Abstract

Introduction and objective:

Elevated C-reactive protein is usually a good indicator of rheumatoid arthritis (RA); however, there are limitations that compromise its specificity and therefore there is an urgent need to identify more reliable diagnostic biomarkers to detect early stages of RA. In addition, identifying the correct therapeutic biomarker for the treatment of RA using methotrexate (MTX) would greatly increase the benefits experienced by the patients.

Materials and methods:

Primary normal synoviocytes human fibroblast-like synoviocytes (HFLS) and its phenotype rheumatic HFLS-RA cells were chosen for this study. The HFLS-RA–untreated and MTX-treated cells were subjected to microarray analysis.

Results:

Microarray data identified 74 differentially expressed genes. These genes were mapped against an RA inflammatory pathway, shortlisting 10 candidate genes. Gene expression profiling of the 10 genes were studied. Fold change (FC) was calculated to determine the differential expression of the samples.

Discussion:

The transcription profiles of the 10 candidate genes were highly induced in HFLS-RA cells compared with HFLS cells. However, on treating the HFLS-RA cells with MTX, the transcription profiles of these genes were highly downregulated. The most significant expression FC difference between HFLS and HFLS-RA (treated and untreated) was observed with HSPA6, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10 genes.

Conclusions:

The data from this study suggest the use of HSPA6, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10 gene expression profiles as potential diagnostic biomarkers. In addition, these gene profiles can help in predicting the therapeutic efficacy of MTX.

Keywords: CRP, RA, microarray, qRT-PCR, RA diagnostic and predictive biomarkers

Introduction

Measuring the C-reactive protein (CRP) as the main diagnostic biomarker for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is insufficient in predicting the disease. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify reliable diagnostic/predictive biomarkers in conjunction with CRP.

Rheumatoid arthritis a complex autoimmune disorder that can suddenly manifest with inflammation of joints. However, this is not always the case because many people have symptoms that may be transient before becoming permanent (nhs.uk/RA). This situation can be a diagnostic challenge for the general practitioners because very often laboratory tests (autoantibody assays) can appear to be normal in the early stages of the disease. The autoantibody assay monitors the level of antibodies such as CRP, rheumatoid factor, and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide. However, recent studies focused on the presence of citrullinated proteins during inflammation which is not necessarily specific to RA. Citrullination occurs in a wide range of inflammatory tissues, suggesting that this process is inflammation dependent rather than disease dependent.1 Thus, other diagnostic biomarkers may help in the early diagnosis of the disease.

Once diagnosis is confirmed, methotrexate (MTX) is the most preferred drug of choice compared with other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (nras.org.uk/MTX).2 Clinical diagnosis together with lab tests (eg, CRP) to monitor disease activities is used to determine optimal doses of MTX.2 The CRP measurements play a key role in the management and prognosis of RA because patients with persistently high levels of CRP are at high risk of bone degradation and require intense treatment strategies. More acceptable levels of CRP offer physicians an indication of the therapeutic efficacy of the medication. Although CRP is used as a diagnostic and predictive biomarker, this test has limitations as approximately 40% patients with RA are reported to have normal levels of CRP and elevated levels have been found in conditions other than RA such as inflammatory bowel disease and tuberculosis.3 Due to limitations that exist in the diagnosis of RA during the early stages of the disease, identifying reliable diagnostic and predictive biomarkers can ensure an effective early diagnosis of the condition and a more reliable monitoring procedure of patient response to therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture conditions

Primary human fibroblast-like synoviocytes (HFLS) and HFLS-rheumatoid arthritis (HFLS-RA) were purchased from the Culture Collections, Public Health England (PHE, Salisbury, UK). The cells were cultured in Synoviocyte Growth Medium (Culture Collections, PHE) and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and filtered air. The cells were passaged at 70% to 80% confluency and restricted to 5 passages. The cells were cultured according to Class II biohazard conditions in compliance with the Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens (ACDP) and were reported to be free of all pathogens.

Cell viability

To determine the inhibitory concentrations (IC50), the cells were seeded at a density of 2000 cells/well in 96-well plates in triplicate for 24 hours and incubated for a further 48 hours at various concentrations of MTX. The 2 mM stock concentration of MTX (Tocris, Abingdon, UK) was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°C. Untreated cells and DMSO (0.08%)-treated cells were used as the controls. The IC50 of MTX was determined using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Southampton, UK) and Tecan GENios Pro (Tecan, Grödig, Austria).

CRP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The HFLS and HFLS-RA cell culture supernatants were used to determine the level of CRP present in the samples (untreated and treated) using the CRP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) per manufacturer’s instructions. FLUOstar OPTIMA (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) plate reader measured the optical density set at 450 nm and the CRP levels of the samples were extrapolated using standard curves of known protein concentrations.

