Abstract

Hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) are heterodimeric transcription factors that regulate a number of adaptive responses to low oxygen tension. They are composed of α- and β-subunits that belong to the basic helix–loop–helix-PAS (bHLH-PAS) superfamily. In our efforts to identify new bHLH-PAS proteins, we cloned a cDNA encoding a novel α-class hypoxia inducible factor, HIF3α. The HIF3α open reading frame encodes a 662-amino acid protein with a predicted molecular weight of 73 kDa and is expressed in adult thymus, lung, brain, heart, and kidney. The N-terminal bHLH-PAS domain of this protein shares amino acid sequence identity with that of HIF1α and HIF2α (57% and 53% identity, respectively). The C-terminus of HIF3α contains a 36-amino acid sequence that shares 61% identity with the hypoxia responsive domain-1 (HRD1) of HIF1α. In transient transfections, this domain confers hypoxia responsiveness when linked to a heterologous transactivation domain. In vitro studies reveal that HIF3α dimerizes with a prototype β-class subunit, ARNT, and that the resultant heterodimer recognizes the hypoxia responsive element (HRE) core sequence, TACGTG. Transient transfection experiments demonstrate that the HIF3α-ARNT interaction can occur in vivo, and that the activity of HIF3α is upregulated in response to cobalt chloride or low oxygen tension.

Keywords: Hypoxia inducible factor, HIF3α, Molecular characterization

HYPOXIA inducible factors (HIFs) regulate tran-scriptional responses to low oxygen tension and other physiological conditions that rely upon glucose for cellular ATP (7). The HIF complex is a heterodimer of α-class and β-class subunits, both of which are members of the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH)-PAS superfamily (18). Proteins in the α-class, such as HIF1α and HIF2α, function as sensors, and their expression levels are rapidly upregulated by cellular hypoxia, treatment with iron chelators, or exposure to certain divalent cations like Co2+ (10,24,26,27). In contrast, the β-subunits are expressed constitutively and are ready to pair with their α-class partners in the nucleus (6,28). Recent evidence suggests that the bHLH-PAS proteins aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), ARNT2, and MOP3 can all act as β-class HIF subunits (9,10,27). A number of well-characterized HIF-responsive gene products have been identified including those encoding erythropoietin (EPO), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) (7,19,20). The promoters of these genes are regulated by hypoxia responsive elements (HREs) that are recognized by the HIF heterodimer. The HRE contains the core TACGTG element and has been found both 5′ and 3′ to the regulated promoter in a number of hypoxia-responsive genes (5,20).

Our laboratory is attempting to understand how bHLH-PAS proteins signal, as well as the biological consequences that result from cross-talk between pathways that share common subunits. The recent generation of thousands of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) has provided the opportunity to identify orphan bHLH-PAS proteins based upon nucleotide sequence similarity with known members of this emerging superfamily of transcription factors (1,10). As a result of this strategy, we now report the cloning and characterization of a novel bHLH-PAS protein, HIF3α, that meets the major criteria of an α-class HIF subunit. The observation that multiple α and β HIF subunits are encoded by the mammalian genome suggests that transcriptional responses to hypoxic stress result from an array of interactions that are more complex than previously perceived (10,26,27).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gel-Shift Oligonucleotides (the HRE Core Sequence Is Underlined)

