Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to identify specific factors (gender, race, provider type) that were significantly associated with patient receipt of an opioid prescription following a dental diagnosis.

Methods

Medicaid claims for thirteen US states (Truven Health MarketScan© database) dated between 2013–2015 were used in this study. Dental and oral health-related conditions were identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 520.0 through 529.9.

Results

More than 890,000 Medicaid patients had a primary dental diagnosis with 23% receiving an opioid within 14 days of a dental diagnosis. Women were 50% more likely to receive an opioid for pain management of a dental condition than men (OR=1.53; 95% CI:1.52–1.55); Non-Hispanic whites and African-Americans were around twice more likely to receive opioids than Hispanics (OR=2.11; 95% CI:2.05–2.17 and OR=1.92; 95% CI:1.86–1.98) respectively. Patients receiving care in an emergency department were nearly five times more likely to receive an opioid prescription than patients treated by a dentist (OR=4.66; 95% CI:4.59–4.74). Patients diagnosed with a dental condition were 2.5 times as likely to receive an opioid from a nurse practitioner than from a dentist (OR=2.64; 95% CI:2.57–2.70). Opioid use was substantially higher among African-American women (OR=3.29; 95% CI:3.18–3.40) and Non-Hispanic white women (OR=3.24; 95% CI:3.14–3.35) as opposed to Hispanic women.

Conclusions

Opioid prescribing patterns differ depending on patient race/ethnicity, gender, and provider source in patients with a dental diagnosis in the US.

Keywords: Opioid, Medicaid, Oral Diagnosis, Drug Prescriptions

INTRODUCTION

Over the last ten years, the United States (US) has experienced increasing rates of opioid use, abuse, and overdose deaths. This concern culminated in a presidential declaration in 2017 that the opioid crisis was a national public health emergency1. The burden of the opioid epidemic impacts all aspects of the health care delivery system: patients, providers, and insurers. An estimated 1 in 5 patients with non-cancer, pain-related diagnoses are prescribed opioids in office-based settings2. Among all non-cancer providers, dentists provide the second fewest opioid prescriptions, after general practitioners, family medicine, primary care and internists3. Opioid prescribing by dentists is estimated to be 12% of the overall annual opioid prescription total2, 4; and 1,500 deaths annually may be attributable to unused opioids originally prescribed by dentists for therapeutic purposes5. The overall burden is likely higher for management of acute dental pain as emergency department (ED) providers also prescribe opioid analgesics for nontraumatic dental conditions (NTDCs)6–10.

Oral pain can be acute, often occurring abruptly and intensely11. Consequently, relief of oral pain is often sought at emergency and urgent care facilities, leaving emergency providers to prescribe treatment that is only palliative and non-definitive12. Consideration on how to treat oral and dental pain with an opioid includes a number of factors, such as provider experience, professional guidelines, the patient’s own pain perception, communication regarding the pain experience between patient and the treatment team, and an individual pain assessment13.

Non-white race/ethnic groups are less likely to receive an opioid prescription for any condition13. This is frequently due to incorrect provider perception that when minorities present to the ED for pain, they are more likely to be drug-seeking rather than suffering from actual pain, relative to a Non-Hispanic white patient with a similar, pain-related complaint14, 15. Biological differences in pain perception by racial minorities may lead to further under treatment for pain16. Hispanics are half as likely as Non-Hispanic whites to receive no analgesic medication during an ED visit even after controlling for patient characteristics within both groups17. Non-Hispanic whites are 60% more likely to receive opioid analgesics than African-Americans18.

Generally, women are more likely to be prescribed an opioid for dental pain than men during an emergency visit18. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that opioid prescribing rates for any diagnosis, regardless of cause, is higher in women than men19. There may be a physiologic explanation for this difference as women consistently show a greater sensitivity to pain when compared to men20. Differences observed in receipt of opioid prescriptions are not always accounted for when controlling for demographic factors. While previous research has correlated gender differences in pain intensity, these differences are not always seen in opioid prescriptions provided to patients; sometimes females are provided more, especially stratified by race/ethnicity, and sometimes males receive more prescriptions. Differences in drug-prescribing patterns could be caused by an unconscious bias among health providers21. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that attributing opioid prescription disparities due to providers’ personal beliefs, type of provider, and patient demographics is inconclusive, at best22.

Information on the opioid prescribing practices of emergency health care providers for dental pain is sparse23. Moreover, there is no information that has assessed patient gender, race/ethnicity or provider differences for opioid prescriptions for any dental diagnosis among low-income patients, such as Medicaid recipients. The main aim of this study is to investigate differences in opioid receipt for dental diagnoses by key demographic factors based on outpatient claims data for Medicaid-enrolled children and adults; and to determine if these differences are influenced by the type of provider or dental diagnosis.

