Abstract

Background:

A symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus is an uncommon orthopaedic abnormality, and the majority of information in the literature is limited to small case series.

Purpose/Hypothesis:

The purpose of this study was to determine the incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci in a geographically determined population and to describe treatment trends over time. The hypothesis was that the incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci would be highest among adolescent patients, and thus, the rate of surgical treatment would be high compared with nonoperative treatment.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Methods:

The study population included 79 patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota, identified through a geographic database, who were diagnosed with a symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus between 1998 and 2015. The complete medical records were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the details of injury and treatment. Age- and sex-specific incidence rates were calculated and adjusted to the 2010 United States population.

Results:

The overall annual incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci was 3.2 (95% CI, 2.5-3.9) per 100,000 person-years; 12.6% of the patients in the cohort had bilateral symptomatic discoid lateral menisci. The overall annual incidence was similar between male (3.5 per 100,000 person-years) and female patients (2.8 per 100,000 person-years). The highest incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci was noted in adolescent male patients aged 15-18 years (18.8 per 100,000 person-years). A majority (72.2%) of patients presented with a symptomatic tear of the discoid meniscus. The remaining patients presented with mechanical symptoms, including catching/locking or effusion, with no demonstrable meniscus tear on imaging or diagnostic arthroscopic surgery. Additionally, 20.0% of patients were observed to have peripheral instability of the meniscus at the time of diagnostic arthroscopic surgery. The mean age of those with peripheral instability was significantly younger than of those who did not have peripheral instability. Sixty patients (75.9%) received surgical treatment during the study period, including 49 (81.7%) patients who underwent partial lateral meniscectomy and 11 (18.3%) patients who underwent lateral meniscus repair in addition to saucerization.

Conclusion:

With an overall annual incidence of 3.2 per 100,000 person-years, a symptomatic discoid meniscus is an uncommonly encountered orthopaedic abnormality. However, the incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci is highest in adolescent male patients. Because of the high rate of meniscus tears in patients presenting with symptoms, the majority are treated surgically.

Keywords: discoid meniscus, meniscus tear, surgical treatment, incidence

A discoid meniscus is an aberrant morphological variation of meniscus tissue, resulting in a hypertrophic and discoid-shaped configuration that can become symptomatic. An increased meniscus size and thickness, together with possible deficient peripheral attachments, can lead to meniscus instability and mechanical symptoms, resulting in “snapping knee syndrome.”12,14,15 A discoid meniscus is most commonly diagnosed in the lateral meniscus, although discoid medial menisci have been rarely reported.6,11,16

A discoid meniscus is thought to have inferior mechanical properties compared with a normal meniscus, and data suggest that patients with a discoid meniscus often present with a meniscus tear.20 A study of meniscus abnormalities in young people found that 75% of pediatric patients with isolated lateral meniscus lesions were in the setting of discoid menisci.8 Analysis of discoid meniscus tissue suggests that, aside from an abnormal macroscopic morphology, there are microscopic differences in collagen content and arrangement.1 It is hypothesized that these variations in the ultrastructural content and arrangement of discoid menisci may lead to poor vascularization and stability, which may explain their propensity to become injured.

To date, there is a paucity of data regarding the incidence and natural history of discoid menisci. Most authors estimate the overall incidence of discoid lateral menisci to be between 3% and 5% and the incidence of discoid medial menisci to be between 0.06% and 0.3%.6,11,12,16,20,27 These estimates were derived from small case series subject to selection bias; therefore, the incidence of discoid menisci (both symptomatic and asymptomatic) remains unclear.

The purposes of this study were to (1) determine the incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci in a defined geographic population stratified by age and sex and (2) describe treatment trends over time. We hypothesized that the incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci would be highest among young active patients, and because of the higher incidence of associated meniscus tears, the rate of surgical treatment would be high.

