Abstract

Study Design:

Prospective longitudinal study.

Objective:

To determine the association between baseline patient activation and participation in postoperative physical therapy in a cohort of individuals after lumbar spine surgery.

Summary of Background Data:

The Patient Activation Measure is a recently developed tool to assess patient activation. Patient activation is defined as an individual’s propensity to engage in adaptive health behavior that may, in turn, lead to improved patient outcomes. It has not previously been used in spine research.

Methods:

We assessed baseline patient activation levels in individuals presenting for surgery of the lumbar spine via the Patient Activation Measure. Differences in patient characteristics across patient-activation quartiles were assessed using analysis of variance. After surgery, we assessed attendance (self-reported weekly) and engagement in physical therapy (at the last visit, using the Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale) and determined the ratio of sessions attended to sessions prescribed. The influence of baseline patient activation, in the setting of other patient characteristics, to predict attendance and engagement with physical therapy was examined using linear regression methods.

Results:

Scores on the Patient Activation Measure were positively correlated with participation (r = 0.53) and engagement (r = 0.75) in physical therapy. Individuals with low activation were more likely to report low self-efficacy for physical therapy, low hope, and external locus of control compared with those with high activation.

Conclusion:

Increased patient activation is associated with improved adherence with physical therapy as reflected in attendance and engagement.

Keywords: patient activation, functional recovery, physical therapy, lumbar spine surgery

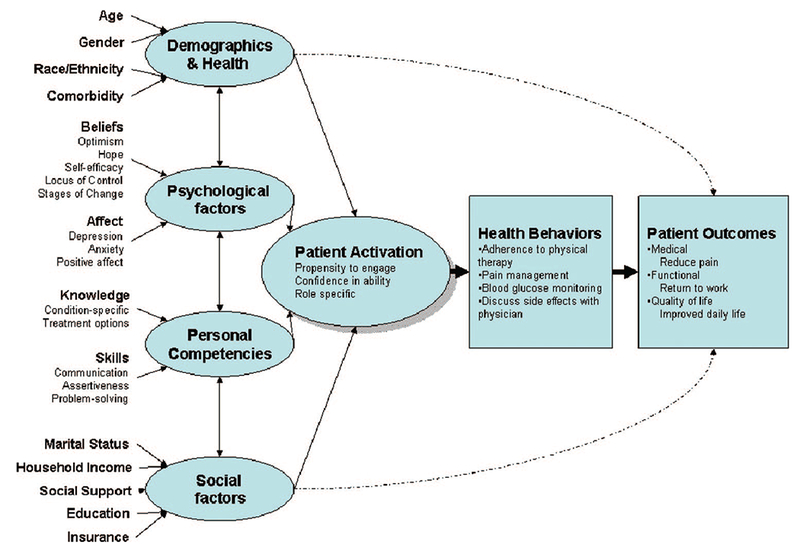

The North American Spine Society has recommended postoperative physical therapy after surgery for degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine.1 For most patients, the back muscles have been weakened from preoperative deconditioning2 or as a result of surgical incisions through muscle groups.3 A major goal of physical therapy, therefore, is to retrain muscles, increase strength, and improve endurance. Patient factors that influence adherence to physical therapy after lumbar spine surgery include presence of depressive symptoms and attitudes, such as motivation to participate in physical therapy. Patient activation, defined as an individual’s propensity to engage in adaptive health behavior that may, in turn, lead to improved outcomes, emerges from the influence of psychological factors and personal competencies.

The role that patient activation has in determining adherence to physical therapy has not been documented. Variation in adherence is related to a patient’s motivation and attitudes toward the utility of physical therapy.4 Patients who consider physical therapy as an important means of recovering function after surgery are more motivated to participate.5 Psychological factors may explain the observed variability in adherence; however, they have generally been studied in isolation. Health behavior has often focused primarily on negative factors, such as depression and anxiety. More recently, the role that positive psychological factors, such as optimism, hope, self-efficacy, and locus of control, may play is being explored. Patient activation assesses the influence of these psychological factors and personal competencies, such as condition-specific knowledge, on health behavior.6 An activated patient is one who is armed with the skills, knowledge, and motivation to be an effective member of the healthcare team.7

