Abstract

Influenza A H3N2 viruses circulate globally, leading to substantial morbidity and mortality. Commercially available, antigen-matched influenza vaccines must be updated frequently to match dynamic sequence variability in immune epitopes, especially within viral influenza A H3N2 hemagglutinin (H3). In an effort to create comprehensive immune responses against H3N2, four micro-consensus antigens were designed to mimic the sequence and antigenic diversity of H3. Synthetic plasmid DNA constructs were developed to express each micro-consensus immunogen and combined into a multi-antigen DNA vaccine cocktail, pH3HA. Facilitated delivery of pH3HA via intramuscular electroporation in mice induced comprehensive, potent humoral responses against diverse seasonal H3N2 viruses that circulated between 1968 and the present. Vaccination with pH3HA also induced an antigen-specific cellular cytokine response. Mice immunized with pH3HA were protected against lethal challenge using two distinct H3N2 viruses, highlighting the heterologous protection afforded by synthetic micro-consensus immunogens. These findings warrant further study of the DNA vaccine micro-consensus platform for broad protection against influenza viruses.

Keywords: : plasmid DNA vaccine, seasonal influenza

Introduction

Influenza viruses pose a substantial threat to global health and the world economy. Seasonal influenza infections lead to an estimated three to five million cases of severe disease and 290,000–640,000 deaths globally each year,1 despite widespread use of current vaccines and antiviral drugs. Influenza A and B viruses circulate seasonally. A subset of influenza viruses that emerged in humans in 1968, influenza A subtype H3N2, has led to substantial worldwide morbidity and mortality. The recent and markedly severe 2013/2014, 2014/2015, and 2017/2018 influenza seasons were attributed directly to H3N2 viruses.

Inactivated, live-attenuated, and recombinant influenza vaccines are currently available for prevention of seasonal influenza virus infection, morbidity, and mortality. However, these vaccine platforms have limited ability to induce broad immunity against diverse H3N2 viruses. Each vaccine is designed with only one rigorously selected seasonal H3N2 viral component combined with influenza A H1N1 and influenza B viral components. These vaccine formulations are revised annually at great effort and expense to counteract influenza virus antigenic drift and shift (viral reassortment). Furthermore, the vast majority of vaccine doses are produced via a time-consuming manufacturing process in eggs, meaning updates to viral components must be established months in advance of the influenza season.

The limited capacity of current vaccine design and manufacturing to meet the antigenic diversity of H3N2 viruses highlights a prescient need for a more comprehensive immunization strategy. Antigenic mismatch between vaccine components and circulating H3N2 viral strains results in poor vaccine efficacy. Mismatches are often attributable to amino acid mutations in influenza A H3N2 hemagglutinin (H3) antigenic site B, immediately adjacent to the viral receptor binding site.2 H3 antigenic drift led to reduced vaccine efficacy in the 2014/2015 season where commercial vaccines and circulating viruses carried discrepant H3 genetic clades 3C.1 versus 3C.2a/3C.3a, respectively.3,4 Another factor leading to antigenic mismatch is reassortment of H3N2 viruses.5 A dramatic H3N2 antigenic shift occurred in 2003/2004 with the emergence of A/Fujian/411/02-like viruses.6–8 Strikingly, current vaccine manufacturing techniques are yet another factor leading to compromised vaccine immunogenicity. Poor vaccine efficacy and elevated mortality rates in the most recent 2017/2018 season were attributed in part to a novel glycosylation motif in H3 site B that is not retained when viruses are passaged ex vivo.9,10

Here, a synthetic DNA vaccine was engineered to elicit broad immune responses against diverse influenza A H3N2 viruses. H3 sequences encompassing viruses from 1968 to the present were aligned to create four synthetic micro-consensus antigens. In vivo intramuscular electroporation (EP) of plasmid DNA expressing H3 antigens induced antigen-specific cellular cytokine responses with exceptionally broad, functional antibody responses against H3 in mice. Animals immunized with this synthetic DNA vaccine were protected against lethal influenza A infection from two different challenge H3N2 viruses. This synthetic DNA vaccine presents novel advantages for further study toward development of a comprehensive, safe, and scalable addition to current tools for prevention of severe seasonal influenza A H3N2 infection.

Methods

Phylogenetic analysis of influenza H3 amino acid sequences

Primary H3 protein sequences (n = 233) collected from H3N2 strains isolated over multiple decades were retrieved from the Influenza Research Database (IRD; www.fludb.org). Phylogenetic analysis was performed by multiple alignment with ClustalW using MEGA v7 software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on maximum likelihood evaluation of the alignment.

Design and construction of influenza DNA plasmid vaccine constructs

Four major clusters were determined by examining the H3 phylogenetic tree. Sequence analysis indicated that the H3 sequences comprising four major clusters differ between 2.5% and 6.5%. Thus, to minimize the sequence distance between the vaccine and influenza primary viruses and to maximize the potential of being able to elicit cross-protection against diverse strains in all clusters, four micro-consensus-based HA antigens (ConH3HA-1, ConH3HA-2, ConH3HA-3, and ConH3HA-4) were generated using 35, 101, 45, and 52 primary influenza H3 HA sequences located at each major cluster, respectively. Amino acid sequences for ConH3HA-1 through ConH3HA-4 were used to construct comparative models using Discovery Studio 2017 R2 (Biovia, San Diego, CA). The micro-consensus amino acid sequences were DNA codon/RNA optimized and de novo synthesized. ConH3HA-1 through ConH3HA-4 genes were each sub-cloned into a modified pVax-1 mammalian expression plasmid (pGX001) under the control of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter. The constructs were named as pH3-1, pH3-2, pH3-3, and pH3-4, respectively. Plasmid constructs pH3-1 through pH3-4 were co-mixed at 1:1:1:1 equimolar ratios in sterile DNAase-free water to form the cocktail vaccine, pH3HA.

