Abstract

Three new grayanane diterpenoids, pierisoids C‒E (1–3), as well as 10 known ones (4–13), were evaluated from the flowers of Pieris formosa, which is used as an insecticide in rural areas of China. Their structures were elucidated on the basis of extensive 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data analyses. Significant antifeedant activity of 1, 3 and 10 against the beet armyworm (Spodoptera exigua) was found, indicating that these diterpenoids might also be involved in the plant defense against insect herbivores.

Keywords: Pierisformosa, Ericaceae, grayanane diterpenoids, antifeedant activity

1. Introduction

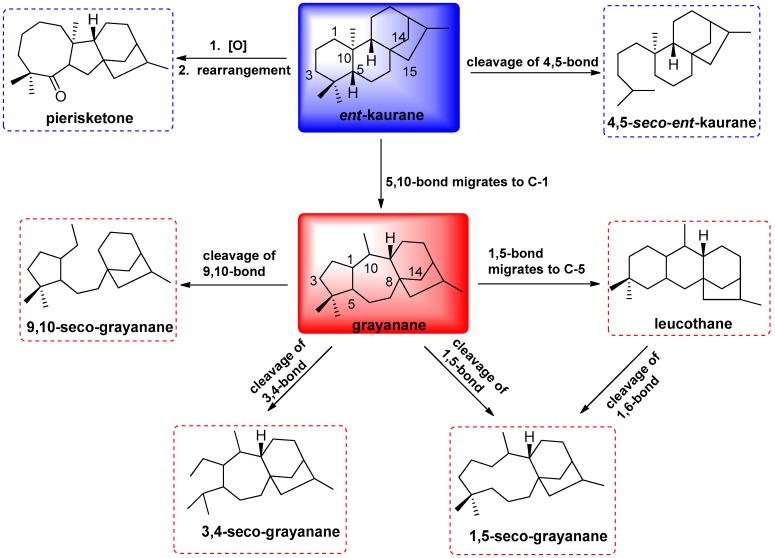

Grayanoids represent a special type of diterpenoids, which have been limited to the plants of Ericaceae, such as the genera Pieris, Rhododendron, Kalmia, Craibiodendron and Leucothoe [1,2]. The grayanoid diterpenoids, as the characteristic secondary metabolites of the plants of Ericaceae, have attracted much attention from chemists and biologists not only for their intriguing structure but also for their diverse bioactivity, especially for their toxicity, as well as their analgesic, significant antifeedant, and insecticidal activity [3,4,5]. To date, 15 types of diterpenoid skeleton have been reported, including grayanane (A-nor-B-homo ent-kaurane) [5], 1,5-secograyanane [6], 3,4-secograyanane [7], 9,10-secograyanane [8], 1,10:2,3-disecograyanane [9], leucothane (A-homo-B-nor grayanane) [10], kalmane (B-homo-C-nor grayanane) [11], 1,5-secokalmane [12], micranthane (C-homo grayanane) [13], mollane (C-nor-D-homo grayanane) [14], rhodomollane (D-homo grayanane) [15], ent-kaurane, 4,5-seco-ent-kauran [16], pierisketane (A-homo-B-nor-ent-kaurane) [17], and rhodomollane [18]. All of these diterpenoid types are assumed to be derived biogenetically from the ent-kanrane skeleton. Notably, eight types of skeletons have been produced by the narrow genus Pieris, whose representative plant is Pieris formosa D. Don. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biogenetic relationships of grayanane carbon skeletons from the genus Pieris.

