Abstract

Introduction

College students frequently display references to substance use, including marijuana, on social media such as Facebook. The significance of displayed marijuana references on social media is unknown. The purpose of this longitudinal cohort study was to evaluate college students’ displayed marijuana references on Facebook and their association with self-reported marijuana use.

Methods

First-year students from two US universities were randomly selected from registrar lists for recruitment. Data collection included 4 years of monthly Facebook coding, and yearly phone interviews that each assessed lifetime and current marijuana use. We compared frequencies of displayed marijuana references on Facebook between marijuana users and non-users using 2-sample t-tests and Pearson’s chi-squared tests. Generalized linear models were used to evaluate the likelihood of displayed marijuana references on Facebook.

Results

A total of 338 participants were recruited, 56.1% were female, 74.8% were Caucasian, and 58.8% were from the Midwest college. Prevalence of displayed marijuana references on Facebook profiles varied from 5–10% across four years. Displayed marijuana references included most “Actions” and Locations” on the Facebook profile. Marijuana users were more likely to display marijuana references on Facebook compared to non-users, though Likes were more common among non-users. Predictors of displayed marijuana references included lifetime and current marijuana use.

Discussion

The prevalence of displayed marijuana references on Facebook was consistent but uncommon; marijuana references included both information sharing and personal experiences. Marijuana users were more likely to display marijuana references, suggesting these displays could be leveraged for intervention efforts.

INTRODUCTION

For the 66.2% of American youth that attend post-secondary education,[1] college often represents a time of increased exposure to[2] and experimentation with marijuana.[3] Marijuana use increases after high school for youth who attend 4-year colleges compared to youth who do not.[4] The American College Health Association data reports that approximately one-third of college students have tried marijuana[5] and it is second only to alcohol among substances most used by college students.[6] Marijuana use can take many trajectories over college, including early heavy use that may include daily smoking, or intermittent use in social contexts.[7, 8]

While common, marijuana is associated with numerous adverse consequences including increased academic difficulties and greater psychiatric impairment. [9–12] Increased frequency of marijuana use has been found to be associated with risky sexual behavior and higher alcohol consumption.[13] The American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement regarding marijuana argued that given the evidence regarding negative health and brain developmental effects of marijuana in youth up to age 21 years, “the AAP is opposed to marijuana use in this population.”[14] Given the prevalence of marijuana use and associated negative health consequences, research to improve identification and intervention for college students to prevent these consequences is an important public health priority.

One potential innovative approach to understanding and identifying collegiate marijuana use is via social media. College students are avid users, with upwards of 90% using one or more social media platforms.[15] Social media use can contribute to identity development and friendship formation during this critical developmental period.[16] Studies have suggested that marijuana content is commonly displayed on social media sites such as Twitter[17] and YouTube[18]. These previous studies have focused on describing marijuana displays on a particular social media platform, many of which are displayed by organizations promoting marijuana use or legalization. A current gap in the literature is understanding displayed marijuana references by individuals who choose to integrate marijuana content into their online identity. If displayed marijuana references on social media are associated with marijuana use, then opportunities may exist for peers, peer-leaders such as dormitory resident advisors[19], or other adult role models to provide timely and targeted screening, education or prevention messages. These messages may even be deliverable via social media. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate college students’ displayed marijuana reference on Facebook.

This longitudinal cohort study followed Facebook profiles of college students for four years. Based on previous studies of displayed alcohol references and self-reported alcohol use[20], we hypothesized there would be a positive association between displayed marijuana references and self-reported use. We further tested this association across different frequencies of marijuana use. Our second hypothesis was that different Facebook actions or profile locations may vary in their association with self-reported marijuana use. Previous studies have found a stronger association between posts on certain locations and self-report for Facebook alcohol displays.[21] Thus, we evaluated the relationship between characteristics of displayed marijuana references on Facebook, including Location and Action on Facebook, and self-reported marijuana use.