Viral stocks and H3 antigens

Representative influenza viruses from all four micro-consensus regions were obtained from an influenza research reagent resource. A/Wisconsin/67/2005, A/Sydney/5/1997, A/Brisbane/10/2007, and reassortant A/Beijing/32/1992 (HA, NA) × A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H3N2 Reassortant X117) were collected in pooled allantoic fluid of pathogen-free embryonated chicken eggs (BEI Resources Repository, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA). Mouse-adapted challenge viruses A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 and A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31 (reassortant viruses carrying the HA and NA of these H3N2 strains and remaining viral RNA from H1N1 A/Puerto Rico/8/1934) were maintained by Bioqual, Inc. (Rockville, MD).

Recombinant influenza HA antigens with deleted transmembrane regions (HAΔTMp; A/Sydney/5/1997, A/Johannesburg/33/1994, A/Brisbane/10/2007, A/Wuhan/359/1995, A/Hong Kong/1/1968, A/Switzerland/9715293/2013, and A/Hong Kong/4801/2014) and HA1 (A/Wisconsin/67/X-161/2005) were isolated from transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cell culture at ≥90% purity (Immune Technology Corp., New York, NY). Peptides representing the full micro-consensus ConH3HA-1 HA sequence were synthesized as 15-mers with eight amino-acid overlap (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). Four linear peptide pools were formed by mixing equimolar peptides representing each quarter of the H3 protein sequence.

Western blot

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and transfected with consensus HA plasmid constructs pH3-1, pH3-2, pH3-3, pH3-4, or empty vector pGX001 using GeneJammer Transfection Reagent (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Cell lysates were collected and run on a NuPage 4–12% Bis-Tris protein gel with dry transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (iBlot 2; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Membrane was blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and stained with mouse anti-influenza-HA antibody and secondary antibody goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; H + L) IRDye 680RD (LI-COR Biosciences). Western blot was imaged using the Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Immunizations

Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were each immunized with 40 μg of total plasmid DNA (10 μg of each of the four micro-consensus constructs) formulated in 0.4 IU/mL of hyaluronidase (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA). DNA was delivered via a 30 μL injection to the tibialis anterior muscle, followed immediately by intramuscular EP with a CELLECTRA-3P device (Inovio Pharmaceuticals). The second (boosted) immunization was performed 2 weeks (14 days) later in the same manner at the same injection site. Control mice were immunized with 40 μg of empty pGX001 plasmid DNA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Ninety-six-well enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates (Nunc MaxiSorp; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 2 μg/mL of recombinant antigen overnight at 4°C, and blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; MilliporeSigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h at 25°C. Sera from individual mice were added at a 1:50 starting dilution, with fourfold serial dilutions in 0.5% BSA solution for 1 h at 25°C. Secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG-heavy-and-light-chain conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (MilliporeSigma) was added at 1:5,000 in 0.5% BSA for 1 h. Plates were developed for 20 min with SigmaFast o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) substrate (MilliporeSigma) and stopped with 2 M of sulfuric acid. Absorbance was read at a wavelength of 492 nm (Synergy 2; BioTek, Winooski, VT). Reciprocal endpoint binding titers were calculated according to the method described in Frey et al.11 at a 99% confidence level relative to control sera from five naïve untreated BALB/c mice.

Cellular responses

Spleens were harvested and individually placed in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS +100 IU/mL of penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Splenocytes were isolated by mechanical disruption using a Stomacher (Seward Laboratory Systems, Bohemia, NY) and filtration through a 40 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Red blood cells were lysed by treating for 5 min with ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (Lonza; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were washed in PBS and suspended in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS for use in enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) or flow cytometry assay.

Ninety-six-well ELISpot plates precoated with anti-mouse interferon gamma (IFN-γ) capture antibody (MabTech, Cincinnati, OH) were washed with PBS and blocked with RPMI medium. Splenocytes (2 × 105 cells/well) were plated in triplicate and stimulated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 with 1 μg/mL of H3 peptide pools in full RPMI. After 18–24 h of stimulation, the plates were developed as per the manufacturer's protocol, including sequential incubation with biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody and streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase. Spots were resolved by adding 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate and nitro-blue tetrazolium BCIP/NBT-plus substrate (MabTech) for 10–20 min. Plates were imaged using an automated ImmunoSpot reader (Cellular Technology Ltd., Cleveland, OH). Resolution, counting, and quality control were performed using ImmunoCapture v6.6 (Cell Technology Ltd.).

Splenocytes were added to a 96-well plate (1 × 106 cells/well) and stimulated for 5 h with peptide pools (1 μg/mL) or full RMPI medium alone (negative control). Stimulated cells were stained with a Zombie Yellow™ Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) followed by surface staining with anti-mouse CD4 (V450 conjugated, clone RM4-5; BD Biosciences), CD8 (PerCP-Cy 5.5, 53-6.7; BD Biosciences), CD44 (BV711, IM7; BioLegend), and CD62L (PE, MEL-14; BD Biosciences). Cells were washed three times in PBS +1% FBS, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and stained intracellularly with anti-mouse CD3ɛ (FITC, 145-2C11; BioLegend) and IFN-γ (AF700, XMG1.2; BioLegend). All cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and data were collected with a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software gating for live lymphocytes that are CD3+, CD4+ versus CD8+, CD44+ and CD62L−, and IFN-γ-producing relative to unstimulated (RPMI-treated) negative controls.

