Abstract

Background

Lenalidomide is effective for the treatment of low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with deletion 5q abnormalities. However, whether lenalidomide leads to a significant improvement in treatment response and overall survival (OS) in cases of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains controversial. A systematic review and a meta-analysis were performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide in the treatment of AML.

Methods

Clinical studies were identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Efficacy outcomes included overall response rate (ORR), complete remission (CR), and OS. Safety was evaluated based on the incidence of grade 3 and 4 treatment-related adverse events (AEs).

Results

Eleven studies were included in our meta-analysis; collectively these studies featured 407 AML patients. Pooled estimates for overall ORR and CR were 31% (95% CI: 26%–36%) and 21% (95% CI: 16%–27%), respectively. Thrombocytopenia, anemia, neutropenia, and infection were the most common grade 3 and 4 AEs.

Conclusion

Lenalidomide may have some clinical activity in AML, but the population that would benefit from lenalidomide and incorporating lenalidomide into combination drug strategies need to be better defined.

Keywords: azacitidine, cytarabine, immunomodulatory agent, cytogenetic risk

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of hematological clonal disorders, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 25%.1–4 AML is also the most common acute leukemia in elderly patients. Approximately 20,000 new cases of AML are diagnosed per year in the US.1,2 According to 2010–2012 data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute, approximately 0.5% of males and females in the US will be diagnosed with AML at some point during their life. The incidence of AML increases with age, from ~1.3 cases per 100,000 in individuals <65 years of age tô12.2 cases per 100,000 individuals >65 years of age. AML is primarily a disease of elderly patients, with an estimated overall median age of approximately 70 years.5,6

Induction therapy with cytarabine and an anthracycline remains the standard of care for younger patients with AML (<60 years of age).7 Allogeneic stem cell transplantation has also been shown to improve outcomes among younger patients with intermediate- or high-risk cytogenetic AML.8–11 However, more than 70% of patients with AML are >60 years of age, and this excludes that strategy as a treatment option for the majority of patients with AML.12 Treatment options for elderly patients with AML who have a poor prognosis with a projected median overall survival (OS) of <1 year and a 5-year OS of 10%–20% are a considerable therapeutic challenge.13–15 Furthermore, in the US, less than 50% of subjects with AML over 65 years of age receive therapy within 3 months of diagnosis.16 The outcomes for patients with relapsed or refractory AML are even worse. Currently, there is no standard therapy for relapsed/refractory AML. Consequently, there is a clear need for new therapies for the treatment of AML that exhibit better efficacy and less toxicity, and permit an individualized approach to treatment.

Lenalidomide is a derivative of thalidomide, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for hematological malignancies. The mechanism of action for lenalidomide in AML is not completely understood, although it has been shown previously to reduce cell proliferation, enhance apoptosis, interrupt tumor-stroma interactions, and alter innate and adaptive immune responses.17 Several studies have investigated lenalidomide as a therapy for AML. For example, Blum et al showed that monotherapy with lenalidomide was clinically active for AML, with a complete remission (CR) of 16%.18 Fehniger et al further demonstrated that high-dose lenalidomide (50 mg/day), as an initial therapy in elderly AML patients, had a 30% combined CR/incomplete CR (CRi).19 However, a recent study showed that lenalidomide alone or sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide was no better than azacitidine alone in patients >65 years with newly diagnosed AML.20 Thus, whether lenalidomide improves treatment response in AML remains controversial. This meta- analysis was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide for the treatment of AML. Our analysis is based on a review of published clinical studies of AML patients treated with lenalidomide.

Materials and methods

Search methods and the selection of studies

A systematic review of data from eleven published studies was performed using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.21 Potentially eligible studies were identified by searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, Embase, and the ClinicalTrials.gov using a combination of subject headings and text words to identify relevant trials. The search was performed for clinical studies published from inception until January 2018. The PubMed search strategy included combinations of the following terms: {(“acute myeloid leukemia” OR “AML” OR “acute leukemias” OR “acute leukemia” OR “Leukemia, Myeloid, Acute” [MeSH]) AND [“lenalidomide” OR “Revlimid”]}. A very similar strategy was employed for the search of other databases. The reference lists of eligible trials and reviews were also evaluated for additional clinical data sources.

