Abstract

A wider discussion is taking place nationally regarding how universities can make ‘real’ change in the old way of academic business. These changes include a hard look at the inclusive nature of the institutional environment as a whole. Lack of diversity is most noticeable within higher administrative levels of universities across the country. We have now reached a point where true reflection and assessment of inclusive practices on our campuses must be carried out so that we fully serve the needs of all of our students. In this breakout session participants will share best practices currently in place or strategic planning at your institutions, which not only promote diversity and inclusion in the classroom but describe strategies for institutional buy-in at all levels and provide examples of accountability measures that further promote diversity and inclusion at higher administrative levels.

Keywords: diversity, inclusion, administration, implicit bias, best practices

Overview of the Problem

“Research has shown that diverse groups are more effective at problem solving than homogeneous groups, and policies that promote diversity and inclusion will enhance our ability to draw from the broadest possible pool of talent, solve our toughest challenges, maximize employee engagement and innovation, and lead by example by setting a high standard for providing access to opportunity to all segments of our society.”

- President Obama, October 5, 2016

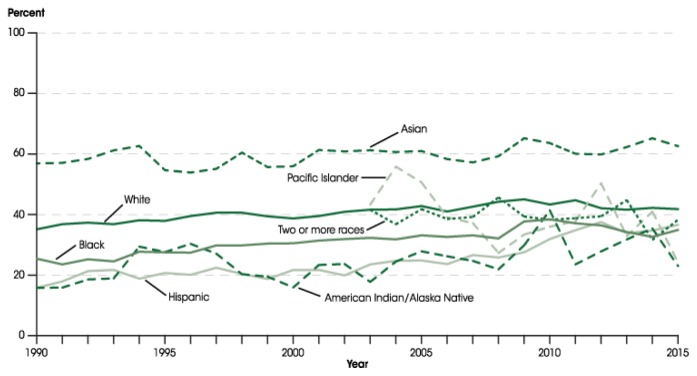

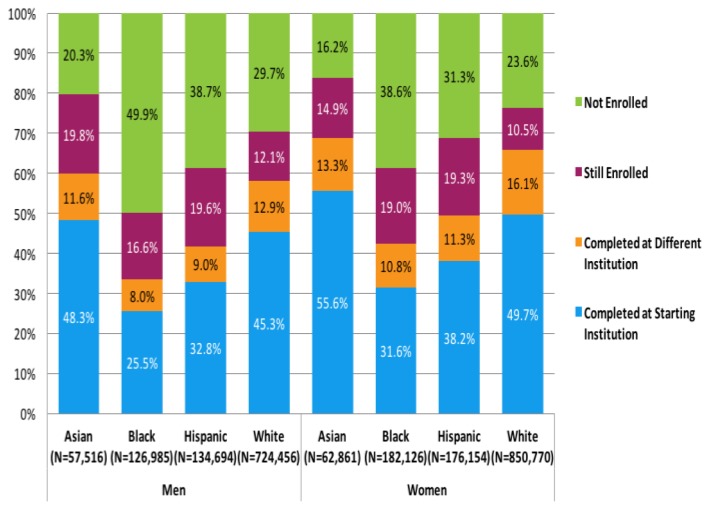

More than 40 years of diversity initiatives have resulted in a notable increase in the number of underrepresented minority students attending colleges and universities across the nation (Li, 2007; Snyder et al., 2016; McFarland et al., 2017). According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, from 1995–2015, the number of African American college students rose from 27.5 to 35 percent and the number of Hispanic students rose from 21 to 37 percent (Snyder et al., 2016; Fig. 1). While this increase in diversity at the student level is commendable, the completion rates among different racial and ethnic groups differs by as much as 20 percentage points, with African American males lagging behind all groups compared (Shapiro et al., 2017; Fig. 2). Still more striking is the representation of diversity in STEM majors. Of the URM students entering as first-time college students, 33% are interested in STEM fields (Kena et al., 2015), again highlighting the success of previous diversity initiatives whose focus was to increase the number of diverse individuals with undergraduate degrees. Despite these efforts, several challenges remain, the most concerning is the dramatic drop in the number of URMs who go on to pursue graduate degrees, especially in STEM fields (Kena et al., 2015; Snyder et al., 2016; McFarland et al., 2017; NSF 17-306, 2017). Initial attempts at characterizing the cause of these losses suggested that the URM student perhaps was not equipped or was poorly prepared for graduate or professional work (Treisman, 1992; Schuman et al., 1997). Thus, began renewed efforts to support the URM student with programs which focused on ‘fixing’ the student so that they might be retained and ultimately successful (Anaya and Cole, 2001; NIH 2007; Hurtado et al., 2009). The characterization of the URM student as lacking persistence or needing to be coached on resilience, did not make sense given the fact that many of these students have already overcome significant challenges to access higher education (Hurtado et al., 2009; Byars-Winston et al., 2016). The alternative hypothesis then would be one that instead questions the environment of academia. The main question being, have we truly made efforts to become more inclusive of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds so that we capitalize on the natural resilience of the URM student by acknowledging and celebrating that they have already achieved so much, and now we will provide the service that they need to be ultimately successful in their chosen careers.

Figure 1.

