Abstract

Purpose of Review

Dietary sodium is an important trigger for hypertension and humans show a heterogeneous blood pressure response to salt intake. The precise mechanisms for this have not been fully explained although renal sodium handling has traditionally been considered to play a central role.

Recent Findings

Animal studies have shown that dietary salt loading results in non-osmotic sodium accumulation via glycosaminoglycans and lymphangiogenesis in skin mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor-C, both processes attenuating the rise in BP. Studies in humans have shown that skin could be a buffer for sodium and that skin sodium could be a marker of hypertension and salt sensitivity.

Summary

Skin sodium storage could represent an additional system influencing the response to salt load and blood pressure in humans.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Salt, Skin, Sodium, VEGF-C

Introduction

Chronically elevated blood pressure, known as hypertension, represents an imminent global health challenge. Hypertension is responsible for over 10 million deaths annually and is one of the foremost modifiable risk factors for stroke, heart failure, ischaemic heart disease and chronic kidney disease [1–3]. Hypertension currently affects nearly one third of the population, and its prevalence is increasing worldwide [4]. Despite this pervasiveness, the precise origins of hypertension remain unclear, with research primarily focused on the kidney, brain, heart and blood vessels. Large population studies suggest that excessive dietary sodium, principally as the chloride salt, is an important trigger for hypertension, with the kidney considered to be the main organ regulating the haemodynamic response to salt intake [5, 6]. In this review, we examine emerging evidence supporting the role of the skin in sodium homeostasis and the regulation of blood pressure and novel extrarenal mechanisms involved in these.

Rethinking the Mechanisms for Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure (SSBP)

Salt sensitivity of blood pressure (SSBP) refers to the physiological trait by which BP of certain individuals exhibits changes parallel to changes in salt intake, while individuals without this trait are termed salt resistant [7]. SSBP is more common with greater age, Afro-Caribbean descent and individuals with hypertension, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. The variability in this trait and the mechanisms by which sodium influences blood pressure are not fully understood [7, 8]. In the classical Guytonian model, sodium intake in excess of renal excretory capacity causes an osmotically driven expansion of the extracellular fluid volume. This leads to an increase in plasma volume, venous return, and cardiac output, which in turn produce a rise in systemic blood pressure [9]. Thus, in this traditional paradigm, a defect in renal sodium excretion is the basis for salt sensitivity; conversely, salt-resistant individuals are protected from salt-induced BP rises because they can rapidly excrete a salt load without retaining sodium [10]. Others have expanded on this model, suggesting that SSBP occurs with a subnormal decrease in renal and peripheral vascular resistance in response to a high salt intake, rather than an increase in sodium retention and cardiac output, with the kidney maintaining a central role [11].

More recent studies have similarly challenged this view in humans. Schmidlin and Laffer et al. noted that both salt-resistant and salt-sensitive normotensive individuals underwent similar degrees of body sodium retention with acute dietary salt loading, demonstrating that in salt-resistant individuals, sodium retention occurred without adverse effects on BP [12, 13, 14••].These studies revealed that salt-resistant individuals can adapt to a salt load via vasodilation concomitant to increased cardiac output, while this vasodilatory response is attenuated those who are in salt sensitive [12, 13, 14••]. In general, these observations refute the view that salt sensitivity is solely due to deficiencies in renal excretion of sodium.

A ‘Three-Compartment Model’ of Body Sodium

Total body water (TBW) has historically been divided into two compartments, the intracellular fluid (ICF) and the extracellular fluid (ECF), with this latter compartment comprising the intravascular and interstitial spaces. Total body sodium (TBNa) has been similarly compartmentalised [15].While intracellular sodium and fluid volume are tightly regulated to protect cells against detrimental volume changes, the intravascular and interstitial spaces are generally believed to be in equilibrium.

Following an increase in dietary salt intake, sodium accumulates in the extracellular space. In theory, each 140 mmol of additional sodium must be coupled with the accumulation of ~ 1 l of water in the extracellular fluid to maintain osmolality. However, four carefully conducted longer-term sodium balance studies in healthy humans have shown that large amounts of sodium can accumulate without commensurate water [16–19]. Of these studies, the Mars 500 study, which investigated sodium metabolism at constant salt intake under controlled conditions for either 105 or 250 days, showed that sodium is rhythmically stored and released independent of salt intake, and that BP, body weight and extracellular water were not coupled to urine sodium excretion as expected [19]. A further study, which assessed sodium and water excretion in healthy humans after infusion with hypertonic saline, found that sodium recovery in the urine was only half of the expected amount, indicating that some of the infused sodium was retained in an osmotically inactivated form [20••]. These observations support the existence of non-osmotic storage of excess sodium (sodium accumulation without commensurate water retention) in an additional third compartment, suggesting the existence of ‘extra-renal’ mechanisms for sodium homeostasis.