METHODS

Data Source and Sample Selection

This retrospective study uses de-identified medical and pharmacy Medicaid claims data for calendar years 2013 through 2015 from the Truven MarketScan Database Multi-state Medicaid core data set (https://truvenhealth.com/markets/life-sciences/products/data-tools/marketscan-databases). This database contains individual claims information from 2.8 million individuals from 13 US states. To protect individual confidentiality, this dataset does not contain geographic identifiers or personally-identifiable information. Access to this database was made possible through a research collaboration with the DentaQuest Institute, who obtained the data access license.

The data included person-level information (e.g., age, gender and enrollment period) and claim-level data (e.g., outpatient pharmacy prescription claims) for all claims between January 1, 2013 to September 30, 2015 (due to the change from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM on October 1, 2015). Outpatient pharmacy claims were searched for opioid-containing medications using the therapeutic class “opioid analgesics group”. This group of drugs includes drugs derived from opium, including morphine, as well as semi-synthetic and synthetic drugs such as hydrocodone, oxycodone and fentanyl.

We generated a record of all patients who presented to an outpatient facility for any dental/oral related care using Streamline’s Clinical Looking Glass (https://www.streamlinehealth.net/patient-care/clinical-analytics/). This analytical tool is designed to help organize and generate healthcare claims data and it allows create and comparison of, two separate cohorts using data from the Truven Multi-state Medicaid database. The first cohort contained patients who had dental diagnosis. Consistent with prior research, dental diagnoses were identified as those claims with an ICD-9-CM code between 520.0 and 529.912. Demographic variables included age in years, gender, race/ethnicity, and provider type. The second cohort was built using on prescription claims records who received a prescription for any opioid analgesic with 14 days of the primary dental diagnosis. Patients were restricted to only those enrollees with continuous enrollment of 0–14 days in a Medicaid plan that included prescription drug coverage. Both cohorts were matched using the unique patient identifier based on the index date of the event of interest and duplicates were removed to form the analytical dataset.

Analytical Variables

Prescription opioids was the primary outcome variable and was categorized dichotomously (received an opioid within 14 days of primary dental diagnosis, yes or no). The primary dental diagnosis was generally based on four categories: diseases of pulp and periapical tissues, disease of soft tissues of the oral cavity, diseases of gingival periodontal tissues, and diseases of hard tissue/jaw. The provider source was categorized into Emergency Departments (EDs), Dentist, Medical Specialist, Nurse Practitioner, and Other, which refers to any other provider source identified in the data set. Additional independent variables included age group, gender, and race/ethnicity. Race/ethnicity was categorized as Hispanics, Non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, and Other race/ethnicities.

Data Analysis

Frequencies and proportions of patients with an opioid prescription were calculated from the total cohort of dental diagnoses identified. These were stratified by age group, gender, race/ethnicity, provider type and dental diagnosis type. The proportions were adjusted to the total cohort within the Medicaid database. Logistic regression models were produced to ascertain the association of the independent variables (provider type, gender and race/ethnicity) with the dependent variable, receipt of an opioid. Interactions were investigated and subsequent models were produced by stratifying on gender and care/ethnicity. Additional analyses were conducted to explore possible influence of provider source and diagnosis types on the differential effects observed by gender and race/ethnicity. We did investigate potential effects that specific dental diagnoses may have on receipt of an opioid prescription, and we found that to be non-significant; thus, dental diagnosis type was not included in our final multivariable models. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

RESULTS

From total of 28,151,790 Medicaid beneficiaries with relevant claims information between January 1, 2013 and September 30, 2015, we identified 891,720 individuals who had a primary diagnosis of a dental or oral-related condition. Among these persons, 209,296 (23.4%) filled an opioid prescription within 14 days of their dental diagnosis (Table 1). In this group of Medicaid patients with a dental diagnosis, slightly more than half were under 18 years (56.3%) old and Non-Hispanic white (53.9%). Among all patients with a primary dental diagnosis, approximately 24% had a Medicaid claim from a dentist and 23% had a claim from an emergency department. Among patients receiving an opioid within 14 days of a dental diagnosis, the larger proportions were 19–29-year-olds (30.3%), women (65.8%), Non-Hispanic whites (57.8%), and those receiving care from ED providers (36.8%).

Table 1.

