Abstract

A measles outbreak has been occurring in a healthcare setting in Porto, Portugal, since early March 2018, posing public health challenges for a central hospital and the community. Up to 22 April, 96 cases were confirmed, 67 in vaccinated healthcare workers, mostly between 18-39 years old. Following identification of the first cases, control measures were rapidly implemented. Concomitantly, other measles cases were notified in the Northern Region of the country. No common epidemiological link was identified.

Keywords: measles, Outbreaks, vaccines and immunisation, Healthcare workers

A tertiary level hospital in Porto with ca 4,400 healthcare workers (HCW) has been affected by a measles outbreak since March 2018, cases were mainly vaccinated HCW. As measles is a mandatory notifiable disease [1] in Portugal, the confirmation of the first cases on 14 March lead to the prompt implementation of public health control measures. We present preliminary findings of this outbreak, highlighting public health initial actions and their short-term results.

Case definition

In this outbreak, we started using the European Commission (EC) case definition [2]. Clinical criteria included any person with fever and maculopapular rash and any of the following three - cough, coryza, conjunctivitis. Possible cases were those meeting clinical criteria. Probable cases were those with clinical criteria and an epidemiological link (any connection with the hospital since February 2018). Confirmed cases were individuals not recently vaccinated and meeting the clinical/ epidemiological and laboratory criteria outlined in the EC case definition.

From 16 March, the case definition changed after we noticed atypical clinical presentation of measles in several individuals. Clinical criteria included any person with maculopapular rash, or fever and any of the following three symptoms: cough, coryza, conjunctivitis.

Outbreak description

On 13 March, the clinical director of a hospital in Porto reported a probable measles outbreak to the Public Health Regional Department (DSP), with 24 HCW affected. The local public health unit was then notified to assess and manage the situation, and initiated the epidemiological investigation. All cases had a connection to the adult Emergency Department (aED) and their clinical presentation included maculopapular rash, low fever, tachycardia and headache. The National Reference Laboratory, Instituto Nacional Dr. Ricardo Jorge, Lisbon, confirmed the first two cases on 14 March.

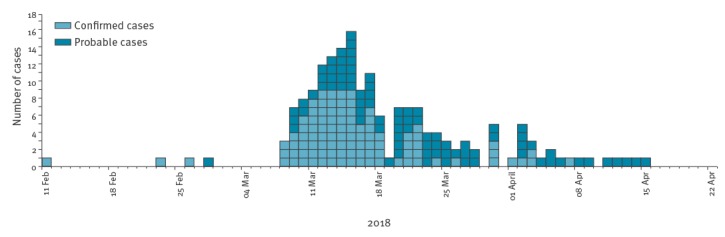

From 11 February to 22 April, 211 cases linked to the hospital were notified, with 96 confirmed cases (Figure).

Figure.

Confirmed cases of measles by day of symptom onset, Porto, Portugal, 11 February−22 April 2018 (n = 96)

In the same period, 405 cases were notified at the national level, with 109 confirmed cases [3].

Epidemiological investigation led to the retrospective identification of the earliest, the possible imported primary case: a young adult from a European country with circulating measles virus that arrived in Portugal ten days before the rash onset. The clinical case definition was met and laboratory results (positive IgM) confirmed the case. Genotype B3 was identified.

The mean age for the 211 cases notified was 33.3 (SD: 12.5), 135 cases were female. Preliminary findings showed that all but one confirmed measles cases (n = 96) occurred in adults (≥ 18 years; 18-39); 60 (62.5%) were female. Confirmed cases included 86 HCW (Table). One hospitalised patient was affected. Of the 96 confirmed cases, 67 (69.8%) were vaccinated with two doses of measles vaccine or measles mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

The last confirmed case had its rash onset on 9 April. No further cases have been identified linked to this hospital setting.