Two reviewers (CX and JH) independently screened studies for further inclusion in the meta-analysis. Prospective studies for meta-analysis were selected irrespective of blinding, language, publication status, date of publication, and sample size. Only studies that enrolled patients with a diagnosis of AML, consistent with the WHO classification for AML, were included in our meta-analysis. Data for patients treated with lenalidomide monotherapy, lenalidomide in combination with azacitidine, or lenalidomide in combination with cytarabine were evaluated in the meta-analysis. No dosage restriction was applied.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes for this meta-analysis were overall response rate (ORR) and CR. Outcomes were assessed according to the International Working Group response criteria for AML. CR was defined as following: <5% blasts in bone marrow, >1.0×109/L neutrophils, and >100×109/L platelets in peripheral blood without evidence of extramedullary leukemia.22,23 CRi was defined as a CR with incomplete recovery of peripheral blood counts.23 ORR comprised both CR and CRi. Secondary outcomes included OS, defined as the time from the start of treatment until death from any cause, and safety, which was evaluated based on the incidence of grade 3 and 4 treatment-related adverse events (AEs).

Data extraction

The two authors independently screened search outputs, identified eligible studies, examined outcomes, retrieved full texts, and assessed studies and data for inclusion. A standardized form was used to collect data and to assess the quality of the studies included in our analyses. The two authors extracted data independently. Missing data were requested from the study authors.

Risk of bias

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies was applied, with some adaptions, to evaluate the quality and risk of bias for all papers included in this systematic review.24 The two authors independently assessed the risk of bias for all studies. Where ten or more studies were identified for each outcome, publication bias was evaluated by the visual assessment of funnel plots.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using meta-analysis software “Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2.0” (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Statistical heterogeneity across studies was analyzed using the chi-squared test and I2 statistic; higher values indicated a greater degree of heterogeneity. This criterion was used to determine whether a fixed- or random-effects model was appropriate for subsequent data analysis. Estimated proportions with 95% CIs were calculated for all ratio outcomes.

Subgroup analysis for response rate was performed based on lenalidomide monotherapy or lenalidomide in combinations, cytogenetic risk, and AML type if relevant data were available.

Results

Search results

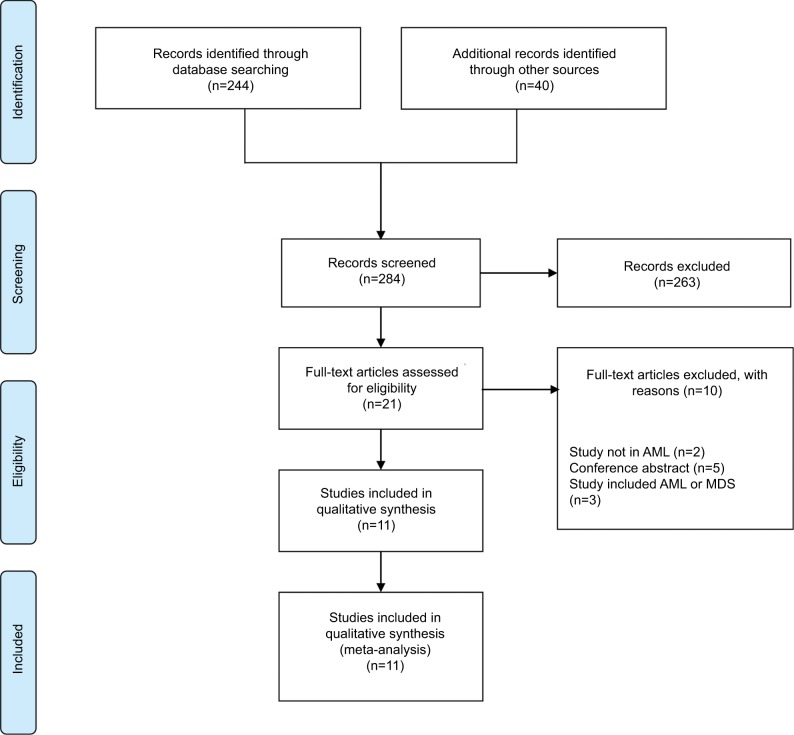

Our initial search yielded 284 articles. After exclusion, based on title and abstract, 21 full-text articles were reviewed and eleven observational studies were included.18–20,25–32 Screening of the reference lists for additional studies or referring articles did not yield any further articles for inclusion. Figure 1 shows a flowchart for study selection.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flowchart describing the literature search strategy and study selection.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS: myelodysplastic syndromes.