Distribution of Medicaid patients receiving opioids within 14 days of a dental Diagnosis By selected characteristics.

| Patients with Dental Diagnosis | Patients with Opioid Prescriptions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | %* | %# | |

| Total | 891,720 | 100.0 | 209,296 | 100.0 | 23.4 |

| Age group in years | |||||

| <18 | 501,912 | 56.3 | 50,008 | 23.9 | 10.2 |

| 19–29 | 132,770 | 14.9 | 63,436 | 30.3 | 47.8 |

| 30–39 | 101,929 | 11.4 | 49,349 | 23.6 | 48.4 |

| 40–49 | 60,914 | 6.8 | 24,702 | 11.8 | 40.6 |

| 50–64 | 65,387 | 7.3 | 20,567 | 9.8 | 31.5 |

| 65> | 27,784 | 3.12 | 1,234 | <1.0 | 3.0 |

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 380,286 | 42.7 | 71,509 | 34.2 | 18.8 |

| Females | 511,434 | 57.4 | 137,787 | 65.8 | 26.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Whites | 480,208 | 53.9 | 120,903 | 57.8 | 25.2 |

| African-American | 218,453 | 24.5 | 54,025 | 25.8 | 24.7 |

| Hispanics | 76,809 | 8.6 | 7,486 | 3.6 | 9.8 |

| Other Ethnicities | 116,250 | 13.0 | 26,882 | 12.8 | 23.1 |

| Provider source | |||||

| Emergency Department | 200,863 | 22.5 | 77,043 | 36.8 | 38.4 |

| Dentist | 209,469 | 23.5 | 22,612 | 10.8 | 10.8 |

| Medical Specialist | 217,370 | 24.4 | 44,013 | 21.0 | 20.2 |

| Nurse Practitioner | 43,910 | 4.9 | 11,495 | 5.5 | 26.2 |

| Other Sources | 114,755 | 12.9 | 19,540 | 9.3 | 16.9 |

| Unknown | 105,353 | 11.8 | 34,593 | 16.5 | 32.8 |

| Dental Diagnoses | |||||

| Diseases of hard tissues: tooth | 634,416 | 71.1 | 150,683 | 72.0 | 23.8 |

| Pulp and Periapical diseases | 78,619 | 8.8 | 34,417 | 16.4 | 43.8 |

| Diseases of soft tissues of oral cavity | 27,828 | 3.1 | 5,958 | 2.8 | 21.3 |

| Gingival and periodontal diseases | 150,857 | 16.9 | 18,238 | 8.7 | 12.1 |

Notes:

percent of opioid prescriptions within a cohort characteristic (i.e., column percent);

percent of opioid prescriptions for a specific category within cohort characteristic (i.e., row percent)

Only 3% of adults age 65 and older received an opioid following a dental diagnosis, whereas 48.4% of patients age 30–39 received an opioid. There was no observed difference between African-American and Non-Hispanic white patients with a filled opioid prescription for a dental diagnosis (25%), whereas only 10% of Hispanics received an opioid prescription. About 38% of patients with a dental diagnosis provided by an emergency department provide received an opioid within 14 days of a diagnosis, whereas only about 11% of patients with a dental diagnosis provided by a dentist received an opioid. About a quarter of patients with a dental diagnosis provided by a nurse practitioner received an opioid prescription (26.2%) and 20% of patients seen by a medical specialist received an opioid following a dental diagnosis. Although 72% of all opioid prescriptions for a dental diagnosis was provided for diseases of hard tissue and teeth, only one in four receiving this diagnosis were prescribed an opioid, whereas 44% of all pulp and periapical diagnoses received an opioid.

Women were more likely (OR=1.53, 95% CI, 1.52–1.55) to fill an opioid prescription for any dental diagnosis than men after controlling for age, race/ethnicity, and provider source (Table 2). Non-Hispanic whites and African-American were two times more likely to receive an opioid than Hispanics (OR=2.11, 95% CI, 2.05–2.17 and OR=1.88, 95% CI, 1.83–1.93) respectively. Emergency departments prescribed opioid medications almost 5 times more often (OR=4.66, 95% CI, 4.59–4.74) than a dentist and nurse practitioners prescribed them nearly three times as often (OR=2.64, 95% CI, 2.57–2.70) compared to a dentist. When stratifying by race/ethnicity and gender (Table 3), receipt of opioids for any dental diagnosis was higher among African-American women (OR=3.29, 95% CI, 3.18–3.40) and Non-Hispanic white women (OR=3.24, 95% CI, 3.14–3.35) than for Hispanic women. African American men were less likely to receive an opioid compared to Non-Hispanic white men (OR=0.88, 95% CI, 0.86–0.90).