METHODS

Study design and Setting

This longitudinal cohort study recruited incoming college students in 2011, data collection included Facebook evaluation and phone interviews yearly through 2015. The study included two state universities, one in the Northwest and one in the Midwest. Data for this study was collected between May 15, 2011 and September 23, 2015. This study received approval from the two relevant Institutional Review Boards.

Subjects

Incoming students from the two study universities were recruited prior to starting college. We randomly selected potential participants from the registrar’s lists at both universities. Participants were eligible if they were between the ages of 17 and 19 years, English speaking, owned a Facebook profile and had enrolled as a full-time first-year student at a study-related university. Based on our previous studies of associations between social media display and self-report, our target recruitment was 300 participants.

Recruitment

Recruitment involved several steps beginning with a pre-announcement postcard. Over a one-month recruitment period, potentially eligible students were recruited through emails, phone calls and Facebook messages. Eligibility criteria was assessed and informed consent was completed by phone for all enrolled participants.

Consent process and Facebook “friending”

During the consent process potential participants were informed that this was a 4-year study involving yearly phone interviews and Facebook “friending” a research team profile. When two Facebook profiles are “friended,” profile content becomes mutually accessible. Participants were informed that their Facebook profile content would be viewed, but that no screenshots would be taken, and no content would be posted on the participant’s profile by the research team. Participants were asked to maintain open security settings with the research team’s Facebook profile.

Facebook coding

Coder training to identify displayed Facebook marijuana references

The coder training period began with a trainee reviewing an established coding manual[22] and observing trainers. Trainee coders then progressed to supervised preliminary coding. In this stage, trainee coders practiced with training datasets and coded data was reviewed and discussed with trainers. Once competency was achieved through evaluation of interrater agreement with trainers on practice datasets, coders began assessing study data. Initial coder training lasted approximately 6–8 weeks. For ongoing training, weekly meetings of all coders provided opportunities to review key coding rules and discuss difficult or unique cases.

Coding variables

Our primary coding variable was a displayed marijuana reference. Our standard approach was used to evaluate whether a displayed Facebook reference met criteria as representing marijuana, described in previous publications and studies.[22–24] A displayed marijuana reference was defined applying the Theory of Reasoned Action framework, which supports the importance of attitudes and intentions in predicting behaviors.[25–27] Accordingly, posts on Facebook that addressed attitudes, intentions or behaviors regarding marijuana were considered marijuana references, though coders did not categorize references as attitudes, intentions or behaviors during the coding process. Coders were trained to include alternative and slang terms for marijuana including weed, pot and cannabis, and resources to evaluate new or emergent terms for relevance. Example marijuana references included personal photographs in which the profile owner was smoking a substance labeled as “pot” in the picture caption, text references describing intending to consume weed at a party, or “Likes” including marijuana-related content. Only photographs that contained the profile owner with clearly recognizable or labeled marijuana were included; thus, ambiguous photos of smoking were not considered marijuana references. Only text references that explicitly mentioned the profile owner’s attitudes, intentions or behaviors towards marijuana were coded as marijuana references. Profiles with one or more marijuana references on Facebook in any coding period were categorized as “Marijuana Displayers.”

Each displayed marijuana reference was categorized by the type of Facebook “Action” it represented as well as the profile “Location.” Actions included profile changes or updates, examples included posting content such as a status update, Liking content, updating the “About” personal section of the profile or being tagged by someone else. Further, each marijuana display was categorized by profile Location, which was where on the profile the activity took place. Locations included the Likes section, Timeline, Tagged photos, Uploaded photos and About section.

To assess coder reliability over the 4 years of data collection, we conducted reliability assessments for a 3-month period each year which included approximately 10% of the collected data. We calculated interrater agreement given the number of marijuana displays present per year. Interrrater agreement ranged between 93% and 96% for the four years of coding.[28]

Coding procedure

The Baseline evaluation of each participant’s Facebook profile included content from a three-month period during the spring of the participants’ senior year of high school. Upon matriculation, Facebook profile content was evaluated monthly for each preceding period.