The objective of the current study was to determine the association between baseline patient activation and participation in postoperative physical therapy in a cohort of individuals after lumbar spine surgery. Specifically, we have described patient activation in this population; examined the association between patient activation and other patient characteristics; and explored the relationship between patient activation and adherence to physical therapy. We hypothesized that (1) individuals undergoing lumbar spine surgery would display, as a group, a range of patient activation similar to that of other populations; (2) there would be a positive association between positive psychological factors and adherence to physical therapy; (3) there would be a positive association between patient activation and psychological factors; and (4) patient activation would provide additional information regarding an individual’s propensity to adhere to physical therapy beyond that obtained from traditional psychological measures.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Individuals presenting to our academic spine center between August 2005 and May 2006 for surgical treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis were eligible for inclusion in this prospective cohort study. Inclusion criteria were: age >18 years, English-speaking, and the ability to provide informed consent, as determined by a Mini-Mental Status Examination score of >18 of 30.8 Because individuals who have undergone previous spine surgery have a markedly different clinical recovery course than those having primary surgery,9 such patients (based on a review of the medical records) were excluded. Of the 66 eligible participants, 1 refused to participate, resulting in a study population of 65 predominantly non-Hispanic white (89%) and female (58%) individuals with a mean age of 58 years (SD 15 years). The current study has been reviewed and approved by our center’s Institutional Review Board.

Participant Assessment

Individual participants were enrolled and baseline assessment was conducted before surgery. The baseline assessment included questions concerning demographic (age, gender, and race/ethnicity), health (presence of comorbid conditions), and social (education and household income) characteristics. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, a well-validated means of risk adjustment for in-hospital complications and mortality, was used to assess the presence of comorbid conditions.10,11 All research-related events occurred in a private research room to ensure confidentiality.

Measuring Adherence

Adherence was defined operationally with measures of attendance and engagement. Attendance was based on self-report assessments collected weekly through week 6. This assessment consisted of response to 2 questions: (1) how many sessions of physical therapy were prescribed for you in the past 7 days? and (2) how many sessions of physical therapy did you attend in the past 7 days? Participants called an answering machine to record their response to these 2 questions. If a response was not recorded, the research staff contacted the participant to collect this information. Attempts to reach the participant via the telephone were repeated until successful. The timeliness of this assessment provided some protection against recall bias. An overall average attendance was computed for the 6 weeks.

Engagement was based on assessments collected at week 6. Using the Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale, the physical therapist rated the degree of engagement exhibited by the participant. This instrument is a 5-item Likert scale used to rate behavioral observations of the patient during physical therapy. The physical therapist is asked to rate the patient’s attendance, the patient’s attitude toward physical therapy, the need for prompts (either verbal or physical), the patient’s understanding of the importance of physical therapy, and the patient’s level of activity during physical therapy.12 This tool, which has been used to measure engagement in rehabilitative therapy for individuals with spinal cord injuries, stroke, amputations, and hip or knee replacement, was established in a previous study as a consistent (Cronbach α >0.90) and reliable (test-retest 0.73) measure of engagement.12 Evidence for its validity was established through correlation with key clinical indicators.

Measuring Patient Activation

Patient activation has been operationally defined as an individual’s propensity to engage in positive health behavior. A recently published study examined the association between patient activation and health behavior in a group of individuals with a variety of chronic diseases.13 In that study, survey respondents provided information regarding patient activation and measures related to health behaviors and outcomes. Individuals with high activation were more likely to endorse the use of self-management services and to have increased medication adherence than individuals with low activation. Patient activation was assessed using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (Table 1).6 The PAM is a participant-completed 13-item questionnaire that addresses key psychological factors and personal competencies. The scale used in our study is a modification of the original that was devised to increase the clinical utility of the measure.14 Validity of the scale has been established through correlation with key clinical indicators, such as overall health status and self-management behaviors.14 Participants are asked to rate their agreement on individual test items ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Scores on the PAM are continuous measures ranging from 0 (no activation) to 100 (high activation). Previous reports of the use of this questionnaire have shown observed scores between 40 and 80 points (average, 55 points).6 The use of the PAM in a cohort of individuals about to undergo surgery for low back pain has been shown to provide a reliable (intraclass coefficient of 0.87) and valid assessment of patient activation (Skolasky RL, Riley III LH, Wegener ST, MacKenzie E. Psychometric properties of the Patient Activation Measure in persons undergoing spine surgery. Manuscript in preparation).2

Table 1.