Total college enrollment rates of 18–24-year-olds in degree-granting institutions, by race/ethnicity: 1990–2015. SOURCE: U. S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS), October 1990–2015. See Digest of Education Statistics 2016. Table 302.60.

Figure 2.

Overall college completion rates based on Race, Ethnicity, and Gender. A larger proportion of black students (44.6%) were not enrolled at the end of the study period (had no degree or certificate and no enrollment record in the sixth year), compared to Hispanic (35.0%), white (26.9%), and Asian (20% students. In terms of gender differences, female students graduated at higher rates than male students and were less likely to drop out, regardless of race and ethnicity (Tate, 2017).

The 2017 Faculty for Undergraduate Neuroscience (FUN) workshop at Dominican University focused on inclusivity in training and teaching the next generation of neuroscientists. The workshop brought together faculty, administrators, and program directors to discuss diversity and inclusion, particularly in the Neurosciences and other STEM fields. These discussions started first by defining the terms diversity and inclusion. Diversity describes a quantifiable measure of individuals (Williams et al., 2005; Puritty et al., 2017; Fradella, 2018,), such as the number of left-handed individuals in a group or the demographics of the undergraduate student population. Inclusivity, on the other hand, is not quantifiable. It is a feeling. It is a belief that one’s experiences and training are respected by those around you and that your participation provides unique perspectives that help create better solutions (Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Clark et al., 2016; Fradella, 2018). Thus, while we have seen increased diversity in our campus populations, it is evident from Figure 2 that inclusion is not a given. To be truly inclusive the institutional environment must change to encourage diverse populations to thrive and to promote a sense of belonging (Williams et al.,2005; Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Hurtado et al., 2017; Puritty et al., 2017). True institutional reform will involve buy-in at ALL levels. In this paper, we are not suggesting a prescription, as every institution is unique in the challenges they hold. We instead highlight suggestions and best practices that address inclusivity at the institutional level, which are the most promising of change. Our hope is that university leaders reading this article find tools that can be implemented across the institution and that collectively we move beyond the discussion-level of diversity and inclusion to a place where we are actively changing the landscape.

Importance of leadership’s role in changing the institutional environment

Strategies that promote inclusivity must happen at all levels of the academic ecosystem (Fig. 3) – student; faculty; alumni; and staff, particularly administrative levels. Each component of the academic ecosystem must be engaged in the larger discussion on diversity and inclusion, with cross communication between them. To be most effective, the selection process for each member of the ecosystem also necessitates inclusion. When a student or an employee is selected from a pool of applicants, each has been through a lengthy evaluation process, culminating with the institution making a commitment to them as members of the institutional family. Thus, a strong message of support must be sent from the highest levels of administrative leadership that both diversity and inclusion are an integral part of the institution’s mission or strategic plan. Some examples of how the university can demonstrate support for these initiatives include proactively seeking support for students, faculty or staff before they arrive on campus. At the student level, the support needed would be informed by communication from admissions, enrollment, and/or financial aid about specific incoming challenges faced by the student cohort. The prospective employee can engage with the Diversity/Inclusion Office during the interview process to bring up any questions related to culture and environment at the institution and surrounding area. Upon hire, employees should be informed about the ombudsman process via Human Resources or the Diversity and Inclusion office in case problems arise with the department, administrators, or students. Advocating for diversity and inclusion beginning at the student or faculty level will not be supported if there isn’t backing by the administration that this initiative is essential to the positive growth of the institution. Many universities that have traditionally struggled with diversity, now have chartered diversity and inclusion strategic plans or mission statements, including Pomona College; Princeton University; Davidson College; Texas A&M University, to name a few. These types of discussions can be met with fear but starting with low-risk activities like the development of a task force on diversity and inclusion or having a community forum can help begin the conversation in a non-threatening way (Takayama et al., 2017; personal communication R. Burks – Southwestern University). Perhaps key to these first discussions is the acknowledgement that diversity and inclusion bring together perspectives of multiple experiences that in the end help come to a better solution. Many of our chosen fields of study, especially in STEM, thrive on the perspectives of diverse individuals (Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Puritty et al., 2017; Fradella, 2018). Administrators must also acknowledge elements of the status quo that need to change in order to gain faculty and student trust. If faculty believe that their opinion and the opinion of others is valued by the institution and bring value to the process, the walls that were once raised against change will be removed. Many universities have also incorporated a new leadership position, the Chief Diversity Officer, as a part of the administrative team. While some may suggest that the hiring of a diversity officer may take away from the responsibility of the institution President to lead the charge on providing a more diverse academic climate (Frum, 2016), a diversity officer may serve as a measure of accountability. Administrators can hire trained facilitators and engage faculty whose scholarly work is in this area to lead departmental diversity and inclusion focus groups where data can be shared and discussed that demonstrates that while we’ve made progress providing access to more diverse individuals to higher learning, they are not retained far beyond the master’s level of learning (Kena et al., 2015; Sowell, 2015; NSF 2017). In a department this discussion might result in the setting of goals that prioritize a holistic approach to working with students so that they are retained and not simply focusing on the student as the problem (Clark et al., 2016; Maton et al., 2016).

Figure 3.

The academic ecosystem is comprised of administrators, staff, faculty, students, and external partners. In order to promote diversity and inclusion, all members within each component of the academic ecosystem must communicate. These conversations should be constant, dynamic, and will likely involve multiple components simultaneously.

