructs.47

Table 1.

Analysis of CD spectra

Figure 4.

Circular dichroism in 0.2% SDS at pH 7.4 at 25, 60, and 90 oC. Differences between the ambient-temperature spectra of the same construct for these data vs. Fig. 3A may be partly due to use of different CD instruments.

Figure 5.

θ222 vs. temperature in 0.2% SDS at pH 7.4. All spectra for a single construct were acquired on the same day.

HM and FP_HM exhibit similar Δ(|θ222|) ≈ 4000 degrees cm2/dmole over the 25–90 oC range, which is consistent with assignment of the helical structure to the HM region. In some contrast, HM_TM exhibits Δ(|θ222|) ≈ 5000, and FP_HM_TM exhibits Δ(|θ222|) ≈ 3000 degrees cm2/dmole, so appending both the FP and TM domains appears to stabilize the helical hairpin structure of HM. This may be due to location of the FP and TM segments in the same micelle, so opening of the hairpin requires micelle deformation to maintain detergent contact with both FP and TM. There is not this penalty if the construct contains only the FP or the TM.

SEC supports co-existing protein monomers, trimers, hexamers, and higher-order oligomers

Fig. 6 displays SEC of the gp41 constructs in: (A) SDS at pH 7.4; (B) DPC at pH 7.4; or (C) DPC at pH 4.0. These detergents were chosen in part because all proteins are visually soluble in them and are also thermostable, as assessed by their CD spectra. The running [protein] ≈ 5 μM is comparable to the CD experiments. The 0.20% SDS is ~5 × CMC and the 0.25% DPC is ~8 × CMC. All buffers also contained 150 mM NaCl to inhibit protein adsorption to the column material. There is <10% statistical probability of protein occupation of a micelle, so oligomerization is likely due to protein/protein interaction rather than crowding. Reproducibility is evidenced by similar traces for replicate samples (Fig. S5A,B) and for samples with and without DTT reducing agent in the injection sample and running buffer (Fig. S5C).

SEC measures particle migration (elution) volumes, that reflect particle sizes and shapes, and an elution volume is converted to a particle MW using interpolation between the elution volumes of the soluble protein standards. One advantage of SEC is the reproducibility of the elution volume values for a single column-type across different chromatography instruments, and therefore different research studies. Table 2 lists our proposed assignments of many peaks in the SEC traces. Most assignments are protein monomer, trimer, or hexamer because these ectodomain species have been commonly observed in earlier studies using SEC, SEC-MALS, and AUC.29, 33–40 The peak SEC elution volumes in Fig. 6 reflect protein + detergent masses, so assignment of a peak to a particular protein oligomer correlates to an estimated detergent mass = total mass – protein mass. Assignment of peak to a specific oligomer is also based on having a reasonable value for the detergent mass contribution, which takes into account: (1) the typical 20–25 kDa mass of a detergent micelle without protein; (2) a ~5:1 mass ratio for SDS:hydrophobic protein segment; and (3) a SEC-MALS-based report of ~17 kDa DPC per monomer gp41 ectodomain segment.36, 53

The SEC traces in 0.2% SDS at pH 7.4 exhibit the smallest number and narrowest peaks. A dominant peak is observed for FP_HM at 80 kDa and for FP_HM_TM at 115 kDa. The 80 kDa peak is also observed for HM and the 115 kDa peak for HM_TM, and are accompanied by a peak of approximately equal intensity at 190 kDa for both constructs. The reproducibility of elution volumes among different constructs supports separation of discrete species.

The 78 kDa peak is proposed to include HM trimer (41 kDa) and SDS (37 kDa), and the 82 kDa peak includes FP_HM trimer (49 kDa) and SDS (33 kDa). The 115 kDa peak includes either HM_TM (50 kDa) or FP_HM_TM (57 kDa) trimer, and SDS (60 kDa). Relative to the 80 kDa peaks, the additional ~25 kDa SDS mass in the 115 kDa peaks is consistent with solvation of the TM segment by SDS. There is also correlation with the 15% SDS-PAGE in Fig. 2 that shows ~5 kDa increase in monomer MW with inclusion of TM vs. much smaller MW change for inclusion of FP. The ~60 kDa detergent mass for FP_HM_TM trimer matches the detergent mass determined by AUC for the influenza virus HA2 fusion protein trimer, where both proteins contain a FP domain and a TM domain.56 Hexamer assignment of the 190 kDa peak correlates with HM (80 kDa) or HM_TM (100 kDa), and SDS (100 kDa), and dodecamer assignment of the 300 kDa peak correlates with HM (160 kDa) and SDS (140 kDa).

