Abstract

Background:

The advent of Remicade® biosimilars, Remsima®, Inflectra® and, more recently, Flixabi®, has brought along the potential to decrease the costs associated with this therapy, therefore increasing its access to a larger group of patients. However, and in order to assure a soft transition, one must make sure the assays and algorithms previously developed and optimized for Remicade perform equally well with its biosimilars. This study aimed to: (a) validate the utilization of Remicade-optimized therapeutic drug monitoring assays for the quantification of Flixabi; and (b) determine the existence of Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi cross-immunogenicity.

Methods:

Healthy donors’ sera spiked with Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi were quantified using three different Remicade-quantification assays, and the reactivity of anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima sera to Remicade and to its biosimilars was assessed.

Results:

The results show that all tested Remicade-infliximab-optimized assays measure Flixabi as accurately as they measure Remicade and Remsima: the intraclass correlation coefficients between theoretical and measured concentrations varied from 0.920 to 0.990. Moreover, the interassay agreement values for the same compounds were high (intraclass correlation coefficients varied from 0.936 to 0.995). Finally, the anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima sera reacted to the different drugs in a similar fashion.

Conclusions:

The tested assays can be used to monitor Flixabi levels. Moreover, Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi were shown to have a high cross-immunogenicity, which supports their high similarity but prevents their switching in nonresponders with antidrug antibodies.

Keywords: biosimilars, Flixabi®, Remicade®, therapeutic drug monitoring

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are a group of immunity-driven conditions characterized by the presence of flares intertwined with remission periods. These conditions include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), and are thought to arise from a complex interplay involving environmental and immunological factors on a susceptible genetic background. Tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) is a key cytokine that plays a major role in IBD pathophysiology.1 The development of anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies has therefore revolutionized the therapeutic approach and natural progression of IBD: the utilization of these biological therapies led to decreased rates of steroid utilization, surgery and hospitalization, increased rates of clinical remission and mucosal healing, and an overall improvement in the health-related quality of life of IBD patients.2–4 Four different anti-TNFα agents are currently being used for the treatment of IBD, of which infliximab (name brand Remicade®, Remicade is manufactured by Merck Sharp and Dohme, Ireland) was the first to be approved (Remicade will be used throughout this article when referring to the original infliximab drug). Remicade is a chimeric monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) anti-TNFα antibody composed of a murine variable region (25%) and a constant human region (75%). Its multiple mechanisms of action include the reduction of lymphocyte and leucocyte migration to sites of inflammation, the downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the induction of TNFα-producing cell apoptosis, among others.4

Notwithstanding their pivotal role in the treatment of IBD and other autoimmune diseases, biologic therapies are substantially expensive. In fact, they are currently the main drivers of cost in IBD units.5 For that reason, biosimilars are an attractive alternative: these molecules are highly similar (though not identical) to their reference products in structural, functional, biological and clinical terms. With an expedited regulatory process, biosimilars have the potential to reduce the cost of biological therapies by 25–40%, hence increasing their availability.5 Despite some controversy linked to the regulatory process, mostly concerning the extrapolation of clinical indications,6 two Remicade biosimilars have been approved both in Europe and in the USA.

Remsima® (Celltrion, Incheon, South Korea) and Inflectra® (Hospira, Illinois, USA) are the brand names of CT-P13, the first Remicade biosimilar approved by the European Medicine Agency (EMA) in September 2013 and by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2016. Flixabi® (Samsung Bioepsis, South Korea) is the brand name of SB2, which was the second Remicade biosimilar that received marketing authorization from the EMA (in May 2016) and from the FDA (in April 2017). Given the biosimilar expedited regulatory process, Remsima, Inflectra and Flixabi were approved for all the therapeutic indications of their originator drug, including CD and UC. Remsima is the only Remicade biosimilar for which real-world observational data concerning IBD therapy are already available: so far, these studies are promising, as they show no significant differences between Remsima and Remicade in what concerns efficacy, safety and immunogenicity.7,8

There have been several attempts to optimize Remicade therapy in IBD patients. It is now commonly accepted that the rates of response and remission increase when a drug concentration-guided individualized therapy is followed.3,9,10 Given their overall similarity to Remicade®, one can rationally expect that this pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship also occurs with the biosimilars Remsima and Flixabi.11 The process of adjusting the drug dosage and the infusions’ interval in order to achieve a particular therapeutic window, within which the drug has its maximum efficacy with the minimum associated toxicity, is dependent on an accurate and systematic assessment of drug levels, named therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Multiple systems, mostly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based, have been developed and are now available to monitor patients’ Remicade levels throughout time. However, to safely employ TDM to tailor treatment in Flixabi- and Remsima-treated patients, one must determine whereas the systems developed and optimized to quantify Remicade are equally accurate in the quantification of its biosimilars.