The goal of increased diversity is not enough

What is your mission? Are you accomplishing what you have stated as your guiding principles? Most universities have as a part of their mission statement “to provide an environment that inspires learning from all perspectives.” How diverse are your classrooms and faculty? Do the administrators, students, staff, and faculty exhibit a variety of backgrounds and experiences? Do you know what these experiences are? Is there equity in perspectives or is a sole viewpoint represented? What students participate in high impact experiences such as summer research and study abroad? The answer to these questions provides important guidance as an institution begins the journey to provide more inclusive environments. These questions provide an initial climate assessment that focuses on the psychosocial, environmental, and emotional, instead of focusing solely on retention (aka the numbers). Assessment begins with the institutional community coming together to ask hard questions regarding environment. This level of assessment necessitates open dialogue about race, cultural competency, and bias – both implicit and explicit (Williams et al., 2005; Diaz and Kirmmse, 2013; Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Stanley, 2016; McFarland et al., 2017). Assessment must not only be internal (i.e., listening to the voices within the institution), but also external. If we only listen to the voices of our siloed and sometimes shortsighted communities, we may miss something because we are used to the status quo and may not be aware of what equity looks like. Universities have increased access to education for all people, as measured by the steady rise in the number of URM students on campuses, but this is not enough. We have effectively supplied the keys to the castle without acknowledging that the castle has a history and infrastructure that prohibits all who enter from thriving equally. Diversity in a non-inclusive environment is not authentic and will fade. To prevent this, administrators and departments could start by setting goals with specific outcomes that demonstrate diversity and inclusion is a priority and provide mentorship to faculty, staff, and students on how to develop a more inclusive environment. Recently, Wake Forest College asked each department to develop a diversity and equity action plan that was unique to its discipline, students, faculty, staff, alumni, curriculum and programs. These plans include an analysis of department-specific opportunities and challenges, metrics to measure success of the plan, and are revisited annually (Undergraduate College, (n.d.); Office of Diversity and Inclusion Wake Forest Univ., 2015). Equally important are the goals set by the institution with a strategic plan/institutional forecast that has as a core value to develop diversity and inclusion initiatives campus-wide.

We must talk about race

We must acknowledge that we all struggle with biases. Thus, to truly change the environment of academia, we must acknowledge that it has existed for many years predominantly as a culture of white men who came from privilege (Schuman et al., 1997; Williams et al., 2005; Whittaker et al., 2015; Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Puritty et al., 2017). With the number of diverse individuals attending college now, we must offer an environment that is culturally relevant; an environment that is better at listening across cultures. We must offer an environment that acknowledges differences, values them, and as a result, seeks relationships with individuals that have lived different experiences than their own (Asai and Bauerle, 2016). The recruitment and retention of diverse students; faculty; administration; and staff depends on the academic community accepting and respecting everyone’s experiences (Whittaker et al., 2015; Fradella, 2018; Stanley, 2016; U. S. Department of Education, 2016). It is a social imperative to host these discussions. These discussions should not be siloed to single departments, such as Anthropology and Sociology, but should be campus-wide. The administration can institute an annual retreat or on-campus conference where faculty and staff can examine diversity and inclusivity at the institution, reflect on the strategic plan to celebrate accomplishments and identify growth edges and persistent barriers, and make an action plan for the coming year. Administrators can also encourage departments to examine their curriculum and extracurricular activities. Funds can be earmarked for a campus-wide seminar series or a single high profile annual speaker addressing diversity and inclusivity. Likewise, the administrators can emphasize diversity and inclusivity as a value in discussions of teaching and learning that occur in faculty development arenas. As another example, STEM departments can talk about minority health disparities in clinical care and celebrate contributions from a variety of individuals to our current understanding in the field. A simple exercise in examining how diverse our seminar speakers are can be illuminating. Are we always inviting a single perspective as the authority on a topic? Do our invited speakers think about and acknowledge the inherent bias in their work? This is particularly important for those tackling research questions that are relevant to the biomedical sciences, where ignoring a variable like race might have dire consequences. We are no longer one note, we are instead, a collection of many notes that when recognized bring a perspective that raise the resolution of our understanding. Change is hard but not if it is a concerted effort. How can we then encourage change as a whole and take away the stigma of individual biases? Some suggestions for how to have these important discussions include hosting faculty retreats that have as their focus a very carefully lead discussion on implicit bias and microaggressions, so that we create an environment where biases are at the very least acknowledged (Robinson et al., 2016; Lucey et al., 2017). These conversations should not be entered into lightly. The institution should invest in facilitators that are trained to engage groups in an effective discussion of these topics (e.g., AACLU, PKAL, SACNAS, etc.), and a location that is free from territorial tension (i.e., not on campus). It is in this safe space that true dialogue can be had which ultimately demonstrates the benefits of having diverse perspectives at the table (Williams et al., 2005; Whittaker et al., 2015; Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Hurtado et al., 2017).

