Abstract

Aims

The diagnosis of cutaneous gamma delta T-cell lymphoma (GDTCL) requires the identification of γδ chains of the T-cell receptor (TCR). Using a new mAb to TCRδ, we evaluated TCRδ expression in formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) skin tissue from TCRγ-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and assessed TCRδ expression within a spectrum of other cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (CLPD).

Methods and results

12 cases (10 patients) with TCRγ-positive CTCL and 132 additional CLPD cases (127 patients) were examined including mycosis fungoides (MF, n=60), cutaneous GDTCL (n=15), subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphomas (SPTCL, n=11), and CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (CD30+LPDs, n=24). Clone H-41 to TCRδ (Santa Cruz; Houston, TX) was used on a Leica Bond-3 automated stainer to label FFPE slides. H-41 immunostaining was graded as percent infiltrate; high (50–100%), moderate (10–49%), low (0–9%). In TCRγ+ tumors, 12/12 (100%) patients showed TCRδ expression comparable to TCRγ. No (0%) TCRγ+ cases were negative for TCRδ. In all CLPD TCRδ expression follows: GDTCL (16/20 cases (14/15 patient) high, 2x moderate, 2x low); MF (0/60 cases high, 9x moderate, 51x low); CD30+ LPD (1/24 cases high, 2x moderate, 21x low); and SPTCL, (0/11 cases (0/9 patients) high, 2x moderate, 9x low). Three MF-like and one SPTCL-like cases showed high expression; the remainder were low.

Conclusions

MAb H-41 to TCRδ matches TCRγ in immunostaining FFPE tissues from GDTCL, supporting H-41 as a replacement for mAb γ3.20. TCRδ expression in our study suggests that the true occurrence of γδ+ non-GDTCL CTCL/CLPD may be lower than suggested by recent literature.

Keywords: T-cell lymphoma, Lymphoproliferative disorders, immunohistochemistry, immunologic techniques, classification

Introduction

Based on the differential expression of protein chains comprising the heterodimer of the T-cell receptor (TCR), T-cells can be divided into αβ and γδ T-lymphocytes. While the vast majority of circulating and peripheral T-cells are αβ lymphocytes and are part of the adaptive immune response, γδ T-cells are predominantly confined to a few specific anatomic compartments such as skin, mucosa and submucosa of the gastro-intestinal tract, where they are believed to defend against pathogens at the epidermal or mucosal surfaces with a rapid proinflammatory response as part of the innate immune system.1

Gamma-Delta T-cell lymphomas (GDTCL) are aggressive hematologic malignancies2 that predominantly evolve in spleen and liver (hepatosplenic type) or in skin with rapid progression and involvement of extracutaneous tissues (primary cutaneous GDTCL).3–5 Primary cutaneous GDTCL is a cytotoxic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) defined by the expression of TCR γδ, in the absence of expression of TCR αβ, and often in the absence of T-cell maturation markers.6, 7

Historically, GDTCLs were immunohistochemically characterized by the identification of the δ-1 TCR chain on frozen tissue8, or later, in formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissues, by verification of the absence of the TCRβ chain using a monoclonal antibody to TCRβ and cytotoxic marker expression.6 More recently, the presence of TCRγ could also be immunohistochemically detected in FFPE tissues employing monoclonal antibody (mAb) clone g3.20.9, 10 However, the use of an anti-TCRγ reagent for the detection of GDTCLs has not been without challenges. Atypical simultaneous expression of mutually exclusive TCR chains has been observed in lymphoma. TCRγ positivity, for example, has been described in cases with TCR αβ expression11–13 and monoclonal TCRβ gene rearrangements.14

In our study, we have validated the use of a monoclonal antibody to the TCRδ chain in FFPE tissue of CTCL. Additional objectives were to assess the utility of TCRδ labeling in FFPE for diagnostic and prognostic purposes in GDTCL, and within a spectrum of CTCL/CLPDs to see if the pattern of expression might be distinct from recently reported promiscuous patterns of TCRγ. Finally, we aimed to qualitatively characterize the presence of γδ T-cells in CTCL/CLPD in order to improve diagnostic/prognostic algorithms.

Materials and Methods

Tissue samples

The study was conducted with approval of the institutional review board of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. All included patients were evaluated and treated at our institution. Cases were identified by a pathology database and tissue archive search for cutaneous GDTCL and other CTCL/CLPD. A total of 144 skin biopsies from 137 patients were identified with sufficient available archival material. Clinical charts, anatomic, hematologic and molecular pathology reports and histologic and immunohistochemical material were reviewed.

