Abstract

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a well-characterized, abundant protein kinase that regulates a diverse set of functions in a tissue-specific manner. For example, in heart muscle, CaMKII regulates Ca2+ homeostasis, whereas in neurons, CaMKII regulates activity-dependent dendritic remodeling and long-term potentiation (LTP), a neurobiological correlate of learning and memory. Previously, we identified the GTPase Rem2 as a critical regulator of dendrite branching and homeostatic plasticity in the vertebrate nervous system. Here, we report that Rem2 directly interacts with CaMKII and potently inhibits the activity of the intact holoenzyme, a previously unknown Rem2 function. Our results suggest that Rem2 inhibition involves interaction with both the CaMKII hub domain and substrate recognition domain. Moreover, we found that Rem2-mediated inhibition of CaMKII regulates dendritic branching in cultured hippocampal neurons. Lastly, we report that substitution of two key amino acid residues in the Rem2 N terminus (Arg-79 and Arg-80) completely abolishes its ability to inhibit CaMKII. We propose that our biochemical findings will enable further studies unraveling the functional significance of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII in cells.

Keywords: calcium, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), GTPase, inhibitor, phosphorylation, autophosphorylation, Rem2, RGK family

Introduction

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) 3 is an abundant, multifunctional serine-threonine kinase whose regulation and activity are uniquely sensitive to intracellular Ca2+ levels (1–3). The functions of CaMKII are best understood in excitable cell types such as neurons where Ca2+ signaling plays a critical role in the functional output of these cells. Well-described roles for CaMKII in neurons include regulation of gene expression, synaptic plasticity (e.g. long-term potentiation), ion channel function, and modulation of the cytoskeleton (1, 4). Along these lines, ion channels such as α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, voltage-gated calcium and potassium channels, and the transcription factor cAMP-response element–binding protein (CREB) are all well-described CaMKII substrates (5–7).

Upon neuronal depolarization, activation of CaMKII is mediated by calcium-bound calmodulin and subsequent autophosphorylation, whereas turning off the kinase activity of CaMKII is regulated in part by cytosolic phosphatases (8). However, during certain cellular processes such as synaptic potentiation, CaMKII accumulates in cellular regions with a low local concentration of phosphatases (9, 10). How uncontrolled kinase activity is avoided in those circumstances remains an open question. One potential mechanism would be the activity-regulated expression of endogenous CaMKII inhibitors. Thus far, only a few endogenous inhibitors of CaMKII have been described in mammals, and regulation of their expression is not well-understood (11, 12).

We previously showed that Rem2 is an activity-regulated gene as its mRNA expression is up-regulated by neuronal depolarization both in vitro and in vivo (13, 14), and the Rem2 protein is also subject to activity-dependent post-translational modification (15). Moreover, we demonstrated using gene knockdown approaches in cultured rodent neurons and Xenopus laevis optic tectum that Rem2 regulates dendritic branching (13, 16) in conjunction with CaMKII signaling. In addition, overexpression of Rem2 in various cell types profoundly inhibits high voltage–activated Ca2+ channels (17–20); CaMKII also modulates the properties of voltage-gated calcium channels (21–24).

Rem2 is expressed in several tissues but predominantly in the brain where all four CaMKII isozymes are also present (25). Rem2 is a member of the RGK subfamily (Rem2, Rad, Rem, and Gem/Kir) of the Ras superfamily of monomeric G-proteins (26). A number of features differentiate RGK family members from the Ras superfamily. For example, the crystal structures of the GTPase domain of several RGK proteins, including Rem2, reveal differences between this family and classical GTPases in the structure of their nucleotide-binding domains (27, 28). In addition, RGK proteins contain extended N and C termini relative to other Ras family members (19). Thus, for these and other reasons (18, 19), Rem2 and the RGK family members in general may not behave as classical Ras-like GTPases regulated by their nucleotide-binding state.

As an inroad to obtaining a more detailed understanding of Rem2 signaling, we took an unbiased approach to identify Rem2-interacting proteins. Here, we present data demonstrating that Rem2 interacts with CaMKII and is a novel inhibitor of CaMKII activity. Our biochemical analysis of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII allowed us to generate point mutations that abolish Rem2-mediated inhibition of CaMKII and that will be a valuable reagent in future studies probing Rem2–CaMKII function. Taken together, our findings have important implications for regulation of synaptic plasticity and activity-dependent neuronal remodeling in the mammalian brain.

Results

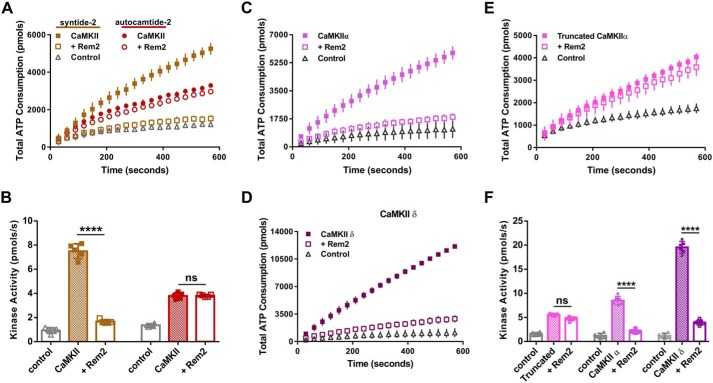

To identify molecules that potentially interact with Rem2 in cells, we performed a biochemical enrichment of Rem2-interacting proteins followed by MS identification. We passed whole-brain lysate from P14 rats over a column containing a maltose-binding protein (MBP)-Rem2 fusion protein bound to amylose-agarose or an MBP-alone control column. Bound proteins were eluted and separated by SDS-PAGE, and protein bands specifically bound to MBP-Rem2 were visually identified (Fig. S1A) and further analyzed by MS. Using this approach, all four isozymes of CaMKII were identified (Fig. 1A). However, given the mixed holoenzyme nature of CaMKII, it is possible that Rem2 directly interacts with only one or a subset of the isozymes. In addition to CaMKII, other previously identified Rem2-interacting proteins such as 14-3-3 and calmodulin were also detected (29, 30).

Figure 1.

Rem2 binds to CaMKII. A, mass spectrometry data identifying CaMKII isozymes retained by a Rem2 affinity matrix after loading with total brain lysate from P14 WT rats. The number of unique and total peptides and the percentage of the protein sequence covered for each isozyme are shown. B, coimmunoprecipitation of Rem2 and CaMKIIα from HEK293T cells transfected with HA-tagged Rem2, myc-tagged CaMKIIα, or both. Rem2 was immunoprecipitated using an anti-HA antibody. Anti-myc and anti-HA immunoblotting was performed to detect CaMKIIα and Rem2, respectively. C, coimmunoprecipitation of Rem2 and CaMKIIα from mouse brain lysates using goat anti-Rem2 antibody. Immunoblotting was performed using rabbit anti-Rem2 and mouse anti-CaMKIIα antibodies to detect Rem2 and CaMKIIα, respectively. The numbers represent the position of protein molecular mass standards in kDa. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblotting. The experiment was repeated three times.

Although Rem2 is a substrate of CaMKII in vitro (15), our ability to detect the CaMKII–Rem2 interaction by affinity chromatography suggests a more stable interaction between Rem2 and CaMKII than that which is typical between a kinase and substrate. To confirm the in vivo association of Rem2 with CaMKII, we performed two different coimmunoprecipitation assays. First, we demonstrated that an HA epitope–tagged Rem2 protein (HA-Rem2) and a myc epitope–tagged CaMKIIα protein expressed in HEK293T cells coimmunoprecipitate using an anti-HA antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-myc antibody (Fig. 1B). These data are consistent with previous reports showing that Rem2 interacts with CaMKIIα in 293T cells (31).

Next, we asked whether the endogenous Rem2 and CaMKII proteins associate in lysates obtained from mouse hippocampus. Rem2 was immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal goat antibody; normal goat serum was used as a negative control (Fig. 1C). Immunoblotting with a rabbit polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes Rem2 (16) revealed the presence of Rem2 in both the lysate and the goat Rem2 immunoprecipitated samples but not in the goat serum control samples (Fig. 1C, left panel). Importantly, immunoblotting with monoclonal CaMKIIα antibody demonstrated that CaMKII associates with Rem2 in mouse hippocampal lysates (Fig. 1C, right panel).

To examine the relationship between Rem2 and CaMKII, we took an in vitro approach to ask what effect Rem2 has on CaMKII activity. We purified recombinant Rem2 and CaMKIIα holoenzyme, the main isozyme expressed in the adult brain (32), from Escherichia coli. Gel filtration analysis and negative stained EM images of the peak fraction of the purified CaMKIIα are consistent with a dodecameric form of the holoenzyme in this preparation (Fig. S1, B–D). To test the kinase activity of the enzyme, we used the classic pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase (PK/LDH) coupled assay (33, 34). In this assay, the production of ADP by the phosphorylation reaction of the kinase is coupled to the decay of NADH to NAD+ in a 1:1 molar ratio. Thus, monitoring the rate of NADH decay by spectrophotometry provides a quantification of ADP production and thus ATPase activity. Using this assay, we determined that our preparation of CaMKIIα is active using syntide-2 as a substrate (Fig. 2, A and B).