OL396 TCGAGCTGGGCAGGTAACGTGGCAAGGC

OL397 TCGAGCCTTGCCACGTTACCTGCCCAGC

OL398 TCGAGCTGGGCAGGTGACGTGGCAAGGC

OL399 TCGAGCCTTGCCACGTCACCTGCCCAGC

OL414 TCGAGCTGGGCAGGGTACGTGGCAAGGC

OL415 TCGAGCCTTGCCACGTACCCTGCCCAGC

PCR Oligonucleotides

OL1014 GCCATGGCGTTGGGGCTGCAG

OL1017 ACTGTGTCCAATGAGCTCCAG

OL1178 GCCTCCATCATGCGCCTCACAATCAGC

OL1210 CCCCGTTACTGCCTGGCCCTTGCTCA

OL1323 AGCCGAGGGGGTCTGCGAGTATGTTGC

OL1324 GCTGCTGACCCTCGCCGTTTCTGTAGT

OL1397 GTCGACGCCACCATGGACTGGGACCAAGACAGG

OL1427 GGATCCTCAGTGGGTCTGGCCCAAGCC

OL1548 GCGGGGTGCTGGGAGTGGCTGCTAC

OL1698 GCCTTCCTGCACCCGCCTTCCCTGAG

OL1769 GCGGCCGCAAAAAACAAGACCGTGGAGACA

OL1771 GCCCTGGGAGAATAGCTGTTGGACTTTGGGCAATTGCTCACT

OL1772 GCGGCCGCCTATTCTGAAAAGGGGGGAAA

AP1 CCATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC

AP2 ACTCACTATAGGGCTCGAGCGGC

Cloning of HIF3α

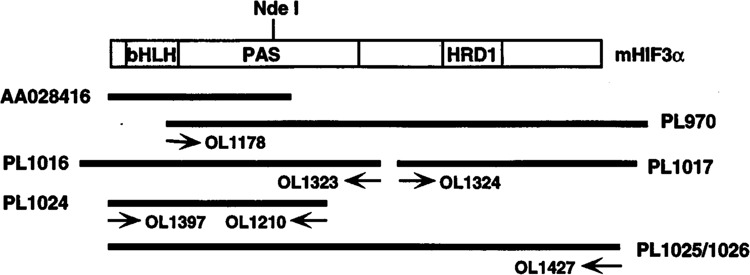

TBLASTN and BLASTX algorithms were used to search nucleotide sequences corresponding to amino acids 54 to 125 of hHIF1α in July of 1997 (http://dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu:9331/seq-search/Options/blast.html) (12). One mouse EST clone (GenBank AA028416, PL773) was found to encode a novel bHLH-PAS protein. To obtain the complete open reading frame (ORF), we performed a series of PCR amplifications using primer-anchored cDNA derived from mouse lung (“Marathon-Ready,” Clontech) (23). A 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) reaction was performed using oligonucleotides OL1178 and anchor primer API. The product of this PCR reaction was reamplified in a second reaction with OL1178 and AP2. The 2.0-kb 3′ PCR product obtained by this protocol was cloned into the pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega) and designated PL970. The clone was sequenced and found to contain an ORF followed by a translational stop site (Fig. 1). To confirm the position of this translational stop site, OL1324 was used in an independent 3′ RACE reaction. The 0.9-kb product was cloned into pGEM-Teasy vector (PL1017) and was found to contain the same stop codon (Fig. 1). To obtain the 5′ end of the cDNA, OL1323 was used in a RACE reaction against oligonucleotide API. The 1.2-kb RACE product was cloned into pGEM-Teasy vector (PL1016) and found to contain a translation start codon ATG followed by a long open reading frame. We define the nucleotide A from the initiation codon as position 1 of the cDNA. In addition, the translational start site is defined by the presence of an in-frame stop codon 51 nucleotides upstream. To generate expression plasmids containing the full ORF, a PCR reaction was performed using OL1210 and OL1397 with PL1016 as template. The PCR fragment was cloned into pGEM-Teasy vector in the SP6 orientation and named PL 1024. The NdeI fragment from PL 1024 was then inserted into the NdeI digested PL970 to generate the full-length HIF3α in the pGEM-Teasy vector (PL 1025).

FIG. 1.

Cloning of HIF3α. The positions of the original EST clone (AA028416) and the RACE products are shown as dark lines with the mHIF3α ORF shown as an open box. The PCR primers used are posted below the corresponding fragments and the plasmid number are marked on the side. The GenBank accession number for mHIF3α cDNA is AF060194.

Construction of HIF3α Expression Plasmids

For HIF3α expression in mammalian cells, the ORF was amplified by PCR using OL1397 and OL1427 with PL1025 as template. The resultant fragment was cloned into pTarget vector downstream of the CMV promotor (Promega) and was named PL1026 (Fig. 1).

To confirm the hypoxia inducibility of HIF3α, we constructed a fusion protein comprised of the DNA binding domain from GAL4 (residues 1–147), the predicted hypoxia responsive domain-1 (HRD1) from mHIF3α (residues 453–196), and the transactivation domain (TAD) from hARNT (residues 581–789). The HRD1 was amplified using OL1769 and OL1771 with mHIF3α as template. To form the HRD1/TAD chimera, the resultant PCR fragment from above was used as a megaprimer in a second PCR reaction with OL1772 as the second primer and hARNT as the template (2). The HRD1/TAD chimeric fragment was cloned into the NotI site of the GAL4 fusion vector pBIND (Promega) and designated PL1131.

Structural Gene Analysis and Chromosomal Localization

The HIF3α insert from PL773 was cut with EcoRI/NdeI and the 0.6-kb fragment was purified and used as probe to screen for BAC clones containing the mouse HIF3α gene (Genome Systems Inc.) (22). Oligonucleotides derived from the mHIF3α sequence were used as primers to sequence the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) DNA, and the splice sites were deduced by comparing the genomic and cDNA sequences. To obtain BACs containing the human HIF3α, oligonucleotides OL1014 and OL1017 were used in a PCR reaction with human heart cDNA as template (Clontech) to amplify a HIF3α fragment (Genbank accession number AF079154). This fragment was subcloned into the pGEM-Teasy vector, confirmed by sequencing, and used as a probe to screen for a BAC clone harboring the human structural gene for HIF3α as above. The identity of the resultant BAC was confirmed by direct sequencing using primers specific for hHIF3α. The human HIF3α chromosomal location was identified by PCR reactions against human/hamster somatic cell hybrid DNA using human HIF3α-specific oligonucleotides. This location was confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using the BAC harboring human HIF3α structure gene as the probe (Genome Systems Inc.) (25).