The complete cohort of cases evaluated included 60 MF (44%), 15 primary cutaneous GDTCLs (11%), 11 subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphomas (SPTCL) (8%), 5 LyP (4%), 5 primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) (4%), 14 unspecified CD30+LPD (10%), 5 CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma (AETCL) (4%), 3 primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS (2%), 4 NK/T-cell lymphoma (3%), 3 CD4+ small/medium pleomorphic T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (SMPTCL)(2%), and 1 adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (<1%). Cases lacking unequivocal clinical certainty included 5 cases in which ALCL vs transformed CD30+MF were difficult to discern (4%), 3 TCRγ+ epitheliotropic lymphomas which have yet to declare themselves as MF with gamma+ phenotype or GDTCL (2%), and 3 panniculitic partial TCRγ+ lymphoma intermediate between GDTCL vs SPTCL (<1%). Clinical histories and presentation were elucidated for GDTCL cases and other cases with increased staining by TCRδ immunohistochemistry.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

H&E stained sections were reviewed in order to confirm diagnosis as per the 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.7 Previously performed and archived immunohistochemical stains were reviewed for T-cell marker expression including CD3, CD4, CD7, CD8, CD30, TCRβ, EBER-ISH and TCRγ. For straightforward MF or older cases of other CTCLs, available immunohistochemical stains often included only CD3, CD4, CD7, and CD8. Particularly, TCRβ and TCRγ were not available for these cases, being either not necessary for diagnosis, or not available at the time of diagnosis.

TCRδ Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis of the TCRδ chain was performed with mAb H-41 (SC-100289, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). H-41 (1:150; 0.7ug/ml) was used on an automated stainer platform (Leica Bond-3, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) using a heat-based antigen retrieval technique and hipH buffer solution (ER2, Leica) as previously described.15 TCRδ immunohistochemistry was performed for all 144 lesions. Based on our prior experience, in which lower percentages of TCRγ+ cells which couldn’t be unequivocally correlated with morphologically/immunophenotypically malignant cells due to low density and high mixed cell background, were disregarded in patients with subsequent more diagnostic biopsies of GDTCL, we opted to assess immunostaining for TCRδ as a percentage of total T-cell infiltrate. For the same reasons (suspected intratumoral variability), we accepted any intensity of cytoplasmic and/or membranous staining as positive. Each case received an individual numerical assignment, and was subsequently stratified into one of three categories based on the extent of TCRδ+ cells: low: 0–9% (baseline-negative comprised by scattered TCRδ positive cells), moderate: 10–49%, high:50–100%. All non-GDTCL CTCL with >10% labeling, all GDTCL with any labeling, and all cases of unclear disease type were further analyzed for pathologic distinctions and detailed clinical information.

Results

Clinical Data

Breakdown of the clinicopathologic diagnoses of the 137 patients is listed in Table 1. Further clinical data on the 40 cases with high and moderate TCRδ expression levels are presented below and in Table 2.

Table 1.

Percent of labeling of cutaneous LPD type by delta immunohistochemistry

| Cutaneous T-cell LPD | Number of cases (patients) | 0–9% cells | 10–49% cells | 50–100% cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycosis fungoides | 60 (60) | 51 | 9 | 0 |

| CD30 LPD | 24 (24) | 21 | 2 | 1 |

| SPTCL | 13 (11) | 11 (9) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| GDTCL | 20 (15) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 16 (14) |

| CD8+ cytotoxic CTCL | 5 (5) | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| NK/T cell lymphoma | 4 (4) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| PTCL NOS | 3 (3) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| CD4+ SMTCL | 3 (3) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| ATLL | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diagnostic conundrums | GDTCL vs SPTCL 4(3) | 0 | 4 (2) | 1 |

| GDTCL vs MF(3) | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| TMF vs CD30LPD (5) | 5 | 0 | 0 |

CLPD, cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder; LPD, lymphoproliferative disorder; SPTCL, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; GDTCL, gamma delta T-cell lymphoma; CTCL, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; NK, natural killer; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; SMTCL, small medium T-cell lymphoma; ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; MF, mycosis fungoides; TMF, transformed MF

Table 2.