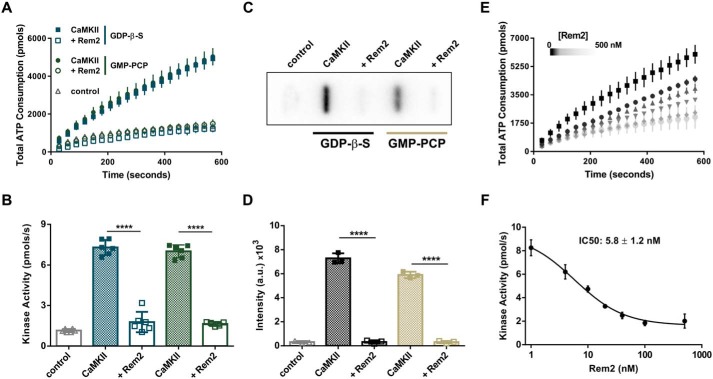

Figure 2.

Rem2 is an inhibitor of CaMKIIα. A, ATP consumption by purified CaMKIIα (20 nm monomer) monitored using the PK/LDH assay with syntide-2 as a substrate (200 μm) with (open symbols) or without 500 nm Rem2 (filled symbols) in the presence of 40 μm GDP-β-S (blue squares) or 40 μm GMP-PCP (green circles). Samples devoid of CaMKIIα were used as negative controls (gray triangles). B, quantification (see “Experimental procedures”) of CaMKIIα kinase activity shown in A (n = 6; error bars indicate standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). In this panel and all subsequent figures, individual points in the scatter plot represent one experiment. C, representative image of a slot-blot of 32P-labeled syntide-2 exposed to a phosphorimaging plate. The phosphorylation of syntide-2 (200 μm) by CaMKIIα (20 nm) was conducted in the presence of radiolabeled ATP for 8 min in the presence (500 nm) or absence of Rem2 and either 40 μm GDP-β-S or 40 μm GMP-PCP as indicated. Samples without syntide-2 were used as controls. D, quantification of all syntide-2 experiments as in C (n = 3; standard deviations are shown; ****, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). E, concentration dependence of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKIIα kinase activity toward syntide-2. Black squares, 0 nm Rem2; black circles, 4 nm Rem2; upward triangles, 10 nm Rem2; downward triangles, 20 nm Rem2; gray diamonds, 40 nm Rem2; light gray circles, 100 nm Rem2. F, dose-response plot of the data shown in E. The average value of the slope of each curve was plotted as a function of Rem2 concentration (anti-log scale). The IC50 is 5.8 ± 1.2 nm and was obtained from the nonlinear fit of the points (see “Experimental procedures”).

Interestingly, CaMKIIα kinase activity is strongly inhibited by addition of Rem2 to the assay (Fig. 2, A–F). In fact, Rem2 completely inhibits CaMKIIα activity, limiting ADP production to a level equal to our control condition that lacks CaMKIIα. As Rem2 is a GTPase, we asked whether the identity of nucleotide bound to Rem2 affects its ability to inhibit CaMKII kinase activity. We found no difference in the ability of Rem2 to inhibit CaMKII activity using nonhydrolyzable analogs of GTP (GMP-PCP) or GDP (GDP-β-S) in our assay (Fig. 2, A and B). It is important to note that, under our experimental conditions, the concentration of guanine nucleotides used (40 μm) is saturating for Rem2, whereas CaMKIIα kinase activity has been shown to be unaffected by this concentration of guanine nucleotides (26, 35). Accordingly, addition of the nucleotides in the absence of Rem2 did not alter the kinase activity of CaMKII (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, CaMKIIα inhibition by Rem2 was also observed in the absence of guanine nucleotides (see Fig. 6, C–F, below). These results suggest that the mechanism of inhibition is independent of which nucleotide is bound to Rem2.

Figure 6.

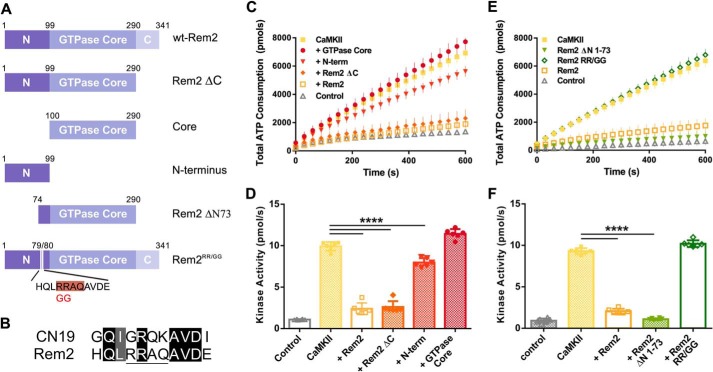

Effect of Rem2 mutants on CaMKIIα kinase activity. A, diagram of deletion and point mutants of Rem2 used in this study. The amino acid residue numbering refers to the mouse protein sequence. N, N-terminal domain (residues 1–99); C, C-terminal domain (residues 291–341). The Rem2-ΔN73 mutant lacks the first 73 amino acids. Rem2RR/GG corresponds to the full-length protein containing the R79G and R80G mutations. The pink highlighting indicates the pseudosubstrate site in the amino acid sequence below the cartoon. B, the amino acid sequence of the CaMKII inhibitory peptide CN19 is aligned with residues 76–86 from the Rem2 N terminus. Sequence identity and similarity are marked by the black and gray highlights, respectively. The pseudosubstrate sequence present in the Rem2 N terminus is underlined. C, ATP consumption by purified CaMKIIα using syntide-2 as substrate in the presence of Rem2 or one of its mutants (at 500 nm each). Filled squares, CaMKII; circles, GTPase core; diamonds, Rem2-ΔC mutant; downward triangles, Rem2 N terminus (N-term); orange open squares, full-length Rem2; upward triangles, negative control. D, quantification of the CaMKIIα kinase activity described in C using the same color code (n = 6; error bars depict standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). E, ATP consumption by purified CaMKIIα using syntide-2 as substrate in the presence of Rem2RR/GG (open diamonds), Rem2-ΔN1–73 (downward triangles), or full-length Rem2 (orange open squares). All proteins were present at 500 nm. Filled squares and upward triangles represent positive and negative controls, respectively. F, quantification of the CaMKIIα kinase activity described in E using the same color code (n = 6; error bars depict standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test).

We sought to confirm these results using a direct kinase assay method, monitoring the incorporation of radiolabeled phosphate from [γ-32P]ATP into the peptide substrate syntide-2 under the same experimental conditions. In agreement with our observations using the PK/LDH assay, we found that phosphorylation of syntide-2 by CaMKIIα is significantly decreased in the presence of Rem2 and either GMP-PCP or GDP-β-S (Fig. 2, C and D). Importantly, inhibition of CaMKIIα by Rem2 was also observed when a full-length protein, glycogen synthase, was used as substrate (Fig. S2).

Next, we determined the IC50 by titration of Rem2 protein in our PK/LDH assay. We found that Rem2 is a potent inhibitor of CaMKII with an apparent IC50 of ∼6 nm using the peptide syntide-2 as substrate (Fig. 2, E and F). For comparison, the IC50 of the inhibitory domain of densin and of the CaMKII inhibitor CaMKIIN on the same substrate is 49 and 50 nm, respectively (12, 36).

We then proceeded to investigate the properties of this inhibition. First, we sought to determine whether Rem2 interferes with the activation of CaMKII by Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM). We titrated the amount of CaM present in the PK/LDH assay in the presence or absence of 500 nm Rem2 (Fig. 3, A and B). We found that Rem2 efficiently inhibited CaMKII activity over a wide range of CaM concentrations equal to or above the Rem2 concentration in the assay (i.e. 40-fold; 0.5–20 μm), indicating that Rem2 is unlikely to act simply as a CaM scavenger.

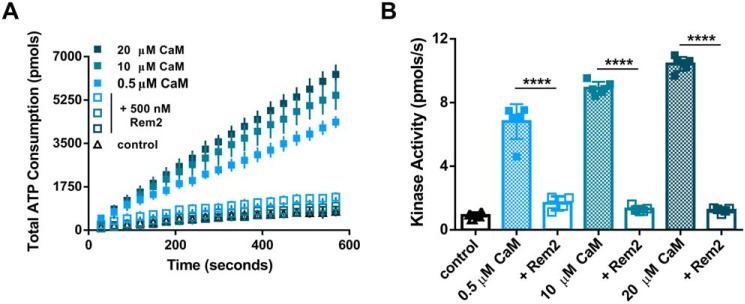

Figure 3.

Rem2 inhibits CaMKIIα over a wide range of calmodulin concentrations. A, total ATP consumption during the phosphorylation of syntide-2 by CaMKIIα was monitored at different concentrations of CaM (filled squares; 40-fold range). Addition of 500 nm Rem2 (open squares) reduced the ATP consumption to control levels (triangles) at any CaM concentration tested. B, quantification of the CaMKIIα kinase activity shown in A using the same color code (n = 6 for all CaM only conditions; n = 4 for 0.5 μm + Rem2 condition; n = 5 for all other conditions; error bars depict standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test).

