Abstract

Fast food consumption is linked to poor health, yet many older adults regularly consume fast food. Understanding factors contributing to fast food consumption is useful in the development of targeted interventions. The aim of this study was to characterize how fast food consumption relates to socio-demographic characteristics in a low-income sample of older adults.

This study used cross-sectional survey data of 50 to79-year-olds (N-236) in urban safety-net clinics in 2010 in Kansas City, KS. Self-reported frequency of fast food consumption was modeled using ordinal logistic regression with socio-demographics as predictor variables. Participants were 56.8 ± 6.0 (mean ± SD) years old, 64% female, 45% non-Hispanic African American, and 26% Hispanic. Thirty-nine percent denied eating fast food in the past week, 36% ate once, and 25% ate fast food at least twice. Age was negatively correlated with fast food intake (r = −0.20, P = 0.003). After adjusting for age, race-ethnicity, employment, and marital status, the association between education and fast food consumption differed by sex (Pinteraction = 0.017). Among women, higher education was associated with greater fast food intake (Spearman's correlation; r = 0.28, P = 0.0005); the association was not significant in men (r = −0.14, P = 0.21). In this diverse, low-income population, high educational attainment (college graduate or higher) related to greater fast food intake among women but not men. Exploration of the factors contributing to this difference could inform interventions to curb fast food consumption or encourage healthy fast food choices among low-income, older adults.

Keywords: Fast food, Older adults, Diet quality, Education, Socio-demographic characteristics

1. Introduction

Good nutrition is important for older adults (Bernstein and Munoz, 2012). Eating fast food makes it harder to maintain a healthy diet (Moore et al., 2009). Fast food intake is associated with greater body mass index (Bowman and Vinyard, 2004), adult weight gain (Pereira et al., 2005), the development of insulin resistance (Pereira et al., 2005), and increased mortality risk (Barrington and White, 2016); therefore, the rise of fast food consumption in the U.S. and around the world (Bowman and Vinyard, 2004) is a public health concern.

Previous research has identified major risk factors for eating fast food. Living near fast food outlets is associated with greater consumption (Moore et al., 2009). In a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, fast food consumption was associated with higher household income, African American racial-ethnic identity, and younger age (Bowman and Vinyard, 2004). Among high consumers, the most commonly cited reasons for eating fast food are convenience and taste (Rydell et al., 2008). However, in reports describing risk factors for fast food consumption (Bowman and Vinyard, 2004; French et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2009; Pereira et al., 2005; Rydell et al., 2008; Satia et al., 2004), there has been scant attention to how sex may influence associations with fast food consumption.

Women eat differently from men in part because women tend to believe that healthy eating is more important (Wardle et al., 2004). A qualitative study of older adults found that barriers to healthy eating differ for men and women; men struggle with taste preferences, convenience of fast food, and a lack of self-control, while women found the greatest difficulty in cooking healthy meals (Wu et al., 2009). Identifying sex differences in reasons for consuming fast food would be valuable for the development of targeted interventions.

Hence, we sought to characterize how fast food consumption relates to socio-demographic characteristics in a sample of low-income, older adults.

2. Materials and methods

The aim of this study was to characterize how fast food consumption relates to socio-demographic characteristics in a low-income sample of older adults. Electronic surveys were administered to 236 adults aged 50–79 years in safety-net clinics in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Self-reported frequency of fast food consumption was modeled using ordinal logistic regression with socio-demographics as predictor variables.

2.1. Recruitment

Participants were recruited from nine safety-net clinics in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Study staff screened participants for eligibility and obtained informed consent, which was approved by University of Kansas Medical Center's Institutional Review Board. Eligibility criteria included age ≥50 years, income ≤150% of the Federal Poverty Level, current home address and working phone, no family history of colorectal cancer <60 years, and not up to date with colorectal cancer screening. The participants of this study include the 236 individuals who were randomized to the Comparison group in a randomized controlled trial of a touchscreen intervention of “implementation intentions” (a stage-theory-framed model of health behavior change) with a primary outcome of colorectal cancer screening completion. The comparison group completed a health survey, including information about fast food intake, that was time-matched to the touchscreen intervention. More detail about the parent study is available elsewhere (Greiner et al., 2014).

