Serovars within the species Salmonella enterica are some of the most common food and water-borne pathogens worldwide.

Serovars within the species Salmonella enterica are some of the most common food and water-borne pathogens worldwide.

Abstract

Serovars within the species Salmonella enterica are some of the most common food and water-borne pathogens worldwide. Some S. enterica serovars have shown a remarkable ability to persist both inside and outside the human body. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi can cause chronic, asymptomatic infection of the human gallbladder. This organism's ability to survive inside the gallbladder centers around its ability to form biofilms on gallstone surfaces. Currently, chronic carriage of S. Typhi is treated by invasive methods, which are not well suited to areas where Salmonella carriage is prevalent. Herein, we report 2-aminobenzimidazoles that inhibit S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (a surrogate for S. Typhi) biofilm formation in low micromolar concentrations. Modifications to the head, tail, and linker regions of the original hit compound elucidated new, more effective analogues that inhibit S. Typhimurium biofilm formation while being non-toxic to planktonic bacterial growth.

Salmonella species are a frequent cause of food and water borne illness worldwide. They can cause a variety of disease syndromes, and are normally grouped into typhoidal and non-typhoidal species. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi is the causative agent of enteric fever and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhiumiurum is typically associated with intestinal distress, or salmonellosis.1 Typhoidal and non-typhoidal strains of Salmonella have shown a remarkable ability to persist in a variety of environments, including harsh environments within the human body. One of these survival strategies centers around the ability of Salmonella to form biofilms on gallstones.2 Colonization of gallstones can then lead to chronic carriage of S. Typhi, which allows for the dissemination of Salmonella through fecal shedding. Biofilms can be up to 1000-fold more resistant to antibiotic treatment than their planktonic counterparts, rendering typical antibiotic treatment regimens ineffective at eradicating chronic carriage of Salmonella.3–5 Presently, chronic carriage of Salmonella is treated by invasive methods, which are not well suited to areas where Salmonella is prevalent.6 New treatment options for chronic carriage of Salmonella are needed, and compounds that perturb Salmonella biofilms could be a viable treatment option.