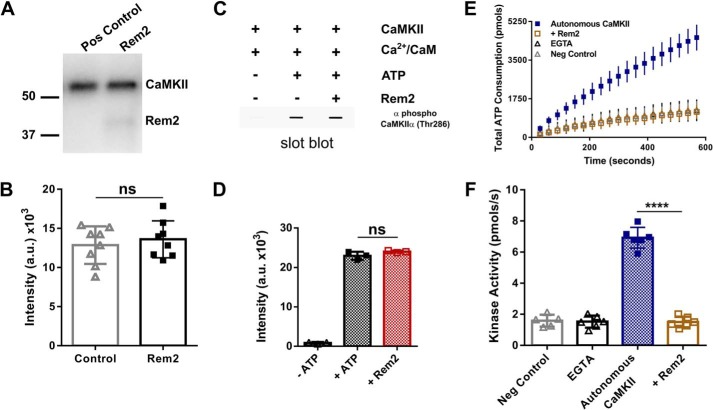

Next, we asked whether Rem2 inhibited CaMKII autophosphorylation. In this experiment, autophosphorylation of CaMKIIα was induced by incubation of the enzyme with Ca2+/CaM and [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of 500 nm Rem2 for 2 min (Fig. 4). This incubation time has been shown to produce strong phosphorylation at the CaMKII autophosphorylation site residue Thr-286 (37). The reaction mixture was separated by SDS-PAGE, and the radioactivity of 32P-labeled CaMKIIα was measured using a phosphorimaging system (Fig. 4, A and B). We found no difference in CaMKII autophosphorylation in the presence or absence of Rem2. This result indicates that Rem2 does not inhibit CaMKII autophosphorylation, suggesting that it is unlikely that Rem2 acts by hindering CaM binding to the regulatory domain of CaMKII. We confirmed this result by monitoring phosphorylation at the Thr-286 residue of CaMKIIα using slot-blotting and a Thr-286 phosphospecific antibody (Fig. 4, C and D). Strong immunoreactivity was observed when CaMKIIα was incubated with Ca2+/CaM in the presence of ATP as expected. Addition of Rem2 to the reaction did not alter the extent of CaMKIIα autophosphorylation on Thr-286. Taken together, these experiments suggest that Rem2 acts as an inhibitor of CaMKII catalytic activity on substrates other than the CaMKII regulatory domain.

Figure 4.

Rem2 inhibits autonomous CaMKIIα but not CaMKII autophosphorylation at Thr-286. A, autophosphorylation of CaMKIIα (80 nm) was induced by incubation of the enzyme with Ca2+/CaM (1 mm/3.33 μm) and [γ-32P]ATP (100 μm) in the absence or presence of 500 nm Rem2 for 2 min. The reaction mixture was separated by SDS-PAGE, the gel was dried, and visualization and quantification of 32P-labeled proteins were obtained using a phosphorimaging system. A representative experiment is shown. The numbers represent the position of protein molecular mass standards in kDa. B, quantification of all CaMKIIα autophosphorylation experiments as in A (n = 8; standard deviations are shown; ns, not significantly different (p = 0.7768), Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test). C, representative experiment of slot-blot analysis of CaMKIIα using an antibody specific for phospho-Thr-286. CaMKIIα was incubated for 2 min with the reagents indicated above the blot. D, quantification of all experiments as in C (n = 9; standard deviations are shown; ns, not significantly different, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). E, CaMKIIα (60 nm) was preincubated with ATP (500 μm) and Ca2+/CaM (1 mm/10 μm) for 2 min at room temperature to promote CaMKIIα autophosphorylation and autonomous activity. The preincubated mixture was then exposed to syntide-2 (200 μm) ([Ca2+] < 50 nm). The total ATP consumption as a function of time in the absence (blue squares) or presence of Rem2 (500 nm; gold squares) is shown. Addition of EGTA during the preincubation was used to confirm that only the autonomous activity was assayed (black triangles). A negative control (gray diamonds) was conducted in the absence of CaMKIIα. F, the kinase activity of CaMKIIα in each of the conditions described in E is shown using the same color code (n = 6; error bars depict standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). Pos, positive; Neg, negative; a.u., arbitrary units.

Next, we sought to determine whether Rem2 interferes with the catalytic activity of the Ca2+/CaM-independent, autonomous form of the enzyme on syntide-2. CaMKIIα was preincubated with ATP and Ca2+/CaM for 2 min to promote CaMKIIα autophosphorylation at residue Thr-286 and CaMKIIα autonomous activity (37). After the incubation, free calcium in the solution was brought to values below 50 nm by addition of EGTA to suppress any Ca2+/CaM-dependent activity. The preincubated mixture was then immediately used in the PK/LDH assay in the presence or absence of 500 nm Rem2 using syntide-2 as a substrate (Fig. 4, E and F). As a negative control, we added EGTA during the CaMKII preincubation to confirm that only the CaMKII autonomous activity was assayed (Fig. 4, E and F). We found that addition of Rem2 after CaMKII preincubation caused a substantial decrease in total ATP consumption, indicating a strong inhibition of the autonomous activity of CaMKIIα.

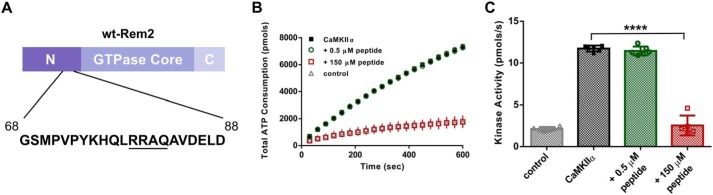

Because we observed that Rem2 inhibits the catalytic activity of CaMKII, we next asked whether Rem2 selectively inhibits CaMKII phosphorylation of specific types of substrates that are known to bind to different regions of the catalytic domain (i.e. S- and T-sites (38)). Using the PK/LDH assay, we compared the efficacy of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII using the peptides syntide-2 and autocamtide-2 as models of S- and T-type substrates, respectively (Fig. 5, A and B). We found that Rem2 is a much more potent inhibitor of CaMKII activity on syntide-2, indicating a preference for Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII activity on S-type substrates, thus hinting at a substrate-specific mechanism of Rem2 inhibition. A similar selectivity has been described for the CN21a inhibitory peptide and the densin internal domain (36, 38).

Figure 5.

Specificity of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII. A, ATP consumption by purified CaMKIIα monitored using the PK/LDH assay with syntide-2 (S-type substrate; 200 μm; gold filled squares) and autocamtide-2 (T-type substrate; 200 μm; red filled circles). Addition of 500 nm Rem2 produced a strong inhibition of syntide-2 phosphorylation (gold open squares) but not of autocamtide-2 (red open circles). The control is the reaction minus CaMKIIα (gray triangles). For clarity, only the syntide-2 control is shown. B, quantification of the CaMKIIα kinase activity described in A using the same color code (n = 5; error bars depict standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001; ns, not significantly different, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test). C and D, ATP consumption by 20 nm purified CaMKIIα (C, filled squares) and CaMKIIδ isoforms (D, filled squares) with syntide-2 (200 μm) in the absence or presence of Rem2 (500 nm; open squares). Negative controls (gray triangles) did not contain the respective CaMKII isoform. E, ATP consumption by monomer of rat CaMKIIα that lacks the association domain (residues 1–325) (20 nm monomer) monitored using the PK/LDH assay with syntide-2 (200 μm) in the absence (filled squares) or presence of 500 nm Rem2 (open squares). F, quantification of the kinase activity of CaMKII shown in C, D, and E using the same color code (n = 6 for all groups; error bars depict standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001; ns, not significantly different, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test).

We sought to gain further insight into the functional implications of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII by investigating whether the inhibition is CaMKII isozyme–specific. Interestingly, peptides from all four CaMKII isozymes were identified in our MS analysis, suggesting that Rem2 does not interact exclusively with the α isoform. Thus, we chose to extend our inhibition studies to the CaMKIIδ isozyme, which is expressed in neuronal and nonneuronal cells but is also the major cardiac CaMKII (25) (Fig. 5, C, D, and F). We found that Rem2 is a potent inhibitor of CaMKIIδ, similar to its effect on CaMKIIα, demonstrating that Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII is not restricted to the α isoform.

The conservation of Rem2 function with respect to CaMKII isozymes argues that the regions required for Rem2 inhibition are likely contained within conserved segments of the CaMKII protein. To test this idea, we used a commercially available monomeric version of CaMKIIα (New England Biolabs). This monomeric version of the kinase is truncated at position 325 and thus lacks the association domain but retains the catalytic and the regulatory Ca2+/CaM-binding domains. We found that Rem2 displays only a weak inhibitory effect on syntide-2 phosphorylation using this truncated version of CaMKIIα (Fig. 5, E and F). This result suggests that potent Rem2 inhibition requires the association domain and is specific for the holoenzyme, the physiologically relevant form of the enzyme. Interestingly, our result is similar to the preferential binding of the densin C terminus to the holoenzyme form of CaMKIIα (36).

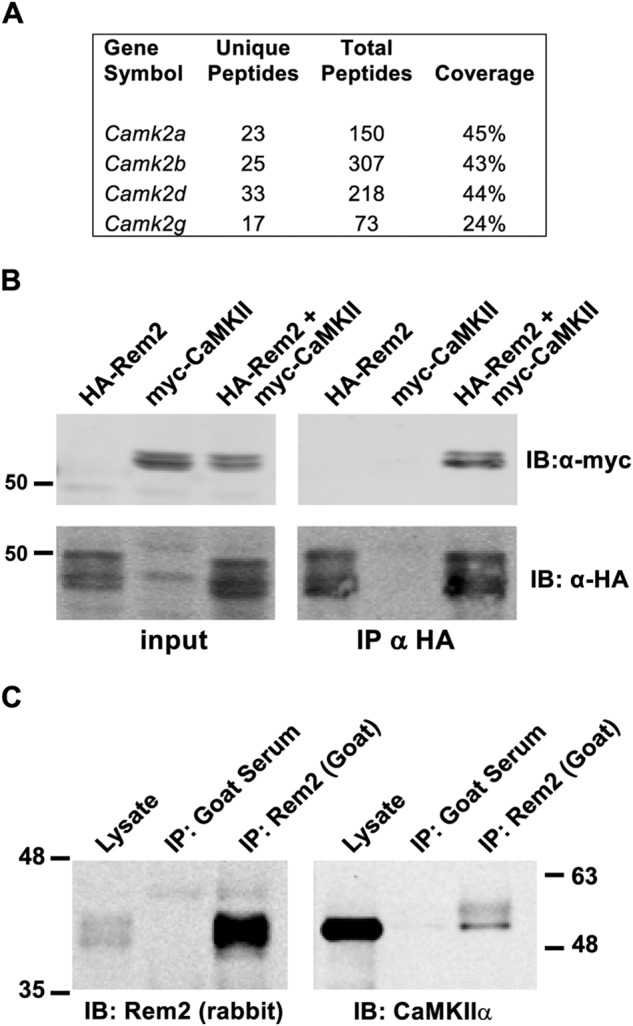

To gain insight into the cellular relevance of Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII, we began mapping the protein domains involved in the interaction. We purified deletion mutants of Rem2 and compared the ability of these Rem2 mutants to inhibit CaMKII with the full-length protein. We divided Rem2 primary sequence in three major domains (N terminus, GTPase core, and C terminus) and produced deletion mutants lacking one or two of those domains (Fig. 6A).