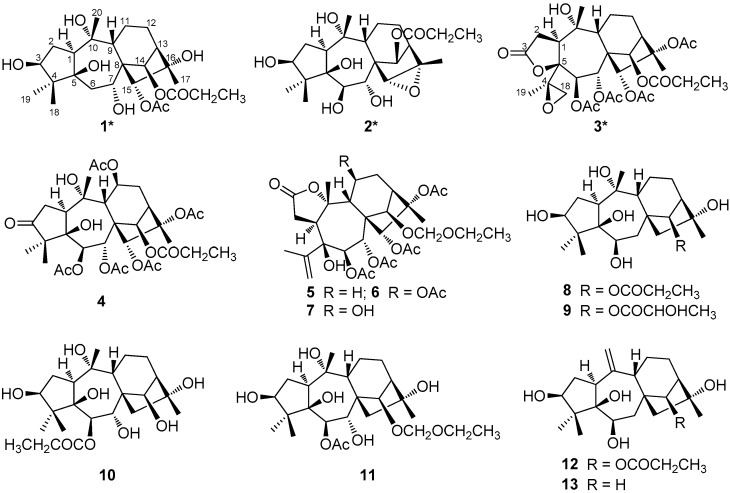

P. formosa, an evergreen shrub, is distributed mainly in the hilly regions and valleys of southern and southwestern China. The juice of both its fresh leaves and flowers are used as an insecticide and lotion for the treatment of ring worm and scabies, in folk medicine [19,20,21]. More than 60 grayanane diterpenoids with grayanane, 1,5-secograyanane, 3,4-seco-grayanane, 9,10-seco-grayanane, leucothane, 4,5-seco-ent-kauran, and pierisketane carbon skeletons have been isolated from the leaves, flowers, fruits, stems and roots of P. formosa [3,17,22,23,24,25]. In our previous work, two new highly esterified 3,4-seco-grayanane diterpenoids, pierisoids A and B, were reported from the flowers of P. formosa [20]. In our continuing endeavor to identify structurally unique and biologically diverse grayanoids from famous poisonous plants, three additional new grayanoids, pierisoids C‒E (1‒3) (Figure 2), together with ten known ones (4‒13) (Figure 2) were isolated from the flowers of P. formosa. Herein, the isolation and structural elucidation of 1‒3 and their antifeedant activity against the generalist plant-feeding cotton bollworm are described.

Figure 2.

Structures of grayanane diterpenoids 1–13 isolated from P. formosa.

2. Results

2.1. Structural Elucidation of Compounds 1–3

Compound 1, = +14.3 (c = 0.2, MeOH), was isolated as colorless crystals. Its molecular formula was determined to be C25H40O9 according to its high-resolution (HR) ESI-MS (found: m/z 507.2567 [M + Na]+, calcd.: 507.2570) and 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra. IR absorptions at 3550, 3484, 1752 and 1729 cm−1 were indicative of hydroxyl and ester carbonyl functional groups. In the 1H-NMR spectrum (Table 1), four tertiary methyls at δH 0.91, 1.11, 1.27 and 1.41 (each 3H of singlet), one acetyl methyl at δH 2.10 (s, 3H), and one primary methyl at δH 1.11 (3H, t, J = 7.6 Hz) were clearly observed. Additionally, four singlets (δH 3.06, 3.39, 4.93 and 5.59), two triplets (δH 3.60 and 3.62, J = 5.0 Hz), and one doublet (δH 4.20, d, J = 5.4 Hz) were ascribable to either oxygenated methine or free hydroxyl groups. Other signals which were mostly overlapped centered between 1.58 and 2.85 ppm, resonating from either methine or methylene signals. The 13C-NMR spectrum revealed 25 carbon resonances, which were further classified by DEPT-90 and DEPT-135 spectra as six methyls, five methylenes, seven methines including four oxygenated ones (δC 72.4, 82.1, 82.5, and 85.0), seven quaternary carbons including three oxygenated ones (δC 78.4, 79.6, and 84.1), and two carbonyl carbons (δC 170.3 and 173.4). By analysis of the HSQC spectral data, all proton signals, except for the two singlets at δH 3.06 and 3.39 and the doublet at δH 4.20, could be assigned unambiguously to their respective carbons, suggesting that the signals at δH 3.06, 3.39 and 4.20 were assignable to free hydroxyl groups. Moreover, the existence of a propionyloxy-group was determined from analysis of the 1H-1H COSY and HMBC spectra. The above spectroscopic evidence suggested a highly oxygenated grayanane diterpenoid for 1.

Table 1.

1H- (400 MHz) and 13C- (100 MHz) NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 1–3 in acetone-d6 (δ (ppm), J (Hz)).