Northern Blot Analysis

To generate a hybridization probe for Northern blot analysis, a 0.9-kb HIF3α insert from PL1017 (Fig. 1) was excised with EcoRI and radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP by random priming (4). A Northern blot containing poly(A)+ mRNA from different mouse tissues (Origene Technologies) was hybridized with 5 × 106 cpm/ml HIF3α probe as previously described (15). β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Gel-Shift Assay

The core HRE element was generated by end-labeling 50 ng of oligonucleotide OF414 with [α-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol, DuPont NEN) and then annealing with 10-fold excess of unlabeled complementary oligonucleotide, OL415 (15). Unlabeled oligonucleotides containing either wild-type HRE sequence (TACGTG) or mutant HRE sequences, AACGTG (OF396/397) or GACGTG (OL398/399), were used in competition experiments to demonstrate specificity. For expression of the bHLH-PAS proteins, mHIF3α (PL1025) and hARNT (PL87) were synthesized in a reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine (3). The amount of each protein synthesized was calculated by measuring [35S]methionine radioactivity and estimated to be approximately 1 fmol in each 10 μl gel-shift reaction. Each gel-shift assay was performed with 100,000 cpm of oligonucleotide probe per 10 μl reaction (15). To confirm complex identity, 1 μl of anti-ARNT sera was used to alter the migration of the DNA–bound protein complex (16).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Mammalian expression plasmids expressing mHIF3α (PL1026) or hARNT (PL87) were transfected with the HRE-driven luciferase reporter PL945 (3,11). In order to document the activity of the GAL4/HRD1/TAD fusion protein, expression plasmid PL1131 was cotransfected with a luciferase reporter driven by five GAL4 DNA binding sites (pG5luc, Promega). Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine (GIBCO BRL Life Technologies). In all experiments, a β-galactosidase expression plasmid was cotransfected to control for transfection efficiency. Cells were incubated for 24 h in the presence or absence of 100 μM cobalt chloride or hypoxia (1% O2) before harvest (10). The luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined using the luciferase assay (Promega) and the Galacto-Light protocols (TROPIX Inc.), respectively (10).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

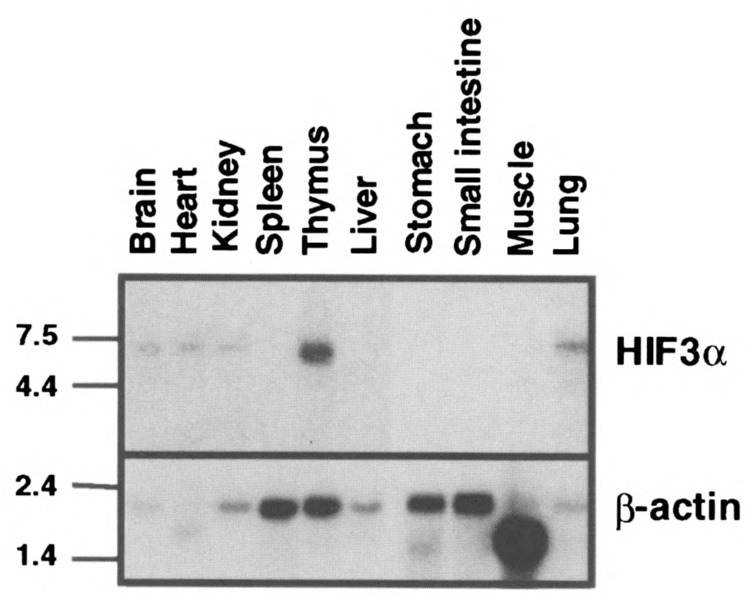

From a TBLASTN search of the dBEST database with the sequence corresponding to amino acid residues 54 to 125 of hHIF1α we identified a mouse EST clone (AA028416) that appeared to be a novel bHLH-PAS protein. In accordance with our earlier work, we initially referred to this protein as MOP7 (10). Based upon the results described below, we now refer to this protein as HIF3α. To obtain the complete ORF frame of this cDNA, a series of RACE reactions was performed using cDNA from mouse lung as template. The HIF3α ORF spans 1.98 kb and encodes a 662-amino acid protein with a predicted molecular weight of 73 kDa (Fig. 2). Northern blot analysis on mRNA prepared from selected mouse tissues identified a 7.2-kb HIF3α transcript that is expressed in adult thymus, lung, brain, heart, and kidney (Fig. 3). This expression pattern is distinct from that reported for other α-class HIFs. HIF1α is most abundantly expressed in kidney and heart, and HIF2α is most abundantly expressed in vascular endothelial cells and is highest in lung, placenta, and heart (10).