First, we tested a Rem2 deletion lacking the C terminus, Rem2-ΔC, and found that this mutant fully inhibited the kinase activity of CaMKIIα, suggesting that this domain is not required for the inhibitory properties of Rem2 (Fig. 6, C and D). We next deleted both the N- and C-terminal domains, producing a Rem2 protein containing only the GTPase core. Interestingly, this protein could not inhibit CaMKIIα, indicating that at least part of the N-terminal domain is required for inhibition (Fig. 6, C and D). Finally, we purified the N terminus of Rem2 alone and found that, at the same concentration used for the full-length protein, the N terminus of Rem2 could only partially (19%) inhibit the kinase activity of CaMKIIα (Fig. 6, C and D). This result indicates that the GTPase core is also required and suggests that multiple domains of Rem2 are involved in CaMKII inhibition. A similar multidomain interaction with CaMKII has been described for the scaffolding protein densin (36, 39).

The fact that the Rem2 N terminus alone retains some inhibitory capacity, taken together with our data suggesting that Rem2 inhibits CaMKII substrate recognition at the S-site, prompted us to search the N-terminal primary amino acid sequence for pseudo-CaMKII substrate sequences. We identified a pseudosubstrate sequence (Fig. 6B) in the distal portion of the domain and designed a deletion mutant lacking the sequence upstream to this sequence, Rem2-ΔN73. As shown in Fig. 6, E and F, the Rem2-ΔN73 protein completely inhibits CaMKIIα activity, indicating that at least one of the required inhibitory sequences is contained within Rem2 amino acids 74–99.

We further refined our analysis by disrupting the pseudosubstrate recognition sequence by inserting two point mutations, R79G and R80G, into full-length Rem2; we call this protein Rem2RR/GG. Accordingly, the purified Rem2RR/GG mutant protein failed to inhibit the kinase activity of CaMKIIα (Fig. 6, E and F), indicating that the pseudosubstrate sequence is required for inhibition. Importantly, this mutant version of Rem2 retains the ability to inhibit calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (17–20) in a cultured cell assay, indicating that the RR/GG mutation does not completely disrupt Rem2 function (Fig. S3).

The purified N terminus is only a weak inhibitor of CaMKII (Fig. 6, C and D), suggesting the existence of a multidomain interaction between Rem2 and CaMKII that may serve to increase the effective concentration of the N terminus of Rem2 at the S-site. In this case, a high concentration of a peptide identical to the region of Rem2 N terminus containing the pseudosubstrate sequence should be able to inhibit CaMKII. To test this hypothesis, we obtained a 21-amino-acid peptide corresponding to residues 68–88 of Rem2 N-terminal domain (Fig. 7A). Next, we tested the ability of the peptide to inhibit CaMKIIα kinase activity at two concentrations, 0.5 and 150 μm (Fig. 7B). We found that CaMKIIα was strongly inhibited when the peptide was added at 150 μm (Fig. 7C) but not 0.5 μm in agreement with the above hypothesis. It is interesting to note that the N-terminal 99 amino acids alone weakly inhibit CaMKII at 500 nm (Fig. 6), whereas the 21-mer peptide does not inhibit at this concentration (Fig. 7). One possible explanation for this result is that other residues within the N-terminal 99 amino acids are able to interact with CaMKII and therefore increase the local concentration of the pseudosubstrate or perhaps present the pseudosubstrate sequence in a particular conformation, increasing binding efficiency to the S-site.

Figure 7.

A peptide based on amino acids 68–88 from the N terminus of Rem2 is a low-affinity CaMKII inhibitor. A, scheme depicting a 21-amino-acid peptide corresponding to the mouse Rem2 sequence between amino acid residues 68 and 88. The CaMKII pseudosubstrate sequence is underlined. B, total ATP consumption by purified CaMKIIα using syntide-2 as substrate (200 μm) (black squares) and in the presence of a 0.5 or 150 μm concentration of the peptide described in A (green circles and red squares, respectively). Samples devoid of syntide-2 were used as negative controls (gray triangles). C, quantification of CaMKIIα kinase activity shown in B (n = 6; error bars indicate standard deviations; ****, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's test).

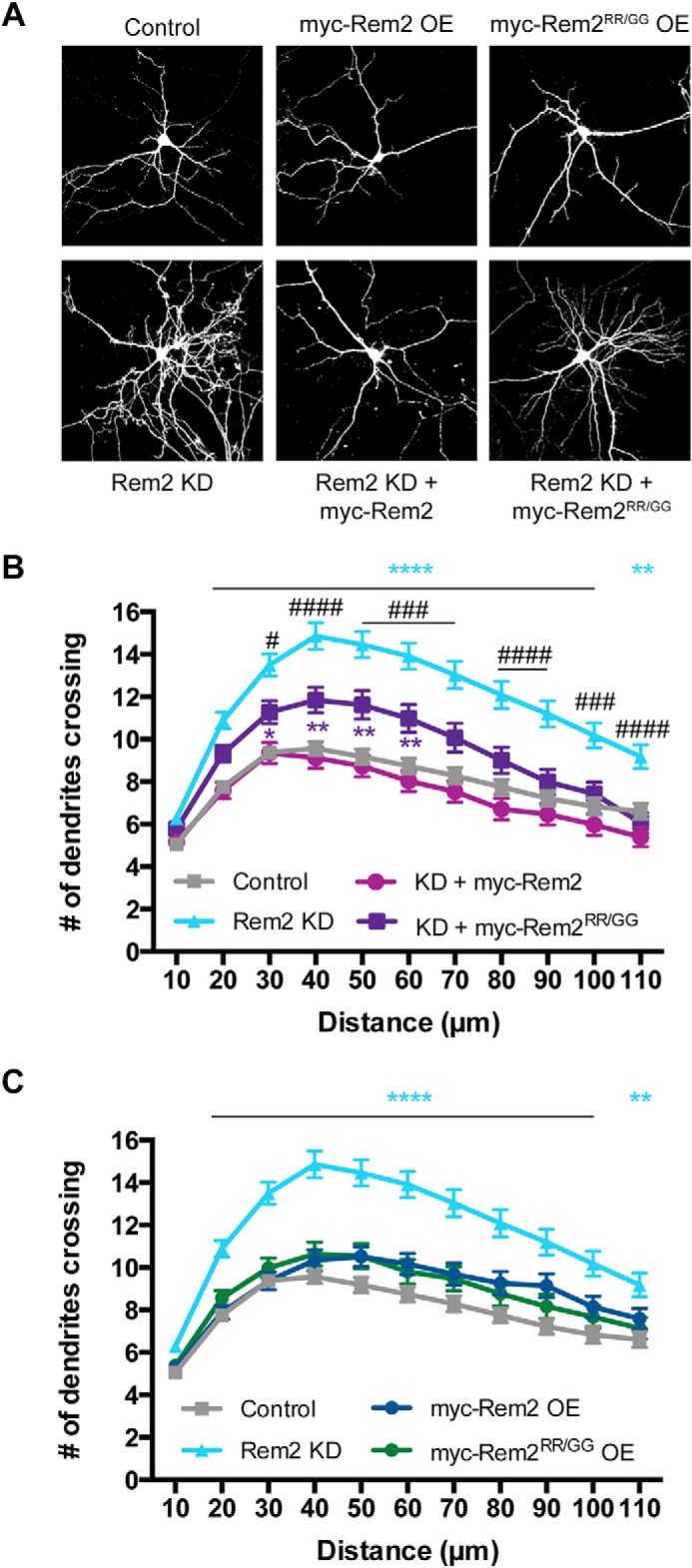

Because both Rem2 and CaMKII signaling regulates dendritic branching (40, 41), we reasoned that Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII might play a role in this process. We took advantage of the Rem2RR/GG protein to test this hypothesis in primary cultures of rat hippocampal neurons. As previously shown, knockdown of Rem2 using an RNAi reagent targeting Rem2 (Rem2 KD) led to a marked increase in dendritic branching (Fig. 8) (42). The shRNA construct used was extensively validated in previous work (see Paradis et al. (43), Fig. S2G; Ghiretti et al. (16), Fig. 1; and Moore et al. (42), Fig. 1), and the extent of knockdown is on the order of 70% in neurons under similar experimental conditions. This phenotype could be rescued by cotransfection of a plasmid encoding a Rem2 cDNA that was rendered RNAi-resistant by introduction of silent mutations into the cDNA sequence (KD + myc-Rem2 OE; Fig. 8, A and B) as was also shown previously (16). Importantly, overexpression of Rem2 alone did not affect dendritic branching (Fig. 8, A and C).

Figure 8.