Study characteristics and the risk of bias

Overall, 407 participants took part in the eleven trials included in this meta-analysis.18–20,25–32 The studies included in this meta-analysis showed high variability in terms of the number of AML patients, ranging from 18 to 66. The median age for AML patients in these studies ranged from 63 to 76 years with the proportion of women ranging from 33% to 57%. The characteristics of the studies included in our meta- analysis are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis

| Study | No. ofpatients | Medianage inyears(range) | Gender(%female) | Treatment scheme | BM blast(%) | Previous treatmentwith eitherchemotherapy orHMAs | AML type | Overall survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blum et al (2010)18 | 31 | 63 (22–80) | – | Lenalidomide was given orally at escalating doses of 25–75 mg daily on days 1 through 21 of 28-day cycles. | – | Relapsed/refractory AML | – | |

| Fehniger et al (2011)19 | 33 | 71 (60–88) | 36% | Lenalidomide (50 mg/day in a single daily dose) on days 1–28 of a 28-day cycle for up to two cycles, followed by lenalidomide 10 mg/day in 28-day cycles up to 12 cycles. | 53 (21–97) | None | Untreated AML | Median 4 months (95% CI, 3–9 months) |

| Griffiths et al (2016)30 | 45 | 64 (33–82) | 44% | Cytarabine arabinoside 1.5 g/m2/day over 3 hours on days 1–5 with initiation of daily. Lenalidomide (25–50 mg/day) on days 6–26 of a 28-day cycle. | – | Chemotherapy None | Relapsed/refractory AML Untreated AML | Median (95% CI) was 5.8 (2.5, 10.6) months |

| Medeiros et al (2018)20 | 54 | 76 (66–87) | 40% | Lenalidomide (50 mg/day) on days 1–28 day for first two cycles, lenalidomide (25 mg/day) on days 1–28 day next two cycles, lenalidomide (10 mg/day) on days 1–28–day continuous cycles; azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 daily for days 1–7, followed by lenalidomide 50 mg daily for days 8–28. | 56 (22–95); 37 (12–84) |

1--year survival rates was 21% with lenalidomide, and 44% with sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide | ||

| Narayan et al (2016)25 | 26 | 73.5 (61–86) | 44% | Azacitidine at 75 mg/m2 daily for days 1–7, followed by lenalidomide 50 mg daily for days 8–28, with a cycle length of 42 days, up to six cycles | 32 (9–92) | HMAs, immunomodulatory therapy | Previously-treated AML | Median 5 months (95% CI, 3.7–8.6; range, 0.5–28.6 months) |

| Pollyea et al (2012)26 | 18 | 72 (62–86) | 33% | Azacitidine 75 mg/m2/day for 7 days followed by escalating doses (5 mg, 10 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg) of lenalidomide for 21 days starting on day 8 of each cycle. This was followed by 14 days of observation, for a total 42-day cycle, up to 12 cycles. | 64 (21–91) | None | Untreated AML | Median 8.2 months (range 0.7–16.0 months) |

| Pollyea et al (2013)27 | 45 | 74 (62–86) | 34% | Azacitidine 75 mg/m2/day for 7 days followed by escalating doses (5 mg, 10 mg, 25 mg and 50 mg) of lenalidomide for 21 days starting on day 8 of each cycle. This was followed by 14 days of observation, for a total 42-day cycle, up to 12 cycles. | 50 (20–91) | None | Untreated AML | Median 20 weeks (range, 1–121+ weeks) |

| Ramsingh et al (2013)28 | 19 | 72 (63–81) | 53% | Two 28-day induction cycles with lenalidomide 50 mg for days 1–28 and azacitidine given for days 1–5 at three-dose cohorts (25 mg/m2, 50 mg/m2 and 75 mg/m2); maintenance cycles with lenalidomide 10 mg for days 1–28 and azacitidine 75 mg/m2 for days 1–5, up to 12 cycles. | 23 (2–81) | Chemotherapy | Untreated AML/relapsed/ refractory | – |