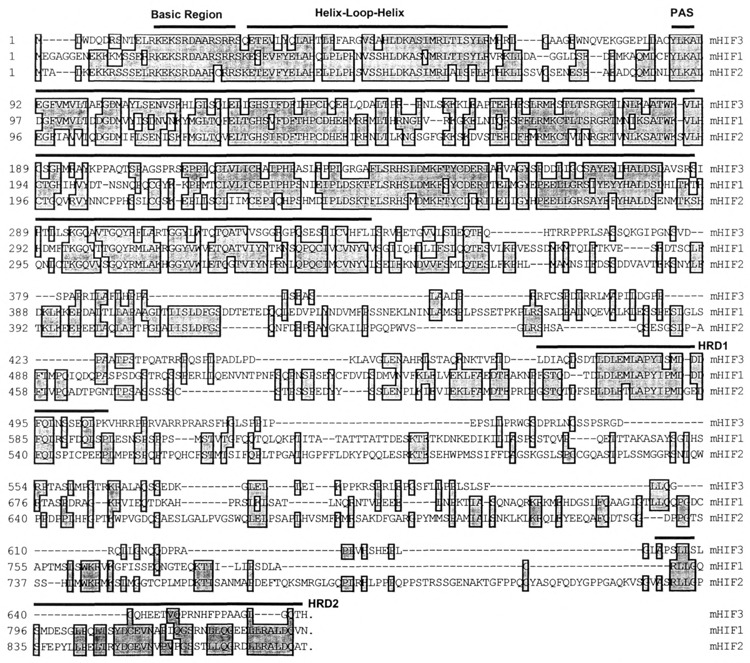

FIG. 2.

Alignment of three HIFs. The amino acid sequence of mouse HIF3α is aligned with that of mouse HIF1α and HIF2α using the CLUSTAL method. The positions of amino acids are shown on the left side. The basic region (BR), helix–loop–helix (HLH), PAS, and the hypoxia-responsive domains (HRDs) are marked with dark lines above the sequence. Conserved residues are boxed and in light gray.

FIG. 3.

Northern Blot analysis of HIF3α. Poly(A)+ (2 μg) RNA from each mouse tissue was loaded in each lane and hybridized with either HIF3α (upper panel) or β-actin (lower panel) probe as described in Materials and Methods. The molecular weight marker is shown on the left side.

HIF1α is the most well-characterized α-class sub-unit. This protein can be described by a number of signature motifs. In addition to the well-described bHLH-PAS domains, HIF1α also contains two HRD motifs in its C-terminus that confer hypoxia responsiveness. The HRD1 appears to primarily confer hypoxia-dependent protein stability whereas HRD2 appears to confer hypoxia-responsive transcriptional activity (13,17). In an effort to determine if similar motifs occur in HIF3α, we compared HIF1α, HIF2α, and HIF3α protein sequences using the CLUSTAL algorithm (8) (Fig. 2). We observed that these three HIF amino acid sequences shared greater than 92% identity in the basic region, 68% in the HLH domain, and greater than 53% in the PAS domain. Although little sequence with significant homology to HRD2 was found, a 36-amino acid stretch within the C-terminal half of HIF3α was found to share 61% identity with the HRD1 of HIF1α (13,14,17).

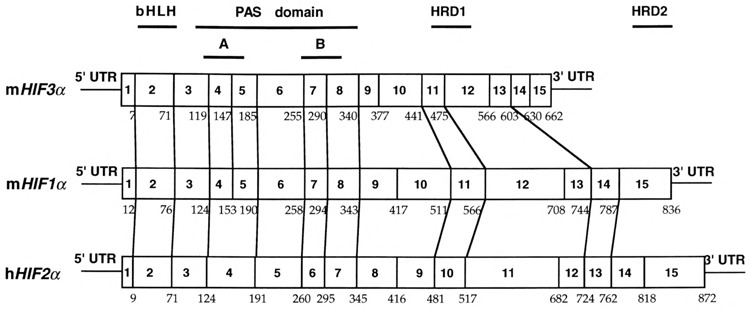

To further demonstrate the evolutionary relationship between these α-class HIFs, we compared their gene structure and chromosomal localization (15,26). Direct sequencing of a BAC clone containing the mHIF3α gene revealed 15 exons, all with consensus splice donor/acceptor sites (see sequences of Gen-Bank accession number AF079140-079153 for exon–intron junctions). We found that 11 of 15 and 10 of 15 splice junctions found in the mHIF3α gene are conserved to those found in the structural genes of mHIF1α and hHIF2α, respectively (Fig. 4). In an effort to characterize the distribution of HIF genes in the mammalian genome, we used human HIF3α-specific PCR reactions against a human/hamster somatic cell hybrid panel and mapped the HIF3α gene locus on human chromosome 19 (Fig. 5). This locus was further defined to chromosome 19q 13.13–13.2 by FISH using a BAC clone containing the human HIF3α structural gene as the probe (data not shown). Therefore, the human HIF3α locus is distinct from that of human HIF1α and HIF2α, which reside on chromosome 14q21-24 and 2p16-21, respectively [(21,26) and our unpublished results].