Rem2 regulates dendritic complexity in part by inhibiting CaMKII catalytic activity. A, representative images of the morphology of hippocampal neurons transfected with a plasmid encoding enhanced GFP and either (upper panel, left to right) an empty vector control, myc-tagged mouse Rem2, or myc-tagged Rem2RR/GG. A similar set of experiments was done in neurons transfected with shRNA targeting Rem2 (Rem2 KD) (lower panel). The Rem2 OE constructs used are RNAi-resistant. B, quantification of dendritic branching via Sholl analysis for each condition shown in the lower panel of A (control, n = 91; Rem2 KD, 86; Rem2 KD + WT Rem2 rescue, 66; Rem2 KD + Rem2RR/GG, 84); error bars depict standard error. C, quantification of dendritic branching via Sholl analysis for each condition shown in the upper panel of A. Control and Rem2 KD traces from B are replotted for comparison (control, n = 91; Rem2 KD, 86; Rem2 OE, 75; Rem2RR/GG OE, 71); error bars depict standard error. Blue asterisks, control versus Rem2 KD; purple asterisks, control versus Rem2 KD + myc-Rem2RR/GG; #, Rem2 KD versus Rem2 KD + myc-Rem2RR/GG. */#, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ###, p < 0.001; ****/####, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

We repeated the rescue experiment described above using a RNAi-resistant version of the Rem2RR/GG mutant (myc-Rem2RR/GG). First, we determined that myc-Rem2RR/GG is expressed in cultured hippocampal neurons at levels similar to WT Rem2 (Fig. S4). Next, we determined that overexpression of the Rem2RR/GG mutant alone did not affect dendritic branching (Fig. 8, A and C), similar to results observed with WT Rem2. However, the Rem2RR/GG mutant was incapable of fully rescuing the increased branching phenotype observed upon Rem2 knockdown in contrast to WT Rem2. One interpretation of these results is that Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII modulates CaMKII-dependent dendritic branching. Furthermore, these findings imply that other CaMKII-dependent pathways exist in the cell that also regulate dendritic branching.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that Rem2 is a potent inhibitor of CaMKII catalytic activity. Interestingly, Rem2 expression and function are regulated by Ca2+ entry into cells, and modulation of CaMKII by Ca2+ is one of its most interesting features. Ca2+/calmodulin binds to the regulatory region of CaMKII, leading to exposure of the catalytic domain and activation of the enzyme (44). Subsequent phosphorylation at Thr-286 on the regulatory domain by an adjacent CaMKII monomer in the holoenzyme leads to an autonomous, Ca2+-independent kinase activity. Importantly, autonomous CaMKII is temporally uncoupled from the original cellular signal that led to its activation, potentially allowing the enzyme to act as a molecular memory of previous Ca2+ signaling events (4, 45). In addition, the unique properties of CaMKII activation allow the enzyme to integrate both the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ signaling and translate this information into specific cellular outcomes (33, 46, 47).

CaMKII inhibition could occur via a number of possible mechanisms, which would have different functional consequences for CaMKII signaling. For example, an inhibitor could act on the activation step, impede the autophosphorylation of CaMKII, or block the catalytic activity. In the first case, inhibition of enzyme activation would result in silencing all signaling events mediated by CaMKII. Alternatively, interfering with the autophosphorylation of CaMKII would allow the enzyme to be active only when Ca2+/CaM is bound, effectively converting CaMKII into a signaling component without autonomous activity, thus preventing the creation of molecular memory. Finally, an inhibitor of the catalytic activity against exogenous substrates would allow the autophosphorylation of CaMKII but prevent phosphorylation of other targets. This type of inhibition could be relevant during repetitive stimulation, permitting the formation of molecular memory but avoiding excessive phosphorylation of protein targets.

Our data indicate that Rem2 does not block CaMKII activation. Two lines of evidence support this conclusion. First, we observed that Rem2 efficiently inhibits CaMKII over a wide range of CaM concentrations (Fig. 3). Second, we found no difference in CaMKII autophosphorylation in the presence of Rem2 (Fig. 4). These results suggest that it is very unlikely that Rem2 acts by hindering CaM binding to the regulatory domain of CaMKII. Interestingly, two different groups, using immunoprecipitation from cellular lysates as their assay, reported that Rem2 interacts with CaM via an interaction with the Rem2 C-terminal domain (30, 31). Given our current findings, it is possible that this interaction is not mediated by CaM per se but instead by an interaction between Rem2 and CaM-bound CaMKII subunits. Nevertheless, our observation that the Rem2 C terminus deletion mutant retained full inhibitory properties toward CaMKII (Fig. 6) suggests that any Rem2–CaM binding mediated by the Rem2 C terminus is not relevant to its ability to inhibit CaMKII.

We propose that Rem2 inhibits the catalytic activity of CaMKII toward substrates. Analysis of Rem2 deletion mutants showed that the inhibition of CaMKII requires two distinct domains, the N terminus and the GTPase core (Fig. 6). The purified N terminus could only partially inhibit the enzyme (Fig. 6), and a peptide based on this motif only inhibited CaMKII at 150 μm (Fig. 7), suggesting that the inhibitory peptide present in this domain has a relatively weak affinity for the catalytic site of CaMKII. In turn, the GTPase core domain alone does not affect the catalytic activity of CaMKII but is required for full inhibition, suggesting that it may be required for CaMKII binding.

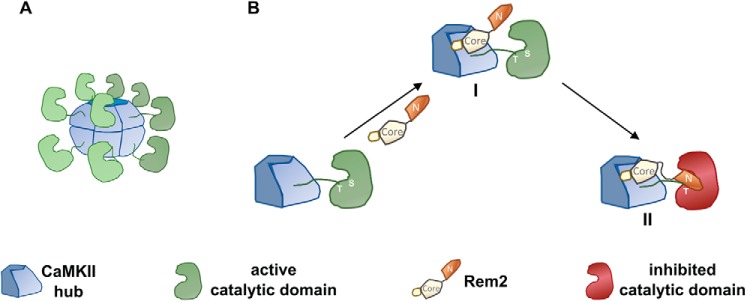

Taken together, these data led us to the following model of Rem2–CaMKII interaction and inhibition (Fig. 9). In our model, the GTPase core of Rem2 binds to the association domain of the CaMKII holoenzyme, thus increasing the local concentration of the Rem2 N terminus in proximity to the S-site where it then binds. In agreement with this model, Rem2 could not inhibit a monomeric version of CaMKII that contains the regulatory but not the association domain (Fig. 5E).

Figure 9.

Proposed model of CaMKII inhibition by Rem2. A, cartoon depicting the activated CaMKII holoenzyme. Calmodulin and some of the CaMKII monomers are not shown for clarity. B, amplified view of a CaMKII monomer shown in A. In the proposed model, the GTPase core of Rem2 binds to the association domain of CaMKII with high affinity (I). This leads to an increased local concentration of the N terminus of Rem2 and its binding to the catalytic site of CaMKII, resulting in the inhibition of the enzyme (II).

Previously our laboratory discovered that Rem2 is an activity-dependent, negative regulator of dendritic branching and functions in a CaMK signaling pathway to mediate this effect (13, 15, 16). Similarly, a number of other studies also implicated CaMKII signaling in regulation of dendritic branching (40, 48, 49), although differing effects of CaMKIIα and CaMKIIβ activity on dendritic branching have been reported (40). Whether these disparate results are due to different functions of CaMKII in various neuronal subtypes (e.g. cortical neurons, cerebellar granule neurons, etc.) or different approaches to modulation of CaMKII activity (e.g. pharmacological, constitutive mutants, etc.) or reflect a complexity of function of the endogenous holoenzyme, which may be a multimer of different CaMKII isozymes, remains to be determined.

Nonetheless, the current study further refines our understanding of Rem2 regulation of dendritic branching. Our findings suggest that Rem2 inhibition of CaMKII is at least partially responsible for shaping the dendritic arbor because a mutant version of Rem2 that is unable to inhibit CaMKII only partially rescues the increased dendritic branching observed with Rem2 knockdown. These data also imply the existence of other signaling pathways that are independent of CaMKII catalytic activity, such as Rem2-dependent changes in gene expression (50), but that also regulate dendritic branching.

One alternative interpretation of the partial rescue of the dendritic branching phenotype is that the myc-Rem2RR/GG protein is less well-expressed in neurons compared with WT myc-Rem2. However, our quantification of anti-myc-Rem2 immunostaining in cultured neurons (Fig. S4) strongly suggests that this is not the case. We also demonstrated that Rem2RR/GG retains at least some of the biological function of WT Rem2 as overexpression of the RR/GG mutant inhibited voltage-gated calcium channel function similarly to overexpression of WT Rem2 (Fig. S3).

In summary, we have demonstrated that Rem2 is a potent inhibitor of the CaMKII catalytic activity against exogenous substrates, thus allowing the autophosphorylation of CaMKII while preventing the phosphorylation of other targets. Because its own expression is activity-dependent, our results position Rem2 as a leading candidate for the regulation of CaMKII signaling during periods of high neuronal activity.

Experimental procedures

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Brandeis University.