The Skin as a ‘Third Compartment’ of Body Sodium and Relevance to BP

The skin is the largest organ in the human body, comprising 6% of body weight and forming a significant component of the interstitium [21, 22]. The skin consists of two tissue layers: the epidermis, the external layer consisting of non-stratified epithelial cells and the dermis, which consists mainly of connective tissue [22]. The epidermis is approximately 50–200 μm thick and acts as a physical barrier against microorganisms and water loss, while the dermis is relatively acellular, comprised of fibroblasts, blood vessels, lymphatics and nerves in an extracellular matrix of collagen, elastin and glycosaminoglycans [22, 23]. The skin is a rich source of nitric oxide, a major regulator of vascular tone, containing ten times the levels in the circulation [24]. Blood flow in the skin is dynamic, ranging from as low as 1% in cold temperatures to as high as 60% in erythroderma and heat stress [25, 26••]. These properties of the skin would suggest the potential for influencing systemic BP [25, 26••].

From as early as 1909, direct chemical measurements indicated that the skin is a depot for sodium, chloride and water, although the exact relevance of skin electrolytes was not known [27–30]. In 1978, Ivanova et al. showed that skin sodium in white rats increased with dietary salt loading and observed that this was associated with an increase in sulphated glycosaminoglycans [31]. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are linear polysaccharide chains of variable length consisting of repeating disaccharide units [32, 33]. Due to the presence of carboxyl and sulphate functional groups on the disaccharide units, GAGs possess significant negative charge densities capable of facilitating the non-osmotic storage of sodium in the interstitium, as described in a recent comprehensive review [34••]. It should be noted that the skin is not the only place with high glycosaminoglycan content, and non-osmotic sodium storage can occur elsewhere in the interstitium.

In 2002, Titze et al. first proposed the connection between skin sodium, GAGs and BP following a series of rat experiments [35–39]. Work by this group revealed that GAG polymerisation facilitates osmotically inactive sodium storage in the skin, enabling skin sodium concentrations to rise as much as 180–190 mmol/l without commensurate increases in skin water content. This osmotically inactive sodium storage could therefore serve as a mechanism for buffering volume and blood pressure following changes in salt intake [36–39].

Titze et al. calculated that osmotically inactive sodium storage in salt-resistant rats was threefold higher than in salt-sensitive rats, based on body sodium and body water measurements [35]. They further demonstrated that male rats had a higher capacity for osmotically inactive skin sodium storage compared to fertile female rats, while ovariectomised rats had no capacity for osmotically inactive sodium accumulation [36]. The above findings led to the conclusion that the skin functions a ‘third compartment’ of body sodium, with a dynamic capacity for sodium storage and buffering volume and blood pressure changes with salt intake.

Tissue Macrophages and the Lymphatics Influence Sodium Balance, Interstitial Volume and Blood Pressure

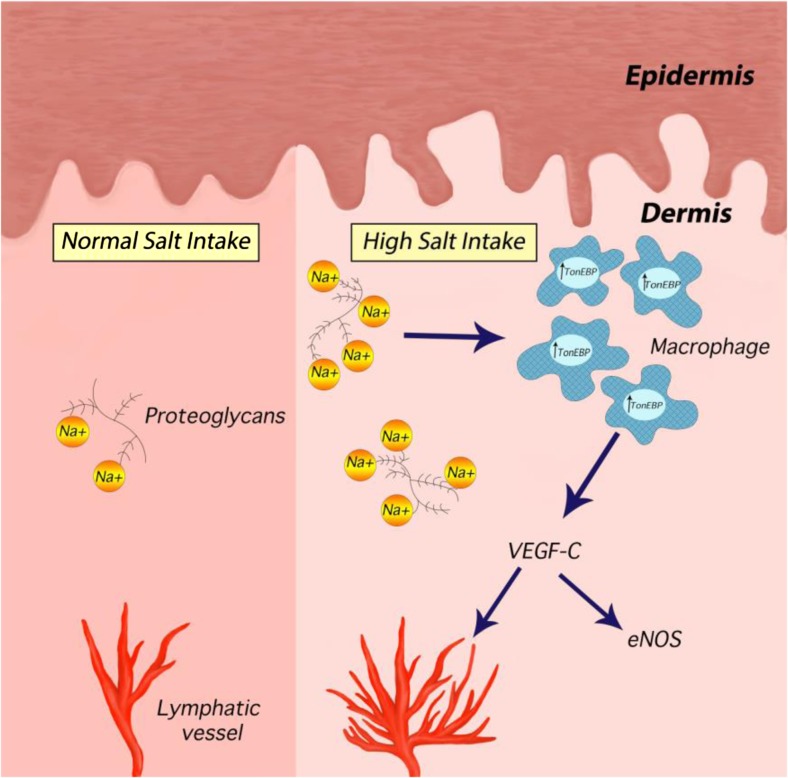

In recent years, it has become apparent that cells of the innate and adaptive immune system play a role in hypertension and cardiovascular disease [40]. Work in rodent skin has showed that macrophages mediate an additional adaptive mechanism that functions during periods of high salt intake (Fig. 1) [38, 39, 41]. Following salt challenge, skin sodium concentration increased and the resultant hypertonicity caused recruitment of macrophages which activated tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein (TonEBP). TonEBP increased the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) gene via autocrine signalling. By mediating VEGF-C, the macrophage response restructured the interstitial lymphatic network, enabling drainage of water and electrolytes from the skin into the systemic circulation. VEGF-C also and induced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), causing vasodilation via nitric oxide (NO) production. These processes evidently serve to buffer the haemodynamic effects to salt loading [38]. VEGF-C and TonEBP antagonism and genetic deletion and consequent disruption of the above pathway caused salt sensitivity in these rodents [38, 39, 41].

