Abstract

Objective

To compare the quality of care following admission to a nursing home (NH) with and without a dementia special care unit (SCU) for residents with dementia.

Data Sources/Study Setting

National resident‐level minimum dataset assessments (MDS) 2005–2010 merged with Medicare claims and provider‐level data from the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting database.

Study Design

We employ an instrumental variable approach to address the endogeneity of selection into an SCU facility controlling for a range of individual‐level covariates. We use “differential distance” to a nursing home with and without an SCU as our instrument.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Minimum dataset assessments performed at NH admission and every quarter thereafter.

Principal Findings

Admission to a facility with an SCU led to a reduction in inappropriate antipsychotics (−9.7 percent), physical restraints (−9.6 percent), pressure ulcers (−3.3 percent), feeding tubes (−8.3 percent), and hospitalizations (−14.7 percent). We found no impact on the use of indwelling urinary catheters. Results held in sensitivity analyses that accounted for the share of SCU beds and the facilities' overall quality.

Conclusions

Facilities with an SCU provide better quality of care as measured by several validated quality indicators. Given the aging population, policies to promote the expansion and use of dementia SCUs may be warranted.

Keywords: Nursing home, quality, dementia, special care unit

On a given day, approximately 750,000 individuals residing in U.S. nursing homes have a diagnosis of dementia, constituting 50 percent of long‐stay residents nationally (National Center for Health Statistics [U.S.] 2016). Between 30 and 40 percent of adults with dementia reside in nursing homes, and approximately 70 percent of Americans with dementia will die in a nursing home (Mitchell et al. 2005). The quality of care provided to these individuals is often substandard (Teno et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2004, 2016; Sachs, Shega, and Cox‐Hayley 2004).

One well‐utilized approach aimed at improving quality of care in this population is admission to a dementia special care unit (SCU). Although no national standard for SCUs exists, they are most commonly specialized wards within nursing homes where the structural design, staffing features, and activity programs are designed with the goal of providing a supportive social environment and prosthetic physical environment for older adults with dementia. Dementia SCU beds make up 4.5 percent of all nursing home beds and are the most common form of special care units, comprising 72 percent of all special care beds (Alzheimer's Association 2014).

Despite the widespread adoption of this approach to care, their effects on care quality are unclear. A number of papers have investigated the impact of SCUs on patient outcomes and found mixed results (Reimer et al. 2004; Gruneir et al. 2008a; Luo et al. 2010; Cadigan et al. 2012; van der Putten et al. 2014). In a Cochrane review of this literature, Lai et al. (2009) stated that not enough information exists to conclude that SCUs improve measures of cognitive decline or process measures related to quality of care, such as the use of antipsychotics and restraints, and that “It is probably more important to implement best practice than to provide a specialized care environment.” Importantly however, Lai et al. also stressed that the studies included in this review are based on potentially confounded research designs. Whether a nursing home resident with dementia is admitted to an SCU facility is not random. These individuals may systematically differ from individuals admitted to non‐SCU facilities on a series of unobservable characteristics such as their prognosis and the presence of family oversight. Thus, simple comparisons of outcomes across SCUs and traditional units, even after controlling for observable characteristics, may yield biased estimates of the effect of SCUs on discharge outcomes. Furthermore, previous work has suggested that any observed improvements in quality of care associated with SCUs may reflect the quality of the facility overall, and not the effect of the SCU itself (Gruneir et al. 2007, 2008a, b). Consequently, the causal effect of SCUs on patient outcomes is unknown.

This study addresses this knowledge gap with the use of an instrumental variable to account for the potential selection of patients into facilities with SCUs. Specifically, we instrument for choice of an SCU using differential distance from the patient's home to the nearest nursing home with and without an SCU. The objective of our analysis is to estimate the effect of admission to a facility with an SCU on quality of care for individuals with dementia. Because distance is important toward predicting nursing home choice and an individual chooses where to live without regard as to whether nearby nursing homes have an SCU, the identifying assumption is that the instrument will be correlated with the selection of a nursing home with an SCU but independent of patient‐specific measures that would determine selection. We study quality of care through process measures especially relevant to patients with dementia, including the use of antipsychotics and restraints, as well as indicators of quality of care more broadly relevant to the nursing home population, including the use of feeding tubes and urinary catheters, the presence of pressure ulcers, and the occurrence of hospitalizations. In addition, we include two additional analyses to test the hypothesis that nursing homes with an SCU are simply higher quality facilities than nursing homes without an SCU.

Data

All individual‐level data came from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) 2.0 Nursing home Assessment for years 2005–2010 (Phillips and Morris 1997). The MDS is a comprehensive assessment performed for all nursing home residents upon admission and then every quarter thereafter, or more often if a patient's clinical status changes significantly. The assessment contains nearly 400 data elements covering demographics, physical and cognitive functioning, chronic and acute diagnoses, and medications dispensed and procedures conducted during the patient's stay. To identify patient hospitalizations, we merged data from the MDS to eligibility data from the Medicare enrollment files and the Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR) file containing the inpatient hospital claims. Facilities with an SCU were identified from the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting (OSCAR) database, which is a survey of all certified nursing homes in the United States conducted approximately every 18 months. The survey collects information on nursing home characteristics such as facility size, staffing levels, and patient mix. Most importantly, it also collects information on the number of SCU beds in a facility (Gruneir et al. 2007, 2008a).

Study Cohort

We restricted our study cohort to fee‐for‐service Medicare eligible individuals who were “newly admitted” to a nursing home between 2005 and 2010 with a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or dementia (hereafter referred to as dementia only) at the time of admission. Because we exploit choice of a nursing home with or without an SCU, it is important to identify individuals who have not previously been admitted to a nursing home. Thus, we considered patients to be newly admitted if this was the first nursing home admission after a minimum of 12 months and included only the first eligible admission to a nursing home.

Dementia was identified by either the ICD‐9 code (290.x) or by the indicator for Alzheimer's disease or dementia in section I (Disease Diagnoses) on the admission MDS assessment. Following admission, the patient's follow‐up time through discharge was divided into quarterly assessments and patient outcomes were measured in each quarter. We further limited the cohort to individuals admitted to a facility with greater than 20 beds (99 percent of facilities) and long‐stay residents, which we defined as residents with at least 100 days in the nursing home following admission. A total of 704,782 individuals met the eligibility criteria with a median follow‐up time of 7.6 quarterly assessments.