Curricular changes

While the scope of this article will not include changes that individual faculty can make in their courses, the curricular level is one of the more approachable levels at the institution in which inclusivity can first be addressed. Overall, discussions regarding curriculum often make assumptions about what students know (Treisman, 1992; Anaya and Cole, 2001; Robinson et al., 2016). Perhaps to address inclusion at the institution, one might ask the faculty to take a step back and reevaluate the assumptions being made regarding the student population and how a simple adjustment in how we perceive the student, may inspire a more inclusive environment (Anaya and Cole, 2001; Robinson et al., 2016; Gooblar, 2017). With so few URM students in our midst, we should know them by name and form genuine relationships so that we can serve as their advocates and promote a holistic approach to their education. For example, if a student is an athlete, faculty and coaches can communicate schedules at the beginning of the semester so that both sides are aware when there are busy times in their respective areas (e.g., first exam, away game or tournament). Likewise, financial aid and admission officers know potential challenges that these students may face (e.g., needing to work during the academic year) and can share this information with faculty (Boland et al., 2017). Administrators can help by making structures that support student success. For example, using work study jobs to support student research in the laboratory so that students are working toward their future career path rather than spending hours as a cafeteria worker. Furthermore, many introductory courses that host large numbers of first year/sophomore students starting out in STEM majors are designed as “weed out” courses (Tyson and Spalding, 2010; National Academy of Science, 2011). Could we instead have different entry points into the program that would foster success instead of “weeding out”? For example, do Biology and Chemistry have to be taken together in the first year for the student to graduate with a particular STEM degree or to be able to progress to a certain scientific career upon graduation? Can a structure be created where money is made available for students that demonstrate high academic achievement in the first year to take Chemistry in the summer so that they stay on track? Or can the end goal still be accomplished if a student waits until sophomore year to start Chemistry? Smaller class sizes, fostering creativity and intellectual curiosity in the classroom rather than marching through a textbook, creating more opportunities for student collaborations are all ways to achieve these goals and are particularly effective for URM students (Hurtado et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2013). While there are many strategies that individual faculty can use to improve the inclusive environment of the classroom (Haak et al., 2011; Tanner, 2013; Gooblar, 2018; Supiano, 2018;), it is important for administrators and departments to reflect on how programs are structured and if the sequence of classes and assessments would possibly exclude a population of student from being successful or if the sequence of classes and pre-requisites makes strong assumptions that ignore the challenges faced by underrepresented groups. Administrators should encourage and support relationships between STEM departments and the Office of Institutional Research to determine trends in high enrollment introductory level science courses, correlating academic performance to student demographics (e.g., race, gender, first generation and socioeconomic status, high school performance, etc.) so that they can develop multiple tracts through the major.

New approaches to the hiring and promotion process

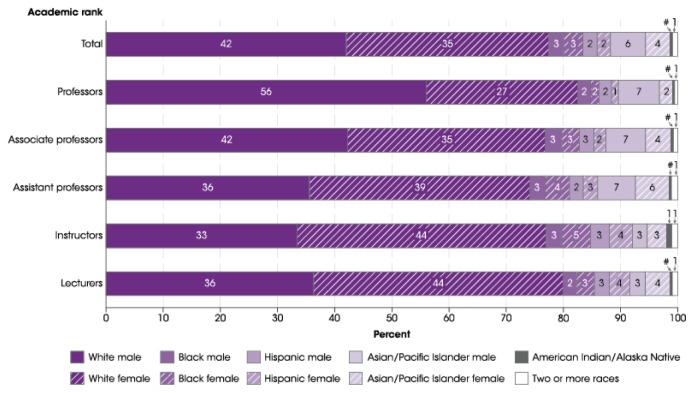

While diversity of the student population has been raised at the institution, diversity is not sustained at the faculty level (Fig. 4; Kena et al., 2015) and is almost non-existent at the administrative level. In fall 2015, of all full-time faculty at degree-granting postsecondary institutions, 77 percent were white, 10 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander, 6 percent were Black, and 4 percent were Hispanic. American Indian/Alaska native individuals or individuals of two or more races made up 1 percent or less of the full-time faculty. Thus, to address diversity and inclusion at the institutional level, it will be important to address the dearth of URM faculty and administrators at the institution. External partners of the institution such as alumni and trustees should champion diversity and inclusion initiatives across campus, especially those that affect the hiring and promotion processes. It is in the institutions’ best interest for these outside agencies to reflect the diverse voices they wish to elevate via representation within these groups. To enhance and encourage diversification of the applicant pool, position advertisements can include an explicit statement of the institution’s goal of hiring and sustaining a diverse work force that fosters an inclusive environment for learning across cultures (Johnson, 2016; Fradella, 2018).

Figure 4.

Percentage distribution of full-time faculty in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by academic rank, race/ethnicity, and sex. (Kena et al., 2015).

Administrations and departments interested in encouraging diverse populations to apply can reach out to Diversity Training Programs like BRAINS (Broadening the Representation of Academic Investigators in NeuroScience), SPINES (Summer Program in Neuroscience, Excellence, and Success), SACNAS (Society for the Advancement of the Chicano and Native American Scientists), NHSN (National Hispanic Science Network), or SREB (Southern Regional Education Board). These national training programs provide support for the underrepresented faculty member as they enter the academic workforce and thus are an invaluable resource for search committees (Margherio et al., 2016). Hiring guidelines will also likely require revision. Many universities have become more conscientious about the make-up of the hiring committee, putting together a diverse set of cultural and gender perspectives at the table (Williams et al., 2005; Whittaker et al., 2015; Johnson, 2016; Fradella, 2018). Moreover, an administrator or diversity officer can serve as a committee member who is trained to be more aware of biases that arise during the hiring process and thus work to minimize them so that the best candidates are invited to campus or that a meritable candidate was not overlooked (Frum, 2016; Fradella, 2018).