Patient Activation Measure

| Stage* | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | When all is said and done, I am the person who is responsible for managing my health condition. |

| 2 | Taking an active role in my own health care is the most important factor in determining my health and ability to function. | |

| II | 3 | I am confident that I can take actions that will help prevent or minimize some symptoms or problems associated with my health condition. |

| 4 | I know what each of my prescribed medications do. | |

| 5 | I am confident that I can tell when I need to go get medical care and when I can handle a health problem myself. | |

| 6 | I am confident that I can tell a doctor concerns I have even when he or she does not ask. | |

| 7 | I am confident that I can follow through on medical treatments I need to do at home. | |

| 8 | I understand the nature and causes of my health conditions. | |

| III | 9 | I know the different medical treatment options available for my health condition. |

| 10 | I have been able to maintain lifestyle changes for my health condition that I have made. | |

| 11 | I know how to prevent further problems with my health condition. | |

| IV | 12 | I am confident that I can figure out solutions when new situations or problems arise with my health condition. |

| 13 | I am confident that I can maintain lifestyle changes, like diet and exercise, even during times of stress. |

Above are statements that people sometimes make when asked about their health. Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with each statement as it applies to you personally. Your answers should be “true for you” and not what you think your doctor wants you to say.

Stages of activation include: I, believes taking an active role is important; II, confidence and knowledge to take action; III, taking action; and IV, staying the course under stress. Modified with permission from Health Serv Res 2005;40:1918–30.

Psychological Factors

Information was collected using well-validated instruments regarding the psychological factors. Optimism was measured using the Life Orientation Test – Revised, a 6-item Likert type scale designed to assess optimism on a continuous scale.15,16 Individuals are presented with positive statements, such as “I am always optimistic about my future,” and negative statements, such as “If something can go wrong, it will.” This measure has previously been shown to be reliable and valid with acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.76).15,17,18

The Trait Hope Scale is a 12-item instrument on which participants rate their responses to items on a 4-point Likert scale. This measure has been shown to be reliable (test-retest correlation, 0.73–0.82) in providing measures of a person’s perceived capabilities at generating workable routes to desired goals (pathway thinking) and the motivation and/or perceived capacity to reach desired goals (agency thinking).19

Self-efficacy to participate in physical therapy was measured using an instrument designed to assess an individual’s confidence to perform required exercises/tasks that was adapted from the Arthritis self-efficacy scale.20 Substantial literature documents state-dependent customized measures of self-efficacy as useful in predicting behavior.21–27

The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale is a reliable and well-validated scale that provides estimates of assignment of locus of control to internal and external forces.28 This scale is composed of 5 subcomponents: internality, physician, other people, powerful others, and chance. The internal consistency of this scale has been reported across a variety of populations to range from 0.83 to 0.86.28

The presence of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Prime MD.29 The Prime MD is a brief screening tool based on diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to identify the presence of depressive symptoms. When compared against structured interviews to determine the presence of depression, the Prime MD has good sensitivity (0.73) and specificity (0.98).29

Statistical Analyses

The goal of the current analysis was to identify and to understand the role that patient activation may have in explaining adherence to postoperative physical therapy. The 2 measures of adherence to physical therapy (attendance and engagement) were used as separate outcome measures.

The first objective was to describe patient activation for individuals about to undergo elective lumber spine surgery. We tested normality of PAM scores using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Second, we stratified the sample into quartiles based on PAM scores to examine the relationship between patient activation and other patient characteristics (demographics, health, social, and psychological factors). Continuous measures were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with planned between group comparisons.30 Categorical measures were assessed using χ2 test for independence.

