Abstract

B cells are known to promote the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) via the production of pathogenic anti-nuclear antibodies. However, the signals required for autoreactive B cell activation and the immune mechanisms whereby B cells impact lupus nephritis pathology remain poorly understood. The B cell survival cytokine B cell activating factor of the TNF Family (BAFF) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of SLE and lupus nephritis in both animal models and human clinical studies. Although the BAFF receptor has been predicted to be the primary BAFF family receptor responsible for BAFF-driven humoral autoimmunity, in the current study we identify a critical role for signals downstream of Transmembrane Activator and CAML Interactor (TACI) in BAFF-dependent lupus nephritis. Whereas transgenic mice overexpressing BAFF develop progressive membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, albuminuria and renal dysfunction, TACI deletion in BAFF-transgenic mice provided long-term (about 1 year) protection from renal disease. Surprisingly, disease protection in this context was not explained by complete loss of glomerular immune complex deposits. Rather, TACI deletion specifically reduced endocapillary, but not mesangial, immune deposits. Notably, although excess BAFF promoted widespread breaks in B cell tolerance, BAFF-transgenic antibodies were enriched for RNA- relative to DNA-associated autoantigen reactivity. These RNA-associated autoantibody specificities were specifically reduced by TACI or Toll-like receptor 7 deletion. Thus, our study provides important insights into the autoantibody specificities driving proliferative lupus nephritis, and suggests that TACI inhibition may be novel and effective treatment strategy in lupus nephritis.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, B cell activating factor of the TNF Family (BAFF), Transmembrane Activator and CAML Interactor (TACI), Autoantibodies, Lupus nephritis

Introduction

The B cell survival cytokine B cell activating factor of the TNF Family (BAFF, also known as BLyS) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis.1 For example, independently generated BAFF-Tg (transgenic) mouse strains exhibit humoral autoimmunity recapitulating several cardinal features of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) including polyclonal B cell activation, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) production and the development of immune complex (IC) mediated glomerulonephritis.2, 3 In addition, a prominent subset of patients with lupus patients exhibit increased serum BAFF,4 and an insertion–deletion variant in human TNFSF13B (encoding BAFF), which results in higher serum BAFF levels, was recently demonstrated to confer increased risk of SLE.5 Finally, the BAFF-inhibiting therapeutic antibody, Belimumab, received FDA approval for the treatment of SLE,6, 7 and a post-hoc analysis of renal disease parameters using pooled data from the phase 3 SLE trials demonstrated reduced nephritis in Belimumab treated lupus patients.8 Although the clinical efficacy of Belimumab in these human lupus trials has been relatively modest, these combined animal and human data indicate an important role for BAFF in the pathogenesis of SLE.

BAFF, and the related TNF-family cytokine A Proliferation-Inducing Ligand (APRIL), promote B cell survival and activation by binding distinct receptors on peripheral B cells. BAFF binds both the BAFF receptor (BAFF-R) and Transmembrane Activator and CAML Interactor (TACI), while APRIL preferentially activates cells expressing TACI or B cell maturation antigen (BCMA).1 Since BAFF-R deletion results in a loss of mature B cells,9 this receptor was predicted to be the likely target for BAFF-driven B cell activation in autoimmunity. In contrast to this idea, we and others recently reported the unexpected finding that BAFF-driven production of certain autoantibody specificities requires TACI.10, 11 While these data did not preclude additional roles for BAFF-R and BCMA signals in BAFF-dependent autoantibody production, these findings highlighted the critical importance of TACI activation in facilitating BAFF-driven breaks in B cell tolerance.

Importantly, whether loss of TACI signals protects against BAFF-driven glomerulonephritis has not been fully addressed. Figgett et al. reported decreased glomerulonephritis following TACI deletion. However, renal disease was evaluated at only 12 weeks after reconstitution of lethally-irradiated BAFF-Tg mice with Taci-/- bone marrow (BM)10 and prior studies of BAFF-Tg animals described development of glomerulonephritis in aged animals (∼10-17 months old).12, 13 Therefore, disease quantification at early time-points may not adequately address whether TACI deletion prevents kidney disease, especially when one accounts for the several weeks required to reconstitute the B cell compartment following irradiation.

For this reason, we examined the long-term (up to 1 year) impact of TACI deletion on BAFF-driven kidney disease. We observed protection from progressive glomerulonephritis, albuminuria and renal dysfunction in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. Surprisingly, rather than uniformly blocking BAFF-driven autoantibody formation, TACI deletion specifically reduced titers of class-switched ANA against predominantly RNA-associated autoantigens. Loss of these autoantibody specificities correlated with absent endocapillary, but not mesangial, IC deposits in Taci-deficient BAFF-Tg mice. In addition to identifying TACI as a potential therapeutic target in SLE, these data strongly support a model in which RNA-associated autoantibody specificities can promote endocapillary IC formation and the pathogenesis of proliferative lupus nephritis.

Results

TACI deletion prevents immune activation and hypergammaglobulinemia in BAFF-Tg mice

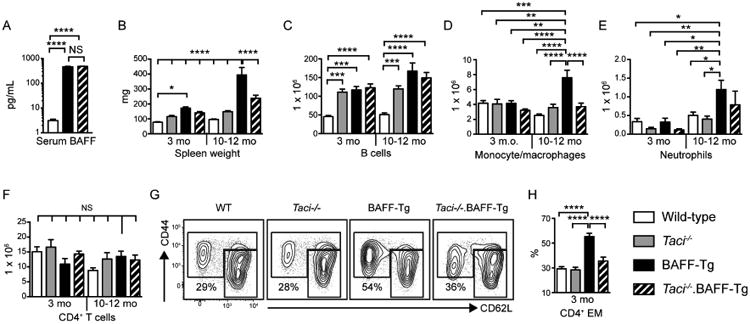

To test the impact of TACI signals on BAFF-driven autoimmunity, we crossed BAFF-Tg and Taci-/- mice.14 Of the several BAFF-Tg models available, we utilized a model over-expressing BAFF within the myeloid compartment under the control of the human CD68 promoter,3 as this most closely mirrors the tissue expression pattern for endogenous BAFF. Importantly, TACI deletion did not reduce serum BAFF levels in BAFF-Tg mice, suggesting that absent TACI expression does not indirectly impact BAFF-driven autoimmunity (Figure 1A). To assess the impact of increased serum BAFF over time, cohorts were sacrificed at both early (3 month) and late (10-12 month) time points. BAFF-Tg mice exhibited pronounced splenomegaly that increased with age, but was attenuated by TACI deletion (Figure 1B). Splenic enlargement was accounted for by marked B cell hyperplasia as well as the TACI-dependent expansion of myeloid cells, including CD11b+GR1lo monocyte/macrophages and CD11b+GR1+ neutrophils, in BAFF-Tg mice (Figure 1C-E). Although the total number of splenic T cells was equivalent (Figure 1F), an increased proportion of CD4+ T cells from BAFF-Tg, but not Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg, mice exhibited an activated effector/memory (CD44hiCD62Llo/hi) phenotype (Figure 1G, H).

Figure 1. Excess BAFF promotes progressive, TACI-dependent immune activation.