Fig. 1.

A novel extra-renal mechanism for buffering dietary salt. Under normal conditions, Na+ binds to negatively charged GAGs in the dermal interstitium, without commensurate water, allowing high concentrations of Na+ to accumulate in the skin. During salt loading, the Na+-binding capacity of GAGs is exceeded and interstitial hypertonicity develops. This leads to an influx of macrophages, which release an osmosensitive transcription factor (TonEBP). This induces the secretion of VEGF-C in an autocrine manner, leading to lymphangiogenesis. The enhanced lymphatic network increases Na+ transport back into the circulation, for eventual removal by the kidneys, preventing a blood pressure rise with salt loading (Adapted from Marvar et al. [42]. Illustrated by Gökçen Ackali)

In summary, macrophages exert a homeostatic function in the skin via TonEBP and VEGF-C, regulating clearance of osmotically inactive stored salt via cutaneous lymphatic vessels, buffering the haemodynamic response to dietary salt. In this process, the lymphatics serve as a connection between skin as a ‘third compartment’ of body sodium and the circulation and this appears to be mediated by VEGF-C.

Recent Evidence for the Role of the Skin in Sodium Homeostasis and BP Regulation in Humans

Most of the novel mechanisms described above linking dietary salt, skin sodium, and BP were examined in rodent models. The rest of this review will focus on recent studies examining skin sodium in humans, its relevance to human sodium homeostasis and BP regulation and possible mechanisms linking these.

Insights from Sodium MRI of the Skin in Humans

For over 30 years, the use of 23Na-MRI spectroscopy has enabled non-invasive in vivo assessment of sodium concentrations in human tissue [43]. Recently, researchers have begun using 23Na-MRI spectroscopy to measure sodium in calf skin and muscle alongside water measurements using traditional proton MRI [44, 45, 46••, 47, 48, 49••].

Initial experiments showed that skin sodium was positively correlated with age, and that men had higher skin sodium than women after controlling for both age and BMI [44, 45, 48]. In cross-sectional studies on normotensives and hypertensives, Kopp et al. have shown that skin sodium was positively associated with BP, patients with refractory hypertension had increased tissue Na+ content compared to controls, and there was a trend for increased skin sodium in individuals with hyperaldosteronism [44, 45].

In 2014, Dahlmann et al. investigated the role of the skin as a sodium buffer using 23Na-MRI in 24 haemodialysis patients before and after a single dialysis. Skin sodium was reduced by 19% following dialysis, and patients with higher serum VEGF-C levels had better dialytic Na+ removal [46••]. Skin sodium was also higher in haemodialysis patients compared to healthy controls, and they noted an age-related rise in skin Na+ which corresponded to a decline in serum VEGF-C. The authors concluded that skin Na+ stores can be mobilised by haemodialysis, and VEGF-C facilitates Na+ flow between the interstitium and systemic circulation in humans, supporting earlier work in rodents [38, 46••]. More recently, Kopp et al. showed that type 2 diabetics on haemodialysis had significantly higher skin sodium compared with their non-diabetic counterparts [50••].

Schneider et al. used Na MRI to investigate the potential role of skin Na+ as a biomarker for hypertensive target-organ damage, further demonstrating that skin sodium content positively correlated with systolic BP and was a strong, independent predictor of left ventricular mass (LVM) in 89 participants with mild renal impairment [49••]. In these patients, skin sodium was independent of sex, height, SBP and body hydration as measured by bioimpedence.

In summary, cross-sectional data from 23Na-MRI studies in humans show that higher skin sodium storage is associated with higher BP and target organ damage. Skin sodium appears to be higher in older individuals, hypertensives, haemodialysis patients and diabetics—all groups previously known to have the SSBP trait. Skin sodium changes during dialysis support its role as a buffer for body sodium. VEGF-C appears to determine skin sodium in humans, potentially via lymphangiogenesis facilitating the efflux of sodium. Sex-specific differences in skin Na+ are interesting, but their relevance is currently unclear. Thus, it can be seen that 23Na MRI has provided important insights into the relevance of skin Na+ in humans.

Insights from Direct Chemical Analysis of the Skin Sodium in Humans

Although MRI data were confirmed by direct ashing of human cadaveric samples, they have not yet been confirmed by direct chemical analysis of skin electrolytes in humans [44]. In the past year, two studies have evaluated skin electrolytes in humans using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), a highly sensitive analytical tool capable of simultaneous multi-elemental determinations down to the sub-parts-per-billion level [51, 52••, 53••]. Fischereder et al. measured tissue Na+ and GAG content in skin and arterial samples taken from renal transplant donors and recipients [52••]. They showed that skin and arterial Na+ concentration correlated with GAG content, suggesting that interstitial Na+ storage is regulated by GAGs in humans, and this could function in the buffering of dietary salt. They also found that skin Na+ correlated well with arterial Na+, indicating a possible link between the systemic vasculature and the skin with regard to sodium homeostasis.