During each profile evaluation, coders systematically evaluated the Facebook profile and recorded data into a secure database. Facebook profile locations that were evaluated included: (1) the Facebook Timeline including wall posts and comments, (2) Likes section which included businesses and groups the participant had “liked” on their profile, (3) photographs including a) the profile owner’s uploaded photos such as photo albums, profile pictures and cover photos, and b) tagged photographs which are photographs that have been labeled by the profile owner or an online friend with names of people in the picture. Extrapolated data included a typewritten description of images, verbatim text from profiles, and the date and time of the displayed marijuana reference. If marijuana references included names or other identifiable information, this information was not recorded.

Interview variables

Each interview included the same set of questions, including questions to assess participants’ marijuana use. Participants reported lifetime and current (past 28-day) use of any marijuana product. Lifetime use was defined as having ever used marijuana in their lifetime prior to the data collection time point. For participants who reported current marijuana use, we used the TimeLine Follow Back (TLFB) method to determine frequency in the last 28 days.[29] During this validated procedure the interviewer works with the participant to review each of the past 28 days to assess whether episodes of marijuana use took place.[30] This method was adapted from a validated alcohol assessment and has been used previously to assess marijuana.[30]

Demographics

We assessed demographic characteristics including gender, race/ethnicity and university at the Baseline interview.

Interview procedure

Baseline interviews were conducted with all participants before arriving at college. Interviews then took place once yearly for 4 years between 2012–2015. A total of 5 yearly interviews were conducted. Interviews were conducted by phone and lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. Trained research assistants conducted interviews and recorded data using a secure online database.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.1. All p values were 2-sided, and p < .05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

We defined frequent use of marijuana based on calculations using quantity responses from the TimeLine FollowBack Method. After calculating the quantity of marijuana use episodes over the 28-day period reported by participants, we determined the median number of episodes was 3. Thus, participants who reported 3 or more days of marijuana use were classified as frequent users. Those who ever reported using marijuana over the 75th percentile, calculated as 20 or more of the past 28 days, were classified as very frequent users.

We compared frequencies of Facebook display behaviors between marijuana use frequency groups and non-users using 2-sample t-tests (for continuous measures) and Pearson’s chi-squared tests (for binary measures). We used generalized linear models with a log link and a robust variance estimator to estimate relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the likelihood of displayed marijuana references on Facebook, associated with demographic as well as frequency of marijuana use (e.g. frequent, very frequent use). We estimated RRs in order to infer whether frequency of marijuana use was associated with a greater likelihood of displayed marijuana references on Facebook.

RESULTS

A total of 338 participants were recruited, of these 56.1% were female, 74.8% were Caucasian, and 58.8% were from the Midwest college, average age was 18.4 years (SD=0.6). Our recruitment response rate was 54.6%, and by the end of Year 4 our retention rate was 95.6%. Table 1 illustrates demographic characteristics of the participants in this study.

Table 1.

Participant information for college students from two US universities: Midwest and West

| n=338 | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Female | 190 (56.1%) |

| Male | 148 (43.9%) |

|

| |

| University | |

| Midwest | 199 (58.8%) |

| West | 139 (41.2%) |

|

| |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian/White | 253 (74.78%) |