Gene expression profiling microarray analysis (IMGM Laboratories, Germany)

Drug treatment for microarray analysis: HFLS-RA cells were seeded in 75 cm2 culture flasks for 24 hours prior to treatment. Cells were treated with IC50 concentrations of MTX. The untreated cells (control) and MTX-treated cells were harvested after 48 hours and stored in RNAprotect Cell Reagent (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) at −80°C.

Total RNA isolation, purity and integrity: Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (100 ng) was spiked with in vitro–synthesized polyadenylated transcripts (One-Color RNA Spike-In Mix, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The spiked total RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) and then converted into Cyanine-3–labelled cRNA (Low Input Quick-Amp Labelling Kit One-Color, Agilent Technologies).

Microarray Hybridization: The quality of labelled non-fragmented cRNA was analysed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer using RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (Agilent Technologies). Each Cyanin-3–labelled cRNA sample (600 ng) was fragmented, hybridized at 65°C for 17 hours, and separated using Agilent SurePrint G3 Human Gene Expression 8x60K v2 Microarrays (AMADID 039494) with one-color–based hybridization (Gene Expression Hybridization Kit, Agilent Technologies).

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

The software tool Feature Extraction 10.7.3.1, GeneSpring GX 12.6.1 (both Agilent Technologies), Microsoft Excel 2010, and IMGM internal tool marfin v1.9 were used for the bioinformatics data analysis. Similarities between different samples based on global RNA expression profiles were assessed in a pairwise manner using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Fold change (FC) was calculated to determine the differential expression of the samples.

Messenger RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

The messenger RNA (mRNA) isolation kit (Roche, West Sussex, UK) was used to extract approximately 1 pg/cell mRNA. The First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) was used to transcribe 100 ng of isolated DNA. Using the cDNA as the template for PCR, the expression profiles of 10 genes with and without treatment were evaluated using quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Primers were designed using NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) Primer-BLAST software. The primer sequences (TIB Molbiol, Berlin, Germany) and lengths of amplicons are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The right and left sequences, alongside annealing temperatures and amplicon size of the primers used for quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

| Genes | Primer sequences | Annealing temp (°C) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL14A1 | 5′AGACGAGGTGGTGGTAGATG3′ 5′AGCAGTGTGGGCATAGATTG3′ |

56 | 106 |

| CXCL12 | 5′GACAAGTGTGCATTGACCCG3′ 5′CTCATGGTTAAGGCCCCCTC3′ |

58 | 173 |

| CYTL1 | 5′AGATCACCCGCGACTTCAAC3′ 5′GTACAGCCTGGGCAGGTATC3′ |

58 | 77 |

| HSPA6 | 5′AATCTGTCGCCCCATCTTCTC3′ 5′GCCCATAGCATAGCCCTGAC3′ |

59 | 174 |

| IFITM1 | 5′CGCCAAGTGCCTGAACATC3′ 5′GTCACAGAGCCGAATACCAGT3′ |

57 | 87 |

| IL-6 | 5′GGTACATCCTCGACGGCATCT3′ 5′GTGCCTCTTTGCTGCTTTCAC3′ |

59 | 81 |

| IL-7 | 5′GTGACTATGGGCGGTGAGAG3′ 5′GCTACTGGCAACAGAACAAGG3′ |

59 | 141 |

| MMP1 | 5′AGTGACTGGGAAACCAGATGCTGA3′ 5′GCTTGACCCTCAGAGACCTT3′ |

62 | 162 |

| MMP13 | 5′CGCGTCATGCCAGCAAATTCCATT3′ 5′GTTCCAGCCACGCATAGTCA3′ |

64 | 323 |

| TNFSF10 | 5′TGGGCATTCATTCCTGAGCA3′ 5′GGTTGTGGCTGCTCTACTCA3′ |

63 | 525 |

GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used as a control. Primer (226 bp) sense: 5′gagtcaacggatttggtcgt, antisense: 5′ttgattttggagggatctcg. The PCR was performed using FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green 1 (Roche) in a LightCycler Real-Time PCR Detection System (Roche Diagnostics, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany) according to the protocol described previously.4

Quantitative amplification was monitored by the level of fluorescence reflecting the cycle number at the detection threshold (crossing point). Crossing points were used for quantification of the copy number of genomic DNA normalized using GAPDH as a reference gene. A standard curve was generated using the crossing points generated from different concentrations of genomic DNA with known copy numbers. Different crossing points for each gene were normalized using a standard curve to obtain the copy numbers for each of the amplified genes. All PCR reactions were performed in triplicate and a negative control (no DNA) was included.

