Abstract

Background

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is committed to providing high-quality care and addressing health disparities for vulnerable Veterans. To meet these goals, VA policymakers need guidance on how to address social determinants in operations planning and day-to-day clinical care for Veterans.

Method

MEDLINE (OVID), CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts were searched from inception to January 2017. Additional articles were suggested by peer reviewers and/or found through search of work associated with US and VA cohorts. Eligible articles compared Veterans vs non-Veterans, and/or Veterans engaged with those not engaged in VA healthcare. Our evidence maps summarized study characteristics, social determinant(s) addressed, and whether health behaviors, health services utilization, and/or health outcomes were examined. Qualitative syntheses and quality assessment were performed for articles on rurality, trauma exposure, and sexual orientation.

Results

We screened 7242 citations and found 131 eligible articles—99 compared Veterans vs non-Veterans, and 40 included engaged vs non-engaged Veterans. Most articles were cross-sectional and addressed socioeconomic factors (e.g., education and income). Fewer articles addressed rurality (N = 20), trauma exposure (N = 17), or sexual orientation (N = 2); none examined gender identity. We found no differences in rural residence between Veterans and non-Veterans, nor between engaged and non-engaged Veterans (moderate strength evidence). There was insufficient evidence for role of rurality in health behaviors, health services utilization, or health outcomes. Trauma exposures, including from events preceding military service, were more prevalent for Veterans vs non-Veterans and for engaged vs non-engaged Veterans (low-strength evidence); exposures were associated with smoking (low-strength evidence).

Discussion

Little published literature exists on some emerging social determinants. We found no differences in rural residence between our groups of interest, but trauma exposure was higher in Veterans (vs non-Veterans) and engaged (vs non-engaged). We recommend consistent measures for social determinants, clear conceptual frameworks, and analytic strategies that account for the complex relationships between social determinants and health.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4566-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: vulnerable populations, socioeconomic factors, population health

Introduction

Social determinants of health, especially those factors which define socioeconomic status (e.g., education and income), substantially influence health outcomes and healthcare utilization across the lifecourse, contributing to health disparities for disadvantaged groups.1–7 While acknowledging the importance of social determinants for population health, healthcare organizations and providers need guidance on how to assess and incorporate social determinants into policy, operations planning, and day-to-day clinical care.1, 8

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is committed to providing high-quality care and addressing disparities in health outcomes for vulnerable Veterans.9, 10 VHA Office of Patient Care Services—Population Health Services, and VHA Office of Rural Health (hereafter, VHA partners) requested an evidence review of social determinants of health for Veterans, to help develop policy for healthcare services which may be influenced by social determinants. Veterans enrolled in VHA services are more medically complex, have lower physical and mental health functioning, and have lower socioeconomic resources, as compared with either non-Veterans or Veterans not engaged in VHA care.11–13 Our VHA partners were especially interested in understanding whether certain social determinants may help explain differences in health outcomes between Veterans and non-Veterans, or between certain groups of Veterans (e.g., engaged or not engaged in VHA services).

Here, we present results from a larger evidence report14 prepared by the VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program (ESP) in response to our VHA partners, as noted above. We first developed evidence maps 15, 16 to describe the existing literature on how social determinants may contribute to differences in health behaviors, health services utilization, and health outcomes for Veterans vs non-Veterans, and Veterans engaged vs non-engaged in VHA care. We used these maps to engage our VHA partners in a prioritization process, leading to the selection of four high-priority social determinants for more detailed review and qualitative syntheses—rurality, trauma exposure, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

Methods

The protocol for this evidence review is registered at PROSPERO, no. CRD42017060165.17

Conceptual Frameworks and Key Questions

In collaboration with our VHA partners, we developed conceptual and analytic frameworks of the relationships between social determinants, Veteran experiences, health behaviors, health services utilization, and health outcomes (online Appendix Figure and14). We reviewed prior work from the MacArthur Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health18 and the Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine).1 We also considered whether particular social determinants were more likely relevant for Veterans’ health. We were primarily concerned with social determinants as mediators of the effects of Veteran experiences, but recognized at the outset that there may not be many studies which used appropriate analytic tests of mediation. Therefore, we planned to include articles that only compared prevalence, levels, and/or characteristics of social determinants between our groups of interest (e.g., Veterans vs. non-Veterans), as these may still indicate whether certain social determinants are particularly important for VHA policy and deserve further attention from VHA research. We developed the following key questions (KQ):

KQ1 and KQ2—For Veterans compared with non-Veterans, are there differences in prevalence and/or characteristics of social determinants (KQ1), and does such variation account for differences in health behaviors, health services utilization, and/or health outcomes (KQ2)?

KQ3 and KQ4—For engaged (i.e., enrolled in or utilizing categories of VHA services or benefits) compared with non-engaged Veterans, are there differences in prevalence and/or characteristics of social determinants (KQ3), and does such variation account for differences in health behaviors, health services utilization, and/or health outcomes (KQ4)?

Search Strategy and Article Selection

MEDLINE (OVID), CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts were searched from the date of inception to January 2017 (see online Appendix Table 1 and14 for detailed search strategies). We also included references (1) referred by expert peer reviewers; (2) associated with large national observational cohorts or cross-sectional surveys (e.g., American Community Survey); and (3) associated with large VA studies and programs (e.g., National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics). We considered gray literature (e.g., white papers and presentations), but found this did not add substantially to evidence from peer-reviewed, published articles; moreover, these sources frequently lacked sufficient information to assess quality. We also conducted a MEDLINE search with the same terms for Veterans and social determinants, but targeted to clinical trials instead of other study designs. We thought it unlikely that controlled clinical trials would address social determinants, but we carried out this additional search for completeness.

Citation/abstract screening was undertaken by 1–2 independent reviewers, with exclusion requiring consensus of both reviewers. Two independent reviewers conducted full-text review and discrepancies were resolved by discussion or referred to a third reviewer. Eligible English-language articles met the following criteria: (1) compared Veterans vs non-Veterans, and/or engaged vs non-engaged Veterans; (2) addressed at least one social determinant; (3) ≥ 100 participants; and (4) had eligible study design (e.g., cohort or cross-sectional study) (see Online Appendix Table 2 for detailed criteria). We also required valid comparison groups for social determinants (e.g., rural and non-rural participants); studies with only participants sharing a social determinant (e.g., all rural residents) were not considered as addressing comparisons for that social determinant.

We performed citation/abstract screening, full-text review, and data abstraction in DistillerSR, (https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/ accessed 5 July 2017).

Data Abstraction, Quality Assessment, and Qualitative Synthesis

Evidence maps: For all included articles (N = 131), we abstracted study design (e.g., cross-sectional or cohort); social determinants addressed; and whether analyses examined the role of social determinants in health behaviors, health services utilization, or health outcomes of interest.

Focused review and qualitative synthesis: For articles (N = 37) which investigated at least one of the four selected social determinants (i.e., rurality, trauma exposure, sexual orientation, and gender identity), we additionally abstracted data source(s); participant number and demographics; measure(s) of social determinant(s); the prevalence, degree, or level of social determinant(s) for the groups of interest (i.e., Veterans and non-Veterans, and/or engaged and non-engaged Veterans); and, if provided, the role of social determinants in health behaviors, health services utilization, and/or health outcomes. One reviewer completed data abstraction with verification by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers.