Table 2.

Multivariable regression results for Medicaid patients receiving opioids within 14 days of a dental diagnosis.

| Reference | OR* | 95% CI# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider source | Emergency Department | Dentist | 4.66 | 4.59 | 4.74 |

| Medical Specialist | Dentist | 1.98 | 1.94 | 2.01 | |

| Nurse Practitioner | Dentist | 2.64 | 2.57 | 2.70 | |

| Other Sources | Dentist | 1.57 | 1.53 | 1.60 | |

| Gender | Female | Male | 1.53 | 1.52 | 1.55 |

| Race/ethnicity | White | Hispanic | 2.11 | 2.05 | 2.17 |

| African-American | Hispanic | 1.88 | 1.83 | 1.93 | |

| Others | Hispanic | 1.92 | 1.86 | 1.98 | |

Dependent variable is receipt of an Opioid and adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, and provider source;

OR= Odds Ratio;

Confidence Interval

Table 3.

Multivariable regression results for Medicaid patients receiving opioids by race/ethnicity stratified by gender.

| Reference | Gender | OR* | 95% CI# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | African-American | Hispanic | Female | 3.29 | 3.18 | 3.40 |

| African-American | Other | Female | 1.23 | 1.21 | 1.26 | |

| African-American | White | Female | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Female | 2.67 | 2.58 | 2.77 | |

| White | Hispanic | Female | 3.24 | 3.14 | 3.35 | |

| Others | White | Female | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.84 | |

| African-American | Hispanic | Male | 2.47 | 2.37 | 2.57 | |

| African-American | Others | Male | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.86 | |

| African-American | White | Male | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.90 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Male | 2.96 | 2.84 | 3.09 | |

| White | Hispanic | Male | 2.80 | 2.70 | 2.92 | |

| Others | White | Male | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.08 | |

Dependent variable is receipt of an Opioid and adjusted for, gender, race/ethnicity, and provider source;

OR= Odds Ratio;

Confidence Interval

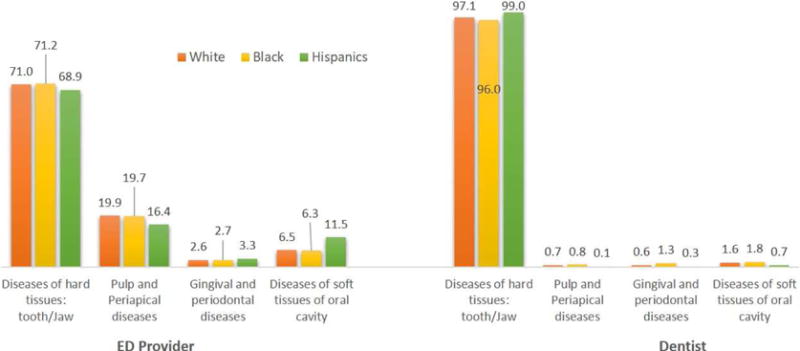

Following stratification by provider source (Table 4), African Americans and whites were more likely to receive an opioid when diagnosed at an emergency department compared to Hispanic patients (OR=1.69, 95% CI, 1.59–1.81 and OR=2.03, 95% CI, 1,91–2.16) respectively. African American patients were 50% more likely to receive an opioid following a dental diagnosis by a dentist compared to Non-Hispanic white patients (OR=1.53, 95% CI, 1.47–1.58) and were nearly three times more likely to receive an opioid by a dentist compared to Hispanic patients (OR=2.81, 95% CI 2.68–2.96). Figure 1 and 2 shows the percentage of opioid receipts following select dental diagnoses by gender and race/ethnicity stratified by ED providers and dentists. Overall, there was no differences observed by gender and race/ethnic differences in receipt of opioid prescriptions by the two provider types, but there were differences between the two providers. For example, ED providers are less likely to prescribe an opioid for diseases of the hard tissue, teeth, and jaws and more for pulp and periapical conditions compared to dentists regardless of the gender or race/ethnicity of the patient.

Table 4.