SEC traces in DPC (Figs. 6B – pH 7.4, 6C – pH 4.0) exhibit some peaks with MW’s comparable to those in SDS, and assignment is done by similar reasoning. For example, HM at pH 7.4 has a dominant peak at 85 kDa that we assign to HM trimer (41 kDa) + DPC (44 kDa). Our trimer assignment correlates with previous sedimentation velocity AUC analysis of the related gp41528–579/SGGRGG/628–683 construct in DPC at pH 7.0.39 This construct includes the MPER, but lacks most of the FP and all the TM. The major species was a trimer (45 kDa) + DPC (23 kDa). Major trimer peaks in other SEC traces include the 125 kDa peak at pH 7.4 of HM_TM (50 kDa) + DPC (75 kDa); and the 90 kDa peaks of FP_HM, HM_TM, or FP_HM_TM (50 kDa), and DPC (40 kDa) at pH 4.0. Minor peaks assigned to trimers include the 100 kDa peak of FP_HM (50 kDa) + DPC (50 kDa) and the 115 kDa peak of FP_HM_TM (55 kDa) + DPC (60 kDa).

All DPC traces have peaks at lower MW’s that are assigned to monomer species. There is often a defined peak at 35 kDa with calculated monomer protein (15 kDa) + DPC (20 kDa) contributions, and sometimes a broader peak at lower MW’s. The monomer peaks are dominant for FP_HM and FP_HM_TM at pH 7.4. Our SEC monomer assignment correlates with earlier sedimentation velocity AUC data in DPC at pH 7 for several shorter constructs like gp41528–579/SGGRGG/628–655 and gp41546–579/SGGRGG/628–683.39 Sedimentation coefficients evidenced monomer protein (10 kDa) + DPC (15 kDa).

For constructs in DPC, there are high-MW peaks at pH 7.4 that are weak and broad, while there are defined peaks at pH 4.0 including 55 kDa for HM, 90 kDa for FP_HM, HM_TM, and FP_HM_TM, 130 kDa for HM and HM_TM, and 180 kDa for HM_TM. The 90 kDa peak is assigned to trimer protein (50 kDa) + DPC (40 kDa) and the 180 kDa peak to hexamer protein (100 kDa) and DPC (80 kDa), like similar MW peaks in SDS at pH 7.4. The 55 kDa peak, unique to HM, is tentatively-assigned to trimer protein (40 kDa) + non-micellar DPC (15 kDa). HM is less hydrophobic than the other proteins and the large ~+30 positive charge may enable solubility with less detergent. The 130 kDa peak is similarly assigned to hexamer protein (100 kDa) + DPC (30 kDa).

Hairpin protein-induced vesicle fusion at both physiologic and low pH

Fig. 7 shows the time-courses of vesicle fusion induced by the four different gp41 constructs for vesicles composed of either POPC:POPG:Chol (8:2:5) or POPC:Chol (2:1), at either pH 3.2 or pH 7.4. The displayed traces in Fig. 7 were carried out on the same day with the same protein stocks. Fig. 8 displays long-time (~600 s) fusion extents based on the Fig. 7 data. There was ±2% typical variation in long-time fusion extent for replicate assays that were carried out on different days with the same protein stocks and vesicle preparations.47 Assays done with different protein stocks and vesicle preparations exhibited larger systematic variations in absolute fusion extents, but retained similar trends in comparative extents with respect to construct, pH, and lipid composition (Fig. S6). POPC and Chol are included to represent some of the physicochemical characteristics of the plasma membrane of cells infected by HIV, including PC as a common lipid headgroup, and Chol as ~0.3 mole fraction of total lipid.50 POPG has a calculated charge of –1 at both pH’s, and is included to represent the ~0.15 mole fraction of anionic lipids.51

Figure 7.

Vesicle fusion assays of gp41 proteins. Fusion was initiated by addition of an aliquot of protein stock solution at 0 s, and subsequent fusion was monitored by increased fluorescence associated with inter-vesicle lipid mixing. The stock contained 40 μM protein in buffer at pH 7.4 with 0.2% SDS, and the protein + vesicle mixture contained [protein] = 0.5 μM, [POPC+POPG+Chol] = 225 μM, and vesicle molar compositions and pH’s: (A) POPC:Chol = 2:1 at pH 3.2; (B) POPC:POPG:Chol = 8:2:5 at pH 3.2; (C) POPC:Chol = 2:1 at pH 7.4; and (D) POPC:POPG:Chol = 8:2:5 at pH 7.4. Fusion was not observed for any vesicle composition after addition of an aliquot of buffer + 0.2% SDS without protein. All data were obtained on the same day with the same protein stocks. The assay dead time was ~5 s. Small negative-values of fusion in a few cases were due to decreased fluorescence associated with the volume increase from addition of the protein aliquot.

Figure 8.

Long-time fusion extents (after ~600 s) based on the Fig. 7 data with protein:total lipid mole ratio = 1:450. Replicate data were acquired on different days with the same protein stocks and vesicles, and exhibited ±2% typical variation in extents among assay replicates. Fig. S6 shows extents from experiments using different protein stocks and vesicle preparations, and also comparative fusion extents at protein:lipid ratios = 1:450 and 1:225.