| Asian | 39 (11.57%) |

| More than One | 21 (6.23%) |

| Hispanic | 13 (3.86%) |

| African American/Black | 5 (1.48%) |

| East Indian | 3 (0.89%) |

| Native American/Alaskan | 2 (0.59%) |

| Other | 2 (0.59%) |

Marijuana displays on social media

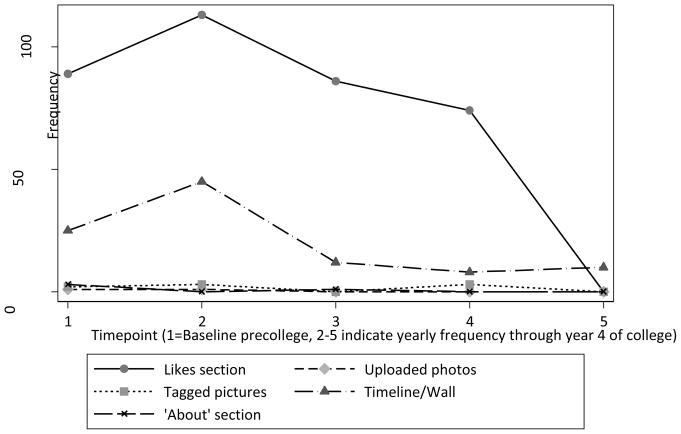

Across the four years of the study, displayed marijuana references on participant’s Facebook profiles ranged from a low of 4.8% pre-college, to a peak of 9.5% in year 1 of college (Table 2). Among the 338 participants, a total of 57 (16.8%) displayed marijuana references on Facebook one or more times across the 4 years of the study. Displayed marijuana references were present across all Actions and Locations on Facebook. Table 2 describes the frequency of marijuana displays and provides example Actions on Facebook that included displayed marijuana references. The most common Location for displayed marijuana references was the Likes section, Figure 1 shows the frequencies of marijuana displays by Location across the four years of college.

Table 2.

Frequency and examples of displayed marijuana references on Facebook among a prospective cohort of college students over four years

| Timepoint | N (%) of participants with one or more marijuana displays in that time period |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Pre-college | 16 (4.8%) |

| Year 1 | 32 (9.5%) |

| Year 2 | 30 (8.9%) |

| Year 3 | 16 (4.8%) |

| Year 4 | 19 (5.6%) |

|

| |

| Profile owner Action on Facebook | Examples |

|

| |

| Likes | NorML, Greenlink Collective |

|

| |

| Status update | “Well my parents know I smoke weed now” |

|

| |

| Photo with profile owner comment | “I was faded” |

|

| |

| Posted videos and links with profile owner comments | Friend posts video called “Marijuana, by Dope Smoker” and profile owner writes “saw this, and thought of you and your parents’ basement” |

|

| |

| Profile owner posts video or link with caption | Profile owner shared article entitled “New PMS Option: Cannabis Laced Vaginal Suppositories” with caption “Soooooooo this is a real thing and I want it.” |

Figure 1.

Frequency by year of college students’ displayed marijuana references by Location on the Facebook profile

Marijuana displays and self-reported use

Displayed marijuana references on Facebook were more frequent among participants who self-reported marijuana use. Approximately 22% of participants who reported lifetime marijuana use displayed references to marijuana on Facebook, while approximately 5% of participants who identified as marijuana non-users posted about marijuana on Facebook (p<0.001).

There were no significant differences by Action or Location in number of displayed marijuana references for participants who were marijuana users compared to non-users. However, we noted a trend that non-users were more likely to post in the Location of the “Likes” section (mean = 13.7 posts in “Likes,” SD=19.4) compared to marijuana users (mean = 5.7 posts in “Likes”, SD 11.0) (p = 0.11).

Among marijuana users, those who were categorized as frequent marijuana users were more likely to have posted marijuana displays on Facebook compared to those who were not frequent marijuana users (30% versus 18%, p=0.04). Among marijuana users, participants who were categorized as frequent marijuana users were more likely to display marijuana references using the Actions of Likes and Status Updates, compared to marijuana users who were not categorized as frequent marijuana users. Table 3 illustrates these data.

Table 3.