FIG. 4.

The splicing sites within mHIF3α ORF are compared with those previously reported for mHIF1α and hHIF2α. The numbers of amino acids at which the splicing occurs are marked underneath the sequence. The conserved splicing sites are defined as the splicing sites of HIF1α and HIF2α that are within one amino acid of the corresponding HIF3α splicing sites on the aligned sequence map using CLUSTAL method. These sites are marked with lines between different ORFs (see GenBank accession number AF079140-079153 for detailed sequences of mHIF3α splice sites).

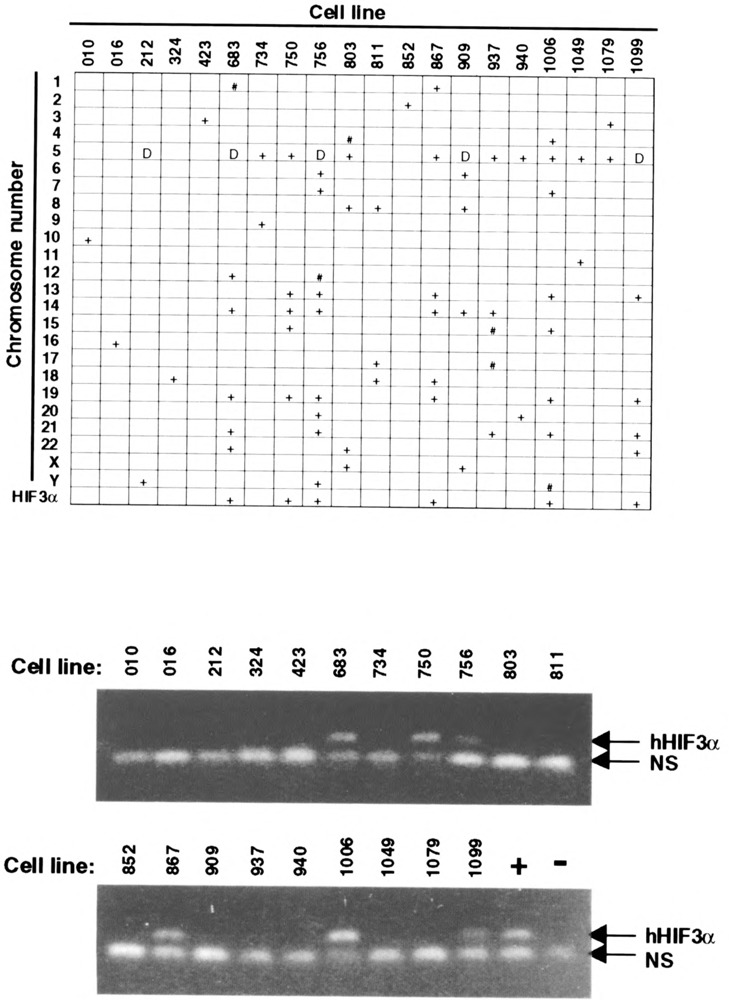

FIG. 5.

Chromosomal localization of HIF3α. Top: Chromosomal distribution in the somatic cell hybrid panel (BIOS Laboratories, CT). Cell lines and chromosomal number are marked on the axes. A “+” indicates > 30% of the cells contain the given chromosome; “#” indicates 5–30% of the cells contain the given chromosome; “D” indicates multiple deletions on the chromosome. The cell lines from which human HIF3α-specific PCR reaction are positive are also marked “+” in the last row. Bottom: HIF3α gene chromosomal localization via human HIF3α-specific PCR reaction. Human HIF3α-specific primers OL1548 and OL1698 were used for PCR reaction against genomic DNA from somatic cell hybrids. The expected 136-bp human HIF3α PCR product is marked. “NS” indicates nonspecific bands generated from the hamster genome. “+” and “−” indicate human and hamster genomic DNA served as positive and negative controls, respectively.