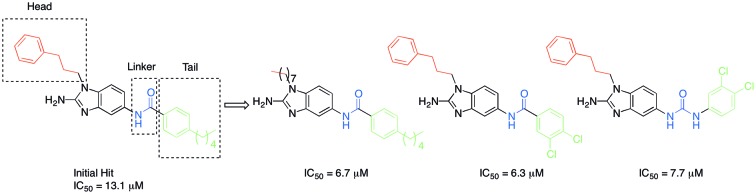

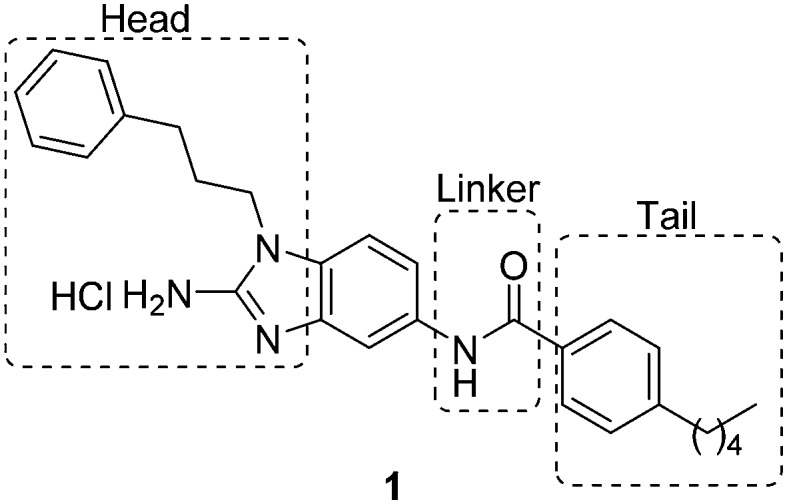

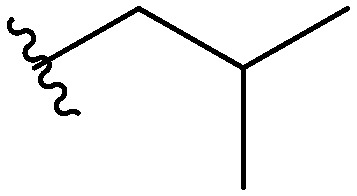

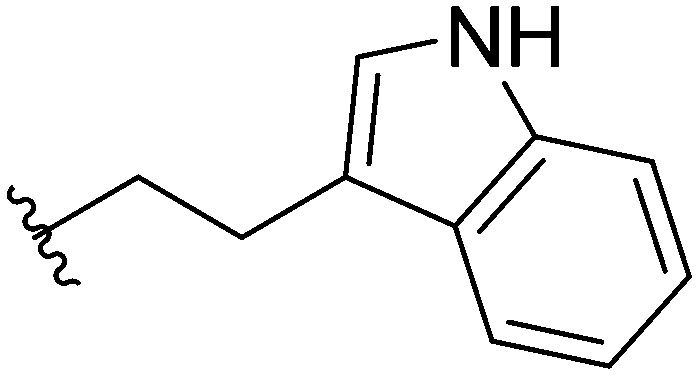

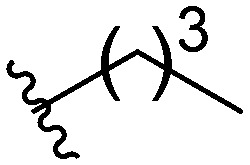

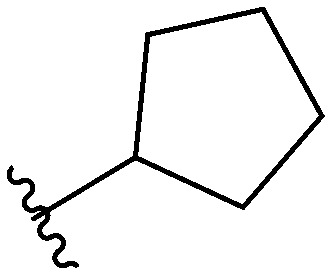

Recently, there have been reports of derivatized 2-aminoimidazoles (2-AIs) that inhibit S. Typhimurium biofilm formation.7–12 As our group has been deeply involved in exploring the antibiofilm potential of 2-AIs, we were curious if there were 2-AI derivatives in our library, or derivatives of other nitrogen-dense heterocycles that we have assembled and assayed for their antibiofilm activities, that possessed activity against S. Typhimurium. As S. Typhi is a human-specific pathogen, reliable murine pathogenic serovars such as S. Typhimurium have been used to model S. Typhi infections, allowing for future in vivo testing.13,14 We performed an initial library screen for inhibitors of S. Typhimurium biofilm formation and identified 2-aminobenzimidazole (2-ABI) compound 1 as one lead compound that returned an IC50 value of 13.1 ± 0.6 μM. Previously, we have shown that 2-ABIs display a wide variety of biological activity including antibiotic activity against MRSA and MDR A. baumannii,15 antibiofilm activity against Gram-positive bacteria,16 and the ability to potentiate β-lactam antibiotic activity against Mycobacterium smegmatis and M. tuberculosis.17 With this compound in hand, we decided to probe the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of the 2-ABIs against S. Typhimurium biofilms. Herein we report the results of this SAR study of the 2-ABI scaffold, focusing on three regions: the head region, the linker and the tail region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Structure of original hit compound 1, regions of modification.

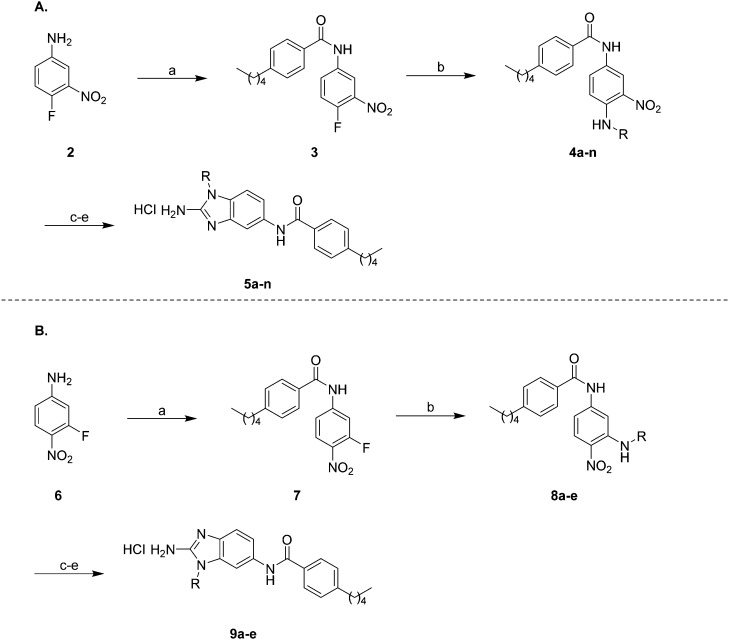

The first region of the molecule we decided to modify was the head region of the 2-ABI using a synthetic scheme previously described by our group (Scheme 1A).18 Briefly, 4-fluoro-3-nitroaniline 2 was acylated with 4-pentylbenzoyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine and 4-dimethylaminopyrimidine (DMAP) in DCM for 16 hours at room temperature to yield compound 3. SNAr substitution of compound 3 with commercially available amines in refluxing ethanol for 16 hours yielded compounds 4a–n. Subsequent reduction of the nitro group with ammonium formate and 10% Pd/C in ethanol at reflux followed by cyclization with cyanogen bromide in DCM at room temperature yielded 2-ABIs 5a–n. The unsubstituted 2-ABI derivative, compound 5o, was prepared using a previously published method.15,19

Scheme 1. (A) Synthetic route to compounds 5a–n and (B) synthetic route to compounds 9a–e: (a) 4-pentylbenzoyl chloride, DMAP, Et3N, DCM, 16 h (b) RNH2, EtOH, reflux, 16 h (c) NH4HCO2, 10% Pd/C, EtOH, reflux, 3 h (d) CNBr, DCM, 16 h (e) HCl, MeOH.