2.2. Data collection and variable coding

Participants answered questions on a touchscreen computer in the waiting area of the safety net clinic before their scheduled appointment. The content was presented in English or Spanish.

Age was measured in years. Participants were classified by their self-reported, combined race and ethnicity as non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Other.

Employment status was consolidated into a categorical variable with three levels: employed (full-time and part-time), home by choice (homemaker and retired), and unemployed (unemployed, disability/unable to work, seasonal, and other).

Marital status was consolidated into a dichotomous variable (partner versus no partner), conveying whether the person had a romantic partner: married and living with partner were included in the partner variable while the no partner variable included those indicating divorced/separated, widowed, never married, and other.

Education was consolidated into four levels (less than high school completion, high school completion or GED, some college or technical school degree, and at least college graduate). Participants were also asked if they had health insurance.

Fast food consumption was measured with the following question: “During the past week, on how many times did you eat fast food from restaurants like McDonald's, Pizza Hut, KFC, Taco Bell, or from convenience stores like Casey's or Kwik Shop?” Participants could respond with “None,” “One,” “2–3,” or “4 or more.” Fast food consumption frequency was consolidated from four to three levels, because only seven participants (2.9%) reported frequenting a fast food outlet four or more times in the past week.

2.3. Statistical approach

Associations with the dependent variable, fast food intake, were analyzed using ordinal logistic regression modeling (Brant, 1990) using JMP version 13.0 (SAS Institute). Independent variables included age, race-ethnicity, employment, marital status, education, sex, and a two-way interaction term between sex and each of the independent variables. Using a threshold of P < 0.05 as statistically significant, each two-way interaction term was tested with inclusion of all other covariates. The strength of association between an independent variable and fast food consumption is conveyed by Spearman's correlation.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the dependence of significant findings on the chosen statistical approach. First, other covariates were removed to assess if adjustment for confounders was responsible for statistical significance. Next each consolidation scheme (employment, marital status, education level, and fast food intake) was tested by individually replacing the variable with its raw counterpart. Finally, fast food intake was modeled as a continuous variable using linear regression.

3. Results

Participants were 56.8 ± 6.0 (mean ± SD) years old. The mean age in years was 57.2 ± 6.5 for women and 56.2 ± 4.9 for men (mean ± SD). The age distribution was skewed toward the lower end of the eligible range. Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics. A majority reported membership to a racial-ethnic minority. Low educational attainment, high unemployment, and common lack of health insurance indicate the economic vulnerability of the study population. Men and women had significantly different distributions of employment status; however, men and women were comparable on all other reported measures.

Table 1.

Characteristics of male and female participants.

| Men (n = 85) |

Women (n = 151) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Pb | ||

| Race-ethnicity | Non-Hispanic AA | 38 | 45% | 70 | 46% | 0.81 |

| Hispanic | 20 | 24% | 41 | 27% | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 25 | 29% | 36 | 24% | ||

| Education | Non-Hispanic other <High school grad |

2 18 |

2% 21% |

4 52 |

3% 34% |

0.061 |

| High school/GED | 31 | 37% | 40 | 27% | ||

| College/Tech School | 21 | 25% | 43 | 29% | ||

| Employment | ≥College grad Employed |

15 21 |

18% 25% |

16 41 |

11% 27% |

0.0001a |

| Home by choice | 7 | 8% | 45 | 30% | ||

| Unemployed | 57 | 67% | 65 | 43% | ||

| Marital Status | No partner | 57 | 67% | 115 | 76% | |

| Partner | 28 | 33% | 36 | 24% | 0.13 | |

| Have health insurance? | Yes | 26 | 31% | 34 | 23% | 0.17 |

| How many times did you eat fast food in the past week? | None | 31 | 37% | 61 | 40% | 0.67 |

| Once | 30 | 35% | 55 | 36% | ||

| 2 or more | 24 | 28% | 35 | 23% | ||

GED, General Educational Development. AA, African American.