| No. | 1 a | 2 b | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | |

| 1 | 2.74 dd (11.6, 5.2) | 50.9 d | 2.77 m | 50.9 d | 3.08 m | 52.6 d |

| 2a 2b |

2.06 m 2.27 m |

35.4 t | 2.05 m 2.22 m |

35.9 t | 2.47 m 2.73 dd (18.9, 11.8) |

32.8 t |

| 3 | 3.60 t (5.0) | 82.5 d | 3.53 dd (1.5, 5.1) | 83.0 d | 174.0 s | |

| 4 | 51.4 s | 52.3 s | 62.5 s | |||

| 5 | 84.1 s | 83.1 s | 87.5 s | |||

| 6 | 2.05 m (2H) | 34.0 t | 3.91 overlap | 78.2 d | 6.04 d (9.6) | 69.8 d |

| 7 | 3.62 t (5.0) | 72.4 d | 3.41 overlap | 78.3 d | 5.23 d (9.7) | 68.7 d |

| 8 | 54.5 s | 53.8 s | 56.1 s | |||

| 9 | 2.08 m | 54.6 d | 2.08 m | 49.9 d | 2.32 m | 47.0 d |

| 10 | 78.4 s | 77.7 s | 77.4 s | |||

| 11a 11b |

1.58 m 1.90 m |

21.8 t | 1.71 m 1.81 m |

21.6 t | 1.98 m 2.03 m |

21.1 t |

| 12a 12b |

1.58 m 2.23 m |

27.0 t | 1.68 m 2.35 m |

28.1 t | 1.74 m 2.08 m |

25.8 t |

| 13 | 2.05 overlap | 52.9 d | 2.24 m | 47.6 d | 3.10 overlap | 46.4 d |

| 14 | 5.59 s | 82.1 d | 5.52 s | 76.4 d | 6.43 s | 79.3 d |

| 15 | 4.93 s | 85.0 d | 3.26 s | 68.6 d | 5.27 s | 86.2 d |

| 16 | 79.6 s | 61.3 s | 88.4 s | |||

| 17 | 1.27 s (3H) | 22.8 q | 1.45 s (3H) | 14.6 q | 1.55 s (3H) | 19.4 q |

| 18 | 1.11 s (3H) | 18.5 q | 1.23 s (3H) | 19.3 q | 2.49 d (5.0) 2.98 d (4.9) |

52.8 t |

| 19 | 0.91 s (3H) | 23.0 q | 0.97 s (3H) | 23.2 q | 1.34 s (3H) | 17.4 q |

| 20 | 1.41 s (3H) | 27.8 q | 1.41 s (3H) | 28.2 q | 1.51 s (3H) | 33.6 q |

| 6-OAc | 2.02 s (3H) | 20.6 q | ||||

| 169.4 s | ||||||

| 7-OAc | 2.10 s (3H) | 21.6 q | ||||

| 169.8 s | ||||||

| 14-OPr | 1.11 t (3H, 7.6) 2.85 m (2H) |

9.6 q | 1.08 t (3H, 7.6) 2.27 m (2H) |

9.5 q | 1.08 t (3H, 7.5) 2.36 m (2H) |

9.1 q |

| 28.4 t | 28.5 t | 28.2 t | ||||

| 173.4 s | 173.8 s | 174.0 s | ||||

| 15-OAc | 2.10 s (3H) | 21.0 q | 1.98 s (3H) | 20.8 q | ||

| 170.3 s | 171.6 s | |||||

| 16-OAc | 1.98 s (3H) | 22.7 q | ||||

| 169.8 s | ||||||

a Hydroxyl groups of 1: δH 4.20 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 3-OH), 3.39 (s, 10-OH), 3.06 (s, 16-OH); b Hydroxyl groups of 2: δH 3.91 (overlap, 3-OH), 3.64 (s, 5-OH), 3.51 (s, 10-OH), 3.41 (overlap, 6-OH), 3.34 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 7-OH).