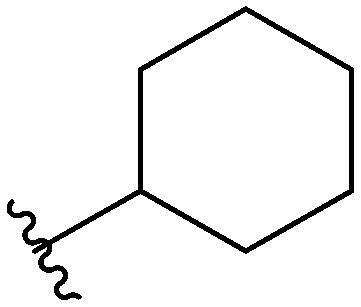

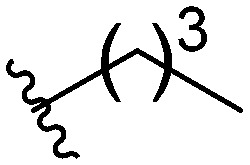

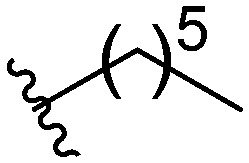

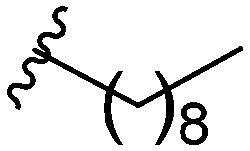

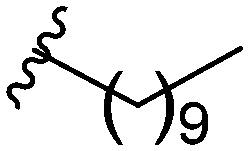

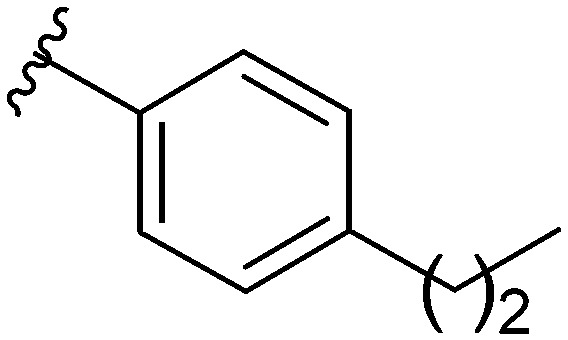

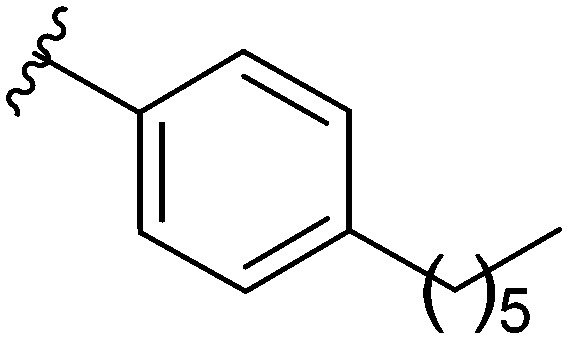

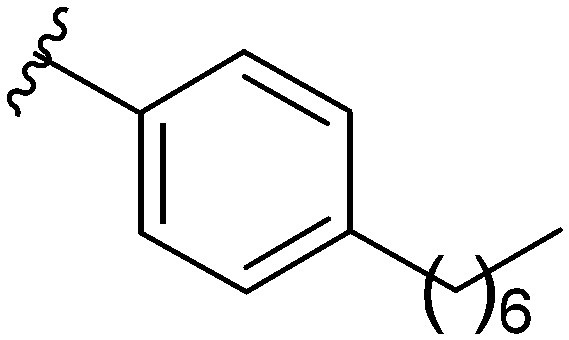

Three head group substitutions, n-octyl (5a), butyl phenyl (5b), and n-hexyl (5c) displayed improved activity (Table 1) over the parent compound. Isobutyl substitution (compound 5d) or substitution with tryptamine (5e) returned an IC50 value between 10–15 μM, similar to that of parent compound 1 (IC50 values were only quantified for compounds that had marked improvement over compound 1). Substitution with cyclopentyl (5g) or cyclohexyl rings (5h) returned slightly higher IC50 values compared to the parent (15–20 μM). Shortening the phenyl chain to two methylenes also reduced activity, with compound 5i returning an IC50 value of 20–40 μM (ESI†). Replacement of the phenyl ring on compound 5i with an imidazole (5j) ring also returned an IC50 value of 20–40 μM. Alkyl chains with less than four carbon atoms (5k, 5l) or longer than eight carbon atoms (5m, 5n) reduced or completely abolished antibiofilm activity. Removal of the head group (compound 5o) from the 2-ABI lowers the IC50 from 13.1 ± 0.6 μM to 20–40 μM, demonstrating the necessity of the head group for biofilm inhibitory activity.

Table 1. IC50 values of para 2-ABI, compounds 5a–h, and meta 2-ABI, compounds 9a–b. Full inhibition data can be found in the ESI.