Two reviewers independently conducted quality assessments of included articles, with discrepancies resolved by discussion. We considered the following elements related to study quality:

Representativeness and coverage (i.e., nationally representative sample, recruitment and selection, and concerns about missing data)

Measurement (i.e., social determinants and outcomes assessed in similar manner for groups being compared and using standardized measures)

Funding source (i.e., potential for bias).

Given substantial heterogeneity of published articles and very limited evidence addressing these social determinants, quantitative synthesis was not appropriate. We rated overall strength of evidence as high, moderate, low, or insufficient, per Owens et al.19 We considered precision (degree of certainty in estimates), consistency (direction of differences across included articles), directness (whether evidence links social determinants directly to outcomes of interest), and individual article quality (as described above).

Results

Evidence Map

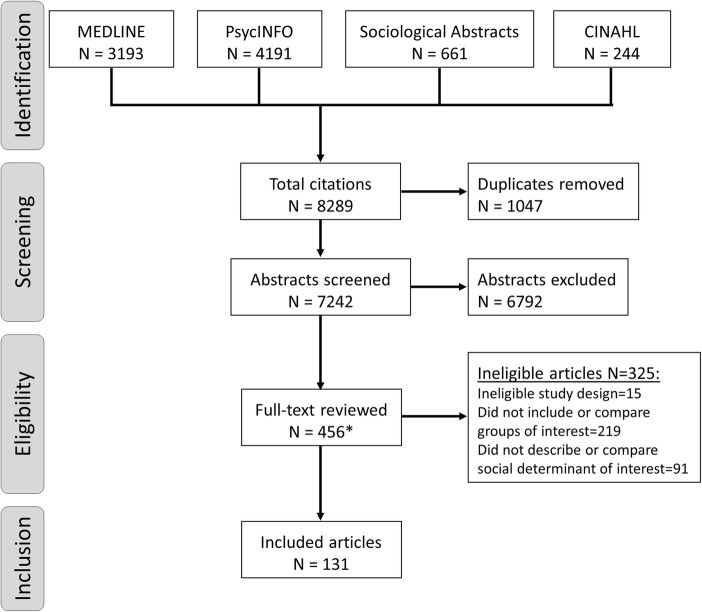

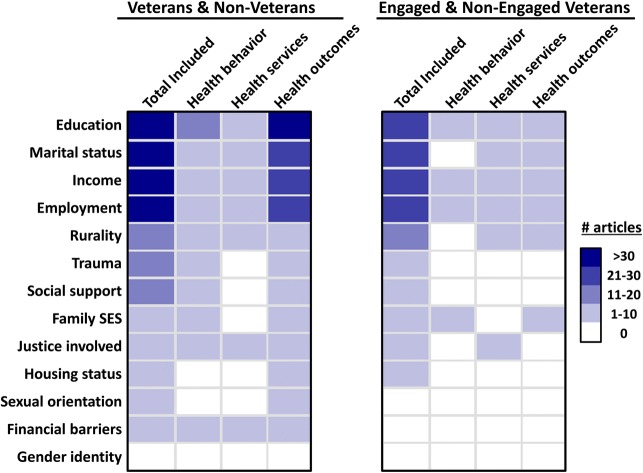

We screened 7242 abstracts, full-text reviewed 456 articles, and included 131 eligible articles (Fig. 1).20–150 Overall, most articles addressed classic socioeconomic factors, such as education, income, and employment; a substantial number of these articles examined the role of these factors in health outcomes, particularly for Veterans and non-Veterans, but fewer looked at health behaviors and health services utilization (Fig. 2, online Appendix Tables 3 and 4). For some social determinants, published evidence was lacking (e.g., sexual orientation and gender identity) (Fig. 2, online Appendix Tables 3 and 4). Ninety-nine articles addressed social determinants for Veterans and non-Veterans, and 40 articles for engaged and non-engaged Veterans. Most articles used cross-sectional data and included over 1000 participants (online Appendix Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

Citation screening and selection of included articles. Asterisk symbol indicates total articles reviewed includ an additional three articles found through an expedited review of MEDLINE citations (N = 354) identified using the same search terms except limited to trials, one article found through review of publications from the VA Epidemiology Program, and two articles recommended by expert reviewers.

Figure 2.

Heatmaps of included articles addressing social determinants and various outcomes for Veterans vs. non-Veterans, and for engaged vs. non-engaged Veterans. Articles may have addressed more than one social determinant, included comparisons of Veterans vs. non-Veterans and/or engaged vs. non-engaged Veterans, and may or may not have examined the role of social determinants in health behaviors, services access, and/or various health outcomes. Of 131 total included articles, 99 compared Veterans with non-Veterans, and 40 articles addressed engaged and non-engaged Veterans.

SES, socioeconomic status.

Qualitative Synthesis of Evidence on Rurality, Trauma, and Sexual Orientation

Twenty articles examined rurality, 17 addressed trauma, and 2 were on sexual orientation; no articles addressed gender identity. Most articles on rurality, trauma, and sexual orientation used nationally representative datasets, included more than 5000 participants, and were rated low or medium quality (Table 1). More than half of articles included only men or only women. Less than half of articles on rurality and trauma examined health behaviors, health services access or utilization, or health outcomes. One of two articles on sexual orientation addressed mortality risk.

Table 1.

Summary of Characteristics of Included Articles for Rurality and Trauma

| Veterans and non-Veterans | Engaged and non-engaged | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rurality | Trauma | Rurality | Trauma | |

| Total number of articles | 11 | 11 | 14 | 6 |

| Nationally representative dataset | 9 | 6 | 12 | 2 |

| Exclusively men | 5 | 2 | 2 | – |

| Exclusively women | – | 4 | – | 4 |

| Number of participants* | ||||

| 100–1000 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| 1001–5000 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| > 5000 | 6 | 6 | 9 | – |

| Quality | ||||

| Low | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Medium | 6 | 5 | 8 | 2 |

| High | 1 | 1 | 2 | – |

| Examined role of social determinant in | ||||

| Health behaviors | – | 5 | – | – |

| Health services access/utilization | 2 | – | 2 | – |

| Mental health | 3 | 3 | 1 | – |

| General health | 1 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Mortality | – | 1 | – | – |

| Other health outcomes | 1 | 1 | 1 | – |

Articles may have addressed more than one social determinant, and may or may not have examined the role of social determinants in health behaviors, health services access, and/or various health outcomes. There were also two included articles87, 89 on sexual orientation both compared Veterans and non-Veterans, using data from national cohorts, included only women, had more than 1000 participants, and were medium quality; one of these examined the role of sexual orientation on mortality and also addressed trauma exposure89