Denotes significance.

P-value assesses the difference in proportions between men and women calculated by Pearson's chi-squared test or the mean difference in age by Student's t-test. Kansas City, KS. 2010.

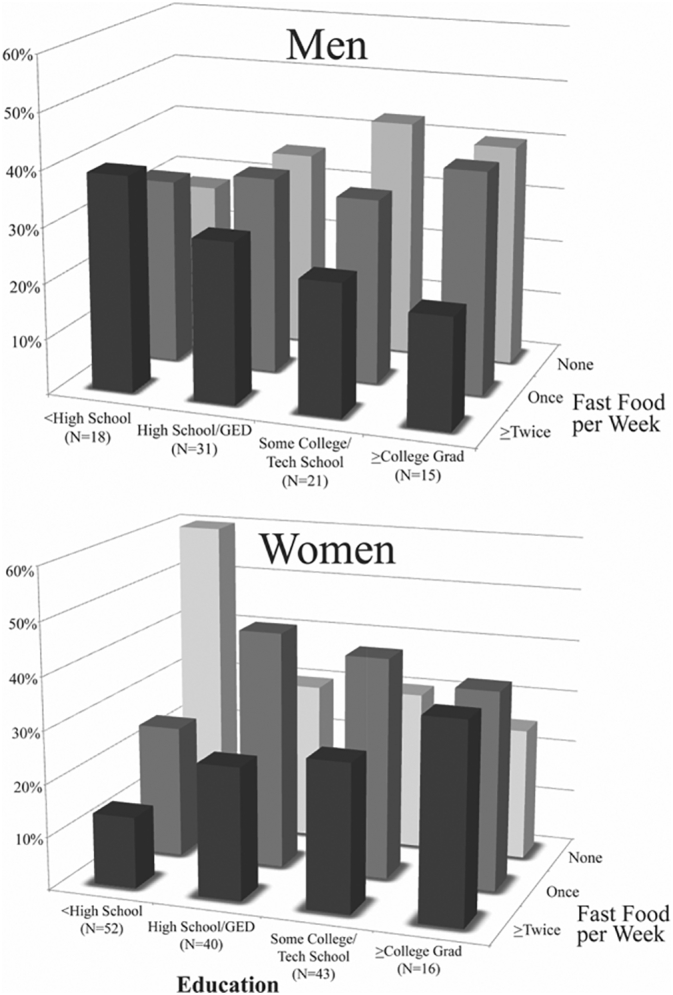

In the fully-adjusted model, the association between education and fast food consumption differed by sex (Pinteraction = 0.017); in this model, the only other significant predictor of fast food intake was age (P = 0.023). Among women, higher education was associated with greater fast food intake (Spearman's correlation; r = 0.28, P = 0.0005), while the association was not significant in men (r = −0.14, P = 0.21) (Fig. 1). Without inclusion of other covariates, age negatively correlated with fast food intake (r = −0.20, P = 0.003) (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Fast food consumption and education level by sex.

Association between education and fast food consumption differed significantly by sex (Pinteraction = 0.017 including covariates; age, race-ethnicity, employment status, and marital status). The percentage represents the proportion of those with that level of education who reported that level of fast food intake. Among women, higher education was associated with greater fast food intake (r = 0.28, P = 0.0005). Education was not associated with fast food intake among men (r = −0.14, P = 0.21). Kansas City, KS. 2010.

Sensitivity analyses showed that statistical significance of the two-way interaction was not contingent on inclusion of covariates (P = 0.0023) or variable consolidation schemes (all P < 0.05). Additionally, a similar result was obtained when modeling fast food intake as a continuous variable (P = 0.024). We performed one final analysis stratified by employment status out of theoretical concern that this variable was confounding our main observation; this revealed that the interaction term between education and sex was strongest among those employed (P = 0.0035) and absent among those home by choice (P = 0.64) and unemployed (P = 0.37).