Our group has previously demonstrated that a number of Remicade quantification methods can be safely applied to quantify Remsima.12 This study was meant to extend those analyses in order to include the recently-approved Flixabi. Shortly, our aim was to assess the efficacy, accuracy and interassay agreement of three Remicade quantification assays in the monitoring of Flixabi levels. Additionally, we have also tested the cross-reactivity of antidrug antibodies (ADAs) anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima with Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi.

Material and methods

Spiked samples and quantification assays

Spiked samples of known Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi concentrations were generated by diluting the appropriate amount of each drug (Remicade, Remsima, Flixabi) into a pool of sera extracted from control donors. Each spiked concentration was repeated between six and nine times and analysed in duplicate. Samples were then quantified using one in-house assay and two commercially available kits: the Quantum Blue® infliximab: quantitative lateral flow assay (Buhlmann, Schönenbuch, Switzerland), hereafter referred to as Buhlmann; and the RIDASCREEN® IFX monitoring (R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany), hereafter referred to as R-Biopharm.

The in-house method was an ELISA assay commonly used in our laboratory and was carried out as previously described by Ben-Horin and colleagues.13–18 Briefly, serum samples were diluted and added to a plate precoated with TNFα (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). After 60 min of incubation and an appropriate number of washes, a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labelled goat antihuman fragment-crystallizable fragment antibody (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) was added and the plate was incubated for 60 min. Afterwards, tetramethylbenzidine (Millipore, MA, USA) substrate was added, and the reaction was stopped 3 min later with 2 mol/l H2SO4. Finally, the samples’ absorbance was read at 450/540 nm, and the Remicade was quantified by interpolating the absorbance values in a standard curve built with known concentrations of exogenous Remicade. The upper limit of quantification was calculated as the highest concentration of the standard curve multiplied by the sample dilution factor used.

Concerning the Buhlmann assay, a chip card containing the test information and calibration curve for each specific cartridge lot was supplied with each test kit. Briefly, serum samples were diluted 1:20 and an 80 µl aliquot was loaded into the port of the test cartridge. After a 15 min reaction, the cartridge was read and the results were shown on the point-of-care Buhlmann reader display. The lower and upper limits of quantification were 0.4 and 20 µg/ml, respectively.

Concerning the R-Biopharm method, the samples were diluted and added to the assay plate. After 60 min of incubation at 37°C and several washes, a conjugate was added to the plate and incubated for 30 min at the same temperature. Afterwards, the substrate was added and the reaction was interrupted 10 min later by adding the stop reagent. The sample absorbance was read at 450/620 nm. The manufacturer provided no information on the limits of quantification.

Whenever the results obtained were below or above the limits of quantification indicated for the in-house and Buhlmann methods, they were rounded to match those limits.

Antidrug antibodies’ cross-reactivity

Serum samples from IBD patients being treated with Remicade or Remsima were extracted immediately before an infusion. The presence of ADAs was determined routinely in these patients, and 74 serum samples were included in the study. Only samples positive for anti-Remicade or anti-Remsima antibodies were used. The presence of cross-reactivity between Remicade and its biosimilars was determined using an in-house procedure previously described by Ben-Horin and colleagues.13–18 Briefly, Remicade, Remsima or Flixabi were added to a plate precoated with TNFα. Afterwards, a diluted sample of serum (anti-Remicade or anti-Remsima) was added to the plate and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Goat antihuman lambda chain HRP-labelled antibody (Serotec, Oxford, UK) was then added, followed by another room temperature 60 min-incubation. Finally, TMB (3,3’,5,5’-tetramethybenzidine, Merckmillipore, USA) was added and allowed to react for 6 min, after which the reaction was stopped with H2SO4. Absorbances were read at 450/540 nm, and the results were obtained upon interpolation in a standard curve of goat antihuman F(ab’)2 fragment antibody (MP Biomedicals) and expressed as µg/ml-equivalent (for the purpose of brevity, the results are hereafter expressed as µg/ml). The lower limit of quantification was 1.2 µg/ml.