Hemagglutination inhibition and micro-neutralization assays

Fresh chicken red blood cells in Alsevers (Lampire Biological Products, Pipersville, PA) were washed three times in PBS and suspended in 0.8% sodium chloride saline solution. Lyophilized Receptor Destroying Enzyme (RDE) was reconstituted as per the manufacturer's recommendation (Denka Seiken Co. USA, Inc., San Jose, CA) and combined with individual mouse sera at a 3:1 volume ratio overnight at 37°C. RDE/sera were heat-inactivated 45 min at 56°C and pre-absorbed at a 1:1.1 volume ratio with 10% chicken red blood cells in saline at 4°C for 1 h. Chicken red blood cells were removed by centrifugation, yielding a final serum preparation. Influenza virus agglutination dose was determined by mixing 50 μL virus (undiluted and at a 1:10 dilution) with 50 μL of 0.5% chicken red blood cells in saline for 45 min at room temperature in 96-well V-bottom plates. For determination of serum hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titer, individual mouse sera were suspended at a final dilution of 1:20 in PBS and serially diluted twofold in a volume of 25 μL. Diluted sera were combined with four agglutinating doses (4 AD) of virus in 25 μL of PBS and incubated for 1 h at 25°C, followed by addition of 50 μL of 0.5% chicken red blood cells for 45 min. Each individual mouse serum sample HAI titer was assayed in triplicate.

Micro-neutralization assays and analysis were performed according to methods published by the World Health Organization (WHO).12 Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells (0.25 × 105; ATCC) were plated onto a flat 96-well plate overnight in complete DMEM with GlutaMAX, 50 μL/mL and 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sera samples were incubated with RDE at a 1:4 volume ratio overnight followed by heat inactivation. The next day, each serum sample was diluted 1:20 and serially diluted twofold in diluent DMEM with GlutaMAX and 50 μL/mL of gentamicin. Diluted sera were preincubated with 120 TCID50 of virus (titers were previously determined via serial dilutions of virus in MDCK cells) in a total volume of 120 μL of diluent at 37°C for 1 h. Complete media was removed from MDCK cells and replaced with 100 μL of media containing N-tosyl-L-phenylalanin chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) treated trypsin. Virus/sera pre-incubated mixture (100 μL) was added to each well of MDCK cells and incubated for 2 days at 37°C. Following incubation, infection was assayed by ELISA. Supernatant was replaced with cold fixative 80% acetone in PBS and plates were washed three times with PBS with 0.1% Tween20. Biotinylated antibody against influenza nucleoprotein (MAB 8258B-5; Millipore) was added for 1 h to plates at a dilution of 1:2,000 in blocking buffer PBS with 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween20. Plates were washed twice and blocked, followed by incubation with 1:10,000 horseradish peroxidase–conjugated streptavidin secondary antibody (ab6651; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) for 1 h. Plates were again washed and blocked, and developed with 100 μL of tetramethybenzidine (TMB) peroxidase substrate for 5–30 min and stopped with TMB stop solution (VWR International, Radnor, PA). Absorbance optical density values were determined at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Challenge studies

Six- to eight-week-old BALB/c mice (n = 10/group) were immunized with pH3HA (two doses) or placebo (pGX001 empty plasmid DNA). Two weeks following the final (second) immunization, mice were inoculated with 10 times the median lethal dose 50% (10 × LD50) of H3N2 virus A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 or A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31. Mice were monitored over a period of 2 weeks following infection for clinical signs, twice-daily weight, and survival. The percent change in weight was calculated based on the pre-infection weight. Animals that lost ≥25% of their total weight were euthanized. To assess viral load in the lungs, a separate group of mice (n = 5/group) were euthanized 2 days post infection.

Statistics

Statistical significance of titration endpoint binding and HAI titer data was defined using a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test at a 95% confidence interval. Statistical comparisons of ELISpot data were performed by two-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons. Statistical comparisons of flow cytometry data were performed by two-tailed unpaired t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Animal care

All animal housing and experimentation were approved by and conducted in accordance with the guidelines set by the National Institutes of Health, the Wistar Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the Bioqual, Inc. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All murine experiments were conducted in accordance with and subsequently performed in Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-certified facilities at The Wistar Institute and Bioqual, Inc.

Results

Synthetic micro-consensus H3 immunogen design and characterization

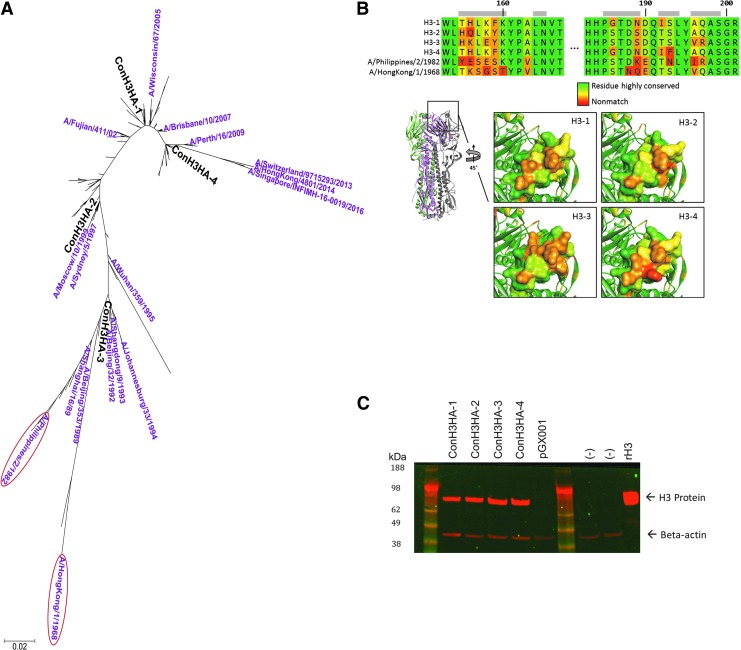

Four synthetic HA H3 immunogens were engineered to elicit immune responses against a breadth of H3N2 viruses. The H3 amino acid sequences from 233 influenza A H3N2 strains, isolated over multiple decades, were aligned to generate a phylogenetic tree. Tree analysis yielded four micro-consensus H3 immunogens (ConH3HA-1, -2, -3, and -4) close enough in sequence to individual isolates for predicted induction of cross-reactive immune responses against diverse H3N2 strains (Fig. 1A) based on prior micro-consensus vaccine design experience with influenza A H1, H5, and H7.13–15 Sequence homology analysis indicated that amino acid sequence identities between these four micro-consensus H3 immunogens range from 93.1% to 98.8%.