Quality of Care Outcome Variables

We examined a series of quality measures that have been studied frequently in the literature (Zimmerman 2003; Gruneir et al. 2008b; Cadigan et al. 2012). Specifically, in each person‐quarter, we analyzed the presence of inappropriate antipsychotic use and the use of physical restraints, both of which have been shown to be especially dangerous for patients with dementia (Foebel et al. 2016). Inappropriate antipsychotic use was identified according to a previously published definition which excludes individuals with FDA approved indications for antipsychotics as well as those meeting the Resource Utilization Group (RUGs‐III) definition of severe behavioral symptoms (Lucas et al. 2014). Additional outcomes included use of feeding tubes and indwelling urinary catheters, neither of which have been shown to improve quality of life for patients with dementia and instead can pose serious risks (Gillick 2000; Holroyd‐Leduc et al. 2007; Kuo et al. 2009), and the presence of pressure ulcers which are often an indicator that a patient is not being moved enough (Berlowitz et al. 1997). Lastly, we also examined the occurrence of hospitalizations, which are often avoidable (Saliba et al. 2000) and can be especially burdensome for patients with dementia (Givens et al. 2012; Feng et al. 2014). All outcome measures are reported to CMS and are included as quality measures on the Nursing Home Compare website, with the distinction that all antipsychotic use is reported as opposed to inappropriate use only (Werner, Konetzka, and Kim 2013).

Dementia Special Care Units

Our exposure of interest was admission to a nursing home with a dementia SCU. In our primary analysis, we defined a facility reporting one or more SCU beds on the OSCAR survey as having an SCU, while in additional analyses we used the percent of beds in a facility designated as SCU beds.

Covariates

We included several individual‐ and geographic‐level covariates known to confound the relationship between admission to a facility with an SCU and quality of care (Sloane et al. 1995; Gruneir et al. 2008a). Individual‐level characteristics included demographics (age, gender, race, marriage status, dually eligible to Medicaid and Medicare and if the patient was enrolled in a health maintenance organization [HMO]), cognitive and psychological diagnoses (hallucinations, delusions, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, level of cognitive impairment as measured by the Cognitive Performance Scale [Morris et al. 1994], the Burrows depression scale [Burrows et al. 2000] and activities of daily living [Morris, Fries, and Morris 1999]) chronic disease diagnoses (hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke), and advanced directives (do not hospitalize, do not resuscitate). All individual‐level covariates were obtained from the MDS assessment on admission. Characteristics of the resident's home zip code were obtained by linking individuals to data from the 2011–2015 American Community Survey and 2010 Decennial Census at the level of the zip code. Specifically, we included information on median income, education (percent with high school equivalence and percent with a bachelor's degree), insurance status (percent with public insurance and percent uninsured), percent unemployed, percent above age 65, and percent of the zip code classified as rural, defined as the area not within an urban area (Hart, Larson, and Lishner 2005).

Statistical Analysis

To account for the endogeneity of facility choice, we instrument for admission to a facility with an SCU using the differential distance from the individual's home to a facility with an SCU relative to a facility without an SCU. To construct this measure of differential distance, we geocoded the address for each nursing home which we obtained from the OSCAR survey. We then calculated measures of distance as the straight line from the centroid of the individual's zip code to the nearest nursing home with and without an SCU using the GEODIST macro in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). The differential distance was then constructed as the distance to the nearest facility with an SCU minus the distance to the nearest facility without one (see Figure S1). We used the difference in the natural log of the distances to provide a relative measure of differential distance.

We first estimated a model that treats SCU status as exogenous. In this “naïve” approach, we fit a linear probability model in which we regressed quality of care measures on a binary indicator for SCU, controlling for individual‐ and geographic‐level covariates along with fixed effects for state, year, and period following admission. Robust standard errors were clustered at the level of the facility (Bertrand, Duflo, and Mullainathan 2004). We estimated the following model:

| (1) |

where Y ip is the quality of care measured for person i in period p, SCUi is a binary indicator of whether the facility has an SCU on admission (0 = no, 1 = yes), X i is a vector of individual‐level covariates measured on admission, λ i represents state fixed effects (and thus neither SCUi, X i nor λ i vary over p), τ ip represents year and period fixed effects, and ɛ ip is the error term.

To account for the endogeneity of facility choice, we employed a two‐stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variable analysis in which fitted values () from the first‐stage estimates of the regression of SCU on differential distance, DD i (equation (2)), replace the endogenous measure of SCU from the naïve estimation (equation (3); Angrist and Imbens 1995). In both equations, we included all covariates from the naïve estimation and include robust standard errors clustered at the level of the facility

| (2) |

| (3) |

Model Assumptions and Checks

In order to interpret our estimate as an unbiased effect of admission to a facility with an SCU on quality of care, our instrument needs to satisfy several assumptions. First, we assume that differential distance is negatively correlated with admission to a facility with an SCU. We base this assumption on a large body of literature demonstrating that distance is a strong driver of provider choice, including nursing homes (Hartmaier et al. 1994; McClellan, McNeil, and Newhouse 1994; Phillips and Morris 1997; Hirth et al. 2014; Paksarian et al. 2016; Gadbois, Tyler, and Mor 2017). Thus, the greater the distance that an individual must travel to a nursing home with an SCU relative to a nursing home without an SCU, the less likely that individual is to be admitted to a facility with an SCU. An empirical test of this assumption comes from the first stage of the 2SLS estimation procedure, in which admission type (to a facility with or without an SCU) is regressed on differential distance. A second assumption is that the instrument is uncorrelated with the error term in the second stage estimation. A violation of this assumption could occur if individuals choose their residence based on the SCU status of the nearest nursing home, or nursing homes with SCUs chose their location based on the characteristics of the local population differently than nursing homes without SCUs. We can test the first assumption by regressing differential distance on our endogenous variable (SCU, yes no). A large F‐statistic (generally accepted as >10) suggests there is a strong relationship between our instrument and SCU status of the facility (Staiger and Stock 1997). However, the second assumption can only be evaluated on the set of observables measured in the MDS and census. Evidence suggesting that differential distance is independent of the set of observed characteristics leads to greater confidence that it is also independent of unobserved confounders, although this is not possible to prove.