*Number of participants unclear in one article on rurality21

Rurality

We found moderate strength of evidence indicating no or very small differences in the proportion of Veterans and non-Veterans who reside in rural areas. Articles comparing Veterans with non-Veterans used different rurality measures, including Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA),21, 99, 106, 138, 140, 150 self-reported rural/urban residence,33, 70, 76 and Rural-Urban Continuum (RUC) codes137 (online Appendix Table 5). Most articles reported no differences in rural residence between Veterans and non-Veterans, although actual estimates varied widely (e.g., 18–47% of Veterans with rural or non-metropolitan residences). This was likely due to differences in rurality definition, participant demographics (e.g., age and sex), and study timeframes (range 1986–2012). Only one article reported higher rural residence in Veterans,84 and one found lower rurality in Veterans99; both were low quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Results Reported by Included Articles on Rurality, Trauma, and Sexual Orientation

| Number of articles reporting results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Results description | Veterans and non-Veterans | Engaged and non-engaged | |||

| Low quality | Medium or high quality | Low quality | Medium or high quality | |||

| Rurality | Prevalence | No difference* | 2 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Higher for Veterans/engaged | 1 | – | – | 1 | ||

| Higher for non-Veterans/non-engaged | 1 | – | 1 | 2 | ||

| Mixed or unclear results | – | 1 | – | 2 | ||

| Health behaviors | – | – | – | – | ||

| Health services utilization | Rurality associated with lower utilization | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Mixed or unclear results | – | 1 | – | 1 | ||

| Health outcomes | No association of rurality with general health | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| No association of rurality with mental health | – | 3 | – | 1 | ||

| No association of rurality with risk of hospitalization due to ambulatory care sensitive conditions | – | 1 | – | 1 | ||

| Trauma exposure | Prevalence | No difference* | 2 | – | – | 1 |

| Higher for Veterans/engaged | – | 4 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Higher for non-Veterans/non-engaged | 3 | 1 | – | – | ||

| Health behaviors | Trauma associated with more smoking | – | 3 | – | – | |

| Trauma associated with more heavy drinking | – | 2 | – | – | ||

| Unclear association with heavy drinking | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Unclear association with lack of exercise | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| No association with drug use | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Accounting for trauma reduced association of Veteran status with more smoking | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Health services utilization | – | – | – | – | ||

| Health outcomes | Trauma associated with more depression | – | 2 | – | – | |

| Trauma associated with worse general health, days of poor physical health, and days of poor mental health | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Accounting for trauma reduced association of Veteran status with greater disability | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Unclear association with mortality risk | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Sexual orientation | Prevalence | No difference* | – | 2 | – | – |

| Health behaviors | – | – | – | – | ||

| Health services utilization | – | – | – | – | ||

| Health outcomes | Sexual minority status associated with higher risk for all-cause mortality | – | 1 | – | – | |

Articles may have addressed more than one social determinant, and may or may not have examined the role of social determinants in health behaviors, health services access, and/or various health outcomes

*Non-significant difference or if no statistical testing, < 5% difference

We found insufficient evidence for the effects of rurality on differences in health behaviors, health services utilization, or health outcomes between Veterans and non-Veterans. While no articles examined the role of rurality in health behaviors, two medium-quality articles addressed utilization (Table 2). One article reported no differences between metropolitan and non-metropolitan participants in proportion having a “checkup” within the prior 2 years.137 The other article examined associations with total healthcare expenditures and found significant interaction effects between rural residence and a combined Veteran/VHA-user categorical variable (i.e., non-Veteran, Veteran VHA user, and Veteran non-VHA user); the magnitude of interaction effects was not reported.138 Three medium-quality articles investigated a variety of health outcomes,106, 137, 140 and none found significant associations for either Veteran status or rurality (Table 2).

We found moderate strength of evidence indicating no or very small differences in the proportion of engaged and non-engaged Veterans who reside in rural areas. Articles including engaged and non-engaged Veterans also employed varying measures of rurality, including MSA,21, 55, 138 self-reported rural/urban residence,70, 107, 120 RUC codes,81, 137 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes,26, 47, 48 and straight-line distances between participant homes and nearest VHA facility98 (online Appendix Table 6). More than half of articles reported no difference in rural residence between engaged and non-engaged Veterans (actual estimates 6–26%).47, 48, 55, 70, 73, 107, 120, 138 One medium-quality article found slightly higher rurality for engaged Veterans (30 vs 24% of non-engaged).137 In contrast, another medium-quality article reported lower rural residence in engaged Veterans (18% engaged vs 28% non-engaged), but was limited to Native Americans enrolled in VHA and Indian Health Service.81 One high-quality article used VHA administrative data and showed lower rural residence for Veterans using VHA homeless services (15% engaged vs 21% non-engaged).26

We found insufficient evidence for the effects of rurality on differences in health behaviors, health services utilization, or health outcomes between engaged and non-engaged Veterans. No articles examined health behaviors, but two medium-quality articles addressed utilization137, 138 (Table 2). Both of these articles defined engaged as self-reported VHA utilization, with one finding that rurality was associated with lower rate of check-ups137 and the other reporting significant interactions between rurality and Veteran/engaged status, as described above.138 Two medium-quality articles investigated health outcomes, and found no association between rurality and general or mental health,137 or with hospitalizations due to ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (21) (Table 2).

Trauma

We found low strength of evidence that there is a higher prevalence of trauma exposure among Veterans, as compared with non-Veterans. Articles comparing Veterans and non-Veterans used different measures to assess different trauma types (online Appendix Table 5). Six articles examined adverse childhood experiences29, 60, 77, 100, 103, 118, 145 and the Adverse Childhood Experiences scale (ACEs) was the most commonly used measure.29, 77, 100 All three articles using ACEs employed Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data, which included an ACEs module in multiple years. One article reported whether respondents had been “victimized” in the prior 12 months.139 Four articles examined adult experience of sexual trauma or intimate partner violence (IPV),34, 60, 103, 118 while two examined adult physical trauma.89, 103 Only one article examined combat-related trauma.103 Prevalence estimates were inconsistent across articles, with six finding higher prevalence among Veterans,29, 41, 77, 103, 118, 139 three finding lower prevalence among Veterans,34, 60, 89 and two finding no difference in prevalence between Veterans and non-Veterans.100, 145 Inconsistencies were likely due to a broad range of historical periods and cohorts being studied (i.e., Vietnam era through wars in Iraq and Afghanistan), and differences in age, sex, race/ethnicity, and other key participant characteristics (online Appendix Table 5). One article included only homeless smokers.60

There was low strength of evidence that trauma exposure contributes to differences in prevalence of smoking between Veterans and non-Veterans, and insufficient evidence for the role of trauma in health services utilization and health outcomes. Four articles examined associations of trauma exposure with health behaviors, and most focused on smoking and heavy drinking, which were self-reported in BRFSS.34, 41, 77, 100 Trauma exposure, whether IPV34, 41 or ACEs,77, 100 was associated with higher prevalence of current smoking (Table 2). Two of these articles also found a positive association between trauma exposure and heavy drinking.34, 77 One article analyzed trauma exposure as moderating the association between Veteran status and health behaviors (i.e., smoking and heavy drinking), finding significant interaction effects between Veteran status and ACEs score for smoking, but no significant interaction for predicting heavy drinking.77 One article showed that trauma exposure may mediate the association between Veteran status and smoking—higher odds of smoking for Veterans compared with non-Veterans (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.84 [95% CI 1.18, 2.88]) were reduced after including ACEs scores (AOR 1.57 [95% CI 0.96, 2.58]).100 Five articles34, 41, 77, 89, 100 examined a range of health outcomes, with two finding that trauma was positively associated with more depression,34, 41 and one showing associations with worse general health, more days of poor physical health, and more days of poor mental health77 (Table 2). One article showed that trauma partially mediated associations between Veteran status and disability—accounting for ACEs scores reduced the higher odds of disability among Veterans compared with non-Veterans (AOR 1.83 [95% CI 1.08, 3.10] without ACEs, and AOR 1.57 [95% CI 0.90, 2.75] with ACEs included).100 One article examined risk for all-cause mortality, cancer-specific mortality, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality, finding inconsistent associations between trauma and these outcomes, in models accounting for Veteran status.89

We found low strength of evidence that there is a higher prevalence of trauma exposure among engaged vs non-engaged Veterans. Articles on engaged and non-engaged Veterans also employed different measures and studied various trauma exposures (online Appendix Table 6). One article examined adverse childhood experiences and adult experience of sexual trauma or IPV,88 three articles addressed combat-related trauma and sexual or non-combat-related physical trauma during military service,88, 107, 115 one article examined history of military sexual assault,59 and one article examined Vietnam war-zone service.52 One article investigated military trauma related to sexual minority status.120 Estimates of trauma prevalence were primarily unadjusted and mostly consistent across articles, with five articles finding higher prevalence among engaged Veterans,52, 59, 88, 115, 120 and one showing mostly no difference.107

No articles examined the role of trauma in health behaviors, health services utilization, or health outcomes for engaged and non-engaged Veterans.