We recently assessed skin electrolytes, blood pressure and plasma VEGF-C in 48 healthy participants (24 men) taking placebo (70 mmol sodium/day) and slow sodium (200 mmol/day) for 7 days in a double-blind, randomised, cross-over study [53••]. Skin Na+, expressed as the ratio Na+:K+, was 8% higher following the slow sodium phase. Post hoc analysis revealed a sex-specific effect, wherein men experienced a significant 11.2% increase in skin Na+:K+ following the slow sodium phase while women did not (4%). Women showed a significant increase in 24-h mean arterial blood pressure and body weight with salt loading while men did not. We concluded that skin sodium increases with dietary salt loading and this may be influenced by sex. Women showed a trend for less skin Na+ accumulation of salt loading and greater salt sensitivity of BP, in keeping with previous studies in rodents showing the skin functions as a buffer for dietary sodium [35–39]. We hypothesised that the sex differences observed could be due to sex-specific skin structural differences in thickness and GAG content and men having a greater capacity for passage of Na+ through the skin than women [54, 55]. In this study, skin Na+:K+ positively correlated with BP and peripheral vascular resistance (PVR), in support of recent 23Na MRI data showing a positive correlation between BP and skin Na+ [45, 49]. This was seen in men only, possibly due to variability in skin K+ and hence the Na+:K+ ratio with contraceptive treatment in women [53••]. No significant changes in plasma VEGF-C were observed between placebo and slow sodium phases to support a clear involvement of Ton-EBP or VEGF-C activation in this study.

Potential Mechanisms Linking Skin Sodium and Blood Pressure

The exact basis for the relationship between skin sodium and BP is unknown. These parameters could be linked to a common yet unknown aetiological factor. Alternatively, skin sodium could mediate changes in haemodynamics either directly or through other substances. The Ton-EBP-VEGF-C axis has been shown to mediate BP in dietary salt loading. Several other mechanisms could explain the link between skin sodium and haemodynamics.

Skin capillary rarefaction, the reduction in the density of capillaries, and has been associated with hypertension [56–58]. Capillary rarefaction is believed to be structural in origin, associated with either impaired angiogenesis or capillary attrition and is believed to mediate BP changes by altering PVR [57]. He et al. showed that in hypertensive humans, a modest reduction in salt intake improves dermal capillary density as assessed by capillaroscopy [58]. This trend was seen across different racial groups and suggests that salt intake is linked to microvascular rarefaction. The exact mechanisms whereby salt affects the microcirculation remain unclear, with recent work in rats suggesting that skin sodium accumulation during high salt intake increases vasoreactivity in the skin [59].

The hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) transcription system, acting via the heterodimeric transcription factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α, plays a central role in the cellular response to hypoxia [60]. Recent evidence suggests that the HIF-1α:HIF-2α ratio in the skin affects synthesis of nitric oxide synthase 2(NOS 2), a key regulator of vascular tone [61]. HIF-1α and HIF-2a act antagonistically—HIF-1a promotes nitric oxide production by keratinocytes via NOS 2 while HIF-2α promotes keratinocyte arginase expression and urea production [62]. Cowburn et al. recently showed that mice with keratinocyte HIF-1α deletion had increased vascular tone and elevated systemic BP. Conversely, deletion of HIF-2α activity in keratinocytes resulted in increased skin NO levels and reduced systemic BP [61]. In accordance with this, they showed decreased epidermal expression of HIF-1α and increased epidermal HIF-2α expression in hypertensive humans correlated significantly with increased mean blood pressure. These findings provide a novel mechanism for systemic BP regulation by the skin. Recent evidence in rodents suggests that HIF metabolism may also be influenced by dietary salt. In the renal medulla dietary salt suppresses HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 (PHD2), which degrades HIF-1α and HIF-2α, increasing natriuresis [63, 64]. If high salt intake could similarly alter levels of HIF isomers in the skin, this would potentially influence PVR. This would need to be explored in further work.

Movement of Dietary Sodium into the Skin—How and Why Does It Get There?

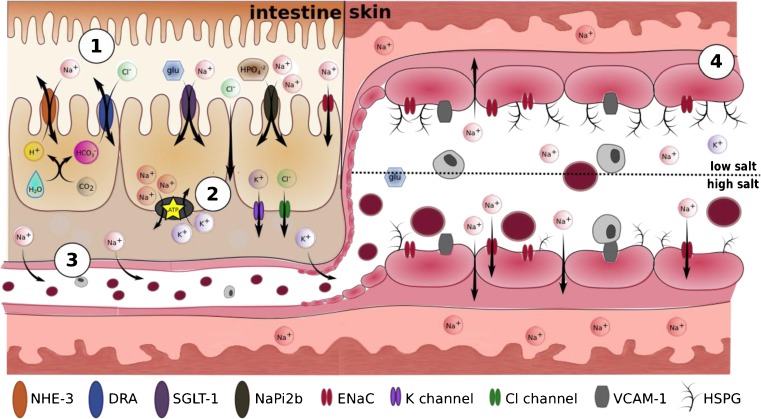

To reach the skin, dietary sodium must first transit through the intestine, the blood stream and then out into the dermal interstitium (Fig. 2). Sodium absorption across the apical membrane of enterocytes and colonocytes is broadly facilitated by three mechanisms: (1) sugar and phosphate co-transport via SGLT1, GLUT and NaPi2b; (2) electroneutral proton exchange via NHE-2, NHE-3, and NHE-8 and (3) passive diffusion via the sodium channel ENaC [65–69]. This latter mechanism is predominantly localised to the colon.