This study was approved by the ethics committees of all hospitals involved and by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority. All patients and control donors enrolled have signed an informed written consent giving permission for blood sample collection for medical research.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described using median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum values. The association between theoretical/measured concentrations, methods and the antidrug reactivity of Remicade and its biosimilars was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Moreover, Bland and Altman plots were used to compare the different techniques. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY, USA), whereas graphs were designed using Prism 7®.

Results

Drug quantification assays

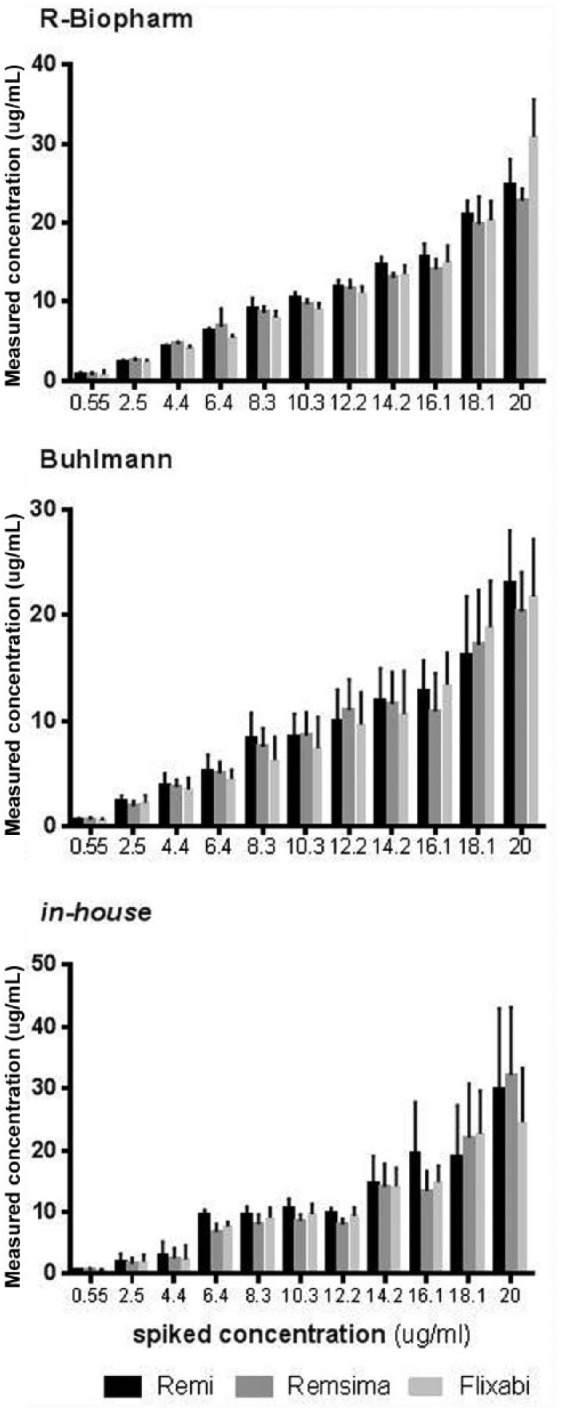

The spiked samples of Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi were quantified using the three assays referred to in the material and methods section (Figure 1). The results show that these assays measure similar amounts of each compound at any given concentration, with the standard deviations (SDs) being larger for the Buhlmann method. Accordingly, the mean intra-assay coefficient of variation was 6.4%, 3.4% and 11.7% for the in-house, R-Biopharm and Buhlmann assays, respectively. The average recovery rates of each drug were higher with the R-Biopharm assay (105%, 102%, and 105% for Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi, respectively) when compared with the Buhlmann (91%, 87%, and 86%, respectively) and the in-house methods (105%, 97%, and 99%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi-spiked samples measured by R-Biopharm, Buhlmann and the in-house assays.