Sexual Orientation

We found insufficient evidence on sexual orientation for Veterans and non-Veterans, and no articles compared engaged and non-engaged Veterans (Table 2). The two articles examining sexual orientation for Veterans and non-Veterans both used nationally representative data, had only women participants, and were medium quality (online Appendix Table 5).87, 89 One article used National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (1999–2010) and reported no significant difference in prevalence of non-heterosexual orientation (7% Veterans vs 5% non-Veterans); no health behaviors, health services utilization, or health outcomes were examined.87 The other article used data from the Women’s Health Initiative and found more Veterans identified as sexual minorities (i.e., non-heterosexual) compared to non-Veterans (4 vs 1%).89 In adjusted analyses, sexual minority status and Veteran status were independently associated with increased risk for all-cause mortality.89 Interaction effects were also examined for sexual minority status and Veteran status, in predicting mortality risk but these were largely insignificant.89 These two articles differed in study populations (e.g., mean age 40 years87 vs 63 years89).

Discussion

In this evidence review of social determinants impacting health behaviors, health services utilization, and health outcomes for Veterans, we found that most published articles examined classic sociodemographic characteristics. A smaller set of published articles addressed factors, such as rurality and trauma. Few or no studies addressed the remaining group of emerging social determinants, including sexual orientation and gender identity. Often, even when there was substantial published literature for certain social determinants, gaps remained due to lack of studies examining how social determinants actually affected health behaviors, healthcare utilization, and/or health outcomes.

We found little to no evidence on the roles of rurality and trauma exposure on health behaviors, health services utilization, and health outcomes, whether comparing Veterans vs non-Veterans or engaged vs non-engaged Veterans. Given this lack of evidence, existing literature on the impact of these factors in the general population can help guide policy for Veterans. Numerous challenges and health disparities affecting rural US communities have been demonstrated151; Veterans in rural settings likely face similar resource limitations, access barriers, and risk factors. Similarly, there are substantial health consequences of trauma exposures for the general adult population,152 which should inform policy and planning for Veterans. For example, VHA could improve standardized assessment for exposures, develop strategies for providing trauma-sensitive care, and consider targeted efforts to prevent negative impacts associated with poor health behaviors (e.g., smoking). Since some types of trauma exposure precede military service, it may also be beneficial to develop assessment and strategies at the time of enlistment.

We found insufficient evidence for both sexual orientation and gender identity. Challenges to addressing these factors include cultural stigma and lack of standardized assessment in many current national datasets.

The VHA Blueprint for Excellence153 outlines several essential strategies for improving services and enhancing Veteran health, including addressing the needs of vulnerable Veterans and delivering personalized, patient-centered care (e.g., considering relevant social determinants). Our review supports systematic assessment for socioeconomic factors which have a robust literature and contribute to health disparities.1, 7 For social determinants with more limited evidence specifically for Veterans, such as rurality and trauma exposure, we suggest that current evidence gaps should not preclude the development of VHA policies to address probable challenges and health impacts of these factors for Veterans. For social determinants with little to no evidence, such as sexual orientation and gender identity, VHA should support development of consistent, accurate measures within VHA, and advocate for inclusion of these measures in ongoing large national surveys on health and behavior. Integration of VHA data with existing non-VHA data sources could also help us compare the impact of social determinants on Veterans engaged and not engaged in VHA services.

Our review highlights certain challenges in examining the role of social determinants in health. First, measures for rurality and trauma exposure often encompassed conceptually related but distinct aspects within these broader constructs. Rural communities are defined not just by distance and population density, but also by social connections, cultural norms, and attitudes.154 To address health disparities for rural Veterans, we need direct measures of those aspects relevant to health. Similarly, although a variety of adverse circumstances and traumatic events could plausibly affect Veterans’ health, failing to make conceptually important distinctions in types of trauma leads to challenges in defining those key relationships that could be targeted to improve health outcomes. Second, per our conceptual model (online Appendix Figure), relationships involving social determinants are likely bidirectional and dynamic over the lifespan. For example, education can affect selection into the military, and military service could in turn impact educational attainment (e.g., military training or as benefits for Veterans).155 In the current era of service without conscription, social determinants may have even stronger effects on selection into the military and the nature of military experiences. One article highlighted this complexity by showing that for men in the current era, there was greater childhood adversity for Veterans compared with non-Veterans, but this was not true when comparing men who would have served during the draft era.29 Future studies should address selection effects of social determinants and other mechanisms that predate military service.

Our evidence review has several limitations. We excluded articles if they did not compare our populations of interest; thus, our results do not imply that evidence did not exist for the general population. Publication bias may have affected our results if articles were less likely to be published when results showed no impact of social determinants on health. Finally, although we aimed to be broad and inclusive in conducting our review, our final search and selection focused on social determinants of high interest to our VHA partners.

In conclusion, we found limited to no evidence on certain emerging social determinants. We found no differences in rural residence between our groups of interest; trauma exposure was higher in Veterans (vs non-Veterans) and Veterans engaged in VHA care (vs non-engaged). We found insufficient evidence on sexual orientation and gender identity. We recommend consistent measures for social determinants, clear conceptual frameworks, and analytic strategies that account for the complex relationships between social determinants, Veteran experiences, and health.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 62 kb)

Funders

This work was supported by VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) funding for ESP (VA-ESP Project No.09-009; 2017). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit article for publication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

Results from this evidence review were presented as a poster at the national VA Health Services Research & Development/QUERI meeting in July 2017.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: phase 2. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed]

- 2.Tarlov AR. Public policy frameworks for improving population health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896(1):281–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot MG, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Inequalities in death—specific explanations of a general pattern? The Lancet. 1984;323(8384):1003–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)92337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot MG, Stansfeld S, Patel C, North F, Head J, White I, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. The Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1387–93. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of health and social behavior. 2010;51(1_suppl):S28–S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1186:5–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler NE, Glymour MM, Fielding J. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1641–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Washington AE, Coye MJ, Boulware LE. Academic health systems’ third curve: population health improvement. JAMA. 2016;315(5):459–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VHA Office of Health Equity. https://www.va.gov/healthequity/. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- 10.VHA Patient care services—LGBT care. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/LGBT/. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- 11.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, Cong Z, Rogers W, Haffer SC, et al. The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1271–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Use of the internet and an online personal health record system by US veterans: comparison of Veterans Affairs mental health service users and other veterans nationally. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(6):1089–94. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duan-Porter W, Martinson BC, Taylor BC, Falde S, Gnan K, Greer N, et al. ESP evidence review: social determinants of health for veterans. 2017. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/socialdeterminants.cfm. Accessed June 7, 2018. [PubMed]