Methods

We performed a search among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, to identify all patients diagnosed with a discoid meniscus between January 1, 1998, and June 30, 2015. The data were obtained from the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), a database that provides access to complete medical records for residents of Olmsted County, which had a 2010 United States (US) census population of 144,260. This database captures all Olmsted County patients regardless of the location in the county where care was provided, ascertaining that these patients belong to a geographically defined community. The validity and generalizability of data collection using the REP system have been demonstrated previously.19,25 Patients who had International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes consistent with a discoid meniscus were identified. A full review of their medical records, including clinical notes, surgical reports, and imaging studies, was conducted by a senior orthopaedic resident (O.D.S.) to confirm the diagnosis and gather relevant data with regard to patient demographics, associated injuries, and rate of surgical interventions. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the supporting institutions.

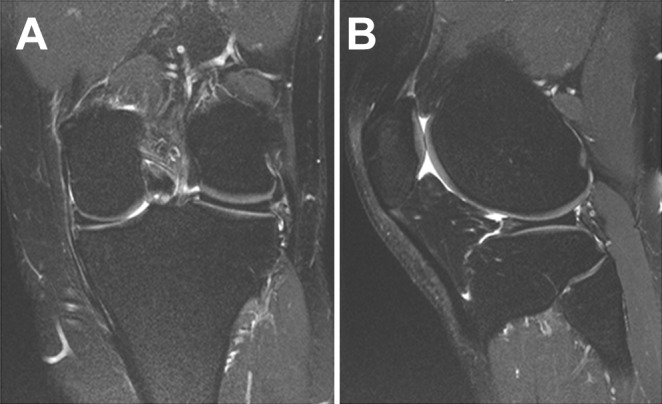

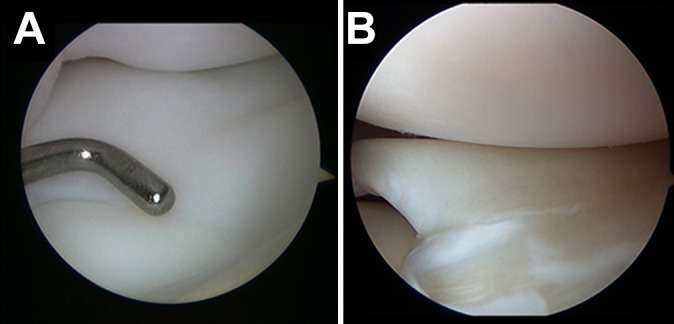

Patients were included if they presented with knee pain, mechanical symptoms (painful popping, snapping, or decreased knee extension), or meniscus injuries, and a discoid meniscus was diagnosed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or at the time of diagnostic arthroscopic surgery. A discoid meniscus was defined on MRI if the ratio of the minimal meniscal width to the maximal tibial width in the coronal plane was greater than 20% and/or if there was continuity between the anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus on ≥3 consecutive slices in the sagittal plane (Figure 1).21,27 A discoid meniscus was defined at arthroscopic surgery as a hypertrophic semilunar or discoid-shaped meniscus completely covering (Watanabe type I) or partially covering (Watanabe type II) the tibial plateau (Figure 2A) and/or if there was presence of a hypermobile meniscus as a result of deficient posterior tibial attachments (Watanabe type III or “Wrisberg variant”) (Figure 2B).26 Peripheral instability was determined from the operative report based on the surgeon’s assessment of hypermobility in response to probing. We excluded patients initially thought to have a discoid meniscus on MRI but later found to have normal meniscus tissue at the time of diagnostic arthroscopic surgery. Patients who were treated surgically were categorized into 1 of 2 groups: partial meniscectomy (including saucerization) or meniscus repair (including saucerization). Partial meniscectomy was defined as debridement of an unstable portion of the meniscus with or without reshaping of the remaining meniscus. Saucerization was defined as partial meniscectomy of intact meniscus tissue for the sole purpose of reshaping.

Figure 1.

(A) Coronal and (B) sagittal magnetic resonance imaging views of a complete discoid lateral meniscus. The ratio of the minimal meniscal width to the maximal tibial width in the coronal plane is greater than 20%. The sagittal view shows the classic “bow tie” sign.

Figure 2.