Buhlmann, Quantum Blue® infliximab: quantitative lateral flow assay; R-Biopharm, RIDASCREEN® IFX monitoring.

Table 1 shows the intraclass ICCs and the average differences between the theoretical and the measured concentrations obtained using the different methods. The most accurate assay to quantify Remicade and Remsima is the R-Biopharm (with ICCs of 0.986 and 0.990, respectively), whereas the most accurate method to quantify Flixabi is the Buhlmann (with an ICC of 0.983). Still, all ICCs are rather high (above 0.920) and therefore all methods seem to accurately measure the different drugs. The R-Biopharm and the in-house methods have a negative average difference between theoretical and measured concentrations, which means that both methods tend to overestimate the drugs’ concentrations, whereas the opposite is observed for Buhlmann. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the average difference in Remsima and Flixabi quantified with Buhlmann is positive and excludes 0, which means that, in these cases, the underestimation is consistently observed throughout the entire range of tested concentrations.

Table 1.

Intraclass correlation coefficient between the theoretical and measured concentrations.

| ICC |

Difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | CI 95% | Average | CI 95% | ||

| R-Biopharm | |||||

| Spiked concentrations: Remicade | 0.986 | 0.949–0.996 | −0.72 | −1.82 | 0.38 |

| Spiked concentrations: Remsima | 0.990 | 0.964–0.997 | −0.10 | −0.98 | 0.77 |

| Spiked concentrations: Flixabi | 0.945 | 0.796–0.985 | −0.69 | −3.05 | 1.68 |

| Buhlmann | |||||

| Spiked concentrations: Remicade | 0.982 | 0.932–0.995 | 0.94 | −0.23 | 2.11 |

| Spiked concentrations: Remsima | 0.985 | 0.945–0.996 | 1.33 | 0.31 | 2.35 |

| Spiked concentrations: Flixabi | 0.983 | 0.938–0.996 | 1.28 | 0.14 | 2.41 |

| In house | |||||

| Spiked concentrations: Remicade | 0.951 | 0.818–0.987 | −1.31 | −3.54 | 0.92 |

| Spiked concentrations: Remsima | 0.920 | 0.702–0.978 | −0.46 | −3.42 | 2.50 |

| Spiked concentrations: Flixabi | 0.972 | 0.896–0.992 | −0.39 | −1.99 | 1.22 |

Buhlmann, Quantum Blue® infliximab: quantitative lateral flow assay; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; R-Biopharm, RIDASCREEN® IFX monitoring.

The ICCs between the different assays are shown in Table 2. Values tend to be high (the minimum is 0.936), which means that similar concentrations are obtained for each compound using different assays. R-Biopharm is particularly close to Buhlmann in what comes to Remicade and Remsima, whereas Buhlmann is particularly close to the in-house method in what comes to Flixabi. Overall, the Buhlmann assay yields values consistently lower than those obtained with R-Biopharm for all three drugs; on the other hand, the in-house method yields values consistently higher than those obtained with Buhlmann in what concerns Remicade and Flixabi. Moreover, the Bland–Altman plots suggest that the differences between the methods increase for higher concentrations but rarely exceed the ±1.96 SD interval (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 2.

Intraclass correlation coefficient between the different methods.

| ICC |

Difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | CI 95% | Average | CI 95% | ||

| Remicade | |||||

| R-Biopharm–Buhlmann | 0.990 | 0.961–0.997 | 1.66 | 0.70 | 2.63 |

| R-Biopharm–in house | 0.978 | 0.918–0.994 | −0.59 | −2.20 | 1.02 |

| Buhlmann–in house | 0.968 | 0.881–0.991 | −2.25 | −4.08 | −0.43 |

| Remsima | |||||

| R-Biopharm–Buhlmann | 0.995 | 0.980–0.999 | 1.44 | 0.79 | 2.08 |

| R-Biopharm–in house | 0.957 | 0.839–0.988 | −0.35 | −2.61 | 1.90 |

| Buhlmann–in house | 0.936 | 0.761–0.983 | −1.79 | −4.42 | 0.84 |

| Flixabi | |||||

| R-Biopharm–Buhlmann | 0.974 | 0.905–0.993 | 1.96 | 0.29 | 3.63 |

| R-Biopharm–in house | 0.979 | 0.922–0.994 | 0.30 | −1.32 | 1.92 |

| Buhlmann–in house | 0.986 | 0.946–0.996 | −1.66 | −2.85 | −0.48 |

Buhlmann, Quantum Blue® infliximab: quantitative lateral flow assay; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; R-Biopharm, RIDASCREEN® IFX monitoring.