Results

The MTX IC50 determination on HFLS-RA cells was performed following 48 hours incubation and cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo assay. The HFLS-RA cells treated with MTX induced apoptosis of 50% cell population at a concentration of 278.7 ± 2.0 μM.

To obtain comparative gene expression analysis of the effects of MTX on HFLS-RA cells, RNA microarray was performed. The gene expression profiling was performed on 2 sets of HFLS-RA cells (MTX treated and on untreated as a control) each consisting of 2 samples. The samples were analysed on Agilent SurePrint G3 Human Gene Expression 8x60K v2 Microarray. The data indicated a significant effect of the inhibitory compound on HFLS-RA. The differentially expressed RNAs for each of the treated groups were compared with the untreated cells (control). The microarrays were performed in duplication to ensure accurate statistical analysis. The differential RNA expressions were assessed for MTX vs control. To identify significantly differentially expressed genes in these pairwise comparisons, a filtering approach using P ≤ .05 and |FC| ≥ 2) was applied to the data which identified 74 genes differentially expressed (21 upregulated and 53 downregulated; Table 2).

Table 2.

The list of 74 genes identified to be differentially expressed in sampled treated with MTX.

| Gene | MTX FC | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ADAMTSL2 | Down | ADAMTS-like 2 (ADAMTSL2) |

| AKD1 | Up | Clone BRCAN2014229 |

| ANGPTL7 | Down | Angiopoietin-like 7 |

| ANKRD1 | Up | Ankyrin repeat domain 1 (cardiac muscle) |

| APLN | Down | Apelin (APLN) |

| ARHGAP32 | Down | Rho GTPase activating protein 32 (ARHGAP32) |

| BCAR4 | Down | Cancer anti-estrogen resistance 4 |

| CCDC81 | Up | Coiled-coil domain containing 81 |

| CCL5 | Down | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5) |

| CCRN4L | Up | CCR4 carbon catabolite repression 4-like |

| CD248 | Up | CD248 molecule, endosialin (CD248) |

| CD274 | Down | CD274 molecule (CD274) |

| CD300A | Up | CD300a molecule (CD300A) |

| CH25H | Down | Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (CH25H) |

| CHI3L2 | Down | Chitinase 3-like 2 (CHI3L2) |

| COL14A1 | Down | Collagen, type XIV, α1 (COL14A1) |

| CP | Down | Ceruloplasmin (ferroxidase) (CP) |

| CRHR2 | Down | Corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 2 (CRHR2) |

| CRTAC1 | Down | Cartilage acidic protein 1 (CRTAC1) |

| CRTAM | Down | Cytotoxic and regulatory T cell molecule (CRTAM) |

| CXCL12 | Down | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12) |

| CYTL1 | Down | Cytokine-like 1 (CYTL1) |

| DDIT4L | Down | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4-like (DDIT4L) |

| DIO2 | Down | Deiodinase, iodothyronine, type II (DIO2) |

| DIO3 | Down | Deiodinase, iodothyronine, type III (DIO3) |

| DNAH10 | Up | Dynein, axonemal, heavy chain 10 (DNAH10) |

| ERVK13-1 | Up | Endogenous retrovirus group K13, member 1 (ERVK13-1) |

| ERVMER34-1 | Down | Endogenous retrovirus group MER34, member 1 (ERVMER34-1) |

| FAM20A | Down | Family with sequence similarity 20, member A (FAM20A) |

| FGFBP2 | Down | Fibroblast growth factor binding protein 2 (FGFBP2) |

| FLJ45950 | Down | cDNA FLJ45950 fis, clone PLACE7008136. [AK127847] |

| GALNTL2 | Down | UDP-N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-like 2 (GALNTL2) |

| GJB2 | Down | Gap junction protein, β2, 26 kDa (GJB2), mRNA [NM_004004] |

| GPR88 | Down | Homo sapiens G protein–coupled receptor 88 (GPR88) |

| HEATR7B1 | Up | HEAT repeat containing 7B1 (HEATR7B1) |

| HK2 | Down | Hexokinase 2 (HK2) |

| HLF | Up | Hepatic leukaemia factor (HLF) |

| HSPA6 | Down | Heat shock 70kDa protein 6 (HSP70B′) (HSPA6) |

| IFITM1 | Down | Interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (9-27) (IFITM1) |

| IGFN1 | Up | Immunoglobulin-like and fibronectin type III domain containing 1 (IGFN1) |

| IL36A | Down | Interleukin 36, α (IL36A) |

| IL-6 | Down | Interleukin 6 (interferon, β2) (IL-6) |

| IL-7 | Down | Interleukin 7 (IL-7), transcript variant 1 |

| LAMTOR3 | Down | Late endosomal/lysosomal adaptor, MAPK and MTOR activator 3 (LAMTOR3) |