| Sekeres et al (2011)29 | 37 | 74 (60–94) | 57% | Lenalidomide 50 mg daily for up to 28 days as induction therapy, maintenance lenalidomide at a dose of 10 mg daily for 21 days of a 28-day cycle, until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. | 38 (17–90) | None | Untreated AML | Median 2 months |

| Visani et al (2014)31 | 33 | 76 (70–85) | – | Lenalidomide (10 mg) was administered orally once daily (days 1–21); cytarabine (20 mg/m2 twice daily) was administered subcutaneously (days 1–15), up to six cycles. | – | None | Untreated AML | – |

| Visani et al (2017)32 | 66 | 76 (70–85) | 44% | Lenalidomide (10 mg) administered orally once daily (days 1–21) and cytarabine (10 mg/m2) administered subcutaneously twice daily (days 1–15), up to six cycles. | 60 (20–95) | None | Untreated AML | – |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; HMA, hypomethylating agent.

Though only one of the studies included in our meta-analysis was a randomized controlled trial, the “gold standard” trial design for clinical investigations, the included studies of our meta-analysis were selected on the basis of rigorous criteria to ensure a robust analysis of the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide in AML. Study quality scoring is shown in Table S1.

Funnel plots did not reveal any substantial publication bias in terms of the main outcomes of this meta-analysis.

Efficacy

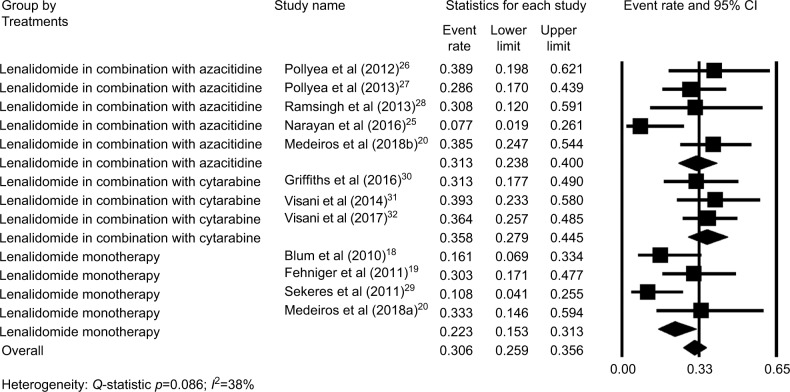

The ORR of eleven studies18–20,25–32 were moderately heterogeneous (P=0.086, I2=38%). Thus, the fixed-effect model was chosen for subsequent meta-analysis. The pooled estimate for the overall ORR was 31% (95% CI: 26%–36%; Figure 2). Subgroup analysis revealed that AML patients treated with lenalidomide monotherapy had a relatively low ORR (22%, 95% CI: 15%–31%), while patients treated with lenalidomide combinations had a higher ORR. The ORR for patients who were treated with lenalidomide in combination with azacitidine was 31% (95% CI: 24%–40%), and the ORR for patients who were treated with lenalidomide in combination with cytarabine was 36% (95%: CI 28%–45%; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the estimated proportions (95% CI) for overall response rate (ORR) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients treated with lenalidomide.