Third, correlation coefficients between PAM and attendance or engagement in physical therapy were calculated. To build evidence that patient activation is uniquely associated with adherence, linear multivariate models were constructed to test the association between adherence and patient activation and other patient characteristics (demographic, health, social, and psychological factors). In building a predictive model of adherence, we chose to follow a theoretical approach. All independent variables with scientific rationale to expect an association with adherence were included. After model construction, our measure of patient activation was added as a final predictor. The significance of the parameter estimate and the change in the amount of variance explained by the model provided an estimate of patient activation’s unique predictive ability. Interactions between patient activation and other variables in the model were tested for their modifying influence. Regression diagnostics concerning colinearity and residual analysis were conducted to assess the fit of a final model.31

Results

Patient Activation: Distribution and Correlates

PAM scores followed a normal distribution with mean score of 58.49 points (SD 15.09 points; range, 32.2–100) (Shapiro-Wilk W = 0.973; P = 0.181). We characterized 16 individuals with high activation (fourth quartile) and 19 individuals with low activation (first quartile). The remaining 30 individuals were evenly divided between the second and third quartiles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biologic, Social, and Psychological Characteristics of Participant Cohort, Overall and Stratified by Patient Activation

| Patient Activation Quartile (N) [Mean (SD); Range] |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Descriptor | Overall (N = 65) | 1st (N = 19) [41.5 (4.7); 32 48] |

2nd (N = 15) [53.9 (2.6); 50 56] |

3rd (N = 15) [62.5 (2.1); 60 66] |

4th (N = 16) [79.2 (8.7); 69 100] |

P* |

| Biologic | |||||||

| Age | Mean (SD) years | 58.0 (15.4) | 60.5 (18.0) | 55.6 (16.6) | 59.9 (11.1) | 55.6 (15.4) | 0.704 |

| <45 yr | 13 (20.0%) | 2 (10.5%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (25.0%) | 0.491 | |

| 45–65 yr | 31 (47.7%) | 8 (42.1%) | 6 (40.0%) | 9 (60.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | ||

| >65 yr | 21 (32.3%) | 9 (47.4%) | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 38 (58%) | 14 (73.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | 10 (66.7%) | 8 (50.0%) | 0.187 |

| Male | 27 (42%) | 5 (26.3%) | 9 (60.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 8 (50.0%) | ||

| Race | White | 58 (89.2%) | 16 (84.2%) | 11 (73.3%) | 15 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 0.042 |

| Nonwhite | 7 (10.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 63 (96.9%) | 18 (94.7%) | 15 (100%) | 14 (93.3%) | 16 (100%) | 0.586 |

| Hispanic | 2 (3.1%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | ||

| Charlson index | Mean (SD) | 3.91 (5.22) | 4.19 (5.45) | 3.01 (2.77) | 5.53 (7.78) | 2.88 (3.52) | 0.471 |

| Social | |||||||

| Marital status | Married/living with spouse | 52 (80.0%) | 16 (84.2%) | 9 (60.0%) | 13 (86.7%) | 14 (87.4%) | 0.346 |

| Living with partner | 3 (4.6%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 4 (6.1%) | 0 | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 | ||

| Never married | 6 (9.3%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0 | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Household income | <$30 k | 7 (10.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0 | 1 (6.3%) | 0.048 |

| $30 k–$50 k | 28 (43.1%) | 11 (57.9%) | 7 (46.7%) | 7 (46.7%) | 3 (18.7%) | ||

| >$50 k | 24 (36.9%) | 3 (15.8%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 11 (68.7%) | ||

| Not reported | 6 (9.2%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Education | <College | 29 (44.6%) | 12 (63.2%) | 7 (46.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | 0.135 |

| College | 23 (35.4%) | 6 (31.6%) | 3 (20.0%) | 8 (53.3%) | 6 (37.4%) | ||

| >College | 13 (20.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | ||

| Psychological | |||||||

| Depression (Prime MD) | Mean (SD) | 1.95 (2.11) | 3.84 (2.63) | 1.60 (1.24) | 0.80 (1.01) | 1.13 (1.26) | <0.001 |

| Optimism | Mean (SD) points | 16.5 (4.0) | 15.4 (3.2) | 16.1 (5.3) | 17.8 (3.1) | 16.9 (4.2) | 0.342 |

| Hope† | Mean (SD) points | 38.6 (5.6) | 35.8 (5.3) | 38.6 (5.4) | 38.9 (4.9) | 41.4 (5.8) | 0.032 |

| Self-efficacy§ | Mean (SD) points | 69.9 (17.0) | 54.0 (12.8) | 74.0 (18.4) | 76.0 (9.5) | 79.2 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Locus of control | Mean (SD) points | ||||||