Figure 1.

pH3HA consensus vaccine design. (A) Phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood evaluation of hemagglutinin (HA) H3 alignment. The relevant placement of the four micro-consensus H3 DNA immunogens (ConH3HA-1, ConH3HA-2, ConH3HA-3, and ConH3HA-4) are shown in bold black text. Challenge strains used for this study (circled) and H3N2 viruses contained in commercially available seasonal influenza vaccines during the past 30 years are shown. (B) Structural model of HA consensus antigens. Immunogen homology model comparison. Structural models of all four immunogens were generated and compared. Above, sequence alignment of site B region with challenge strains included. Site B residues are indicated with a gray bar. Residues are colored by relative sequence conservation. Below left, HA model of ConH3HA-1 indicating site B on the HA trimer model. Below right, detail of site B of the four comparative models, also colored by relative sequence conservation. (C) In vitro consensus antigen expression. H3 Western blot of lysates from HEK 293T cells transfected with each of four plasmid DNA constructs expressing ConH3HA (ConH3HA-1 through -4). Recombinant protein H3 (rH3), un-transfected cells (–), and cells transfected with plasmid DNA lacking transgene (pGX001) serve as controls.

Comparative models were aligned and superimposed to assess global structural similarity and for epitope comparison purposes between the four micro-consensus H3 immunogens. Unsurprisingly, all models adopted a similar fold with Cα root mean square deviations ranging from 0.30 to 0.63 Å. While overall sequence conservation is high, there are regions on the structures with large local sequence divergence. Site B, a portion of the H3 head region that borders the sialic acid receptor binding site, is one such region and exhibits broad diversity among the four immunogens as a product of the micro-consensus design methodology (Fig. 1B).

A nucleic acid sequence for each synthetic micro-consensus H3 immunogen was developed using in silico DNA codon optimization and RNA optimization algorithms. Each transgene sequence was then de novo synthesized and sub-cloned into a mammalian DNA expression plasmid, such that each plasmid contained a 1,698 bp insert encoding a 566-amino-acid H3 peptide. All four plasmid DNA constructs expressed H3 antigen following transient transfection into human embryonic kidney 293T cells (Fig. 1C). A cocktail containing an equimolar mixture of the four plasmid DNA H3 immunogens was formed to create the pH3HA DNA vaccine.

Breadth of humoral and cellular immune responses following pH3HA immunization

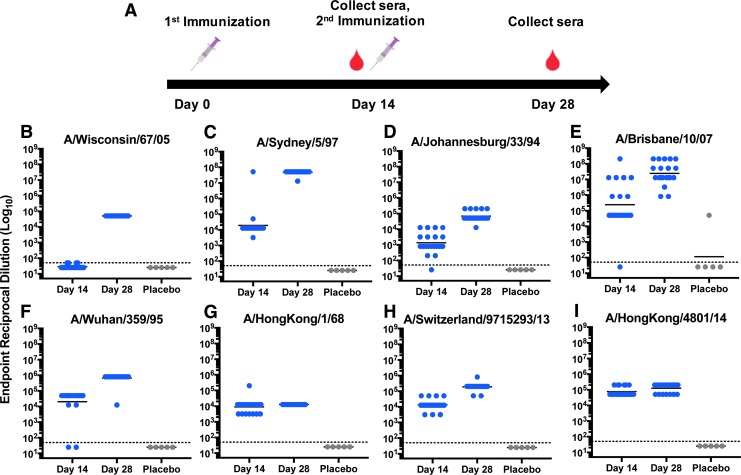

To determine immunogenicity of the pH3HA vaccine, two intramuscular injections of 40 μg plasmid DNA (10 μg of each H3 DNA immunogen) were administered to BALB/c mice over a 2-week interval (Fig. 2A). Each injection was accompanied by EP to facilitate plasmid delivery.16 Humoral responses to specific influenza H3 antigens and influenza viral strains were measured. Each strain was specifically selected to represent the micro-consensus regions of H3, as well as the temporal history of H3N2 infection in humans. One hundred percent (20/20) of the immunized mice developed broad, robust antibody responses against HA, with geometric mean reciprocal endpoint IgG titers ranging from 4.1 log10 to 7.7 log10 following the second dose of pH3HA vaccine (Fig. 2). pH3HA immunization induced host IgG antibodies against distinct HA genetic clades encompassing the history and breadth of seasonal influenza A H3N2 viruses in people. All mice seroconverted against a comprehensive set of HA antigens representing influenza A H3N2 viruses within consensus regions ConH3HA-1 (A/Wisconsin/67/2005), ConH3HA-2 (A/Sydney/5/1997), ConH3HA-3 (A/Johannesburg/33/1994), and ConH3HA-4 (A/Brisbane/10/2007). Additionally, vaccination with pH3HA induced robust IgG antibodies against the emergent 1968 pandemic H3N2 (A/Hong Kong/8/1968) and contemporary H3N2 strains (A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 and A/Hong Kong/4801/2014), which were components of commercially available vaccines from 2015/2016 through 2017/2018. Antibody responses against the majority of H3 antigens were substantial after a single administration of pH3HA, with ≥90% of mice seroconverting against seven of the eight HA after one immunization. pH3HA also induced both IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum).

Figure 2.

pH3HA vaccine induces host antibodies that bind to diverse influenza A H3N2 hemagglutinin (H3) antigens representing all four consensus regions. (A) Schematic of pH3HA immunization schedule. BALB/c mice received 40 μg of pH3HA plasmid DNA cocktail on days 0 and 14. Immune sera were collected following one immunization (day 14) and two immunizations (day 28). (B–I) Reciprocal endpoint mouse IgG binding ELISA titers against diverse recombinant H3 from the viruses indicated following one dose (day 14) and two doses (day 28) of pH3HA (blue). Control mice were inoculated twice (days 0 and 14) with plasmid DNA lacking H3 transgene (gray, placebo). (Geometric mean, n = 20 vaccinated mice/group and n = 5 placebo mice, hashed line indicates starting dilution limit of 1:50).