Displayed marijuana references on Facebook and participant self-reported marijuana use among a prospective cohort of college students over four years

| Self-reported marijuana use: None vs any lifetime use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No marijuana use (n=126) | Lifetime marijuana use (n=212) | p-valuea | |

| Among all participants (n=338), ever posted marijuana display on Facebook in the 4-year timeframe | 7 (5.6%) | 47 (22.2%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Among marijuana users: No history of frequent use versus any frequent use (≥3 days of past 28 days) | |||

|

| |||

| No frequent marijuana use (n=139) | Any frequent marijuana use (n=73) | p-valuec | |

|

| |||

| Among lifetime marijuana users (n=212), ever posted marijuana display on Facebook in 4-year timeframea | 25 (18.0%) | 22 (30.1%) | 0.043 |

| Number of marijuana displaysb | 3.5 (4.5) | 22.8 (34.6) | 0.013 |

| Facebook display Action Type: | |||

| Posted comments | 1.1 (2.2) | 2.0 (3.0) | 0.25 |

| Liked content | 1.7 (3.5) | 8.4 (12.1) | 0.011 |

| Photo uploaded | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.058 |

| Tagged photo | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.85 |

| Posted status updates | 0.4 (0.6) | 1.7 (2.6) | 0.017 |

| Content added to About | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.8 (1.5) | 0.065 |

| Comment by friend | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.29 |

| Facebook display Location:b | |||

| Likes section | 2.3 (5.3) | 9.5 (14.3) | 0.025 |

| Uploaded photos | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.13 |

| Tagged photos | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.83 |

| Timeline/wall | 1.0 (0.9) | 3.3 (4.9) | 0.023 |

| About section | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.18 |

p value represents Pearson’s chi-squared tests

Tallied each month; showing mean total per person and standard deviation

p value represents 2-sample t-tests

Predictors of displayed marijuana on Facebook

When assessing predictors of marijuana displays on Facebook, we found that demographic variables such as gender and race/ethnicity were not significant. Rather, the likelihood of displaying marijuana references on Facebook was strongly predicted by self-reported lifetime marijuana use prior to the display. Participants who displayed marijuana references on Facebook were almost 4 times as likely to self-report marijuana use by the end of college, after adjusting for a priori potential confounders of gender, race/ethnicity and university (RR = 3.9, 95% CI 1.8–8.4) Among marijuana users, those who had ever reported frequent use of marijuana were more likely to display marijuana references on Facebook (RR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.01–2.8) compared to users who did not report frequent use. Further, participants who had ever reported very frequent use of marijuana were more than twice as likely to display marijuana-related content (RR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.5–4.6) compared to marijuana users who did not report very frequent use. Table 4 illustrates these data.

Table 4.

Predictors of displayed marijuana references on Facebook among a prospective cohort of college students followed for four years

| Demographics | Unadjusted RR (95% CI)a | Adjusted RR (95% CI) b |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | - |

| Race/ethnicity | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | - |

| University | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | - |

|

| ||

| Marijuana use | ||

| Among all participants (n=338): | ||

| Lifetime use of marijuanac | 4.0 (1.9–8.6) | 3.9 (1.8–8.4) |

| Among lifetime users only (n=212): | ||

| Frequent use of marijuanad | 1.7 (1.02–2.8) | 1.7 (1.01–2.8) |

| Very frequent use of marijuanae | 2.5 (1.4–4.2) | 2.6 (1.5–4.6) |

Unadjusted relative risk and 95% confidence interval

Adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, university

Lifetime use defined as ever reported using marijuana; comparing ever vs non- users

Frequent use defined as ever reported use3 or more days in past 28 days; comparing frequent vs not frequent use

Very frequent use defined as ever reported using 20 or more days in past 28 days; comparing any very frequent vs no very frequent use

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal cohort study, we evaluated 4 years of displayed marijuana references on Facebook, and marijuana use by self-report. Findings included that marijuana displays were present throughout college but not common, and were more likely to be posted by marijuana users.