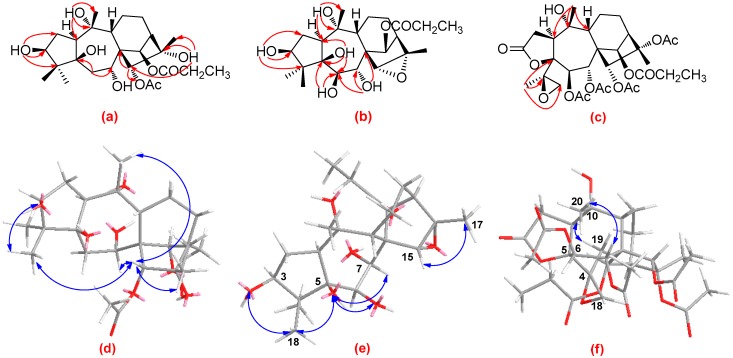

Detailed analysis of the 1D (1H and 13C) and 2D (1H-1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC) NMR spectra (Figures S1–S6 in supplementary data) of 1 revealed that its structure closely resembled that of asebotoxin VIII [19,26], a known grayanane diterpenoid previously isolated from both P. japonica and P. formosa. The obvious difference between the two compounds was that the acetoxy group located at C-6 in asebotoxin VIII migrated to C-15 in 1, as indicated by the HMBC correlations from H-15 (δH 4.93, s) to the acetoxy carbonyl group at δC 170.3 and from H2-6 (δH 2.05, m) to C-5 (δC 84.1) and C-7 (δC 72.4) (Figure 3a). In the ROESY spectrum, the correlations of H-15 with Me-18 as well as Me-20 suggested that H-15, Me-18, and Me-20 were all in the same β-orientation (Figure 3d). In addition, the correlations of 3-OH with Me-18, and of 15-H with 7-H and Me-17 suggested that 3-OH, H-7 and Me-17 were also in β-orientation (Figure 3d). Further analysis of the ROESY spectrum indicated the configurations of the remaining functional groups in 1 were the same as those in asebotoxin VIII, namely 3β, 5β, 7α, 10α, 16α-pentahydroxy, and 14β-propionyloxy. Accordingly, the structure of 1 was deduced as shown in Figure 2, and was named pierisoid C.

Figure 3.

(a)–(c) are key HMBC correlations of pierisoids C–E, respectively; (d)–(f) are selected ROESY correlations of pierisoids C–E, respectively.

Compound 2 was obtained as colorless oil with a molecular formula of C23H36O8, as determined by a combination of HR-EI-MS and NMR spectra (including 1H, 13C, and DEPT) (Figures S7–S2 in supporting information). The resemblance of the NMR spectra of 2 (Table 1) with those of 1 disclosed that 2 was another grayanane diterpenoid structurally similar to 1. The major difference was the replacement of a methylene carbon in 1 by an oxygen-occurring methine in 2 (δC 78.2), suggesting that either C-6, or C-11, or C-12 of 2 was oxygenated. In the HMBC spectrum of 2, the HMBC correlations from 5-OH to the methine carbon at δC 78.2 indicated that this methine was ascribable to C-6 (Figure 3b). Carefully comparison of 13C-NMR spectral data of 2 with those of 1 (Table 1) obviously found that the upfield-shift of C-15 (δC 68.6) and C-16 (δC 61.3) in 2, indicated an oxygen bridge, was formed between C-15 and C-16; this was supported by the HR-EI-MS spectrum. In the ROESY spectrum of 2, the correlations of Me-17 with H-15; of 3-OH and 5-OH with Me-18; and of 5-OH with 6-OH and H-7 indicated that 3-OH, 5-OH, 6-OH, H-7, H-15, and Me-17 were in the same β-orientation (Figure 3e). Consequently, the structure of 2 was determined as shown in Figure 2 and was named pierisoid D.

Compound 3, colorless crystals, has a molecular formula of C31H42O14, as determined by a combination of HR-EI-MS and NMR spectra (including 1H-, 13C-, and DEPT) (Figures S13–S18 in supplementary data). Its spectroscopic data were very similar to those of secorhodomollolide B, a 3,4-secograyanane diterpenoid also isolated from P. formosa [27]. The only difference between them was that the terminal double bond between C-4 (δC 146.0) and C-18 (δC 116.7) in secorhodomollolide B was replaced by a 4,18-oxirane group (δC 62.5 and 52.8) in 3, which was confirmed by the HMBC correlations from Me-19 (δH 1.34, s) to C-4, C-5 (δC 87.5) and C-18 (Figure 3c). Such an oxirane moiety has also been found in pierisoid A, another 3,4-secograyanane diterpenoid we reported from the flowers of P. formosa [20]. In the ROESY spectrum of 3, the correlations of Me-19 with H-1, and of Me-20 with H-7 indicated that Me-19 and H-1 were in α-orientation and Me-20 coupled with H-7 were in β-orientation (Figure 3f). Therefore, compound 3 was identified as shown in Figure 2 and was named pierisoid E.

Ten known diterpenoids (Figure 2), namely, pierisformotoxin C (4) [24], secorhodomollolides C (5), D (6), and F (7) [28], asebotoxins I (8), II (12), IV (10), and VIII (11) [26,29], pieristoxin I (9) [29], and pierisformosin (13) [30] were also isolated from P. formosa and were identified by comparison of their spectroscopic data with those reported in the literature.