As a biochemical proof that HIF3α was a bona fide α-class HIF, we performed gel-shift and transient transfection analyses. Because HIF1α and HIF2α are known to pair with the β-class HIF sub-unit ARNT, we predicted that HIF3α would also pair with ARNT. Based upon sequence identity in their basic regions, we also predicted that a HIF3α–ARNT heterodimer would bind the HRE core sequence, TACGTG. In support of these predictions, the gel-shift analysis showed that HIF3α only bound to the HRE containing oligonucleotide in the presence of ARNT (Fig. 6). The specificity of the interaction was demonstrated by two additional observations. First, the HIF3α–ARNT–HRE complex was abolished by anti-ARNT IgGs but not by preimmune antibodies (Fig. 6). Second, the complex was blocked by an excess of HRE containing oligonucleotide, but not by oligonucleotides with a single mutation within the core HRE sequence (Fig. 6). To determine if this interaction could also occur in vivo, HIF3α and/or ARNT were cotransfected into COS-1 cells with a luciferase reporter driven by six HRE enhancer elements (11). The results demonstrated that the combination of HIF3α and ARNT upregulated transcription from the HRE-driven reporter by 11.7-fold, whereas neither protein alone had an effect. In addition, the activity of these complexes was enhanced by either hypoxia or cobalt chloride (Fig. 7A).

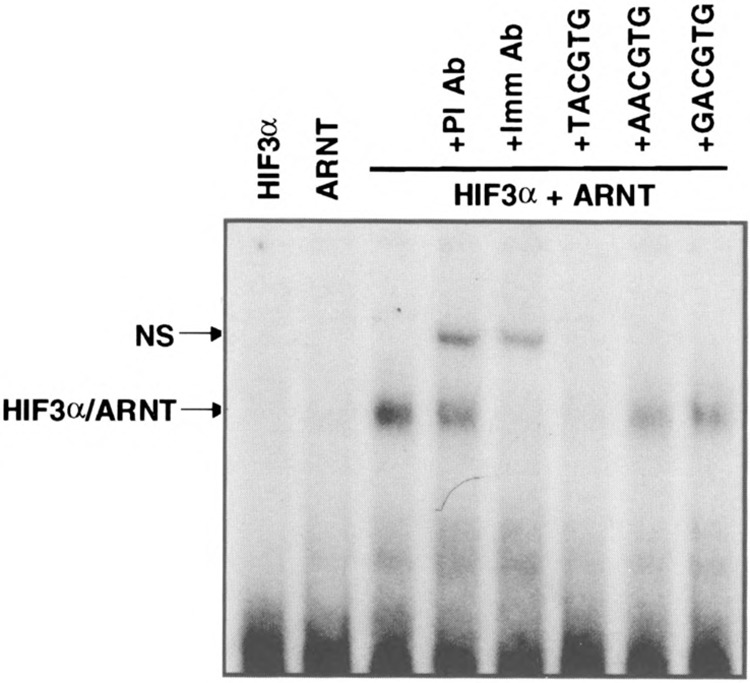

FIG. 6.

Gel-shift analysis of HIF3α. Radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe containing the HRE core sequence TACGTG was incubated with HIF3α and/or ARNT in the absence or presence of preimmune (PI) or immune (Imm) anti-ARNT antibody as described in Materials and Methods. For competition experiments, 400-fold of either wild-type (TACGTG) or mutant (AACGTG or GACGTG) oligonucleotides was added into each reaction. Specific (HIF3α/ARNT) and nonspecific (NS) complexes are marked.

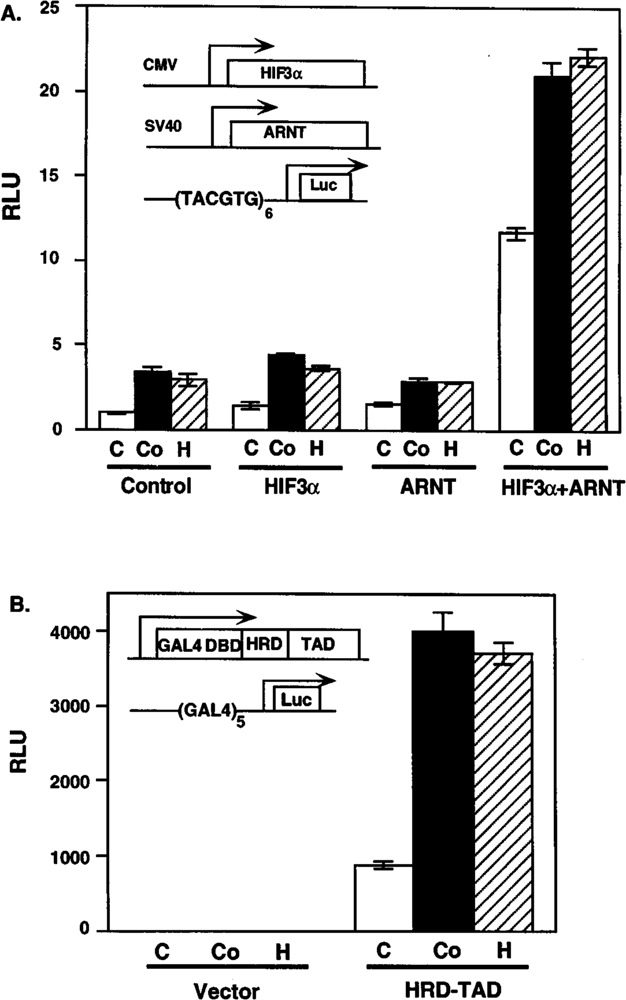

FIG. 7.