| Internal | 27.5 (5.0) | 26.8 (4.3) | 25.7 (6.4) | 28.8 (3.5) | 28.5 (5.3) | 0.279 | |

| Doctors¶ | 12.9 (3.4) | 14.9 (3.7) | 10.7 (2.3) | 12.5 (2.9) | 12.8 (3.3) | 0.003 | |

| Powerful others§ | 26.0 (5.4) | 30.0 (5.8) | 22.8 (3.0) | 24.7 (4.6) | 25.6 (4.9) | <0.001 | |

| Other people§ | 13.2 (2.7) | 15.1 (2.5) | 12.1 (2.4) | 12.2 (2.2) | 12.8 (2.7) | 0.002 | |

| Chance | 26.6 (4.5) | 28.0 (3.3) | 24.7 (6.2) | 25.8 (3.8) | 27.5 (4.1) | 0.127 | |

Comparison across quartiles assessed using analysis of variance, a priori comparisons between quartiles using Tukey multiple comparison procedure.

A priori comparisons between quartiles showed significant differences between the first and fourth quartile (P < 0.05).

A priori comparisons between quartiles showed significant differences between the first and each of the second, third, and fourth quartile (P < 0.05).

A priori comparisons between quartiles showed significant differences between the first and second quartile (P < 0.05).

There were no significant differences among quartile groups with respect to age, gender, marital status, comorbid conditions, or education (Table 2). Nonwhite individuals were more likely to score in the lower quartiles of the PAM (P = 0.042). Individuals reporting high household income were more likely to be in the upper quartiles of patient activation (P = 0.048), a finding especially apparent between the first and fourth quartile. For individuals in the lowest activation group, nearly 3 quarters reported an annual household income below $50,000, whereas in the highest activation group, nearly 69% of individuals reported an annual household income of more than $50,000.

As patient activation increased, the severity of depressive symptoms decreased (P < 0.001) (Table 2). With respect to other psychological factors, increasing activation was significantly associated with increasing self-efficacy (P < 0.001), increasing hopefulness (P = 0.032), and decreasing externalized control (powerful others, P < 0.001; physicians, P = 0.003; other people, P = 0.002).

Adherence: Distribution and Correlates

Mean attendance for the 6-week period was 76% (SD, 32%; range, 0%−100%) (Table 3). Three individuals did not attend any physical therapy sessions. Post hoc questioning indicated that 1 participant could not afford the health insurance copayment and 2 participants found it inconvenient to attend the sessions. The mean engagement score on our Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale was 22.1 points (SD, 5.2 points; range, 11–30 points). The distribution of these scores was similar to that reported in other populations of individuals with spinal cord injuries, stroke, amputation, or hip or knee replacement.12

Table 3.

Adherence to Physical Therapy (Attendance and Engagement), Overall and Stratified by Patient Activation

| Patient Activation Quartile |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure of Adherence | Overall | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | P* |

| Attendance† | ||||||

| N | 65 | 19 | 15 | 15 | 16 | |

| Mean (SD) | 75.6% (31.7%) | 55.6% (33.9%) | 63.2% (38.3%) | 93.8% (10.9%) | 94.1% (8.9%) | <0.001 |

| Range | 0%, 100% | 0%, 100% | 0%, 100% | 60%, 100% | 75%, 100% | |

| Engagement§,¶ | ||||||

| N | 62 | 18 | 13 | 15 | 16 | |

| Mean (SD) | 22.1 (5.2) | 18.8 (6.1) | 18.9 (2.2) | 23.2 (3.0) | 27.4 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Range | 11,30 | 11.1, 27 | 15, 22 | 13, 25.4 | 24, 29.8 | |

Comparison of characteristics among the quartiles were assessed using analysis of variance with a priori comparisons between quartiles using Tukey multiple comparison procedure.

A priori comparisons between quartiles showed significant differences between all quartiles (P < 0.05) with the exception of between the first and second quartile and between the third and fourth quartile.

Participants who did not attend any prescribed physical therapy sessions were not available for engagement rating using our Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale.

A priori comparisons between quartiles showed significant differences between all quartiles (P < 0.05), with the exception of the first and second quartiles.