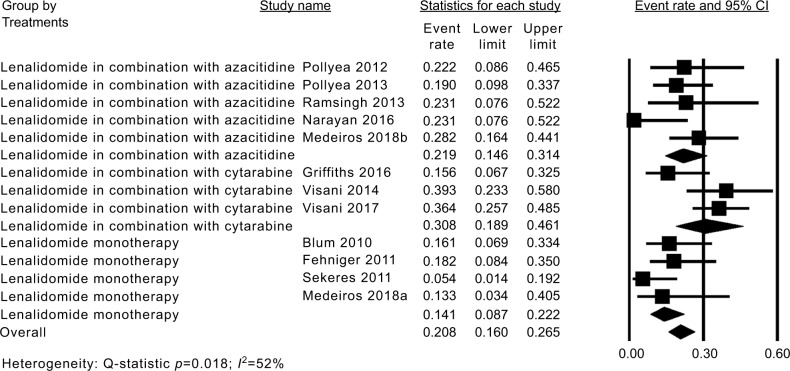

The CR of eleven studies18–20,25–32 was moderately heterogeneous (P=0.018, I2=52%). Thus, the fixed-effect model was chosen for subsequent meta-analysis. The pooled estimate for the overall CR was 21% (95% CI: 16%–27%; Figure 3). Subgroup analysis revealed that AML patients treated with lenalidomide monotherapy had a relatively low CR of 14% (95% CI: 9%–22%), while patients treated with a combination of lenalidomide and azacitidine and lenalidomide and cytarabine had higher CRs of 22% (95% CI: 15%–31%) and 31% (95% CI: 19%–46%; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the estimated proportions (95% CI) for complete remission (CR) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients treated with lenalidomide.

The OS of AML patients treated with lenalidomide was reported in six articles; in these articles, the median OS ranged from 2 to 8.2 months (Table 1).

Safety

Relevant safety data for lenalidomide were presented in ten articles and included the type, severity, and incidence of grade 3 and 4 AEs. Myelosuppression was the most common toxicity observed in patients treated with lenalidomide. The reported treatment risk-related AEs are shown in Figures S1 and S2: thrombocytopenia 56% (95% CI: 46%–66%), neutropenia 40% (95% CI: 33%–48%), anemia 34% (95% CI: 27%–42%), fatigue 19% (95% CI: 14%–25%), and electrolyte disturbance 18% (95% CI: 13%–25%). Infections and neutropenic fever were the most frequent complications, affecting 29% of cases (95% CI 23%–36%) and 35% of cases (95% CI 30%–41%), respectively.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis of AML type showed that the untreated AML patients had a relatively high ORR (33%, 95% CI: 28%–39%; Figure S3), while the ORR of relapsed/refractory AML patients was 21% (95% CI: 14%–32%), but the ORR of relapsed/refractory AML patients was 31% (95% CI: 18%–49%) for the combination of lenalidomide and cytarabine.

Sub-analysis of cytogenetic risk showed that the ORR of intermediate-risk was 29% (95% CI: 19%–41%; Figure S4) and that of unfavorable risk was 21% (95% CI: 13%–31%), suggesting that lenalidomide had slightly higher effects in the intermediate-risk patients. Unfortunately, a lack of data prevented us from evaluating favorable risk.

Randomized study of lenalidomide for AML treatment

Only one of the studies included in this meta-analysis was a randomized controlled trial.20 This particular study examined the effects of lenalidomide, sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide, or azacitidine only in individuals >65 years with newly diagnosed AML. Eighty-eight patients were randomized to one of the following groups: continuous high-dose lenalidomide (n=15), sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide (n=39), or azacitidine only (n=34). Patients who received continuous high-dose lenalidomide or sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide showed remissions similar to those who received the conventional dose and schedule of azacitidine, based on CR and CRi. Patients receiving continuous high-dose lenalidomide, or sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide did not show any improvement in 1-year survival when compared to those receiving azacitidine alone. At a continuous high-dose schedule, lenalidomide was poorly tolerated, with a high rate of patients opting to discontinue their treatment at a point early in therapy. Consequently, these data do not favor the use of continuous high-dose lenalidomide, or sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide, over the conventional dose and schedule of azacitidine in patients >65 years of age with newly diagnosed AML.

Discussion

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent that exhibits clinical activity against several myeloid malignancies including AML. This agent has been approved in the US and several other countries for the treatment of low-risk (low/intermediate-1) MDS patients with a deletion 5q abnormality. Even though there is a high prevalence of AML at present, there is still a paucity of randomized controlled trials examining the effect of lenalidomide in the treatment of AML. None of the trials investigated featured a placebo-control and most of the studies included in our meta-analysis were small open- label trials. The only randomized controlled trial we identified assessed the use of lenalidomide for newly diagnosed AML, and was not a placebo-controlled trial. Thus, the evidence in support of lenalidomide improving response rate in AML remains controversial, leaving clinicians with little information to use as a guide for the treatment of AML with lenalidomide. However, our present study may provide some evidence for the effect of lenalidomide as a single agent, or in combinations with other agents, as a form of treatment for AML.