Table. Characteristics of measles cases by case classification, Porto, Portugal, 11 February−22 April 2018 (n = 211).

| Confirmed cases | Probable cases | Total number of notified cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 96 | 45.5 | 82 | 38.9 | 211 | 100.0 |

| Diagnostic site | ||||||

| CHP | 85 | 88.5 | 80 | 97.6 | 196 | 92.9 |

| Other | 11 | 11.5 | 2 | 2.4 | 15 | 7.1 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 60 | 62.5 | 52 | 63.4 | 135 | 64.0 |

| Male | 36 | 37.5 | 30 | 36.6 | 76 | 36.0 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 0–17 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 3.7 | 5 | 2.4 |

| 18–29 | 50 | 52.1 | 20 | 24.4 | 79 | 37.4 |

| 30–39 | 39 | 40.6 | 32 | 39.0 | 85 | 40.3 |

| 40–49 | 5 | 5.2 | 11 | 13.4 | 22 | 10.4 |

| 50–59 | 1 | 1.0 | 7 | 8.5 | 10 | 4.7 |

| 60–69 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.7 | 4 | 1.9 |

| 70–79 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 6.1 | 5 | 2.4 |

| 80–89 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Maculopapular rash | 84 | 87.5 | 63 | 76.8 | 147 | 69.7 |

| Fever and any of cough, coryza, conjunctivitis | 35 | 36.5 | 33 | 40.2 | 68 | 32.2 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||

| Confirmed in first analysis | 80 | 83.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 80 | 37.9 |

| Confirmed in second analysis a | 16 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 7.6 |

| Vaccination/immune status | ||||||

| No vaccination or measles history | 5 | 5.2 | 12 | 14.6 | 21 | 10.0 |

| One dose of measles vaccine | 11 | 11.5 | 14 | 17.1 | 29 | 13.7 |

| Two or more doses of measles vaccine | 67 | 69.8 | 44 | 53.7 | 126 | 59.7 |

| Presumptive immunity due to disease c | 2 | 2.1 | 2 | 2.4 | 5 | 2.4 |

| Unknown | 11 | 11.5 | 10 | 12.2 | 30 | 14.2 |

| Epidemiologic link | ||||||

| Without epidemiologic link b | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Non-HCW | 9 | 9.4 | 23 | 28.0 | 38 | 18.0 |

| HCW | 86 | 89.6 | 59 | 72.0 | 173 | 82.0 |

| Physicians | 31 | 36.0 | 13 | 22.0 | 49 | 28.3 |

| Nurses | 20 | 23.3 | 27 | 45.8 | 60 | 34.7 |

| Health technicians | 6 | 7.0 | 3 | 5.1 | 11 | 6.4 |

| Medical students | 12 | 14.0 | 5 | 8.5 | 19 | 11.0 |

| Nursing students | 5 | 5.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.9 |

| Support staff | 12 | 14.0 | 11 | 18.6 | 29 | 16.8 |

CHP: Centro Hospitalar do Porto; HCW: healthcare workers;

a For cases where the first laboratory confirmation samples were negative or not conclusive, second samples were necessary to exclude any false negatives or to exclude IgM false positive results in unvaccinated individuals through evidence of posterior seroconversion at about 10 days after the first laboratory analysis.

b Probably the primary case of the outbreak.

c Presumptive immunity due to disease: auto reported or documented previous measles infection.

Control measures

With the aim to control the outbreak in the hospital, decrease the number of secondary cases and minimise transmission into the community setting, an Emergency response team (ERT) was constituted. The ERT included hospital staff (clinical director, emergency department director, nurse director, occupational health team, infection control and prevention team and infectious disease physicians) and the local public health unit (local health authorities, public health physicians and nurses).

The hospital’s contingency plan was activated, and an isolation area was created to evaluate possible and probable cases in the aED. Precautions were instituted to prevent airborne transmission in the hospital, especially in departments with several cases. These precautions included the instalment of a portable laminar flow high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration system, the use of surgical masks, or P2/N95 respirators for HCW entering rooms with possible and probable cases. In addition, hand hygiene was strengthened.

All cases were advised to remain isolated for 4 days after they developed a rash. Medical clearance to return to work was given 5 days after the rash onset if there were no clinical complications from measles or if there were no continuing symptoms. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) [4,5] (vaccine or immunoglobulin) was offered within 72 hours to susceptible HCW and patients that had contact with a measles case. The regional stockpile of MMR vaccine and immunoglobulin allowed a rapid supply of these products. Two vaccination posts were created and HCW were advised to get vaccinated if they had not received two MMR doses in the past or a presumptive immunity due to disease; a total of 1,132 vaccines were administered.

For every possible or probable case in a HCW, the infection control and prevention team created a list of susceptible patients with whom the HCW may have had contact during their infectious period. Of more than 500 contacts identified, 73 patients received the MMR vaccine and 68 were immunised with immunoglobulin due to contraindications to vaccination or a high risk of severe illness and complications from being vaccinated.

