Abstract

Introduction

To develop and evaluate a technique of 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance (MR) guided laser ablation based on 3-dimentional mapping biopsy (3DMB) for low risk prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the institutional review board and was the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. The prospective study was performed on seven 3DMB proven low risk prostate cancer patients. In the first phase of the procedure the patient's prostate was aligned to a position concordant with prior 3DMB using the transperineal grid and fiduciary golden marker coordinates. In the second phase ablation was performed using MR thermometry to determine the ablation endpoint and lesion coverage. Immediately after treatment dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging was done. Prostate-specific antigen testing was performed 3 and 12 months after the treatment and compared by ANOVA test. A follow up biopsy was done one year following ablation.

Results

The entire procedure took less than 2 hours and all patients tolerated the procedure well. There was a significant difference in prostate-specific antigen value before and 3 months after the treatment (p = 0.005). Four out of 6 patients had positive follow up biopsy for cancer.

Conclusion

This study verifies the feasibility and safety of treating low risk prostate cancer with laser therapy guided by 3.0T MR imaging based on 3DMB.

Key Words: Prostate cancer, Focal therapy, MRI, Ultrasound, Prostate biopsy

Introduction

With current trends of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening and the lowered PSA threshold for biopsy, contemporary statistics show that 45% of tumors are classified as very low risk for men 55 years and younger, with 85% of these tumors showing favorable pathology [1]. It can be difficult to predict which cancers have the risk of progression and which will become life threatening. Radical whole-gland treatment carries potential risks for incapacitating urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, and for these reasons is often viewed as overtreatment in the context of low risk prostate cancer (PCa) [2]. For these cancers, focal therapy appears to be gaining acceptance for a better balance between cancer control and side effects.

Focal therapy has the goal of targeting the cancerous foci of the prostate gland with minimal collateral damage to surrounding tissue [3]. The success of the focal therapy relies on the accurate staging of the disease and exact localization of the tumor. In this effort, a template-guided transperineal 3-dimentional mapping biopsy (3DMB) was developed which demonstrated a significant improvement in evaluating the size, number and location of cancer foci compared to transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy [4, 5, 6].

Focal laser ablation (FLA) carries the potential of being an accurate, highly guided, repeatable approach that induces minimal damage outside the targeted ablation zone with pinpoint accuracy. One of the main advantages in using focal laser ablation for PCa treatment is that lasers are highly magnetic resonance (MR) compatible. MR is capable of monitoring temperature change using thermal imaging capabilities, which makes it an ideal imaging modality for real-time assessment of thermal ablation in situ [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12].

The purpose of our study was to develop and evaluate a technique of 3.0 Tesla (T) MR guided laser ablation based on 3DMB for low risk PCa.

Materials and Methods

FLA was offered to patients who attended the clinic between August 2009 and April 2011. Patients who elected the option of focal laser ablation were included in the study on a rolling-admission basis. Inclusion criteria consists of TRUS biopsy defined early state organ-confined T1c prostate cancer with a Gleason score of 3 + 3 = 6, less than 4 foci of cancer, and PSA < 10 ng/ml as according to D'Amico low risk criteria [13]. Patients meeting these criteria underwent 3DMB to more accurately stage and grade their cancer. The 3DMB procedure has been previously described [14]. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the hospital and was the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant. From August 2009 to April 2011, seven patients were included in this study. Patients' clinical and biopsy information are listed in table 1. All patients elected to undergo 3DMB in order to exclude or confirm stage, grade, and location of cancer foci. Prostate volume by TRUS in these patients ranged from 30 to 34 grams. After thorough discussion with the urologist, these patients made the informed decision to be treated by MR guided focal laser ablation and were consented accordingly. Treatment was performed on average 72 days after 3DMB. The regions of interest for ablation were biopsy proven low grade cancer foci detected by 3DMB. The entire process from diagnosis to ablation took one of 2 routes which are summarized below.