Vesicle fusion was probed by inter-vesicle lipid mixing detected after addition of 40 μM protein solubilized in 10 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.4, with 0.2% SDS and 150 mM NaCl. No fusion was observed for buffer without protein, so fusion was due to protein/vesicle rather than SDS/vesicle interaction. Protein stocks in SDS at neutral pH were used because trimer is a dominant oligomeric state (Fig. 6A), which matches the likely initial and final gp41 ectodomain states during HIV/cell fusion.10, 12 Vesicle fusion was not done using protein stocks in DPC because of greater variation in oligomer states among constructs, with large monomer fraction in several cases (Fig. 6B,C). Earlier vesicle fusion studies were done with stock protein with large monomer fraction.29, 46 It is unlikely that fusion can be examined with a single oligomeric species, based on earlier work in which a second SEC was run on a fraction representing a single oligomeric state of an initial SEC.29 This second SEC was similar to the original SEC, and showed a mixture of oligomeric states that was consistent with thermodynamic equilibrium.

HIV/host cell fusion occurs at pH 7.4, and gp41-induced vesicle fusion was also detected at this pH (Figs. 7 C,D; Figs. 8 and S6). Most earlier studies were done with shorter constructs and showed that fusion required low pH and anionic vesicles.30, 46 These previous results were interpreted to support attractive electrostatics as a requirement for protein/vesicle binding. For the present study, HM did not induce fusion at neutral pH, which is consistent with these previous studies, but larger constructs induced appreciable fusion.29 FP_HM_TM exhibited the greatest fusion extent, while FP_HM and HM_TM had smaller extents that were similar to one another, with FP_HM consistently higher than HM_TM. These data support a positive correlation between protein hydrophobicity and vesicle fusion. Fusion was moderately-higher for anionic vs. neutral vesicles, which evidences that electrostatic repulsion between anionic vesicles does not affect fusion. These data are also consistent with little bulk electrostatic interaction between a vesicle and the nearly neutral protein, whose calculated charge is ~ –1 at pH 7.4.

The pH 3.2 data provide a comparison with earlier studies on shorter gp41 constructs at low pH. One common feature of all four conditions of Figs. 7 and 8 is highest fusion extent for FP_HM_TM, which supports the hydrophobicity/fusion correlation. Fusion extent at low pH was generally comparable or greater than at neutral pH. This correlates with different magnitudes of protein charge at low vs. neutral pH, ~ +10 vs. –1. Interestingly, the greater extent at low pH is likely not due to direct protein/vesicle attraction, because extent was also greater for neutral vs. anionic vesicles. This result contrasts with the reverse trend at neutral pH.

Discussion

This paper presents a systematic structural and functional comparison of protein constructs that contain folded domains of the gp41 protein. We integrate our data with existing data, and propose some new interpretations of these data. Key results include: (1) helical SE and TM, and non-helical FP in SDS and DPC detergents; (2) hyperthermostability with Tm > 90 oC; (3) trimer and sometimes hexamer protein in SDS at pH 7.4, and mixtures of monomer, trimer, and higher-order oligomer protein in DPC at pH 4.0 and 7.4; and (4) substantial protein-induced vesicle fusion, including fusion of neutral and anionic vesicles at neutral pH, which are the conditions similar to HIV/cell fusion. Vesicle fusion by a large gp41 construct has rarely been observed under these conditions, and is aided by inclusion of both the FP and TM, and by protein which is predominantly trimer rather than monomer.

Protein constructs

The constructs had a non-native 6-residue sequence that replaced the SE loop and adjoining terminal regions of the SE N- and C-helices (Fig. 1). This modified SE was chosen because of better solubility properties while retaining hyperthermostable helical structure with Tm > 100 oC (Figs. 3–5). All constructs could be dialyzed without precipitation into SDS solution at pH 7.4, which was supported by SEC traces with small peaks assigned to aggregates, and sharp peaks assigned either to trimer or hexamer protein (Fig. 6A and Table 2). Direct dialysis of FP_HM_TM into DPC solution resulted in rapid precipitation. There was not precipitation if DPC solution was introduced with protein bound to Co2+-resin, followed by elution. Our observation appears consistent with one previous study, but not others, and we do not understand the reason for this apparent discrepancy.34, 41 Relative to SDS, the SEC traces in DPC exhibit more peaks, with most intense ones assigned to monomer, trimer, and hexamer protein (Fig. 6B-C). Weaker peaks are due to larger species, but not assigned to specific oligomers. The general similarity between the SEC traces of different constructs in SDS at pH 7.4 is consistent with thermodynamic equilibrium, and there is similar consistency between traces of different constructs in DPC at both pH 7.4 and 4.0, which also evidences equilibrium. Precipitation upon direct dialysis into DPC thus appears to be due to a rapid rate of aggregation rather than thermodynamic stability of large aggregates.