Arthroscopic view of a discoid lateral meniscus. (A) A discoid lateral meniscus with near complete coverage of the tibial plateau. (B) An unstable discoid lateral meniscus.

Statistical Analysis

Age- and sex-specific incidence rates of symptomatic discoid menisci were calculated and adjusted to the 2010 US white population. The calculation was performed using incident cases of discoid menisci as the numerator and population estimates based on the decennial census as the denominator. Only residents of Olmsted County who were diagnosed with a discoid lateral meniscus within the time interval determined in the study were counted as incident cases, and linear interpolation was performed between census years. Assuming that the yearly incidence of discoid menisci follows a Poisson distribution, we calculated incidence rates using the Poisson regression model with 95% CIs. We also calculated the rate of surgical interventions using the same methodology for each incident case of a discoid meniscus.

Results

We identified 81 patients with a diagnosis of a discoid lateral meniscus on MRI. Two patients were subsequently noted to have normal meniscus tissue at the time of diagnostic arthroscopic surgery and were excluded. Thus, we identified a cohort of 79 patients diagnosed with a symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus with a mean follow-up of 4.5 ± 2.4 years. The mean age at diagnosis was 27.4 ± 8.1 years, and 33 (41.8%) were female. Also, 12.6% of the patients had bilateral symptomatic discoid menisci in this cohort. Three patients were of Asian descent. All patients were either first seen at a tertiary sports specialty center or seen elsewhere and referred to a single tertiary sports specialty center for definitive treatment. Pediatric patients (age ≤16 years) were primarily treated by a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon, and adult patients (age ≥17 years) were primarily treated by an adult sports surgeon.

The overall age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci was 3.2 (95% CI, 2.5-3.9) per 100,000 person-years. The overall annual incidence was similar between male (3.5 per 100,000 person-years) and female patients (2.8 per 100,000 person-years). The highest incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci occurred in adolescent male patients aged 15-18 years (18.8 per 100,000 person-years) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Age- and Sex-Adjusted Annual Incidence of Symptomatic Discoid Menisci per 100,000 Person-Yearsa

| Age, y | Incidence, n | Population (Person-Years), n | Incidence Rate (Per 100,000) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | |

| 0-14 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 263,169.59 | 275,375.55 | 538,545.14 | 3.04 | 3.27 | 3.16 |

| 15-18 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 66,090.50 | 69,276.30 | 135,366.80 | 12.10 | 18.77 | 15.51 |

| 19-25 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 106,182.14 | 100,774.06 | 206,956.20 | 1.88 | 3.97 | 2.90 |

| 26-35 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 187,490.44 | 186,244.06 | 373,734.50 | 2.13 | 2.15 | 2.14 |

| 36-45 | 7 | 8 | 15 | 180,901.16 | 179,869.44 | 360,770.60 | 3.87 | 4.45 | 4.16 |

| 46-55 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 181,304.55 | 172,121.01 | 353,425.56 | 2.21 | 1.74 | 1.98 |

| 56-110 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 282,443.42 | 232,338.19 | 514,781.61 | 1.06 | 0.86 | 0.97 |

| Total | 36 | 43 | 79 | 1,267,581.80 | 1,215,998.6 | 2,483,580.40 | 2.84 | 3.54 | 3.18 |

aCalculations based on the 2010 US white population.