4. Discussion

This is the first report of a significant interaction between sex, education, and fast food consumption. Higher education was correlated with greater frequency of fast food intake among women, but not men. The interaction was statistically independent of important covariates. Stratified analysis showed that the interaction was chiefly coming from the older adults who were regularly working outside of the home. Also, in our sample of older adults, we corroborated the observation that younger people tend to eat fast food more frequently.

Reports of associations between education and fast food consumption provide inconsistent results in varied populations. Pereira et al. reported education was negatively associated with fast food intake among non-Hispanic white people and observed an overall trend of decreasing fast food intake among white people during the 15 year prospective study (Pereira et al., 2005). Another study reported that, among working Americans who purchase their lunch, those younger and less educated were significantly more likely to choose fast food (Blanck et al., 2009). However, a representative sample of adults aged 18–64 years in Michigan revealed no association between fast food consumption frequency and education (Anderson et al., 2011). In younger, non-Hispanic African American populations, no evidence has been reported of an association between education and fast food consumption frequency (Pereira et al., 2005; Satia et al., 2004). Likewise, education was not associated with fast food consumption in a sample of younger women (20–45 years) (French et al., 2000). Existing literature illustrates how the relationship between education and fast food consumption is nuanced; it is moderated by sex, race-ethnicity, and possibly age. Therefore, future research in this area of public health and nutrition should analyze after stratification.

Eating more fast food is associated with citing too little time for cooking (Rydell et al., 2008). As reviewed elsewhere, time scarcity is a major contributor to unhealthy food choices (Jabs and Devine, 2006). Employed Americans eat fast food more often than people who are not working (French et al., 2000). Notably, higher education correlates with a higher level of job involvement, including more complex work tasks and more responsibility (Griep et al., 2016; Schieman et al., 2006). In the United States, women are more likely than men to spend time outside of paid work on food preparation and housework (Statistics, B.o.L., 2016). Women are also more likely than men to be primary caretakers of both children and aging parents (Bureau, 2016; Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002). Consequently, work-family conflict and stress associated with work-family conflict correlate with increased job involvement for women but not for men (Falkenberg et al., 2017). Differences between men and women in total workload (paid work and family/household responsibilities) may put women at disproportionate risk for work-family conflict, time-scarcity, and associated health hazards. Having too little time to prepare healthy food may be an important contributor to poor dietary choices among older, well-educated women.

The positive association we have identified here between fast food consumption and female education, especially among those employed, could reflect that highly educated women have higher work involvement than less educated women in addition to being more responsible for dependent care, housework, and food preparation for themselves and their households, compared to their male counterparts. Indeed, one qualitative study analyzing differences in healthy behaviors between older men and women states “men said that their wives were responsible for healthy diets” (Wu et al., 2009).

Although the nutritional dangers of fast food must be emphasized, there is some evidence that visiting fast food restaurants can be beneficial. For instance, some older adults frequent fast-food outlets for positive social activity (Cheang, 2002). Also, some fast food options can be classified as healthy food choices.

The results of this study are subject to the limitations of our data. We did not collect data on the number of children or other dependents in the household, and we do not know what degree of caretaking responsibility any of the participants had. We also do not know what participants chose to eat when they ate fast food or what their portion sizes were. Finally, our study population comprises only older adults. Further research is needed to determine whether a positive association between fast food consumption and female education is present in a younger study population.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that the association between fast food intake and education depends on sex. Higher education in our sample population is correlated with greater fast food intake among women, but not men. Furthermore, the interaction term between education and sex was strongest among those employed. Understanding how socio-demographic characteristics relate to fast food intake will help inform practical solutions to this important public health problem.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center's Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA123245) (PI: Greiner), and the University of Kansas Clinical Translational Science Program (Frontiers, from the National Cancer Institute at NIH) (PI: Greiner). Funders listed had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Authors' contributions

BH contributed toward design, statistical analysis, and writing; CH, CD and KG contributed to design, analysis, and writing; and KB contributed to analysis, and writing.