Our first finding was that marijuana displays occurred across all four years of college. Frequency of marijuana displays on Facebook was highest in the first year of college, rising from 5% of profiles pre-college to 10% in the first year of the study. These findings suggest that early college may represent a time for not just experimenting with new substances, but also displaying references to substance use to new friends via social media. Alternatively, the higher frequency of posts early in college may be a signaling effect of the pending legislation to legalize marijuana in 2012. Once legislation was passed, it is possible that students had less impetus to display posts supporting legalization. Display frequency dropped significantly at the end of college. As students neared graduation and considered job searching, it is possible that they were reluctant to have posts regarding marijuana on their Facebook profiles.

These findings further suggest that marijuana displays on Facebook are far less common compared to alcohol displays. Previous studies have reported that 50–80% of college students’ Facebook profiles include displayed alcohol references.[20, 23, 24, 31] There are several possible reasons for this lower frequency for marijuana displays. First, marijuana is still an illegal substance at the federal level, which may have contributed to lower frequency of posting by students. Second, during this study’s time period several other social media platforms were popular among college students, including Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat. It is possible that this type of content is more common on those platforms. Though the rates of marijuana display were low overall, our study demonstrates that marijuana displays were present across all types of Actions and Locations on the Facebook profile, with references including sharing of information and links in addition to sharing personal experiences with marijuana.

Though the types of marijuana posts on Facebook were varied, we found that marijuana references were more likely to be displayed by marijuana users compared to non-users. Thus, even if a displayed marijuana reference was not directly documenting personal use, the act of sharing marijuana information on social media was more likely to be undertaken by someone who had used marijuana. One possible exception was the higher frequency of posts in the “Likes” section among non-users than among lifetime marijuana users, “Likes” in particular often referred to marijuana advocacy groups. This trend may relate to the time period of this study, which included the 2012 legalization of marijuana for recreational use in Washington. The frequency of posted “Likes” were high early in the study, corresponding with the period in which recreational marijuana legalization was being actively debated in Washington State. The high frequency of Likes may reflect college students’ engagement in this social movement, or efforts to support this new policy even among non-users. Alternatively, this trend it may also reflect a desire among non-users to signal an acceptance toward marijuana use to new college friends.

Limitations of this study include the diversity of our sample. Though our sample is representative of the colleges from which the data was drawn, the sample is not representative of all colleges, especially those with more racially and ethnically diverse students. Further, our ascertainment of all interview variables, including substance use, was limited to self-report, creating the possibility for recall and social desirability bias. The TimeLine FollowBack method used in the research interviews is validated for helping to avoid the bias that comes with the passing of time since the event in question.[29] Participants were informed that we obtained a federal certificate of confidentiality for the study, which we hope helped participants feel comfortable accurately reporting behaviors related to drug use.

Despite these limitations, our study has important strengths and implications. A strength of the study is the longitudinal design. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study following individual social media users prospectively for a four-year period. Previous studies of college students have illustrated the importance of longitudinal studies to understand how behaviors do or do not change over time.[32]

A further strength is the focus on the individual and connecting online displays to offline behaviors. Previous studies have documented social media posts related to marijuana, particularly since legalization of recreational marijuana has grown across the US.[17, 18] Most studies of marijuana social media displays have focused on platforms such as Twitter and YouTube, in which content is often generated by businesses or promotional groups. This study fills a critical gap in understanding the prevalence and types of displayed marijuana references on Facebook by individuals over time, and the associations between displayed Facebook marijuana references and self-reported marijuana use.

Future studies may consider how to target marijuana education or intervention messages to these social media displays. For example, prevention-oriented message may be targeted to Likes as they are more likely to represent non-users of marijuana, while intervention or reduction messages may be targeted to other Actions or Locations in order to target those who are more at risk for engaging in marijuana use. Future studies can evaluate the acceptability of receiving targeted messages via social media, as well as testing these findings in other groups such as high school students or non-college attending young adults. As social media are likely to remain a staple in the lives of adolescents and young adults, researchers can investigate new ways to use these tools to better understand and reduce drug use.

Implications and contribution.