(A) Serum BAFF levels in 6-month-old WT (n=5), BAFF-Tg (n=8) and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (n=8) mice. (B-F) Spleen weight (B) and total number of splenic CD19+ B cells (C), CD11b+GR1lo monocyte/macrophages (D), CD11b+GR1+ neutrophils (E) and CD4+ T cells (F) in WT, Taci-/-, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice sacrificed at 3 and 10-12 months old. (G, H) Representative flow plots (G; gated on CD4+ T cells) and percentage of CD4+ T cells exhibiting CD44hiCD62Llo/hi effector/memory phenotype (H) from 3-month-old mice of indicated genotypes. Number equals percentage in CD44hiCD62Llo/hi EM gate. (B-H) n=11-16 mice analyzed per group. (A-H) Error bars indicate SEM; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001, NS, not significant; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test.

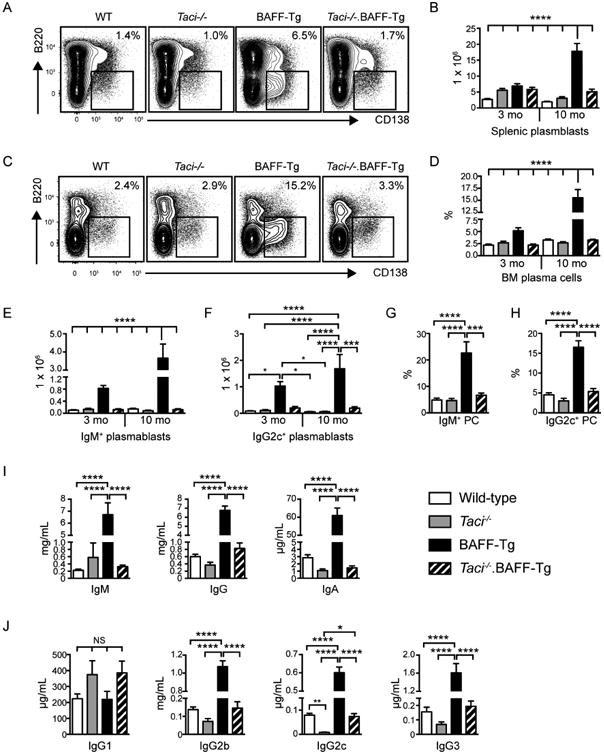

Despite similar B cell numbers in 3-month-old BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg animals, TACI signals promoted B cell activation in BAFF-Tg mice. Specifically, aged BAFF-Tg mice exhibited a prominent expansion of splenic B220loCD138+ plasmablasts and B220-CD138+ BM plasma cells (Figure 2A-D), including both IgM+ unswitched and class-switched IgG2c+ antibody secreting cells (Figure 2E-H). Consistent with these data, TACI deletion in BAFF-Tg mice markedly reduced total serum immunoglobulin across immunoglobulin isotypes and subclasses. For example, serum IgM, IgG and IgA levels were decreased in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg relative to BAFF-Tg mice by ∼95%, 85% and >98%, respectively, with the complement-fixing isotypes IgG2b and IgG2c most impacted by TACI deletion (Figure 2I, J). Thus, chronic BAFF elevation results in progressive immune activation and hypergammaglobulinemia, and TACI is the predominant BAFF-binding receptor responsible for these events.

Figure 2. BAFF signals via TACI to promote B cell activation.

(A, B) Representative flow plots (A) and total number (B) of splenic B220loCD138+ plasma cells/plasmablasts in WT, Taci-/-, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice sacrificed at indicated ages. (C, D) Representative flow plots (C) and percentage (D) of BM B220negCD138+ plasma cells/plasmablasts in WT, Taci-/-, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice sacrificed at indicated ages. (A, C) Flow plots are representative of indicated genotypes sacrificed at 10-12 months, gated on total splenocytes (A) and total BM cells (C), respectively. Number equals percentage within gate. (E, F) Number of isotype-specific IgM+ (E) and IgG2c+ (F) splenic plasmablasts in WT, Taci-/-, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. (G, H) Percentage of BM plasma cells expressing IgM (G) and IgG2c (H) by intracellular staining, from indicated genotypes sacrificed at 10-12 months. (I, J) Total serum IgM, IgG and IgA titers (I), and lgG1, lgG2b, lgG2c and lgG3 subclass titers (J) in 3-month-old mice of indicated genotype. (A-H) Error bars indicate SEM; *, P<0.05; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test (n=9-12 mice analyzed per group).

TACI signals promote BAFF-driven albuminuria and renal dysfunction

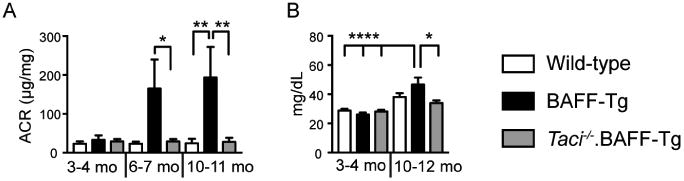

We next evaluated whether decreased immune activation in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice correlated with biomarkers of renal disease. Although BAFF-Tg mice lacked proteinuria at early time points, by 6 months the majority of BAFF-Tg animals developed albuminuria (Figure 3A), with the degree of albuminuria increasing with age. Using an albumin:creatinine ratio cutoff (corresponding to mean + 4 standard deviations of 3-month-old WT controls), at 6-7 months 71% of BAFF-Tg exhibited proteinuria compared with 0% of Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice (P<0.005 by Fisher's exact test). By 10-11 months, 67% of BAFF-Tg mice developed albuminuria compared with 1 out of 11 (9%) Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice (P<0.05 by Fisher's exact test). Whereas McCarthy et al. previously noted a gender bias in the rate of renal disease progression in BAFF-Tg mice,12 we observed no difference in the development of albuminuria in male vs. female BAFF-Tg animals (data not shown). Consistent with albuminuria serving as a biomarker of future declines in renal function, by 10-12 months of age, BAFF-Tg, but not Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg, mice exhibited renal dysfunction based on elevated serum BUN concentrations (Figure 3B). Together, these data demonstrate that TACI deletion protects BAFF-Tg mice from progressive albuminuria and renal dysfunction.

Figure 3. Excess BAFF promotes TACI-dependent albuminuria and renal dysfunction.

(A) Urine albumin:creatinine (ACR) ratio (μg/mg) in aged cohorts of WT, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice, demonstrating that BAFF over-expression promotes progressive albuminuria in a TACI-dependent manner. Total number of animals analyzed at 3-4 months, 6-7 months and 10-11 months: WT (n=5, 7, 10); BAFF-Tg (n=5, 7, 6); and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (n=5, 10, 11). (B) Serum BUN in aged cohorts of indicated genotypes, showing that increased BAFF promotes TACI-dependent renal dysfunction. Total number of animals analyzed at 3-4 months and 10-12 months: WT (n=7, 6); BAFF-Tg (n=7, 7); and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (n=7, 7). (A, B) Error bars indicate SEM. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ****, P<0.0001; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test.