Acknowledgments

A strong partnership with the Wyandotte Country Kansas Safety Net Clinic Coalition was critical for the success of this study. The authors would like to thank study staff in the Family Medicine Research Division, particularly Angela Watson, M.B.A., Marina Carrizosa-Ramos, Heraclio Perez, Megan Eckles, M.P.H., Andrew Witt, Kris Neuhaus, M.D., M.P.H., Crystal Lumpkins, Ph.D. and Aaron Epp, for help with recruitment, survey administration and data collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.09.005.

Contributor Information

Brandon H. Hidaka, Email: hidaka.b@ghc.org.

Christina M. Hester, Email: chester@aafp.org.

Kristina M. Bridges, Email: kbridges@kumc.edu.

Christine M. Daley, Email: cdaley@kumc.edu.

K. Allen Greiner, Email: agreiner@kumc.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary table

References

- Anderson B., Rafferty A.P., Lyon-Callo S., Fussman C., Imes G. Fast-food consumption and obesity among Michigan adults. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington W.E., White E. Mortality outcomes associated with intake of fast-food items and sugar-sweetened drinks among older adults in the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) study. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:3319–3326. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein M., Munoz N. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: food and nutrition for older adults: promoting health and wellness. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012;112:1255–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanck H.M., Yaroch A.L., Atienza A.A., Yi S.L., Zhang J., Mâsse L.C. Factors influencing lunchtime food choices among working Americans. Health Educ. Behav. 2009;36:289–301. doi: 10.1177/1090198107303308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman S.A., Vinyard B.T. Fast food consumption of US adults: impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004;23:163–168. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brant R. Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics. 1990:1171–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau U.S.C. 2016. Table FG10. Family Groups: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheang M. Older adults' frequent visits to a fast-food restaurant: nonobligatory social interaction and the significance of play in a “third place”. J. Aging Stud. 2002;16:303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg H., Lindfors P., Chandola T., Head J. Do gender and socioeconomic status matter when combining work and family: could control at work and at home help? Results from the Whitehall II study. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2017 ( http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0143831X16682307) [Google Scholar]

- French S.A., Harnack L., Jeffery R.W. Fast food restaurant use among women in the Pound of Prevention study: dietary, behavioral and demographic correlates. Int. J. Obes. 2000;24:1353. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner K.A., Daley C.M., Epp A. Implementation intentions and colorectal screening: a randomized trial in safety-net clinics. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014;47:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griep R.H., Toivanen S., van Diepen C. Work-family conflict and self-rated health: the role of gender and educational level. Baseline data from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;23:372–382. doi: 10.1007/s12529-015-9523-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J., Devine C.M. Time scarcity and food choices: an overview. Appetite. 2006;47:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L.V., Roux A.V.D., Nettleton J.A., Jacobs D.R., Franco M. Fast-food consumption, diet quality, and neighborhood exposure to fast food the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;170(1):29–36. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp090. (kwp090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaie-Waliser M., Feldman P.H., Gould D.A., Levine C., Kuerbis A.N., Donelan K. When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am. J. Public Health. 2002;92:409–413. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M.A., Kartashov A.I., Ebbeling C.B. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell S.A., Harnack L.J., Oakes J.M., Story M., Jeffery R.W., French S.A. Why eat at fast-food restaurants: reported reasons among frequent consumers. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008;108:2066–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satia J.A., Galanko J.A., Siega-Riz A.M. Eating at fast-food restaurants is associated with dietary intake, demographic, psychosocial and behavioural factors among African Americans in North Carolina. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:1089–1096. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S., Whitestone Y.K., Van Gundy K. The nature of work and the stress of higher status. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2006;47:242–257. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics, B.o.L. 2016. American Time Use Survey (ATUS) [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J., Haase A.M., Steptoe A., Nillapun M., Jonwutiwes K., Bellisie F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004;27:107–116. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Goins R.T., Laditka J.N., Ignatenko V., Goedereis E. Gender differences in views about cognitive health and healthy lifestyle behaviors among rural older adults. The Gerontologist. 2009;49:S72–S78. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table