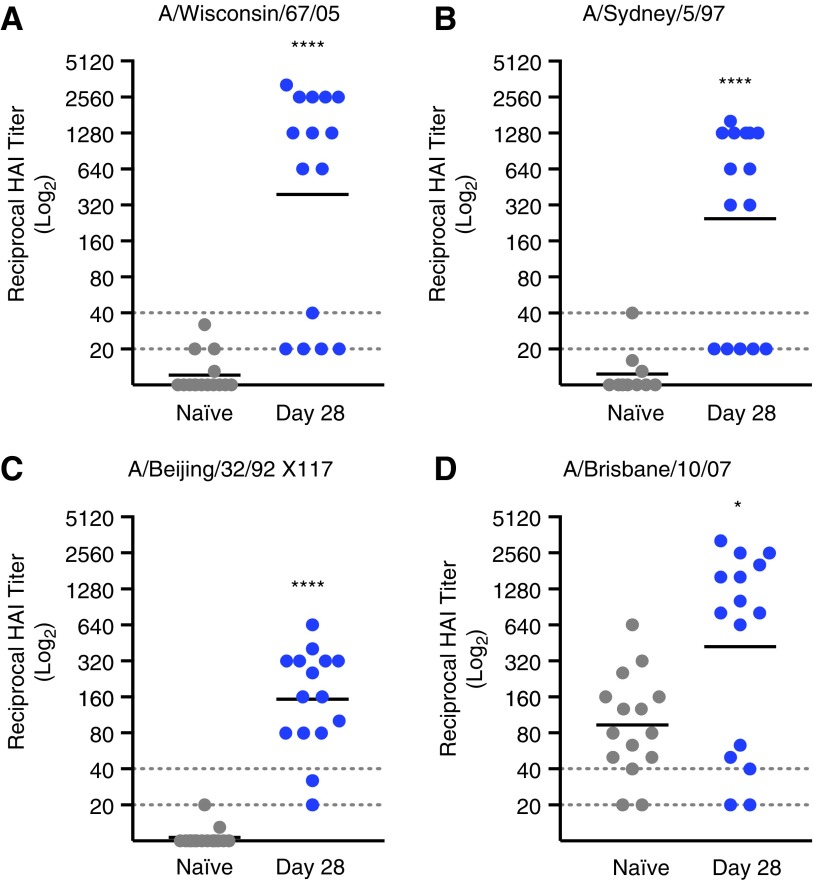

Sera from vaccinated mice demonstrated HAI of viruses representing all four HA micro-consensus regions, highlighting the functional breadth of pH3HA-induced antibody responses against H3N2 (Fig. 3). Two-thirds or more of pH3HA-immunized mice developed HAI titers >1:40 against viruses representing consensus regions ConH3HA-1 (A/Wisconsin/67/2005), ConH3HA-2 (A/Sydney/5/1997), ConH3HA-3 (A/Beijing/32/1992 X117 reassortant virus), and ConH3HA-4 (A/Brisbane/10/2007). Generally, serum HAI antibody dilution titers of 1:40 in humans are associated with a 50% reduction in population risk for influenza infection or disease.17,18 Geometric mean HAI titers in pH3HA-vaccinated mice were >1:150 (Table 1) and significantly greater than in unvaccinated naïve mice (p < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test). Background HAI titers against influenza virus A/Brisbane/10/2007 in naïve mice were inexplicably high. However, pH3HA clearly enhanced HAI titers relative to background (p = 0.03, Mann–Whitney U-test). Vaccinated mice also developed antigen-specific neutralizing antibodies against H3N2 influenza viruses (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Sera from pH3HA-vaccinated mice blocked infection by viruses from consensus regions ConH3HA-1 (A/Wisconsin/67/2005), ConH3HA-2 (A/Sydney/5/1997), and ConH3HA-4 (A/Brisbane/10/2007) at geometric mean dilutions >1:1,000. Functional antibody responses elicited by pH3HA were persistent; mouse sera HAI titers were observed 2 months following the second immunization (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Sera from pH3HA-vaccinated mice inhibit hemagglutination of red blood cells mediated by influenza A H3N2 viruses from all four consensus regions. Mice were immunized twice with pH3HA (days 0 and 14). Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers of sera collected after the second pH3HA immunization (day 28) against H3N2 viruses: (A) A/Wisconsin/67/2005 from consensus region ConH3HA-1; (B) A/Sydney/5/1997 from consensus region ConH3HA-2; (C) reassortant A/Beijing/32/1992 X117 from consensus region ConH3HA-3; and (D) A/Brisbane/10/2007 from consensus region ConH3HA-4. (Geometric mean, n = 15 mice/group, hashed lines indicate starting serum dilution limit of 1:20 and clinically relevant HAI titer of 1:40, Mann–Whitney U-test, *p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001 relative to naïve).

Table 1.

Antibody response to pH3HA immunization

| H3N2 virus/H3 antigen | Consensus regiona | H3 variation from consensus amino acid sequence (%)b | Geometric mean endpoint IgG binding titer (reciprocal, Log10)c | Geometric mean HAI titerc | Geometric mean MN titerd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/Wisconsin/67/05 | 1 | 1.2 | 4.7 | 1:390 | >1:1,689 |

| A/Sydney/5/97 | 2 | 1.4 | 7.7 | 1:240 | >1:1,114 |

| A/Wuhan/359/95 | 3 | 2.1 | 5.8 | … | … |

| A/Johannesburg/33/94 | 3 | 1.8 | 4.8 | … | … |

| A/Beijing/32/92 (X117) | 3 | 1.1 | … | 1:150 | … |

| A/Hong Kong/1/68 (X31) | 3 | 9.5 | 4.1 | … | <1:20 |

| A/Philippines/2/82 (X79) | 3 | 4.2 | … | … | <1:20 |

| A/Brisbane/10/07 | 4 | 0.5 | 7.4 | 1:420 | >1:2,560 |

| A/Switzerland/9715293/13 | 4 | 3.7 | 5.3 | … | … |

| A/Hong Kong/4801/14 | 4 | 3.5 | 5.1 | … | … |

Viruses listed in bold were utilized in mouse challenge studies.