Synthesis of oligomeric and structural data

We and other groups have worked on characterizing the structural and oligomeric states of gp41 constructs and we integrate our current data with earlier data. Common features of most studies are the very high helicity of the SE and Tm > 100 oC, particularly if the construct contains longer N- and C-helix segments with complementarity between their hydrophobic surfaces. These features are exhibited with native or non-native loop, for solutions without detergent at low pH, and for solutions with detergent at low and neutral pH.17, 18, 29, 34, 41, 47, 57 The CD data of the present work correlate with helical TM and with non-helical FP, where the latter result is consistent with an earlier CD study, but not consistent with earlier NMR chemical shifts.34, 47 The protein and detergent concentrations are ~50-fold lower in CD relative to NMR. In membrane, the FP often adopts intermolecular antiparallel β sheet structure.31, 45, 58 Our CD data at higher temperature support greater thermostability of FP_HM_TM vs. more truncated constructs. The same thermostability correlation was also observed for the influenza virus HA2 protein, whose sequence is non-homologous with gp41, but performs a similar fusion function.49 Close FP/TM contact has not been detected by NMR, so increased thermostability may be due to greater micelle deformation needed to surround both FP and TM for an unfolded SE.34

SEC peaks of the present study are interpreted to support gp41 with SE which is either monomer, trimer, hexamer, or larger oligomer. We compare to SEC data from earlier studies as well as equilibrium and sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) data. There is variability among SE lengths in these studies, and we initially consider longer constructs for which Tm > 100 oC, which matches the stability of full-length SE.17, 57 The typical [total protein] ≈ 5 μM for all these SEC and AUC studies, which makes it more reasonable to compare oligomeric interpretations.

Our SEC data support predominant trimer fraction for all four of our constructs in SDS at neutral pH, with some hexamer fraction for HM and HM_TM, and no monomer fraction for any construct. There is significant monomer fraction for all constructs in DPC at both low and neutral pH, as well as trimer and larger oligomer fractions. These data suggest that monomer charges are stabilized by the zwitterionic charges of DPC but not by anionic SDS. We had previously observed predominant monomer faction for the SE HP construct (gp41535–581/SGGRGG/628–666) at low pH without detergent, whereas large aggregates are predominant at neutral pH.29, 35 These different oligomeric states correlate with different magnitudes of calculated protein charge, ~ +10 at low pH vs. –1 at neutral pH, with corresponding large differences in inter-monomer electrostatic repulsion. We don’t observe greater monomer fraction in DPC at low vs. neutral pH which supports the significance of electrostatic interactions between the protein and the DPC headgroups with pH-independent zwitterionic charges.

Our SEC in DPC at low pH is generally consistent with an earlier study of the gp41512–705 construct in DPC at low pH.34 The previous SEC exhibited monomer:trimer ratio ≈ 3:1, which contrasts with sedimentation equilibrium AUC data that were interpreted to support monomer ↔ trimer Ka ≈ 1012 M–2 that would correspond to a monomer:trimer ratio ≈ 1:4. Our SEC of the closely-related FP_HM_TM (gp41512–581/SGGRGG/628–705) in DPC at low pH exhibits monomer:trimer ratio ≈ 1:1 which is intermediate between the two previous results. For the gp41538–705 SE+MPER+TM construct, and the gp41538–665 SE-only construct, sedimentation equilibrium data in DPC at low pH are interpreted to support Ka ≈ 1010 M–2.37 Combined consideration of all Ka’s suggests that FP and TM segments stabilize the trimer vs. monomer, even though they don’t directly interact. There is correlation with our observation that FP_HM_TM is the most thermostable of the four fully-trimeric constructs in SDS at neutral pH. For gp41538–665 at low pH without detergent, sedimentation equilibrium Ka’s of 5 × 1011 M–2 and 7 × 1012 M–2 have been independently reported, and likely reflect the magnitude of uncertainty for this technique.33, 37 The general consensus from the literature is that monomer is stabilized by low pH and also stabilized by DPC detergent.

Sedimentation velocity AUC has been applied to a construct very similar to FP_HM_TM in DPC.41 Although Ka’s were not reported from sedimentation velocity, the data exhibited a sedimentation coefficient that increased abruptly at pH 5, and was interpreted to support monomer below pH 5 and trimer above pH 5. We did not observe this behavior in SEC and do not understand the discrepancy between methods. The AUC result correlates with the reduction in calculated protein charge from +9 to +3 between pH 4 and 5.

The constructs of the present study were designed based on SE structures to have N- and C-helix segment lengths that yielded Tm > 100 oC, like the full-length protein. There are earlier studies on constructs with similar or shorter helix lengths, with some surprising and sometimes conflicting results about monomer vs. trimer fractions in DPC. For example, the longer gp41528–579/SGGRGG/628–683 construct at 400 μM concentration and low pH exhibits a tumbling time derived from NMR that is consistent with predominant monomer.38 This corresponds to Ka ≤ 106 M–2 which is 100× smaller than the Ka determined by sedimentation equilibrium AUC for the shorter gp41538–579/SGGRGG/628–665 construct.37 At neutral pH, a much larger Ka ≥ 4 × 1010 M–2 has been reported for the longer construct based on sedimentation velocity data, whereas much smaller Ka ≤ 2 × 108 M–2 were reported for either gp41546–579/SGGRGG/628–683 or gp41528–579/SGGRGG/628–655, which are constructs with respectively a shorter N- or C-helix.39