High and moderate expressors (cases) of TCR Delta

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | Percent delta expression | Other information including time of follow up from first disease | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mycosis fungoides | 20 | Alive, folliculotropic, granulomatous, 39 months |

| 2 | Mycosis fungoides | 20 | Alive, hypopigmented lesions, 24 months |

| 3 | Mycosis fungoides | 25 | Alive, hypopigmented lesions, 5 months |

| 4 | Mycosis fungoides | 20 | Alive, PPD-like lesions, 24 months |

| 5 | Mycosis fungoides | 10 | Alive, patch lesion, 60 months |

| 6 | Mycosis fungoides | 25 | Alive, patch lesion, 59 months |

| 7 | Mycosis fungoides | 10 | Alive, Sezary syndrome/MF, 41 months |

| 8 | Mycosis fungoides | 15 | Alive, large cell transformation, 72 months |

| 9 | Mycosis fungoides | 15 | Alive, patch/plaque lesion 74 months |

| 10 | SPTCL | 10 | Died 6 months |

| 11 | SPTCL | 15 | Alive 180 months |

| 12 | CD30 LPD LYP | 10 | LFU solitary lesion |

| 13 | CD30 LPD LYP | 12 | Alive 84 months |

| 14 | CD30 LPD borderline | 90/80* | Alive 94 months |

| 15 | GDTCL vs. SPTCL | 10* | DOD 34 months |

| 16 | GDTCL vs. SPTCL | 20* | DOD 34 months |

| 17 | GDTCL vs. SPTCL | 30** | Alive 6 months |

| 18 | GDTCL vs. SPTCL | 40** | Alive 6 months |

| 19 | GDTCL vs. SPTCL | 70 | Alive 84 months |

| 20 | GDTCL vs. MF | 80 | Alive 84 months |

| 21 | GDTCL vs. MF | 100 | Alive 24 months |

| 22 | GDTCL vs. MF | 100 | Alive 1 month |

| 23 | GDTCL | 30*** | DOD 81 months |

| 24 | GDTCL | 30**** | DOD 111 months |

| 25 | GDTCL | 60 | Alive 3 months |

| 26 | GDTCL | 70**** | DOD 111 months |

| 27 | GDTCL | 70 | DOD 26 months |

| 28 | GDTCL | 70 | Alive 21 months |

| 29 | GDTCL | 80*** | DOD 81 months |

| 30 | GDTCL | 90 | LFU after 24 months |

| 31 | GDTCL | 90 | Alive 32 months |

| 32 | GDTCL | 95***** | DOD 17 months |

| 33 | GDTCL | 95***** | DOD 17 months |

| 34 | GDTCL | 95 | DOD 90 months |

| 35 | GDTCL | 100 | DOD 8 months |

| 36 | GDTCL | 100 | DOD 37 months |

| 37 | GDTCL | 100 | DOD 8 months |

| 38 | GDTCL | 100 | DOD 62 months |

| 39 | GDTCL | 100 | DOD 14 months |

| 40 | GDTCL | 100 | Alive 12 months |

GDTCL, gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma; SPTCL, subcutaneous panniculitis like T-cell lymphoma, LFU, lost to follow-up; DOD, Dead of disease; LPD lymphoproliferative disorder; MF, mycosis fungoides; PPD, pigmented purpuric dermatosis; LYP, lymphomatoid papulosis;

epidermis/dermis;

occurred in same patient

Pathologic data

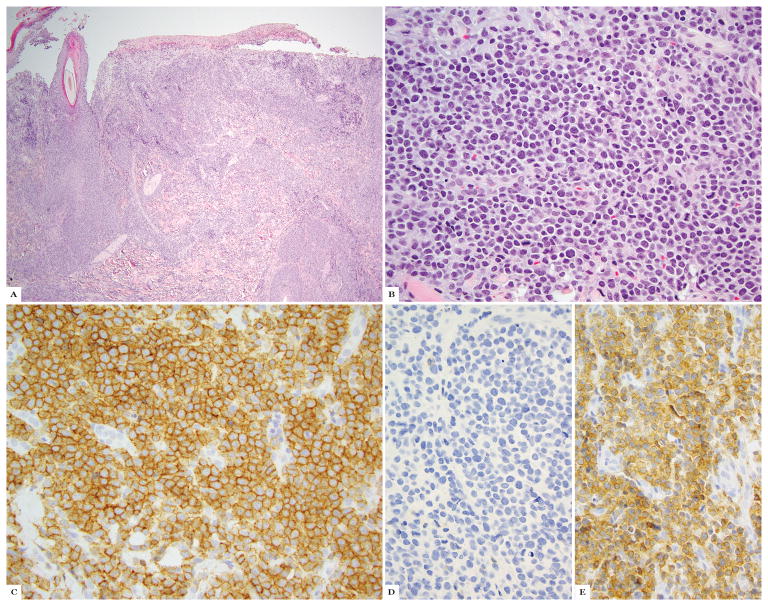

Of CTCL cases with strong and T-cell specific TCRγ expression, 12/12 (100%) showed high expression (50–100%) labeling with TCRδ (range 60–95%, mean 85%, median 82%) (Fig 1A–D).