Micro-consensus ConH3HA region (ConH3HA-1, -2, -3, or -4).

Percentage of total amino acid residues that differ between viral H3 sequence and that of the most similar micro-consensus ConH3HA amino acid sequence.

Data shown following two immunizations (days 0 and 14) with pH3HA, corresponding to data shown in Fig. 3 (n = 15 mice/group).

Sera MN titers following two immunizations (days 0 and 14) with pH3HA, corresponding to data shown in Supplementary Fig. S2 (n = 10 mice/group).

H3, influenza A H3N2 hemagglutinin; IgG, immunoglobulin G; HAI, hemagglutination inhibition; MN, micro-neutralization; …, assay was not performed against this antigen/virus.

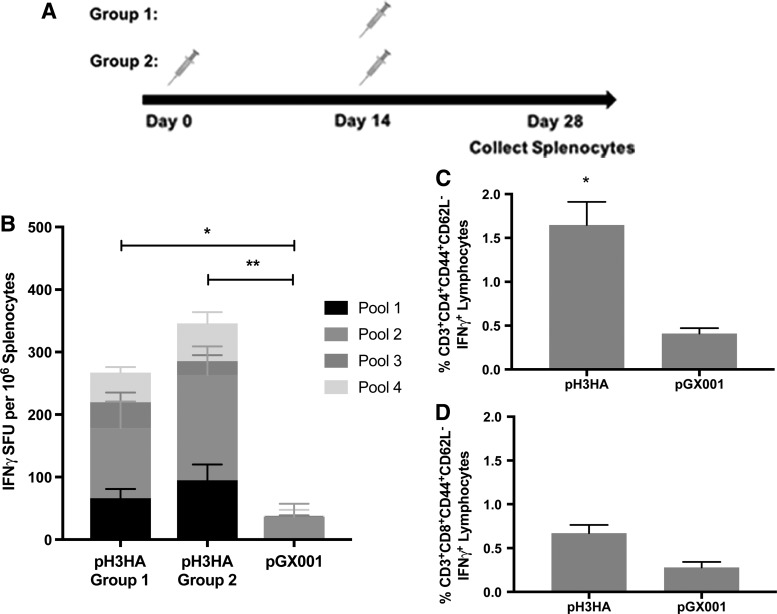

In addition to broad antibody responses elicited by pH3HA immunization, vaccinated mice developed antigen-specific cellular immune responses. Cytokine IFN-γ responses against H3 peptides developed in mice following a single inoculation with pH3HA (Fig. 4B). The cellular IFN-γ response was predominantly directed against peptides from receptor-binding subunit HA1 of H3 (represented by linear peptide pool 2; Fig. 4B) and appeared to be mediated by CD4+ T cells as opposed to CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4.

Cellular responses to pH3HA immunization. (A) BALB/c mice were immunized once (group 1) or twice (group 2) with pH3HA, or with empty plasmid DNA (pGX001). Splenocytes were collected 2 weeks following the final immunization. (B) Enzyme-linked immunospot cellular interferon gamma cytokine responses to linear pools of peptides representing the full HA consensus sequence ConH3HA-1. (Mean ± standard error, n = 5 mice/group, two-way analysis of variance of total spot counts, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.) Memory CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T-cell responses to consensus H3-1 peptides after two immunizations with pH3HA (group 2, day 28). (Mean ± standard error, n = 5 mice/group, t-test of percent cytokine-positive gated cells, *p < 0.05.).

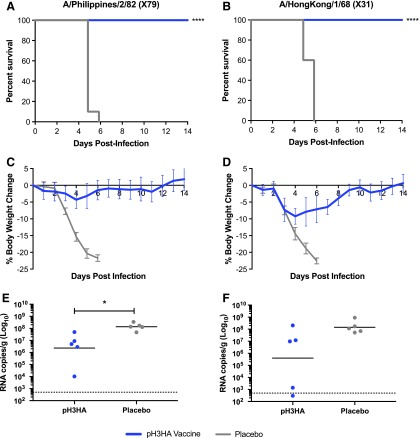

pH3HA immunization protects mice from lethal H3N2 challenge

Next, the protective efficacy of pH3HA vaccination was defined. BALB/c mice received two 40 μg pH3HA immunizations via EP at a 2-week interval, a repeat of the experiment in Fig. 2A. Mice were challenged 2 weeks following the second immunization with one of two reassortant mouse-adapted influenza viruses: A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 or A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31. A/Philippines/2/1982 and A/Hong Kong/1/1968 share only 91.5% H3 amino acid sequence identity and differ by 9/20 amino acid residues in H3 antigenic site B. Additionally, the H3 amino acid sequences of A/Philippines/2/1982 and A/Hong Kong/1/1968 differ by 4.2% and 9.5%, respectively, from the closest micro-consensus H3 immunogen (ConH3HA-3; Table 1).

Despite the lack of exact H3 match between challenge virus and vaccine DNA immunogens, the pH3HA micro-consensus vaccine offered full protection against H3 influenza lethality in mice (10/10; Fig. 5A and B). pH3HA-vaccinated mice survived intranasal challenge with 10 × LD50 of virus, whereas mice treated with an empty plasmid DNA placebo succumbed to infection within 6 days of exposure to influenza. Mice challenged with A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 exhibited a mean maximum weight loss of 4% (range 0–7%) and mice challenged with A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31 developed a mean maximum weight loss of 9% (range 7–11%; Fig. 5C and D). Clinical signs of influenza infection in vaccinated mice resolved within 7 days of A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 and 11 days of A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31 exposure, concomitant with weight recovery. Geometric mean viral loads were 1.5- to 2.5-log10 lower in pH3HA-immunzed mice than controls, reaching statistical significance in A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 infection (Fig. 5E and F).