- 15.Bragge P, Clavisi O, Turner T, Tavender E, Collie A, Gruen RL. The Global Evidence Mapping Initiative: scoping research in broad topic areas. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;11:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan RE, Kaufman CA, Hill SJ. Building blocks for meta-synthesis: data integration tables for summarising, mapping, and synthesising evidence on interventions for communicating with health consumers. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Social determinants of health for Veterans—PROSPERO protocol. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=60165. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- 18.MacArthur Research Network on SES & Health. http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- 19.Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, Treadwell JR, Reston JT, Bass EB, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Effective Health-Care Program. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(5):513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham Kristen M., Ganoczy Dara, Yosef Matheos, Resnick Sandra G., Zivin Kara. Receipt of employment services among Veterans Health Administration users with psychiatric diagnoses. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2014;51(3):401–414. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2013.05.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajmera Mayank, Wilkins Tricia Lee, Sambamoorthi Usha. Dual Medicare and Veteran Health Administration Use and Ambulatory Care Sensitive Hospitalizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(S2):669–675. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1788-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin Carol M., Long Kathi, Kroesen Kendall, Brooks Audrey J., Bell Iris R. A Profile of Military Veterans in the Southwestern United States Who Use Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(15):1697. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bareis N, Mezuk, Briana. The relationship between childhood poverty, military service, and later life depression among men: evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Barrera Terri L., Cully Jeffrey A., Amspoker Amber B., Wilson Nancy L., Kraus-Schuman Cynthia, Wagener Paula D., Calleo Jessica S., Teng Ellen J., Rhoades Howard M., Masozera Nicholas, Kunik Mark E., Stanley Melinda A. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for late-life anxiety: Similarities and differences between Veteran and community participants. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;33:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastian Lori A., Gray Kristen E., DeRycke Eric, Mirza Shireen, Gierisch Jennifer M., Haskell Sally G., Magruder Kathryn M., Wakelee Heather A., Wang Ange, Ho Gloria Y. F., LaCroix Andrea Z. Differences in Active and Passive Smoking Exposures and Lung Cancer Incidence Between Veterans and Non-Veterans in the Women’s Health Initiative. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S102–S111. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blackstock Oni J., Haskell Sally G., Brandt Cynthia A., Desai Rani A. Gender and the Use of Veterans Health Administration Homeless Services Programs Among Iraq/Afghanistan Veterans. Medical Care. 2012;50(4):347–352. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blosnich John, Foynes Melissa Ming, Shipherd Jillian C. Health Disparities Among Sexual Minority Women Veterans. Journal of Women's Health. 2013;22(7):631–636. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blosnich J, Bossarte, R.,Silver, E.,Silenzio, V. Health care utilization and health indicators among a national sample of U.S. veterans in same-sex partnerships. Military Medicine. 2013;178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Blosnich John R., Dichter Melissa E., Cerulli Catherine, Batten Sonja V., Bossarte Robert M. Disparities in Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Individuals With a History of Military Service. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1041. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohnert Amy S.B., Ilgen Mark A., Bossarte Robert M., Britton Peter C., Chermack Stephen T., Blow Frederic C. Veteran Status and Alcohol Use in Men in the United States. Military Medicine. 2012;177(2):198–203. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bookwala Jamila, Frieze Irene, Grote Nancy. The Long-Term Effects of Military Service on Quality of Life: The Vietnam Experience1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;24(6):529–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00597.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boscarino Joseph A., Sitarik Alexandra, Gordon Stuart C., Rupp Loralee B., Nerenz David R., Vijayadeva Vinutha, Schmidt Mark A., Henkle Emily, Lu Mei. Risk Factors for Hepatitis C Infection Among Vietnam Era Veterans Versus Nonveterans: Results from the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS) Journal of Community Health. 2014;39(5):914–921. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9863-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown Christian, Routon P. Wesley. Military Service and the Civilian Labor Force. Armed Forces & Society. 2016;42(3):562–584. doi: 10.1177/0095327X15625499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerulli C, Bossarte, Robert M., Dichter, Melissa E. Exploring intimate partner violence status among male veterans and associated health outcomes. American Journal of Men's Health. 2014;8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Chi Ru-Chien, Reiber Gayle E., Neuzil Kathleen M. Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination in Older Veterans: Results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54(2):217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordray Sheila M., Polk Kenneth R., Britton Brandy M. Premilitary antecedents of post-traumatic stress disorder in an oregon cohort. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1992;48(3):271–280. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199205)48:3<271::AID-JCLP2270480302>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cowper Diane C., Longino Charles F., Kubal Joseph D., Manheim Larry M., Dienstfrey Stephen J., Palmer Jill M. The Retirement Migration of U.S. Veterans, 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19(2):123–137. doi: 10.1177/073346480001900201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culp Richard, Youstin Tasha J., Englander Kristin, Lynch James. From War to Prison: Examining the Relationship Between Military Service and Criminal Activity. Justice Quarterly. 2013;30(4):651–680. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2011.615755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Currier Joseph M., McDermott Ryon C., Sims Brook M. Patterns of help-seeking in a national sample of student veterans: a matched control group investigation. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2016;43:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Luca SM, Blosnich, John R., Hentschel, Elizabeth A. W., King, Erika, Amen, Sally. Mental health care utilization: how race, ethnicity and veteran status are associated with seeking help. Community Mental Health Journal. 2016;52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Dichter Melissa E., Cerulli Catherine, Bossarte Robert M. Intimate Partner Violence Victimization Among Women Veterans and Associated Heart Health Risks. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21(4):S190–S194. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunne Eugene M., Burrell Larry E., Diggins Allyson D., Whitehead Nicole Ennis, Latimer William W. Increased risk for substance use and health-related problems among homeless veterans. The American Journal on Addictions. 2015;24(7):676–680. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dursa Erin K., Barth Shannon K., Bossarte Robert M., Schneiderman Aaron I. Demographic, Military, and Health Characteristics of VA Health Care Users and Nonusers Who Served in or During Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2009-2011. Public Health Reports. 2016;131(6):839–843. doi: 10.1177/0033354916676279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elder GH, Jr.,Shanahan, M. J.,Clipp, E. C. When war comes to men’s lives: life-course patterns in family, work, and health. Psychology & Aging. 1994;9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.ELHAI JON D., FRUEH B. CHRISTOPHER, GOLD PAUL B., GOLD STEVEN N., HAMNER MARK B. Clinical Presentations of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder across Trauma Populations. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188(10):708–713. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200010000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faestel PM, Littell, C. T.,Vitiello, M. V.,Forsberg, C. W.,Littman, A. J. Perceived insufficient rest or sleep among veterans: behavioral risk factor surveillance system 2009. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2013;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.French Dustin D., Margo Curtis E. Factors Associated With the Utilization of Cataract Surgery for Veterans Dually Enrolled in Medicare. Military Medicine. 2012;177(6):752–756. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.French DD, Bradham, Douglas D., Campbell, Robert R., Haggstrom, David A., Myers, Laura J., Chumbler, Neale R., Hagan, Michael P. Factors associated with program utilization of radiation therapy treatment for VHA and medicare dually enrolled patients. Journal of Community Health: The Publication for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. 2012;37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Fulton Lawrence V., Belote Janna M., Brooks Matthew S., Coppola M. Nicholas. A Comparison of Disabled Veteran and Nonveteran Income. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2009;20(3):184–191. doi: 10.1177/1044207309341359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabrielian Sonya, Yuan Anita H., Andersen Ronald M., Rubenstein Lisa V., Gelberg Lillian. VA Health Service Utilization for Homeless and Low-income Veterans. Medical Care. 2014;52(5):454–461. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gabrielian Sonya, Burns Alaina V., Nanda Nupur, Hellemann Gerhard, Kane Vincent, Young Alexander S. Factors Associated With Premature Exits From Supported Housing. Psychiatric Services. 2016;67(1):86–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gamache Gail, Rosenheck Robert A., Tessler Richard. Factors Predicting Choice of Provider Among Homeless Veterans With Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(8):1024–1028. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.8.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gamache G., Rosenheck R., Tessler R. The proportion of veterans among homeless men: a decade later. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001;36(10):481–485. doi: 10.1007/s001270170012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gfeller Jeffrey D., Roskos P. Tyler. A Comparison of Insufficient Effort Rates, Neuropsychological Functioning, and Neuropsychiatric Symptom Reporting in Military Veterans and Civilians with Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2013;31(6):833–849. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gorman Lisa A., Sripada Rebecca K., Ganoczy Dara, Walters Heather M., Bohnert Kipling M., Dalack Gregory W., Valenstein Marcia. Determinants of National Guard Mental Health Service Utilization in VA versus Non-VA Settings. Health Services Research. 2016;51(5):1814–1837. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gould CE, Rideaux, Tiffany, Spira, Adam P., Beaudreau, Sherry A. Depression and anxiety symptoms in male veterans and non?veterans: the Health and Retirement study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck, Robert A, Desai, Rani A. Risk of incarceration among male Veterans and Nonveterans: are Veterans of the All Volunteer Force at greater risk? Armed Forces & Society. 2007;33.