| LGALS8-AS1 | Down | LGALS8 antisense RNA 1 (non-protein coding) (LGALS8-AS1) |

| LOC649201 | Up | Paraneoplastic antigen like 6A-like (LOC649201) |

| MAFB | Down | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B (MAFB) |

| MCHR1 | Down | Melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 1 (MCHR1) |

| MIR17HG | Down | MiR-17-92 cluster host gene (non-protein coding) (MIR17HG) |

| MMP1 | Down | Matrix metallopeptidase 1 (interstitial collagenase) (MMP1) |

| MMP13 | Down | Matrix metallopeptidase 13 (collagenase 3) |

| MSMP | Down | Microseminoprotein, prostate associated (MSMP) |

| NHLH1 | Up | Nescient helix loop helix 1 (NHLH1) |

| NPPC | Down | Natriuretic peptide C (NPPC) |

| NR3C2 | Up | Nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 2 (NR3C2) |

| OTP | Down | Homeobox (OTP) |

| PARK2 | Down | Parkinson protein 2, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (Parkin) (PARK2) |

| RBM47 | Down | RNA binding motif protein 47 (RBM47) |

| RELT | Down | RELT tumour necrosis factor receptor (RELT) |

| RND1 | Down | Rho family GTPase 1 (RND1) |

| RPGR | Up | Retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) |

| SLC2A5 | Down | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose/fructose transporter), member 5 (SLC2A5) |

| SNORD103A | Up | Small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 103A (SNORD103A) |

| SPDYE3 | Up | Speedy homolog E3 (Xenopus laevis) (SPDYE3) |

| TCTEX1D1 | Up | Tctex1 domain containing 1 (TCTEX1D1) |

| TLR2 | Down | Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) |

| TMCO2 | Down | Transmembrane and coiled-coil domains 2 (TMCO2) |

| TNFSF10 | Down | Tumour necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 10 (TNFSF10) |

| TREM1 | Down | Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM1) |

| TRIML2 | Up | Tripartite motif family-like 2 (TRIML2) |

| TRPA1 | Down | Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A (TRPA1) |

| VAV3 | Down | vav 3 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (VAV3), variant 1 |

| WDR33 | Up | WD repeat domain 33 (WDR33), transcript variant 1 |

| WDR66 | Up | WD repeat domain 66 (WDR66), transcript variant 1 |

Abbreviations: FC, fold change; MTX, methotrexate.

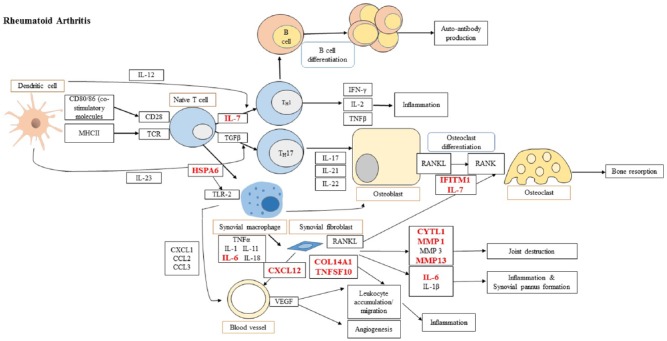

The 74 differentially expressed genes were mapped against RA inflammatory pathways shortlisting 10 genes. The adopted and modified RA pathway (KEGG ID: hsa05323) is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Candidate targets which are involved into rheumatoid arthritis pathway adopted and modified from KEGG ID: hsa05323) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?map=hsa05323&show_description=show).

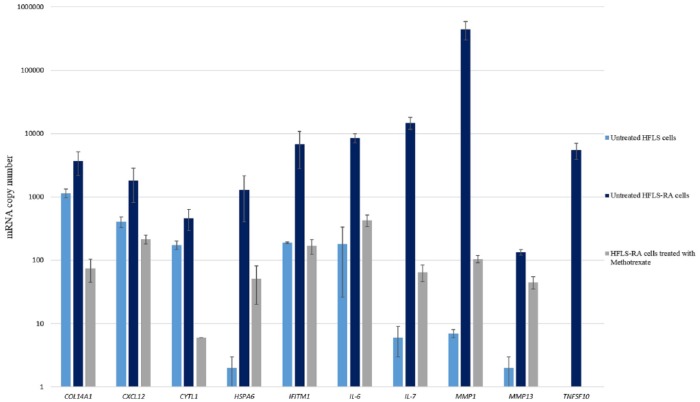

The 10 candidate genes were further analysed using qRT-PCR in HFLS-RA–treated and HFLS-RA–untreated cells. The qRT-PCR copy number analysis of the 10 candidate genes in untreated HFLS, untreated HFLS-RA, and MTX-treated HFLS-RA cells are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Figure 2.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction gene expression profile. Histogram showing the gene expression analysis for untreated HFLS, untreated HFLS-RA, and HFLS-RA treated with MTX IC50 concentrations (mean ± SD [n = 3]). HFLS indicates human fibroblast-like synoviocytes; mRNA, messenger RNA; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 3.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction copy number analysis of the candidate genes in untreated HFLS, untreated HFLS-RA, and MTX-treated HFLS-RA cells.