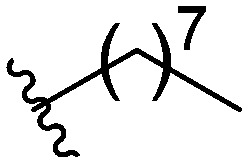

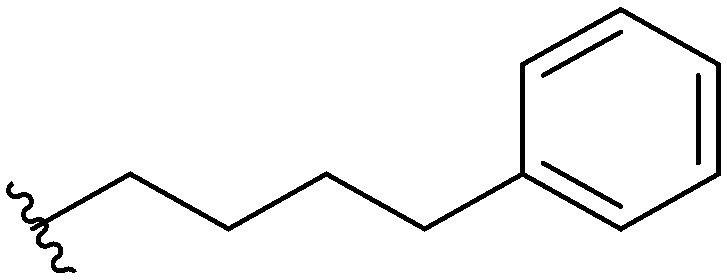

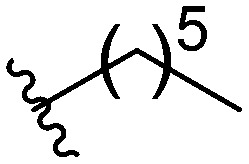

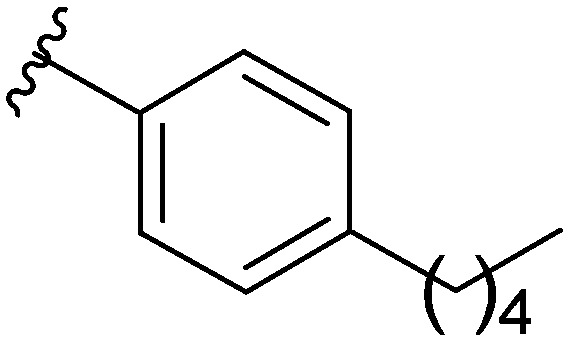

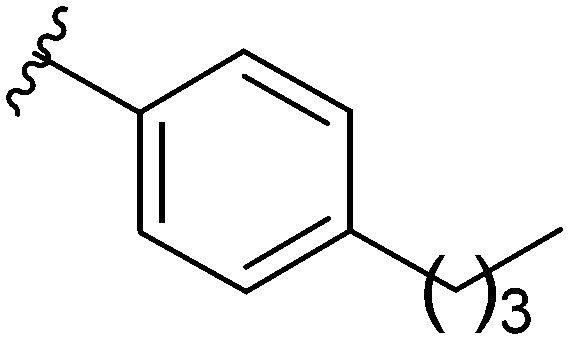

| Compound | R | IC50 (μM) |

| 5a |

|

6.66 ± 0.32 |

| 5b |

|

9.59 ± 0.23 |

| 5c |

|

10.8 ± 0.56 |

| 1 |

|

13.1 ± 0.6 |

| 5d |

|

10–15 |

| 5e |

|

10–15 |

| 5f |

|

15–20 |

| 5g |

|

15–20 |

| 5h |

|

15–20 |

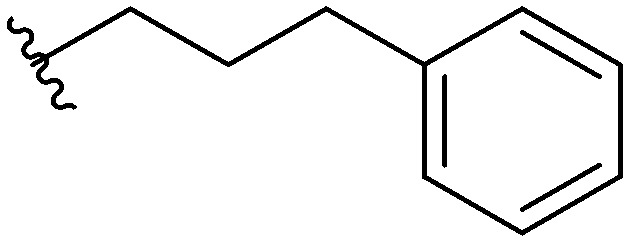

| 9a |

|

10–15 |

| 9b |

|

10–15 |

After investigating different head group substitutions in the para position relative to the amide, analogues with the head group substitution meta to the amide were prepared. The synthetic route to these compounds (Scheme 1B), is identical to that of the para analogues (Scheme 1A) except the starting material is 3-fluoro-4-nitroaniline 6. Compared to their para substituted counterparts, the meta analogues did not display a significant increase in activity (Table 1). Only the butyl analogue 9a (IC50 10–15 μM) displayed increased activity compared to butyl para analogue 5f (IC50 15–20 μM). n-Hexyl analogue 9b displayed almost identical activity to the para n-hexyl analogue 5c, returning an IC50 of 10–15 μM. Methyl (9c), ethyl (9d), and isopropyl (9e) analogues all displayed IC50 values of 20–40 μM (ESI†).