Transient transfection of HIF3α. (A) Interaction of HIF3α and ARNT in transiently transfected COS-1 cells. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing HIF3α and/or ARNT and a luciferase reporter driven by six HRE containing the TACGTG core sequence (inset). (B) Induction of HIF3α HRD1 domain by cobalt chloride and hypoxia treatment. Hep3B cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the GAL4/HRD/TAD fusion protein and a luciferase reporter driven by five GAM binding sites. The cells were treated without or with 100 μM CoCl2 or hypoxia (1% O2) for 20 h prior to harvest. Relative light units (RLU) were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Transfected expression plasmids and reporters are illustrated in the insets. The white, black, and striped columns represent control (C), cobalt chloride (Co), and hypoxia (H) treatments, respectively.

To demonstrate that the HIF3α activity was directly upregulated by hypoxia, we employed a fusion protein approach that has been used previously to map the HRDs of HIF1α (13,17). HRD1 of HIF1α has been shown to encode a hypoxia-responsive protein stability domain that also displays weak transcriptional activity. Given the sequence similarity between residues 453–496 of HIF3α and the HRD1 of HIF1α, we predicted that this domain would independently respond to hypoxic stimulus or Co2+ exposure. To test this idea, we constructed a plasmid expressing a fusion protein comprised of the DNA binding domain of GAL4, the predicted HRD1 of HIF3α, and the TAD from ARNT. We predicted that we could measure the response of this domain by monitoring the output from a GAL4-driven luciferase reporter in Hep3B cells (Fig. 7B). The results demonstrated that the fusion protein’s activity increased by 4.5-and 4.2-fold upon treatment with cobalt chloride or hypoxia, respectively (Fig. 7B). In control experiments, we observed that a GAL4 fusion protein harboring only the ARNT-TAD did not respond to either hypoxia or cobalt chloride treatment (data not shown). The level of inducibility seen with the HRD1 fusion is consistent with that obtained for a similar fusion protein using the HRD1 domain of HIF1α (17). This result provided evidence that amino acids 453 to 496 of HIF3α was sufficient to confer the hypoxia inducibility and that the stability of the parent protein is regulated in a manner that is similar to that of HIF1α and HIF2α (Fig. 7B).