| Gene | Untreated HFLS cells | Untreated HFLS-RA cells | HFLS-RA cells treated with MTX |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL14A1 | 1145 ± 183 | 3676 ± 1498 | 75 ± 30 |

| CXCL12 | 407 ± 78 | 1820 ± 1011 | 216 ± 34 |

| CYTL1 | 175 ± 26 | 464 ± 172 | 6 ± 0 |

| HSPA6 | 2 ± 1 | 1287 ± 883 | 51 ± 31 |

| IFITM1 | 190 ± 6 | 6841 ± 4047 | 169 ± 45 |

| IL-6 | 181 ± 155 | 8504 ± 1403 | 428 ± 87 |

| IL-7 | 6 ± 3 | 14,840 ± 3214 | 65 ± 19 |

| MMP1 | 7 ± 1 | 444,768 ± 146,191 | 105 ± 14 |

| MMP13 | 2 ± 1 | 134 ± 13 | 45 ± 10 |

| TNFSF10 | 1 ± 0 | 5440 ± 1548 | 1 ± 0 |

Abbreviations: MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; HFLS, human fibroblast-like synoviocytes.

Values presented are mean ± SD, n = 3.

The CRP Human SimpleStep ELISA kit was used to determine the concentration of CRP present in the tissue culture supernatant of HFLS-RA cells for untreated and MTX-treated conditions. The unknown samples were quantified using a standard curve of known concentrations of CRP expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). The concentration of CRP quantified in the cell culture supernatant of HFLS, untreated HFLS-RA, and MTX-treated RA cells was 2.01 ± 0.77, 4.98 ± 1.06, and 1.31 ± 0.69, respectively.

Discussion

The primary HFLS and HFLS-RA cells are usually isolated from synovial tissue. These cells can be used as a good in vitro model for studying the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases, such as RA. The HFLS cells play a key role in RA progression due to their ability to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteases, whereas the rheumatoid HFLS-RA cells are involved in increasing invasiveness into the extracellular matrix accelerating joint destruction.5 Thus, HFLS and their phenotype HFLS-RA cells were chosen to identify potential biomarkers for RA using 10 microarray-shortlisted candidate genes (COL14A1, CXCL12, CYTL1, HSPA6, IFITM1, IL-6, IL-7, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10). These genes are involved directly or indirectly in the inflammatory pathway as shown in the literature and human GeneCards database (Table 4).

Table 4.

The shortlisted 10 candidate genes identified for this study.

| Gene | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| COL14A1 | COL14A1 codes for the α chain of type XIV collagen and is classified under the FACIT family. Increased accumulation of FACIT collagens has been implicated in the process of fibrosis which often occurs after injury or inflammation | Ansorge et al6 |

| CXCL12 | CXCL12 (stromal cell–derived factor 1) is an antimicrobial gene and codes for the ligand of the chemokine CXCR4 receptor. The role of this receptor/ligand complex has been highlighted in inflammation | Döring et al7 |

| CYTL1 | CYTL1 codes for a protein which is specifically present in bone marrow and cord blood cells that carry the CD34+ surface antigen. In vivo studies conducted have demonstrated that CYTL1 maintains cartilage homeostasis | Ai et al8 |

| HSPA6 | HSPA6 codes for the HSP70B′ protein which is not detected in most cells under normal conditions, however, is elevated under austere stress conditions and can also act in a cytoprotective manner depending on the cellular type and environment | Kuballa et al9 |

| IFITM1 | IFITM1 codes for a member of the IFN-induced transmembrane protein family. Studies have identified the role of this protein in the activation of IFN signalling pathways and its cell adhesion functions | Van Holten et al10 |

| IL-6 | IL-6 codes for a pleotropic cytokine which has a critical role in the pathophysiology of RA. It has been reported to be highly expressed in the synovium of patients with RA as it stimulates synovitis and joint destruction | Srirangan and Choy11 |

| IL-7 | IL-7 is involved in the proliferation and development of T cells along with differentiation of osteoclasts and RANKL production which leads to bone resorption | Churchman and Ponchel12 |

| MMP1 | MMP1 codes for a collagenase of the MMP family which has an important role in breaking down the ECM and has been implicated in processes such as tissue remodelling and RA | Green et al13 |

| MMP13 | MMP13 codes for a protease belonging to the M10 peptidase family of MMPs that is particularly involved in the cleavage of type II collagen which is a major constituent of joint cartilage | Jüngel et al14 |

| TNFSF10 | TNFSF10 codes for a cytokine belonging to the TNF family of proteins and selectively mediates apoptosis in malignant and abnormal cells, however, does not damage normal cells. | Morel and Audo16,17 |