Multivariable regression results for Medicaid patients receiving opioids by race/ethnicity stratified by provider source.

| Reference | Provider source | OR* | 95% CI# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | African-American | Others | Emergency Department | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.94 |

| African-American | White | Emergency Department | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.85 | |

| African-American | Hispanic | Emergency Department | 1.69 | 1.59 | 1.81 | |

| Others | White | Emergency Department | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.94 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Emergency Department | 1.85 | 1.74 | 1.98 | |

| White | Hispanic | Emergency Department | 2.03 | 1.91 | 2.16 | |

| African-American | Others | Medical Specialist | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.09 | |

| African-American | White | Medical Specialist | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.96 | |

| African-American | Hispanic | Medical Specialist | 1.95 | 1.85 | 2.06 | |

| Others | White | Medical Specialist | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.92 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Medical Specialist | 1.85 | 1.75 | 1.97 | |

| White | Hispanic | Medical Specialist | 2.09 | 1.98 | 2.20 | |

| African-American | Others | Nurse Practitioner | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.17 | |

| African-American | White | Nurse Practitioner | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.20 | |

| African-American | Hispanic | Nurse Practitioner | 2.16 | 1.91 | 2.44 | |

| Others | White | Nurse Practitioner | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.13 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Nurse Practitioner | 1.98 | 1.74 | 2.26 | |

| White | Hispanic | Nurse Practitioner | 1.89 | 1.67 | 2.13 | |

| African-American | Others | Other Sources | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.86 | |

| African-American | White | Other Sources | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.58 | |

| African-American | Hispanic | Other Sources | 2.45 | 2.18 | 2.75 | |

| Others | White | Other Sources | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.73 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Other Sources | 3.00 | 2.66 | 3.40 | |

| White | Hispanic | Other Sources | 4.36 | 3.89 | 4.89 | |

| African-American | Others | Dentist | 1.71 | 1.63 | 1.81 | |

| African-American | White | Dentist | 1.53 | 1.47 | 1.58 | |

| African-American | Hispanic | Dentist | 2.81 | 2.68 | 2.96 | |

| Others | White | Dentist | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.93 | |

| Others | Hispanic | Dentist | 1.64 | 1.55 | 1.74 | |

| White | Hispanic | Dentist | 1.85 | 1.77 | 1.93 | |

Dependent variable is receipt of an Opioid and adjusted for, gender, race/ethnicity, and provider source;

OR= Odds Ratio;

Confidence Interval

Figure 1.

Percent of opioid prescriptions following select dental diagnosis by gender and stratified by provider source.

Figure 2.

Percent of opioid prescriptions following select dental diagnosis by race and stratified by provider source.

DISCUSSION

One of the more difficult challenges for healthcare providers is pain management. Dental pain is intense and localized11 which makes it difficult to manage in ways that are unlike other non-cancer pains experienced by patients. Care is sought for most dental complaints due to sensitivity or pain in the teeth or soft tissues in the oral cavity. Assessing patients and proposing effective and comprehensive pain management that minimizes opioid dependence risk while optimizing pain symptom relief is incumbent on providers, especially those who offer specialized professional care like dentists or those who are unable to provide a definitive diagnosis and treat the etiology of pain such as ED providers or nurse practitioners. Almost a quarter of opioid prescriptions (23.4%) were provided for an outpatient dental diagnosis in the Medicaid population evaluated between 2013 and 2015. Earlier studies assessing prescribing rates for opioid medications for NTDCs have shown steadily increasing rates, from 38% in 1997–2000, to 45% in 2003–200724, to 50.3% between 2007 and 201018. According to NAMCS data, half (49.7%) of opioid prescriptions were related to dental/jaw pain of ED discharges from 2006–10. Our study findings are somewhat lower (38.4% for EDs) and this may be attributed to differences in study design and data source. Our study cohort is derived from all ages and only outpatient dental claims.

We found that women were 50% more likely to fill an opioid prescription for any dental diagnosis than men. This may be attributable to a higher nociception and lower pain tolerance threshold among women when compared to men20. Findings from an earlier study suggested that women might be 10% more likely to receive an opioid for dental pain management in an ED, but this was found to be non-significant23. Our findings are consistent with other studies that report, regardless of the diagnosis, women (38.8%) were more likely to be prescribed an opioid than men (33.9%)19. The magnitude of race and ethnic disparities were similar to those found by gender. Opioid prescriptions rates for any dental diagnosis were nearly three times higher for African-American and Whites than for Hispanic females. White males filled slightly more opioid medications than African-American males (12%) in our study.

The racial disparities found in this study can be compared to results from two additional studies that assessed dental related conditions. A study utilizing NAMACS data25 that evaluated emergency department visits for tooth pain showed that African-Americans were nearly two times less likely to get an opioid prescription in the ED. It must be noted that the study population included Medicare, Medicaid, privately insurance and uninsured patients, and so the disparity noted was slightly higher than our Medicaid-only study findings. Another study that examined emergency department utilization for NTDCs found no observable difference for opioid prescriptions when stratified by race18. The disparities, and the associated variation noted between them, are due both to a different study population and a different reason for the initial emergency department visit.