In eukaryotes, transcriptional responses to low oxygen tension are mediated by complex interactions between a number of α-and β-class HIF subunits. The characterization of a third α-class HIF with a tissue distribution that is distinct from either HIF1α or HIF2α provides evidence that cellular responses to hypoxia result from a complex set of interactions from multiple combinations of α/β pairs. Our data also suggest that HIF3α may have a distinct role in mediating biological responses to hypoxia. In support of this idea, HIF3α and HIF1α have limited sequence homology in their C-termini. Most importantly, HIF3α contains sequence that corresponds to HIF1α’s protein stability element, HRD1, but not to its hypoxia-responsive TAD element, HRD2. Although the biological significance of this observation is not yet clear, it may indicate that HIF3α–ARNT complexes have decreased transcriptional potency relative to other HIF heterodimers. The importance of this complexity is underscored by the presence of HIF1α, HIF2α, and HIF3α in both mice and humans. Finally, this complexity appears to be highly conserved among vertebrates. In support of this idea, we have cloned a partial human HIF3α cDNA and have shown all three HIF α-class genes reside on separate human chromosomes and display considerable sequence divergence in their C-termini. Additional characterization of the developmental expression and genetic models of hypoxia derived from targeted disruptions of the individual α- and β-class HIFs should shed light on their relative physiological roles.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams M. D.; Kelley J. M.; Gocayne J. D.; Dubnick M.; Polymeropoulos M. H.; Xiao H.; Merril C. R.; Wu A.; Olde B.; Moreno R. F.; Kerlavage A. R.; McCombie W. R.; Venter J. C. Complementary DNA sequencing: Expressed sequence tags and human genome project. Science 252:1651–1656; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barik S.; Galinski M. S. “Megaprimer” method of PCR: Increased template concentration improves yield. Biotechniques 10:489–490; 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dolwick K. M.; Schmidt J. V.; Carver L. A.; Swanson H. I.; Bradfield C. A. Cloning and expression of a human Ah receptor cDNA. Mol. Pharmacol. 44:911–917; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feinberg A. P.; Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal. Biochem. 132:6–13; 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Forsythe J. A.; Jiang B. H.; Iyer N. V.; Agani F.; Leung S. W.; Koos R. D.; Semenza G. L. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:4604–4613; 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gradin K.; McGuire J.; Wenger R. H.; Kvietikova I.; Whitelaw M. L.; Toftgard R.; Tora L.; Gassmann M.; Poellinger L. Functional interference between hypoxia and dioxin signal transduction pathways: Competition for recruitment of the Arnt transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5221–5231; 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guillemin K.; Krasnow M. A. The hypoxic response: Huffing and HIFing. Cell 89:9–12; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higgins D. G.; Sharp P. M. CLUSTAL: A package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene 73:237–244; 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirose K.; Morita M.; Ema M.; Mimura J.; Hamada H.; Fujii H.; Saijo Y.; Gotoh O.; Sogawa K.; Fujii-Kuriyama Y. cDna cloning and tissue-specific expression of a novel basic helix-loop-helix/Pas factor (arnt2) with close sequence similarity to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (arnt). Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1706–1713; 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hogenesch J. B.; Chan W. C.; Jackiw V. H.; Brown R. C.; Gu Y.-Z.; Pray-Grant M.; Perdew G. H.; Bradfield C. A. Characterization of a subset of the basic-helix–loop–helix-PAS superfamily that interact with components of the dioxin signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272:8581–8593; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hogenesch J. B.; Gu Y.-Z.; Jain S.; Bradfield C. A. The basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5474–5479; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hwang D. M.; Hwang W. S.; Liew C. C. Single pass sequencing of a unidirectional human fetal heart cDNA library to discover novel genes of the cardiovascular system. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 26:1329–1333; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang B. H.; Zheng J. Z.; Leung S. W.; Roe R.; Semenza G. L. Transactivation and inhibitory domains of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Modulation of transcriptional activity by oxygen tension. J. Biol. Chem. 272:19253–19260; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li H.; Ko H. P.; Whitlock J. P. Induction of phosphoglycerate kinase 1 gene expression by hypoxia. Roles of Arnt and HIF1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21262–21267; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luo G.; Gu Y.-Z.; Jain S.; Chan W. K.; Carr K. M.; Hogenesch J. B.; Bradfield C. A. Molecular characterization of the murine HIF1-alpha locus. Gene Expr. 6:287–299; 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pollenz R. S.; Sattler C. A.; Poland A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein show distinct subcellular localizations in Hepa 1c1c7 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. Mol. Pharmacol. 45:428–438; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pugh C. W.; O’Rourke J. F.; Nagao M.; Gleadle J.; Ratcliffe P. J. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1; definition of regulatory domains within the alpha subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11205–11214; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Semenza G. L.; Agani F.; Booth G.; Forsythe J.; Iyer N.; Jiang B. H.; Leung S.; Roe R.; Wiener C.; Yu A. Structural and functional analysis of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Kidney Int. 51:553–555; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Semenza G. L.; Jiang B. H.; Leung S. W.; Passantino R.; Concordet J. P.; Make P.; Giallongo A. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 271:32529–32537; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Semenza G. L.; Nejfelt M. K.; Chi S. M.; Antonarakis S. E. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5680–5684; 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Semenza G. L.; Rue E. A.; Iyer N. V.; Pang M. G.; Kearns W. G. Assignment of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha gene to a region of conserved synteny on mouse chromosome 12 and human chromosome 14q. Genomics 34:437–439; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shizuya H.; Birren B.; Kim U.-J.; Mancino V.; Slepak T.; Tachiri Y.; Simon M. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor based-vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8794–8797; 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siebert P. D.; Chenchik A.; Kellogg D. E.; Lukyanov K. A.; Lukyanov S. A. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1087–1088; 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Srinivas V.; Zhu X.; Salceda S.; Nakamura R.; Caro J. Hypoxia-inducible factor la (HIF-la) is a non-heme iron protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18019–18022; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stokke T.; Collins C.; Kuo W. L.; Kowbel D.; Shadravan F.; Tanner M.; Kallioniemi A.; Kallioniemi O. P.; Pinkel D.; Deaven L.; et al. A physical map of chromosome 20 established using fluorescence in situ hybridization and digital image analysis. sGenomics 26:134–137; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tian H.; McKnight S. L.; Russell D. W. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 11:72–82; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang G. L.; Jiang B. H.; Rue E. A.; Semenza G. L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular 02 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5510–5514; 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wood S. M.; Gleadle J. M.; Pugh C. W.; Hankinson O.; Ratcliffe P. J. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) in hypoxic induction of gene expression. Studies in ARNT-deficient cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15117–15123; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]