FP_HM_TM structural model

Fig. 9 displays a medium-resolution structural model for FP_HM_TM which incorporates the Table 1 analysis of the CD spectra as well as previous results. This model likely reflects the final hairpin gp41 state during fusion, based on Tm > 90 oC (Fig. 5). There aren’t yet clear experimental data that follow the temporal relationship between gp41 structure and membrane structure during membrane fusion, but efficacies of peptide inhibitors added at different stages of membrane fusion are reasonably interpreted to support existence of the hairpin state of gp41 at intermediate stages of membrane fusion.19, 29 A monomer is displayed for clarity but the model should also be valid for a trimer bundle or a hexamer (dimer of trimer bundles). The HM SE region is primarily hairpin structure that contains helices over residues 536–581 and 628–675. This structure is supported by very high helicity of HM and HM_TM, and by a previous crystal structure.13 The C-terminal MPER and TM regions are also highly helical, based on the HM_TM CD spectrum, and on structures in detergent of peptides corresponding to MPER and/or TM sequences.27, 44 There are likely breaks in helical structure, based on the topological constraints of the probable membrane interface and traversal locations for the MPER and TM domains, respectively.

Figure 9.

Structural model of FP_HM_TM based on circular dichroism spectra of the four constructs, and other data. A monomer is shown for clarity but the model should be valid for trimers and hexamers. For a trimer, each interior N-helix of a parallel bundle contacts two exterior C-helices, and each exterior C-helix contacts two interior N-helices. Approximate residue numbers are displayed.

The FP region is represented as extended and β strand structure, based both on reduced average helicity for constructs that include the FP, and on earlier NMR and infrared data that evidence FP antiparallel β sheet structure in membrane.31, 45, 58 Such structure is reasonable for a hexamer for which the strands from the two trimers are interleaved (Fig. 10A). Quantitative analysis of the 13C NMR spectrum of gp41512–581/SGGRGG/628–666 in membrane bilayers also supports predominant α helical structure for non-FP regions and β structure for the FP segment.18 NMR data also support a distribution of N-terminal antiparallel β sheet registries for the FP, with significant populations of registries like 512→527/527→512 for adjacent strands.45 FP insertion in a single leaflet is evidenced by NMR contacts between multiple FP residues and lipid tails.59 There is not close contact between the FP and the MPER or between the FP and the TM, as evidenced by absence of NMR crosspeaks between these domains.34

Figure 10.

Schematic illustrating (A) trimer and (B) monomer respectively favored in the absence and presence of peptide inhibitor. Panel B displays “C34” inhibitor which contains C-helix residues 628–661. C34 binding to the N-helix may require dissociation of the C-helix from the N-helix. The sequence color coding matches Figures 1 and 9, and loops between structured regions are not displayed for clarity. The FP’s from different trimers or monomers adopt antiparallel β sheet structure, and the trimeric TM bundle is based on a TM peptide structure.28, 58 Fusion is enhanced in panel A vs. B because of greater clustering of membrane-perturbing protein regions in the trimer vs. monomer. This enhancement exists for the displayed hemifusion state as well as membrane states that precede hemifusion.

Similar structures of the monomer and trimer forms of FP_HM_TM in Figs. 9 and 10 are supported by previous observations that both oligomeric species exhibit similar structural properties that include: (1) θ222 values which correlate with high fractional helicity; and (2) values of Tm > 90 oC.11, 17, 29, 34, 37, 40, 47 These properties underlie the Figs. 9 and 10 models of the soluble ectodomain regions showing well-defined secondary and tertiary structures that match the high-resolution structure of the trimer.12–14 One conundrum is understanding how gp41 can be both structurally hyperthermostable with Tm ≈ 110 oC and ΔHm ≈ 60 kcal/mole, and also exhibit NMR relaxation data (for the trimeric species) that are consistent with large-amplitude internal motions in the ns-ms timescale.17, 18, 34, 37 These NMR data have been interpreted to support a model of dynamic equilibrium between a compact trimer-ofhairpins and a trimer-of-extended N- and C-helices.

Relationship between vesicle fusion and HIV/cell fusion

Mature HIV virions contain a complex of the gp41 ectodomain trimer in non-covalent association with three gp120 subunits.7, 10 It is not known whether gp41 in the initial complex is its lowest free-energy state. However, for the influenza virus hemagglutinin fusion protein, calorimetric data are consistent with a lowest free-energy state for the initial trimeric HA1/HA2 complex at neutral pH.60 Binding of the HIV gp120 subunits to cellular receptors leads to separation of gp120 from gp41, and then transformation of the secondary and tertiary structure of the gp41 ectodomain into the final hyperthermostable hairpin state.11 Virus/cell membrane fusion is catalyzed by the gp41 ectodomain, and the FP likely binds to the target cell membrane early in the fusion process.3, 29, 59 There is not yet imaging that probes gp41 structure during fusion, and it therefore is not known which gp41 structure(s) mediate the different steps of membrane fusion. Gp41 is unlikely to catalyze fusion in its initial complex with gp120 because the FP is not positioned to reach the cell membrane and because there is not a clear path for lipids to flow around the large complex. The present study describes vesicle fusion induced by gp41 in its final hairpin state in the absence of gp120, which is a candidate structure for catalyzing some steps of HIV/cell fusion. The hairpin role in fusion is supported by: (1) monomer hairpins as a potential target of fusion inhibitors (Fig. 10B); and (2) the reasonable hypothesis that hairpin formation apposes the viral and cell membranes prior to fusion via TM attachment to the viral membrane and FP attachment to the cell membrane.19, 29 In addition, many steps of cell-cell fusion are induced by the influenza virus hemagglutinin subunit II (HA2) fusion protein in its final hairpin conformation.61, 62 HA2 has significant structural similarity with gp41, including trimeric prefusion state with receptor protein (gp41/gp120 and HA2/HA1 complexes), and final hairpin structure in the absence of receptor protein.63, 64