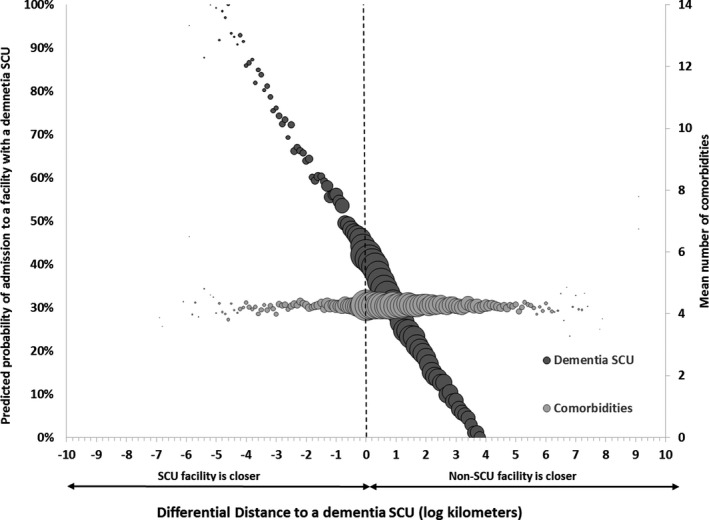

To test the first assumption, in Figure 1 we present a scatterplot based on work by Brooks et al. (2006) depicting the relationship between differential distance and admission to a facility with an SCU. On the x‐axis, we plot the values of differential distance rounded to the nearest 0.01 of a kilometer. On the left y‐axis in dark gray, we plot the predicted probability of admission to facility with an SCU obtained from the first‐stage estimation (equation (2)). From the figure, we can clearly see a strong negative relationship between differential distance and probability of admission to an SCU. Patients who live closer to an SCU facility are more likely to be admitted to a facility with an SCU, while patients who live closer to a non‐SCU facility are less likely to be admitted to a facility with an SCU. After accounting for clustering, the F‐statistic for the instrument from the first‐stage regression is 115 (df = [81, 15,344], p < .001), which meets the Staiger and Stock (1997) standard of being a strong instrument. On the right y‐axis, we plot the mean number of comorbidities at each value of the differential distance in light gray. The following conditions were included in the measure of comorbidities on admission: severe cognitive impairment, short‐term and long‐term memory loss, hallucinations, delusions, severe behavior as measured on the Resource Utilization Group Scale (RUGS) III (Fries et al. 1994), bipolar disorder, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, diabetes, and hypertension. In contrast to relationship between differential distance and admission to a facility with an SCU, we can see that there is no evidence of a relationship between the mean number of comorbidities and differential distance, suggesting good balance when individuals are sorted by the instrument. Again, we demonstrate this statistically by providing the correlation coefficient (CC) and associated p‐value (CC = 0.002, p = .113).

Figure 1.

- Notes: Area of the bubble represents relative sample size at each measure of differential distance rounded to the nearest 0.1 km. Comorbidities include severe cognitive impairment, age greater than 85, hallucinations, delusions, severe behavior as measured on the Resource Utilization Group Scale (RUGS) III, bipolar disorder, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, diabetes, and hypertension. Probabilities are adjusted for covariates reported in Table 1, as well as state, year, and period fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the level of the facility (number of facilities = 15,743).

To further evaluate the second assumption, we compared the prevalence of all measured covariates and census characteristics of the patient's zip code by the median differential distance (0.9 km) (see Table 1). Because of our large sample size, small differences in the mean that are not substantively important may still be significantly different. Thus, in addition to the p‐value for each comparison, we provide the standardized mean difference, which is a comparison of means standardized by the pooled standard deviation, and thus is not influenced by sample size. Values between −0.1 and 0.1 are not considered meaningfully different. Once again, we see little evidence of a relationship between the observed covariates and differential distance. Although the vast majority of covariates were statistically different, most were within the −0.1 to 0.1 boundary of the standardized mean difference, except for white race, which was less prevalent above the median (83 vs. 87 percent), and dual eligibility status, which was more prevalent above the median (28 vs. 34 percent). Geographic characteristics of the patients' zip code tended to differ the most. Individuals with a differential distance above the median lived in zip codes that were more rural (23.6 vs. 18.3 percent), with a higher prevalence of uninsured (12.7 vs. 11.6 percent) and public insurance (34.7 vs. 33.4 percent) as well as lower prevalence of individuals with a bachelor's degree (8.0 vs. 8.1 percent).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Residents with Dementia Admitted to a Nursing Home Stratified by the Median Differential Distance (DD)—0.9 km—from the Zip‐Code Centroid of the Individual's Residence to the Nearest Nursing Home with and without a Dementia Special Care Unit

| DD < Median | DD ≥ Median | p‐Value | Std. Mean Diff. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| n | 345,751 | – | 359,031 | – | – | – |

| Age | 83.1 | (8.2) | 82.9 | (8.4) | <.0001 | −0.02 |

| Female | 235,656 | 68.16 | 245,763 | 68.45 | 0.036 | 0.01 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 301,557 | 87.22 | 297,585 | 82.89 | <.0001 | −0.12 |

| Black | 32,112 | 9.29 | 43,493 | 12.11 | <.0001 | 0.09 |

| Married | 97,622 | 28.23 | 95,720 | 26.66 | <.0001 | −0.04 |

| Dual eligible | 97,968 | 28.33 | 120,542 | 33.57 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| In an HMO | 53,423 | 15.45 | 52,702 | 14.68 | <.0001 | −0.02 |

| Hallucinations | 10,239 | 2.96 | 10,245 | 2.85 | .134 | −0.01 |

| Delusions | 20,716 | 5.99 | 19,686 | 5.48 | <.0001 | −0.02 |

| Bipolar | 5,873 | 1.70 | 6,409 | 1.79 | .049 | 0.01 |

| Schizophrenia | 6,412 | 1.85 | 7,966 | 2.22 | <.0001 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety | 52,371 | 15.15 | 54,522 | 15.19 | .012 | 0.00 |

| Cognitive impairment | ||||||

| Mild | 75,785 | 21.92 | 83,607 | 23.29 | <.0001 | 0.03 |

| Moderate | 212,557 | 61.48 | 213,371 | 59.43 | <.0001 | −0.04 |

| Severe | 57,345 | 16.59 | 61,996 | 17.27 | <.0001 | 0.02 |

| Depression | 130,640 | 37.78 | 131,221 | 36.55 | <.0001 | −0.03 |

| Hypertension | 235,855 | 68.22 | 247,485 | 68.93 | <.0001 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 83,103 | 24.04 | 89,951 | 25.05 | <.0001 | 0.02 |