Racial disparities in emergency department pain management for various types of postoperative, nonmalignant, chronic and malignant pain have been well described for acute medical and surgical issues17, 26–30. Our findings reiterate racial and gender disparities in prescription provision that are echoed in medical diagnoses. In medicine, these differences have been attributed to various factors, including the suggestion that provider’s own unconscious biases and cultural differences between provider and patient have an influence14. In a study31 that controlled for several factors while investigating the effects of patient race and gender on provider prescribing patterns, male physicians provide more pain relief to white patients and female physicians provided more pain relief to African-American patients. Another study reported that African-Americans are less likely to receive an opioid prescription compared to white patients by medical providers for noncancer pain32. In our study, African Americans were less likely to receive an opioid following a dental diagnosis compared to Non-Hispanic whites when the provider source was a medical specialist or the ED. However, when the opioid was prescribed following a dental diagnosis from a dentist or nurse practitioner, African Americans were more likely to receive an opioid. Additionally, African American and Non-Hispanic white patients were more likely to receive an opioid following a dental diagnosis compared to Hispanics regardless of provider source.

It appears that pain management for dental conditions is not consistent across various health care providers for some patient groups and these treatment differences may be an indication of the many complexities involved in pain perception, presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Findings from our study indicate that nurse practitioners prescribed an opioid following a dental diagnosis for about 1 in every 4 Medicaid patients. In a 2006 NAMCS study, nurse practitioners were prescribing opioids two times more often than dentists, but at lower rate than ED providers36. Interestingly, this suggests that nurse practitioners follow similar prescribing patterns as dentists when stratifying by various race/ethnicity characteristics of patients.

Our study shows that ED providers prescribe more opioid prescriptions than any other provider type. With multiple provider sources, differing levels of patient complaint severity and varied levels of care offered, dentists are still prescribing fewer opioid medications than other provider sources. It has been reported that upwards of half of opioid prescriptions are provided for NTDC33, but these rates have not been compared to other providers sources or treatment modalities. One study analyzing only pharmacy data reported that dentists, unlike their primary care physician (28.8%), internist (14.6%) and orthopedic (7.7%) colleagues, only prescribed opioid medication 8% of the time34. This is consistent with the results of our study that showed 10.8% patients received an opioid following a dental diagnosis by a dentist. This observed rate is also consistent with the overall national rate where approximately 12% of opioids are prescribed by dentists4, 35. In fact, the contribution by dentists to the overall national rate of opioid prescriptions in the US is the lowest when compared to other provider sources in our study. Dentistry was third in opioid prescription rates among commercial claims in North Carolina32.

A promising intervention demonstrated that changing prescribing guidelines for ED providers was associated with a reduction in both the rate of opioid prescriptions provided and the total number of visits to the ED for patients who presented with dental pain37. However, it was not clear whether these guidelines addressed the underlying racial or ethnic disparities observed in other studies. One area that can benefit from additional research is the evaluation of pre-doctoral educational curriculum and professional continuing educational efforts that focus on improving pain management while reducing disparities in receipt pain medications (e.g., opioids) among underserved groups.

Although we found differences in receipt of opioids for dental diagnoses by gender and race/ethnicity overall, this difference is not affected by the type of dental diagnosis received (see Figure1 & 2). Interestingly, differences between ED providers and dentists in the proportion of opioid prescriptions provided based on dental diagnoses was significant. This suggests that ED providers and Dentists may record dental diagnoses (ICD -9 CM codes) differently. For example, ED providers may rely more on the symptoms and visual presentation of the dental condition rather than the actual etiology of the dental event. This raises important considerations for future health services research, especially as medical and dental health records become more integrated.

Because our study was limited to a Medicaid cohort, our findings are not generalizable to the US population. Thus, additional work should be done in to identify similar race/ethnic differences in a commercially insured population. The Truven database does not contain patient-level pharmacy drug dosage data, so we were unable to definitively quantify the amount of opioids prescribed for each individual and express those amounts in morphine milligram equivalents. Finally, we had many unknown provider sources, which may contribute non-systematic error to our analyses. Although there are some limitations to our study, strength of our study is the large number of contemporaneous claims from a population that typically underutilizes the dental health care system. Finally, our study reports on differences observed among race/ethnic and provider sources in receipt of opioid prescriptions for dental diagnoses among the Medicaid population.