Figure 5.

pH3HA-vaccinated mice are protected against lethal challenge with distinct influenza A H3N2 viruses. (A and B) Survival, (C and D) weight loss, and (E and F) lung viral loads following H3N2 influenza A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 (left, A, C, and E) or A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31 (right, B, D, and F) infection in mice vaccinated with pH3HA (blue) or empty plasmid DNA (pGX001, placebo, gray). (A–D) Ten BALB/c mice were immunized twice (days 0 and 14) and challenged 2 weeks later (day 28) with 10 times the median lethal dose 50% (10 × LD50) intranasal mouse-adapted A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 (A and C) or A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31 (B and D). Animals were monitored over a period of 14 days post infection for survival (Mantel–Cox log rank test, ****p < 0.0001) and weight loss (mean ± standard deviation). (E and F) Five mice were immunized twice (days 0 and 14) and challenged 2 weeks later with 10 × LD50 intranasal mouse-adapted A/Philippines/2/1982 X79 (E) or A/Hong Kong/1/1968 X31 (F). Lungs were harvested 2 days post infection for determination of tissue viral loads by quantitative polymerase chain reaction of viral RNA (geometric mean, n = 5 mice/group, Mann–Whitney U-test, *p < 0.05).

Discussion

Morbidity caused by seasonal influenza A H3N2 is generally more severe than that caused by seasonal influenza A H1N1 or influenza-B.19 Commercial vaccine efficacy against H3N2 in the most recent 2017/2018 influenza season was low, contributing to pneumonia- and influenza-associated deaths above the epidemic threshold.20,21 The high diversity of surface epitopes on H3N2 viruses is a challenge for immune recognition and traditional vaccine efficacy. H3N2 viral evolution at the genomic level is relatively continuous compared to the punctate nature of antigenic drift, indicating H3N2 dynamics are shaped by a complex combination of rapid viral mutation, reassortment, natural selection in hosts, and epidemiology.22,23 The WHO recommendations for H3N2 components of inactivated/live-attenuated influenza vaccines have been updated 11 (Northern hemisphere) or 12 (Southern hemisphere) times since the 1998/1999 season when commercial vaccines became widely available. Furthermore, while commercially available vaccines are designed and certified by their ability to induce functional humoral responses (particularly HAI) that correlate well with protection in children and adults, evidence suggests cellular responses are a key correlate of influenza vaccine efficacy in elderly patients (reviewed in McElhaney et al.24). There is a clear need for more comprehensive immune protection against H3N2 and improvements in rapid selection and deployment against emergent viral strains.

Here, an engineered DNA vaccine, pH3HA, is presented with protective efficacy against lethal challenge with two distinct influenza A H3N2 viruses in mice. pH3HA protected mice against severe H3N2 pathogenesis, despite the lack of exact sequence match between H3 vaccine immunogen and H3 in each challenge virus, demonstrating the strength of the synthetic micro-consensus approach to broad vaccine design. Functional antibodies elicited by pH3HA immunization targeted contemporary H3N2 antigens, while also demonstrating breadth against viruses that circulated prior to the “A/Fujian-like” viral shift in the early 21st century. Despite the finding that pH3HA-vaccinated mice are fully protected against lethal H3N2 infection, not all vaccinated mice display strong HAI titers against H3N2, and not all H3N2 are neutralized by vaccine-induced antibodies. This observation likely suggests that antigen-specific humoral and cellular immunity are acting in concert to protect against lethal challenge. pH3HA-vaccinated mice developed H3-antigen-specific cellular IFN-γ responses. Notably, protective T-cell responses may be critical to functional influenza immunity in elderly populations.25 Further studies, including T-cell epitope analyses and immune cell depletion studies, are warranted to determine the relative potency and protective efficacy of humoral versus cellular responses following pH3HA immunization.

Contemporary potent antiviral DNA vaccines have demonstrated safety, tolerability, and efficacy in human clinical trials.26 DNA vaccines against influenza A have been evaluated in clinical safety and/or efficacy studies, both alone and as part of a prime-boost regimen.27–29 Influenza A DNA vaccines with broad immunogenicity and preclinical efficacy have been previously developed in animal challenge studies with subtypes H1N1, H5N1, and H7N9.13,15,30,31 Plasmid DNA circumvents issues of pre-existing anti-vector serology, genomic integration, and mammalian cell culture/purification processes associated with viral-vectored gene therapy vaccine approaches. Recent studies suggest mutations that abrogate H3 antigenicity can be found after serial passage of H3N2 viruses in cell culture and/or eggs used for conventional influenza vaccines.9,10 Further studies are needed to determine if direct in vivo H3 immunogen expression elicited by DNA vaccine inoculation circumvents possible manufacturing limitations of inactivated/live-attenuated influenza vaccines. Synthetic DNA vaccines are relatively simple and rapid to manufacture and can be developed for stability in the absence of a storage cold chain. The accelerated pace of DNA vaccine development relative to conventional vaccine platforms was previously highlighted by design and initiation of a micro-consensus plasmid construct seed stock production against influenza A H7N9 in just a few days.31 Furthermore, a Zika virus prME DNA vaccine was evolved from concept to manufacturing and initiation of a Phase I clinical study in <7 months32,33 with induction of robust clinical immunity, illustrating the speed and potency of the synthetic DNA platform.