The response rate of approximately 30% observed in our study was not dissimilar to previous response rates of patients undergoing regimens with either cytarabine or azacitidine alone.7,33 A previous pre-clinical study found that lenalidomide may enhance translation of the C/EBPα-p30 isoform, resulting in higher levels of miR-181a;34 higher expression levels of miR-181a is associated with an increased sensitivity to apoptosis-inducing chemotherapy in AML patients.34 Thus, higher levels of miR-181a expression are associated with a favorable response to treatment and better outcomes.35–37 However, our present study found that a combination of lenalidomide with cytarabine- or azacitidine-based regimens may have exacerbated the toxicity of their combination without capitalizing on the potential for synergy. The only published randomized controlled trial in this particular area also found that lenalidomide sequential azacitidine did not improve remission or 1-year survival compared to treatment with azacitidine alone. Recently, Visani et al published two studies that identified a response-predictive gene expression signature;31,32 these authors found that targeted global gene expression profile (GEP) can be regarded as a useful pre-treatment assessment to identify patients more likely to achieve a CR and a prolonged survival.33 More studies are therefore required in the future; these should evaluate the use of pre-treatment GEP to identify which population of AML patients is most likely to achieve remission with lenalidomide.

Cytogenetic risk is an important prognostic impact factor for AML patients. Our meta-analysis found that one-third of intermediate-risk and unfavorable-risk patients with AML responded to lenalidomide in combination with azacitidine. Furthermore, 31% of relapsed/refractory patients with AML responded to lenalidomide in combination with cytarabine. In fact, genomic abnormalities are likely to be the fundamental determinants of response to chemotherapy and survival in AML.38,39 However, following the combination of lenalidomide plus cytarabine or azacitidine, the cytogenetic risk and relapsed/refractory were shown to exert only minimal impact on the outcomes of our study. At present, we do not understand the mechanism of how lenalidomide acts in unfavorable-risk patients and relapsed/refractory patients with AML. Thus, this result of our study raises the question of whether pre-treatment molecular testing may provide the key to identifying specific patients most likely to respond to lenalidomide.

There are several limitations to this meta-analysis. Firstly, despite similar inclusion criteria and clinical assessments, some heterogeneity in the results was observed. Secondly, the sample size and number of studies used in the subgroup analysis were relatively small. Thirdly, the effects of OS, lenalidomide treatment regimens, and treatment response interactions were not explored, because there was an insufficient amount of data available. Finally, only published studies were included, which limited the amount of data available for our meta-analysis. Results from current unpublished studies may have an impact on these findings and should therefore be considered in the future. Despite these limitations, however, this paper reports a comprehensive meta-analysis that assesses the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide for the treatment of AML patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our meta-analysis found that one-third of the AML patients responded to lenalidomide treatments, and the cytogenetic risk and relapsed/refractory were shown to exert only minimal impact on the outcomes of lenalidomide treatments. Thus, lenalidomide may have some clinical activity in AML, but the population that would benefit from lenalidomide and incorporating lenalidomide into combination drug strategies need to be better defined. Several other factors may potentially undermine the validity of these findings, such as the limited number of studies, small sample size, and dose variability. There is an urgent need for more high-quality research evaluating lenalidomide monotherapy or lenalidomide in combination with other agents for the treatment of specific AML patients.

Supplementary materials

Forest plots of the estimated proportions of grade 3 and 4 adverse events ([A] anemia, [B] thrombocytopenia, [C] neutropenia, and [D] neutropenic fever).

Forest plots of the estimated proportions of grade 3 and 4 adverse events ([A] infectious, [B] fatigue, and [C] electrolyte disturbance).

Forest plots of subgroup analysis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) type ([A] untreated patients, [B] relapsed/refractory patients).

Forest plots of subgroup analysis of cytogenetic risk ([A] intermediate-risk patients, [B] unfavorable-risk patients).

Table S1.

Assessment of study quality using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies

| Study population clearly defined and >95% AML | Patients consecutively enrolled in the study | Cohort included AML patients diagnosed according to WHO criteria | Assessment of outcome well performeda | Primary and secondary outcomes defined | Adverse events defined | Adequate follow up of cohorts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blum et al (2010)1 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? |

| Fehniger et al (2011)2 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Griffiths et al (2016)3 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Medeiros et al (2018)4 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Narayan et al (2016)5 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Pollyea et al (2012)6 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ✮ |

| Pollyea et al (2013)7 | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? |

| Ramsingh et al (2013)8 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? |

| Sekeres et al (2011)9 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ? | ? |

| Visani et al (2017)11 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

Note:

Independent blind assessment, reference to secure records or record linkage.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ✮, yes; ?, no description.