Conclusion

There are significant differences in receipt of an opioid following a dental diagnosis based on patients’ race/ethnicity and gender in the Medicaid population. There are also differences in the prescribing patterns of dentists and ED providers as well. Non-Hispanic white and African-American women are more likely to receive an opioid following a dental diagnosis than any other group. The contribution by dentists to the overall opioid prescriptions provided is 10.8% and is the least among all provider sources examined. Although race/ethnic or gender differences for receipt of an opioid are not influenced by the type of dental diagnoses, there were differences by dental diagnostic types and receipt of opioids between ED providers and dentists.

Implications for Dental Practice

Overall, dentists are substantially providing less opioid prescriptions compared to their medical colleagues for pain treatment following a dental diagnosis in the Medicaid population we examined. When considering pain management for dental and oral health related conditions, dentists should continue to implement conservative prescribing practices as recommended.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the generous support of the DentaQuest Institute for providing support to obtain the data and to assist in data management and analytical activities.

Funding Body Agreements & Policy: This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Library of Medicine (NLM) and Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications (LHNCBC). Some authors were paid a salary by the NIH.

Abbreviations

- MMEs

Morphine Milligram Equivalents

- NIH

National Institutes of Health, ICD-9-CM

- CI

Confidence intervals

- ED

Emergency Department

- NAMCS

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- NTDCs

nontraumatic dental conditions

- ICD-10 CM

International Classification of Disease Tenth edition Clinical Modification

- ICD-9 CM

International Classification of Disease Ninth edition Clinical Modification

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contribution of authors:

Chandrashekar Janakiram made substantial contributions to the concept, design, drafting & review of the manuscript, and conducting the data analyses.

Natalia I. Chalmers made substantial contributions to the concept, design, and drafting of the manuscript.

Paul Fontelo made substantial contributions to the concept, design, drafting and review of the manuscript.

Vojtech Huser contributed the concept, design, drafting and review of the manuscript

Gabriela Lopez Mitnik contributed to the data analysis and review of the manuscript.

Avery R. Brow contributed the design, drafting and review of the manuscript.

Timothy J. Iafolla contributed the design, drafting and review of the manuscript.

Bruce A. Dye made substantial contributions to the concept, design, drafting and review of the manuscript; and provided supervision of the project.

Ethics Statement: The current study was determined exempt from review by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board. The authors do not have any financial or other competing interests to declare.

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Contributor Information

Chandrashekar Janakiram, National Library of Medicine/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 31 Center Drive, Suite 4B62, Bethesda, MD 20892-2190.

Natalia I. Chalmers, Director, Analytics and Publication, DentaQuest Institute, 10320 Little Patuxent Pkwy., Suite 214, Columbia, MD 21044.

Paul Fontelo, National Library of Medicine/National Institute of Health, 8500 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20894.

Vojtech Huser, National Library of Medicine/National Institute of Health, 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20894.

Gabriela Lopez Mitnik, Statistician, National Institute of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 31 Center Drive, Suite 4B62, Bethesda, MD 20894.

Timothy J. Iafolla, Chief, Program Analysis and Reports Branch, National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 31 Center Drive, Bethesda, MD 20892-2190.

Avery R. Brow, Project Manager, Analytics and Publication, DentaQuest Institute, 10320 Little Patuxent Pkwy., Suite 218, Columbia, MD 21044.

Bruce A. Dye, Dental Epidemiology Officer, National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 31 Center Drive, Suite 5B55, Bethesda, MD 20892-2190.