2.2. Antifeedant Activity of Compounds 1, 3, 4, and 10

The antifeedant activity of 1, 3, 4 and 10 against the generalist insect herbivore, beet armyworm (Spodoptera exigua), was assayed as previously described [31,32,33]. Compounds 1, 3 and 10 were found to be potential deterrents of the beet armyworm, with EC50 values of 10.91, 33.89 and 6.58 μg/cm2, respectively. It seems that the antifeedant activity of grayanane diterpenoids may be reduced with the increase of degree of esterification. Although less active than the commercial neem oil containing 1% azadirachtin (EC50 = 3.71 μg/cm2) (Table 2), the significant antifeedant activity of these individual compounds and the overall effect they might have suggest a defensive role of grayanane diterpenoids for P. formosa against insect herbivores.

Table 2.

Antifeedant activity of compounds 1, 3, 4, and 10 against Spodoptera exigua.

| Compound | Molecular Formula | m/z | EC50 (µg/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C25H40O9 | 484 | 10.91 |

| 3 | C31H42O14 | 638 | 33.89 |

| 4 | C33H46O15 | 682 | NA |

| 10 | C23H38O8 | 442 | 6.58 |

| Neem oil | - | - | 3.71 |

NA = Not active; “-” = No (Because neem oil is a mixture).

3. Discussion

Compounds 1–3 are highly oxygenated grayanane diterpenoids, which occur extensively in the plants of Ericaceae and exhibit remarkable biological activities, such as antifeedant and insecticidal activities. Compound 2 is a grayanane-type diterpenoid with an unprecedented 15,16-epoxy group in the grayanoids family. Compound 3, a 3,4-seco-grayanane diterpenoid, possesses a 4,18-epoxy substituent, which is also unusual in nature. Compared to compounds 1 and 3, 10 displayed more significant antifeedant activity against S. exigua, which was possibly attributed to the integrity of the A ring.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

Melting points were recorded on an Aisey YLD-6000 instrument and are uncorrected. Column chromatography was performed on 200–300 mesh silica gel (Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory, Qingdao, China). Optical rotations were measured on a Horiba-SEAP-300 spectropolarimeter (Horiba, Tokyo, Japan). UV spectral data were obtained on a Shimadzu-210A double-beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker-Tensor-27 spectrometer with KBr pellets (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, Germany). NMR experiments were carried out on either a Bruker AV-400 or a DRX-500 spectrometer with tetramethyl silane (TMS) as an internal standard (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). MS were recorded on a VG-Auto-Spec-3000 spectrometer (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). TLC (Thin Layer Chromatography) spots were visualized under UV light, by dipping into 10% H2SO4 in EtOH followed by heating. All solvents including petroleum ether (60−90 °C) were distilled before use.

4.2. Plant Materials

The flowers of P. formosa were collected at Qu Jing, Yunnan province, China, in March 2008. The plant material was identified by Dr. Sheng-Hong Li.

4.3. Extraction and Isolation

Air-dried P. formosa flowers (3.5 kg) were powdered and extracted with MeOH (3 × 5 L) at room temperature. The extract was concentrated under reduced pressure and then partitioned between H2O and EtOAc (1:1). The organic layer (EtOAc part) was concentrated and the residue (594 g) was purified by silica gel column chromatography with solvent mixtures of CHCl3−Me2CO (1:0, 9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 1:1 and 0:1) to afford six fractions. Fraction 2 (45.0 g, CHCl3−Me2CO, 9:1) was repeatedly chromatographed on silica gel (CHCl3−Me2CO, 10:1; petroleum ether−Me2CO, 4:1), yielding subfractions A1−A3. Subfraction A1 (7.9 g) was further purified by silica gel column chromatography using petroleum ether-isopropanol (20:1), followed by purification on Sephadex LH-20 columns (CHCl3−MeOH, 1:1) to obtain compounds 4 (6 mg), 5 (5 mg), and 7 (81 mg). Subfraction A2 (6.65 g) was repeatedly separated by silica gel column chromatography eluting with petroleum ether-acetone (6:1) and finally was purified by Sephadex LH-20 columns (CHCl3−MeOH, 1:1; Me2CO) to afford compounds 1 (27 mg), 3 (3 mg), and 6 (6 mg). Subfraction A3 (10.2 g) was separated by silica gel column chromatography eluting with petroleum ether−ethyl acetate (5:1) and petroleum ether−isopropanol (12:1), respectively, and then similarly purified by Sephadex LH-20 columns (CHCl3−MeOH, 1:1; Me2CO) to give 8 (78 mg) and 9 (7 mg). Fraction 3 (4.2 g, CHCl3−Me2CO, 8:2) was separated on a MCI (Middle Chromatogram Isolated) gel column employing solvent mixtures of MeOH−water (6:4, 7:3, 8:2, 9:1, and 1:0), and the resulting subfractions 2 and 3 (7:3 and 8:2 MeOH−water, respectively) were repeatedly chromatographed on silica gel (CHCl3-EtOAc, 4:1; petroleum ether−isopropanol, 10:1) and Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH; Me2CO) columns to yield compounds 2 (18 mg), 10 (45 mg), 11 (8 mg), 12 (9 mg) and 13 (6 mg).