Cross-immunogenicity

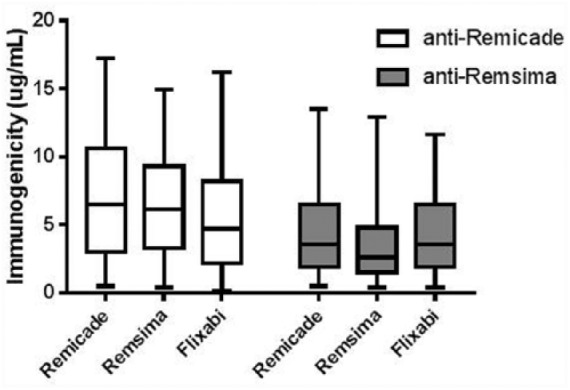

In order to determine the presence of cross-immunogenicity, the three drugs were tested with anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima sera extracted from IBD patients (Figure 2). The results show that the amount of antisera that reacted to Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi was similar (p = 0.293 for the anti-Remicade, and p = 0.538 for the anti-Remsima). In fact, the ICCs between the different drugs’ reaction to anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima sera were close to 1.0 (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Reactivity of Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi to anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima sera.

Table 3.

Intraclass correlation coefficient between the antidrug reactivity of Remicade and its biosimilars.

| ICC |

Difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | CI 95% | Average | CI 95% | ||

| Anti-Remicade serum | |||||

| Flixabi–Remsima | 0.988 | 0.977–0.994 | −0.83 | −1.13 | −0.53 |

| Flixabi–Remicade | 0.992 | 0.984–0.996 | −1.49 | −1.77 | −1.22 |

| Remicade–Remsima | 0.986 | 0.972–0.993 | 0.66 | 0.31 | 1.01 |

| Anti-Remsima serum | |||||

| Flixabi–Remsima | 0.989 | 0.978–0.994 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.52 |

| Flixabi–Remicade | 0.987 | 0.975–0.993 | −0.36 | −0.61 | −0.11 |

| Remicade–Remsima | 0.993 | 0.986–0.996 | 0.65 | 0.46 | 0.84 |

CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

Discussion

TDM is increasingly considered as a key step to optimize anti-TNFα treatment in IBD patients. Therefore, the advent of Remicade biosimilars carries along the necessity of validating the utilization of Remicade-quantifying assays, which were optimized for Remicade, with these somehow modified compounds. This study addressed the performance of three different Remicade-optimized quantification procedures, already validated to be used with Remsima, in the assessment of Flixabi concentrations. Moreover, we have addressed the presence of cross-immunogenicity between Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi. The Buhlmann assay tested in this study is particularly suitable for a clinical environment as the results are available within 15 min of placing the sample into the cartridge test, which allows an immediate adjustment of the drug dosage. In fact, when a traditional ELISA method is used, the dosage adjustment (if needed) is usually postponed to the next infusion, as the results take approximately 8 h.

The three assays used, R-Biopharm, Buhlmann and the in-house method, seem to be almost equally accurate in what concerns the quantification of Remicade and of its biosimilars. In fact, R-Biopharm and Buhlmann are slightly more accurate when measuring Remsima than when measuring its originator Remicade; as for the in-house method, measured values are closer to the theoretical concentrations in the case of Flixabi. Moreover, the values obtained when measuring each drug with the different quantification assays are rather similar, and the differences encountered tend to be larger when the drugs’ concentrations are above the critical values considered to be in the therapeutic window, and therefore should have no effect in the clinical practice.3,17,19 Overall, Buhlmann slightly underestimates Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi when compared with R-Biopharm, whereas the in-house method slightly overestimates Remi-cade and Flixabi when compared with Buhlmann. These results consolidate what has been previously published in the literature concerning Remsima, that is, Remicade-optimized methods perform equally well when measuring biosimilars’ levels.12,20–22 One can see only slight differences that are mostly likely the result of the small modifications in the biosimilars’ structure, which can be attributed to dissimilarities in the compounds’ biological synthesis (different cell lines or growth media, for instance), storage and transport.8,23,24