Fig. 2.

Movement of sodium from the intestinal lumen to the skin. [1] Intestinal sodium absorption across the apical membrane of enterocytes is facilitated by (i) Na-H exchange (NHE-2, NHE-3, NHE-8), (ii) cotransport with sugars and phosphates (SGLT-1, GLUT, NaPi2b) and (iii) diffusion through endothelial Na channels (ENaC). Chloride transport occurs via bicarbonate exchange (DRA) and paracellular diffusion. [2] Intracellular sodium is actively pumped across the basal membrane of the intestine by Na-K ATPases. [3] Once in the interstitium, sodium diffuses into the intestinal capillaries for transport through the vasculature. [4] Sodium can diffuse paracellularly into the skin under low salt conditions. Consuming excessive amounts of salt can exaggerate this process by causing damage to the endothelial glycocalyx and reducing barrier effectiveness

In contrast, chloride absorption is largely mediated by paracellular diffusion and apical bicarbonate exchange via downregulated-in-adenoma (DRA) proteins. This bicarbonate exchange is coupled to NHE-mediated sodium absorption, effectively marrying Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− exchange [70]. Intracellular chloride can diffuse out of enterocytes through chloride channels.

Intracellular sodium is actively pumped across the basolateral membrane and into the extracellular space by sodium-potassium ATPases, which export three sodium ions from the cell in exchange for two potassium ions. The requisite extracellular potassium concentrations are maintained by diffusion of intracellular potassium through basolateral potassium channels. After concentration in the extracellular space, sodium can diffuse into the intestinal capillaries for transport throughout the body. It is not clear whether these various sodium, chloride and potassium transporters play a role in sodium sensitivity.

What drives sodium out of vasculature and into the skin specifically is not well understood, and the transit route from vascular lumen to dermis is likewise speculative. When transitioning out of the vascular lumen, sodium first encounters the endothelial glycocalyx. Comprised primarily of heparan sulphate proteoglycans (HSPGs), this delicate layer varies in thickness from 0.5 to 4.5 μm [71]. The anionic character of this glycocalyx facilitates smooth red blood cell movement, inhibits white blood cell adhesion, scavenges oxygen free radicals and can help detect small changes in blood pressure and trigger a vasodilatory response [71, 72].

Excessive dietary sodium consumption may damage this glycocalyx and promote sodium ‘leakage’. In vitro experiments have shown that chronic exposure of endothelial cells to 150 mM sodium decreased glycocalyx HSPGs by 68% and caused endothelial stiffening [73, 74]. This damaged glycocalyx could facilitate excessive sodium movement into the interstitium via paracellular diffusion and increased exposure to or increased activation of vascular ENaC channels [75]. Additionally, glycocalyx damage and endothelial stiffening may increase leucocyte adhesion and infiltration, further damaging the vessel wall [73, 75, 76].

From current data, it is not immediately clear whether the skin acts as a pre-emptive reservoir for excessive sodium, removing it from circulation before it can induce adverse cardiovascular effects, or if the skin functions as an overflow reservoir once the excessive sodium has caused sufficient vascular damage to ‘leak’ into the surrounding tissue. Regardless, once in the skin, the positively charged sodium is osmotically inactivated through association with anionic GAGs. The presence of high concentrations of sodium can stimulate increased GAG synthesis, expanding the storage capacity of this osmotically inactive third compartment.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The skin acts as a third compartment for sodium, capable of non-osmotic sodium storage and mediating a vasodilatory response via VEGF-C. This appears to constitute an extra-renal mechanism controlling blood pressure during high salt intake. Incorporating this model into the traditional paradigm of sodium homeostasis, the skin may act as a buffer as well as a reservoir for sodium, while the kidney controls sodium excretion and reabsorption, controlling serum osmolality and total body water. It is conceivable that people predisposed to salt-sensitive hypertension have defects in the pathways described above. What is less understood is why skin sodium accumulation with short-term dietary salt loading appears to protect from a rise in BP rise, but long-term high skin sodium is associated with higher BP and the propensity for SSBP. A potential explanation could be that impaired VEGF-C-induced lymphangiogenesis in these individuals reduces efflux of sodium from the skin to the systemic circulation and attenuates the vasodilatory response to salt loading. Further work is needed to explore this and other mechanisms that could be involved. The exact mechanisms underlying the movement of dietary sodium from the gut to the vasculature and the skin are yet unclear. Future challenges include ascertaining how different antihypertensive agents affect the distribution of sodium and water between the skin and the intravascular space and how this system interacts with other organs that modulate BP like the kidney and brain.