| COPD | 47,817 | 13.83 | 51,155 | 14.25 | <.0001 | 0.01 |

| Congestive heart failure | 56,142 | 16.24 | 60,537 | 16.86 | <.0001 | 0.02 |

| Coronary artery disease | 98,868 | 28.60 | 101,725 | 28.33 | .010 | −0.01 |

| Stroke | 52,613 | 15.22 | 57,930 | 16.14 | <.0001 | 0.03 |

| Do not hospitalize | 9,788 | 2.83 | 9,191 | 2.56 | <.0001 | −0.02 |

| Do not resuscitate | 182,430 | 52.76 | 178,061 | 49.59 | <.0001 | −0.06 |

| Burrows behavior scale (1–10) (mean/SD) | 1.17 | (1.7) | 1.04 | (1.6) | <.0001 | −0.08 |

| ADL (1–28) (mean/SD) | 16.38 | 7.17 | 16.66 | 7.34 | <.0001 | 0.04 |

| Census characteristics of beneficiaries' zip code (mean/SD) | ||||||

| Median income | 50,471 | (17540.9) | 48,875 | (17532.1) | <.0001 | −0.09 |

| % Uninsured | 11.60 | (6.4) | 12.70 | (6.6) | <.0001 | 0.17 |

| % Public insurance | 33.44 | (9.4) | 34.71 | (9.6) | <.0001 | 0.13 |

| % Unemployed | 4.85 | (2.0) | 5.04 | (2.1) | <.0001 | 0.09 |

| % w/high school equivalence | 31.01 | (10.0) | 31.78 | (10.4) | <.0001 | 0.08 |

| % w/bachelor's degree | 18.10 | (8.0) | 16.93 | (8.1) | <.0001 | −0.15 |

| % ≥65 years old | 16.53 | (5.8) | 16.37 | (5.5) | <.0001 | −0.03 |

| % Living in a rural area | 18.32 | (27.6) | 23.59 | (31.6) | <.0001 | 0.18 |

ADL, activities of daily living; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HMO, health maintenance organization.

As a final check on our instrument, we conducted a falsification test in which we compared first‐stage results for individuals entering a nursing home far from the facility nearest to their primary residence. We base this falsification test on work done by Doyle (2011) in which he examined health care spending for individuals admitted to the emergency department while on vacation as a means of addressing selection due to geographic differences in health care spending. The decision to enter a nursing home far from home is often due to the proximity to family members, which suggests this decision should be unrelated to one's local exposure to a nursing home with an SCU. Thus, for individuals traveling far distances, we expect the first‐stage results to be small and nonsignificant.

In Figure S2, we present a figure identical to Figure 1 but stratified by the distance between the nearest nursing home to an individual and the nursing home to which they were admitted. In this figure, we can see that for individuals traveling far distances, differential distance has a weak relationship with the presence of an SCU in the admitting facility. Additionally, we find correlation coefficients measuring the linear association between differential distance and mean number of comorbidities between 0.0 and 0.02 for each absolute distance category, suggesting good balance in measured covariates across values of our instrument.

Distinguishing the Effect of the SCU from the Overall Quality of the Facility

The purported goal of SCUs is to provide better quality of care to patients with dementia (Luo et al. 2010). However, a common criticism is that instead of (or possibly in addition to) providing better care, SCUs are used as a marketing tool that signals to consumers the presence of a high‐quality facility that invests in their care (Phillips, Potter, and Simon 1998; Gruneir et al. 2007, 2008a, b). Indeed, within our own data we observe differences between SCU and non‐SCU facilities in the facility characteristics measured on the OSCAR survey and the characteristics of the local population as measure by the census (Table S1). In light of these criticisms and our own findings, it is important to consider if the benefits of admission to a nursing home with an SCU result from the SCU itself or if, instead, the SCU is a signal to consumers of facility quality. We focus on the distinction between the effect of the SCU and the effect of the facility in two ways. First, we replace our binary endogenous variable (SCU, yes or no) with a continuous measure of the proportion of SCU beds. We base this approach on the hypothesis that if SCUs directly affect quality of care, we would expect to observe a significant relationship between the proportion of SCU beds in a facility and quality of care outcomes, as a higher percentage of SCU beds implies a greater proportion of individuals “exposed” to the SCU. If, on the other hand, our estimates simply reflect overall facility quality, we would expect no relationship between proportion of SCU beds and quality of care outcomes.

As a second mechanism for distinguishing the role of the facility from that of the SCU, we expand the cohort to include individuals without dementia on admission and interact our instrument, differential distance, with a binary measure for dementia upon admission. Under this approach, we assume that the effect of a dementia SCU should be greatest among patients with dementia as they are the only patients eligible for admission to the SCU. Thus, if the difference between SCU and non‐SCU facilities reflected underlying quality, we would not expect to observe a difference in the effect of an SCU facility on patients with, as compared to without, dementia.

Results

Study Cohort

The study cohort consisted of 704,782 individuals, among whom the average age was 83.0 and 68.3 percent were female. Table 2 presents the characteristics of the study cohort overall and by the presence of an SCU in the facility to which they were admitted. Patients admitted to an SCU facility were more likely to be white (89.3 vs. 83.3 percent) and to have a do not resuscitate order (55.3 vs. 51.2 percent), and less likely to be dual eligible (26.1 vs. 31.0 percent) and to have mild cognitive impairment (19.1 vs. 22.6 percent) in addition to a higher Burrows Score value (1.3 vs. 1.0) and a lower score for activities of daily living (15.5 vs. 16.9). Additionally, patients in an SCU facility lived in zip codes with higher rates of uninsurance (12.6 vs. 11.1 percent), public insurance (34.5 vs. 33.1 percent) and unemployment (4.7 vs. 5.1 percent), and lower rates of bachelor's degrees (17.3 vs. 18.1).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Residents with Dementia Admitted to a Nursing Home Stratified by the Presence of a Dementia Special Care Unit (SCU) in the Nursing Home

| Overall | SCU | Non‐SCU | Standardized Mean Diff. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| N | 704,782 | – | 198,493 | 28% | 506,289 | 72% | – |