Molecular biology

Plasmids containing full-length human CaMKIIα and -δ cDNAs were obtained from Addgene (plasmids 23408 and 23814). The cDNAs were subcloned into the pET28-lam-PPase vector. To create pET28-lam-PPase, the λ-phosphatase gene, including the ribosome-binding site, was subcloned from the vector pPET-PKR/PPase (Addgene 42934) downstream of the multiple cloning site in pET28a (Novagen, Billerica, MA). This vector contains the λ-phosphatase gene in an operon with the cloned cDNA allowing coinduction of the kinase and λ-phosphatase. Full-length mouse Rem2 cDNA and its deletion and point mutants were subcloned in-frame with the coding sequence of the MBP present in the pMAL-c5x vector (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The vector was modified to contain a tobacco etch virus protease recognition site followed by a His6 tag between the C terminus of MBP and the N terminus of Rem2. For mammalian expression, c-myc and HA epitope tags were added in-frame to the N-terminal sequences of CaMKIIα and Rem2 and subcloned either into the vector pCMV (myc-CaMKIIα; Clontech) or pcDNA3.1 (HA-Rem2; Invitrogen).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GE Healthcare) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin, and 2 mm glutamine. Once ∼70% confluence was reached, cells were transfected with 130 ng of cDNA/cm2 for each plasmid using the calcium phosphate method. Primary neuronal cultures were prepared by coating coverslips with poly-d-lysine (20 μg/ml) and laminin (3.4 μg/ml) in 24-well plates before hippocampal neurons from embryonic day 18 rat embryos were dissected, dissociated, and plated on top of an astrocyte feeder layer. Neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (Thermo Fisher) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Neurons were transfected using the calcium phosphate method 2 days after plating (day in vitro 2 (DIV 2)).

Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

HEK293T cells were harvested 24–48 h after transfection and lysed for 20 min at 4 °C with a gentle lysis buffer (25 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 0.1% Triton X-100) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (cOmplete Mini, Roche Diagnostics). Pierce anti-HA magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA) were used to perform coimmunoprecipitations. Input samples were collected prior to mixing cell lysates with prewashed magnetic beads for 30 min at room temperature. After mixing, the beads were washed three times with 1× TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 detergent (TBS-T), 1 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm CaCl2. One final wash was done with deionized water also containing 1 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm CaCl2 before eluting with 3× sample buffer and boiling at 95 °C for 5–10 min.

The hippocampi of P14–17 mice were dissected and homogenized in 50 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 250 mm NaCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm MgCl2, and 0.1% Triton X-100 containing a protease inhibitor mixture. After 30-min incubation at 4 °C, the sample was centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and mixed with 4 μg of goat anti-Rem2 (sc-160722, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) overnight at 4 °C. Next, 25 μl of prewashed protein G magnetic beads (88847, Thermo Fisher) was added, and the sample was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. After mixing, the beads were washed three times with the lysis buffer and eluted with 2× Laemmli buffer.

Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blotting was performed using the following primary antibodies: anti-myc (antibody 2278, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-HA (sc-805-G, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phospho-CaMKIIα (Thr-286) (AP0255, Abclonal, Woburn, MA), anti-CaMKIIα (antibody 50049, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Rem2 (Cocalico Biologicals) (16), anti-phospho-GSK-3α/β (Ser-21/9) (antibody 9337, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-GSK-3α (antibody 9338, Cell Signaling Technology). Western blots were developed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE) and the following secondary antibodies from LI-COR Biotechnology (IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse (925-32210), IRDye 800W goat anti-rabbit (925-32211), and IRDye 680RD goat anti-rabbit (925-68071)) or Rockland Antibodies (donkey anti-goat DyLight 680 (605-744-002)).

Protein expression and purification

Human CaMKIIα or -δ (tagged with His6 in the N terminus) and λ-phosphatase were coexpressed in E. coli (BL21*(DE3) pRARE2lacIQ), and protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were grown overnight at room temperature, and pellets were resuspended in buffer A (50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mm sodium chloride, 1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 5% glycerol, and 0.1% Triton X-100) containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (cOmplete Mini). Chicken egg white lysozyme was added to a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and the cells were incubated on ice for 20 min. Deoxycholate and sodium chloride were added to a final concentration of 0.2% and 650 mm, respectively. Cells were sonicated using a microtip sonicator to reduce viscosity. Imidazole was added to a final concentration of 20 mm. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min, the supernatant was loaded onto a 0.5-ml Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 40 column volumes of buffer A containing 500 mm NaCl and 50 mm imidazole. CaMKII was eluted in buffer A containing 0.5 m imidazole. The eluted sample was then loaded on a HiPrep Sephacryl S-300 HR column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 25 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm 1,4-dithio-d-threitol (DTT), 5% glycerol, 0.01% Triton X-100, and 0.1 mm EDTA. Fractions containing the holoenzyme were pooled and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter unit (10,000 molecular weight cutoff) (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining. WT Rem2 and mutants were expressed in E. coli (BL21*(DE3)) as an N-terminal fusion to MBP. 2 ml of an overnight culture in 2× YT medium containing 0.2% glucose and 50 μg/ml kanamycin was further inoculated into 400 ml of the same medium, and cells were grown at 37 °C until the A600 reached 0.6. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 1 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and the cells were cultured overnight at room temperature. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in 10 ml of a solution containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, and 5% glycerol (buffer R) supplemented with a mixture of protease inhibitors (cOmplete Mini). Chicken egg white lysozyme was added to a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and the cells were incubated at 4 °C for 20 min. NaCl and Triton X-100 were added to a final concentration of 650 mm and 0.1%, respectively, and the cells were lysed by sonication. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min, the supernatant was mixed with 500 μl of amylose-agarose resin and incubated at 4 °C for 3 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The resin was washed three times with 10 ml of buffer R supplemented with 350 mm NaCl. The amylose resin was treated with tobacco etch virus protease overnight at 4 °C, and the supernatant was further purified using a nickel-Sepharose column (Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow). The protein of interest was eluted using buffer R supplemented with 500 mm imidazole, and the sample was dialyzed for 20 h at 4 °C against buffer R. CaM was purified from bovine brain using a modified version of the method described previously (51).

Electron microscopy

For the negative stain, 3.5 μl of 0.3–1 μm CaMKII was applied to 400-mesh copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) that were glow-discharged for 30 s at −20 mA immediately before use. The sample was allowed to adsorb for 1 min, then blotted, rinsed, and blotted twice with double distilled H2O. Finally, grids were stained with 0.75% uranyl formate for 1 min. Grids were imaged on an FEI Morgagni transmission microscope at 80 keV at a nominal magnification of ×44,000.

Rem2 affinity pulldown assay

Rem2 interactors expressed in the brain were identified using MBP-Rem2 immobilized on amylose-agarose beads. Brains from P14 rats were isolated and homogenized in 50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, and 5% glycerol (buffer L) containing a mixture of protease inhibitors and 0.1% Triton X-100. The lysate was incubated at 4 °C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was saved and incubated with MBP-Rem2/amylose-agarose beads for 3 h at 4 °C. Next, the beads were washed three times for 5 min with buffer L supplemented with 350 mm NaCl, and MBP-Rem2 was eluted with buffer L containing 10 mm maltose. A parallel experiment was conducted using amylose-agarose beads containing only the MBP tag to serve as a control. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using a precast 10% Bis-Tris gel (NuPAGE, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 50 mm MOPS, 50 mm Tris base, 0.1% SDS, and 1 mm EDTA (pH 7.7) as running buffer. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, and bands present in the MBP-Rem2 sample only were cut and sent for further purification and identification by microcapillary LC/tandem MS (Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA).

CaMKII activity assays

The kinase activity of CaMKII was assessed using a continuous spectrophotometric assay (34). The method is based on the coupling of the phosphorylation of peptides by CaMKII/MgATP to the oxidation of NADH via pyruvate kinase, phosphoenolpyruvate, and lactate dehydrogenase (PK/LDH assay). Monitoring the decrease in absorbance of NADH at 340 nm permits the continuous spectrophotometrical analysis of CaMKII kinase activity. The standard assay (150 μl total volume) contained 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 3.33 μm CaM, 400 μm sodium ATP, 200 μm phosphoenolpyruvate, 400 μm NADH, 9–15 units of pyruvate kinase, and 13.5–21 units of lactate dehydrogenase. The substrate peptides used were either syntide-2 (PLARTLSVAGLPGKK) or autocamtide-2 (KKALRRQETVDAL), both at 200 μm. The substrate peptides and the peptide corresponding to amino acids 68–88 of mouse Rem2 (GSMPVPYKHQLRRAQAVDELD) were obtained from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). The reaction was started by the addition of 20 nm CaMKII (monomer concentration), and the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm at room temperature was monitored in a microplate spectrophotometer (Infinite 200 Pro, Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland). Full-length human CaMKIIα and -δ were purified as described above. Rat truncated CaMKIIα was obtained from New England Biolabs. A calibration curve was used to convert the NADH absorbance readings at 340 nm into moles of ATP based on the 1:1 coupling of NADH:ATP consumption of the PK/LDH assay. Subsequently, the moles of ATP consumed in each step were used to construct a cumulative plot of ATP consumption. The kinase activity in pmol/s was calculated from the slopes of this plot. Because two kinetically distinct phases were observed in all plots, a multiple linear regression was fitted to the data points. The value of the intersection point of the two regression lines was the same for all curves for a given condition. The values obtained from the late kinetic phase were used. Importantly, a similar inhibition by Rem2 was obtained if the values from the early phase were used instead.

Phosphorylation of full-length protein by CaMKII was probed using recombinant human GSK-3α (ab42597, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (52). GSK-3α (300 ng) was added to a solution containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 3.33 μm CaM, and 400 μm sodium ATP in the presence or absence of 500 nm Rem2. The reaction was started by addition of CaMKII (20 nm final) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After incubation, the reaction was stopped by addition of 4× Laemmli buffer, and the extent of protein phosphorylation was monitored by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using a phospho-GSK3-α antibody. Samples that did not contain sodium ATP were used as negative controls.