Funding Information

VS has been funded by the British Heart Foundation and Addenbrookes Charitable Trust. IBW is funded by the British Heart Foundation and NIHR.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

VS, CM and IBW were involved in a study involving humans (Reference 55). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from a National Research Ethics Committee (REC Reference 11/H0304/003) and was performed according to Good Clinical Practice and according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Blood Pressure Monitoring and Management

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major Importance

- 1.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365(9455):217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawes CM, Hoorn SV, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–2323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, Chen J, He J. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Intersalt Cooperative Research Group Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24-hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. Br Med J. 1988;297(6644):319–328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6644.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mente A, O'Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen M, Poirier P, Wielgosz A, Morrison H, Li W, Wang X, di C, Mony P, Devanath A, Rosengren A, Oguz A, Zatonska K, Yusufali AH, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Avezum A, Ismail N, Lanas F, Puoane T, Diaz R, Kelishadi R, Iqbal R, Yusuf R, Chifamba J, Khatib R, Teo K, Yusuf S, PURE Investigators Association of Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion with Blood Pressure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):601–611. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elijovich F, Weinberger MH, Anderson CAM, Appel LJ, Bursztyn M, Cook NR, Dart RA, Newton-Cheh CH, Sacks FM, Laffer CL, American Heart Association Professional and Public Education Committee of the Council on Hypertension; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; and Stroke Council Salt sensitivity of blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2016;68(3):e7–e46. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh YS, Appel LJ, Galis ZS, Hafler DA, He J, Hernandez AL, Joe B, Karumanchi SA, Maric-Bilkan C, Mattson D, Mehta NN, Randolph G, Ryan M, Sandberg K, Titze J, Tolunay E, Toney GM, Harrison DG. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group report on salt in human health and sickness: building on the current scientific evidence. Hypertension. 2016;68(2):281–288. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyton AC. Blood pressure control—special role of the kidneys and body fluids. Science. 1991;252(5014):1813–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.2063193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyton AC. Long-term arterial pressure control: an analysis from animal experiments and computer and graphic models. Am J Phys. 1990;259(5 Pt 2):R865–R877. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.5.R865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris RC, Schmidlin O, Sebastian A, et al. Vasodysfunction that involves renal Vasodysfunction, not abnormally increased renal retention of sodium, accounts for the initiation of salt-induced hypertension. Circulation. 2016;133:881–883. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidlin O, Forman A, Sebastian A, Morris RC. What initiates the pressor effect of salt in salt-sensitive humans?: observations in normotensive blacks. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1032–1039. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidlin O, Forman A, Leone A, Sebastian A, Morris RC. Salt sensitivity in blacks: evidence that the initial pressor effect of NaCl involves inhibition of vasodilatation by asymmetrical dimethylarginine. Hypertension. 2011;58(3):380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laffer CL, Scott RC, Titze JM, Luft FC, Elijovich F. Hemodynamics and salt-and-water balance link sodium storage and vascular dysfunction in salt-sensitive subjects. Hypertension. 2016;68(1):195–203. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhave G, Neilson EG. Body fluid dynamics: back to the future. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(12):2166–2181. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heer M, Baisch F, Kropp J, Gerzer R, Drummer C. High dietary sodium chloride consumption may not induce body fluid retention in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(4):F585–F595. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.4.F585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palacios C, Wigertz K, Martin BR, et al. Sodium retention in black and white female adolescents in response to salt intake. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2009;89(4):1858–1863. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Titze J, Maillet A, Lang R, Gunga HC, Johannes B, Gauquelin-Koch G, Kihm E, Larina I, Gharib C, Kirsch KA. Long-term sodium balance in humans in a terrestrial space station simulation study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(3):508–516. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakova N, Jüttner K, Dahlmann A, Schröder A, Linz P, Kopp C, Rauh M, Goller U, Beck L, Agureev A, Vassilieva G, Lenkova L, Johannes B, Wabel P, Moissl U, Vienken J, Gerzer R, Eckardt KU, Müller DN, Kirsch K, Morukov B, Luft FC, Titze J. Long-term space flight simulation reveals infradian rhythmicity in human Na+ balance. Cell Metab. 2013;17(1):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olde Engberink RHG, Rorije NMG, van den Born B-JH, Vogt L. Quantification of nonosmotic sodium storage capacity following acute hypertonic saline infusion in healthy individuals. Kidney Int. 2017;91(3):738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aukland K, Reed RK. Interstitial-lymphatic mechanisms in the control of extracellular fluid volume. Physiol Rev. 1993;73(1):1–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobin DJ. Biochemistry of human skin—our brain on the outside. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35(1):52–67. doi: 10.1039/B505793K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldsmith LA. Physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology of the skin. USA: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mowbray M, McLintock S, Weerakoon R, Lomatschinsky N, Jones S, Rossi AG, Weller RB. Enzyme-independent NO stores in human skin: quantification and influence of UV radiation. J Investig Dermatol. 2009;129(4):834–842. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charkoudian N. Skin blood flow in adult human thermoregulation: how it works, when it does not, and why. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):603–612. doi: 10.4065/78.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RS, Titze J, Weller R. Cutaneous control of blood pressure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25(1):11–15. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahlgren V, Magnus R. Über die Bedeutung der Gewebe als Chlordepots. Archiv Experiment Pathol Pharmakol. 1909;61(2–3):97–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01841955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbach E, LeWinn EB. Skin diseases, nutrition and metabolism. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1946. p. 23–24.