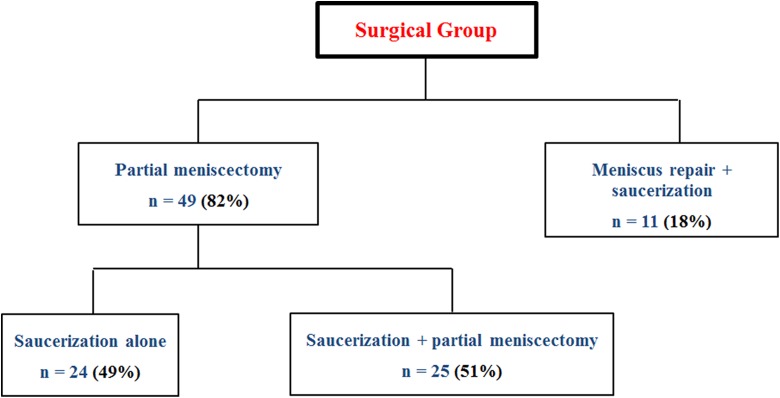

Of the 79 patients in the cohort, 57 (72.2%) presented with an associated discoid lateral meniscus tear identified on MRI or at the time of diagnostic arthroscopic surgery. Sixty patients (75.9%) received surgical treatment during the study period. Of these, 39 (65.0%) were complete discoid (type I), 15 (25.0%) were incomplete discoid (type II), and 6 (10.0%) demonstrated posterior hypermobility due to deficient posterior attachments (type III) (Table 2). Among those treated surgically, 49 (81.7%) underwent partial lateral meniscectomy, and 11 (18.3%) underwent lateral meniscus repair and saucerization of the central portion of the discoid meniscus. Of those who underwent partial lateral meniscectomy, 24 (49.0%) underwent saucerization alone (Figure 3).

TABLE 2.

Morphological Characteristics of a Discoid Lateral Meniscus

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Discoid type (n = 60) | |

| I | 39 (65) |

| II | 15 (25) |

| III | 6 (10) |

| Peripheral instability (n = 12) | |

| Anterior | 4 (33) |

| Middle | 2 (17) |

| Posterior | 6 (50) |

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients in the surgical group according to the type of procedure.

In the surgical group, 12 of the 60 patients (20.0%) were observed to have peripheral instability at the time of diagnostic arthroscopic surgery. Of these, 6 (50.0%) had posterior third instability, 4 (33.3%) had anterior third instability, and 2 (16.7%) had middle third instability (Table 2). Of those with peripheral instability, 9 (75.0%) were found to have an associated intrasubstance meniscus tear. With a mean age of 12.8 ± 8.5 years versus 30.0 ± 16.6 years, respectively, patients with peripheral instability were significantly younger than patients without peripheral instability (P < .01).

Discussion

The overall incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci in this cohort was lower compared with previously reported estimates ranging from 2% to 5%.12,22,26 Prior estimates often stem from small case series that are subject to selection bias, resulting in an overrepresentation of the true incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci. This also becomes evident once we consider that these estimates closely resemble the combined incidence rate for symptomatic and asymptomatic discoid lateral menisci of 3% to 5%, which has generally been accepted by most authors.9,12,27 Nevertheless, even these estimates are heavily dependent on the method of investigation and selection criteria, resulting in a wide range of reported incidence rates for discoid menisci between 0.4% and 20%.4,7,10,17,23 In this series, the use of a geographically defined population and chart review verification of the diagnosis may allow a more accurate estimate of the incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci.

In this cohort, the incidence of symptomatic discoid lateral menisci among young male patients was 6 times higher than the general population. Moreover, a large number of associated meniscus tears (72.2%) at the time of presentation were observed, which is consistent with prior reports noting a significantly higher rate of meniscus tears in patients with a discoid meniscus.20 A recent study analyzing the ultrastructural content of discoid menisci with transmission electron microscopy showed a discoid meniscus to have a lower number of collagen fibers and a more heterogeneous arrangement of these fibers compared with a normal meniscus.1 The authors proposed that these differences may contribute to the overall vulnerability of discoid menisci by affecting their vascularity and stability. A higher incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci in young patients could be explained if young age is interpreted as a surrogate for increased activity levels. Thus, younger, more active patients could have a higher propensity to injure an already abnormal meniscus compared with less active groups. Nevertheless, without a direct comparison with tear rates in patients with a nondiscoid meniscus, these observations require further investigation.