Immunogenicity is a key issue in Remicade and other anti-TNFα therapies: the formation of ADAs may directly or indirectly lower or even prevent the drug’s action.3 Cross-immunogenicity, that is, the abitility of ADAs to react against compounds other than the one that stimulated their appearance, is of utmost important from a clinical point of view. In fact, when an anti-TNFα therapy fails due to the presence of ADAs, one must consider the absence of cross-immunogenicity as a criterion for choosing a second anti-TNFα agent. Our results reveal that Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi react to a similar extent to anti-Remicade and anti-Remsima sera. These results come in line with what has been previously published regarding the cross-immunogenicity of Remsima and its originator.6,22,25

This study has a couple of limitations that we hereafter acknowledge: the results are based on in vitro-spiked samples only (no clinical samples were used); the in vitro samples were obtained spiking healthy donor sera (instead of sera extracted from IBD patients naïve to Remicade) and the cross-immunogenicity assays neither included an anti-Flixabi serum nor an anti-TNFα other than Remicade as a control serum.

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to demonstrate that Remicade-optimized quantification methods can be used to measure Flixabi levels, while consolidating the previously published results concerning Remsima in this context. In fact, our results suggest that either R-Biopharm, Buhlmann and the described in-house method can be used to measure Remicade biosimilars Remsima and Flixabi in an accurate fashion. Moreover, we have demonstrated the existence of cross-immunogenicity between Remicade, Remsima and Flixabi. This not only reinforces the similarity among these drugs, but also has some clinical implications: according to our results, a patient medicated with Remicade or Remsima whose therapy fails due to the presence of ADAs would not benefit from switching to Remicade, Remsima or Flixabi.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_1 for The performance of Remicade®-optimized quantification assays in the assessment of Flixabi® levels by F. Magro, C. Rocha, A. I. Vieira, H. T. Sousa, I. Rosa, S. Lopes, J. Carvalho, C. C. Dias and J. Afonso, in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Bühl-mann company for kindly providing the Buhlmann kit. Claudia Camila Dias would like to acknowledge the project NanoSTIMA(NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000016), which is financed by the North Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, and through the Euro-pean Regional Development Fund (ERDF). More-over, the authors would like to express their gratitude to Sandra Dias for her involvement as the GEDII coordinator and all the help during data collection, as well as to Catarina L Santos for scientific writing assistance.

Guarantor of the article: Fernando Magro.

FM: Study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; study supervision; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. JA and CR: quantification and cross-immunogenicity assays; analysis and interpretation of data. CCD: statistical analysis. All the other authors: recruitment of patients and collection of samples.

Drafting of the manuscript has been done by J. Afonso. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Portuguese IBD Group (GEDII, Grupo de Estudo da Doença Inflamatória Intestinal).

Conflict of interest statement: FM served as speaker and received honoraria from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Vifor, Falk, Laboratorios Vitoria, Ferring, Hospira and Biogen. IR served as a speaker/consultant for Merck Sharp and Dohme, Abbvie, Falk, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen and Takeda.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

F. Magro, Department of Biomedicine, Pharmacology and Therapeutics Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Alameda Prof. Hernâni Monteiro, 420-319 Porto, Portugal; Gastroenterology Department, Centro Hospitalar São João, Porto, Portugal; MedInUP, Centre for Drug Discovery and Innovative Medicines, Porto, Portugal.

C. Rocha, Department of Biomedicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal.

A. I. Vieira, Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada, Portugal

H. T. Sousa, Gastroenterology Department, Centro Hospitalar do Algarve, Portimão, Portugal Biomedical Sciences and Medicine Department, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal; Algarve Biomedical Centre, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal.

I. Rosa, Gastroenterology Department, Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

S. Lopes, Gastroenterology Department, Centro Hospitalar São João, Porto, Portugal

J. Carvalho, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Centro Hospitalar de Gaia, Gaia, Portugal

C. C. Dias, Health Information and Decision Sciences Department, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal Centre for Health Technology and Services Research, Porto, Portugal.