Pierisoid C (1): Colorless crystals; mp 220–222 °C; = +14.3 (c = 0.2, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 209 (1.98), 193 (1.60) nm; IR (KBr) νmax: 3550, 3484, 2976, 2942, 1752, 1729, 1408, 1373, 1261, 1153, 1047 cm−1; ESI-MS: m/z 507 (50) [M + Na]+; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 507.2567 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C25H40O9Na, 507.2570); 1H- and 13C-NMR data: see Table 1.

Pierisoid D (2): Colorless oils; = +16.7 (c = 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 202 (2.48) nm; IR (KBr) νmax: 3441, 3432, 2971, 2939, 1735, 1730, 1630, 1382, 1179, 1049, 1025 cm−1; ESI-MS: m/z 463 (88) [M + Na]+; HR-EI-MS: m/z 440.2420 (calcd. for C23H36O8, 430.2410); 1H- and 13C-NMR data: see Table 1.

Pierisoid E (3): Colorless crystals; mp 271–272 °C; = +12.6 (c = 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 202 (2.29) nm; IR (KBr) νmax: 3441, 2942, 1787, 1734, 1631, 1372, 1264, 1237, 1053 cm-1; ESI-MS: m/z 661 (68) [M + Na]+; HR-EI-MS: m/z 638.2560 (calcd. for C31H42O14, 638.2575); 1H- and 13C-NMR data: see Table 1.

4.4. Antifeedant Activity

Beet armyworms (Spodoptera exigua) were purchased from the Pilot-Scale Base of Bio-Pesticides, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. A modified dual-choice bioassay was performed for an antifeedant test as previously described [20,31,32,33]. The larvae were reared on an artificial diet under a controlled photoperiod (light:dark, 12:8 h) and temperature (25 ± 2 °C). The larvae were starved for 3−4 h before each bioassay. Fresh leaf disks were cut from Brassica chinensis, using a cork borer (1.1 cm in diameter). The treated leaf disks were painted with 10 μL of the test compound in acetone, and control leaf disks were treated with the same amount of acetone. After air drying, the tested and control leaf disks were set in alternating position in the same Petri dish (90 mm in diameter), with moistened filter paper at the bottom. Two-thirds of the instars were placed at the center of the Petri dish. Five replicates were run for each treatment. After feeding for 24 h, the areas of leaf disks consumed were measured. The antifeedant index (AFI) was calculated according to the following formula: AFI = [(C − T)/(C + T)] × 100, where C and T represent the control and treated leaf areas consumed by the insect. The insect antifeedant potency of the test compound was evaluated in terms of the EC50 value, which was determined by probit analysis for each insect species.

5. Conclusions

Terpenoids play an important role in natural product chemistry and biology, such as antifungal and insecticidal activities [34]. Secondary metabolites, such as the grayanane diterpenoids that occur extensively in the plants of Ericaceae, are fascinating for their remarkable toxicity, as well as their significant antifeedant and insecticidal activity. In the current study, three new grayanane diterpenoids, pierisoids C–E (1‒3), as well as 10 known ones (4‒13), were identified from the flowers of P. formosa via their extensive 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data analyses. Notably, compounds 1, 3 and 10, especially 10, exhibited obvious antifeedant activity against the beet armyworm (S. exigua), suggesting that these diterpenoids were important defensive substances in P. formosa against natural enemies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31500275) and the Scientific Research Foundation of Northwest A & F Foundation (2452017175).

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials are available online. 1D (1H- and 13C-) and 2D NMR spectra of compounds 1–3 are available online.