- 58.Grossbard Joel R., Lehavot Keren, Hoerster Katherine D., Jakupcak Matthew, Seal Karen H., Simpson Tracy L. Relationships Among Veteran Status, Gender, and Key Health Indicators in a National Young Adult Sample. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64(6):547–553. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.003002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamilton Alison B., Frayne Susan M., Cordasco Kristina M., Washington Donna L. Factors Related to Attrition from VA Healthcare Use: Findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(S2):510–516. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2347-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hammett Patrick, Fu Steven S., Lando Harry A., Owen Greg, Okuyemi Kolawale S. The association of military discharge variables with smoking status among homeless Veterans. Preventive Medicine. 2015;81:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardy Melissa A., Reyes Adriana M. The Longevity Legacy of World War II: The Intersection of GI Status and Mortality. The Gerontologist. 2015;56(1):104–114. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartley TA, Violanti, J. M.,Mnatsakanova, A.,Andrew, M. E.,Burchfiel, C. M. Military experience and levels of stress and coping in police officers. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2013;15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Hedrick Brad, Pape Theresa Louise-Bender, Heinemann Allen W., Ruddell Jennifer L., Reis Janet. Employment issues and assistive technology use for persons with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2006;43(2):185. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2005.03.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Henderson C, Bainbridge, Jay, Keaton, Kim, Kenton, Martha, Guz, Meghan, Kanis, Becky. The use of data to assist in the design of a new service system for homeless veterans in New York City. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2008;79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Heslin KC, Guerrero, E. G.,Mitchell, M. N.,Afable, M. K.,Dobalian, A. Explaining differences in hepatitis C between U.S. veterans and nonveterans in treatment for substance abuse: results from a regression decomposition. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.HISNANICK JOHN J. Changes over Time in the ADL Status of Elderly US Veterans. Age and Ageing. 1994;23(6):505–511. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.6.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoerster Katherine D., Lehavot Keren, Simpson Tracy, McFall Miles, Reiber Gayle, Nelson Karin M. Health and Health Behavior Differences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(5):483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoff Rani A., Rosenheck Robert A. The Use of VA and Non-VA Mental Health Services by Female Veterans. Medical Care. 1998;36(11):1524–1533. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoglund Mark W., Schwartz Rebecca M. Mental Health in Deployed and Nondeployed Veteran Men and Women in Comparison With Their Civilian Counterparts. Military Medicine. 2014;179(1):19–25. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Houston TK, Volkman, Julie E., Feng, Hua, Nazi, Kim M., Shimada, Stephanie L., Fox, Susannah. Veteran Internet use and engagement with health information online. Military Medicine. 2013;178. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Howren M. Bryant, Cai Xueya, Rosenthal Gary, Vander Weg Mark W. Associations of Health-Related Quality of Life with Healthcare Utilization Status in Veterans. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2011;7(1):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s11482-011-9147-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoy-Ellis Charles P., Shiu Chengshi, Sullivan Kathleen M., Kim Hyun-Jun, Sturges Allison M., Fredriksen-Goldsen Karen I. Prior Military Service, Identity Stigma, and Mental Health Among Transgender Older Adults. The Gerontologist. 2017;57(suppl 1):S63–S71. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hynes Denise M., Koelling Kristin, Stroupe Kevin, Arnold Noreen, Mallin Katherine, Sohn Min-Woong, Weaver Frances M., Manheim Larry, Kok Linda. Veterans??? Access to and Use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs Health Care. Medical Care. 2007;45(3):214–223. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244657.90074.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johnson Anna M., Rose Kathryn M., Elder Jr. Glen H., Chambless Lloyd E., Kaufman Jay S., Heiss Gerardo. Military combat and burden of subclinical atherosclerosis in middle aged men: The ARIC Study. Preventive Medicine. 2010;50(5-6):277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson Anna M., Rose Kathryn M., Elder Glen H., Chambless Lloyd E., Kaufman Jay S., Heiss Gerardo. Military Combat and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Ischemic Stroke in Aging Men: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20(2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaplan MS, Huguet, Nathalie, McFarland, Bentson H., Newsom, Jason T. Suicide among male veterans: a prospective population-based study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Katon J LK, Simpson T, Williams E, Barnett S, Grossbard J, Schure M, Gray K, Reiber G. Adverse childhood experiences, military. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Kleykamp Meredith. Unemployment, earnings and enrollment among post 9/11 veterans. Social Science Research. 2013;42(3):836–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koepsell T. Behavioral Risk Factors and Use of Preventive Services among Veterans in Washington State. Preventive Medicine. 2002;35(6):557–562. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koepsell Thomas D., Littman Alyson J., Forsberg Christopher W. Obesity, Overweight, and Their Life Course Trajectories in Veterans and Non-Veterans. Obesity. 2011;20(2):434–439. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kramer B Josea, Wang Mingming, Jouldjian Stella, Lee Martin L., Finke Bruce, Saliba Debra. Veterans Health Administration and Indian Health Service. Medical Care. 2009;47(6):670–676. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195fa5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kramer B. Josea, Jouldjian Stella, Wang Mingming, Dang Jeff, Mitchell Michael N., Finke Bruce, Saliba Debra. Do Correlates of Dual Use by American Indian and Alaska Native Veterans Operate Uniformly Across the Veterans Health Administration and the Indian Health Service? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(S2):662–668. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1834-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.LaCroix Andrea Z., Rillamas-Sun Eileen, Woods Nancy F., Weitlauf Julie, Zaslavsky Oleg, Shih Regina, LaMonte Michael J., Bird Chloe, Yano Elizabeth M., LeBoff Meryl, Washington Donna, Reiber Gayle. Aging Well Among Women Veterans Compared With Non-Veterans in the Women’s Health Initiative. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S14–S26. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Laudet Alexandre, Timko Christine, Hill Thomas. Comparing Life Experiences in Active Addiction and Recovery Between Veterans and Non-Veterans: A National Study. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2014;33(2):148–162. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.909702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.LaVela S.L., Prohaska T.R., Furner S., Weaver F.M. Preventive healthcare use among males with multiple sclerosis. Public Health. 2012;126(10):896–903. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lehavot Keren, Hoerster Katherine D., Nelson Karin M., Jakupcak Matthew, Simpson Tracy L. Health Indicators for Military, Veteran, and Civilian Women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(5):473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lehavot Keren, Katon Jodie G., Williams Emily C., Nelson Karin M., Gardella Carolyn M., Reiber Gayle E., Simpson Tracy L. Sexual Behaviors and Sexually Transmitted Infections in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women Veterans and Nonveterans. Journal of Women's Health. 2014;23(3):246–252. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lehavot Keren, O'Hara Ruth, Washington Donna L., Yano Elizabeth M., Simpson Tracy L. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Severity and Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Veterans Health Administration Use among Women Veterans. Women's Health Issues. 2015;25(5):535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lehavot Keren, Rillamas-Sun Eileen, Weitlauf Julie, Kimerling Rachel, Wallace Robert B., Sadler Anne G., Woods Nancy Fugate, Shipherd Jillian C., Mattocks Kristin, Cirillo Dominic J., Stefanick Marcia L., Simpson Tracy L. Mortality in Postmenopausal Women by Sexual Orientation and Veteran Status. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S150–S162. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Little Roger D., Fredland J. Eric. Veteran Status, Earnings, and Race. Armed Forces & Society. 1979;5(2):244–260. doi: 10.1177/0095327X7900500203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.London Andrew S., Heflin Colleen M., Wilmoth Janet M. Work-Related Disability, Veteran Status, and Poverty: Implications for Family Well-Being. Journal of Poverty. 2011;15(3):330–349. doi: 10.1080/10875549.2011.589259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Long Judith A., Polsky Daniel, Asch David A. Receipt of Health Services by Low-Income Veterans. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2003;14(3):305–317. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lopreato SC, Poston, Dudley L, Jr. Differences in earnings and earnings ability between Black Veterans and nonveterans in the United States. Social Science Quarterly. 1977;57.