Biomarkers for an early diagnosis of RA

A comparison was done using the 10 candidate gene expression profiles in HFLS vs HFLS-RA (both untreated). The qRT-PCR data demonstrated that HFLS-RA cells had significantly higher expression levels of these genes compared with the HFLS cells. The level of expression of COL14A1, CXCL12, and CYTL1 genes was found to be 3-, 4-, and 3-fold higher, respectively, in HFLS-RA cells compared with HFLS.

Previous studies using integrated analysis of microRNA (miRNA) and epigenetic control enabled the identification of novel dysregulated targets including COL14A1 and CXCL12 that are regulated by DNA methylation and are targeted by miRNAs with potential use as clinical markers for RA.17 Furthermore, an in vivo study indicated that CYTL1 is important for maintenance of cartilage homeostasis and Cytl1−/− mice exhibited joint destruction as a result of cartilage deterioration.8

There was a significantly higher expression (P < .001) of HSPA6 in HFLS-RA cells compared with normal synoviocytes. The higher expression of HSPA6 found in this study may be implicated in the survival of RA cells as previously suggested.18

Similarly, the expression of IFITM1 was significantly higher in HFLS-RA cells compared with normal HFLS. Previously, the role of this protein in the activation of IFN signalling pathways and its cell adhesion functions has been identified.10

There was a significant increase in the expression of IL-6 in HFLS-RA cells compared with normal HFLS. However, the difference was 47-fold and not as elevated as other candidate genes such as IL-7, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10. It was suggested that IL-6 promotes an acute phase response and promotes the synthesis of CRP, which is currently used in clinical diagnosis to provide a measure of systemic inflammation in RA.19

IL-7 is a cytokine which has been reported to be highly expressed in the synovium and synovial fluid of patients with RA and it has been suggested that blocking IL-7 could be of therapeutic value.12 This investigation found that the HFLS-RA cells possess a significantly higher expression of IL-7 (2.4 × 103-fold) compared with normal synoviocytes. It has been reported that IL-7 is highly expressed in various cell types including macrophages, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts and elevates the production of inflammatory cytokines.20

The expression of MMP1 has been reported to increase in the synovial fluid of patients with RA21 and this was observed in this study where the HFLS-RA cells were found to have a significantly higher expression of MMP1 compared with normal HFLS cells. MMP1 was upregulated 63.5 × 103-fold in RA cells. Researchers have also emphasized that the inflammatory activity observed in RA correlates with the level of MMP1 present in the synovial fluid.21 Therefore, MMP1 could act as a diagnostic biomarker for RA disease activity, hence a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Interestingly, there was a significantly higher expression of MMP13 in HFLS-RA cells when compared with normal HFLS cells (67-fold upregulation). MMP13-positive cells have been previously identified as being present in synovial joints mainly in pannus tissues of patients with RA.22,23

TNFSF10 not only induces apoptosis in a subsection of HFLS-RA cells but also contributes towards proliferation in the remaining cells via the p38 and ERK1/2 MAPK pathway.15 It has also been suggested that TNFSF10 has a defensive role in the early onset of RA; however, it has the effect of promoting disease activity.16,24-26 In this study, a significant upregulation (P < .001) of TNFSF10 was observed in HFLS-RA cells compared with the level in normal cells.

MTX therapeutic biomarkers for RA

Methotrexate is a first-line drug for the treatment of several rheumatic diseases. However, it is difficult to predict the response to this drug based on clinical manifestations; thus, there is the need for therapeutic biomarkers to monitor the efficacy of this drug.

The microarray data showed downregulation of the 10 candidate genes (COL14A1, CXCL12, CYTL1, HSPA6, IFITM1, IL-6, IL-7, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10). We evaluated these genes as therapeutic biomarkers by comparing their expression profile between untreated and MTX-treated HFLS-RA cells.

Methotrexate treatment of HFLS-RA cells downregulated the expression of COL14A1, CXCL12, and CYTL1 genes.

The treatment of HFLS-RA cells with MTX was found to decrease the expression of IFITM1 by 40-fold, thus decreasing the expression of the gene to levels observed in normal HFLS cells. Methotrexate has the ability to act as an IFN-γ inhibitor and suppresses the expression of IFN-induced MHC-II genes. The expression of MHC-II has been previously shown to be associated with a susceptibility to RA,27 therefore inhibiting the expression of these genes is a viable therapeutic strategy for the treatment of RA.