The pH3HA DNA vaccine represents a unique micro-consensus approach to elicit comprehensive immune responses to antigenically diverse seasonal influenza A H3N2 viruses, toward an overarching goal to circumvent the need for annual vaccine re-formulations and protect against novel H3N2 viruses. Further studies are needed to determine if this pH3HA can be studied in combination approaches targeting H1N113 or emergent avian influenza viruses15,30,31 for heterosubtypic DNA-based pan-influenza A prevention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Kaela Parkhouse and Seth J. Zost of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine provided help with the assay design. Spencer Bianco assisted in performing in vitro experiments.

Author Disclosure

K.B., J.Y., C.R., and B.G. are employees of Inovio Pharmaceuticals and as such receive salary and benefits, including ownership of stock and stock options, from the company. D.W. has received grant funding, participates in industry collaborations, has received speaking honoraria, and has received fees for consulting, including serving on scientific review committees and board services. Remuneration received by D.W. includes direct payments or stock or stock options, and in the interest of disclosure, he notes potential conflicts associated with this work with Inovio and possibly others. In addition, he has a patent DNA vaccine delivery pending to Inovio.

References

- 1.Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 2018;391:1285–1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koel BF, Burke DF, Bestebroer TM, et al. Substitutions near the receptor binding site determine major antigenic change during influenza virus evolution. Science 2013;342:976–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Mello T, Brammer L, Blanton L, et al. Update: infleunza activity—United States, September 28, 2014–February 21, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:206–212 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers BS, Parkhouse K, Ross TM, et al. Identification of hemagglutinin residues responsible for H3N2 antigenic drift during the 2014–2015 influenza season. Cell Rep 2015;12:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweiger B, Bruns L, Meixenberger K. Reassortment between human A(H3N2) viruses is an important evolutionary mechanism. Vaccine 2006;24:6683–6690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes EC, Ghedin E, Miller N, et al. Whole-genome analysis of human influenza A virus reveals multiple persistent lineages and reassortment among recent H3N2 viruses. PLoS Biol 2005;3:1579–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghedin E, Sengamalay NA, Shumway M, et al. Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution. Nature 2005;437:1162–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity—United States and worldwide, 2003–04 season, and composition of the 2004–05 influenza vaccine. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:547–550 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin Y, Wharton SA, Whittaker L, et al. The characteristics and antigenic properties of recently emerged subclade 3C.3a and 3C.2a human influenza A(H3N2) viruses passaged in MDCK cells. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2017;11:263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zost SJ, Parkhouse K, Gumina ME, et al. Contemporary H3N2 influenza viruses have a glycosylation site that alters binding of antibodies elicited by egg-adapted vaccine strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:12578–12583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frey A, Di Canzio J, Zurakowski D. A statistically defined endpoint titer determination method for immunoassays. J Immunol Methods 1998;221:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO manual on animal influenza diagnosis and surveillance. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/68026 (last accessed April29, 2018)

- 13.Yan J, Morrow MP, Chu JS, et al. Broad cross-protective anti-hemagglutination responses elicited by influenza microconsensus DNA vaccine. Vaccine 2018;36:3079–3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laddy DJ, Yan J, Corbitt N, et al. Immunogenicity of novel consensus-based DNA vaccines against avian influenza. Vaccine 2007;25:2984–2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laddy DJ, Yan J, Kutzler M, et al. Heterosubtypic protection against pathogenic human and avian influenza viruses via in vivo electroporation of synthetic consensus DNA antigens. PLoS One 2008;3:e2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sardesai NY, Weiner DB. Electroporation delivery of DNA vaccines: prospects for success. Curr Opin Immunol 2011;23:421–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng S, Fang VJ, Ip DKM, et al. Estimation of the association between antibody titers and protection against confirmed influenza virus infection in children. J Infect Dis 2013;208:1320–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coudeville L, Bailleux F, Riche B, et al. Relationship between haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody titres and clinical protection against influenza: development and application of a bayesian random-effects model. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaji M, Watanabe A, Aizawa H. Differences in clinical features between influenza A H1N1, A H3N2, and B in adult patients. Respirology 2003;8:231–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017–18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:180–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Budd AP, Wentworth DE, Blanton L, et al. Update: influenza activity—United States, October 1, 2017–February 3, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:169–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Nelson MI, et al. The genomic and epidemiological dynamics of human influenza A virus. Nature 2008;453:615–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DJ, Lapedes AS, De Jong JC, et al. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science 2004;305:371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McElhaney JE, Kuchel GA, Zhou X, et al. T-cell immunity to influenza in older adults: a pathophysiological framework for development of more effective vaccines. Front Immunol 2016;7:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McElhaney JE, Beth Barry M, Ewen C, et al. T cell responses are better correlates of vaccine protection in the elderly. J Immunol 2006;176:6333–6339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2b trial. Lancet 2015;386:2078–2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledgerwood JE, Wei C-J, Hu Z, et al. DNA priming and influenza vaccine immunogenicity: two Phase 1 open label randomised clinical trials. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:916–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith LR, Wloch MK, Ye M, et al. Phase 1 clinical trials of the safety and immunogenicity of adjuvanted plasmid DNA vaccines encoding influenza A virus H5 hemagglutinin. Vaccine 2010;28:2565–2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones S, Evans K, McElwaine-Johnn H, et al. DNA vaccination protects against an influenza challenge in a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled Phase 1b clinical trial. Vaccine 2009;27:2506–2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laddy DJ, Yan J, Khan AS, et al. Electroporation of synthetic DNA antigens offers protection in nonhuman primates challenged with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. J Virol 2009;83:4624–4630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan J, Villarreal DO, Racine T, et al. Protective immunity to H7N9 influenza viruses elicited by synthetic DNA vaccine. Vaccine 2014;32:2833–2842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tebas P, Roberts CC, Muthumani K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an anti–Zika virus DNA vaccine—preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2017. October 4 [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kudchodkar SB, Choi H, Reuschel EL, et al. Rapid response to an emerging infectious disease—lessons learned from development of a synthetic DNA vaccine targeting Zika virus. Microbes Infect 2018. March 17 [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1016/J.MICINF.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.