References

- 1.Gostin LO, Hodge JG, Jr, Noe SA. Reframing the opioid epidemic as a national emergency. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1539–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000–2010. Med Care. 2013;51(10):870–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95d86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringwalt C, Gugelmann H, Garrettson M, et al. Differential Prescribing of Opioid Analgesics According to Physician Specialty for Medicaid Patients with Chronic Noncancer Pain Diagnoses. Pain Research and Management. 2014;19(4) doi: 10.1155/2014/857952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pon DAK, Curi D, Okyere E, Stern CS. Combating an Epidemic of Prescription Opioid Abuse. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2015;43(11):673–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dionne RA, Gordon SM, Moore PA. Prescribing opioid analgesics for acute dental pain: time to change clinical practices in response to evidence and misperceptions. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2016;37(6):372–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okunseri C, Dionne RA, Gordon SM, Okunseri E, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid analgesics for nontraumatic dental conditions in emergency departments. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;156:261–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox TR, Li J, Stevens S, Tippie T. A performance improvement prescribing guideline reduces opioid prescriptions for emergency department dental pain patients. Annals of emergency medicine. 2013;62(3):237–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grover CA, Elder JW, Close RJ, Curry SM. How frequently are “classic” drug-seeking behaviors used by drug-seeking patients in the emergency department? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;13(5):416. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2012.4.11600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HH, Lewis CW, Saltzman B, Starks H. Visiting the emergency department for dental problems: trends in utilization, 2001 to 2008. American journal of public health. 2012;102(11):e77–e83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wall TP, Vujicic M, Nasseh K. Recent trends in the utilization of dental care in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(8):1020–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renton T. Dental (odontogenic) pain. Reviews in pain. 2011;5(1):2–7. doi: 10.1177/204946371100500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalmers N, Grover J, Compton R. After medicaid expansion in Kentucky, use of hospital emergency departments for dental conditions increased. Health Affairs. 2016;35(12):2268–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heins A, Homel P, Safdar B, Todd K. Physician race/ethnicity predicts successful emergency department analgesia. The Journal of Pain. 2010;11(7):692–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgess DJ, Van Ryn M, Crowley-Matoka M, Malat J. Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: insights from dual process models of stereotyping. Pain Medicine. 2006;7(2):119–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rupp T, Delaney KA. Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine. Annals of emergency medicine. 2004;43(4):494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahim-Williams B, Riley J, Herrera D, et al. (906): Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. The Journal of Pain. 2006;7(4):S76. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todd KH, Funk KG, Funk JP, Bonacci R. Clinical significance of reported changes in pain severity. Annals of emergency medicine. 1996;27(4):485–89. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Xiang Q, Thorpe JM, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid and nonopioid analgesics for dental care in emergency departments: Findings from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(4):283–92. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prevention CfDCa. Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes. United States: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aufiero M, Stankewicz H, Quazi S, Jacoby J, Stoltzfus J. Pain Perception in Latino vs. Caucasian and Male vs. Female Patients: Is There Really a Difference? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;18(4):737. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.1.32723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. Journal of general internal medicine. 2013;28(11):1504–10. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Cydulka RK, Wigton RS, Baker DW. Variability in emergency physician decisionmaking about prescribing opioid analgesics. Annals of emergency medicine. 2004;43(4):483–93. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Thorpe JM, Xiang Q, Szabo A. Patient characteristics and trends in nontraumatic dental condition visits to emergency departments in the United States. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dentistry. 2012;4:1. doi: 10.2147/CCIDEN.S28168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Thorpe JM, Xiang Q, Szabo A. Patient characteristics and trends in nontraumatic dental condition visits to emergency departments in the United States. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2012;4:1–7. doi: 10.2147/CCIDEN.S28168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H, Lewis C, McKinney C. Disparities in Emergency Department Pain Treatment for Toothache. JDR Clinical & Translational Research. 2016;1(3):226–33. doi: 10.1177/2380084416655745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah AA, Zogg CK, Zafar SN, et al. Analgesic access for acute abdominal pain in the emergency department among racial/ethnic minority patients: a nationwide examination. Medical care. 2015;53(12):1000–09. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston V, Bao Y. Race/ethnicity-related and payer-related disparities in the timeliness of emergency care in US emergency departments. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2011;22(2):606–20. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA pediatrics. 2015;169(11):996–1002. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mills AM, Shofer FS, Boulis AK, Holena DN, Abbuhl SB. Racial disparity in analgesic treatment for ED patients with abdominal or back pain. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2011;29(7):752–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanderah TW, Ossipov MH, Lai J, Malan PT, Jr, Porreca F. Mechanisms of opioid induced pain and antinociceptive tolerance: descending facilitation and spinal dynorphin. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisse CSSP, Sanders KN, Syat BL. Do gender and race affect decisions about pain management? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:2111–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016004211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ringwalt C, Roberts AW, Gugelmann H, Skinner AC. Racial disparities across provider specialties in opioid prescriptions dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic noncancer pain. Pain Medicine. 2015;16(4):633–40. doi: 10.1111/pme.12555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Thorpe JM, Xiang Q, Szabo A. Medications prescribed in emergency departments for nontraumatic dental condition visits in the United States. Medical care. 2012;50(6):508. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. Jama. 2011;305(13):1299–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute THC. The Role of Dentists in Prevention Opioid Abuse. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cipher DJHR, Guerra P. Prescribing trends by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the United States. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18(6):291–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox TR, Li J, Stevens S, Tippie T. A performance improvement prescribing guideline reduces opioid prescriptions for emergency department dental pain patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(3):237–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]