- 94.MacLean Alair. Lessons from the Cold War: Military Service and College Education. Sociology of Education. 2005;78(3):250–266. doi: 10.1177/003804070507800304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MacLean Alair, Kleykamp Meredith. Income Inequality and the Veteran Experience. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2015;663(1):99–116. doi: 10.1177/0002716215596964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marrie Ruth Ann, Cutter Gary, Tyry Tuula, Campagnolo Denise, Vollmer Timothy. Differences in Bladder Care for Veterans with Multiple Sclerosis by Treatment Location. International Journal of MS Care. 2009;11(2):91–97. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073-11.2.91. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martindale Melanie, Poston Dudley L. Variations in Veteran/Nonveteran Earnings Patterns Among World War II, Korea, and Vietnam War Cohorts. Armed Forces & Society. 1979;5(2):219–243. doi: 10.1177/0095327X7900500202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McCarthy JF, Valenstein, Marcia, Dixon, Lisa, Visnic, Stephanie,Blow, Frederic C., Slade, Eric. Initiation of assertive community treatment among veterans with serious mental illness: client and program factors. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.McCaskill GM, Sawyer, P.,Burgio, K. L.,Kennedy, R.,Williams, C. P.,Clay, O. J.,Brown, C. J.,Allman, R. M. The impact of Veteran status on life-space mobility among Older Black and White men in the Deep South. Ethnicity & Disease. 2015;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.McCauley HL, Blosnich, John R., Dichter, Melissa E. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health outcomes among veteran and non-veteran women. Journal of Women's Health. 2015;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.McLay Robert N., Lyketsos Constantine G. Veterans Have Less Age-Related Cognitive Decline. Military Medicine. 2000;165(8):622–625. doi: 10.1093/milmed/165.8.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Murdoch M, Sayer, Nina A., Spoont, Michele R., Rosenheck, Robert, Noorbaloochi, Siamak, Griffin, Joan M., Arbisi, Paul A., Hagel, Emily M. Long-term outcomes of disability benefits in US veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Naifeh JA, North, Terry C., Davis, Joanne L., Reyes, Gilbert, Logan, Constance A., Elhai, Jon D. Clinical profile differences between PTSD-diagnosed military veterans and crime victims. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2008;9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Nelson Karin M. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(9):915–919. doi: 10.1007/BF02743137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nyamathi A, Sands, Heather, Pattatucci-Aragón, Angela, Berg, Jill, Leake, Barbara, Hahn, Joan Earle, Morisky, Donald. Perception of health status by homeless US Veterans. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance. 2004;27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 106.O'Donnell John C. Military Service and Mental Health in Later Life. Military Medicine. 2000;165(3):219–223. doi: 10.1093/milmed/165.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ouimette Paige, Wolfe Jessica, Daley Jennifer, Gima Kristian. Use of VA Health Care Services by Women Veterans: Findings from a National Sample. Women & Health. 2003;38(2):77–91. doi: 10.1300/J013v38n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Padula CB, PhD, Weitlauf, Julie C, PhD, Rosen, Allyson C, PhD, ABPP-CN, Reiber, Gayle, PhD, MPH, Cochrane, Barbara B, PhD, RN, Naughton, Michelle J, PhD, Li, Wenjun, PhD, Rissling, Michelle, PhD, Yaffe, Kristine, MD, Hunt, Julie R, PhD, Stefanick, Marcia L, PhD, Goldstein, Mary K, MD, MS, Espeland, Mark A, PhD. Longitudinal cognitive trajectories of Women Veterans from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. The Gerontologist. 2016;56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 109.Petrovich James C., Pollio David E., North Carol S. Characteristics and Service Use of Homeless Veterans and Nonveterans Residing in a Low-Demand Emergency Shelter. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(6):751–757. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Phillips Barbara R., Shahoumian Troy A., Backus Lisa I. Surveyed Enrollees in Veterans Affairs Health Care: How They Differ From Eligible Veterans Surveyed by BRFSS. Military Medicine. 2015;180(11):1161–1169. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Prokos A, Padavic, Irene. Earn all that you can earn: income differences between women Veterans and non-Veterans. Journal of Political and Military Sociology. 2000;28.

