Abstract

Intestinal involvement with disseminated histoplasmosis is common in some populations infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), especially in those who come from tropical zones. We report the case of a 29‐year‐old male patient, from a tropical zone, with HIV infection and a CD4 value less than 50 cells/mm3, with a history of abdominal pain, fever, diarrhea, and weight loss. On presentation, he was pale, sweaty, and had abdominal rebound tenderness. Laboratory findings demonstrated microcitic hipocromic anemia, azoemia, and hypoalbuminemia. Abdominal‐X‐rays revealed pneumoperitoneum and air fluid levels. He underwent surgery, and a 1‐cm perforation proximal to ileocecal valve was found. A resection and an ileostomy were performed. Histopathology identified caseating granulomas with yeast, compatible with histoplasmosis. He was treated with anfotericin B plus itraconazol with clinical improvement.

Keywords: histoplasmosis, human immunodeficiency virus, intestinal perforation

Introduction

There were approximately 60 000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐infected patients reported in Peru until 2015, of which roughly 56% were in the advanced stages (acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS]).1 Acute abdominal pain is a frequent cause of hospitalization in those patients. Montoya et al.2 reported a series of 1895 patients admitted to a public hospital in Lima, and 97 (5.1%) of these patients had acute abdominal pain, more frequently caused by tuberculosis, cholecystitis, and appendicitis (26%, 20%, and 13%, respectively). Perioperative mortality was more frequent in patients with high HIV‐RNA and low CD4 + counts.

Whitney et al.,3 reported 63 operations in HIV‐positive patients, appendicitis being the most frequent (34%). In addition, they found three intestinal perforations, one caused by lymphoma, one was iatrogenic, and the other of unknown etiology. Intestinal perforation in HIV‐positive patients has been reported in many cases, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, lymphoma, histoplasmosis, mycobacterium avium complex, Kaposi's sarcoma, appendicitis, peptic ulcer disease, and tuberculosis, among others.4

We report the case of an HIV‐infected patient who had an ileal perforation caused by histoplasmosis.

Case report

This is the case of a 29‐year old male from the Peruvian jungle who was HIV positive for about 6 years, has not been receiving highly active antiretroviral (HAART) therapy, and with a CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mm3. The patient complained of diffuse abdominal pain lasting for 1 month, subsequently localized to the right lower quadrant, with an intensity of 9/10, associated with fever, chronic diarrhea, and a 6‐kg weight loss. On physical examination, he looked chronically ill with pallor, and his abdomen had rebound tenderness on the right lower quadrant. Laboratory examinations showed severe hypochromic microcytic anemia, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and azotemia.

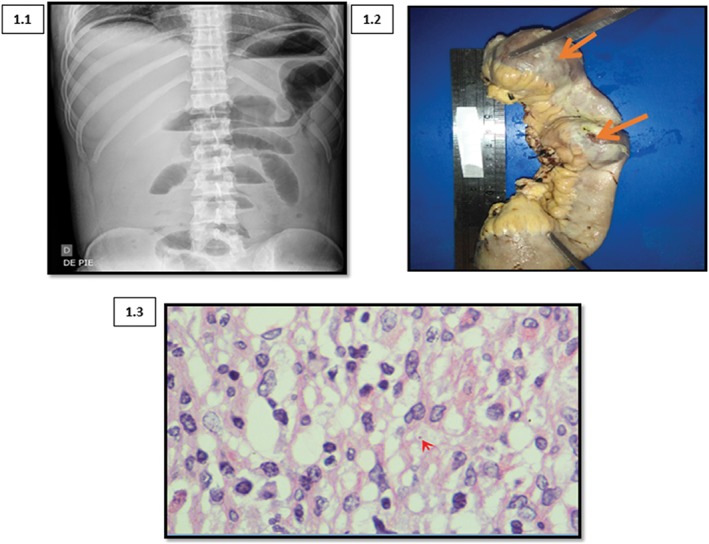

A flat abdominal X‐ray showed pnemoperitoneum and air fluid levels (Fig. 1a). He was taken to the operating room, where 1 L of pus and a 1 cm perforation, approximately 40 cm proximal to the ileo‐cecal valve, with ileal wall thickening were found. A segmental ileal resection and ileostomy were performed. The gross specimen in (Fig. 1b) shows the ulcer in the terminal ileum, and histopathological examination revealed the presence of caseating granuloma with yeast, compatible with histoplasmosis (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

(a) Abdominal X‐ray with pnemoperitoneum and air fluid levels. (b) Segment of small intestine. The large arrow indicates the location of the bowel perforation. The small arrow points to the fibrin layer that covers the intestinal serosa. (c) Hematoxylin–eosin (H–E) staining (400×) shows a macrophage with yeast of approximately 3 μm diameter, compatible with Histoplasma (arrow).