Table 1.

Biopsy intake information and follow-up biopsy results

| Subject | TRUS prior to FLA (positive cores/total cores) | 3DMB prior to FLA (positive cores/ total cores); Max core involvement | PSA prior to 3DMB (ng/ml) | Follow-up biopsy at 1 year; Max core involvement | Correlation with ablation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1/12 (right) | 1/51 (right) 30% |

4.32 | 1/12 60% |

same side as ablation |

| 2 | 1/9 (left) | 4/50 (bilateral) 5% |

5.6 | 2/12 30% |

same side as ablation |

| 3 | 0/12 | 1/36 (right) < 5% |

3.96 | 0/12 0% |

benign findings |

| 4 | 1/12 (right) | 5/53 (bilateral) 25% |

5.22 | 1/12 5% |

same side as ablation |

| 5 | 2/13 (right) | 2/66 (right) 50% |

4.33 | lost to follow-up | lost to follow-up |

| 6 | 0/12 | 5/42 (bilateral) 35% |

5.0 | 1/37 (3DMB) 10% |

same side as ablation |

| 7 | 0/12 | 1/53 (right) < 5% |

5.43 | 0/12 0% |

benign findings |

TRUS = Transrectal ultrasound; PSA = prostate specific antigen; 3DMB = 3-dimentional mapping biopsy; and FLA = focal laser ablation.

The First Phase is for Diagnosis and Staging of Prostate Cancer

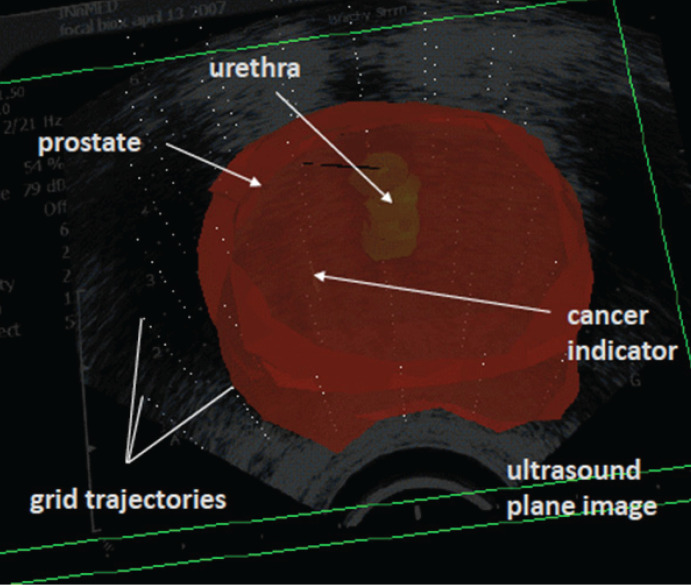

Transperineal 3DMB. Mapping biopsy consisted of systematic transperineal template-guided prostate biopsy in a Trendelenburg position with multiple core samples (36 to 66 cores) per patient depending on the size of the prostate gland [5]. Each core specimen from 3DMB of prostate is labeled based on the transperineal grid template co-ordinates by urologist at the time of biopsy (fig. 1). Fiducial markers are inserted in the prostate for the purposes of alignment in future procedures. Each core from 3DMB was independently analyzed and reported by a uropathologist. Positive biopsy data for cancer were compiled onto 3D models of the prostate gland utilizing proprietary software called ProVIEW (Applied Coherent Technology, Herndon, Virginia).

Fig. 1.

3DMB interface. Sample oblique view of a 3-dimensional reconstructed prostate demonstrating Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 cancer in 1 core on the left.

The results of 3DMB are compared to the original TRUS biopsy and the decision is finalized to proceed with focal laser ablation. The day before the focal laser ablation, the patient undergoes a multiparametric 3.0 T prostate MR imaging (MRI).

3.0 T MR Examination. 3.0 T MRI (3.0T GE HDX Signa, GE Medical Systems) was performed to localize the biopsy positive cancer foci in the prostate gland and to exclude extra capsular tumor extension.