Methotrexate was found to downregulate the expression of IL-7 228-fold compared with the untreated condition. Previously, it was reported that a decrease in the serum level of IL-7 was reported from patients with RA that had undergone MTX therapy for a prolonged period of time (over 3 months).28

Methotrexate was also found to decrease the expression of MMP1 by 4.2 × 103-fold. Therefore, treatment of RA with MTX is an effective strategy for suppressing the production of MMP1 which can result in a marked reduction of joint destruction.

On treatment of HFLS-RA cells with MTX, the expression of MMP13 was downregulated 3-fold. The patients with RA who had undergone MTX treatment for a period of 6 months exhibited a significant decrease in serum concentration of MMP13 which also decreased RA disease activity such as inflamed and painful joints.29 Therefore, in addition to MMP1, MMP13 can be a potential therapeutic target for RA to aid the treatment of the condition. The precise mechanism by which MTX treatment inhibits the expression of MMP13 needs to be further investigated.30

It was found that MTX was able to decrease the gene expression level of TNFSF10 by 5440-fold. Methotrexate also decreased the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 as a result of an elevation in the level of extracellular adenosine, which can subsequently decrease the expression of TNFSF10 as the inflammatory environment required for the production of this cytokine is compromised. This finding would suggest that TNFSF10 could be an effective diagnostic and predictive biomarker for RA.

C-reactive protein

There was a significant difference (P < .05) in the concentration of CRP present in the supernatant of HFLS-RA cells compared with the normal synoviocytes. The concentration of CRP in the untreated HFLS-RA sample was 4.98 pg/mL compared with 2.01 pg/mL in HFLS cells and 1.31 pg/mL in MTX-treated HFLS-RA cells.

Methotrexate can lower the expression level of IL-6, IL-7, HSPA6, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10 and subsequently CRP, which can lead to the suppression of various inflammatory events including the decrease in the activation and differentiation of T and B lymphocytes, autoantibody production, and osteoclast differentiation which in turn decreases RA-related bone degradation and systemic inflammation.

In this study, we did not measure the CRP transcripts in the cultured cells. The initial microarray data (Table 2) did not list CRP as a gene that is differentially expressed on treatment with MTX. The CRP serum concentration may not correlate with the level of mRNA due to an important posttranscriptional mechanism that modulates the expression of the inflammatory marker CRP.31 However, the measurements of CRP mRNA expression could provide important information that may be an improvement on the measurement of the CRP protein levels.

Conclusions

One of the key aims of this work was to identify reliable diagnostic/predictive biomarkers for RA. Although all the shortlisted candidate gene transcription profiles were upregulated in HFLS-RA when compared with the normal HFLS cells, they were downregulated due to the MTX treatment. The highest FC difference between normal synoviocytes and HFLS-RA cells was observed in HSPA6, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10, which exhibited a significant difference in the expression of these genes between normal and diseased cells, on one hand, and between the MTX-treated and untreated HFLS-RA, on the other hand.

Although we have shown that the data presented are supported by various studies cited here, the novelty of the research performed lies with the identification of these biomarkers (shortlisted from the microarrays and the inflammatory pathways) as a group with dual roles as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers. The results have demonstrated a potential improvement of an early RA diagnosis by adopting the expression profile HSPA6, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10 genes. In addition, these genes can help in predicting the therapeutic efficacy of MTX. Future studies may benefit from correlating the translation level of these proteins (HSPA6, MMP1, MMP13, and TNFSF10) to CRP.

The biomarkers identified in this study need to be tested on large diverse RA cohorts during the initial diagnosis and following their treatment with MTX using the developed multibiomarker disease activity (MBDA) test relative to clinical disease activity.32 Serum samples need to be obtained from patients and the transcription level of the 4 biomarkers can be measured and combined to generate the composite MBDA score. The relationship between the MBDA score and clinical disease activity needs to be characterized separately.