The gp41 proteins of the present and many previous studies are recombinantly produced in bacteria and lack the post-translational glycosylations of gp41 produced in human cells. Lack of glycosylation likely does not impact virus/cell fusion, as detailed in two recent studies that examined properties of the five glycosylation sites of the gp41 ectodomain.65, 66 N616 is the only site for which there can be large reduction in viral infectivity with loss of glycan, although there are HIV strains for which there is no reduction associated with this loss. Loss of infectivity with removal of N616 glycan is highly correlated with inability to form a gp41/gp120 complex, rather than with loss of gp41 fusion function. Lack of glycans at other sites resulted in ~6-fold reduction of the IC50 for viral replication by the T-20 fusion inhibitor, which is consistent with efficient fusion in the absence of these glycans.

The vesicle fusion data of the present study provide information about the relative membrane perturbations of different hairpin constructs that were added as trimer, or trimer + hexamer, without detectable monomer fraction (Fig. 6A). Membrane binding will likely be in these initial oligomeric states, which reflect trimer as the initial gp41 ectodomain state in complex with gp120 and probably also the final hairpin state without gp120. Vesicle binding by gp41 trimers contrasts with many previous vesicle fusion studies for which the gp41 ectodomain was likely predominantly monomeric.29, 46

For the present study, stock protein was principally hyperthermostable trimers and the protein:lipid ratio of ~1:450 implies ~60 protein trimers per vesicle when there is quantitative protein binding, and smaller copy number with reduced binding. This is close to the typical ~15 trimers per virion, with significant microscopy and functional evidence that trimers are spatially clustered during HIV/cell fusion.67–69

Earlier studies of vesicle fusion induced by large gp41 ectodomain constructs like HM, and FP_HM often showed strong dependences on pH and membrane charge that were interpreted as supporting a large contribution to fusion from protein/vesicle electrostatic attraction.17, 29, 30, 46 There was similarly much greater leakage of anionic vesicles at low vs. neutral pH.41 For the present study, electrostatic effects were much less pronounced, as evidenced by smaller dependences of fusion extents on low vs. neutral pH and anionic vs. neutral vesicles (Figs. 7, 8, S6). Fusion extent is a little higher at low vs. neutral pH, and extent at low pH is a little higher with PC+Chol vs. PC+PG+Chol, whereas extent at neutral pH exhibits the opposite trend with vesicle composition. Higher fusion extent at low vs. neutral pH correlates with a large difference in magnitudes of protein charge, ~ +10 vs. –1. Higher extent at low pH with neutral vs. anionic vesicles correlates with reduced bulk protein/vesicle electrostatic attraction that may allow for greater protein and lipid conformational flexibilities. There is also correlation to vesicle fusion observed at neutral pH with short FP (gp41512–534) or MPER/TM (gp41671–693) peptides that have large positive charges from non-native lysines appended to increase aqueous solubility.70, 71

For the present study, large ectodomain constructs with FP and/or TM segments induced significant fusion at neutral pH of both neutral and anionic vesicles, which reflects expected physiologic conditions of HIV/host cell fusion.51 Fusion under physiologic conditions for the present but not earlier studies may be due to inclusion of more hydrophobic segments in the present study, and also stock solutions with predominant trimer in the present study vs. monomer in previous studies.29, 46 The contribution of the hydrophobic effect is evidenced by highest fusion for FP_HM_TM which contains the highly-conserved FP and TM segments.72, 73 The fusion efficiency of trimer vs. monomer may be due to increased local concentration of FP and TM, and correlates with much higher vesicle fusion induced by FP’s that are cross-linked at their C-termini, with topology similar to that in the hairpin trimer.70 Membrane perturbation is magnified in the fusion rate by the Arrhenius Law, assuming that the perturbations reduce activation energy by making membranes more like the fusion transition state. Previous studies have evidenced FP and TM contributions to fusion that are either sequence-specific or that reflect overall hydrophobicity. Example sequence-specific effects are large reductions in gp160-mediated cell-cell fusion associated with mutations like V513E (FP) and R696D (TM).3, 73 Hydrophobicity effects are evidenced by comparable extents of vesicle fusion induced by WT- and residue-scrambled FP’s, and by efficient cell-cell fusion and HIV infectivity after replacement of the gp41 TM with the TM from another membrane protein.74, 75 There are also non-fusion related effects of FP- and TM-mutations that include reductions of HIV-associated immune suppression and intracellular trafficking of gp160.76, 77