As the outbreak occurred in a university hospital, medical and nursing schools were contacted and advised to inform students about the outbreak. Students were advised to verify their immunisation status and instructed to immediately report any symptoms within the measles case definition. Daily situation reports were released to HCW employed at the university hospital.

At the community level, local public health teams (from cases’ place of residency) performed case and contact investigation. Control measures included verification of immune status and PEP as well as symptom surveillance. If during case investigation the teams found any information relating to the hospital, they will send it to the ERT and they would manage it in the hospital setting.

At national level, DGS was responsible, among other aspects, to promote community engagement through short communications in media, three times a week reports and enforcing active epidemiological surveillance by alerting healthcare services in public and private health sectors.

Discussion

Several efforts have been made globally to eliminate measles [6-8], a highly contagious viral communicable disease that has the potential to infect 75–90% susceptible contacts [9] and is spread by airborne transmission [10].

Portugal had its last measles outbreak in 2017 following an imported case [11]. Prior to this, Portugal had 12 years without endemic measles transmission [11]. In the current outbreak, transmission of measles has occurred mainly in the healthcare setting. Proactive control measures were readily instituted which helped to control the outbreak and avoid a higher number of secondary cases in other settings. Measures included notification, isolation of cases, list of susceptible cases, contact tracing, screening for new cases and immunisation of susceptible population.

Vaccination or acquired immunity after illness are considered reliable protections against the disease [9]. Portugal is a country with a high level of reported vaccination coverage for MMR vaccine [12] and in 2017, MMR vaccine coverage at the age of 5 years was 96% [13]. According to the National Plan for Measles Elimination [14], HCW are highly recommended to receive two doses of MMR vaccine or documented evidence of measles infection, considering they are at a higher risk of exposure to the virus. Nevertheless, we are seeing outbreaks occurring that encompass healthcare settings [9,15]. The frequency of cases among HCW directs attention to the need of considering interventions to ensure this group is well protected, including vaccination and infection control and prevention measures.

Strikingly, most cases were in young (18-39 years old) fully vaccinated HCW. This feature has also been documented in other outbreaks [9,15]. The high frequency of cases among vaccinated people, likely due to waning vaccine-derived immunity [15] in a situation where natural boosting is taking place to a very limited extent, points towards the need to further investigate this issue to recommend new approaches. This is especially important for populations that are at a higher risk of being exposed to diseases, such as HCW, and spreading disease to individuals in a vulnerable situation, such as patients.

As we had our first case confirmation on 14 March and three cases started symptoms before March 2018, we had a delay between disease onset and confirmation of the diagnosis. This might have happened because Portugal has a low incidence of measles, therefore, HCW and clinicians do not commonly see measles in clinical practice and thus it may not have been their first diagnosis. In addition, atypical clinical presentation in vaccinated individuals could have been a contributing factor [16].

The atypical clinical presentation of measles in vaccinated individuals can occur with mild or moderate symptoms [17] similarly to our outbreak (maculopapular rash as the only clinical criteria or low fever). To ensure that as many cases were identified as possible during the outbreak, the case definition was adapted, increasing sensitivity, taking atypical presentation of measles into account.

In a country with low incidence of measles, this outbreak emphasises risks and challenges posed locally, such as infection of fully vaccinated individuals and the sustainability of herd immunity in a healthcare setting.

Further investigation of this outbreak is ongoing, including genotyping of all cases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following healthcare workers: Jorge Gonçalves, Teresa Cruz, medical residents and phyisicians from the Infectious Disease team, Sandra Xará, Sónia Almeida, Maria Conceição Costa, Maria do Céu Henriques, Patrocínia Rocha, Alexandra Fernandes, Occupational Health team, Idalina Beirão, Laura Marques, Guilherme Queiroz and general medical residents from CHP that helped the ERT during the outbreak. As this is a collaborative work, we would like to say thank you to all public health teams performing case and contact investigation, DSP, INSA and DGS.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contributions: Rita Sá Machado, Mariana Perez Duque, Ana Sottomayor, Ivo Cruz, Soraia Almeida, Júlio R. Oliveira and Isabel Almeida contributed to data collection, case information and data analysis.

Delfina Antunes coordinated the investigation of the outbreak.

Rita Sá Machado and Mariana Perez Duque drafted the manuscript, with contribution by Ana Sottomayor, Ivo Cruz e Soraia Almeida.

Delfina Antunes, Júlio R. Oliveira and Isabel Almeida were involved in revising the manuscript.