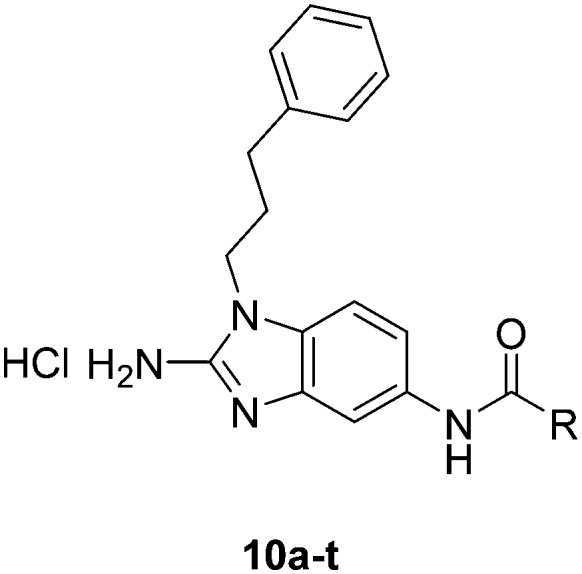

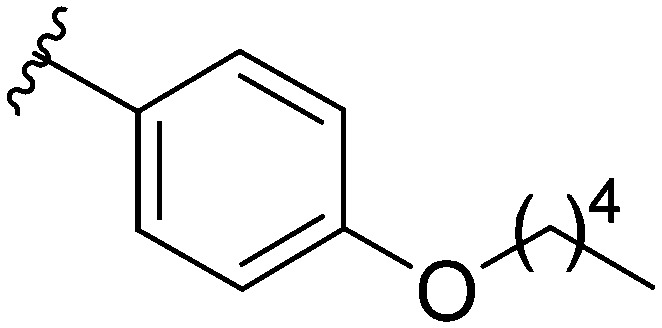

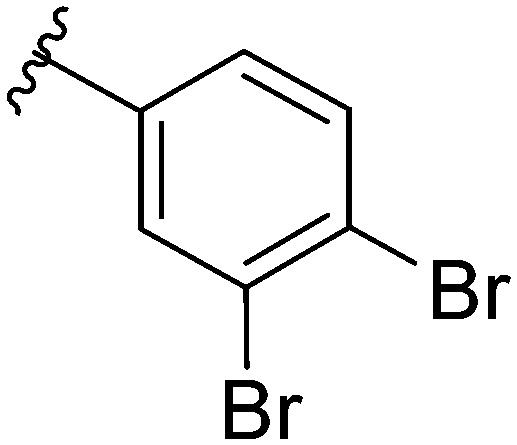

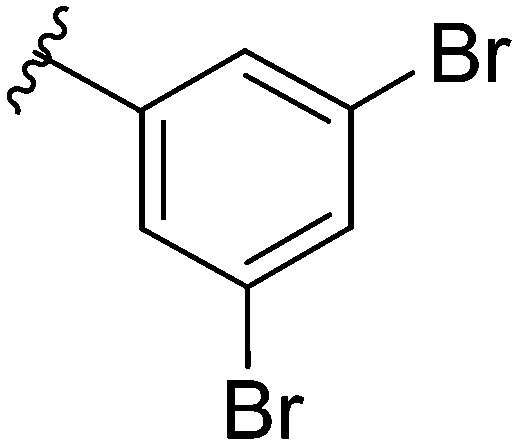

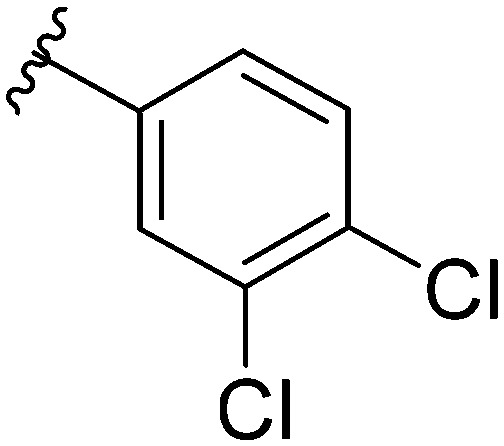

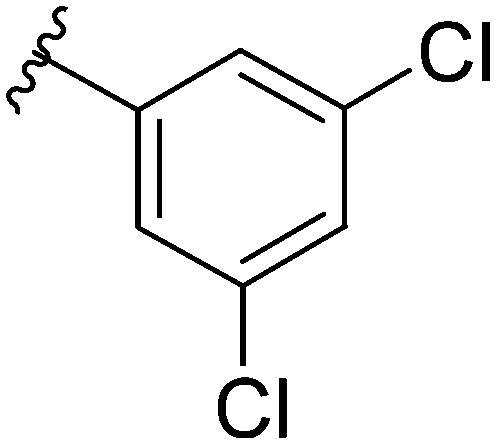

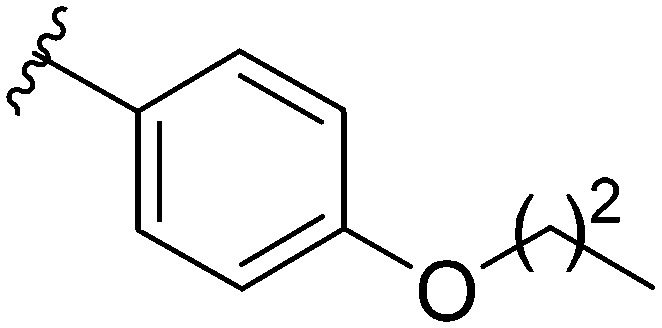

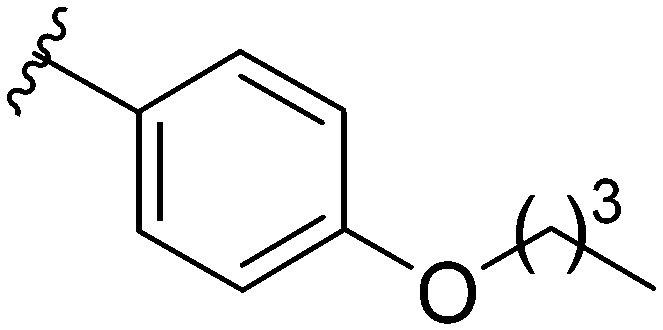

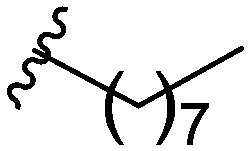

After modifying the head region of the molecule, substitutions to the tail of the molecule were made in an effort to improve the antibiofilm ability of the parent compound. Previously, various 2-ABI derivatives with an identical head group to the parent compound 1 and various tails were prepared (Fig. 2).17 As these compounds were readily available in our laboratory, their anti-Salmonella biofilm activity was investigated. Halogenation (10b, 10c and 10d) of the aromatic ring lowers the IC50 value when compared to a 4-pentylbenzoyl group, all returning IC50 values of less than 7 μM (Table 2). The 3,5-dichloro analogue 10e displays lower activity compared to the other halogenated tails, but displays essentially equivalent activity to the parent compound 1. Addition of a pentoxybenzoyl group (10a) returns the lowest IC50 observed, with an IC50 of 5.22 ± 0.11 μM. Although substituted benzoyl groups are favored in the most active compounds, removal of the aromatic ring in favor of a straight alkyl chain is tolerated as observed with nonanoyl (10h) and decanoyl (10i) tails. 4-Butylbenzoyl (10f), and 4-propoxybenzoyl (10g) tails all returned an IC50 value of 10–15 μM, similar to that of the parent compound (1) and the 3,5-dichlorobenzoyl compound (10e). Additional analogues were investigated, but all displayed lower activity in comparison to the parent compound. 