Efficient vesicle fusion at physiologic pH by the trimer-of-hairpins may provide insight into how peptides corresponding to N- or C-helix regions inhibit fusion up to the final pore expansion step, which is after inter-membrane lipid mixing and pore formation (Fig. 10).19 These peptides would likely not tightly bind to the trimer-of-hairpins and we propose that they instead bind to monomer hairpins formed from dissociation of the trimer. Such dissociation has been known for twenty years, with additional recent data from our and other groups, and could plausibly occur during the ~30-minute HIV/cell fusion time.2, 29, 33, 36, 40, 41 The bound peptides would prevent re-association into the fusion-efficient trimer. For constructs like FP_HM_TM in DPC detergent at low pH, the 3 monomer ↔ trimer K a ≈ 1012 M–2, so that massmonomer ≈ masstrimer when [total protein] ≈ 1 μM. The membrane Ka has not been measured, but there are comparable statistical-average inter-protein molecular separations of ~100 nm for [bulk protein] ≈ 1 μM, and ~50 nm for ~15 protein trimers in a 100 nm diameter virion. Previous work from our and other groups supports the monomer as the hyperthermostable helical folding unit and it is therefore reasonable that the hairpin is the lowest-free-energy structure.18, 29, 34, 40, 41, 47 Asynchronous folding of monomer protein into hairpin brings the two membranes into apposition and is likely topologically easier than concerted folding of a trimer into a six-helix bundle. It may therefore be evolutionarily advantageous to retain some stability of the monomer hairpin relative to the trimer-of-hairpins.

Kd values have been measured for several systems containing a C-helix peptide and a trimeric gp41 construct. There have been corollary measurements of IC50 values of peptide inhibitions of: (1) gp160-mediated cell-cell fusion; (2) HIV entry into cells; and (3) HIV infection of these cells. For example, the Kd ≈ 1 μM for C34 (gp41628–661) binding to a shorter “6-helix” gp41 (gp41546–579/loop/628–655) ectodomain trimer which has Tm ≈ 80 oC vs. >100 oC for the full ectodomain.20 The Kd ≈ 1 μM for C34 binding to a “5-helix” gp41 ectodomain (gp41543–582/loop/625–662) for which one of the C-helices is absent so that the interior N-helix bundle is exposed for C34 binding.78, 79 5-helix was developed as a surrogate of a hypothesized “pre-fusion intermediate” in which the gp41 ectodomain is extended with C-helices fully separated from the trimeric bundle of N-helices.80 These Kd values are much larger than IC50 ≈ 10 nM for C34 inhibition of gp160-mediated cell-cell fusion and IC50 ≈ 2 nM for C34 inhibition of HIV entry and infection.81, 82 By contrast the Kd for binding to 5-helix was much smaller than IC50’s when 2- or 3- amino acids were added to the N-terminus of C34, with Kd ≈ 1 pM for binding to 5-helix (gp41543–582/loop/625–662), and respective IC50 values for cell-cell fusion, HIV entry, and HIV infection of ~1, 0.5, and 0.5 nM.82, 83 For comparison, the clinically-prescribed T20 (gp41638–673) has Kd ≈ 30 nM for binding with an extended 5-helix (gp41530–582/loop/625–669), and respective IC50 values for cell-cell fusion, HIV entry, and HIV infection of ~25, 25, and 5 nM.83, 84 Given the relative lack of correlation between fusion inhibition and peptide binding to 5-helix or 6-helix gp41 ectodomain, it is plausible that fusion inhibition also has a contribution from peptide binding to monomer hairpins, which we and other groups commonly observe for gp41 ectodomain constructs.

There are similarities between our observations for HIV gp41 and those for non-homologous fusion proteins from other viruses. For example, trimers-of-hairpins of the full-length HA2 protein of the influenza virus catalyze vesicle fusion, and HA2 also exhibits a monomer fraction in SEC.49 There is also evidence for a monomer intermediate during alphavirus fusion.22 There may be a common mechanism of monomer folding into hairpin with subsequent association into trimers which catalyze fusion. This mechanism is supported by hairpin trimers of the HA2 ectodomain inducing lipid mixing and pore formation between docked cells.61, 62 There are similar effects of point mutations for both HA2 ectodomain-induced cell/cell fusion and virus/cell fusion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge support from NIH AI47153 and assistance from the Michigan State University Genomics and Mass Spectrometry facilities.