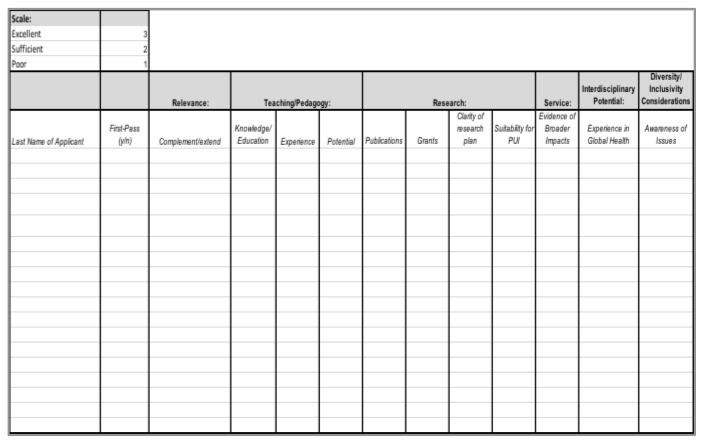

Administrators can urge departments to develop and use a hiring rubric before the position is released for advertisement so that there is collective agreement on what the committee should judge as criteria for a candidate that makes it to an on-campus interview (Fradella, 2018). These rubrics work best when they also include a criterion for judgement of an inclusivity statement that is provided by the candidate as a part of the application package (Fig. 5; shared by J. King, 2018). Inclusivity statements as a part of the application or as a part of the interview process highlight the institutional commitment to providing an inclusive environment that fosters diverse perspectives (Utz, 2017; Fradella, 2018). These statements are becoming more standard as a component of the hiring process thus, it has also been suggested that training on diversity and inclusion begin at the graduate or post-doctoral level so that job candidates understand that inclusion is as essential to a successful job candidate as is their research or teaching philosophy. Universities that have significantly addressed diversity and inclusion on their campuses, have also benefited from the voice of students, at the junior or senior level, who have served as a part of the hiring committee to provide input especially regarding the candidate’s ability to convey their level of comfort in creating and supporting an inclusive environment. Overall, these hiring strategies provide mechanisms universities may use to help address the need for building a more diverse faculty. It is also important to remember that diverse faculty must then be retained (Whittaker et al., 2015) and mentored to promotion, leadership, and administration. The wider discussion of inclusive excellence across the academy is one that suggests the need to change the landscape; to change the status-quo (Asia and Bauerle, 2016). We began our own discussion with data to suggest that although the number of diverse faculty (i.e., diversity) has increased, it is still not a true reflection of the diversity we see in society. When we look beyond assistant professor level, the percentage of underrepresented minorities that are retained through Full Professor drops dramatically (Fig. 4; Kena et al., 2015). The natural questions that arise, are “why then are diverse faculty not retained? And why are those that remain not seen in administrative positions?” (i.e., what are the barriers to progress?). One can imagine an approach to address these questions may be no different than how we address the needs of our plants. At a recent university discussion on diversity, Dr. Beronda Montgomery presented an analogy with how we care for our plants (Montgomery, 2017). If the plant does not fare well, our immediate reaction is to question the environment – is the soil pH appropriate? has too much or too little water been given for it to grow? are the proper nutrients available in the soil or are supplements needed? It is not typical to assume that anything is wrong with the plant itself, yet this has been the assumption made regarding the retention of underrepresented students, faculty, and staff within the institution (Montgomery, 2017). If we are to make genuine change within the traditional culture of the academy, then we must shift the blame of preparedness from the individual to the institution and approach as we do our plant-life, begin by assessing the environment, looking for clues that may offer suggestions for change (Williams et al., 2005; Whittaker et al., 2015; Stanley, 2016; Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Montgomery, 2017 Puritty et al., 2017; Fradella, 2018).

Figure 5.

Example rubric for hiring committee use.