Author Contributions

Designed the research: Sheng-Hong Li. Performed the experiments: Chun-Huan Li. Wrote the manuscript: Chun-Huan Li. Analyzed the data: Chun-Huan Li and Shi-Hong Luo. Evaluated the data and edited the manuscript: Sheng-Hong Li and Jin-Ming Gao. Contributed to discussion: Chun-Huan Li and Jin-Ming Gao.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 1–13 are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Cao L., Li Y., Li H., Liu D., Li R. New 3,4-seco-Grayanane Diterpenoids from the Flowers of Pieris japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016;64:1222–1225. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c15-00993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y., Liu Y.B., Yu S.S. Grayanoids from the Ericaceae family: Structures, biological activities and mechanism of action. Phytochem. Rev. 2013;12:305–325. doi: 10.1007/s11101-013-9299-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niu C.-S., Li Y., Liu Y.-B., Ma S.-G., Li L., Qu J., Yu S.-S. Analgesic diterpenoids from the twigs of Pieris formosa. Tetrahedron. 2016;72:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.09.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X., Gao L., Li Y., Li H., Liu D., Liao X., Li R. Highly Oxygenated Grayanane Diterpenoids from Flowers of Pieris japonica and Their Structure-Activity Relationship of Antifeedant Activity Against Pieris brassicae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:4456–4463. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Im N.-K., Zhou W., Na M., Jeong G.-S. Pierisformoside B exhibits neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in murine hippocampal and microglial cells via the HO-1/Nrf2-mediated pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015;24:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W.G., Li H.M., Li H.Z., Wu Z.Y., Li R.T. New grayanol diterpenoid and new phenolic glucoside from the flowers of Pieris formosa. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2010;12:70–75. doi: 10.1080/10286020903436519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S.J., Lin S., Zhu C.G., Yang Y.C., Li S.A., Zhang J.J., Chen X. G., Shi J. G. Highly Acylated Diterpenoids with a New 3,4-Secograyanane Skeleton from the Flower Buds of Rhododendron molle. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1560–1563. doi: 10.1021/ol1002797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Z.Y., Li H.Z., Wang W.G., Li H.M., Chen R., Li R.T., Luo H.R. Lyonin A, a new 9,10-Secograyanotoxin from Lyonia ovalifolia. Chem. Biodivers. 2011;8:1182–1187. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y., Liu Y.-B., Zhang J.-J., Li Y.-H., Jiang J.-D., Yu S.-S., Ma S.-G., Qu J., Lv H.-N. Mollolide A, a Diterpenoid with a new 1, 10:2,3-disecograyanane skeleton from the roots of Rhododendron molle. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3074–3077. doi: 10.1021/ol401254e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L.-Q., Chen S.-N., Cheng K.-F., Li C.-J., Qin G.-W. Diterpene glucosides from Pieris formosa. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:847–852. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke J.W., Doskotch R.W., Ni C.Z., Clardy J. Kalmanol, a pharmacologically active diterpenoid with a new ring skeleton from Kalmia angustifolia L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:5831–5833. doi: 10.1021/ja00197a050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou S.-Z., Yao S., Tang C., Ke C., Li L., Lin G., Ye Y. Diterpenoids from the flowers of Rhododendron molle. J. Nat. Prod. 2014;77:1185–1192. doi: 10.1021/np500074q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M., Zhu Y., Zhan G., Shu P., Sa R., Lei L., Xiang M., Xue Y., Luo Z., Wan Q. Micranthanone A, a new diterpene with an unprecedented carbon skeleton from Rhododendron micranthum. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3094–3097. doi: 10.1021/ol401292y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y., Liu Y.-B., Liu Y.-L., Wang C., Wu L.-Q., Li L., Ma S.-G., Qu J., Yu S.-S. Mollanol A, a diterpenoid with a new C-nor-D-homograyanane skeleton from the fruits of Rhododendron molle. Org. Lett. 2014;16:4320–4323. doi: 10.1021/ol5020653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y., Liu Y.-B., Yan H.-M., Liu Y.-L., Li Y.-H., Lv H.-N., Ma S.-G., Qu J., Yu S.-S. Rhodomollins A and B, two Diterpenoids with an Unprecedented Backbone from the Fruits of Rhododendron molle. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep36752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L.-Q., Qin G.-W., Chen S.-N., Li C.-J. Three diterpene glucosides and a diphenylamine derivative from Pieris formosa. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:779–787. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(01)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu C.-S., Li Y., Liu Y.-B., Ma S.-G., Liu F., Li L., Xu S., Wang X.-J., Wang R.