This work was supported by NIH R01 AI047153.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

analytical ultracentrifugation

- CD

circular dichroism

- Chol

cholesterol

- DPC

dodecylphosphocholine

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FP

fusion peptide

- HP

hairpin construct

- HM

hairpin + MPER construct

- MPER

membrane-proximal external region

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (sodium salt)

- RP

recombinant protein

- Sarkosyl

sodium lauroyl sarcosinate

- SDS

sodium dodecylsulfate

- SE

soluble ectodomain

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- TM

transmembrane domain

Footnotes

Supporting Information

DNA sequences corresponding to protein inserts; 13C NMR of bacterial cell pellets enriched in inclusion bodies; SDS-PAGE of affinity purification eluents for different solubilization conditions of cell pellets; sequence coverages of proteins from peptides created by trypsin digestion and identified by mass spectrometry; original and replicate traces of size exclusion chromatography; additional fusion extent data including dose dependence. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- [1].Grewe C, Beck A, and Gelderblom HR (1990) HIV: early virus‐cell interactions, J. AIDS 3, 965–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Blumenthal R, Durell S, and Viard M (2012) HIV entry and envelope glycoprotein‐mediated fusion, J. Biol. Chem 287, 40841–40849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Freed EO, Delwart EL, Buchschacher GL Jr., and Panganiban AT (1992) A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 dominantly interferes with fusion and infectivity, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 89, 70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Postler TS, and Desrosiers RC (2013) The tale of the long tail: the cytoplasmic domain of HIV‐1 gp41, J. Virol 87, 2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Julien J‐P, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumukis D, Deller MC, Klasse P‐J, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Ward AB, and Wilson IA (2013) Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV‐1 envelope trimer, Science 342, 1477–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lyumukis D, Julien J‐P, de Val N, Cupo A, Potter CS, Klasse P‐J, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Carragher B, Wilson IA, and Ward AB (2013) Cryo‐EM structure of a fully glycosylated soluble cleaved HIV‐ 1 envelope trimer, Science 342, 1484–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pancera M, Zhou TQ, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang JH, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, Stewart‐Jones GBE, Stuckey J, Bailer RT, Joyce MG, Louder MK, Tumba N, Yang YP, Zhang BS, Cohen MS, Haynes BF, Mascola JR, Morris L, Munro JB, Blanchard SC, Mothes W, Connors M, and Kwong PD (2014) Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre‐fusion HIV‐1 Env, Nature 514, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Garces F, Lee JH, de Val N, de la Pena AT, Kong L, Puchades C, Hua Y, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Moore JP, Sanders RW, Ward AB, and Wilson IA (2015) Affinity maturation of a potent family of HIV antibodies is primarily focused on accommodating or avoiding glycans, Immunity 43, 1053–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee JH, Ozorowski G, and Ward AB (2016) Cryo‐EM structure of a native, fully glycosylated, cleaved HIV‐1 envelope trimer, Science 351, 1043–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ozorowski G, Pallesen J, de Val N, Lyumkis D, Cottrell CA, Torres JL, Copps J, Stanfield RL, Cupo A, Pugach P, Moore JP, Wilson IA, and Ward AB (2017) Open and closed structures reveal allostery and pliability in the HIV‐1 envelope spike, Nature 547, 360–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Covell DG, Gronenborn AM, and Clore GM (1998) Three‐dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41, EMBO J. 17, 4572–4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang ZN, Mueser TC, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, and Hyde CC (1999) The crystal structure of the SIV gp41 ectodomain at 1.47 A resolution, J. Struct. Biol 126, 131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Buzon V, Natrajan G, Schibli D, Campelo F, Kozlov MM, and Weissenhorn W (2010) Crystal structure of HIV‐ 1 gp41 including both fusion peptide and membrane proximal external regions, PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shi WX, Bohon J, Han DP, Habte H, Qin YL, Cho MW, and Chance MR (2010) Structural characterization of HIV gp41 with the membrane‐proximal external region, J. Biol. Chem 285, 24290–24298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kong R, Xu K, Zhou TQ, Acharya P, Lemmin T, Liu K, Ozorowski G, Soto C, Taft JD, Bailer RT, Cale EM, Chen L, Choi CW, Chuang GY, Doria‐Rose NA, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Gorman J, Huang JH, Joyce MG, Louder MK, Ma XC, McKee K, O’Dell S, Pancera M, Yang YP, Blanchard SC, Mothes W, Burton DR, Koff WC, Connors M, Ward AB, Kwong PD, and Mascola JR (2016) Fusion peptide of HIV‐ 1 as a site of vulnerability to neutralizing antibody, Science 352, 828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].van Gils MJ, van den Kerkhof TLGM, Ozorowski G, Cottrell CA, Sok D, Pauthner M, Pallesen J, de Val N, Yasmeen A, de Taeye SW, Schorcht A, Gumbs S, Johanna I, Saye‐Francisco K, Liang C‐H, Landais E, Nie X, Pritchard LK, Crispin M, Kelsoe G, Wilson IA, Schuitemaker H, Klasse PJ, Moore JP, Burton DR, Ward AB, and Sanders RW (2017) An HIV‐1 antibody from an elite neutralizer implicates the fusion peptide as a site of vulnerability, Nature Microbiology 2, Art. No. 16199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lev N, Fridmann‐Sirkis Y, Blank L, Bitler A, Epand RF, Epand RM, and Shai Y (2009) Conformational stability and membrane interaction of the full‐length ectodomain of HIV‐1 gp41: Implication for mode of action, Biochemistry 48, 3166–3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]