Preprocedure MRI study was performed on a 3.0 T scanner (GE Signa HDxt - Fairfield, CT, USA) utilizing an endorectal coil (Medrad Prostate eCoil, Warrendale, PA, USA) and 8 channel pelvis phased array surface coil. MRI protocol included large field-of-view images of the pelvis, small field of view tri-planar high resolution T2-weighted, diffusion weighted images with apparent diffusion coefficient maps, and dynamic post contrast sequences.

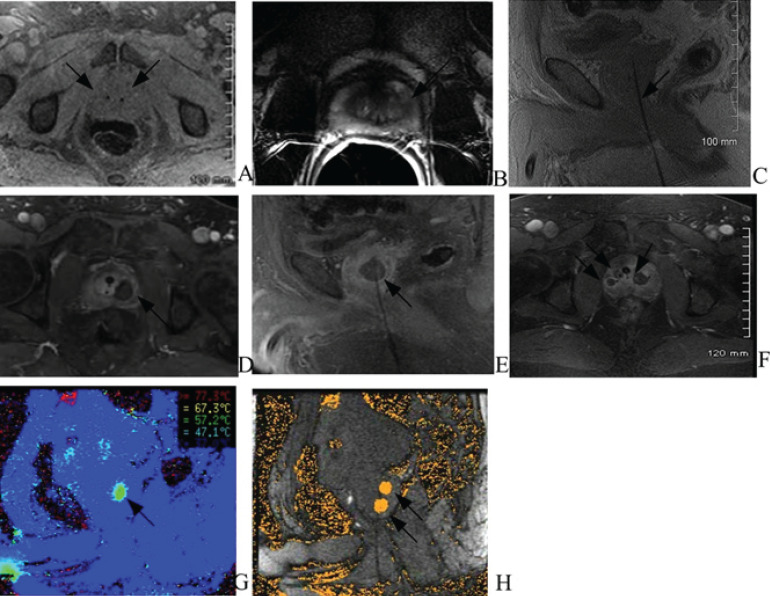

MRI images are reviewed by experienced radiologist and then compared with pathology results to localize the cancer foci detected by 3DMB. The ultrasound/MRI fusion was not performed in patients 1–4 as the fusion technique was not available to us at that time. In the last consecutive 3 patients we were able to fuse 3D imaging from the 3DMB ultrasound and 3D rendering of the MRI imaging preoperatively and match the cancer locations from both imaging modalities (fig. 2, 3). The software used was in development during this period (Proview Software, Bcsi Inc, 721 N Tejon Street 200 Colorado Springs, CO 80903 in association with department of surgery UCSOM). MRI scan parameters are listed in table 2. While growing evidence exists that Computer Aided Evaluation systems may improve the workflow, it is not required to interpret multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) and was not used to process the dynamic post contrast images in this study.

Fig. 2.

Combined ultrasound, and biopsy data in one graphical interface.

Fig. 3.

MR-US 3D fusion software. lllustrates the matching technique for the pathologically detected positive biopsy on transperinneal biopsy and the suspicious MRI focus. Two US generated image slices are highlighted in this figure, with each dot representing a biopsy coordinate and the 3D prostate reconstruction outlined in red.

Table 2.

MRI scan parameters

| Matrix | ETL | TR (ms) | TE (ms) | Gap (mm) | Slice (mm) | FOV (mm) | Flip angle (degs) | b values | Post-contrast acquisition start time (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2-weighted axial | 384 × 192 | 17 | 2617 | 135 | 0 | 3 | 160 | 90 | ||

| T2-weighted sagittal | 384 × 256 | 17 | 3467 | 115 | 0 | 3 | 160 | 90 | ||

| T2-weighted coronal | 384 × 256 | 17 | 5050 | 115 | 0 | 3 | 160 | 90 | ||

| Diffusion axial | 96 × 128 | 1 | 4000 | 72–89 | 0 | 3 | 200 | 90 | 0, 600, 1000 | |

| T1-weighted fat sat pre/post contrast axial | 256 × 192 | 1 | 5.68 | 2.1 | 1.5 overlap | 3 | 240 | 10 | 10, 38, 115, 230 |

ETL = Echo train length; TE = echo time; and FOV = field of view.

The Second Phase is for Targeting and Ablation of Cancer

Targeting of the Cancer Foci. Localization and targeting of prostate cancer foci is done in the day surgery operating suite under general anesthesia. Patients were placed in lithotomy position and a urethral catheter was introduced. The patient's prostate was aligned to a position concordant with prior 3DMB using the transperineal grid and fiduciary golden marker coordinates placed at the time of 3DMB (fig. 4). Following the selection of the needle path, the laser shelter (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, Illinois) with an MR-compatible titanium trocar was inserted transperineally in the prostate through the template hole that yielded cancer foci on 3DMB.

Fig. 4.

Placement with US guidance using the step technique and guided by the rendered 3D US imaging.

Advancement of the shelter was monitored with TRUS in realtime 3D imaging using 3DART8838 flex focus ultrasound probe (BK medical, Denmark). After introducing the trocar, the metal insert was removed and the sheath was affixed to the skin. A laser applicator with cylindrically diffusing tip attached (using prolene 3.0) to a 980-nm diode laser (Visualase Inc, Houston, TX, USA) was introduced through the sheath into the area of interest and was checked on biplane ultrasound to be in the correct place.

Real Time 3.0 T MR Guided Laser Ablation. The patient was then transferred to MRI suit for real time MR guided laser ablation. In the supine position, sagittal spoil gradient-echo T1 weighted MRI of the prostate is obtained to localize and confirm the position of the laser probe in the prostate gland. Real time interstitial laser ablation is performed under MR guidance with continuously updated MR temperature mapping using the MR thermometry software and Visualase protocol (Visualase, Inc, Houston, TX, USA). The induction of high amounts of energy from the laser induces irreversible cell injury and subsequent coagulative necrosis at temperatures ≥ 50 °C at the application zone. The area surrounding the ablative site undergoes a heat-sink effect wherein high temperatures are dissipated, contributing to the containment of the ablation zone. The mechanism of hyperthermic ablation is further described in Chu et al. [15].

Ablation and post procedure imaging on average takes between 1 to 2 hours, whereas the laser ablation itself takes 90 seconds per foci. The amount of foci ablated was dependent on 3DMB findings, but on average there were 2 to 3 foci ablated per patient.

Immediate post procedure MRI of the prostate is performed with and without intravenous contrast using small field of view 3D gradient echo sequence in axial and sagittal planes to analyze the ablation sites.

Patients are discharged home the same day. Urethral catheter was not necessary in 6 of the 7 patients. Patients were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics for 48 hours after the procedure.

Follow up Evaluation

To evaluate treatment effect, prostate biopsies were taken one year following treatment. In addition, PSA was measured before treatment, 3 months after treatment, and at one year follow up. To evaluate the subjective experience for the patients, both the Sexual Health Inventory for Men and the American Urological Association Symptom Score were administered before treatment and 3 months after treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The ANOVA test was used to assess the difference between paired measurements of PSA level 3 and 12 months and those at baseline. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

3.0 T MR Examination

Two fiducial seeds were noted within the central gland (fig. 5A). In all 7 patients the capsule was intact and there was no evidence of extracapsular tumor extension. There were a total of 19 positive lesions detected by 3DMB in these 7 patients. Eight lesions were seen on MRI and correlated to the biopsy proven prostate cancer. Out of these 8 lesions, 7 lesions were located in the peripheral zone and 1 in the junction of peripheral zone and central gland (fig. 5B). The other 11 lesions found on 3DMB were located in the transitional zone of the central gland and could not be prospectively differentiated from benign prostatic hyperplasia nodules by MRI.

Fig. 5.

MRI images demonstrating FLA sequence. Images in 57 year old male without family history of prostate cancer with PSA of 5.0ng/ml and bilateral Gleason 3 + 3 cancer (two on right lateral and three on the left lateral gland). A T1 fatsat axial noncontrast MRI prior to the laser treatment demonstrates two fiducial seeds (arrow) within the central gland. B Pretreatment diagnostic MRI demonstrates T2 dark signal (arrow) in the left peripheral zone compatible with history of Gleason 6 carcinoma. C Spoiled gradient T1 weighted MR imaging in the sagittal plane confirms the laser probe (arrow) in the prostate before the ablation. D Post-procedure MRI with contrast in axial plane immediately after the laser treatment shows an area of nonenhancement at the site of ablation (arrow) that correlates with positive MRI finding seen in image B. E Post-procedure MRI in the same patient with contrast shows an area of non-enhancement at the same site of ablation (arrow) with laser probe in sagittal plane. F Post-procedure MRI in axial plane with contrast demonstrates three separate areas of ablation (arrows) at the site of the laser probes in the same patient. G Real time MR thermography image in sagittal plane shows temperature map (arrow) in target area. H MR thermography image in sagittal plane shows two areas of ablations (arrows).

T1 spoiled gradient echo sagittal plane MRI sequence imaging confirmed the placement of the laser probe in the prostate (fig. 5C). One to 3 probes were used in the prostate depending on the number of cancer foci in each patient (fig. 5F). The quality of temperature mapping allowed for accurate measurements within the prostate. Both temperature and thermal damage maps provide real time information about the ablation zone in all patients (fig. 5G, H). All patients tolerated the procedure well without immediate complication (bleeding, infection and pain). Real time MR guided laser ablation procedure time varied from 45 to 90 minutes depending on the number of ablations.

Patients reported some blood in urine from 24–48 hours. One patient had urinary retention 3 weeks after the procedure and required a Foley catheter for 3 days. He recovered without further complications. The other 6 patients had no complications from the procedure during the one year follow up.

Postprocedure 3.0 T MR Examination

A contrast-enhanced MRI scan done immediately following treatment showed good correlation with the thermal damage calculations of the MRI-thermometry software and non enhancement surrounding the probe (fig. 5E, G).

Patient Reported Measures and PSA

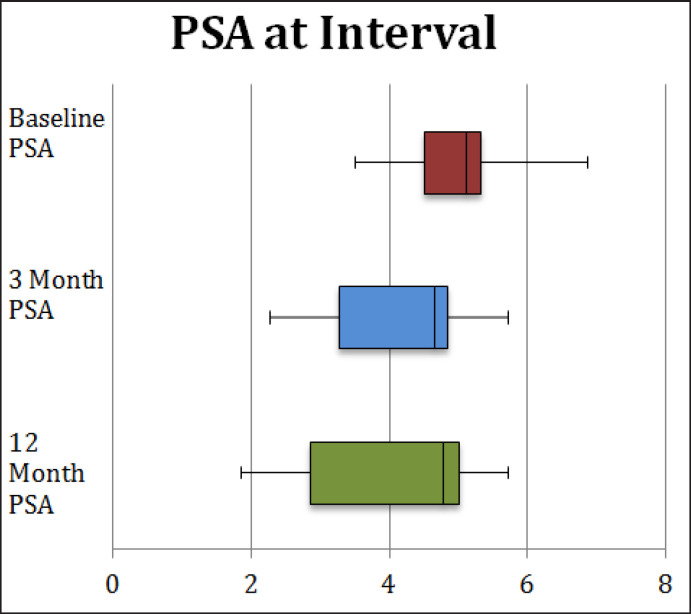

The mean PSA level before treatment, 3 months and 12 months after treatment was 5.05 ± 0.89 ng/ml, 4.18 ± 1.12 ng/ml and 3.94 ± 1.68 ng/ml, respectively (table 3, fig. 6). There was a significant difference in PSA value before and 3 months after the treatment (p = 0.005). There was no significant difference in PSA value before and 12 months after the treatment (p = 0.149). The results of the American Urological Association Symptom Score and Sexual Health Inventory for Men are reported in table 3 and are purely observational as lack of compliance made statistical analysis impractical.

Table 3.

AUA, SHIM, and PSA

| Age (year) | AUA-SS pre-FLA | AUA-SS post-FLA (3 months) | SHIM pre-FLA | SHIM post FLA (3 months) | PSA at time of FLA | PSA 3 month follow-up | PSA 12 month follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | 0/35 | 0/35 | 24/25 | 22/25 | 4.4 | 4.86 | 4.98 |

| 2 | 58 | × | × | × | × | 5.1 | 2.7 | 3.82 |

| 3 | 61 | × | × | × | × | 4.6 | 5.71 | 5.71 |

| 4 | 56 | 10/35 | 2/25 | × | 20/25 | 5.22 | 4.82 | 1.36 |

| 5 | 69 | × | 3/35 | × | 23/25 | 3.79 | 3.62 | 4.77 |

| 6 | 58 | 0/35 | 0/35 | 24/25 | 22/25 | 6.86 | 4.65 | 5.04 |

| 7 | 66 | × | × | × | × | 5.39 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

SHIM = Sexual Health Inventory for Men; AUA = American Urological Association Symptom Score.

Fig. 6.

PSA values at respective time intervals.

Follow up Biopsy

Five of 7 patients had 12 core TRUS biopsy 1 year after laser ablation, 1 patient had 3DMB and 1 patient was lost to follow up. Two patients had benign findings and 4 patients were found to have T1c cancer on the same side of the prostate as the ablated foci (table 1).

Discussion and Conclusion

MRI guided laser ablation in the area for prostate cancer has been previously reported by 4 studies [16, 17, 18], all of which targeted the lesions by MRI, however prostate cancer is multifocal, and some early and low grade cancer may not have specific MRI characteristics. Furthermore, MRI has limitations when evaluating central gland disease for transitional and central zone cancer [19]. In our study, 11 lesions found on 3DMB were located in the central gland and could not be prospectively differentiated from benign prostatic hyperplasia nodules by the MRI.

Our procedure differs in that we used a transperineal grid, golden fiducial markers and ultrasound/MRI fusion (in 3 patients) to target 3DMB proven prostate cancer foci. We believe this provides for a more accurate approach for targeting of cancer foci, both visualized and not visualized by MRI.

In our study, the targeting and ablation of the lesion in the MRI suite took about 30 minutes, suggesting a faster procedural time than what has been previously reported [16]. Less time in the MRI suite makes this expensive modality available to other patient examinations in a timely manner.

PSA levels were reduced and significantly lower 3 months after the ablation compared to the baseline PSA prior to treatment, however there was no significant difference between the baseline PSA and PSA one year after the ablation [3, 5]. One year after treatment we still find cancer foci on the same side of the prostate as the ablation and we believe this may be due to four possible reasons. First, prostate cancer is multifocal so the new foci may be due to false negatives on pretreatment biopsy. Second, during the pre-treatment biopsy the lesions may be too small to detect but grew during the one-year time interval between treatment and follow up. Third, we used a transperineal grid and fiducial markers to target the 3DMB based histologically proven prostate cancer foci in patients 1–4. Ultrasound/MR fusion was added to assist with targeting of cancer foci visualized by MRI in patients 5–7, however, this technique was at a primitive stage at that time. Although we tried to overlay tumors as accurately as possible, there is still the possibility of missing the target lesion. Fourth, the effects of laser ablation may not be permanent.

As laser therapy can be done on an outpatient basis, it takes less time for patients to heal after laser surgery, and they are less likely to get infections. In our study, patients had no severe complications from the procedure during the one-year follow up.