Progressive membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice is prevented by TACI deletion

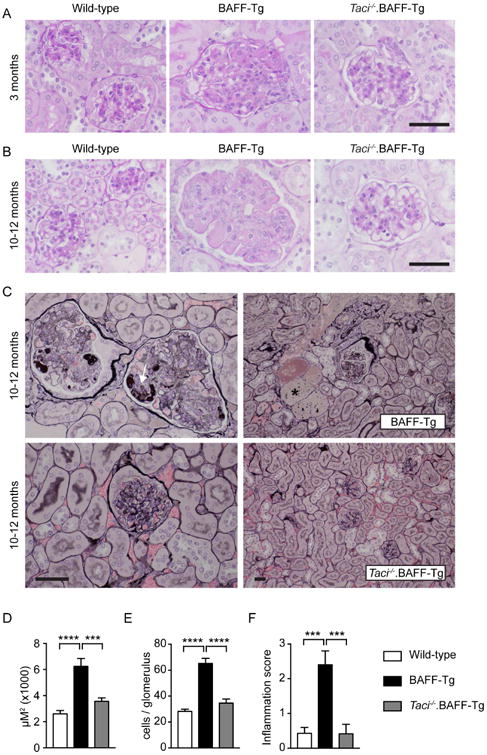

We next characterized the impact of TACI signals on the progression of BAFF-driven glomerulonephritis with age. At 3 months of age, BAFF-Tg mice exhibited only mild mesangial expansion with limited mesangial inflammatory infiltrates (Figure 4A); features that were absent in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. However, by 10-12 months, BAFF-Tg mice developed severe membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) characterized by mesangial hypercellularity, increased mesangial matrix and accumulation of eosinophilic material within the glomerular capillaries (Figure 4B). Analysis of sections stained with Jones' methenamine silver stain identified prominent focal mesangiolysis and duplication of the glomerular capillary basement membranes with focal intracapillary accumulations of acellular material, which stained intensely with the silver methenamine preparations. In addition, we observed focal accumulations of proteinaceous material within dilated tubules as well as scattered interstitial inflammation (Figure 4C). Importantly, these changes were not observed in WT, Taci-/-, and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice (Figure 4A-C). Computer-assisted quantification of mean glomerular size and cell count per glomerulus demonstrated glomerular expansion and cellular infiltration in 10-month-old BAFF-Tg mice, that was absent in WT and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice (Figure 4D, E). Finally, blinded scoring of the severity of glomerular inflammation confirmed prominent glomerular inflammation in BAFF-Tg mice, which was abrogated by TACI deletion (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. TACI deletion prevents progressive glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice.

(A, B) Representative periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained renal sections showing mild mesangial expansion and inflammatory cell infiltration in 3-month-old (A) BAFF-Tg mice, with progressive mesangial expansion, hypercellularity and endocapillary eosinophilic deposits in aged BAFF-Tg mice (B). These pathologic changes were inapparent in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. (C) Jones' methenamine silver stained kidney sections showing marked mesangiolysis, capillary basement membrane duplication and accumulation of silver-dense material (arrow) within the glomerular capillaries in representative aged BAFF-Tg mouse (upper left panel). Aged BAFF-Tg animals also exhibited prominent proteinaceous casts (*) within dilated tubules (upper right panel). Notably, TACI deletion prevented these pathologic changes for up to 1 year (lower panels). (A-C) Bars: 50μm. (D, E) Mean glomerular size (D) and mean cell count per glomerulus (E) in 10-12-month-old WT (white), BAFF-Tg (black) and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (gray) mice. (F) Severity of glomerular inflammation scored as: normal (0+); focal glomerular changes with mild mesangial expansion and hypercellularity (1+); moderate mesangial expansion, GBM thickening/reduplication and glomerular hypercellularity (2+); and diffuse glomerular changes with severe mesangial expansion, GBM thickening/reduplication and glomerular hypercellularity (3+). Pathology was scored by two independent observers blinded to genotype. (D-F) Error bars indicate SEM. ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. (A-F) Total mice analyzed: n=9-11 per genotype.

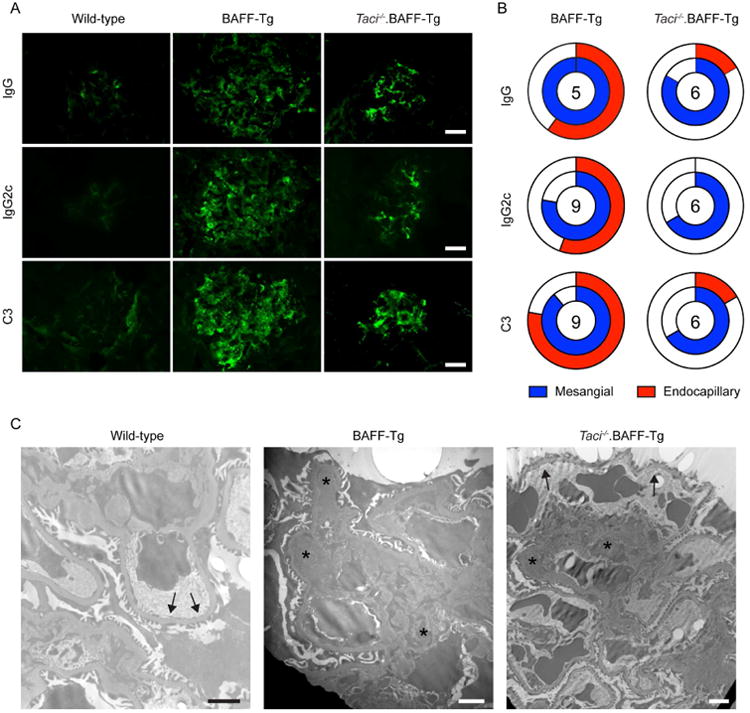

Consistent with prominent roles for class-switched autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis, we observed glomerular IgG deposits in BAFF-Tg mice including antibodies of the pathogenic IgG2c subclass, capable of fixing complement and binding activating Fc-receptors on the surface of myeloid cells.15 In keeping with the likelihood that complement-fixing immunoglobulin isotypes promote renal disease,16-18 BAFF-Tg mice developed distinct C3 complement deposits (Figure 5A). Although a separate BAFF-Tg strain developed renal disease resembling human IgA nephropathy,12 we observed no glomerular IgA deposition (data not shown); findings that may reflect differences in serum BAFF levels and/or in microbial flora between these models.

Figure 5. TACI deletion prevents BAFF-driven endocapillary, but not mesangial, immune complex deposits.

(A) Representative IF staining for glomerular IgG, lgG2c, and C3 complement in indicated genotypes, showing both mesangial and capillary wall IC deposits in BAFF-Tg mice. In contrast, deposits were limited to the mesangium in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. Bars: 20μm. (B) Location of glomerular deposits, scored as mesangial (blue) and/or endocapillary (red), in BAFF-Tg vs. Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. Unfilled portion of circle represents animals with absent or undefinable IF staining pattern, and number within circle indicates number of animals analyzed. Scoring was performed by observer blinded to genotype. (C) Representative electron micrographs showing prominent mesangial (arrowheads) and capillary wall immune complexes (stars) in BAFF-Tg mice, but no capillary wall deposits in wild type (WT) mice (arrows). In contrast to BAFF-Tg mice, immune deposits were limited to the mesangium in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice (arrowheads), while capillary loops lacked deposits (arrows). Bars: 2μm.

Since BAFF-driven hypergammaglobulinemia and autoantibody formation is TACI dependent (Fig 2I, J, and 10, 11), we predicted that lack of glomerulonephritis following TACI deletion would be explained by a complete loss of glomerular IC deposits. In contrast with this idea and the findings of Figgett et al.,10 aged Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice exhibited IgG, IgG2c and C3 immunofluoresence staining of similar intensity to BAFF-Tg mice, and of markedly greater intensity than age-matched WT controls (Figure 5A). However, whereas BAFF-Tg mice exhibited both endocapillary and mesangial IF staining patterns, in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice these deposits were limited to the mesangium (Figure 5A, B). Using a blinded assessment of the location of glomerular deposits, 56% BAFF-Tg vs. 0% Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice showed endocapillary IgG2c deposition (P<0.05 by Fisher's exact test), while 78% BAFF-Tg vs. 17% Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice exhibited endocapillary C3 complement staining (P<0.05 by Fisher's exact test). To confirm these distinct IC deposition patterns, we performed electron microscopy of animals within the aged cohort. Notably, BAFF-Tg mice developed extensive IC deposition, both in the mesangial and in subendothelial regions. In contrast, Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice exhibited prominent IC deposits within the mesangium, but not within the capillary walls (Figure 5C).

Together our data demonstrate that TACI deletion results in sustained protection from progressive IC glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice. However, rather than preventing renal IC formation, TACI deletion specifically reduces the development of endocapillary deposits, thereby limiting BAFF-driven albuminuria and progressive renal dysfunction.

TACI deletion in BAFF-Tg mice specifically reduces autoantibodies targeting RNA-associated self-antigens

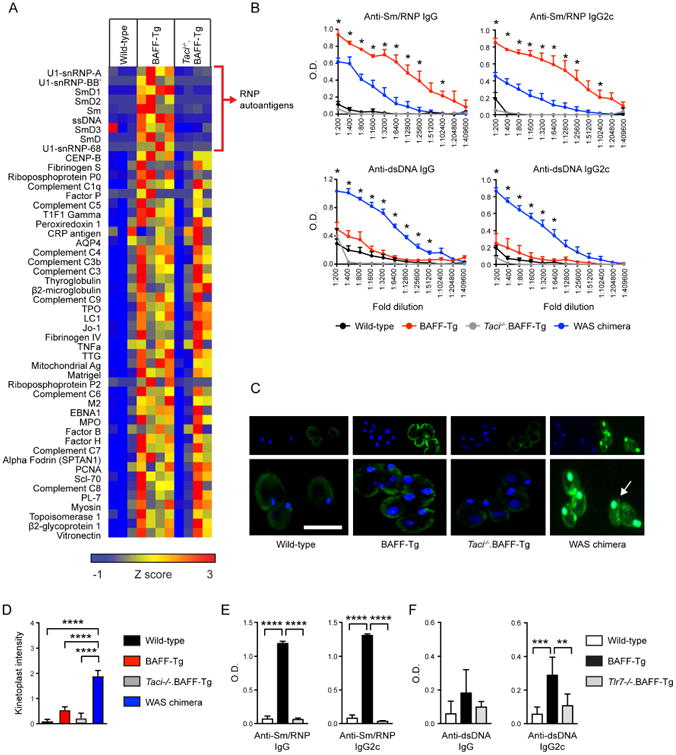

These observations raised the question of how to reconcile the distinct IC staining patterns in BAFF-Tg vs. Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice with changes in serum immunoglobulin and autoantibody titers following TACI deletion. Specifically, Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice exhibit extensive mesangial IC deposits compared with WT controls, suggesting that certain BAFF-driven antibody specificities are preserved following TACI deletion. To test this idea, we performed a detailed analysis of the autoantibody repertoire in WT, BAFF-Tg, and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice using a microarray analysis including 123 distinct autoantigens.19 Notably, the BAFF-Tg autoantibodies exhibiting the highest reactivity by microarray targeted a range of RNA-associated specificities, including RNA-binding proteins within the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex (U1-snRNP-A, U1-snRNP-BB′, U1-snRNP-68) and Smith (Sm, SmD, SmD1, SmD2, SmD3) antigens. These findings contrasted with previous reports of high-titer anti-double stranded DNA (dsDNA) autoantibodies in independent BAFF-Tg models.2, 13 Strikingly, autoantibodies against these RNA-associated specificities were abrogated by TACI deletion, whereas reactivity to multiple other autoantigens were largely equivalent in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg and BAFF-Tg mice, and markedly increased relative to WT controls (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. TACI signals promote class-switched autoantibodies against RNA-associated autoantigens in BAFF-Tg mice.

(A) Serum IgG autoantibodies in wild-type, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice, determined using an autoantigen microarray. Specific autoantigens are ordered from top to bottom based on intensity of BAFF-Tg IgG reactivity. Surprisingly, TACI deletion results in the loss of a limited subset of BAFF-Tg autoantibodies (depicted by red bracket), enriched for ribonucleoprotein (RNP) reactivity. Data are represented as a heat map of Z-scores ranging from -1 (blue) to 3 (red). Each column represents an independent animal. (B) Anti-Sm/RNP (upper panels) and anti-dsDNA (lower panels) IgG and lgG2c autoantibodies in sera from wild type (black, n=2), BAFF-Tg (red, n=5), Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (gray, n=5), and the WAS chimera lupus model (blue, n=5). Whereas antibodies binding the RNA-associated autoantigen Sm/RNP were significantly increased in BAFF-Tg mice compared with the WAS chimera model, titers of dsDNA autoantibodies were markedly lower in BAFF-Tg vs. WAS chimera mice. Error bars indicate SEM; *, P<0.05, BAFF-Tg vs. WAS chimera reactivity by two-tailed Student's t test. (C) Representative images of C. luciliae stained with IgG (green) and DAPI (blue). Arrow highlights prominent IgG and DAPI counterstaining of the C. luciliae kinetoplast by WAS chimera sera. In contrast, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg sera exhibited variable diffuse staining of C. luciliae cytoplasm, without increased kinetoplast reactivity. Bars: 10μm. (D) Anti-dsDNA IgG Ab by intensity of C. luciliae kinetoplast staining in wild-type (black, n=12), BAFF-Tg (red, n=18), Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (gray, n=5), and WAS chimera (blue, n=14) sera. Kinetoplast staining was scored from 0-3 by observers blinded to genotype. (E, F) Anti-Sm/RNP (E) and anti-dsDNA (F) IgG and lgG2c autoantibodies in 4-month-old wild-type (white, n=6), BAFF-Tg (black, n=7), and Tlr7-/-.BAFF-Tg (gray, n=4) sera. (D-F) Error bars indicate SEM. **, P<0.01, ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test.

The relative enrichment for RNA- relative to DNA-reactive autoantibodies in BAFF-Tg mice by microarray was notable since human lupus nephritis has been most closely linked with anti-dsDNA antibodies.20 To confirm the specificity of these microarray data, we performed autoantigen ELISAs for dsDNA and the RNA-associated autoantigen Sm/RNP in WT, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. As a comparison, we also quantified serum autoantibodies from a separate murine lupus strain, termed the WAS chimera model, that is characterized by the development of high-titer, class-switched ANA targeting both dsDNA and RNA-associated autoantigens.18, 21, 22 Consistent with the microarray data, anti-Sm/RNP IgG autoantibodies were markedly increased in BAFF-Tg mice, compared with WT controls, Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice and with autoimmune WAS chimera serum. In contrast, BAFF-Tg anti-dsDNA titers were only modestly elevated compared with WT serum, and significantly reduced compared with the WAS chimera model (Figure 6B; left panels). These trends in relative DNA- vs. RNA-reactive autoantibody abundance between lupus strains were confirmed by subclass-specific ELISAs for pathogenic IgG2c autoantibodies (Figure 6B; right panels). In keeping with the microarray data, Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg lacked autoantibodies against both Sm/RNP and dsDNA.

Importantly, several previous studies using TLR9-deficient murine lupus models have demonstrated that anti-dsDNA testing by ELISA lacks specificity for DNA, with RNA-associated autoantibodies exhibiting cross-reactive binding on standard ELISAs.18, 23, 24 For this reason, we also measured serum anti-dsDNA antibodies in BAFF-Tg mice by the highly-specific Crithidia luciliae assay. Notably, WAS chimera sera exhibited high intensity binding to native DNA within C. luciliae kinetoplast, whereas BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg sera reacted predominantly against cytoplasmic antigens with only low-intensity IgG kinetoplast staining (Figure 6C, D). These findings are particularly notable given the ∼4 fold increase in total serum IgG in BAFF-Tg mice relative to the WAS chimera model (Fig. 1A and 18, 22).

Finally, we sought to address the mechanisms underlying prominent RNA-associated autoantibody production in BAFF-Tg mice. Despite a wide range of potential autoantibody targets, lupus sera frequently exhibit predominant reactivity to nuclear antigens, an observation explained by dual B cell receptor (BCR)- and toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated activation of autoreactive B cells following recognition of nucleic acid-containing apoptotic particles.25-27 In this context, B cell-intrinsic expression of the endosomal toll-like receptors TLR7 and TLR9 is required for the generation of autoantibodies targeting RNA- or DNA-associated antigens, respectively.18, 24 Previous studies have demonstrated that BAFF-dependent TACI activation promotes TLR7 expression,28 and that B cell TLR7 signals reciprocally induce upregulation of surface TACI.13 Since TLR7 overexpression is sufficient to promote breaks in B cell tolerance,29, 30 these data suggest that altered B cell TLR7 responses may explain the enrichment for RNA-associated autoantigen reactivity in BAFF-Tg mice. To test this idea, we stimulated FACS-sorted follicular mature (FM) B cells from WT, BAFF-Tg, and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice with TLR7 (R848) or TLR9 (CPG) agonists. Notably, relative to WT controls, BAFF-Tg B cells exhibited enhanced proliferation and increased surface expression of the activation marker CD80 in response to either R848 or CPG stimulation. However, this increase in TLR7 and TLR9 responses was also observed in B cells from Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg animals, suggesting that enhanced TLR-dependent activation in BAFF-Tg mice occurs in a TACI-independent manner (Supplemental Figure 1A-D). Consistent with these data, we observed no difference in Tlr7 and Tlr9 transcript levels between BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg splenic B cells (Supplemental Figure 1E). Together these data show that, whereas enhanced TLR7 responses likely account for the predominance of RNA-associated autoantibodies in BAFF-Tg mice, reduced TLR7 activity does not explain the lack of class-switched autoantibodies in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice.

Finally, to definitively establish that TLR7 is the innate receptor required for BAFF-mediated RNA-associated autoantibody production, we crossed BAFF-Tg and TLR7-deficient (Tlr7-/-) mice. As predicted, TLR7 deletion prevented class-switched anti-Sm/RNP autoantibodies in BAFF-Tg mice (Figure 6E). Strikingly, anti-dsDNA autoantibodies, in particular those of the pathogenic IgG2c subclass, were also significantly reduced in Tlr7-/-.BAFF-Tg mice, providing additional support for our hypothesis that the majority of serum “DNA-reactive” autoantibodies in BAFF-Tg mice identified using standard anti-dsDNA ELISAs represent cross-reactive, TLR7-dependent, RNA-associated autoantibodies (Figure 6F).

In summary, BAFF over-expression promotes autoantibody production against a wide range of disease-associated autoantigens, with these autoantigens being enriched for RNA-associated specificities. Importantly, rather than a general requirement for TACI in BAFF-driven autoantibody formation, TACI signals integrate with TLR7 activation to specifically promote the generation of class-switched ANA targeting RNA-associated antigens. These findings strongly suggest that, whereas mesangial IC deposits may be generated by a broad array of autoantibody specificities, RNA-associated autoantibodies can promote endocapillary IC formation and drive progressive glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice.

Discussion

Of the protean clinical features of SLE, the development of lupus nephritis results in markedly increased morbidity and mortality.31 Despite advances in the development of targeted immunosuppressive therapies, effective and safe treatments for lupus nephritis are lacking. Using a specific murine lupus model in which disease development is driven by transgenic BAFF over-expression, we have identified a critical role for TACI activation in the production of pathogenic autoantibodies and the development of progressive IC glomerulonephritis. Although no murine lupus model can fully recapitulate the complex and heterogeneous clinical phenotypes of human SLE, our data suggest that TACI inhibition may serve as an effective therapy in lupus nephritis, in particular for the subset of patients in which disease is driven by increased BAFF.

An important finding of our study is that BAFF-Tg sera are enriched for RNA-associated autoantibody specificities. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that B cells from BAFF-Tg mice exhibit markedly enhanced TLR7 responses ex vivo, and TLR7 signals are required for RNA-associated autoantibody production in vivo, indicating that integration of BAFF and TLR7 signals is critical for BAFF-driven autoantibody production. Surprisingly, despite the complete lack of RNA-associated autoantibodies in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice, the enhanced B cell TLR7 response in BAFF-Tg animals was not impacted by TACI deletion. To reconcile these seemingly paradoxical findings, we propose the following model for how integrated B cell TLR7 and TACI signals promote BAFF-driven breaks in B cell tolerance. Since BAFF facilitates the survival and maturation of low-affinity autoreactive B cells,32-34 we predict that excess BAFF first skews the mature B cell repertoire towards increased autoreactivity. Subsequently, self-reactive B cells binding nucleic acid-containing autoantigens undergo dual BCR- and TLR7-mediated activation, with these signals enhanced by elevated basal TLR7 responses. Moreover, signals downstream of BCR and/or TLR7 likely also promote TACI expression on the surface of autoreactive B cells.11, 13, 35 In this setting, engagement of surface TACI expressed on autoreactive B cells by circulating BAFF multimers would be predicted to drive differentiation into autoantibody-secreting plasma cells, in keeping with established roles for TACI signals in T-independent antibody production by murine and human B cells.36-38 Notably, deletion of either TACI or TLR7 expression similarly prevented RNA-associated autoantibody formation in BAFF-Tg mice (see Figure 6), indicating that integrated signals downstream of both TLR7 and TACI ligation are critical for breaks in B cell tolerance and the development of pathogenic, autoantibody-producing plasma cells.

An important outstanding question pertinent to this model is why DNA-reactive autoantibodies are not similarly increased in BAFF-Tg mice. Specifically, although increased BAFF promoted an equivalent increase in ex vivo B cell proliferation after stimulation with the TLR9-ligand CPG, titers of anti-dsDNA antibodies were markedly lower in BAFF-Tg mice compared with RNA-associated specificities. In this context, we believe that recent observations from Dr. Marshak-Rothstein's group are particularly relevant. Using the AM14 model in which transgenic B cells can be activated by IgG2a immune complexes, Nündel, et al. demonstrated that engagement of endosomal TLR7 by nucleic acid-containing immune complexes promotes plasma cell differentiation in vivo. In contrast, similar dual BCR and TLR9 signals failed to induce plasma cell formation, and TLR9 signals restrained TLR7-mediated plasma cell differentiation.39 Although addressing the fate of individual autoreactive B cells in the polyclonal BAFF-Tg model is technically challenging, we believe that these observations using AM14 B cells likely mirror the functional roles of TLR7 vs. TLR9 during extra-follicular, T-independent B cell activation in high BAFF settings.

Finally, despite a complete loss of antinuclear specificities in Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice, excess BAFF also promoted autoantibodies against a broad range of tissue autoantigens in a TACI-independent manner (see Figure 6A). While these specificities were insufficient to promote renal pathology, these data indicate that at least two distinct mechanisms underlie B cell activation and autoantibody production in high BAFF settings. In addition to TACI promoting T-independent antinuclear antibody formation via the mechanisms described above,13, 14, 36 we predict that TACI-independent autoantibody specificities are generated in parallel following autoreactive B cell interactions with cognate T cells; data consistent with roles for BAFF in promoting germinal center formation.40, 41

Beyond these mechanistic events, our study provides additional insights into the pathophysiology of lupus nephritis. An important unanswered question in the field is which autoantibody specificities promote glomerular inflammation, and whether different autoantibody specificities facilitate IC formation at distinct glomerular sites. Based on clinical data that anti-dsDNA antibodies in SLE correlate with the development of lupus nephritis and that increased anti-dsDNA titers may predict renal flares,20, 42 prior research has focused primarily on roles for DNA/chromatin-reactive antibodies. Consistent with this hypothesis, anti-dsDNA antibodies have been eluted from lupus nephritis kidneys43 and the transfer of some (but not all) anti-DNA monoclonal antibodies promotes proteinuria in animal models.44

In contrast to this idea, we now report the surprising observation that progressive IC glomerulonephritis in BAFF-Tg mice develops in the setting of high-titer RNA-associated autoantibodies, relative to DNA-reactive specificities. While a subset of BAFF-Tg mice developed low-titer anti-dsDNA autoantibodies (as assessed by stringent C. luciliae kinetoplast reactivity), unbiased assessment of the autoantibody repertoire in BAFF-Tg mice by microarray demonstrates a clear enrichment for RNA-associated autoantibodies. Strikingly, TACI deletion in BAFF-Tg mice results in the loss of these RNA-associated specificities, which correlated with a specific reduction in endocapillary, but not mesangial, IC deposits. Although, BAFF-dependent TACI signals may also promote antibody-independent B cell effector functions during the development of lupus nephritis, our combined findings strongly support a model in which a broad range of anti-nuclear autoantibodies, including RNA-associated specificities, can promote endocapillary IC formation and drive proliferative lupus nephritis.

Notably, several animal and human studies support the concept that RNA-associated autoantibodies promote the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. For example, in murine lupus models, deletion of Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7), an endosomal single-stranded RNA receptor, results in loss of RNA-associated autoantibodies and protection from IC glomerulonephritis. In contrast, deletion of TLR9, a DNA-binding receptor recognizing unmethylated CpG dinucleotides, resulted in a surprising increase in systemic inflammation despite loss of kinetoplast-reactive anti-dsDNA autoantibodies.18, 24 Additional support for a role for RNA-associated autoantibodies in murine lupus nephritis is provided by the pristine-induced lupus model, in which IL-12 deletion protects against IC glomerulonephritis without impacting anti-dsDNA titers. Although these IL-12 dependent effects were attributed to loss of TH1-biased inflammation, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) autoantibodies were strikingly reduced by IL-12 deletion and these events correlated with loss of capillary, but not mesangial, IC deposits45; observations mirroring the renal pathology of Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice. Consistent with these prior data, we now report that BAFF-Tg sera are enriched for RNA-associated autoantibodies, that deletion of either TACI or TLR7 results in loss of these autoantibody specificities, and that this change in the autoantibody repertoire correlates with lack of endocapillary immune deposits and protection from BAFF-driven renal disease.

In addition, human clinical data demonstrate that SLE patients with autoantibodies against Smith (Sm) antigen proteins, a component of the RNA-binding U-small nuclear riboprotein complex (U-snRNP), carry an increased risk for lupus nephritis, especially patients positive for both anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm autoantibodies.46, 47 Consistent with this idea, Mannik et al. tested the specificities of autoantibodies eluted from lupus nephritis glomeruli against a range of disease-associated autoantigens. In addition to dsDNA reactivity, autoantibodies against the RNA-associated antigens Sm, SSA and SSB were enriched within glomerular immune deposits, whereas control antibodies against tetanus toxoid and viral antigens exhibited no glomerular enrichment. Notably, the frequency of RNA-associated autoantibodies in glomerular extracts exceeded that of dsDNA, with DNA-reactive antibodies comprising <5% of eluted IgG.48 Although these findings do not prove pathogenicity of RNA-associated autoantibodies, the specific enrichment of these autoantibody specificities within glomeruli from patients with proliferative lupus nephritis lends support to a role in disease pathogenesis.

Importantly, the potential contribution of a broad spectrum of autoantibodies to lupus nephritis pathogenesis has therapeutic implications. For example, specifically targeting anti-dsDNA autoantibodies may not result in robust therapeutic efficacy in lupus nephritis. In keeping with this idea, Abetimus sodium, a tetrameric oligonucleotide conjugate that reduces anti-dsDNA titers, exhibited only modest efficacy in late stage clinical trials.49 Moreover, animal and human studies have demonstrated that anti-nuclear autoantibodies in SLE can be derived from either short-lived plasmablasts or long-lived plasma cells.50-52 Whereas anti-dsDNA autoantibodies often decrease following B cell depletion therapy, titers of RNA-associated autoantibodies are unaffected by Rituximab treatment, consistent with production by CD20neg long-lived plasma cells.53 These observations may explain the incomplete clinical benefit of B cell depletion therapy in lupus nephritis,54 and also emphasize the need to develop therapeutic strategies able to target the long-lived plasma cell compartment.

In summary, our study provides new insight into the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. By demonstrating that TACI deletion provides long-term protection from progressive BAFF-driven IC glomerulonephritis, our results highlight a potential therapeutic role for TACI inhibition in human lupus nephritis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

WT, BAFF-Tg,3 Taci-/-14, and Tlr7-/-55 mice (on the C57BL/6 background) and relevant murine crosses were bred and maintained in the specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility of Seattle Children's Research Institute (Seattle, WA). Experimental animals were either homozygous TACI-sufficient or -deficient, and heterozygous for expression of the BAFF transgene. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with Seattle Children's Research Institute IACUC approved protocols. Mice were sacrificed between 12 and 52 weeks of age. Both male and female mice were used in experimental studies.

Flow Cytometry

Single cell splenocyte suspensions were obtained and incubated with fluorescence-labeled antibodies for 20 minutes at 4°C, as previo usly described11. Data were collected on a LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc).

Antibodies

Anti-murine antibodies used in this study include: B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD138 (281-2), CD80 (16-10A1), from BD Biosciences; CD62L (MEL-14), CD11c (N418), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), CD11b (M1/70), GL7 (GL-7), from eBioscience; CD19 (ID3), CD44 (IM7), CD4 (RM4-4), IgM (MHM-88), CD21 (7E9), CD24 (M1/69), from BioLegend; FITC Goat Anti-Mouse IgG2c (SouthernBiotech).