- 29.Eisele CW, Eichelberger L. Water, electrolyte and nitrogen content of human skin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1945;58(1):97–100. doi: 10.3181/00379727-58-14856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carruthers C. Biochemistry of skin in health and disease. American 552 lecture series 505. IIllinois: Charles C Thomas; 1962. p. 131–147.

- 31.Ivanova LN, Archibasova VK, IS S. Sodium-depositing function of the skin in white rats. Fiziol Zh SSSR Im I M Sechenova. 1978;64(3):358–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comper WD, Laurent TC. Physiological function of connective tissue polysaccharides. Physiol Rev. 1978;58(1):255–315. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaefer L, Schaefer RM. Proteoglycans: from structural compounds to signaling molecules. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339(1):237–246. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0821-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiig H., Luft F. C., Titze J. M. The interstitium conducts extrarenal storage of sodium and represents a third compartment essential for extracellular volume and blood pressure homeostasis. Acta Physiologica. 2017;222(3):e13006. doi: 10.1111/apha.13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Titze J, Krause H, Hecht H, Dietsch P, Rittweger J, Lang R, Kirsch KA, Hilgers KF. Reduced osmotically inactive Na storage capacity and hypertension in the Dahl model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283(1):F134–F141. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00323.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Titze J, Lang R, Ilies C, Schwind KH, Kirsch KA, Dietsch P, Luft FC, Hilgers KF. Osmotically inactive skin Na+ storage in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285(6):F1108–F1117. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00200.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Titze J, Shakibaei M, Schafflhuber M, Schulze-Tanzil G, Porst M, Schwind KH, Dietsch P, Hilgers KF. Glycosaminoglycan polymerization may enable osmotically inactive Na+ storage in the skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(1):H203–H208. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01237.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Dahlmann A, Tammela T, Machura K, Park JK, Beck FX, Müller DN, Derer W, Goss J, Ziomber A, Dietsch P, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Kurtz A, Hilgers KF, Alitalo K, Eckardt KU, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C–dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med. 2009;15(5):545–552. doi: 10.1038/nm.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machnik A, Dahlmann A, Kopp C, Goss J, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Eckardt KU, Muller DN, Park JK, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J. Mononuclear phagocyte system depletion blocks interstitial tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein/vascular endothelial growth factor C expression and induces salt-sensitive hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 2010;55(3):755–761. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.143339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison DG. Vascular inflammatory cells in hypertension. Front Physiol. 2012;3:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiig H, Schröder A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Kopp C, Karlsen TV, Boschmann M, Goss J, Bry M, Rakova N, Dahlmann A, Brenner S, Tenstad O, Nurmi H, Mervaala E, Wagner H, Beck FX, Müller DN, Kerjaschki D, Luft FC, Harrison DG, Alitalo K, Titze J. Immune cells control skin lymphatic electrolyte homeostasis and blood pressure. J Clin Investig. 2013;123(7):2803–2815. doi: 10.1172/JCI60113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marvar PJ, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Blood pressure control: salt gets under your skin. Nat Med. 2009;15(5):487–488. doi: 10.1038/nm0509-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hilal SK, Maudsley AA, Ra JB, Simon HE, Roschmann P, Wittekoek S, Cho ZH, Mun SK. In vivo NMR imaging of sodium-23 in the human head. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kopp C, Linz P, Wachsmuth L, Dahlmann A, Horbach T, Schöfl C, Renz W, Santoro D, Niendorf T, Müller DN, Neininger M, Cavallaro A, Eckardt KU, Schmieder RE, Luft FC, Uder M, Titze J. 23Na magnetic resonance imaging of tissue sodium. Hypertension. 2011;59(1):167–172. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.183517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kopp C, Linz P, Dahlmann A, et al. 23Na magnetic resonance imaging-determined tissue sodium in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;61(3):635–640. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dahlmann A, Dörfelt K, Eicher F, Linz P, Kopp C, Mössinger I, Horn S, Büschges-Seraphin B, Wabel P, Hammon M, Cavallaro A, Eckardt KU, Kotanko P, Levin NW, Johannes B, Uder M, Luft FC, Müller DN, Titze JM. Magnetic resonance–determined sodium removal from tissue stores in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2014;87(2):434–441. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linz P, Santoro D, Renz W, Rieger J, Ruehle A, Ruff J, Deimling M, Rakova N, Muller DN, Luft FC, Titze J, Niendorf T. Skin sodium measured with 23Na MRI at 7.0 T. NMR Biomed. 2014;28(1):54–62. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang P, Deger MS, Kang H, Ikizler TA, Titze J, Gore JC. Sex differences in sodium deposition in human muscle and skin. Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;36:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider MP, Raff U, Kopp C, Scheppach JB, Toncar S, Wanner C, Schlieper G, Saritas T, Floege J, Schmid M, Birukov A, Dahlmann A, Linz P, Janka R, Uder M, Schmieder RE, Titze JM, Eckardt KU. Skin sodium concentration correlates with left ventricular hypertrophy in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1867–1876. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016060662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kopp C, Linz P, Maier C, Wabel P, Hammon M, Nagel AM, Rosenhauer D, Horn S, Uder M, Luft FC, Titze J, Dahlmann A. Elevated tissue sodium deposition in patients with type 2 diabetes on hemodialysis detected by 23Na magnetic resonance imaging. Kidney Int. 2018;93(5):1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hou X, Jones BT. Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry. In: Myers RA, editor. Encyclopedia of analytical chemistry. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. 2000. p. 9468–9485.