Patient Activation and Adherence

Attendance was moderately correlated with patient activation (r = 0.53; P < 0.001) indicating that patient activation accounted for roughly 28% of variation in attendance. A strong correlation was observed between patient activation and engagement (r = 0.75; P < 0.001), suggesting that highly activated individuals were more likely to be rated as highly engaged by their physical therapists. Patient activation accounted for 56% of variation in engagement score.

Statistical models were developed to examine the association between adherence to physical therapy and patient activation, in the context of other psychological factors. These other psychological factors were used to estimate the base predictive models (model 1) for attendance (Table 4) and engagement (Table 5). These psychological measures accounted for 37% of variation in attendance and 31% of variation in engagement. To estimate the additional information provided by measuring patient activation, PAM scores were added to these models (model 2). This expansion of model 1 provided significantly greater explanation of variation in attendance [36.8%–45.2%; F (1, 55) = 9.72; P < 0.001] (Table 4). Examination of the β coefficients between model 1 and model 2 showed there were modest changes with the addition of patient activation. The largest of these changes was for self-efficacy to participate in physical therapy (12.04–9.07 points). The addition of patient activation to model 1 of engagement increased the total variance explained to 63.2% [F(1,52) = 46.47; P < 0.001] (Table 5). The parameter estimates showed large changes for self-efficacy and severity of depressive symptoms between model 1 and model 2.

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Models of Relationships Between Patient Activation and Measures of Self-reported Attendance in Physical Therapy, Adjusted for Select Biologic, Social, and Psychological Factors

| Attendance* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Predictors | β-Coefficient (SD)† | t Statistic | P | R2§ |

| 1 | Depression (Prime MD) | −2.92 (15.37) | −0.18 | 0.859 | 0.4466 |

| Optimism | 21.48 (9.11) | 2.36 | 0.022 | ||

| Hope | 4.42 (6.69) | 0.66 | 0.513 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 12.05 (2.50) | 4.81 | <0.001 | ||

| Locus of control | |||||

| Internal | 13.00 (7.31) | 1.77 | 0.078 | ||

| Chance occurrence | 7.06 (9.17) | 0.77 | 0.445 | ||

| Powerful others | −21.57 (16.28) | −1.33 | 0.191 | ||

| Doctor | −9.63 (22.97) | −0.42 | 0.675 | ||

| Other people | 0 | ||||

| 2 | Depression (Prime MD) | 18.92 (16.78) | 1.13 | 0.265 | 0.5290 |

| Optimism | 21.78 (8.48) | 2.57 | 0.013 | ||

| Hope | 7.36 (6.30) | 1.17 | 0.092 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 9.07 (2.52) | 3.60 | <0.001 | ||

| Locus of control | |||||

| Internal | 13.42 (6.81) | 1.97 | 0.049 | ||

| Chance occurrence | 3.88 (8.61) | 0.45 | 0.654 | ||

| Powerful others | −17.27 (15.22) | −1.13 | 0.261 | ||

| Doctor | 40.79 (21.58) | 1.89 | 0.064 | ||

| Other people | 0 | ||||

| Patient activation | 8.17 (2.63) | 3.10 | 0.003 | ||

Attendance was assessed using the self-reported ratio of physical therapy sessions attended to sessions prescribed, n = 65.

Parameter estimates represent change in attendance based on a 10-U change in the independent variable.

R2 is adjusted by dividing sum of square by associated degrees of freedom and estimates the variance in the dependent measure accounted for by predictors in the model

Table 5.

Multiple Linear Models of Relationships Between Patient Activation and Engagement in Physical Therapy, Adjusted for Select Biologic, Social, and Psychological Factors

| Engagement* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Predictors | β-Coefficient (SD)† | t Statistic | P | R2§ |

| 1 | Depression (Prime MD) | −7.68 (3.06) | 2.51 | 0.015 | 0.3062 |

| Optimism | 1.76 (1.73) | 1.01 | 0.315 | ||

| Hope | −1.27 (1.26) | −1.01 | 0.315 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 1.23 (0.46) | 2.65 | 0.011 | ||

| Locus of control | |||||

| Internal | 0.06 (1.41) | 0.04 | 0.964 | ||

| Chance occurrence | −0.16 (1.75) | −0.10 | 0.924 | ||

| Powerful others | −0.75 (3.06) | −0.25 | 0.806 | ||

| Doctor | −4.09 (4.28) | −0.96 | 0.344 | ||

| Other people | 0 | ||||

| 2 | Depression (Prime MD) | −0.31 (2.50) | −0.13 | 0.900 | 0.6315 |

| Optimism | 2.19 (1.28) | 1.72 | 0.091 | ||

| Hope | −2.39 (0.94) | −2.55 | 0.014 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 1.29 (0.37) | 3.49 | <0.001 | ||