| Age (mean/SD) | 83.0 | (8.3) | 82.8 | (82.8) | 83.1 | (83.1) | −0.03 |

| Female | 481,419 | 68.3 | 133,268 | 67.1 | 348151 | 68.8 | −0.03 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 599,142 | 85.0 | 177,237 | 89.3 | 421,905 | 83.3 | 0.17 |

| Black | 75,605 | 10.7 | 15,504 | 7.8 | 60,101 | 11.9 | −0.14 |

| Married | 193,342 | 27.4 | 59,981 | 30.2 | 133,361 | 26.3 | 0.09 |

| Dual eligible | 218,510 | 31.0 | 51,820 | 26.1 | 166,690 | 32.9 | −0.15 |

| In an HMO | 106,125 | 15.1 | 30,965 | 15.6 | 75,160 | 14.9 | 0.02 |

| Hallucinations | 20,484 | 2.9 | 6,563 | 3.3 | 13,921 | 2.8 | 0.03 |

| Delusions | 40,402 | 5.7 | 14,366 | 7.2 | 26,036 | 5.1 | 0.09 |

| Bipolar | 12,282 | 1.7 | 3,378 | 1.7 | 8,904 | 1.8 | 0.00 |

| Schizophrenia | 14,378 | 2.0 | 3,323 | 1.7 | 11,055 | 2.2 | −0.04 |

| Anxiety | 106,893 | 15.2 | 31,170 | 15.7 | 75,723 | 15.0 | 0.02 |

| Cognitive impairment | |||||||

| Mild | 159,392 | 22.6 | 37,886 | 19.1 | 121,506 | 24.0 | −0.12 |

| Moderate | 425,928 | 60.4 | 127,222 | 64.1 | 298,706 | 59.0 | 0.10 |

| Severe | 119,341 | 16.9 | 33,352 | 16.8 | 85,989 | 17.0 | 0.00 |

| Depression | 261,861 | 37.2 | 76,450 | 38.5 | 185,411 | 36.6 | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 483,340 | 68.6 | 132,805 | 66.9 | 350,535 | 69.2 | −0.05 |

| Diabetes | 173,054 | 24.6 | 44,940 | 22.6 | 128,114 | 25.3 | −0.06 |

| COPD | 98,972 | 14.0 | 26,070 | 13.1 | 72,902 | 14.4 | −0.04 |

| Congestive heart failure | 116,679 | 16.6 | 29,460 | 14.8 | 87,219 | 17.2 | −0.07 |

| Coronary artery disease | 200,593 | 28.5 | 55,795 | 28.1 | 144,798 | 28.6 | −0.01 |

| Stroke | 110,543 | 15.7 | 26,373 | 13.3 | 84,170 | 16.6 | −0.09 |

| Do not hospitalize | 18,979 | 2.7 | 5,738 | 2.9 | 13,241 | 2.6 | 0.02 |

| Do not resuscitate | 360,491 | 51.2 | 109,742 | 55.3 | 250,749 | 49.5 | 0.12 |

| Burrows behavior scale (1–10) (mean/SD) | 1.1 | (1.6) | 1.3 | (1.7) | 1.0 | (1.6) | 0.16 |

| Activities of daily living score (1–28) (mean/SD) | 16.5 | (7.3) | 15.5 | (7.2) | 16.9 | (7.2) | −0.20 |

| Census characteristics of beneficiaries' zip code (mean/SD) | |||||||

| Median income | 49,658 | (17,555) | 50,704 | (50,704) | 49,248 | (49,248) | 0.08 |

| % Uninsured | 12.2 | (6.5) | 11.1 | (11.1) | 12.6 | (12.6) | −0.23 |

| % Public insurance | 34.1 | (9.5) | 33.1 | (33.1) | 34.5 | (34.5) | −0.14 |

| % Unemployed | 4.9 | (2.1) | 4.7 | (4.7) | 5.1 | (5.1) | −0.18 |

| % w/high school equivalence | 31.4 | (10.2) | 31.3 | (31.3) | 31.4 | (31.4) | −0.02 |

| % w/bachelor's degree | 17.5 | (8.0) | 18.1 | (18.1) | 17.3 | (17.3) | 0.11 |

| % ≥65 years old | 16.5 | (5.6) | 16.7 | (16.7) | 16.3 | (16.3) | 0.07 |

| % Living in a rural area | 21.0 | (21.0) | 19.0 | (19.0) | 21.8 | (21.8) | −0.09 |

ADL, activities of daily living; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HMO, health maintenance organization.

Primary Results

Table 3 presents the estimates of the effect of admission to a facility with an SCU on quality of care. Coefficient estimates represent the percentage point change in the quality of care measure associated with admission to a facility with an SCU. We present the results from both the linear probability and instrumental variable models. In the linear probability model, admission to a facility with an SCU is associated with a significant decrease in all measured outcomes with the exception of inappropriate antipsychotics and physical restraints.

Table 3.

Estimates of the Effect of Admission to a Facility with a Dementia Special Care Unit on Quality of Care for Patients with Dementia for (1) a Linear Probability Model and (2) Instrumental Variable Model. Estimates Are Interpreted Relative to the Mean of the Outcome. Coefficients Reflect Percentage Point Changes in the Outcome Associated with Admission to a Facility with a Dementia SCU (n = 5,257,524)

| Mean (%) | Linear Probability Model | Instrumental Variable Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. Evaluated at the Mean (%) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. Evaluated at the Mean (%) | ||

| Inappropriate antipsychotic use | 15.1 | 0.247 | 1.6 | −1.458*** | −9.7 |

| (0.155) | (0.331) | ||||

| Restraints | 7.0 | 0.0337 | 0.5 | −0.673** | −9.6 |

| (0.130) | (0.276) | ||||

| Pressure ulcer | 10.4 | −1.770*** | −17.0 | −0.344* | −3.3 |

| (0.0898) | (0.191) | ||||

| Catheter | 6.9 | −1.368*** | −19.8 | −0.0344 | −0.5 |

| (0.0726) | (0.174) | ||||

| Feeding tube | 4.6 | −1.429*** | −31.1 | −0.381* | −8.3 |

| (0.0896) | (0.196) | ||||

| Hospitalization | 12.3 | −1.499*** | −12.2 | −1.802*** | −14.7 |

| (0.0955) | (0.200) | ||||

Notes: All estimates are adjusted for covariates reported in Table 1, as well as state, year, and period fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the level of the facility (number of facilities = 15,743).