Previous studies have highlighted the presence of marijuana on social media; though the prevalence and meaning of individual college students’ displayed marijuana references remains unclear. This longitudinal cohort study found low prevalence of displayed marijuana on Facebook over four years, and positive associations between Facebook display and self-reported behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant R01DA031580-03 which is supported by the Common Fund, managed by the OD/Office of Strategic Coordination (OSC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Statistics, B.o.L. College Enrollment and Work Activity of 2012 High School Graduates. U.S. Department of Labor; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinchevsky GM, et al. Marijuana exposure opportunity and initiation during college: parent and peer influences. Prev Sci. 2012;13(1):43–54. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(5):1497–504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming CB, et al. Educational Paths and Substance Use From Adolescence Into Early Adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2012;42(2):104–126. doi: 10.1177/0022042612446590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association, A.C.H; M.A.C.H.A. Hanover, editor. American College Health Association - National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Fall 2011. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Primack BA, et al. Tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol use in university students: a cluster analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(5):374–86. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.663840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldeira KM, et al. Marijuana use trajectories during the post-college transition: health outcomes in young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(3):267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck KH, et al. The social context of cannabis use: relationship to cannabis use disorders and depressive symptoms among college students. Addict Behav. 2009;34(9):764–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zickler P. Marijuana Smoking Is Associated With a Spectrum Of Respiratory Disorders. National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. Available from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2006/10/marijuana-smoking-associated-spectrum-respiratory-disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gater P. Respiratory Effects of Marijuana. 2012 [cited 2012 July 19]; Available from: http://adai.uw.edu/marijuana/factsheets/respiratoryeffects.htm.

- 11.James A, James C, Thwaites T. The brain effects of cannabis in healthy adolescents and in adolescents with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2013;214(3):181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadwick B, Miller ML, Hurd YL. Cannabis Use during Adolescent Development: Susceptibility to Psychiatric Illness. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:129. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simons JS, Maisto SA, Wray TB. Addict Behav. Elsevier Ltd; England: 2010. Sexual risk taking among young adult dual alcohol and marijuana users; pp. 533–6. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pediatrics, A.A.o. The Impact of Marijuana Policies on Youth: Clinical, Research and Legal Update. AAP; Elk Grove Village, IL: 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duggan M, et al. Social Media Update 2014. Pew Internet and American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SS, et al. Face off: Implications of visual cues on initiating friendship on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 26(2):226–234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavazos-Rehg PA, et al. Twitter chatter about marijuana. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krauss MJ, et al. “It Takes Longer, but When It Hits You It Hits You!”: Videos About Marijuana Edibles on YouTube. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(6):709–716. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1253749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kacvinsky LE, Moreno MA. College Resident Advisor Involvement and Facebook Use: A Mixed Methods Approach. College Student Journal. 2014 In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno MA, et al. Associations between displayed alcohol references on facebook and problem drinking among college students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;166(2):157–63. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno MA, et al. Underage College Students’ Alcohol Displays on Facebook and Real-Time Alcohol Behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56(6):646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno MA, Egan KG, Brockman L. Development of a researcher codebook for use in evaluating social networking site profiles. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno MA, et al. A Content Analysis of Displayed Alcohol References on a Social Networking Web Site. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol References on Undergraduate Males’ Facebook Profiles. Am J Mens Health. 2011;413–420 doi: 10.1177/1557988310394341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fishbein M. A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; 1979; pp. 65–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montano DEKD. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In: Glanz KRB, Lewis F, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Reserach and Practice. John Wiley and Sons; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(23):2276–84. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobell L, Sobell M. TimeLine Follow-Back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson SM, et al. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for Cocaine, Cannabis, and Cigarette Use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Prevalence of Stress References on College Freshmen Facebook Profiles. Comput Inform Nurs. 2011 doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3182160663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arria AM, et al. Drug use patterns in young adulthood and post-college employement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]