Measure your progress – The ‘A’ Words, Assessment and Accountability

As academics we understand that programmatic or curricular changes warrant periodic assessment, if for nothing else to be certain that we haven’t lost focus on our institutional and departmental goals. Our approach to changes that address inclusion should be no different. The curriculum is a logical, non-threatening, place to begin assessment because, if found lacking, one can be mentored on how to incorporate inclusive strategies or pedagogy in their course structure. Some of the nation’s leading undergraduate institutions are at the frontier of these strategies and their faculty describe how they have provided an inclusive environment in the classroom as a portion of the student evaluation, annual faculty inventory, or the tenure and promotion process (Friedersdorf, 2016; Jaschik, 2016). Administrators at these institutions ask faculty to submit inclusivity statements describing efforts to provide students with inclusive learning environments. These changes have been met with some challenges and fears that warrant address as an institutional community. In any evaluative process, additional criteria that cause stress or anxiety for faculty warrant much discussion among the faculty and faculty governance before any significant changes are made to the faculty handbook. Use of a trial evaluation period with no penalty has been successful because it allows time for faculty to see that many are already hosting inclusive environments in their classroom and, thus, the fear of being assessed on inclusivity is lessened (Roll, 2017). In time, inclusivity becomes second nature just like any aspect of our responsibilities as faculty (Hockings, 2010; Lawrie et al., 2017; Gannon, 2018), such as scholarship and service. Mid-term evaluations are another low-stakes means of feedback that allow faculty, staff, and administrators to address concerns in real time/more quickly. Students can be asked to give examples of times they have or have not felt included in the classroom (Quaye and Harper, 2007), residence hall, common areas, etc. Assessment of inclusivity calls faculty, staff, and administrators to work together to define what this would look like at every level of the institution. Once an institutional-wide definition of inclusivity is accepted then faculty are better able to answer the question, “What does inclusivity mean for me and what I offer in the classroom or a meeting?” However, the assessment takes place, it is an essential piece to change what is promoted at the institution (Hurtado et al., 2008; Hurtado and Halualani, 2014; Asai and Bauerle, 2016; Hurtado et al., 2017; Foster-Frau, 2018). We must hold ourselves accountable to our goals, if we truly want to see change; this is especially true with the work of providing an inclusive environment at the institutional level. Buy-in could be encouraged via incentives that provide a gentler approach to the assessment. Some examples would be for administrators to incentivize by budget increases when a department increases their rating on inclusivity as judged by student evaluations and faculty/staff climate surveys (Smith and Powers, 2016). Many faculty annual reviews are already utilized to determine merit-based increases in annual salaries, with much discussion in faculty governance, this mechanism could then be an additional incentive. Lastly, as new programs that encourage inclusivity are developed, it is important to include external review from those institutions who have become “models” for diversity and inclusion (Hurtado and Halualani, 2014; Smith and Powers, 2016). While it is important to have internal review by administrators who are familiar with the institution’s history and practice, external review ensures that the assessment process is reduced of the bias that can permeate institutional memory. These assessments allow the institution to realistically determine, as a work in progress, if new practices are indeed going beyond increasing access to diverse populations to higher education to change behaviors within the institution that result in increased inclusion at all levels. This level of assessment demands that the institution sets realistic goals as steps are taken toward providing an inclusive environment. In short, it is important to acknowledge at every step, that this magnitude of change within the institutional environment, after many years of failing to address the need for an environmental shift within academia, will take time and cannot happen if the steps outlined above are not first discussed as a faculty, with administrative support.

Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) poised to serve as model institutions

Minority serving institutions have as a part of their history the institutional goal of providing access to higher education and graduating large percentages of URMs (Conrad and Gasman, 2015; Boland et al., 2017; NSF 2004; Hurtado et al., 2009; Hurtado et al., 2017). In 2013, MSIs served 40% of underrepresented students, totaling approximately 3.8 million students (Li, 2007; Boland et al., 2017). MSI’s contribution to the number of URM graduates in STEM are most noted at HBCUs (American Institutes for Research, 2012). In the biological and biomedical sciences alone, the top three HBCUs produced a large percentage of Black STEM PhD recipients at Howard (45%), Meharry Medical College (27%) and Morehouse School of Medicine (8%). MSIs also host a diverse faculty in comparison to non-MSI institutions, some with 20% of the faculty identifying as an underrepresented minority (Gasman and Conrad, 2015; Boland et al., 2017). There is a significant need to follow the contributions of MSIs to the larger discussion of diversity and inclusion. Because MSIs have served the underserved for many years, one might assume that they do not need to engage in discussions of diversity and inclusion. On the contrary, given their prize position, it is even more important for MSIs to address and take the lead on the development of a diverse and inclusive academy.

Concluding Thoughts

Though we know many of the pitfalls - lack of an actionable plan or measurable outcomes; institutional culture/status quo and resistance to change; changing reputation as an inhospitable environment or even as an institution lacking diversity (i.e., attracting people when you have none) - admittedly the best practices to increase diversity and inclusion in academic settings are scarce because we are on the frontier of truly beginning inclusive work at the institutional level. It is also important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to enhancing institutional diversity and inclusivity. Incremental progress and a focus on continual improvement will be required. Thus, this paper aims to provide a start to the conversation at your institution, if it has not started already, and to move the needle forward toward action and ultimately toward ensuring accountability for our actions.

In a perfect world, where educational/socio-economic disparities do not exist, what will our institutions look like from top to bottom? How do we move beyond simply providing access and instead provide a roadmap to a profession, where one is valued for the perspectives they bring to the table? If we change the landscape of the institution at the administrative level, will we see persistent diversity in STEM and the academy as a whole? What complex problems will we solve when we have a heterogeneous mix of voices, perspectives, and approaches at the table?

Footnotes

This work was supported by a UIW Faculty Endowment Research Award and a Feik School of Pharmacy Research Award to VG M-A. The authors thank Drs. Karen Parfitt and Barbara Lom for their intellectual contributions and discussions. We thank Associate Dean Kelly Sorensen at Ursinus College and Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculty at Elmhurst College for their thoughtful review and helpful comments to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- American Institute for Research. Broadening participation in STEM: A call to action. 2012. Retrieved on [25 May 2018] from https://www.air.org/resource/broadening-participation-stem-call-action.