Acknowledgments

This research is the culmination of 3 PhD programmes. The authors would like to thank University of Central Lancashire, School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, for supporting this research and Dr Stefan Kotschote, Head of Laboratory of IMGM, for his analytical evaluation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LS supervised the three students, analyzed the data, co-written the manuscript. AD produced the micorarrys data and analyzed as part of his research. MS produced the RT-PCR data and analyzed as part of her research. RM produced the RT-PCR data and analyzed as part of her research. AS designed the molecular biology experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Makrygiannakis D, af Klint E, Lundberg IE, et al. Citrullination is an inflammation-dependent process. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1219–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nair SC, Jacobs JW, Bakker MF, et al. Determining the lowest optimally effective methotrexate dose for individual RA patients using their dose response relation in a tight control treatment approach. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Otterness IG. The value of C-reactive protein measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;24:91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shervington A, Cruickshanks N, Lea R, Roberts G, Dawson T, Shervington L. Can the lack of HSP90alpha protein in brain normal tissue and cell lines, rationalise it as a possible therapeutic target for gliomas? Cancer Invest. 2008;26:900–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones D, Jenny A, Swantek J, Burke J, Lauffenburger D, Sorger P. Profiling drugs for rheumatoid arthritis that inhibit synovial fibroblast activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;13:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ansorge HL, Meng X, Zhang G, et al. Type XIV collagen regulates fibrillogenesis: premature collagen fibril growth and tissue dysfunction in null mice. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8427–8438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Döring Y, Pawig L, Weber C, Noels H. The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Front Physiol. 2014;5:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ai Z, Jing W, Fang L. Cytokine-like protein 1(Cytl1): a potential molecular mediator in embryo implantation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuballa P, Baumann A, Mayer K, Bär U, Burtscher H, Brinkmann U. Induction of heat shock protein HSPA6 (HSP70B′) upon HSP90 inhibition in cancer cell lines. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1450–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Holten J, Plater-Zyberk C, Tak PP. Interferon-β for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res. 2002;4:346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srirangan S, Choy E. The role of interleukin 6 in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Therap Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2010;2:247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Churchman S, Ponchel F. IL7 in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2008;47:753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Green MJ, Gough AKS, Devlin J, et al. Serum MMP-3 and MMP-1 and progression of joint damage in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2003;42:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jüngel A, Ospelt C, Lesch M, et al. Effect of the oral application of a highly selective MMP-13 inhibitor in three different animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheumat Dis. 2010;69:898–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morel J, Audo R, Hahne M, Combe B. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) induces rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblast proliferation through mitogen-activated protein kinases and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15709–15718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Audo R, Calmon-Hamaty F, Baeten D, et al. Mechanisms and clinical relevance of TRAIL-triggered responses in the synovial fibroblasts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:904–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rica L, Urquiza JM, Gómez-Cabrero D, Islam AB. Identification of novel markers in rheumatoid arthritis through integrated analysis of DNA methylation and microRNA expression. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramirez VP, Stamatis M, Shmukler A, Aneskievich BJ. Basal and stress-inducible expression of HSPA6 in human keratinocytes is regulated by negative and positive promoter regions. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2015;20:95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hennigan S, Kavanaugh A. Interleukin-6 inhibitors in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:767–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hartgring SA, Van Roon JAG, Wijk MW, et al. Elevated expression of interleukin-7 receptor in inflamed joints mediates interleukin-7-induced immune activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2595–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Myers A, Lakey R, Cawston TE, Kay LJ, Walker DJ. Serum MMP-1 and TIMP-1 levels are increased in patients with psoriatic arthritis and their siblings. Rheumatology. 2004;43:s272–s276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Itoh T, Uzuki M, Shimamura T, Sawai T. Dynamics of matrix metallo-proteinase (MMP)-13 in the patients with RA. Rheumatism. 2002;42:60–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pei Y, Harvey A, Yu XP, Chandrasekhar S, Thirunavukkarasu K. Differential regulation of cytokine-induced MMP-1 and MMP-13 expression by p38 kinase inhibitors in human chondrosarcoma cells: potential role of Runx2 in mediating p38 effects. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tang W, Wang W, Zhang Y, Liu S, Liu Y, Zheng D. TRAIL receptor mediates inflammatory cytokine release in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Cell Res. 2009;19:758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Byeon HJ, Min SY, Kim I, et al. Human serum albumin-TRAIL conjugate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martínez-Lorenzo MJ, Anel A, Saez-Gutierrez B, et al. Rheumatoid synovial fluid T cells are sensitive to APO2L/TRAIL. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tran CN, Lundy SK, Fox DA. Synovial biology and T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Pathophysiology. 2005;12:183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Roon JAG, Jacobs K, Verstappen S, Bijlsma J, Lafeber F. Reduction of serum interleukin 7 levels upon methotrexate therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis correlates with disease suppression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1054–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fiedorczyk M, Klimiuk PA, Sierakowski S, Gindzienska-Sieskiewicz E, Chwiecko J. Serum matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in patients with early RA. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1523–1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim YH, Kang J. Effect of methotrexate on collagen-induced arthritis assessed by micro-computed tomography and histopathological examination in female rats. Biomol Ther. 2015;23:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim Y, Hooten NN, Dluzen DF, Martindale JF, Gorospe M, Evans MK. Posttranscriptional regulation of the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein by the RNA-binding protein HuR and MicroRNA 637. Mol Cell Biol 2015;35:4212–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Curtis JR, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Knevel R, et al. Validation of a novel multibiomarker test to assess rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1794–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]