This is potentially the first focal laser ablation technique to be compatible with 3.0 T MRI based on 3DMB screening. The present study demonstrated that the temperature mapping was possible at 3.0 T field strength, which offers greater spatial and temporal resolution with improved prostate imaging compared with the 1.5 T field strength. This study also explores the potential of the ultrasound/MR fusion technology for prostate biopsy and intervention.

Advantages to this methodology included shorter procedural time in the MRI suite and targeting based on biopsy proven cancer locations. Using this method, targeting of biopsy proven low-grade cancer foci not visualized by MRI was also possible.

Our study was prospective and the sample size was small. This study did not utilize a pre-existing follow-up schedule as the technique is still novel. We did 3DMB with 36–66 cores and no matter how expertly done, this procedure may carry a risk of bleeding and urinary retention. While details provided in TRUS biopsy reports seem to indicate that cancer foci found on follow up differed in location from those found during staging biopsy (specifically in regards to basal versus apical locations), there is a well-documented lack of positional accuracy in the TRUS biopsy procedure, making it difficult to determine whether the tumors found in 4 out of 6 patients with follow up data is due to recurrent, new or residual tumor tissue. These results suggest that a wider ablation field may be necessary to capture residual cancer foci.

This study serves to verify the feasibility and safety of treating low risk prostate cancer with laser therapy guided by 3.0 T MRI based on 3DMB. Patient selection in this study was aimed towards a definition of low-risk prostate cancer which at the same times meets commonly held definitions of clinically insignificant cancer [20]. It is impossible to know which cancers will or will not progress with current diagnostic methods, however it is currently accepted that low-risk prostate cancer should not be treated with traditional therapies due to high side effect profile and questionable impact on mortality. Focal therapy is an emerging technology that may serve to prevent low-risk prostate cancer from becoming aggressive without inducing side-effects common to traditional therapies. It should be iterated that current recommendations and the momentum of focal therapy does not support treatment of such tumors but rather treatment of intermediate risk cancers. Results from a consensus meeting on focal therapy now demonstrate an increased focus on treating intermediate-risk cancers and treatment of the index lesion, and while agreement with a lower level of consensus was reached on treatment of low-risk cancers, experts strongly agreed that well-characterized low-risk cancers were best served by active surveillance [20]. Prospective studies with larger samples are needed that include long term follow up for treatment of more clinically significant cancers to determine efficacy and efficiency of this technique.

Conflict of Interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work. There was no extramural funding. An FDA approved device was utilized and funding was accomplished by a mix between insurance-approved procedures or patients paid out of pocket.