Autonomous CaMKII

To obtain autonomous CaMKII activity (i.e. Ca2+-independent kinase activity), the purified enzyme (60 nm) was preincubated with sodium ATP (500 μm) and CaM (10 μm) in 50 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5) containing 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, and 2 mm MgCl2 in a total volume of 50 μl. After 2 min, 6 μl of 100 mm sodium EGTA was added to stop the autophosphorylation of CaMKII. The reaction mixture was immediately added to 96 μl of a solution containing 200 μm syntide-2, 400 μm NADH, 200 μm phosphoenolpyruvate, 500 μm sodium ATP, 40 μm GDP-β-S, 9–15 units of pyruvate kinase, and 13.5–21 units of lactate dehydrogenase in 50 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5) containing 150 mm NaCl. Addition of sodium EGTA lowered the final concentration of free Ca2+ to <20 nm while decreasing the free Mg2+ to ∼1.2 mm (calculated with the software MaxChelator (53)). To assure that addition of EGTA allowed only the detection of autonomous CaMKII activity, samples were run with EGTA present during the preincubation. Accordingly, at those divalent concentrations, no Ca2+/CaM-dependent activity could be detected.

Radioactive in vitro kinase assays

The kinase activity of CaMKIIα was monitored by measurement of the incorporation of radiolabeled phosphate from [γ-32P]ATP into the substrate peptide syntide-2. The kinase assay (150 μl total volume) contained 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 3.33 μm CaM, 400 μm [γ-32P]ATP (∼0.8 Ci/mmol), 200 μm syntide-2 peptide, and 40 μm either GDB-β-S or GMP-PCP (Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was initiated by addition of purified CaMKII (20 nm final) and incubated at room temperature for 8 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of 600 μl of 75 mm phosphoric acid, and peptide substrate was collected on Whatman P81 phosphocellulose paper using a slot-blot apparatus (Bio-Rad). After additional washes with 75 mm phosphoric acid, the paper was rinsed in acetone, dried, and exposed to a phosphorimaging plate. Incorporated radioactivity in each of the samples (slots) was measured using a phosphorimaging system (Typhoon FLA 7000, GE Healthcare). The radioactive incorporation was quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

CaMKII autophosphorylation

CaMKII autophosphorylation was assessed either by measurement of the incorporation of radiolabeled phosphate from [γ-32P]ATP or by slot-blot analysis using an antibody specific for CaMKIIα phosphorylated at Thr-286. The radioactive assay contained 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 3.33 μm CaM, 100 μm [γ-32P]ATP (∼16 Ci/mmol), and 40 μm GMP-PCP. The reaction was initiated by addition of CaMKII (80 nm final) and incubated at 30 °C for 2 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of 4× Laemmli loading buffer (Amresco, Solon, OH) followed by incubation at 90 °C for 2 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was blotted onto a Whatman 1 filter paper and dried. Radioactivity of protein bands was measured using a phosphorimaging system (Typhoon FLA 7000). The slot-blot assay contained 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 3.33 μm CaM in a total volume of 150 μl. When included in the reaction mixture, ATP and Rem2 were present at 500 μm and 500 nm, respectively. All reactions were started by addition of CaMKIIα to a final concentration of 20 nm (monomer). After 2-min incubation at room temperature, the reaction mixture was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane inserted in a slot-blot manifold. After washes with TBS, the membrane was subjected to a standard immunoblotting protocol using an anti-phospho-CaMKIIα Thr-286 antibody (AP0255, Abclonal).

Analysis of neuronal morphology and immunostaining

Neurons were transfected on DIV 2 with a pCMV-GFP plasmid (500 ng/well) to visualize cell morphology along with one or several of the following plasmids: pCMV-myc (control; 100 ng/well), pSuper-shRNA-Rem2 (Rem2 KD; 33 ng/well), pCMV-myc-Rem2 (Rem2 OE; 100 ng/well), or pCMV-myc-Rem2RR/GG (Rem2RR/GG OE; 100 ng/well). These neurons were fixed on DIV 11–14 with 4% paraformaldehyde + 4% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 8 min at room temperature followed by three washes with PBS. Images were acquired in a blinded manner using an Olympus Fluoview 300 confocal microscope (20× objective) and assayed for dendritic complexity by Sholl analysis.

To measure expression levels of Rem2 and Rem2RR/GG in dendrites, coverslips containing neurons were fixed and immunostained using a primary antibody against myc (1:200; 2278S, Cell Signaling Technology) diluted in gelatin blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the coverslips were washed three times for 5 min with PBS and incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to Cy3 (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature followed by three washes with PBS. Expression levels were determined by first making sum projections from individual z-stacks with ImageJ. Next, a region of interest was drawn around two random, separate stretches of dendrite per neuron in the GFP channel, and fluorescence intensity was measured in the myc channel. Myc intensity was normalized by area for every region of interest.

Calcium imaging

HEK293T cells stably expressing the mouse Cav2.1 subunit (Addgene 26578), the rat α2δ1 subunit (Addgene 26575), and the rat β4 subunit (Addgene 107426) were created using the sleeping beauty transposase system (54). The transposase system plasmids used were pSBbi-GB (Addgene 60520 for Cav2.1), pSBbi-pur (Addgene 60523 for β4), and pSBbi-hyg (Addgene 60524 for α2δ1). The cells were transfected with a vector encoding the red fluorescent protein tdTomato and either a control vector or vectors encoding for WT Rem2 or Rem2RR/GG. After 24 h, the cells were transferred to Tyrode's solution containing 0.1% BSA and 2 μm Fluo-4 AM and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The dye loading solution was removed, and the coverslip was washed three times with Tyrode's solution. Next, the coverslip was mounted on an imaging chamber and Fluo-4 fluorescence images were acquired on an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope using a 60× 1.25 numerical aperture objective (Olympus UPlanFi) and a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Orca R2, Hamamatsu) controlled by Volocity 3D Image Analysis software (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Fluorophore excitation was achieved using a mercury lamp, and spectral separation for excitation and emission was obtained using a Fluo-4 filter set (Chroma Technology). Calcium transients were evoked by perfusion of a modified Tyrode's solution containing 90 mm KCl.

Data and statistical analysis

Quantification of protein and peptide bands from digitized images of slot-blots, gels, and membranes were performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Data processing and analysis were performed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), OriginPro 8 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA), and Graph Pad Prism 7 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was determined using one-way or two-way ANOVA, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, or Student's t test as indicated in each figure legend. The confidence interval was set to 99% for all analyses except for Fig. S2 (95%). To estimate the IC50 of CaMKIIα inhibition by Rem2, the data points shown in Fig. 2F were fitted using a log(inhibitor) versus response equation.

| (Eq. 1) |

where a and b are constants.

Author contributions

L. R., J. J. H., and M. T. M. conceptualization; L. R., J. J. H., M. T. M., and S. P. formal analysis; L. R., J. J. H., K. K., B. T., J. C. C., M. T. M., and S. P. investigation; L. R., M. T. M., and S. P. methodology; L. R., J. J. H., M. T. M., and S. P. writing-original draft; L. R., J. J. H., K. K., B. T., J. C. C., M. T. M., and S. P. writing-review and editing; M. T. M. and S. P. resources; M. T. M. and S. P. supervision; M. T. M. and S. P. funding acquisition; M. T. M. and S. P. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Leslie C. Griffith for critical comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Stephen Van Hooser and members of the Paradis and Marr laboratories for resources and discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01NS065856 (to S. P.), R21NS102661 (to M. T. M. and S. P.), and R01GM117034 (to M. T. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4 and supporting statistical analysis for each figure.