J. Afonso, Department of Biomedicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal Centre for Drug Discovery and Innovative Medicines, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal; MedInUP, Centre for Drug Discovery an Innovative Medicines, Porto, Portugal.

References

- 1. Levin AD, Wildenberg ME, Van den Brink GR. Mechanism of action of anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016; 10(8): 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn’s disease: results from a single-centre cohort. Gut 2009; 58(4): 492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gecse KB, Végh Z, Lakatos PL. Optimizing biological therapy in Crohn’s disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 10: 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klotz U, Teml A, Schwab M. Clinical pharmacokinetics and use of infliximab. Clin Pharmacokinet 2007; 46(8): 645–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gomollón F. Biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2015; 31(4): 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ben-Horin S, Heap GA, Ahmad T, et al. The immunogenicity of biosimilar infliximab: can we extrapolate the data across indications? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 9(Suppl. 1): 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Radin M, Sciascia S, Roccatello D, et al. Infliximab biosimilars in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. BioDrugs 2016; 31(1): 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Danese S, Bonovas S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Biosimilars in IBD: from theory to practice. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 14(1): 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vande Casteele N, Feagan BG, Gils A, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease: current state and future perspectives. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16(4): 378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Strik AS, Bots SJA, D’Haens G, et al. Optimization of anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2016; 9: 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gonczi L, Vegh Z, Golovics PA, et al. Prediction of short- and medium-term efficacy of biosimilar infliximab therapy. Do trough levels and antidrug antibody levels or clinical and biochemical markers play the more important role? J Crohns Colitis 2016; 11(6): 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Afonso J, De Sousa HT, Rosa I, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of CT-P13: a comparison of four different immunoassays. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2017; 10(9): 661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Afonso J, Lopes S, Gonçalves R, et al. Proactive therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab: a comparative study of a new point-of-care quantitative test with two established ELISA assays. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 44(7): 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Afonso J, Lopes S, Gonçalves R, et al. Detection of anti-infliximab antibodies is impacted by antibody titer, infliximab level and IgG4 antibodies: a systematic comparison of three different assays. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016; 9(6): 781–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Katz L, et al. The immunogenic part of infliximab is the F(ab’)2, but measuring antibodies to the intact infliximab molecule is more clinically useful. Gut 2011; 60(1): 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, et al. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13(3): 522–530e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, et al. Optimizing anti-TNF-α therapy: serum levels of infliximab and adalimumab are associated with mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14(4): 550–557.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ungar B, Anafy A, Yanai H, et al. Significance of low level infliximab in the absence of anti-infliximab antibodies. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(6): 1907–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silva-Ferreira F, Afonso J, Pinto-Lopes P, et al. A systematic review on infliximab and adalimumab drug monitoring: levels, clinical outcomes and assays. Infammatory Bowel Dis 2016; 22(9): 2289–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malíckova K, Duricova D, Bortlík M, et al. Serum trough infliximab levels: a comparison of three different immunoassays for the monitoring of CT-P13 (infliximab) treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Biologicals 2016; 44(1): 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schulze K, Koppka N, Lutter F, et al. CT-P13 (Inflectra, Remsima) monitoring in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Biologicals 2016; 44(5): 463–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gils A, Van Stappen T, Dreesen E, et al. Harmonization of infliximab and anti-infliximab assays facilitates the comparison between originators and biosimilars in clinical samples. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016; 22(4): 969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papamichael K, Van Stappen T, Jairath V, et al. Review article: pharmacological aspects of anti-TNF biosimilars in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42(10): 1158–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McKeage K. A review of CT-P13: an infliximab biosimilar. BioDrugs 2014; 28(3): 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Benhar I, et al. Cross-immunogenicity: antibodies to infliximab in remicade-treated patients with IBD similarly recognise the biosimilar Remsima. Gut 2016; 65(7): 1132–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_Figure_1 for The performance of Remicade®-optimized quantification assays in the assessment of Flixabi® levels by F. Magro, C. Rocha, A. I. Vieira, H. T. Sousa, I. Rosa, S. Lopes, J. Carvalho, C. C. Dias and J. Afonso, in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology