Abstract

Purpose:

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. A decline in deaths caused by CRC has been largely attributable to screening and prompt treatment. Motivation, shown to influence cancer-related screening and treatment decisions, can be shaped by information from the Internet. The extent to which this information is easily readable on cancer-related websites is not known. The purpose of this study was to assess the readability levels of CRC information on 100 websites.

Methods:

Using methods from a prior study, the keyword, “colorectal cancer,” was searched on a cleared Internet browser. Scores for each website (n = 100) were generated using five commonly recommended readability tests.

Results:

All five tests demonstrated difficult readability for the majority of the websites.

Conclusions:

Online information related to CRC is difficult to read and highlights the need for developing cancer-related online material that is understandable to a wider audience.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, online information, readability

Introduction

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in women and men.[1] In 2018, it is expected that there will be 97,220 new cases of colon cancer and 43,030 new cases of rectal cancer, resulting in 50,630 deaths.[1] Early detection and treatment of CRC influence survival rates.[1] There has been a decline in deaths caused by CRC, which is largely attributable to screening and prompt treatment.[1] Motivation influences cancer screening and treatment decisions,[2] and both may be affected by the communications conveyed on the Internet.[3] The extent to which this information is readable and comprehendible can shape motivation and health-care decisions. A recent review of the literature suggests that effective health communication is multifaceted, and when health education efforts are ineffective, health can be impacted directly and/or indirectly.[4] Health education experts suggest that materials be written at the sixth-grade reading level for increased understandability,[5] but little is known about the extent to which this guidance is followed on websites related to cancer. The purpose of this study was to assess the readability levels of CRC information on 100 websites.

Methods

Methods, based on a prior study,[6] entailed searching a cleared Internet browser with the keyword “colorectal cancer.” The URLs of thefirst 100 websites written in English were included to create the sample. We then used readable.io, a Medline-recommended service, to generate readability scores for each website.[7] The service provides scores for five commonly recommended readability tests: Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index, Coleman–Liau Index, the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook Grade Level, and Flesch–Kincaid Reading Ease (FRE). We then grouped the scores and classified the readability as “easy” (grade <6), “average” (Grade 6–10), or difficult (Grade >10).

Results

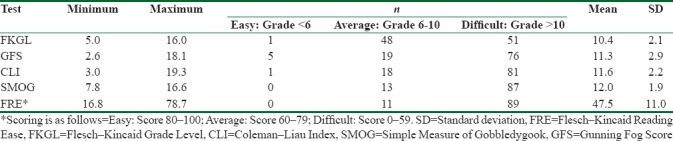

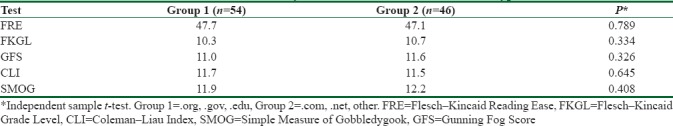

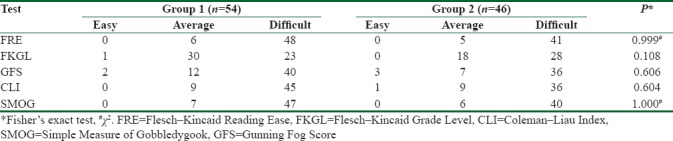

All five tests revealed that the majority of websites had difficult readability [Table 1]. Based on the FRE, 89% of the websites were graded as difficult and the remaining 11% were graded as average. All five tests showed that <6% of sites had easy readability. Among the four tests that determined readability based on grade level, all found the average grade to be above the 10th grade, which indicates difficult readability. There were no significant differences found between websites with.org., gov, or.edu extensions (Group 1) and those with.com., net, or other extensions (Group 2). Independent sample t-tests [Table 2] and Fisher's exact tests [Table 3] showed no significant differences in readability between the groups categorized based on their extension.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on the readability tests of all sites (n=100)

Table 2.

Mean readability scores based on website and URL type

Table 3.

Counts of easy, average, and difficult scores

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that, regardless of the URL type, online information related to CRC is difficult to read. Given that a facilitating factor for CRC screening is familiarity with CRC screening tests, increasing the ease with which materials can be read can lead to facilitating prevention efforts.[8] Study limitations include the cross-sectional design and restriction of material written in English. Nevertheless, this study supports the conclusion that cancer communications on the Internet are difficult to read[9] and highlights the need for developing health-related online material that is understandable to a wider audience. Further studies could explore the extent to which readability of materials influences one's motivations and actions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Colorectal Cancer. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html .

- 2.Basch CH, Basch CE, Wolf RL, Zybert P. Motivating factors associated with receipt of asymptomatic colonoscopy screening. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:20. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.152496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eysenbach G. The impact of the internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:356–71. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.6.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vahabi M. The impact of health communication on health-related decision making: A review of evidence. Health Educ. 2007;107:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenzie JF, Neiger BL, Thackeray R. New York: Pearson; 2016. Planning, Implementing & Evaluating Health Promotion Programs: A Primer. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basch CH, Ethan D, MacLean SA, Fera J, Garcia P, Basch CE. Readability of Prostate Cancer Information On-Line: A Cross-Sectional Study. American Journal of Men's Health. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1557988318780864. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. How to Write Easy-to_Read Materials. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html .

- 8.Brouse CH, Wolf RL, Basch CE. Facilitating factors for colorectal cancer screening. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:26–31. doi: 10.1080/08858190701818283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian C, Champlin S, Mackert M, Lazard A, Agrawal D. Readability, suitability, and health content assessment of web-based patient education materials on colorectal cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]