Figure 1.

Primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma; A, B hematoxylin and eosin stain. C shows TCRδ immunohistochemistry, D shows TCRβ and TCRγ immunohistochemistry.

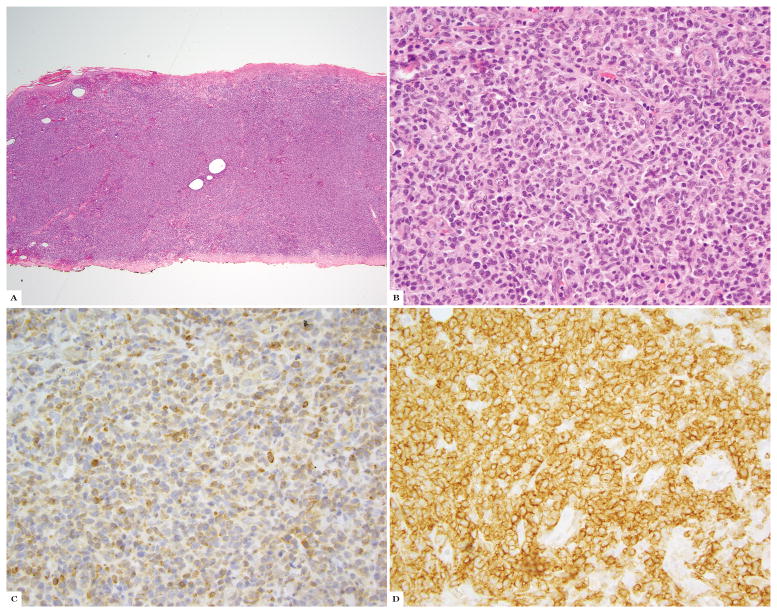

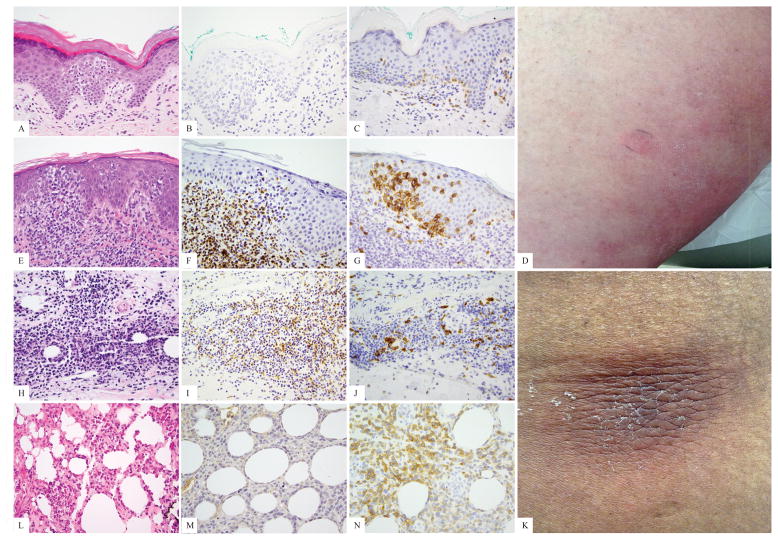

The percent of immunohistochemical staining in all CTCL biopsies is depicted in Table 1. Twenty-one of 144 (15%) of all cases showed high TCRδ labeling as follows: 16/20 (80%) GDTCL (14/15 (93%) patients), 1/24 CD30+LPD, 1/1 GDTCL vs SPTCL, and 3/3 unusual/CD4−/CD8− MF-like histologies. Nineteen of 144 cases (13%) showed moderate TCRδ+ infiltrates comprised by 2/20 (10%) GDTCL, 9/60 (15%) MF, 2/11 (18%) SPTCL, 2/24 (8%) CD30+LPD, and 4/4 (100%) unclear SPTCL versus GDTCL cases. The remainder of cases (106 cases; the majority of all lymphoma subtypes excluding GDTCL) were low. Twenty-one cases from 19 patients showed high numbers of TCRδ+ cells. Indeed 16/21 (76%) high expression cases (14/19 patients, 74%), were bona fide GDTCL cases. The remainder were not. One case was a TCRβ negative borderline CD30+LPD with 90% TCRδ labeling in the epidermal lymphocytes, and 80% TCRδ labeling in the dermal lymphocytes; this patient is alive 94 months after diagnosis with occasional solitary lesions easily treated with surgery or XRT to individual lesions (Fig 2A–D). One patient was considered clinicopathologically to have SPTCL (occasional subcutaneous nodules that localized to the adipose tissue with a CD8+ infiltrate), and is alive 84 months after diagnosis with responses to different therapies, despite 70% TCRδ+ T-cells in this study (Fig 3L–M). In this patient, immunohistochemistry was performed as a negative control for TCRγ validation, and for the purpose of this study on TCRδ, and the strong positive result was a surprise. Three patients were diagnosed as having epidermotropic T-cell lymphomas with CD4−/CD8− diffuse TCRδ intraepidermal positivity (80%, 100% and 100%), but so far with an indolent clinical course and an MF-like clinical appearance of patches and plaques (84, 24 and 1 month survival at the time of this study) (Fig 3A–G).

Figure 2.

TCRγδ expression in a borderline primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder: A, B, Hematoxylin and eosin; C, 80% TCRδ in dermis; D, Immunohistochemistry for CD30 in dermal population.

Figure 3.