| Locus of control | |||||

| Internal | 0.05 (1.04) | 0.05 | 0.959 | ||

| Chance occurrence | −1.08 (1.29) | −0.84 | 0.406 | ||

| Powerful others | 0.33 (2.26) | 0.15 | 0.885 | ||

| Doctor | 1.56 (3.17) | 0.49 | 0.625 | ||

| Other people | 0 | ||||

| Patient activation | 2.66 (0.39) | 6.78 | <0.001 | ||

Engagement was assessed using our Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale, n = 62.

Parameter estimates represent change in engagement based on a 10-U change in the independent variable.

R2 is adjusted by dividing sum of square by associated degrees of freedom and estimates the variance in the dependent measure accounted for by predictors in the model.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was threefold: (1) to describe patient activation among patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery; (2) to examine the association between patient activation and other characteristics; and (3) to explore the relationship between patient activation and adherence to postoperative physical therapy.

With regard to the first objective, we have shown that the PAM scores follow a normal distribution and have sufficient spread to stratify the cohort into meaningful subgroups.

For the second objective, individuals differ in terms of patient activation, as evidenced by the observed differences in psychological factors across the patient activation quartiles. Theory predicts that, as individuals vary in patient activation, they would also differ in other psychological factors. These factors would include those not easily changed (immutable) and those that could be changed (mutable).6 Immutable psychological factors included optimism, hope, and locus of control. Mutable psychological characteristics included presence of depressive symptoms and self-efficacy to participate in physical therapy. These mutable characteristics may serve as a potential intervention target for improving patient activation. Interventions to increase self-efficacy have been shown to be successful. Among those undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery, an empowerment model of education was shown to increase self-efficacy to participate in physical therapy.32 In our study, individuals with low activation endorsed a lower confidence to participate in physical therapy than individuals with high activation (53% vs. 79%), indicating potential for improvement.

In meeting the third objective, patient activation was significantly correlated with measures of attendance and engagement. PAM scores accounted for 28% of variance in attendance and 56% of variance in engagement when examining the unadjusted bivariate analyses. Patient activation is a property that emerges from the influence of psychological factors and personal competencies6 (Figure 1). Therefore, it was important to explore the association between patient activation and adherence in the setting of other psychological factors. Increasing self-efficacy was associated with increased attendance and engagement, and externalized locus of control was associated with decreased attendance. Multivariate linear regression models showed that patient activation was a significant predictor of adherence to physical therapy. The addition of patient activation significantly increased the amount of variance explained in these models. This increase in variation indicated that patient activation provided additional information in the prediction of adherence to physical therapy. It is possible that this increase in information may be the results of the knowledge and skills components that are included in the PAM.

Figure 1.

Development and maintenance of patient activation.

Our study has certain limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting the current findings. First, the study design did not follow individuals through to functional recovery, preventing us from making direct inferences about the influence of patient activation on recovery. However, given the importance of adoption of positive health behaviors after surgery,33 our study supports the influence of patient activation on a surrogate marker of functional recovery.

Second, our sample was drawn from 1 academic spine center, and patients who present to our service may not be typical of the patients who present to a community hospital. The fact that our center comprises 2 hospitals (a tertiary care center and an affiliated community hospital) may help to ameliorate this potential limitation: approximately one third of our participants were enrolled from the affiliated community hospital.

Third, reliance on self-report for attendance to physical therapy may lead to a bias. Subgroups of the population may have been differentially affected by this bias, leading to spurious associations between these factors and self-reported attendance in physical therapy. Self-report bias may be mitigated by the inclusion of the physical-therapist-rated engagement in physical therapy. That our findings were similar for both measures lends confidence in the self-report attendance in physical therapy.

A final limitation may be the conceptual model (Figure 1), which draws relationships among patient characteristics, patient activation, and health behavior. Although we were able to begin to estimate the association between the psychological factors and patient activation and the combined association of these factors with adherence to physical therapy, our inferences were limited. Because of our small sample size, we were unable to perform structural equation modeling to test the strength and direction of these relationships. Inability to discern causal pathways underlines the need to study this model in a larger setting.