References

- 1.Blum W, Klisovic RB, Becker H, et al. Dose escalation of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory acute leukemias. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(33):4919–4925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehniger TA, Uy GL, Trinkaus K, et al. A phase 2 study of high-dose lenalidomide as initial therapy for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(6):1828–1833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-297143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffths EA, Brady WE, Tan W, et al. A phase I study of intermediate dose cytarabine in combination with lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2016;43:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medeiros BC, Mccaul K, Kambhampati S, et al. Randomized study of continuous high-dose lenalidomide, sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide, or azacitidine in persons 65 years and over with newly-diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2018;103(1):101–106. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.172353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narayan R, Garcia JS, Percival ME, et al. Sequential azacitidine plus lenalidomide in previously treated elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia and higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(3):609–615. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1091930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollyea DA, Kohrt HE, Gallegos L, et al. Safety, effcacy and biological predictors of response to sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(5):893–901. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollyea DA, Zehnder J, Coutre S, et al. Sequential azacitidine plus lenalidomide combination for elderly patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98(4):591–596. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.076414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsingh G, Westervelt P, Cashen AF, et al. A phase 1 study of concomitant high-dose lenalidomide and 5-azacitidine induction in the treatment of AML. Leukemia. 2013;27(3):725–728. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekeres MA, Gundacker H, Lancet J, et al. A phase 2 study of lenalidomide monotherapy in patients with deletion 5q acute myeloid leukemia: Southwest Oncology Group Study S0605. Blood. 2011;118(3):523–528. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Visani G, Ferrara F, di Raimondo F, et al. Low-dose lenalidomide plus cytarabine induce complete remission that can be predicted by genetic profling in elderly acute myeloid leukemia patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(4):967–970. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visani G, Ferrara F, di Raimondo F, et al. Low-dose lenalidomide plus cytarabine in very elderly, unfit acute myeloid leukemia patients: Final result of a phase II study. Leuk Res. 2017;62:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Charlesworth Group (https://cwauthors.com/) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All the authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leopold LH, Willemze R. The treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse: a comprehensive review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(9):1715–1727. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000006529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löwenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(14):1051–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909303411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone RM. The difficult problem of acute myeloid leukemia in the older adult. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):363–371. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [Accessed December 29, 2017]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/amyl.html.

- 6.Klepin HD. Elderly acute myeloid leukemia: assessing risk. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10(2):118–125. doi: 10.1007/s11899-015-0257-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett A, Wetzler M, Löwenberg B. Therapeutic advances in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):487–494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta V, Tallman MS, Weisdorf DJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adults with acute myeloid leukemia: myths, controversies, and unknowns. Blood. 2011;117(8):2307–2318. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-265603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koreth J, Schlenk R, Kopecky KJ, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2349–2361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basara N, Schulze A, Wedding U, et al. Early related or unrelated haematopoietic cell transplantation results in higher overall survival and leukaemia-free survival compared with conventional chemotherapy in high-risk acute myeloid leukaemia patients in first complete remission. Leukemia. 2009;23(4):635–640. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta V, Tallman MS, He W, et al. Comparable survival after HLA-well- matched unrelated or matched sibling donor transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission with unfavorable cytogenetics at diagnosis. Blood. 2010;116(11):1839–1848. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dombret H, Raffoux E, Gardin C. New insights in the management of elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21(6):589–593. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283313e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1136–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estey E. Acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in older patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1908–1915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European Leukemia Net. Blood. 2010;115:453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang K, Earle CC, Foster T, et al. Trends in the treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(11):943–955. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Borthakur G. Lenalidomide as a novel treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22(3):389–397. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.758712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blum W, Klisovic RB, Becker H, et al. Dose escalation of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory acute leukemias. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(33):4919–4925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehniger TA, Uy GL, Trinkaus K, et al. A phase 2 study of high-dose lenalidomide as initial therapy for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(6):1828–1833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-297143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medeiros BC, Mccaul K, Kambhampati S, et al. Randomized study of continuous high-dose lenalidomide, sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide, or azacitidine in persons 65 years and over with newly-diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2018;103(1):101–106. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.172353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. [Last accessed September 7, 2018]. Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org.