4-Butoxybenzoyl (10j), 4-propylbenzoyl (10k), 4-hexylbenzoyl (10l), 4-heptylbenzoyl (10m), and octanoyl (10n) tails all returned IC50 values of 15–20 μM. 4-Ethylbenzoyl (10o) and hexanoyl (10p) tails returned IC50 values between 20–40 μM (ESI†). Lastly, heptanoyl (10q), 4-octylbenzoyl (10r), undecanoyl (10s), and tridecanoyl (10t) tails returned IC50 values of greater than 40 μM.

Fig. 2. Structure of compounds 10a–t with various tail substitutions.

Table 2. IC50 values of 2-ABIs with different tails, compounds 10a–n. Full inhibition data can be found in the ESI.

| Compound | R | IC50 (μM) |

| 10a |

|

5.22 ± 0.11 |

| 10b |

|

5.38 ± 0.79 |

| 10c |

|

5.58 ± 0.21 |

| 10d |

|

6.30 ± 1.29 |

| 1 |

|

13.1 ± 0.6 |

| 10e |

|

10–15 |

| 10f |

|

10–15 |

| 10g |

|

10–15 |

| 10h |

|

10–15 |

| 10i |

|

10–15 |

| 10j |

|

15–20 |

| 10k |

|

15–20 |

| 10l |

|

15–20 |

| 10m |

|

15–20 |

| 10n |

|

15–20 |

The last region of the 2-ABIs that we were interested in modifying was the linker region. The 2-ABIs previously synthesized in our laboratory15–18 that served as the basis for the 2-ABIs used in this study have featured an amide linkage, with the nitrogen in the amide connected to the 2-ABI head of the molecule. Previous studies on other 2-AI natural products have demonstrated the effect that modification of the amide moiety can have on a compound's ability to control bacterial behavior as well as its toxicity in C. elegans.20 With this in mind, we aimed to synthesize 2-ABI derivatives with a reverse amide moiety as well as a urea moiety replacing the amide. Compound 10d was chosen as the compound for further analog development due to its predicted reduced metabolic liabilities.