-B., Qu J. Pierisketolide A and Pierisketones B and C, Three Diterpenes with an Unusual Carbon Skeleton from the Roots of Pieris formosa. Org. Lett. 2017;19:906–909. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J., Zhan G., Zhang H., Zhang Q., Li Y., Xue Y., Yao G. Rhodomollanol A, a Highly Oxygenated Diterpenoid with a 5/7/5/5 Tetracyclic Carbon Skeleton from the Leaves of Rhododendron molle. Org. Lett. 2017;19:3935–3938. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L.Q., Chen S.N., Qin G.W., Cheng K.F. Grayanane diterpenoids from Pieris formosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1473–1475. doi: 10.1021/np980180e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C.-H., Niu X.-M., Luo Q., Xie M.-J., Luo S.-H., Zhou Y.-Y., Li S.-H. Novel polyesterified 3,4-seco-grayanane diterpenoids as antifeedants from Pieris formosa. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2426–2429. doi: 10.1021/ol1007982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L.Q., Ding B.Y., Zhao W.M., Qin G.W. Grayanane diterpenoids from Pieris formosa. Chin. Chem. Lett. 1998;9:465–467. doi: 10.1021/np980180e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L.-Q., Ding B.-Y., Qin G.-W., Lin G., Cheng K.-F. Grayanoids from Pieris formosa. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:2045–2048. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00410-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z.Y., Li H.Z., Wang W.G., Li X.L., Li R.T. Secopieristoxins A and B, two unusual diterpenoids with a new 9,10-secograyanane skeleton from the fruits of Pieris formosa. Phytochem. Lett. 2012;5:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2011.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W.G., Wu Z.Y., Chen R., Li H.Z., Li H.M., Li Y.D., Li R.T., Luo H.R. Pierisformotoxins A–D, Polyesterified Grayanane Diterpenoids from Pieris formosa and Their cAMP-Decreasing Activities. Chem. Biodivers. 2013;10:1061–1071. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201200046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z.Y., Li Y.D., Wu G.S., Luo H.R., Li H.M., Li R.T. Three New Highly Acylated 3,4-seco-Grayanane Diterpenoids from the Fruits of Pieris formosa. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011;59:492–495. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hikino H., Ogura M., Fushiya S., Konno C., Takemoto T. Stereostructure of asebotoxin VI, VIII, and IX, toxins of Pieris japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1977;25:523–524. doi: 10.1248/cpb.25.523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S., Lin S., Zhu C., Yang Y., Li S., Zhang J., Chen X., Shi J. Highly acylated diterpenoids with a new 3,4-secograyanane skeleton from the flower buds of Rhododendron molle. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1560–1563. doi: 10.1021/ol1002797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Z.Y., Li H.M., Li Y.D., Li H.Z., Li R.T. Highly Acylated 3,4-Secograyanane Diterpenoids from the Fruits of Pieris formosa. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2011;94:1283–1289. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201000422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katai M., Fujiwara M., Terai T., Meguri H. Studies on the Constituents of the Leaves of Pieris japonica D. DON. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1980;28:3124–3126. doi: 10.1248/cpb.28.3124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou C., Li X., Li H., Li R. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Craibiodendron yunnanens. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012;45:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2012.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li C.H., Jing S.X., Luo S.H., Shi W., Hua J., Liu Y., Li X.N., Schneider B., Gershenzon J., Li S.H. Peltate Glandular Trichomes of Colquhounia coccinea var. mollis Harbor a New Class of Defensive Sesterterpenoids. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1694–1697. doi: 10.1021/ol4004756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C.H., Liu Y., Hua J., Luo S.H., Li S.H. Peltate glandular trichomes of Colquhounia seguinii harbor new defensive clerodane diterpenoids. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014;56:928–940. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo S.H., Luo Q.A., Niu X.M., Xie M.J., Zhao X., Schneider B., Gershenzon J., Li S.H. Glandular Trichomes of Leucosceptrum canum Harbor Defensive Sesterterpenoids. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2010;49:4471–4475. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D.-M., Zhang C.-C., Zhang Q., Shafiq N., Pescitelli G., Li D.-W., Gao J.-M. Wightianines A-E, Dihydro-beta-agarofuran Sesquiterpenes from Parnassia wightiana, and Their Antifungal and Insecticidal Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62:6669–6676. doi: 10.1021/jf501767s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.