- 22.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108(2):419–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(24):4642–4649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta–analysis. [Accessed December 29, 2017]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.

- 25.Narayan R, Garcia JS, Percival ME, et al. Sequential azacitidine plus lenalidomide in previously treated elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia and higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(3):609–615. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1091930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollyea DA, Kohrt HE, Gallegos L, et al. Safety, efficacy and biological predictors of response to sequential azacitidine and lenalidomide for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(5):893–901. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollyea DA, Zehnder J, Coutre S, et al. Sequential azacitidine plus lenalidomide combination for elderly patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98(4):591–596. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.076414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsingh G, Westervelt P, Cashen AF, et al. A phase 1 study of concomitant high-dose lenalidomide and 5-azacitidine induction in the treatment of AML. Leukemia. 2013;27(3):725–728. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekeres MA, Gundacker H, Lancet J, et al. A phase 2 study of lenalidomide monotherapy in patients with deletion 5q acute myeloid leukemia: Southwest Oncology Group Study S0605. Blood. 2011;118(3):523–528. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffiths EA, Brady WE, Tan W, et al. A phase I study of intermediate dose cytarabine in combination with lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2016;43:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visani G, Ferrara F, di Raimondo F, et al. Low-dose lenalidomide plus cytarabine induce complete remission that can be predicted by genetic profiling in elderly acute myeloid leukemia patients. Leukemia. 2014;28(4):967–970. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visani G, Ferrara F, di Raimondo F, et al. Low-dose lenalidomide plus cytarabine in very elderly, unfit acute myeloid leukemia patients: Final result of a phase II study. Leuk Res. 2017;62:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dombret H, Seymour JF, Butrym A, et al. International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with 30% blasts. Blood. 2015;126(3):291–299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-621664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hickey CJ, Schwind S, Radomska HS, et al. Lenalidomide-mediated enhanced translation of C/EBPα-p30 protein up-regulates expression of the antileukemic microRNA-181a in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(1):159–169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-428573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcucci G, Radmacher MD, Maharry K, et al. MicroRNA expression in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1919–1928. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Z, Huang H, Li Y, et al. Up-regulation of a HOXA-PBX3 homeoboxgene signature following down-regulation of miR-181 is associated with adverse prognosis in patients with cytogenetically abnormal AML. Blood. 2012;119(10):2314–2324. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwind S, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, et al. Prognostic significance of expression of a single microRNA, miR-181a, in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(36):5257–5264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115(3):453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcucci G, Haferlach T, Döhner H. Molecular genetics of adult acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):475–486. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Forest plots of the estimated proportions of grade 3 and 4 adverse events ([A] anemia, [B] thrombocytopenia, [C] neutropenia, and [D] neutropenic fever).

Forest plots of the estimated proportions of grade 3 and 4 adverse events ([A] infectious, [B] fatigue, and [C] electrolyte disturbance).

Forest plots of subgroup analysis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) type ([A] untreated patients, [B] relapsed/refractory patients).

Forest plots of subgroup analysis of cytogenetic risk ([A] intermediate-risk patients, [B] unfavorable-risk patients).

Table S1.

Assessment of study quality using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies

| Study population clearly defined and >95% AML | Patients consecutively enrolled in the study | Cohort included AML patients diagnosed according to WHO criteria | Assessment of outcome well performeda | Primary and secondary outcomes defined | Adverse events defined | Adequate follow up of cohorts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blum et al (2010)1 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? |

| Fehniger et al (2011)2 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Griffiths et al (2016)3 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Medeiros et al (2018)4 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Narayan et al (2016)5 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

| Pollyea et al (2012)6 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ✮ |

| Pollyea et al (2013)7 | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? |

| Ramsingh et al (2013)8 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ✮ | ? |

| Sekeres et al (2011)9 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ? | ? | ? |

| Visani et al (2017)11 | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ | ✮ |

Note:

Independent blind assessment, reference to secure records or record linkage.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ✮, yes; ?, no description.