Therapy with amphotericin and itraconazole was started with a favorable response. The patient required hemodialysis for chronic kidney disease, probably due to HIV‐associated nephropathy (renal biopsy was not performed). It is important to remark that there was not any sign to suspect CMV infection.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in HIV‐positive patients should include opportunistic infections and neoplasms.2 Histoplasmosis is a systemic infection caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, which is found in soil contaminated with feces of birds or bats and enters the human body by inhaled spores, developing into different manifestations of disease.5 Histoplasmosis is the most common endemic mycosis in South America.5 Acute infection is frequently asymptomatic and typically affects the lungs; only 5% of the exposed developed symptoms. Some manifestations of the disease are acute, subacute, or chronic lung compromise; bronchiolitis; mediastinal lymphadenophaty; mediastinal granuloma or fibrosis; and ocular histoplasmosis.5

In an immunocompetent patient, cell‐mediated immunity controls the disease. T lymphocytes, gamma interferon, and tumor necrosis alpha control the disease, activating macrophages.5

The disseminated form occurs in 1 in 1000 acute infections, in patients who are unable to control the infection, and the risk increases 10‐fold in immunosupressed patients.5 The most common symptoms are fever, anorexia, asthenia, weight loss, and dyspnea. The physical exam shows lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and oral or skin lesions. Laboratory examination usually reveals anemia, leucopenia, and elevation of liver enzymes and bilirubin and lactic desidrogenase.5 The disseminated disease more frequently affects the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract.5

Flannery et al. reported histoplasmosis in 55% of their immunosupressed patients.6 In Peru, Tingo María, Iquitos, and Pucallpa are considered endemic areas, all located in the Amazonian region.7

Gastrointestinal involvement by histoplasmosis is reported in 70–90% of patients with disseminated disease, and it can involve any segment from the mouth to the anus, the ileo‐cecal area being the most frequently affected. Only 3–12% of patients present symptoms, and the most frequent are abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and weight loss.8

Endoscopically, the most frequent findings are: stenosis (the most common), solitary or multiple ulcers (up to 33% of cases), edema, or pseudopolyps (the least frequent).9

Most of the ulcers are multiple, annular, with raised edges associated with hyperemia, hemorrhage and necrotic base measuring from 0.2 to 4 cm in diameter.8

Pathological examination commonly demonstrates mucosal ulceration, diffuse lymphohystiocytic infiltrate, and hystiocytic nodules.8 The diagnostic yield of histology ranges from 50 to 75%.9 Cultures are positive in 50–85% of cases.5, 8, 9 Small cells (2–4 μm in diameter) can be seen inside macrophages.8 The best stain is Groccott Gömöri metanamine.8 In cases of massive infestation with yeast, they can be seen with PAS and H‐E.5, 8 Caseating granuloma can be observed, although well‐defined granulomas are reported in only 8% of cases.6, 8

The most frequent complications of gastrointestinal histoplasmosis are gastrointestinal bleeding and intestinal obstruction.8 There are rare cases described of intestinal perforation by H. capsulatum.7 Mortality in untreated disseminated histoplasmosis can reach 80%, but it can decrease to 25% with appropriate treatment.8

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends liposomal amphotericin (3 mg/kg per day) for 1–2 weeks, followed by itraconazole 200 mg tiD for 3 days and then 200 mg biD for at least 12 months for moderate to severe disseminated histoplasmosis given its better response and decreased mortality compared with amphotericin desosycholate (88 vs 64% and 2 vs 13%, respectively).10

The HIV‐positive patient we report comes from an endemic area and received the abovementioned treatment with a favorable response.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patient and his family who consented to the publication of the case details.

Declaration of conflict of interest: None.

Author contribution: Bellido‐Caparo A, Delgado‐Malaga S, Garcia‐Encinas C, Tagle‐Arrospide M contributed to the drafting of the case report. Bellido‐Caparo A, Garcia‐Encinas C, Espinoza‐Rios J, Cáceres‐Pizarro J, Tagle‐Arrospide M contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the case report.

Financial support: None.

References

- 1. Pun M. Situación de la epidemiología del VIH en el Perú. Lima: Dirección General de Epidemiología. MINSA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montoya L, Rodriguez E, Zuñiga G, Yamamoto G, Gonzales E. Abdomen Agudo en pacientes con VIH/SIDA atendidos en un Hospital Nacional de Lima Perú. Rev. Peru Med. Exp. Salud. Pública. 2014; 31: 515–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whitney TM, Brunel W, Russell TR, Bossart KJ, Schecter WP. Emergent abdominal surgery in AIDS: experience in San Francisco. Am. J. Surg. 1994; 168: 239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Slaven EM, Lopez F, Weintraub S, Mena JC, Mallon W. The AIDS patient with abdominal pain: a new challenge for the emergency physician. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am.. 2003; 21: 987–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr N, Spec A, Relich R. Histoplasmosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2016; 30: 207–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flannery M, Chapman V, Cruz I, Rivera M, Messina J. Ileal perforation secondary to Histoplasmosis in AIDS. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2000; 320: 406–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alva E, Vasquez J, Frisancho O, Yoza M, Yabar A. Histoplasmosis Colónica como manifestación diagnóstica de SIDA. Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 2010; 30: 163–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kahi C, Wheat J, Allen S, Sarosi G. Gastrointestinal histoplasmosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005; 100: 220–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cosme A, Pardo E, Felipo F, Iribrarren J. Abdominal pain in a HIV infected patient. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2005; 97: 196–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB et al Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007; 45: 807–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]