We have shown the relationship between patient activation and adherence with physical therapy. The additional information provided by patient activation in predicting adherence to physical therapy highlights the importance of psychological factors and personal competencies in understanding health behavior. The literature has previously supported this conclusion, but the use of a simple scale to measure the influence of these many factors on health behavior is a novel contribution. The PAM is an instrument with great potential to be incorporated into clinical practice. With the PAM, a healthcare provider may be able to quickly assess an individual’s propensity to engage in adaptive health behavior. Future research will address if preoperative intervention can increase patient activation and lead to increased adoption of positive health behaviors and improved functional recovery.

Key Points.

Patient activation varies among individuals, especially across race and income groups.

Patient activation is negatively associated with the presence of depressive symptoms and positively associated with self-efficacy and hope.

Patient activation provides significant additional information with which to predict adherence to physical therapy

Acknowledgments

Federal funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

This project was supported by grant number 1 R03 HS016106 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

References

- 1.North American Spine Society Task Force on Clinical Guidelines. Phase III Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care Specialists. Spondylosis, Lytic Spondylolisthesis, and Degenerative Spondyloslisthesis (SLD), La-Grange, IL: North American Spine Society; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verbunt JA, Seelen HA, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Fear of injury and physical deconditioning in patients with chronic low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:1227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greiner-Perth R, Bohm H, Allam Y. A new technique for the treatment of lumbar far lateral disc herniation: technical note and preliminary results. Eur Spine J 2003;12:320–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce J, Kuperstein J. Improving physical therapy referrals. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:1183–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geelen RJGM Soons PHGM. Rehabilitation: an ‘everyday’ motivation model. Patient Educ Couns 1996;28:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1005–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, et al. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1097–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rovner BW, Folstein MF. Mini-mental state exam in clinical practice. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1987;22:99, 103,, 106,, 110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichholz KM, Ryken TC. Complications of revision spinal surgery. Neurosurg Focus 2003;15:E1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45: 613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connell RL, Lim LLY. Utility of the Charlson comorbidity index computed from routinely collected hospital discharge diagnosis codes. Methods Inf Med 2000;39:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kortte KB, Falk LD, Castillo RC, et al. The Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale: development and psychometric properties. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:877–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, et al. Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? J Ambul Care Manage 2007;30:21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res 2005;40: 1918–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Optimism In: Synder CR, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005:231–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994;67:1063–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol 1985;4: 219–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Owens JF, et al. Dispositional optimism and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery: the beneficial effects on physical and psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;57:1024–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babyak MA, Snyder CR, Yoshinobu L. Psychometric properties of the Hope Scale: a confirmatory factor analysis. J Res Pers 1993;27:154–69. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, et al. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colon RM, Wiatrek DE, Evans RI. The relationship between psychosocial factors and condom use among African-American adolescents. Adolescence 2000;35:559–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontaine KR, Cheskin LJ. Self-efficacy, attendance, and weight loss in obesity treatment. Addict Behav 1997;22:567–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fortenberry JD, Brizendine EJ, Katz BP, et al. The role of self-efficacy and relationship quality in partner notification by adolescents with sexually transmitted infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:1133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JA. Self-efficacy theory as a framework for community pharmacy-based diabetes education programs. Diabetes Educ 1996;22:237–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sitharthan T, Kavanagh DJ. Role of self-efficacy in predicting outcomes from a programme for controlled drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend 1990;27: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strecher VJ, DeVellis BM, Becker MH, et al. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ Q 1986;13:73–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zebracki K, Drotar D. Outcome expectancy and self-efficacy in adolescent asthma self-management. Child Health Care 2004;33:133–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr 1978; 6:160–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tukey JW. The philosophy of multiple comparisons. Stat Sci 1991;6: 100–16. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisberg S Applied Linear Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellino T, Tluczek A, Collins M, et al. Increasing self-efficacy through empowerment: preoperative education for orthopaedic patients. Orthop Nurs 1998;17:48–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Quear T, et al. Significance of poor patient participation in physical and occupational therapy for functional outcome and length of stay. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:1599–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]