Examples of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas with clinical behavior of mycosis fungoides or subcutaneous panniculitis like T-cell lymphoma, and prominent TCRγδ phenotype as shown by TCRδ immunohistochemistry. A–D, hematoxylin-eosin, TCRβ, TCRδ, and clinical patch lesions in a patient with a mycosis fungoides presentation and 84 months of follow-up; E–G, hematoxylin-eosin, TCRβ, and TCRδ in a recently diagnosed patient with a mycosis fungoides-like presentation; H–K hematoxylin-eosin, TCRβ, TCRδ, and clinical subcutaneous nodule in a panniculitic patient with indolent course through limited (several month) follow up; L–N, hematoxylin-eosin, TCRβ, and TCRδ in a panniculitic presentation with indolent course through 84 months.

Of nineteen cases with moderate TCRδ+ infiltrates, nine (50%) were MF patients, and two each were GDTCL, SPTCL or CD30+LPD patients (11% each) (Fig 3H–K). MF patients’ infiltrates harbored up to 10–25% γδ T-cells, and were not diagnostically confusing, whereas the other cases in the moderate category were more difficult.

Four cases from 3 patients with known GDTCL showed low (2) or moderate (2) labeling. To better understand this unexpected finding, we re-examined the cases. The first case showed only limited patch-disease with no TCRγ reactivity in the original biopsy, despite later biopsies that progressed to pathologic TCRγ+ tumors and consecutive death. One patient’s biopsy showed only 30% positivity, which on retrospective review was the best characterization of a limited low tumor-burden lymphoid infiltrate in almost-exhausted tissue. Two biopsies from a third patient showed 1% and 30% TCRδ labeling respectively, but the TCRβ immunostain on each was difficult to interpret, suggesting that the sample was not adequate for meaningful pathologic assessment despite molecular monoclonality. A later biopsy in this patient showed clear-cut GDTCL with 70% TCRδ staining and was positive for TCRγ at an outside institution.

TCRδ delineated lymphoma and clear-cut GDTCL; survival

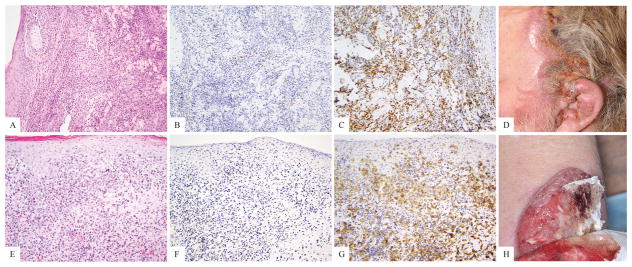

10/19 patients (53%) with TCRδ positive cells comprising 50–100% of their infiltrates, died in follow-up, all of whom were GDTCL patients. Two of them had been thought to have MF with large cell transformation, but were reclassified upon review of charts and evaluation of immunohistochemical staining patterns as GDTCL (Fig 4A–H). No clinicopathologically equivocal patient with TCRδ positive cells comprising 50–100% of their infiltrates died in follow up.