Measurement of autoantibodies

For specific autoantibody ELISAs, 96 well Nunc-Immuno MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher) were pre-coated overnight at 4°C with calf thymus dsDNA (100ug/ml; Sigma-Aldrich D3664-5X2MG) or Sm/RNP (5ug/ml; Arotec Diagnostic Limited ATR01-10). For total serum antibodies, plates were pre-coated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-mouse IgM-, IgG-, IgG2c, IgG2b, IgA, IgG1 or IgG3 antibodies (1:500 dilution, SouthernBiotech) for 24 hours. Plates were blocked for 1 hour with 1% BSA in PBS prior to addition of diluted serum for 2 hours. Specific antibodies were detected using goat anti-mouse IgM-, IgG-, IgG2c, IgG2b, IgA, IgG1 or IgG3-HRP (1:2000 dilution; SouthernBiotech) and peroxidase reactions were developed using OptEIA TMB substrate (BD Biosciences) and stopped with sulfuric acid. Absorbance at 450nm was read using a SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) and data analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Autoantigen microarrays were performed at the UT Southwestern Medical Center Microarry Core Facility, Dallas, TX.19

For determination of dsDNA reactivity by kinetoplast staining, diluted serum (1:50) was added to fixed Crithidia luciliae slides (Kallestad® Crithidia luciliae Kit #31069, Bio-Rad). FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG served as the detection antibody and slides were counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescence images were obtained using Leica DM6000B microscope, Leica DFL300 FX camera, and Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence software at 63× using oil immersion objective with a constant exposure. Kinetoplast reactivity was defined by co-localization of DAPI-positive C. luciliae DNA and IgG FITC staining; with staining intensity scored from 0-3 by two independent observers blinded to genotype.

Quantification of albuminuria and serum BUN

Murine urine albumin was measured by indirect competitive ELISA (Albuwell M, Exocell) and urine creatinine measured using an enzymatic test kit (DZ072B-K, Diazyme). Serum urea nitrogen (BUN) was measured using a colorimetric method (DetectX Urea Nitrogen Detection kit, Arbor Assays). The protocols for all the kits were followed according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Serum BAFF quantification

BAFF levels were measured in sera from 6-month-old WT, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice using Mouse BAFF/BLyS/TNFSF 13B Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems) as per manufacturer's recommendation.

Histologic Analysis

Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of kidney were stained with periodic acid-Schiff and Jones silver methenamine. Images were acquired using a Nikon OptiPhot-2 microscope and a Canon Eos 5D Mark II camera. Selected tissues immersion fixed in ½ strength Karnovsky solution were processed, sectioned and examined by electron microscopy according to standard protocols. In cases examined by this technique, photographs were taken at 2,500×-25,000× magnification. ImageJ software was used to quantitate glomerular cell numbers and area. The severity of glomerular inflammation was scored by two independent blinded observers.

Immunofluorescence staining

Mouse kidneys were embedded in OCT compound and snap frozen over dry ice. 5μm sections were cut using Cryostat, mounted on slides and fixed in acetone for 20 mins at -200C. After the fixation, the slides were incubated with blocking buffer (PBS, 1% goat serum, 0.1% Tween-20, 1% BSA). The slides were subsequently stained with anti-FITC IgG, IgG2c and C3 in blocking buffer, washed and coverslipped with aqueous mounting media. Images were acquired using Leica microscope, Leica DFL300 FX camera and Leica software LAS X. Location of glomerular immune complex deposits was scored by a pathologist (C.E.A) blinded to genotype.

In vitro B cell stimulation assays

Splenic B cells were purified from WT, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice by CD43-microbead depletion (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.). Purified B cells were sorted using a FACSAria II sorter (BD Biosciences), with the following sort gates: CD19+B220+CD24intCD21int (FM). Sorted FM B cells were cultured in RPMI at 6.5 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate with or without R848 (10, 50 and 100 ng/mL) or CPG (0.1 and 1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 48 hours. Proliferation wa s evaluated by Cell Trace Violet (Invitrogen) dilution. Surface activation markers on stimulated B cells were evaluated by flow cytometry.

Real Time-PCR

Splenic B cells were purified from WT, BAFF-Tg and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg mice by CD43-microbead depletion (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.). Purified B cells were passed through QIA-Shredder (Qiagen) and stored in RLT buffer in -800C. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was converted using Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Real-Time PCR was performed on the cDNA using iTaq Universal Sybr Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) using the BioRad C1000 Thermal Cycler with mouse hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) as a control. Primers used were as follows: Hprt: 5′-TTGCTGACCTGCTGGATTACA-3′ (forward), 5′-CCCCGTTGACTGACTGATCATTACA-3′ (reverse), Tlr7: (forward) 5′-GTTCTTGACCTTGGCACTA-3′ (forward), 5′-CCGTGCATATTCATCGTA-3′ (reverse), Tlr9: 5′-CTGTACCAGGAGGGACAAGG-3′ (forward), 5′-CAGTTTGTCAGAGGGAGCCT-3′ (reverse).