*p < .05, **p < .001, ***p < .001.

Coeff, coefficient; SCU, special care unit.

Similar to the linear probability model, estimates from the instrumental variable model also found significant decreases in the use of feeding tubes (coefficient −0.38, standard error 0.20), pressure ulcers (coefficient −0.34, standard error 0.19), and hospitalizations (coefficient 1.80, standard error 0.20), although no significant difference in the use of catheters. However, distinct from the linear probability model, the instrumental model found significant decrease in the use of inappropriate antipsychotics (coefficient −1.46, standard error 0.33) and the use of restraints (coefficient −0.67, 95% CI 0.28).

Additional Analyses

In Table 4, we present the results from two additional analyses aimed at distinguishing the effect of the SCU from the underlying quality of the facility within which it is embedded. First, we replaced the endogenous variable (SCU, yes or no) with a continuous measure of the proportion of beds in the facility that are dedicated SCU beds. Similar to results when using a binary instrument, we find a significant and negative relationship between the proportion of SCU beds in a facility and the risk of all outcomes with the exception of the use catheters.

Table 4.

Estimates of (1) the Effect of the Proportion of SCU Beds in a Nursing Home on Quality of Care for Patients with Dementia (n = 5,257,524) and (2) the Interaction Between Dementia on Admission and SCU (n = 10,399,082). Coefficients Reflect Percentage Point Changes in the Outcome

| (1) Proportion of SCU Beds | (2) Interaction Between Dementia and SCU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCU | Dementia | SCU × Dementia | ||

| Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | |

| Inappropriate antipsychotic use | −0.0630*** | −0.0617 | 8.357*** | −0.877*** |

| (0.0143) | (0.225) | (0.106) | (0.312) | |

| Restraints | −0.0291** | 0.670*** | 4.965*** | −1.659*** |

| (0.0120) | (0.157) | (0.0831) | (0.226) | |

| Pressure ulcer | −0.0148* | 2.033*** | −3.348*** | −2.331*** |

| (0.00824) | (0.260) | (0.0739) | (0.235) | |

| Catheter | −0.00148 | 2.505*** | −4.742*** | −2.956*** |

| (0.00750) | (0.267) | (0.0768) | (0.259) | |

| Feeding tube | −0.0165* | 0.828*** | −1.586*** | −1.732*** |

| (0.00848) | (0.244) | (0.0872) | (0.248) | |

| Hospitalization | −0.0779*** | −0.784*** | −4.140*** | −1.558*** |

| (0.00872) | (0.241) | (0.0640) | (0.202) | |

Notes: All estimates are adjusted for covariates reported in Table 1, as well as state, year, and period fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the level of the facility (number of facilities = 15,743).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Coeff, coefficient; SCU, special care unit.

Second, we expand the cohort to include nondementia patients and interact our endogenous measure for admission to a facility with an SCU in the second stage with a binary measure of dementia upon admission to the facility. Here we present the coefficients from the main effects (SCU and Dementia) as well as the interaction term. Across all quality measures, we find that there is a significantly greater negative effect of admission to a facility with an SCU for patients with, as compared to without, dementia.

Discussion

Numerous studies have evaluated the association between SCUs and quality of care for patients (Sloane et al. 1995; Reimer et al. 2004; Gruneir et al. 2007, 2008a, b; Cadigan et al. 2012). However, as Lai et al. (2009) highlighted in their Cochrane Report, nursing home selection is not exogenous. As a result, selection bias has been a frequent limitation in prior studies. This has ultimately resulted in mixed findings and confusion for both patients and policy makers as to the benefit of SCUs. In this study, we employ an instrumental variable approach to address this issue of selection, using differential distance to the nearest nursing home with and without an SCU to instrument for nursing home selection. Among residents with dementia admitted to a nursing home with an SCU, we found a significant reduction in the use of inappropriate antipsychotics, restraints, pressure ulcers, feeding tubes, and hospitalizations, but no change in the use of urinary indwelling catheters.

Differential distance instruments can be used for selection of a nursing home with or without an SCU, but they cannot distinguish between the direct effect of the SCU and other characteristics of nursing homes associated with the presence of an SCU that may also be associated with better quality of care. Thus, it is possible that our primary findings reflect higher quality facilities overall, and are not necessarily attributable to the SCU. This distinction between the effect of the SCU and the overall quality of the facility is important toward developing effective policy recommendations. Evidence that SCUs produce better outcomes would provide support for their expansion to additional nursing homes. However, evidence to the contrary would suggest that SCUs are, at best, a waste of valuable resources and, at worst, actually harming patients. Yet we find that as the proportion of SCU beds in a facility rises, the risk of inappropriate antipsychotic use, restraints, feeding tubes, pressure ulcers, and hospitalizations all decrease, suggesting that some, if not all, of the effect on quality of care operates through the SCU. These findings are further supported by the significant difference in the effect of admission to a facility with an SCU for patients with dementia as compared to those without dementia. It is important to note, however, that while the results from our additional analyses lend support to the hypothesis that there is a direct effect of the SCU on quality of care, we also find differences in the characteristics of facilities with and without an SCU. Thus, it is possible that both are true: facilities with SCUs tend to provide better quality overall, and the SCU also provides better quality care for patients with dementia.

Our study was limited in several ways. First, no single definition of an SCU exists, and the number of SCU beds is self‐reported. Thus, to the extent that the features of an SCU vary, what constitutes an SCU may vary by facility, although most SCUs do report specialized training for staff, lower staff‐to‐patient ratios, and physical environments tailored to dementia patients (Park‐Lee, Sengupta, and Harris‐Kojetin 2013). Given the lack of a standard definition, it is possible that the differences between SCU and non‐SCU facilities may not be as great as originally assumed, resulting in misclassification of our exposure. If this misclassification is nondifferential, meaning it is not associated with other facility characteristics that may affect quality of care, then our estimates may actually reflect an underestimate of the true effect. On the other hand, if the misclassification is associated with facility characteristics, then it is not possible to determine in which direction our estimates would be biased.