Figure 4.

Two patients with primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, retrospectively classified as gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma upon review of their clinical history, after tissue evaluation with TCRδ immunohistochemistry. A–D hematoxylin and eosin, TCRβ, TCRδ and clinical images illustrating a large facial tumor in the absence of patches or plaques. E–H, hematoxylin and eosin, TCRβ, TCRδ and clinical image showing a large ulceration in the absence of patches or plaques.

In total 10/15 clear-cut GDTCL patients (67%, 10/14 GDTCL patients with high TCRδ) died. One patient was lost to follow up. Seven of the GDTCL patients who died (7/10, 70%) showed both intraepidermal and dermal and/or subcutaneous TCRδ expressing lymphocytes. One patient had dermal-only localization of TCRδ+ lymphocytes. One patient had an initial intraepidermal TCRδ, TCRγ, CD4 and CD8 negative presentation but developed systemic disease with florid visceral TCRδ+ tumors. Three GDTCL patients who are currently alive showed mixed intraepidermal and dermal/subcutaneous TCRδ+ T-cells, one had dermis-limited tumor, and the patient lost to follow up had a biopsy of fat only (no epidermis present to assess).

Discussion

Cutaneous GDTCL is a distinct aggressive rare cutaneous lymphoma, comprising <1% of all skin lymphomas. It presents with variable clinical features and histological patterns and therefore its diagnosis is challenging.6,3 Due to the lack of a reliable marker of γδ T-lymphocytes in routine FFPE tissue sections, a presumptive diagnosis used to rely on the absence of αβ TCR expression using a monoclonal antibody to TCRβ.6 However, it is known that TCRβ expression may be lost by neoplastic αβ T-cells and therefore the lack of TCRβ cannot and should not be used to assure a γδ origin.9, 16 Specific antibodies that label γ or δ chains of the γδ TCR heterodimer can allow recognition of γδ T-cells in skin tissue and are more specific for GDTCL diagnosis. Routine immunolabeling with a γ chain marker in FFPE tissue (clone gamma 3.20)3, 12, 14 had been used successfully for this purpose, but recently became unavailable. Additional challenges with the use of TCRγ protein have included the potential for its more promiscuous expression in αβ lymphomas, as translation and expression of the TCRγ chain may occur in the context of TCRβ gene rearrangement whereas the TCRδ gene is deleted in that context, pre-empting TCRδ expression. This suggests that the presence of TCRδ expression could be yet more specific in the diagnosis of GDTCL than TCRγ. In the current study we aimed to evaluate the detection and occurrence of γδ T-cells in CTCL and CLPDs using the mAb H-41 to TCRδ in FFPE tissue and we have found that TCRδ expression is comparable to TCRγ labeling in TCRγ+ tumors, with 12/12 cases positive for both TCR chains. All cases that were strongly and diffusely TCRγ positive were also TCRδ positive; we did not identify any TCRγ+ cases that were TCRδ−. TCRγ and TCRδ appeared to label the same cell populations in the examined biopsies although some samples were not sequentially assayed (Fig 1). None of the TCRδ+ cases was found to co-express TCRβ.

In normal skin, γδ T-cells are extremely rare, comprising less than 1% of all CD3 positive cells, although up to 30% of intraepidermal T-cells,17–19 while GDTCL is characterized by predominantly TCRδ+ T-cell infiltration.6 All GDTCL patients in our study were TCRδ+, with 93% of the patients (14/15) and 80% of their studied biopsies (16/20) showing high labeling of 50%–100% of the lymphocytic infiltrate. On retrospective review, outliers were explainable by sampling error. TCRδ expression in 30% of the infiltrate was revealed in one patient who went on to have another biopsy six years later showing 80% labeling. While we considered that this change in expression could represent disease evolution, upon review of the early biopsy, the tissue was found to be nearly exhausted at the time of TCRδ staining, precluding accurate interpretation. Two cases showed 0% and 1% TCRδ expression, however additional biopsies from each of these showed high TCRδ expression; one patient died within a year of florid GDTCL, and the other had a synchronous biopsy showing 70% labeling. This suggested either that we had reviewed early non-diagnostic disease (in the former case), or inadequately sampled or poorly processed tissue (in either case).