Statistical Evaluation

P-values were calculated using the two-tailed Student's t test, the two-tailed Fisher's exact test, and the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: B cell activation in response to TLR ligands, (A, B) Proliferation of sorted WT (white), BAFF-Tg (red) and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (blue) FM B cells 48 hours after stimulation with TLR7 agonist R848 (A) or TLR9 agonist CPG (B). (C, D) Surface CD80 expression on activated B cells of indicated genotypes 48 hours after R848 (C) or CPG (D) stimulation. (E) Tlr7 and Tlr9 mRNA transcript in splenic B cells from BAFF-Tg (red) and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (blue) mice (expressed as fold change vs. WT). (A-E) Data representative of ≥2 experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; NS, not-significant; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for each ligand dose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank: Julia Procter, Jit Khim and Karen Sommer for assistance with murine studies and laboratory management; and Daryl Okamura for valuable suggestions and discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers: DP3-DK097672 (DJR), DP3-DK111802 (DJR), R01AI071163 (DJR), R21AI123818 (DJR) and K08AI112993 (SWJ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support provided by the Children's Guild Association Endowed Chair in Pediatric Immunology (DJR); by the Benaroya Family Gift Fund (DJR); by the ACR REF Rheumatology Career Development K Supplement (SWJ); by the Arthritis National Research Foundation (ANRF) Eng Tan Scholar Award (SWJ); and by the Arnold Lee Smith Endowed Professorship for Research Faculty Development (SWJ).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared that no competing financial conflict of interest exits.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mackay F, Schneider P. Cracking the BAFF code. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:491–502. doi: 10.1038/nri2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, et al. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1999;190:1697–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavin AL, Duong B, Skog P, et al. deltaBAFF, a splice isoform of BAFF, opposes full-length BAFF activity in vivo in transgenic mouse models. J Immunol. 2005;175:319–328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stohl W, Metyas S, Tan SM, et al. B lymphocyte stimulator overexpression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: longitudinal observations. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003;48:3475–3486. doi: 10.1002/art.11354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steri M, Orru V, Idda ML, et al. Overexpression of the Cytokine BAFF and Autoimmunity Risk. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;376:1615–1626. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:721–731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63:3918–3930. doi: 10.1002/art.30613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dooley MA, Houssiau F, Aranow C, et al. Effect of belimumab treatment on renal outcomes: results from the phase 3 belimumab clinical trials in patients with SLE. Lupus. 2013;22:63–72. doi: 10.1177/0961203312465781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson JS, Bixler SA, Qian F, et al. BAFF-R, a newly identified TNF receptor that specifically interacts with BAFF. Science. 2001;293:2108–2111. doi: 10.1126/science.1061965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figgett WA, Deliyanti D, Fairfax KA, et al. Deleting the BAFF receptor TACI protects against systemic lupus erythematosus without extensive reduction of B cell numbers. Journal of autoimmunity. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs HM, Thouvenel CD, Leach S, et al. Cutting Edge: BAFF Promotes Autoantibody Production via TACI-Dependent Activation of Transitional B Cells. J Immunol. 2016;196:3525–3531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy DD, Kujawa J, Wilson C, et al. Mice overexpressing BAFF develop a commensal flora-dependent, IgA-associated nephropathy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:3991–4002. doi: 10.1172/JCI45563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groom JR, Fletcher CA, Walters SN, et al. BAFF and MyD88 signals promote a lupuslike disease independent of T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1959–1971. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Bulow GU, van Deursen JM, Bram RJ. Regulation of the T-independent humoral response by TACI. Immunity. 2001;14:573–582. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310:1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson BL. Unraveling the immunopathogenesis of glomerular disease. Clin Immunol. 2016;169:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucisano Valim YM, Lachmann PJ. The effect of antibody isotype and antigenic epitope density on the complement-fixing activity of immune complexes: a systematic study using chimaeric anti-NIP antibodies with human Fc regions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb08115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson SW, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, et al. Opposing impact of B cell-intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 signals on autoantibody repertoire and systemic inflammation. J Immunol. 2014;192:4525–4532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li QZ, Zhou J, Wandstrat AE, et al. Protein array autoantibody profiles for insights into systemic lupus erythematosus and incomplete lupus syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:60–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isenberg DA, Manson JJ, Ehrenstein MR, et al. Fifty years of anti-ds DNA antibodies: are we approaching journey's end? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1052–1056. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker-Herman S, Meyer-Bahlburg A, Schwartz MA, et al. WASp-deficient B cells play a critical, cell-intrinsic role in triggering autoimmunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:2033–2042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson SW, Jacobs HM, Arkatkar T, et al. B cell IFN-gamma receptor signaling promotes autoimmune germinal centers via cell-intrinsic induction of BCL-6. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2016;213:733–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isenberg DA, Dudeney C, Williams W, et al. Measurement of anti-DNA antibodies: a reappraisal using five different methods. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1987;46:448–456. doi: 10.1136/ard.46.6.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawlings DJ, Schwartz MA, Jackson SW, et al. Integration of B cell responses through Toll-like receptors and antigen receptors. Nature reviews Immunology. 2012;12:282–294. doi: 10.1038/nri3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rawlings DJ, Metzler G, Wray-Dutra M, et al. Altered B cell signalling in autoimmunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2017;17:421–436. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shlomchik MJ. Activating systemic autoimmunity: B's, T's, and tolls. Current opinion in immunology. 2009;21:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figgett WA, Deliyanti D, Fairfax KA, et al. Deleting the BAFF receptor TACI protects against systemic lupus erythematosus without extensive reduction of B cell numbers. J Autoimmun. 2015;61:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1124978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deane JA, Pisitkun P, Barrett RS, et al. Control of toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, et al. Evolution of disease burden over five years in a multicenter inception systemic lupus erythematosus cohort. Arthritis care & research. 2012;64:132–137. doi: 10.1002/acr.20648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thien M, Phan TG, Gardam S, et al. Excess BAFF rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion and allows them to enter forbidden follicular and marginal zone niches. Immunity. 2004;20:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesley R, Xu Y, Kalled SL, et al. Reduced competitiveness of autoantigen-engaged B cells due to increased dependence on BAFF. Immunity. 2004;20:441–453. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hondowicz BD, Alexander ST, Quinn WJ, 3rd, et al. The role of BLyS/BLyS receptors in anti-chromatin B cell regulation. International immunology. 2007;19:465–475. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treml LS, Carlesso G, Hoek KL, et al. TLR stimulation modifies BLyS receptor expression in follicular and marginal zone B cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7531–7539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mantchev GT, Cortesao CS, Rebrovich M, et al. TACI is required for efficient plasma cell differentiation in response to T-independent type 2 antigens. J Immunol. 2007;179:2282–2288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Carmona Y, Cols M, Ting AT, et al. Differential induction of plasma cells by isoforms of human TACI. Blood. 2015;125:1749–1758. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-575845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozcan E, Garibyan L, Lee JJ, et al. Transmembrane activator, calcium modulator, and cyclophilin ligand interactor drives plasma cell differentiation in LPS-activated B cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1277–1286 e1275. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nundel K, Green NM, Shaffer AL, et al. Cell-intrinsic expression of TLR9 in autoreactive B cells constrains BCR/TLR7-dependent responses. J Immunol. 2015;194:2504–2512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goenka R, Matthews AH, Zhang B, et al. Local BLyS production by T follicular cells mediates retention of high affinity B cells during affinity maturation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:45–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahman ZS, Rao SP, Kalled SL, et al. Normal induction but attenuated progression of germinal center responses in BAFF and BAFF-R signaling-deficient mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198:1157–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ter Borg EJ, Horst G, Hummel EJ, et al. Measurement of increases in anti-double-stranded DNA antibody levels as a predictor of disease exacerbation in systemic lupus erythematosus. A long-term, prospective study Arthritis and rheumatism. 1990;33:634–643. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koffler D, Schur PH, Kunkel HG. Immunological studies concerning the nephritis of systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1967;126:607–624. doi: 10.1084/jem.126.4.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ehrenstein MR, Katz DR, Griffiths MH, et al. Human IgG anti-DNA antibodies deposit in kidneys and induce proteinuria in SCID mice. Kidney Int. 1995;48:705–711. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calvani N, Satoh M, Croker BP, et al. Nephritogenic autoantibodies but absence of nephritis in Il-12p35-deficient mice with pristane-induced lupus. Kidney Int. 2003;64:897–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alba P, Bento L, Cuadrado MJ, et al. Anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm antibodies, and the lupus anticoagulant: significant factors associated with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:556–560. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.6.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janwityanuchit S, Verasertniyom O, Vanichapuntu M, et al. Anti-Sm: its predictive value in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 1993;12:350–353. doi: 10.1007/BF02231577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mannik M, Merrill CE, Stamps LD, et al. Multiple autoantibodies form the glomerular immune deposits in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1495–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cardiel MH, Tumlin JA, Furie RA, et al. Abetimus sodium for renal flare in systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a randomized, controlled phase III trial. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;58:2470–2480. doi: 10.1002/art.23673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoyer BF, Moser K, Hauser AE, et al. Short-lived plasmablasts and long-lived plasma cells contribute to chronic humoral autoimmunity in NZB/W mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;199:1577–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang H, Benoist C, Mathis D. Rituximab specifically depletes short-lived autoreactive plasma cells in a mouse model of inflammatory arthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:4658–4663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001074107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahevas M, Michel M, Weill JC, et al. Long-lived plasma cells in autoimmunity: lessons from B-cell depleting therapy. Front Immunol. 2013;4:494. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cambridge G, Leandro MJ, Teodorescu M, et al. B cell depletion therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus: effect on autoantibody and antimicrobial antibody profiles. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2006;54:3612–3622. doi: 10.1002/art.22211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: the Lupus Nephritis Assessment with Rituximab study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64:1215–1226. doi: 10.1002/art.34359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:5598–5603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: B cell activation in response to TLR ligands, (A, B) Proliferation of sorted WT (white), BAFF-Tg (red) and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (blue) FM B cells 48 hours after stimulation with TLR7 agonist R848 (A) or TLR9 agonist CPG (B). (C, D) Surface CD80 expression on activated B cells of indicated genotypes 48 hours after R848 (C) or CPG (D) stimulation. (E) Tlr7 and Tlr9 mRNA transcript in splenic B cells from BAFF-Tg (red) and Taci-/-.BAFF-Tg (blue) mice (expressed as fold change vs. WT). (A-E) Data representative of ≥2 experiments. Error bars indicate SEM. *, P<0.05, **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; NS, not-significant; by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test for each ligand dose.