All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Republic of Portugal [Directorate-General of Health]. (DGS). Doenças de notificação obrigatória [Clinical and laboratory mandatory notification of diseases] Despacho n.° 15385-A/2016, Diário da República, 2ª série; 243, 21 dezembro de 2016. Lisbon: DGS; 21 Dec 2016. Portuguese. Available from: https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/105574339

- 2.European Commission. Commission Implementing Decision of 8 August 2012 amending Decision 2002/253/EC laying down case definitions for reporting communicable diseases to the Community network under Decision No 2119/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (notified under document C(2012) 5538). Official Journal of the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. 27.9.2012:L 262. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT /?uri=OJ%3AL%3A2012%3A262%3ATOC

- 3.Republic of Portugal – Directorate-General of Health (DGS). Boletim epidemiológico - Sarampo em Portugal. [Epidemiological Bulletin - Measles in Portugal]. Lisbon: DGS; Apr 2018. Portuguese. Available from: https://www.dgs.pt/em-destaque/sarampo-atualizacao-a-23-de-abril-pdf.aspx

- 4.Strebel PM, Papania MJ, Fiebelkorn AP, Halsey NA. (2013) Measles vaccine (Chapter 20). In: Vaccines 6th Edition (eds. Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA) Elsevier Saunders, pp. 352–387 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young MK, Nimmo GR, Cripps AW, Jones MA. Post-exposure passive immunisation for preventing measles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; (4):CD010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Measles and Rubella. Strategic Plan 2012-2020. Geneva: WHO; 2012. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44855/9789241503396_eng.pdf;jsessionid=21B25C70C9DF52B51343FC5B9471D8DE?sequence=1

- 7.Moss WJ, Griffin DE. Global measles elimination. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(12):900-8. 10.1038/nrmicro1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dabbagh A, Patel MK, Dumolard L, Gacic-Dobo M, Mulders MN, Okwo-Bele JM, et al. Progress Toward Regional Measles Elimination - Worldwide, 2000-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(42):1148-53. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6642a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia H, Ma C, Lu M, Fu J, Rodewald LE, Su Q, et al. Transmission of measles among healthcare Workers in Hospital W, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China, 2016. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):36. 10.1186/s12879-018-2950-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heymann DL, editor. Measles in Control of Communicable Disease Manual, 19th edition. Washington D.C: American Public Health Association; 2008. 402-409 [Google Scholar]

- 11.George F, Valente J, Augusto GF, Silva AJ, Pereira N, Fernandes T, et al. Measles outbreak after 12 years without endemic transmission, Portugal, February to May 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017;22(23):30548. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.23.30548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Republic of Portugal – Directorate-General of Health (DGS). Avaliação do programa nacional de vacinação e melhoria do seu custo-efetividade: 2.° inquérito serológico nacional: Portugal Continental 2001-2002. [Evaluation of the National Immunisation Programme and improvement of its cost- effectiveness: 2nd National Serological Survey – Continental Portugal 2001-2002]. Lisbon: DGS; 2004. Portuguese. Available from: www.dgs.pt/ficheiros-de-upload-1/2-inquerito-serologico-nacional-livro-pdf.aspx

- 13.Republic of Portugal – Directorate-General of Health (DGS).Boletim do Programa Nacional de Vacinação [National Immunisation Programme Bulletin]. Lisbon: DGS; May 2018. Portuguese. Available from: https://www.dgs.pt/documentos-e-publicacoes/avaliacao-do-programa-nacional-de-vacinacao-2017-pdf.aspx

- 14.Republic of Portugal – Directorate-General of Health (DGS). Programa Nacional para a Eliminação do Sarampo. [National Programme for Measles Elimination]. Lisbon: DGS; Mar 2013. Portuguese. Available from: https://www.dgs.pt/documentos- e-publicacoes/programa-nacional-de-eliminacao-do-sarampo- jpg.aspx.

- 15.Hahné SJ, Nic Lochlainn LM, van Burgel ND, Kerkhof J, Sane J, Yap KB, et al. Measles Outbreak Among Previously Immunized Healthcare Workers, the Netherlands, 2014. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(12):1980-6. 10.1093/infdis/jiw480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma R, Lu L, Zhangzhu J, Chen M, Yu X, Wang F, et al. A measles outbreak in a middle school with high vaccination coverage and evidence of prior immunity among cases, Beijing, P.R. China. Vaccine. 2016;34(15):1853-60. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry RT, Halsey NA. The clinical significance of measles: a review. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(s1) Suppl 1;S4-16. 10.1086/377712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]