- 52.Fischereder M, Michalke B, Schmöckel E, Habicht A, Kunisch R, Pavelic I, Szabados B, Schönermarck U, Nelson PJ, Stangl M. Sodium storage in human tissues is mediated by glycosaminoglycan expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313(2):F319–F325. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00703.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Selvarajah V, Mäki-Petäjä KM, Pedro L, Bruggraber SFA, Burling K, Goodhart AK, Brown MJ, McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB. Novel mechanism for buffering dietary salt in humans: effects of salt loading on skin sodium, vascular endothelial growth factor C, and blood pressure. Hypertension. 2017;70(5):930–937. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giacomoni PU, Mammone T, Teri M. Gender-linked differences in human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55(3):144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh J-H, Kim YK, Jung J-Y, Shin J-E, Chung JH. Changes in glycosaminoglycans and related proteoglycans in intrinsically aged human skin in vivo. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20(5):455–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasad A, Dunnill GS, Mortimer PS, MacGregor GA. Capillary rarefaction in the forearm skin in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1995;13(2):265–268. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antonios TFT, Singer DRJ, Markandu ND, Mortimer PS, MacGregor GA. Structural skin capillary rarefaction in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33(4):998–1001. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.33.4.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He FJ, Marciniak M, Markandu ND, Antonios TF, MacGregor GA. Effect of modest salt reduction on skin capillary rarefaction in white, Black, and Asian Individuals with Mild Hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;56(2):253–259. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Helle F, Karlsen TV, Tenstad O, Titze J, Wiig H. High salt diet increases hormonal sensitivity in skin pre-capillary resistance vessels. Acta Physiol. 2013;207(3):577–581. doi: 10.1111/apha.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maxwell PH, Eckardt K-U. HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors for the treatment of renal anaemia and beyond. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(3):157–168. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cowburn AS, Takeda N, Boutin AT, Kim JW, Sterling JC, Nakasaki M, Southwood M, Goldrath AW, Jamora C, Nizet V, Chilvers ER, Johnson RS. HIF isoforms in the skin differentially regulate systemic arterial pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(43):17570–17575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306942110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeda N, O'Dea EL, Doedens A, et al. Differential activation and antagonistic function of HIF-alpha isoforms in macrophages are essential for NO homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2010;24(5):491–501. d. doi: 10.1101/gad.1881410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Z, Zhu Q, Xia M, Li PL, Hinton SJ, Li N. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl-hydroxylase 2 senses high-salt intake to increase hypoxia inducible factor 1 levels in the renal medulla. Hypertension. 2010;55(5):1129–1136. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu Q, Hu J, Han W-Q, Zhang F, Li PL, Wang Z, Li N. Silencing of HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 gene in the renal medulla attenuates salt-sensitive hypertension in Dahl S rats. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(1):107–113. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu H, Chen R, Ghishan FK. Subcloning, localization, and expression of the rat intestinal sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 8. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289(1):G36–G41. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00552.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Collins JF, Xu H, Kiela PR, Zeng J, Ghishan FK. Functional and molecular characterization of NHE3 expression during ontogeny in rat jejunal epithelium. Am J Phys. 1997;273(6 Pt 1):C1937–C1946. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Collins JF, Honda T, Knobel S, Bulus NM, Conary J, DuBois R, Ghishan FK. Molecular cloning, sequencing, tissue distribution, and functional expression of a Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE-2) PNAS. 1993;90(9):3938–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cuppoletti John, Malinowska Danuta H. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 2012. Ion Channels of the Epithelia of the Gastrointestinal Tract; pp. 1863–1876. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. Recent advances in the renal-skeletal-gut axis that controls phosphate homeostasis. Lab Investig. 2009;89(1):7–14. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. Physiology of intestinal absorption and secretion. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30(2):145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reitsma S, Slaaf DW, Vink H, van Zandvoort MAMJ, oude Egbrink MGA. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2007;454(3):345–359. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weinbaum S, Tarbell JM, Damiano ER. The structure and function of the endothelial glycocalyx layer. Annu Rev Bioeng. 2007;9(1):121–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oberleithner H, Peters W, Kusche-Vihrog K, Korte S, Schillers H, Kliche K, Oberleithner K. Salt overload damages the glycocalyx sodium barrier of vascular endothelium. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2011;462(4):519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oberleithner H, Riethmueller C, Schillers H, Macgregor GA, de Wardener HE, Hausberg M. Plasma sodium stiffens vascular endothelium and reduces nitric oxide release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(41):16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Korte S, Wiesinger A, Straeter AS, Peters W, Oberleithner H, Kusche-Vihrog K. Firewall function of the endothelial glycocalyx in the regulation of sodium homeostasis. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2012;463(2):269–278. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1038-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McDonald KK, Cooper S, Danielzak L, Leask RL. Glycocalyx degradation induces a proinflammatory phenotype and increased leukocyte adhesion in cultured endothelial cells under flow. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]