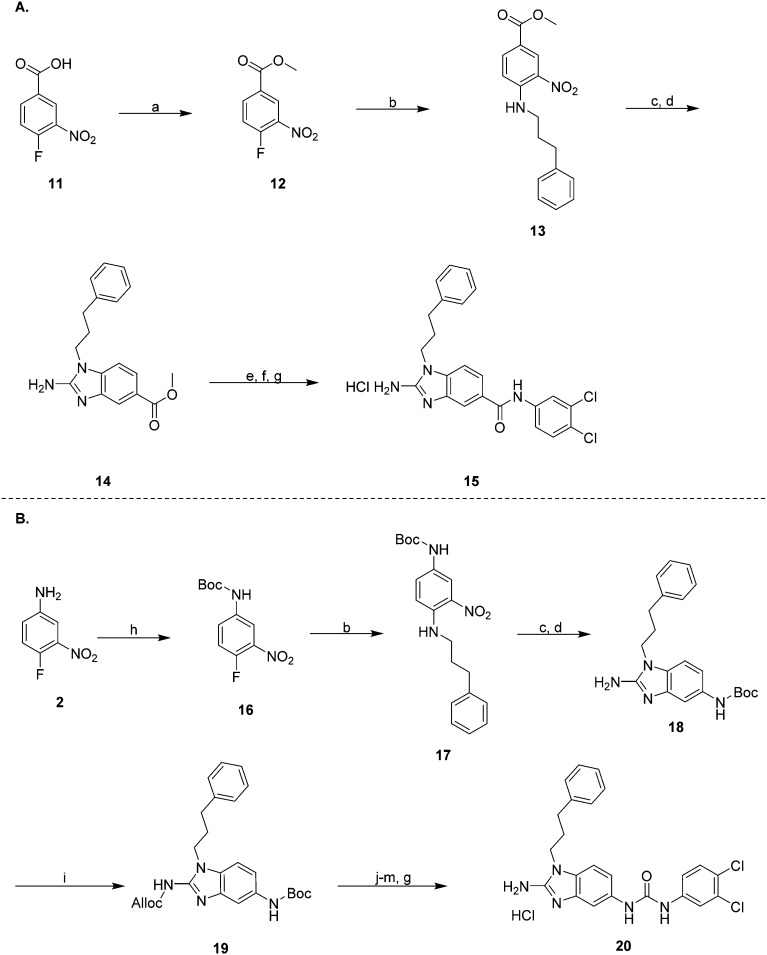

The synthesis of the reverse amide analogue (Scheme 2A) began by reacting 4-fluoro-3-nitrobenzoic acid with thionyl chloride in methanol at 0 °C, warming to room temperature overnight to yield the methyl ester 12. Compound 12 was then reacted with 3-phenyl-1-propylamine in ethanol at reflux to yield 13. Reduction of the nitro group followed by cyclization with cyanogen bromide in DCM at room temperature yielded the 2-ABI 14. Lastly, saponification of the methyl ester with sodium hydroxide in 1 : 1 MeOH/H2O followed by EDC coupling of the carboxylic acid with 3,4-dichloroaniline delivered the reverse amide 2-ABI 15.

Scheme 2. (A) Synthetic route to compound 15 and (B) synthetic route to compound 20: reagents and conditions (a) SOCl2, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 16 h (b) 3-phenyl-1-propylamine, EtOH, reflux, 16 h (c) NH4HCO2, 10% Pd/C, EtOH, reflux, 3 h (d) CNBr, DCM, 16 h (e) NaOH, 1 : 1 MeOH : H2O, reflux, 2 h (f) EDC, 3,4-dichloroaniline, Et3N, DMAP, 2 : 1 DCM : DMF, rt, 16 h (g) HCl, MeOH (h) Boc2O, DMAP, Et3N, DCM, rt, 16 h (i) Alloc-Cl, Et3N, Sc(OTf)3, DCM, rt, 16 h (j) 30% TFA : DCM, rt, 4 h (k) 3,4-dichloroaniline, triphosgene, Na2CO3, DCM-H2O, rt, 16 h (l) Pd(PPh3)4, NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C to rt, 1 h (m) 12N HCl, pH 1, rt, 2 h.

Synthesis of the urea analogue (Scheme 2B) began with the Boc protection of 4-fluoro-3-nitroaniline, yielding 16. Compound 16 was then reacted with 3-phenyl-1-propylamine to yield the diaminobenzene 17. Reduction of the nitro group using ammonium formate and 10% Pd/C in ethanol at reflux followed by cyclization with cyanogen bromide in DCM at room temperature yielded Boc-protected 2-ABI 18. Alloc protection of the 2-ABI head proceeded smoothly utilizing scandium(iii) triflate as a Lewis-acid catalyst in DCM overnight at room temperature, yielding alloc protected 2-ABI 19. Boc deprotection of compound 20 followed by coupling with 3,4-dichloroaniline using triphosgene yielded the Alloc protected 2-ABI urea. Finally, Alloc deprotection with Pd(PPh3)4 and NaBH4 yielded the target 2-ABI urea 20.

While the reverse amide analogue 15 displayed a two-fold greater IC50 (12.6 ± 1.8 μM) than that of the parent compound 10d, the urea analogue 20 displayed only a slight reduction in IC50 value from 6.30 ± 1.29 to 7.69 ± 0.25 μM, demonstrating that the linker group of the 2-ABIs can be modified while retaining biofilm inhibitory activity against S. Typhimurium. Additionally, compounds 10a and 20 showed no toxicity to planktonic bacterial growth at their IC50 values, indicating that they are non-toxic biofilm inhibitors (ESI†).