Second, the OSCAR survey is conducted approximately every 18 months, and a facility's SCU status may have changed during that period as SCUs were built or taken down. As a result, there is potential for misclassification of the instrument if the nearest identified SCU facility was actually a non‐SCU facility or vice versa. Of the 15,743 facilities in our sample, 1,744 (11.3 percent) of facilities either included or removed an SCU from their facility during the study period. However, this type of nondifferential misclassification would again serve to bias our estimates toward the null and result in an underestimate of the true effect. Lastly, although the MDS is a standard assessment tool for nursing homes, there have been reports of interfacility variation in the quality of reporting (Wu et al. 2005). Thus, it is possible that some facilities provided more accurate information on patients' health status and outcomes. However, no evidence exists that variation in the quality of data collection systematically favored SCU or non‐SCU facilities.

As the baby‐boom generation ages, the number of individuals with dementia will continue to rise and nursing homes will be charged with caring for a growing population with special treatment needs. Our findings suggest that SCUs are an effective method of reducing inappropriate antipsychotic use, physical restraints, feeding tubes, pressure ulcers, and hospitalizations. Our results are consistent when accounting for the percent of SCU beds in a facility and interactions between dementia and SCUs status, suggesting that our findings may not simply be the result of better quality of care overall but instead may be in part attributable to the SCU itself.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Figure S1: Example of Differential Distance (DD) Calculation between Nearest Nursing Home (NH) with and without a Dementia Special Care Unit (SCU).

Figure S2: Scatter Plots of the Adjusted Predicted Probability of Admission to a Facility with a Dementia SCU and Mean Number of Comorbidities by the Differential Distance to a Facility with versus without a Dementia SCU Stratified by the Absolute Distance Traveled to a Nursing Home A) >451 km (n = 142,210) B) 301 km to 450 km (n = 45,846) C) 151 km to 300 km (n = 60,713) D) <150 km (n = 5,008,755). Area of the Bubble Represents Relative Sample Size at Each Measure of Differential Distance Rounded to the Nearest 0.1 km.

Table S1: Facility Characteristics of Nursing Homes with and without an SCU in 2010.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: David Grabowski serves as a paid consultant to Precision Health Economics, Vivacitas, and CareLinx. Dr. Grabowski also serves on the Scientific Advisory Committee for NaviHealth. Nina Joyce has served as a paid consultant to Precision Health Economics during the period of data analysis, though she is not currently working as a consultant. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (1R01AG047194‐01A1). Nina Joyce's time was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH019733) and from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (5K12HS022998).

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimer: None.

References

- Alzheimer's Association . 2014. “2014 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures.” Alzheimer's & Dementia 10 (2): e47–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist, J. D. , and Imbens G. W.. 1995. “Two‐Stage Least Squares Estimation of Average Causal Effects in Models with Variable Treatment Intensity.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 90 (430): 431–42. [Google Scholar]