- Anaya G, Cole DG. Latina/o Student Achievement: Exploring the influence of student-faculty interactions on college grades. J Coll Stud Dev. 2001;42:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Asai D, Bauerle C. From HHMI: doubling down on diversity. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(3) doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-01-0018. pii: fe6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland WC, Samayoa AC, Gasman M, Lockett AW, Jimenez C, Esmieu PL. National campaign on the return on investment of minority serving institutions. Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions; 2017. Retrieved on [22 May 2018] from https://cmsi.gse.upenn.edu/publications/research-reports. [Google Scholar]

- Byars-Winston A, Rogers J, Branchaw J, Pribbenow C, Hanke R, Pfund C. New measures assessing predictors of academic persistence for historically underrepresented racial/ethnic undergraduates in science. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(3) doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-01-0030. pii: ar32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Dyar C, Maung N, London B. Psychosocial pathways to STEM engagement among graduate students in the life sciences. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(3) doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-01-0036. pii: ar45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad C, Gasman M. Educating a diverse nation: lessons from minority serving institutions. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Kirmmse J. A new rubric for assessing institutional-wide diversity. Diversity and Democracy. 2013;16:3. https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/new-rubric-assessing-institution-wide-diversity. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Frau S. UTSA survey shows equity concerns among faculty, staff. San Antonio Express News. 2018. Retrieved on [25 March 2018] from https://www.expressnews.com/news/education/article/UTSA-survey-shows-equity-concerns-among-faculty-12730146.php.

- Fradella HF. Supporting strategies for equity, diversity, and inclusion in higher education faculty hiring. In: Gertz S, Huang B, Cyr L, editors. Diversity and inclusion in higher education and societal contexts. Palgrave Macmillan; Cham: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Friedersdorf C. When ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion’ are tenure requirements. The Atlantic. 2016. Retrieved on [24 May 2018] from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/06/when-diversity-and-inclusion-are-tenure-requirements/485057/

- Frum D. Whose interests do college diversity officers serve? The Atlantic. 2016. Retrieved [12 March 2018] from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/09/americas-college-diversity-officers/499022/

- Gannon K. The case for inclusive teaching. Chron High Educ. 2018. Retrieved on [24 May 2018] from https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Case-for-Inclusive/242636.

- Gooblar D. Yes, you have implicit biases, too. Chron High Educ. 2017. Retrieved [25 May 2018] from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Yes-You-Have-Implicit-Biases/241797.

- Gooblar D. Give students more options when they have to take your course. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2018. Retrieved [26 July 2018] from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Give-Students-More-Options/243416.

- Graham MJ, Frederick J, Byars-Winston A, Hunter AB, Handelsman J. Science education. Increasing persistence of college students in STEM. Science. 2013;341:1455–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.1240487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak DC, HilleRisLambers J, Pitre E, Freeman S. Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology. Science. 2011;332:1213–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1204820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockings C. Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: A synthesis of research. York: Higher Education Academy; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado S, Halualani R. Diversity assessment, accountability, and action: going beyond the numbers. Diversity and Democracy. 2014;17(4) Retrieved on [25 May 2018] from https://www.aacu.org/diversitydemocracy/2014/fall/hurtado-halualani. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado S, Griffin KA, Arellano L, Cuellar M. Assessing the value of climate assessments: progress and future directions. J Divers High Educ, Special Issue. 2008;1(4):204–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado S, Cabrera NL, Lin MH, Arellano L, Espinosa LL. Diversifying science: underrepresented student experiences in structured research programs. Res High Educ. 2009;50:189–214. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9114-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado S, White-Lewis D, Norris K. Advancing inclusive science and systemic change: the convergence of national aims and institutional goals in implementing and assessing biomedical science training. BMC Proceedings. 2017;11(Suppl 12):17. doi: 10.1186/s12919-017-0086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaschik S. Diversity as a tenure requirement. Inside Higher Ed. 2016. Retrieved on [24 May 2018] from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/05/23/pomona-moves-make-diversity-commitment-tenure-requirement.

- Johnson KR. How and why we built a majority-minority faculty. Chron Higher Educ. 2016. Retrieved on [18 January 2018] from https://www.chronicle.com/article/HowWhy-We-Built-a/237213.

- Kena G, Musu-Gillette L, Robinson J, Wang X, Rathbun A, Zhang J, Wilkinson-Flicker S, Barmer A, Dunlop Velez E. The condition of education 2015 (NCES 2015—144) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2015. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch. [Google Scholar]

- Lucey CR, Navarro R, King TE., Jr Lessons from an educational never event. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1415–1416. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie G, Marquis E, Fuller E, Newman T, Qui M, Nomikoudis M, Roelofs F, van Dam L. Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: a synthesis of recent literature. Teach Learn Inquiry. 2017;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Characteristics of minority-serving institutions and minority undergraduates enrolled in these Institutions (NCES 2008–156) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Margherio C, Horner-Devine MC, Mizumori SJY, Yen JW. Learning to thrive: building diverse scientist’s access to community and resources through the BRAINS program. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15 doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-01-0058. pii: ar49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Beason TS, Godsay S, Sto Domingo MR, Bailey TC, Sun S, Hrabowski FA., 3rd Outcomes and processes in the Meyerhoff Scholars Program: STEM PhD completion, sense of community, perceived program benefit, science identity, and research self-efficacy. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15 doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-01-0062. pii: ar48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland J, Hussar B, de Brey C, Snyder T, Wang X, Wilkinson-Flicker S, Gebrekristos S, Zhang J, Rathbun A, Barmer A, Bullock Mann F, Hinz S. The condition of education 2017 (NCES 2017–144) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2017. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2017144. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery B. From deficits to possibilities: mentoring lessons from plants on cultivating individual growth through environmental assessment and optimization. 2017 Aug 27; https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/g83s9. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences (US), National Academy of Engineering (US), and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Underrepresented Groups and the Expansion of the Science and Engineering Workforce Pipeline. Expanding underrepresented minority participation. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); Academic and Social Support; 2011. p. 6. 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83369/ [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Research on interventions that promote research careers, RFA-GM-08-005. 2007. Retrieved August 2007 http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-GM-08-005.html.