Conclusions

After the identification of 2-ABI compound 1 as a S. Typhimurium biofilm inhibitor, probing of the SAR of the 2-ABIs elucidated six new analogues with IC50 values of less than 10 μM. Utilizing the same para-pentyl benzoyl tail as the parent compound 1, structural modifications to the head of the 2-ABIs in the para position to the amide yielded compounds 5a and 5b with IC50 values of 6.66 ± 0.32 and 9.59 ± 0.23 μM respectively. Modification of the tail region yielded compounds 15a (5.22 ± 0.11 μM), 15b (5.38 ± 0.79 μM), 15c (5.58 ± 0.21 μM), and 15d (6.3 ± 1.29 μM) that displayed improved activity. Modification of the linker between the head and the tail yielded the urea compound 20 with a comparable IC50 (7.69 ± 0.25 μM) to that of the amide parent compound, 10d (6.30 ± 1.29 μM). Substitution the 2-ABI head at the meta position to the amide (9a–e) and reversal of the amide moiety (15) did not produce an increase in activity. Compounds 10a and 20 were then shown to be non-toxic to planktonic bacterial growth at their IC50 values, demonstrating that they show specific anti-S. Typhimurium biofilm inhibitory activity. Additionally, compounds 10d and 10e and other related 2-ABIs17 displayed no toxicity to G. mellonella at 400 mg kg–1 (ESI†), thus making them potential candidates for future in vivo studies.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to C. M. (GM05579) and (J. S. G. AI 116917) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c8md00298c

References

- Truusalu K., Naaber P., Kullisaar T., Tamm H., Mikelsaar R.-h., Zilmer K., Rehema A., Zilmer M., Mikelsaar M. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2009;16:180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford R. W., Rosales-Reyes R., Ramirez-Aguilar Mde L., Chapa-Azuela O., Alpuche-Aranda C., Gunn J. S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:4353–4358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000862107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P. S., Consterton J. W. Lancet. 2001;358:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan R. M., Costerton J. W. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J. F., Alberts H., Lee J., Doolittle L., Gunn J. S. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:222. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn J. S., Marshall J. M., Baker S., Dongol S., Charles R. C., Ryan E. T. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolat'ev D. S., Bariwal J. B., Steenackers H. P., De Keersmaecker S. C., Van der Eycken E. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:9465–9468. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenackers H. P., Ermolat'ev D. S., Savaliya B., De Weerdt A., De Coster D., Shah A., Van der Eycken E. V., De Vos D. E., Vanderleyden J., De Keersmaecker S. C. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:472–484. doi: 10.1021/jm1011148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenackers H. P., Ermolat'ev D. S., Savaliya B., Weerdt A. D., Coster D. D., Shah A., Van der Eycken E. V., De Vos D. E., Vanderleyden J., De Keersmaecker S. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:3462–3473. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robijns S. C., De Pauw B., Loosen B., Marchand A., Chaltin P., De Keersmaecker S. C., Vanderleyden J., Steenackers H. P. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012;65:390–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenackers H., Ermolat'ev D., Trang T. T., Savalia B., Sharma U. K., De Weerdt A., Shah A., Vanderleyden J., Van der Eycken E. V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:3671–3678. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42282h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trang T. T. T., Dieltjens L., Hooyberghs G., Waldrant K., Ermolat'ev D. S., Van der Eycken E. V., Steenackers H. P. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:1470–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Lu R., Zhang Y. G., Sun J. J. Visualized Exp. 2010;(39):1947. doi: 10.3791/1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truusalu K., Mikelsaar R. H., Naaber P., Karki T., Kullisaar T., Zilmer M., Mikelsaar M. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huigens, 3rd R. W., Reyes S., Reed C. S., Bunders C., Rogers S. A., Steinhauer A. T., Melander C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S. A., Huigens, 3rd R. W., Melander C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9868–9869. doi: 10.1021/ja9024676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. V., Blackledge M. S., Lindsey E. A., Ackart D. F., Jeon A. B., Obregon-Henao A., Melander R. J., Basaraba R. J., Melander C. Angew.Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:3940–3944. doi: 10.1002/anie.201612006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey E. A., Brackett C. M., Mullikin T., Alcaraz C., Melander C. MedChemComm. 2012;3:1462–1465. doi: 10.1039/C2MD20244A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K., Hannak R. B., Guo M. J., Kirby A. J., Hilvert D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:6189–6196. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. J., Reyes S., Stowe S. D., Tucker A. T., Ballard T. E., Mathies L. D., Cavanagh J., Melander C. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4582–4585. doi: 10.1021/jm900378s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.