As expected, a high mortality rate was found among GDTCL patients in our study (67%, 10/15). Unexpectedly, 70% (7/10) of GDTCL patients who died from disease showed histologic involvement of both intraepidermal and dermal and/or subcutaneous skin compartments, versus 60% (3/5) of GDTCL patients who were alive at last follow up. This pattern of skin involvement in aggressive disease is not in line previous reports on decreased survival in cases with subcutaneous versus epidermotropic or dermal GDTCL4. Our findings align more closely with reports of intraepidermal MF-like GDTCL noted to evolve into aggressive cytotoxic lymphomas after many years of follow up.20 We concur that caution is warranted when following such patients. Of note, we did not include CD4−/CD8−, TCRδ high patch/plaque type T-cell lymphomas within our MF cohort, as we feel that the follow-up on these cases is too limited for meaningful classification. However, inclusion of such cases within our survival analysis of TCRδ high infiltrates, resulted in improved OS when compared to clear cut clinicopathologic GDTCL (67% vs 53%), suggesting that a decision to include such cases as GDTCL needs further study.

Numerous γδ expressing T-cells can be found not only in GDTCL, but also in low-grade CTCL, CLPDs14, and inflammatory self-limited and indolent skin conditions10, 17, 20, 21 In our study, 13 cases with typically indolent CTCL and CLPDs were shown to have lymphocytic infiltrates with 10%–25% TCRδ positivity, including 9 MF cases, 2 SPTCLs and 2 CD30-positive LPDs. One case of CD30-positive LPD showed TCRδ expression in 80–90% of the T-cell infiltrate and negative TCRβ labeling. This unusual case presented with indolent, recurrent lesions and was similar to the recently published six γδ T-cell-rich LyP cases that were identified by TCRγ+ and/or βF1-negative immunostaining.21 Identification of γδ T-cells by use of TCRδ stain in our cases supports that bona fide γδ T-cells comprise components of similar infiltrates. In such indolent CTCL/CLPD, γδ T-cells have been reported as up to 20% of lymphocytes. It has been suggested that these cells may represent either a subset of the malignant clone or a reactive T-cell population.20 While we did not comparatively assess the intensity of staining within the different compartments of individual patients’ infiltrates in this study, we did observe qualitative differences in staining between small peripheral or intraepidermal TCRδ+ cells and larger clearly neoplastic cells. Comprehensive characterization of these subsets may help to better understand these diseases in the future. For now, given our experience, with 90% of MF cases showing fewer than 9% γδ T-cells, and the remainder with 10–25%, we suggest closer clinical surveillance and possibly additional biopsies when infiltrates are comprised of greater than 25% γδ T-cells.

Finally, TCR-γ expressing T-cells have been described within CD8+ AETCL, and may confound the diagnosis.22 However, in our study all five (5/5) AETCLs were negative for γδ T-cells by TCRδ IHC, suggesting that TCRδ may have a better negative predictive value for AETCL than TCRγ. Larger numbers of AETCL should be evaluated to better assess this possibility.

Overall, our findings highlight the need for cautious evaluation even when low expression of γδ (<10%) is identified if the clinical picture is not consonant with the pathologic interpretation, given that two of our GDTCL patients who initially had low-labeling of TCRδ died. Repeated biopsies of multiple sites and lesions in a manner that allows proper evaluation of the relevant tissue depth, (sampling the subcutis in panniculitis-like lesions), and consideration of flow cytometric evaluation, are needed to compensate for any possible sampling errors, fixation problems, and disease evolution. In cases of intermediate to high TCRδ labeling, in which diagnosis remains unclear, close follow-up is vital and re-biopsy of any change is mandated.

In conclusion, mAb H-14 to TCRδ is comparable to TCRγ immunohistochemistry and is reliable for the detection of TCRδ chain in malignant and potentially reactive γδ T-cells in FFPE skin tissue specimens of CTCL/CLPD. While high numbers of TCRδ expressing T-cells are most often diagnostic for GDTCL, lower numbers of TCRδ+ cells can be found in indolent CTCL and CLPDs. As outliers to these conventions may exist, assurance of adequacy of biopsy and cautious follow-up are essential in all cases with positive TCRδ labeling.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

A conflict of interest statement:

SH has consulting relationships with Celgene Millenium/Takeda Kyowa-Hakka-Kirin Seattle Genetics Forty-Seven Mundipharma Verastem, and research relationship with Celgene Millenium/Takeda Kyowa-Hakka-Kirin Seattle Genetics Forty-Seven Infinity/Verastem Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, ADCT Therapeutics and Aileron Therapeutics. AM consulting relationships with Seattle Genetics and BMS. MP, SG, DF, PM, MK, AC, AD and AJ have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions - Melissa Pulitzer – concept design, data acquisition, analysis & interpretation writing/drafting, supervision, critical revision; Shamir Geller – writing/drafting, data acquisition, analysis & interpretation, critical revision; Denise Frosina – data acquisition (performed IHC), critical revision; Allison Moskowitz, Steven Horwitz, Patricia Myskowski, Meenal Kheterpal, Alexander Chan – data acquisition, critical revision; Ahmet Dogan – analysis/interpretation, critical revision; Achim Jungbluth – data acquisition (performed IHC), writing/revising

References

- 1.Taghon T, Rothenberg EV. Molecular mechanisms that control mouse and human tcr-alphabeta and tcr-gammadelta t cell development. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:383–398. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tripodo C, Iannitto E, Florena AM, et al. Gamma-delta t-cell lymphomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:707–717. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guitart J, Weisenburger DD, Subtil A, et al. Cutaneous gammadelta t-cell lymphomas: A spectrum of presentations with overlap with other cytotoxic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1656–1665. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826a5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta t-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous t-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407–3412. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like t-cell lymphoma: Definition, classification, and prognostic factors: An eortc cutaneous lymphoma group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838–845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. Who-eortc classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the world health organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groh V, Porcelli S, Fabbi M, et al. Human lymphocytes bearing t cell receptor gamma/delta are phenotypically diverse and evenly distributed throughout the lymphoid system. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1277–1294. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Herrera A, Song JY, Chuang SS, et al. Nonhepatosplenic gammadelta t-cell lymphomas represent a spectrum of aggressive cytotoxic t-cell lymphomas with a mainly extranodal presentation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1214–1225. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822067d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roullet M, Gheith SM, Mauger J, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Choi JK. Percentage of {gamma}{delta} t cells in panniculitis by paraffin immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:820–826. doi: 10.1309/AJCPMG37MXKYPUBE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vin H, Talpur R, Tetzlaff MT, Duvic M. T-cell receptor-gamma in gamma-delta phenotype cutaneous t-cell lymphoma can be accompanied by atypical expression of cd30, cd4, or tcrbetaf1 and an indolent clinical course. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:e195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi Y, Takata K, Kato S, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of 17 primary cutaneous t-cell lymphoma of the gammadelta phenotype from japan. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:912–923. doi: 10.1111/cas.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pongpruttipan T, Sukpanichnant S, Assanasen T, et al. Extranodal nk/t-cell lymphoma, nasal type, includes cases of natural killer cell and alphabeta, gammadelta, and alphabeta/gammadelta t-cell origin: A comprehensive clinicopathologic and phenotypic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:481–499. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824433d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Ortiz-Romero PL, Monsalvez V, et al. Tcr-gamma expression in primary cutaneous t-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:375–384. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318275d1a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jungbluth AA, Frosina D, Fayad M, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of gamma/delta t lymphocytes in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018 doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Sanchez ME, Rodriguez J, et al. Loss of tcr-beta f1 and/or ezrin expression is associated with unfavorable prognosis in nodal peripheral t-cell lymphomas. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e111. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupuy P, Heslan M, Fraitag S, Hercend T, Dubertret L, Bagot M. T-cell receptor-gamma/delta bearing lymphocytes in normal and inflammatory human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:764–768. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vroom TM, Scholte G, Ossendorp F, Borst J. Tissue distribution of human gamma delta t cells: No evidence for general epithelial tropism. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:1012–1017. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.12.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bos JD, Teunissen MB, Cairo I, et al. T-cell receptor gamma delta bearing cells in normal human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:37–42. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12873333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guitart J, Martinez-Escala ME. Gammadelta t-cell in cutaneous and subcutaneous lymphoid infiltrates: Malignant or not? J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1242–1244. doi: 10.1111/cup.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Escala ME, Sidiropoulos M, Deonizio J, Gerami P, Kadin ME, Guitart J. Gammadelta t-cell-rich variants of pityriasis lichenoides and lymphomatoid papulosis: Benign cutaneous disorders to be distinguished from aggressive cutaneous gammadelta t-cell lymphomas. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:372–379. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guitart J, Martinez-Escala ME, Subtil A, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic t-cell lymphomas: Reappraisal of a provisional entity in the 2016 who classification of cutaneous lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:761–772. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]