This cohort demonstrated a high rate of meniscus tears and a high rate of surgical treatment (75.9%) for patients presenting with a symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus. Most authors agree that surgical management for symptomatic or unstable discoid lateral meniscus tears is warranted to relieve symptoms and possibly prevent early lateral compartment wear.9,12,27 Although the choice of treatment remains highly controversial, most seem to favor meniscus preservation with repair or partial meniscectomy over total meniscectomy.12,14,27 Yet, considering the likely aberrant nature of discoid meniscus tissue and poor vascular supply, there is concern for a decreased healing potential and/or possible retearing after surgical repair. A recent systematic review evaluating surgical outcomes concluded that long-term data support saucerization over total meniscectomy but failed to demonstrate improved results with meniscus repair.24 However, available data are limited, and the decreased healing potential of discoid menisci has not been thoroughly explored.

The incidence of peripheral instability in the surgical group was 20.0%. This is comparable with reported values of 28% in prior retrospective studies.13 Additionally, patients noted to have peripheral instability were significantly younger than those without peripheral instability. Because of the high incidence of associated intrasubstance meniscus tears in those with peripheral instability, it is unclear whether the principal cause of patients’ symptoms was associated with their mechanical instability or with the meniscus tear. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that special attention should be devoted to excluding peripheral instability, particularly in young patients presenting with a symptomatic discoid meniscus.

No discoid medial menisci were observed in this cohort. This observation is in agreement with prior studies showing a greater prevalence of discoid lateral menisci, as incidence rates for discoid medial menisci have ranged from 0.06% to 0.3%.6,11,16,27 To date, there is no consensus on the likely cause of a discoid meniscus, particularly one that could more definitively explain its predilection for the lateral compartment. Some theories suggest that a discoid meniscus is the result of shear stress that results in meniscocapsular separation and secondary hypermobility, which may lead to compensatory meniscus hypertrophy.27 The lateral compartment of the knee may be more prone to this sheer stress during meniscus development because of its convex rather than concave surfaces. This could explain the higher incidence of discoid menisci on the lateral side. Moreover, the medial meniscus could be less prone to result in mechanical symptoms and/or injuries because of its relatively decreased mobility compared with the lateral meniscus.

Our cohort demonstrated a low percentage of bilateral symptomatic discoid lateral menisci (12.6%). This number is in general agreement with prior reported estimates of 20%.3 All patients in this cohort with bilateral discoid menisci presented with bilateral knee symptoms. No diagnostic studies were performed on asymptomatic contralateral knees if a discoid meniscus was diagnosed. Accordingly, the true incidence of bilateral discoid menisci is likely higher than the 12.6% reported in this study. A congenital cause of a discoid meniscus is supported by a few case reports documenting its occurrence in twins and the familial transmission of a discoid meniscus.5 Therefore, a higher rate of bilateral discoid menisci may be discovered with long-term follow-up.

The strengths of the study include the unique medical records linkage system provided by the REP, which allows almost complete ascertainment of all clinically recognized symptomatic discoid meniscus diagnoses within a well-defined population. Yet, this database may not capture patients who were misdiagnosed or who relocated outside Olmsted County and sought medical care elsewhere. Additionally, a search for the incidence of discoid menisci in all meniscus tears could have yielded a higher number of discoid meniscus cases not correctly identified with an ICD-9 code for a discoid meniscus. The REP database is composed of a mostly white population. As a result, data from our cohort may not be generalizable to other geographic regions with more ethnic diversity. For instance, a series from South Korea reported a larger incidence of bilateral discoid menisci (79%) in Asian populations,2 while the incidence of discoid menisci in the Greek population is quoted to be as low as 1.8%.18 In keeping with this observation, the incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci was calculated and adjusted to the US 2010 white population. This cohort only includes patients who presented with a symptomatic discoid meniscus, and as such, it is likely an underestimate of the true incidence of discoid menisci. Moreover, given that patients with a diagnosed discoid meniscus in 1 knee did not undergo diagnostic screening on the contralateral asymptomatic side, this work may underestimate the true incidence of bilateral discoid abnormalities.