References

- 1.Kim J, Ebertowski J, Janiga M, Arzola J, Gillespie G, Fountain M, Soderdahl D, Can-by-Hagino E, Elsamanoudi S, Gurski J, Davis JW, Parker PA, Boyd DD. Many young men with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screen-detected prostate cancers may be candidates for active surveillance. BJU Int. 2013;111:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Sullivan KF, Crawford ED. Targeted focal therapy for prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Ther Adv Urol. 2009;1:149–159. doi: 10.1177/1756287209338708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barqawi AB, Stoimenova D, Krughoff K, Eid K, O'Donnell C, Phillips JM, Crawford ED. Targeted focal therapy in the management of organ confined prostate cancer. J Urol. 2014;192:749–753. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barqawi AB, Krughoff KJ, Eid K. Current challenges in prostate cancer management and the rationale behind targeted focal therapy. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:862639. doi: 10.1155/2012/862639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barqawi AB, Rove KO, Gholizadeh S, O'Donnell CI, Koul H, Crawford ED. The role of 3-dimensional mapping biopsy in decision making for treatment of apparent early stage prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford ED, Rove KO, Barqawi AB, Maroni PD, Werahera PN, Baer CA, Koul HK, Rove CA, Lucia MS, La Rosa FG. Clinical-pathologic correlation between transperineal mapping biopsies of the prostate and three-dimensional reconstruction of prostatectomy specimens. Prostate. 2013;73:778–787. doi: 10.1002/pros.22622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed HU, Hu Y, Carter T, Arumainayagam N, Lecornet E, Freeman A, Hawkes D, Barratt DC, Emberton M. Characterizing clinically significant prostate cancer using template prostate mapping biopsy. J Urol. 2011;186:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taira AV, Merrick GS, Galbreath RW, An dreini H, Taubenslag W, Curtis R, Butler WM, Adamovich E, Wallner KE. Performance of transperineal template-guided mapping biopsy in detecting prostate cancer in the initial and repeat biopsy setting. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;13:71–77. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barzell WE, Melamed MR. Appropriate patient selection in the focal treatment of prostate cancer: the role of transperineal 3-dimensional pathologic mapping of the prostate—a 4-year experience. Urology. 2007;70((6 suppl)):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel V, Merrick GS, Allen ZA, Andreini H, Taubenslag W, Singh S, Butler WM, Adamovich E, Bittner N. The incidence of transition zone prostate cancer diagnosed by transperineal template-guided mapping biopsy: implications for treatment planning. Urology. 2011;77:1148–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stafford RJ, Shetty A, Elliott AM, Klumpp SA, McNichols RJ, Gowda A, Hazle JD, Ward JF. Magnetic resonance guided, focal laser induced interstitial thermal therapy in a canine prostate model. J Urol. 2010;184:1514–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodrum DA, Gorny KR, Mynderse LA, Amrami KK, Felmlee JP, Bjarnason H, Garcia-Medina OI, McNichols RJ, Atwell TD, Callstrom MR. Feasibility of 3.0T magnetic resonance imaging-guided laser ablation of a cadaveric prostate. Urology. 2010;75:1514. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.059. e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Weinstein M, Tomaszewski JE, Schultz D, Rhude M, Rocha S, Wein A, Richie JP. Predicting prostate specific antigen outcome preoperatively in the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol. 2001;166:2185–2188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barqawi AB, Rove KO, Gholizadeh S, et al. The role of 3-dimensional mapping biopsy in decision making for treatment of apparent early stage prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu KF, Dupuy DE. Thermal ablation of tumours: biological mecahnisms and advances in therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:199–208. doi: 10.1038/nrc3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oto A, Sethi I, Karczmar G, McNichols R, Ivancevic MK, Stadler WM, Watson S, Eggener S. MR imaging-guided focal laser ablation for prostate cancer: phase I trial. Radiology. 2013;267:932–940. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raz O, Haider MA, Davidson SR, Lindner U, Hlasny E, Weersink R, Gertner MR, Kucharczyk W, McCluskey SA, Trachtenberg J. Real-time magnetic resonance imaging-guided focal laser therapy in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2010;58:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodrum DA, Mynderse LA, Gorny KR, Amrami KK, McNichols RJ, Callstrom MR. 3.0T MR-guided laser ablation of a prostate cancer recurrence in the postsurgical prostate bed. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:929–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alonzi R, Padhani AR, Allen C. Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in prostate cancer. Eur J Radiology. 2007;63:335–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ploussard G, Epstein JI, Montironi R, Carroll PR, Wirth M, Grimm MO, Bjartell AS, Montorsi F, Freedland SJ, Erbersdobler A, van der Kwast TH. The contemporary concept of significant versus insignificant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donaldson IA, Alonzi R, Barratt D, Barret E, Berge V, Bott S, Bottomley D, Eggener S, Ehdaie B, Emberton M, Hindley R, Leslie T, Miners A, McCartan N, Moore CM, Pinto P, Polascik TJ, Simmons L, van der Meulen J, Villers A, Willis S, Ahmed HU. Focal therapy: patients, interventions, and outcomes-a report from a consensus meeting. Eur Urol. 2015;67:771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]