- CaMKII

- Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CaM

- calmodulin

- GDP-β-S

- guanosine 5′-[β-thio]diphosphate

- GMP-PCP

- guanosine 5′-[(β,γ)-methyleno]triphosphate

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- PK/LDH

- pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase

- KD

- knockdown

- RR/GG

- R79G/R80G

- DIV

- days in vitro

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- OE

- overexpression

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Lisman J., Yasuda R., and Raghavachari S. (2012) Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long-term potentiation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 169–182 10.1038/nrn3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hudmon A., and Schulman H. (2002) Neuronal CA2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: the role of structure and autoregulation in cellular function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 473–510 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stratton M. M., Chao L. H., Schulman H., and Kuriyan J. (2013) Structural studies on the regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 292–301 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coultrap S. J., and Bayer K. U. (2012) CaMKII regulation in information processing and storage. Trends Neurosci. 35, 607–618 10.1016/j.tins.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barria A., Muller D., Derkach V., Griffith L. C., and Soderling T. R. (1997) Regulatory phosphorylation of AMPA-type glutamate receptors by CaM-KII during long-term potentiation. Science 276, 2042–2045 10.1126/science.276.5321.2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bers D. M., and Grandi E. (2009) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulation of cardiac ion channels. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 54, 180–187 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181a25078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun P., Enslen H., Myung P. S., and Maurer R. A. (1994) Differential activation of CREB by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type II and type IV involves phosphorylation of a site that negatively regulates activity. Genes Dev. 8, 2527–2539 10.1101/gad.8.21.2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lisman J., and Raghavachari S. (2015) Biochemical principles underlying the stable maintenance of LTP by the CaMKII/NMDAR complex. Brain Res. 1621, 51–61 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhabotinsky A. M. (2000) Bistability in the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-phosphatase system. Biophys. J. 79, 2211–2221 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76469-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mullasseril P., Dosemeci A., Lisman J. E., and Griffith L. C. (2007) A structural mechanism for maintaining the ‘on-state’ of the CaMKII memory switch in the post-synaptic density. J. Neurochem. 103, 357–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang B. H., Mukherji S., and Soderling T. R. (2001) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II inhibitor protein: localization of isoforms in rat brain. Neuroscience 102, 767–777 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00520-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang B. H., Mukherji S., and Soderling T. R. (1998) Characterization of a calmodulin kinase II inhibitor protein in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 10890–10895 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghiretti A. E., Moore A. R., Brenner R. G., Chen L. F., West A. E., Lau N. C., Van Hooser S. D., and Paradis S. (2014) Rem2 is an activity-dependent negative regulator of dendritic complexity in vivo. J. Neurosci. 34, 392–407 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1328-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore A. R., Richards S. E., Kenny K., Royer L., Chan U., Flavahan K., Van Hooser S. D., and Paradis S. (2018) Rem2 stabilizes intrinsic excitability and spontaneous firing in visual circuits. Elife 7, e33092 10.7554/eLife.33092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghiretti A. E., Kenny K., Marr M. T. 2nd, and Paradis S. (2013) CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of the GTPase Rem2 is required to restrict dendritic complexity. J. Neurosci. 33, 6504–6515 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3861-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghiretti A. E., and Paradis S. (2011) The GTPase Rem2 regulates synapse development and dendritic morphology. Dev. Neurobiol. 71, 374–389 10.1002/dneu.20868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buraei Z., and Yang J. (2015) Inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels by RGK proteins. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 8, 180–187 10.2174/1874467208666150507105613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang T., and Colecraft H. M. (2013) Regulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by RGK proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828, 1644–1654 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Correll R. N., Pang C., Niedowicz D. M., Finlin B. S., and Andres D. A. (2008) The RGK family of GTP-binding proteins: regulators of voltage-dependent calcium channels and cytoskeleton remodeling. Cell. Signal. 20, 292–300 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flynn R., and Zamponi G. W. (2010) Regulation of calcium channels by RGK proteins. Channels 4, 434–439 10.4161/chan.4.6.12865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abiria S. A., and Colbran R. J. (2010) CaMKII associates with CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels via selected β subunits to enhance regulatory phosphorylation. J. Neurochem. 112, 150–161 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06436.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jenkins M. A., Christel C. J., Jiao Y., Abiria S., Kim K. Y., Usachev Y. M., Obermair G. J., Colbran R. J., and Lee A. (2010) Ca2+-dependent facilitation of Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels by densin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Neurosci. 30, 5125–5135 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4367-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang X., Lautermilch N. J., Watari H., Westenbroek R. E., Scheuer T., and Catterall W. A. (2008) Modulation of CaV2.1 channels by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II bound to the C-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 341–346 10.1073/pnas.0710213105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magupalli V. G., Mochida S., Yan J., Jiang X., Westenbroek R. E., Nairn A. C., Scheuer T., and Catterall W. A. (2013) Ca2+-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II bound to the C-terminal domain of CaV2.1 calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 4637–4648 10.1074/jbc.M112.369058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bayer K. U., Löhler J., Schulman H., and Harbers K. (1999) Developmental expression of the CaM kinase II isoforms: ubiquitous γ- and δ-CaM kinase II are the early isoforms and most abundant in the developing nervous system. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 70, 147–154 10.1016/S0169-328X(99)00131-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Finlin B. S., Shao H., Kadono-Okuda K., Guo N., and Andres D. A. (2000) Rem2, a new member of the Rem/Rad/Gem/Kir family of Ras-related GTPases. Biochem. J. 347, 223–231 10.1042/bj3470223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reymond P., Coquard A., Chenon M., Zeghouf M., El Marjou A., Thompson A., and Ménétrey J. (2012) Structure of the GDP-bound G domain of the RGK protein Rem2. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 68, 626–631 10.1107/S1744309112013541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sasson Y., Navon-Perry L., Huppert D., and Hirsch J. A. (2011) RGK family G-domain:GTP analog complex structures and nucleotide-binding properties. J. Mol. Biol. 413, 372–389 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Correll R. N., Botzet G. J., Satin J., Andres D. A., and Finlin B. S. (2008) Analysis of the Rem2-voltage depandant calcium channel β subunit interaction and Rem2 interaction with phosphorylated phosphatidylinositide lipids. Cell. Signal. 20, 400–408 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Béguin P., Mahalakshmi R. N., Nagashima K., Cher D. H., Kuwamura N., Yamada Y., Seino Y., and Hunziker W. (2005) Roles of 14-3-3 and calmodulin binding in subcellular localization and function of the small G-protein Rem2. Biochem. J. 390, 67–75 10.1042/BJ20050414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flynn R., Labrie-Dion E., Bernier N., Colicos M. A., De Koninck P., and Zamponi G. W. (2012) Activity-dependent subcellular cotrafficking of the small GTPase Rem2 and Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase IIα. PLoS One 7, e41185 10.1371/journal.pone.0041185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ochiishi T., Terashima T., and Yamauchi T. (1994) Specific distribution of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α and β isoforms in some structures of the rat forebrain. Brain Res. 659, 179–193 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90877-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chao L. H., Pellicena P., Deindl S., Barclay L. A., Schulman H., and Kuriyan J. (2010) Intersubunit capture of regulatory segments is a component of cooperative CaMKII activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 264–272 10.1038/nsmb.1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kiianitsa K., Solinger J. A., and Heyer W. D. (2003) NADH-coupled microplate photometric assay for kinetic studies of ATP-hydrolyzing enzymes with low and high specific activities. Anal. Biochem. 321, 266–271 10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00461-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bostrom S. L., Dore J., and Griffith L. C. (2009) CaMKII uses GTP as a phosphate donor for both substrate and autophosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 390, 1154–1159 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jiao Y., Jalan-Sakrikar N., Robison A. J., Baucum A. J. 2nd, Bass M. A., and Colbran R. J. (2011) Characterization of a central Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα/β binding domain in densin that selectively modulates glutamate receptor subunit phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24806–24818 10.1074/jbc.M110.216010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hashimoto Y., Schworer C. M., Colbran R. J., and Soderling T. R. (1987) Autophosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Effects on total and Ca2+-independent activities and kinetic parameters. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 8051–8055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vest R. S., Davies K. D., O'Leary H., Port J. D., and Bayer K. U. (2007) Dual mechanism of a natural CaMKII inhibitor. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 5024–5033 10.1091/mbc.e07-02-0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Strack S., Robison A. J., Bass M. A., and Colbran R. J. (2000) Association of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II with developmentally regulated splice variants of the postsynaptic density protein densin-180. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25061–25064 10.1074/jbc.C000319200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fink C. C., Bayer K. U., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E. Jr, Schulman H., and Meyer T. (2003) Selective regulation of neurite extension and synapse formation by the β but not the α isoform of CaMKII. Neuron 39, 283–297 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00428-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ghiretti A. E., and Paradis S. (2014) Molecular mechanisms of activity-dependent changes in dendritic morphology: role of RGK proteins. Trends Neurosci. 37, 399–407 10.1016/j.tins.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moore A. R., Ghiretti A. E., and Paradis S. (2013) A loss-of-function analysis reveals that endogenous Rem2 promotes functional glutamatergic synapse formation and restricts dendritic complexity. PLoS One 8, e74751 10.1371/journal.pone.0074751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paradis S., Harrar D. B., Lin Y., Koon A. C., Hauser J. L., Griffith E. C., Zhu L., Brass L. F., Chen C., and Greenberg M. E. (2007) An RNAi-based approach identifies molecules required for glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse development. Neuron 53, 217–232 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chao L. H., Stratton M. M., Lee I. H., Rosenberg O. S., Levitz J., Mandell D. J., Kortemme T., Groves J. T., Schulman H., and Kuriyan J. (2011) A mechanism for tunable autoinhibition in the structure of a human Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II holoenzyme. Cell 146, 732–745 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stratton M., Lee I. H., Bhattacharyya M., Christensen S. M., Chao L. H., Schulman H., Groves J. T., and Kuriyan J. (2014) Activation-triggered subunit exchange between CaMKII holoenzymes facilitates the spread of kinase activity. Elife 3, e01610 10.7554/eLife.01610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mayford M., Wang J., Kandel E. R., and O'Dell T. J. (1995) CaMKII regulates the frequency-response function of hippocampal synapses for the production of both LTD and LTP. Cell 81, 891–904 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90009-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. De Koninck P., and Schulman H. (1998) Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science 279, 227–230 10.1126/science.279.5348.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin Y. C., and Redmond L. (2008) CaMKIIβ binding to stable F-actin in vivo regulates F-actin filament stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15791–15796 10.1073/pnas.0804399105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Redmond L., and Ghosh A. (2005) Regulation of dendritic development by calcium signaling. Cell Calcium 37, 411–416 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kenny K., Royer L., Moore A. R., Chen X., Marr M. T. 2nd, and Paradis S. (2017) Rem2 signaling affects neuronal structure and function in part by regulation of gene expression. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 85, 190–201 10.1016/j.mcn.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gopalakrishna R., and Anderson W. B. (1982) Ca2+-induced hydrophobic site on calmodulin: application for purification of calmodulin by phenyl-Sepharose affinity chromatography. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 104, 830–836 10.1016/0006-291X(82)90712-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Song B., Lai B., Zheng Z., Zhang Y., Luo J., Wang C., Chen Y., Woodgett J. R., and Li M. (2010) Inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3 by CaMKII couples depolarization to neuronal survival. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41122–41134 10.1074/jbc.M110.130351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bers D. M., Patton C. W., and Nuccitelli R. (2010) A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+ buffers. Methods Cell Biol. 99, 1–26 10.1016/B978-0-12-374841-6.00001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kowarz E., Löscher D., and Marschalek R. (2015) Optimized Sleeping Beauty transposons rapidly generate stable transgenic cell lines. Biotechnol. J. 10, 647–653 10.1002/biot.201400821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.