Conclusion

A symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus remains a relatively uncommon orthopaedic abnormality, with an overall annual incidence of 3.2 per 100,000 person-years. Patients presenting with symptoms are likely to have a meniscus tear and require surgical treatment, in agreement with a general observation that discoid meniscus tissue has a higher propensity to injuries because of its aberrant morphology and composition. The incidence of symptomatic discoid menisci appears to be much higher in adolescent male patients.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: C.L.C. has received educational support from Stryker, Zimmer Biomet, and Arthrex. D.L.D. receives research support from Arthrex, and her spouse has stock/stock options in and receives royalties from Tenex Health and Sonex Health. B.A.L. receives royalties from Arthrex; is a paid consultant for Arthrex, ConMed Linvatec, and Smith & Nephew; and receives research support from Arthrex, Biomet, and Stryker. M.J.S. is a consultant for Arthrex, receives royalties from Arthrex, and receives research support from Stryker. A.J.K. receives research support from Aesculap/B. Braun, Arthrex, the Arthritis Foundation, Ceterix Orthopaedics, Histogenics, the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, and DePuy Orthopaedics; receives royalties from Arthrex; and is a consultant for Arthrex, JRF Ortho, and Vericel. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

References

- 1. Atay OA, Pekmezci M, Doral MN, Sargon MF, Ayvaz M, Johnson DL. Discoid meniscus: an ultrastructural study with transmission electron microscopy. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(3):475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bae JH, Lim HC, Hwang DH, Song JK, Byun JS, Nha KW. Incidence of bilateral discoid lateral meniscus in an Asian population: an arthroscopic assessment of contralateral knees. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):936–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellier G, Dupont JY, Larrain M, Caudron C, Carlioz H. Lateral discoid menisci in children. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Casscells SW. Gross pathological changes in the knee joint of the aged individual: a study of 300 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;(132):225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dashefsky JH. Discoid lateral meniscus in three members of a family: case reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(6):1208–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dickason JM, Del Pizzo W, Blazina ME, Fox JM, Friedman MJ, Snyder SJ. A series of ten discoid medial menisci. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(168):75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dickhaut SC, DeLee JC. The discoid lateral-meniscus syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(7):1068–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ellis HB, Jr, Wise K, LaMont L, Copley L, Wilson P. Prevalence of discoid meniscus during arthroscopy for isolated lateral meniscal pathology in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(4):285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Good CR, Green DW, Griffith MH, Valen AW, Widmann RF, Rodeo SA. Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic discoid meniscus in children: classification, technique, and results. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ikeuchi H. Arthroscopic treatment of the discoid lateral meniscus: technique and long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(167):19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeannopoulos CL. Observations on discoid menisci. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32(3):649–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jordan MR. Lateral meniscal variants: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4(4):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klingele KE, Kocher MS, Hresko MT, Gerbino P, Micheli LJ. Discoid lateral meniscus: prevalence of peripheral rim instability. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(1):79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kramer DE, Micheli LJ. Meniscal tears and discoid meniscus in children: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(11):698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kroiss F. Die Verletzungen der Kniegelenkoszwischenknorpel und ihrer Verbindungen. Beitr Klin Chir. 1910;66:598–801. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nathan PA, Cole SC. Discoid meniscus: a clinical and pathologic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;64:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noble J. Lesions of the menisci: autopsy incidence in adults less than fifty-five years old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(4):480–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papadopoulos A, Karathanasis A, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA. Epidemiologic, clinical and arthroscopic study of the discoid meniscus variant in Greek population. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(6):600–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rohren EM, Kosarek FJ, Helms CA. Discoid lateral meniscus and the frequency of meniscal tears. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30(6):316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Samoto N, Kozuma M, Tokuhisa T, Kobayashi K. Diagnosis of discoid lateral meniscus of the knee on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20(1):59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smillie IS. The congenital discoid meniscus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30:671–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smillie IS. Injuries of the Knee Joint. 4th ed Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smuin DM, Swenson RD, Dhawan A. Saucerization versus complete resection of a symptomatic discoid lateral meniscus at short- and long-term follow-up: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(9):1733–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Watanabe M, Takeda S, Ikeuchi H. Atlas of Arthroscopy. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yaniv M, Blumberg N. The discoid meniscus. J Child Orthop. 2007;1(2):89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]