- Berlowitz, D. R. , Brandeis G. H., Anderson J., Du W., and Brand H.. 1997. “Effect of Pressure Ulcers on the Survival of Long‐Term Care Residents.” Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 52 (2): M106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M. , Duflo E., and Mullainathan S.. 2004. “How Much Should We Trust Differences‐in‐Differences Estimates?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (1): 249–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, J. M. , Irwin C. P., Hunsicker L. G., Flanigan M. J., Chrischilles E. A., and Pendergast J. F.. 2006. “Effect of Dialysis Center Profit‐Status on Patient Survival: A Comparison of Risk‐Adjustment and Instrumental Variable Approaches.” Health Services Research 41 (6): 2267–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, A. B. , Morris J. N., Simon S. E., Hirdes J. P., and Phillips C.. 2000. “Development of a Minimum Data Set‐Based Depression Rating Scale for Use in Nursing Homes.” Age and Ageing 29 (2): 165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan, R. O. , Grabowski D. C., Givens J. L., and Mitchell S. L.. 2012. “The Quality of Advanced Dementia Care in the Nursing Home: The Role of Special Care Units.” Medical Care 50 (10): 856–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J. J., Jr. 2011. “Returns to Local‐Area Healthcare Spending: Evidence from Health Shocks to Patients Far from Home.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3 (3): 221–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z. , Coots L. A., Kaganova Y., and Wiener J. M.. 2014. “Hospital and ED Use among Medicare Beneficiaries with Dementia Varies by Setting and Proximity to Death.” Health Affairs (Millwood) 33 (4): 683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foebel, A. D. , Onder G., Finne‐Soveri H., Lukas A., Denkinger M. D., Carfi A., Vetrano D. L., Brandi V., Bernabei R., and Liperoti R.. 2016. “Physical Restraint and Antipsychotic Medication Use among Nursing Home Residents with Dementia.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 17 (2): 184 e9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries, B. E. , Schneider D. P., Foley W. J., Gavazzi M., Burke R., and Cornelius E.. 1994. “Refining a Case‐mix Measure for Nursing Homes: Resource Utilization Groups (RUG‐III).” Medical Care 32 (7): 668–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadbois, E. A. , Tyler D. A., and Mor V.. 2017. “Selecting a Skilled Nursing Facility for Postacute Care: Individual and Family Perspectives.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 65 (11): 2459–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillick, M. R. 2000. “Rethinking the Role of Tube Feeding in Patients with Advanced Dementia.” New England Journal of Medicine 342 (3): 206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens, J. L. , Selby K., Goldfeld K. S., and Mitchell S. L.. 2012. “Hospital Transfers of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60 (5): 905–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneir, A. , Lapane K. L., Miller S. C., and Mor V.. 2007. “Long‐Term Care Market Competition and Nursing Home Dementia Special Care Units.” Medical Care 45 (8): 739–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneir, A. , Lapane K. L., Miller S. C., and Mor V.. 2008a. “Does the Presence of a Dementia Special Care Unit Improve Nursing Home Quality?” Journal of Aging and Health 20 (7): 837–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneir, A. , Lapane K. L., Miller S. C., and Mor V.. 2008b. “Is Dementia Special Care Really Special? A New Look at an Old Question.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56 (2): 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, L. G. , Larson E. H., and Lishner D. M.. 2005. “Rural Definitions for Health Policy and Research.” American Journal of Public Health 95 (7): 1149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmaier, S. L. , Sloane P. D., Guess H. A., and Koch G. G.. 1994. “The MDS Cognition Scale: A Valid Instrument for Identifying and Staging Nursing Home Residents with Dementia Using the Minimum Data set.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42 (11): 1173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirth, R. A. , Grabowski D. C., Feng Z., Rahman M., and Mor V.. 2014. “Effect of Nursing Home Ownership on Hospitalization of Long‐Stay Residents: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics 14 (1): 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd‐Leduc, J. M. , Sen S., Bertenthal D., Sands L. P., Palmer R. M., Kresevic D. M., Covinsky K. E., and Seth Landefeld C.. 2007. “The Relationship of Indwelling Urinary Catheters to Death, Length of Hospital Stay, Functional Decline, and Nursing Home Admission in Hospitalized Older Medical Patients.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 55 (2): 227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, S. , Rhodes R. L., Mitchell S. L., Mor V., and Teno J. M.. 2009. “Natural History of Feeding‐Tube Use in Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 10 (4): 264–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C. K. , Yeung J. H., Mok V., and Chi I.. 2009. “Special Care Units for Dementia Individuals with Behavioural Problems.” Cochrane Database Systematic Review (4): CD006470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, J. A. , Chakravarty S., Bowblis J. R., Gerhard T., Kalay E., Paek E. K., and Crystal S.. 2014. “Antipsychotic Medication Use in Nursing Homes: A Proposed Measure of Quality.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 29 (10): 1049–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H. , Fang X., Liao Y., Elliott A., and Zhang X.. 2010. “Associations of Special Care Units and Outcomes of Residents with Dementia: 2004 National Nursing Home Survey.” Gerontologist 50 (4): 509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan, M. , McNeil B. J., and Newhouse J. P.. 1994. “Does More Intensive Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Elderly Reduce Mortality? Analysis Using Instrumental Variables.” Journal of the American Medical Association 272 (11): 859–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S. L. , Morris J. N., Park P. S., and Fries B. E.. 2004. “Terminal Care for Persons with Advanced Dementia in the Nursing Home and Home Care Settings.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 7 (6): 808–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S. L. , Teno J. M., Miller S. C., and Mor V.. 2005. “A National Study of the Location of Death for Older Persons with Dementia.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53 (2): 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S. L. , Mor V., Gozalo P. L., Servadio J. L., and Teno J. M.. 2016. “Tube Feeding in US Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia, 2000–2014.” Journal of the American Medical Association 316 (7): 769–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. N. , Fries B. E., and Morris S. A.. 1999. “Scaling ADLs within the MDS.” Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 54 (11): M546–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. N. , Fries B. E., Mehr D. R., Hawes C., Phillips C., Mor V., and Lipsitz L. A.. 1994. “MDS Cognitive Performance Scale.” Journal of Gerontology 49 (4): M174–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.) . 2016. Long‐Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long‐Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Paksarian, D. , Cui L., Angst J., Ajdacic‐Gross V., Rössler W., and Merikangas K. R.. 2016. “Latent Trajectories of Common Mental Health Disorder Risk across Three Decades of Adulthood in a Population‐Based Cohort.” Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry 73 (10): 1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park‐Lee, E. , Sengupta M., and Harris‐Kojetin L. D.. 2013. “Dementia Special Care Units in Residential Care Communities: United States, 2010.” NCHS brief, number 143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C. D. , and Morris J. N.. 1997. “The Potential for Using Administrative and Clinical Data to Analyze Outcomes for the Cognitively Impaired: An Assessment of the Minimum Data Set for Nursing Homes.” Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 11 (suppl 6): 162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, V. L. , Potter S. J., and Simon S. L.. 1998. “Special Care Units for Alzheimer's Patients: Their Role in the Nursing Home Market.” Journal of Health and Human Services Administration 20 (3): 300–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Putten, M. J. G. , Wetzels R. B., Bor H., Zuidema S. U., and Koopmans R. T. C. M.. 2014. “Antipsychotic Drug Prescription Rates among Dutch Nursing Homes: The Influence of Patient Characteristics and the Dementia Special Care Unit.” Aging & Mental Health 18 (7): 828–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, M. A. , Slaughter S., Donaldson C., Currie G., and Eliasziw M.. 2004. “Special Care Facility Compared with Traditional Environments for Dementia Care: A Longitudinal Study of Quality of Life.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52 (7): 1085–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, G. A. , Shega J. W., and Cox‐Hayley D.. 2004. “Barriers to Excellent End‐of‐Life Care for Patients with Dementia.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 19 (10): 1057–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, D. , Kington R., Buchanan J., Bell R., Wang M., Lee M., Herbst M., Lee D., Sur D., and Rubenstein L.. 2000. “Appropriateness of the Decision to Transfer Nursing Facility Residents to the Hospital.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48 (2): 154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, P. D. , Lindeman D. A., Phillips C., Moritz D. J., and Koch G.. 1995. “Evaluating Alzheimer's Special Care Units: Reviewing the Evidence and Identifying Potential Sources of Study Bias.” Gerontologist 35 (1): 103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger, D. , and Stock J. H.. 1997. “Instrumental Variables Regression with Weak Instruments.” Econometrica 65 (3): 557–86. [Google Scholar]

- Teno, J. M. , Weitzen S., Wetle T., and Mor V.. 2001. “Persistent Pain in Nursing Home Residents.” Journal of the American Medical Association 285 (16): 2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, R. M. , Konetzka R. T., and Kim M. M.. 2013. “Quality Improvement under Nursing Home Compare: The Association between Changes in Process and Outcome Measures.” Medical Care 51 (7): 582–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N. , Miller S. C., Lapane K., Roy J., and Mor V.. 2005. “The Quality of the Quality Indicator of Pain Derived from the Minimum Data Set.” Health Services Research 40 (4): 1197–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, D. R. 2003. “Improving Nursing Home Quality of Care through Outcomes Data: The MDS Quality Indicators.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 18 (3): 250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Figure S1: Example of Differential Distance (DD) Calculation between Nearest Nursing Home (NH) with and without a Dementia Special Care Unit (SCU).

Figure S2: Scatter Plots of the Adjusted Predicted Probability of Admission to a Facility with a Dementia SCU and Mean Number of Comorbidities by the Differential Distance to a Facility with versus without a Dementia SCU Stratified by the Absolute Distance Traveled to a Nursing Home A) >451 km (n = 142,210) B) 301 km to 450 km (n = 45,846) C) 151 km to 300 km (n = 60,713) D) <150 km (n = 5,008,755). Area of the Bubble Represents Relative Sample Size at Each Measure of Differential Distance Rounded to the Nearest 0.1 km.

Table S1: Facility Characteristics of Nursing Homes with and without an SCU in 2010.