- 112.Randall Malcom, Kilpatrick Kerry E., Pendergast Jane F., Jones Katherine R., Vogel W Bruce. Differences in Patient Characteristics Between Veterans Administration and Community Hospitals. Medical Care. 1987;25(11):1099–1104. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rosenheck Robert, Koegel Paul. Characteristics of Veterans and Nonveterans in Three Samples of Homeless Men. Psychiatric Services. 1993;44(9):858–863. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.9.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rosenheck R, Frisman L, Chung A M. The proportion of veterans among homeless men. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(3):466–469. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.3.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ryan Elizabeth T., McGrath Ashlee C., Creech Suzannah K., Borsari Brian. Predicting utilization of healthcare services in the veterans health administration by returning women veterans: The role of trauma exposure and symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Psychological Services. 2015;12(4):412–419. doi: 10.1037/ser0000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Saban KL, Bryant, F. B.,Reda, D. J.,Stroupe, K. T.,Hynes, D. M. Measurement invariance of the kidney disease and quality of life instrument (KDQOL-SF) across veterans and non-veterans. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 117.Sayer NA, Orazem, Robert J., Noorbaloochi, Siamak, Gravely, Amy, Frazier, Patricia, Carlson, Kathleen F., Schnurr, Paula P., Oleson, Heather. Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans with reintegration problems: differences by Veterans Affairs healthcare user status. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015;42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 118.Schultz Jessica R., Bell Kathryn M., Naugle Amy E., Polusny Melissa A. Child Sexual Abuse and Adulthood Sexual Assault among Military Veteran and Civilian Women. Military Medicine. 2006;171(8):723–728. doi: 10.7205/MILMED.171.8.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shen Chan, Sambamoorthi Usha. Associations Between Health-Related Quality of Life and Financial Barriers to Care Among Women Veterans and Women Non-Veterans. Women & Health. 2012;52(1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.641713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Simpson Tracy L., Balsam Kimberly F., Cochran Bryan N., Lehavot Keren, Gold Sari D. Veterans administration health care utilization among sexual minority veterans. Psychological Services. 2013;10(2):223–232. doi: 10.1037/a0031281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Smith Irving, Marsh Kris, Segal David R. The World War II Veteran Advantage? A Lifetime Cross-Sectional Study of Social Status Attainment. Armed Forces & Society. 2010;38(1):5–26. doi: 10.1177/0095327X10390463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Smith Richard W., Young Harl H. Symptom Patterns of Psychiatrically Diagnosed Veterans Who Request Treatment and Those Who Do Not. Psychological Reports. 1968;22(3):1001–1005. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1968.22.3.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sparks PJ, Bollinger, Mary. A demographic profile of obesity in the adult and Veteran US populations in 2008. Population Research and Policy Review. 2011;30.

- 124.Teachman Jay. Military Service in the Vietnam Era and Educational Attainment. Sociology of Education. 2005;78(1):50–68. doi: 10.1177/003804070507800103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Teachman Jay. Are veterans healthier? Military service and health at age 40 in the all-volunteer era. Social Science Research. 2011;40(1):326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Teachman Jay D., Call Vaughn R.A. The Effect of Military Service on Educational, Occupational, and Income Attainment. Social Science Research. 1996;25(1):1–31. doi: 10.1006/ssre.1996.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tessler R, Rosenheck, R.,Gamache, G. Comparison of homeless veterans with other homeless men in a large clinical outreach program. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2002;73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 128.Tessler Richard, Rosenheck Robert, Gamache Gail. Homeless Veterans of the Mil-Volunteer Force: A Social Selection Perspective. Armed Forces & Society. 2003;29(4):509–524. doi: 10.1177/0095327X0302900403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tran Thanh V., Canfield Julie, Chan Keith. The association between unemployment status and physical health among veterans and civilians in the United States. Social Work in Health Care. 2016;55(9):720–731. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2016.1191582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tsai Jack, Mares Alvin S., Rosenheck Robert A. Do Homeless Veterans Have the Same Needs and Outcomes as Non-Veterans? Military Medicine. 2012;177(1):27–31. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tsai J, Mota, N. P.,Pietrzak, R. H. U.S. Female Veterans who do and do not rely on VA Health Care: needs and barriers to mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 132.Vinokur Amiram, Caplan Robert D., Williams Cindy C. Effects of Recent and Past Stress on Mental Health: Coping with Unemployment Among Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1987;17(8):710–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1987.tb00335.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Vollmer TL, Hadjimichael, O.,Preiningerova, J.,Ni, W.,Buenconsejo, J. Disability and treatment patterns of multiple sclerosis patients in United States: a comparison of veterans and nonveterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development. 2002;39. [PubMed]

- 134.Washington Donna L., Yano Elizabeth M., Simon Barbara, Sun Su. To use or not to use. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(S3):S11–S18. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Washington Donna L., Gray Kristen, Hoerster Katherine D., Katon Jodie G., Cochrane Barbara B., LaMonte Michael J., Weitlauf Julie C., Groessl Erik, Bastian Lori, Vitolins Mara Z., Tinker Lesley. Trajectories in Physical Activity and Sedentary Time Among Women Veterans in the Women’s Health Initiative. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S27–S39. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Washington Donna L., Bird Chloe E., LaMonte Michael J., Goldstein Karen M., Rillamas-Sun Eileen, Stefanick Marcia L., Woods Nancy F., Bastian Lori A., Gass Margery, Weitlauf Julie C. Military Generation and Its Relationship to Mortality in Women Veterans in the Women’s Health Initiative. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S126–S137. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.West Alan, Weeks William B. Physical and Mental Health and Access to Care Among Nonmetropolitan Veterans Health Administration Patients Younger Than 65 Years. The Journal of Rural Health. 2006;22(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.West Alan N., Weeks William B. Health Care Expenditures for Urban and Rural Veterans in Veterans Health Administration Care. Health Services Research. 2009;44(5p1):1718–1734. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.White Michael D., Mulvey Philip, Fox Andrew M., Choate David. A Hero’s Welcome? Exploring the Prevalence and Problems of Military Veterans in the Arrestee Population. Justice Quarterly. 2012;29(2):258–286. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2011.560890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140.White R, Barber, Catherine, Azrael, Deb, Mukamal, Kenneth J., Miller, Matthew. History of military service and the risk of suicidal ideation: findings from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2011;41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 141.Whiteman Shawn D., Barry Adam E., Mroczek Daniel K., MacDermid Wadsworth Shelley. The development and implications of peer emotional support for student service members/veterans and civilian college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60(2):265–278. doi: 10.1037/a0031650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Widome Rachel, Laska Melissa Nelson, Gulden Ashley, Fu Steven S., Lust Katherine. Health Risk Behaviors of Afghanistan and Iraq War Veterans Attending College. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2011;26(2):101–108. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090826-QUAN-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Williams Brie A., McGuire James, Lindsay Rebecca G., Baillargeon Jacques, Cenzer Irena Stijacic, Lee Sei J., Kushel Margot. Coming Home: Health Status and Homelessness Risk of Older Pre-release Prisoners. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(10):1038–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1416-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wilmoth Janet M., London Andrew S., Heflin Colleen M. Economic Well-Being Among Older-Adult Households: Variation by Veteran and Disability Status. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2015;58(4):399–419. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2015.1019657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Winkleby MA, Fleshin, D., Physical, addictive, and psychiatric disorders among homeless veterans and nonveterans. Public Health Reports. 1993;108. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 146.Wittrock S, Ono, Sarah, Stewart, Kenda, Reisinger, Heather Schacht, Charlton, Mary. Unclaimed health care benefits: a mixed?method analysis of rural veterans. The Journal of Rural Health. 2015;31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 147.Wong Edwin S., Wang Virginia, Liu Chuan-Fen, Hebert Paul L., Maciejewski Matthew L. Do Veterans Health Administration Enrollees Generalize to Other Populations? Medical Care Research and Review. 2015;73(4):493–507. doi: 10.1177/1077558715617382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zemencuk JK, Hayward, R. A.,Skarupski, K. A.,Katz, S. J. Patients’ desires and expectations for medical care: a challenge to improving patient satisfaction. American Journal of Medical Quality. 1999;14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 149.Smith Diane L. The relationship of disability and employment for veterans from the 2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Work. 2015;51(2):349–363. doi: 10.3233/WOR-141979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bernard DM, Selden TM. Access to care among nonelderly Veterans. Med Care. 2016;54(3):243–52. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.CDC Mobidity and mortality weekly report rural health series. Accessed March 21 2018.

- 152.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Affairs DoV. Blueprint for excellence: Veterans Health Administration.

- 154.Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(10):1675–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Wang L, Elder GH, Jr, Spence NJ. Status configurations, military service and higher education. Social Forces. 2012;91(2):397–422. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 62 kb)