- National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2015. Arlington VA: 2017. (Special Report NSF 17306). Available at https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2017/nsf17306/ [Google Scholar]

- Office of Diversity and Inclusion Wake Forest University. Embrace the strength in our differences. 2015. Retrieved on [26 July 2018] from https://business.wfu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/wfudiversitybrochure.pdf.

- Puritty C, Strickland LR, Alia E, Blonder B, Klein E, Kohl MT, McGee E, Quintana M, Ridley RE, Tellman B, Gerber LR. Without inclusion, diversity initiatives may not be enough. Science. 2017;357:1101–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaye SJ, Harper SR. Faculty accountability for culturally inclusive pedagogy and curricula. Liberal Education. 2007 Summer;93(3):32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WH, McGee EO, Bentley LC, Houston SL, Botchway PK. Addressing negative racial and gendered experiences that discourage academic careers in engineering. Comput Sci Eng. 2016;18:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Roll N. Should students be asked if professors are inclusive? Inside Higher Ed. 2017. Retrieved on [24 May 2018] from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/09/25/ball-state-debates-how-frame-diversity-question-teaching-evaluations.

- Schuman H, Steeh C, Bobo L, Krysan M. Racial attitudes in America: trends and interpretations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D, Dundar A, Huie F, Wakhungu P, Yuan X, Nathan A, Hwang YA. A national view of student attainment rates by race and ethnicity – Fall 2010 Cohort (Signature Report No. 12b) Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Powers LW. Raising the floor: sharing what works in workplace diversity, equity, and inclusion. White House Office of Science Technology; 2016. Retrieved on [25 May 2018] from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/11/28/raising-floor-sharing-what-works-workplace-diversity-equity-and-inclusion. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder TD, de Brey C, Dillow SA. Digest of education statistics 2014 (NCES 2016-006) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell R, Allum J, Okahana H. Doctoral initiative on minority attrition and completion. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley C. Reflections on changing a university’s diversity culture. Insight into diversity. 2016. Retrieved [17 January 2018] from http://www.insightintodiversity.com/reflections-on-changing-a-universitys-diversity-culture/

- Supiano B. Traditional teaching may deepen inequality. Can a different approach fix it? Chron High Educ. 2018. Retrieved on [26 July 2018] from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Traditional-Teaching-May/243339.

- Takayama K, Kaplan M, Cook-Sather S. Advancing diversity and inclusion through strategic multilevel leadership. AACU Liberal Education. 2017 Summer-Fall;103(3/4) [Google Scholar]

- Tanner KD. Structure matters: twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2013;12:322–331. doi: 10.1187/cbe.13-06-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate E. College completion rates vary by race and ethnicity, report finds. 2017. Retrieved [22 May 2018] from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/04/26/college-completion-rates-vary-race-and-ethnicity-report-finds.

- Treisman U. Studying students studying calculus: A look at the lives of minority mathematics students in college. Coll Math J. 1992;23:362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson W, Spalding A. Impact of "weed out" course achievement on STEM degree attainment among women and underrepresented minorities. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, Hilton Atlanta and Atlanta Marriott Marquis; Atlanta, GA. 2010. Online. 2014-11-27 from http://citation.allacademic.com/meta/p411398_index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Undergraduate College Wake Forest University. Diversity Action Plans. n.d. Retrieved on [27 July 2018] from http://college.wfu.edu/reporting-assessment/diversity-action-plans/

- United States Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS), October 1990–2015; U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, editor. Table 30260: Percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level of institution and sex and race/ethnicity of student: 1970 through 2015. Digest of Education Statistics. 2016 ed. 2016. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_302.60.asp.

- United States Department of Education Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development. Advancing diversity and inclusion in higher education: key data highlights focusing on race and ethnicity and promising practices. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2016. (Viewed 22 May 2018) < http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdf >. [Google Scholar]

- Utz R. The diversity question and the administrative-job interview. Chron High Educ. 2017. Retrieved on [02/11/2018] from https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Diversity-Questionthe/238914.

- Whittaker JA, Montgomery BL, Martinez-Acosta VG. Retention of underrepresented minority faculty: Strategic initiatives for institutional value based on perspectives from a range of academic institutions. J Undergrad Neurosci Educ. 2015;13:A136–A145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Berger JB, McClendon SA. Toward a model of inclusive excellence and change in postsecondary institutions. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities; 2005. https://inclusionandbelongingtaskforce.harvard.edu/publications/toward-model-inclusive-excellence-and-change-postsecondary-institutions. [Google Scholar]