Flagellar biogenesis is a highly orchestrated event where the flagellar structure spans the bacterial cell envelope. The rod diameter of approximately 4 nm is larger than the estimated pore size of the peptidoglycan layer; hence, its insertion requires the localized and controlled lysis of the cell wall. We found that a 47-residue domain of the C terminus of the lytic transglycosylase (LT) SltF of R. sphaeroides is involved in the recognition of the rod chaperone FlgJ. We also found that in many alphaproteobacteria, the flagellar cluster includes a homolog of SltF and FlgJ, indicating that association of an LT with the flagellar machinery is ancestral. A maximum likelihood tree shows that family 1 of LTs segregates into seven subfamilies.

KEYWORDS: Rhodobacter sphaeroides, lytic transglycosylase, bacterial flagellum

ABSTRACT

In this work, we have characterized the soluble lytic transglycosylase (SltF) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides that interacts with the scaffolding protein FlgJ in the periplasm to open space at the cell wall peptidoglycan heteropolymer for the emerging rod. The characterization of the genetic context of flgJ and sltF in alphaproteobacteria shows that these two separate genes coexist frequently in a flagellar gene cluster. Two domains of unknown function in SltF were studied, and the results show that the deletion of a 17-amino-acid segment near the N terminus does not show a recognizable phenotype, whereas the deletion of 47 and 95 amino acids of the C terminus of SltF disrupts the interaction with FlgJ without affecting the transglycosylase catalytic activity of SltF. These mutant proteins are unable to support swimming, indicating that the physical interaction between SltF and FlgJ is central for flagellar formation. In a maximum likelihood tree of representative lytic transglycosylases, all of the flagellar SltF proteins cluster in subfamily 1F. From this analysis, it was also revealed that the lytic transglycosylases related to the type III secretion systems present in pathogens cluster with the closely related flagellar transglycosylases.

IMPORTANCE Flagellar biogenesis is a highly orchestrated event where the flagellar structure spans the bacterial cell envelope. The rod diameter of approximately 4 nm is larger than the estimated pore size of the peptidoglycan layer; hence, its insertion requires the localized and controlled lysis of the cell wall. We found that a 47-residue domain of the C terminus of the lytic transglycosylase (LT) SltF of R. sphaeroides is involved in the recognition of the rod chaperone FlgJ. We also found that in many alphaproteobacteria, the flagellar cluster includes a homolog of SltF and FlgJ, indicating that association of an LT with the flagellar machinery is ancestral. A maximum likelihood tree shows that family 1 of LTs segregates into seven subfamilies.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial flagellum is a molecular ion-driven rotating motor that has given bacteria an evolutionary edge allowing microorganisms to colonize many environments. This complex multimeric structure extends from the cytoplasm to the external medium and can be divided into three main substructures, the basal body, the hook, and the filament. The biogenesis of this organelle is tightly regulated; hence, the process requires the hierarchical expression of more than 50 genes (1, 2). A bell-shaped structure called the C-ring or switch houses the type III export machinery that translocates unfolded structural subunits through a narrow 2-nm channel (3). Flagellar assembly proceeds outwardly in an orchestrated manner from proximal to distal structures. The basal body comprises a rod and a series of rings, the membrane supramembrane (MS) ring and in Gram-negative bacteria, two more rings designated L (lipopolysaccharide) and P (peptidoglycan), which act possibly as bushings for the rotating structure and allow the rod to penetrate the cell envelope (4). Attached to the rod is the hook, a flexible universal joint that connects with a long rigid filament constructed from flagellin subunits 15 to 20 μm from the cell surface (5, 6).

The peptidoglycan (PG) layer must be penetrated at a certain point in the assembly process by the rod, which is believed to be thicker (11 nm) (7) than the peptidoglycan mesh diameter (ca. 4 to 8 nm) (8). This heteropolymer mesh surrounds the bacterial cell to confer support, shape, and resistance to internal pressure (9, 10). It is constantly remodeled and reinforced to allow bacterial growth and insertion of the bacterial flagellum. The peptidoglycan layer is a physical barrier for the assembly of structures that are larger than its pores (11, 12). Nevertheless, peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes are not an absolute requirement for flagellar assembly, given that the growth of the structure may proceed by taking advantage of gaps that are created during normal metabolism by peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes (13). In the cases where dedicated muramidase enzymes participate in transenvelope structure assembly, their activities are likely to be under spatial and temporal control. Most of these systems have evolved enzymes called lytic transglycosylases, a class of autolysins that rearrange the cell wall (11, 14, 15). In many bacteria, the assembly of the flagellum includes a specialized protein, FlgJ, that has dual functions as a scaffold for rod assembly and glucosaminidase-degrading activity to facilitate rod penetration (16, 17). This dual function of FlgJ has been reported only in betaproteobacteria and gammaproteobacteria (18). We have reported previously that FlgJ from the alphaproteobacterium R. sphaeroides lacks the muramidase domain and that it acts only as a scaffolding rod-capping protein (19). The flagellum-specific soluble lytic transglycosylase (SltF) in R. sphaeroides is encoded within the flgG operon, and it is exported to the periplasm via the SecA pathway, where it interacts with FlgJ to open a gap in the PG layer (20). SltF has a long C terminus of 95 residues that extends beyond the catalytic domain. The deletion of the last 48 residues does not affect enzymatic activity, but the mutant protein does not support swimming. In addition, the absence of this region hinders the ability of SltF to interact with itself, whereas the capacity to interact with FlgJ is increased, indicating that the C-terminal region of SltF is involved in the regulation of a transient interaction with FlgJ (21).

In this study, we have explored the C-terminal region of SltF that is contiguous to the catalytic domain, and we demonstrate that a region 47 residues long is devoted to the recognition of FlgJ. Also, a bioinformatic search and phylogenetic analysis show that dedicated LTs cluster to form two subfamilies, 1F and 1G.

RESULTS

The C-terminal region of SltF in different bacterial species is variable.

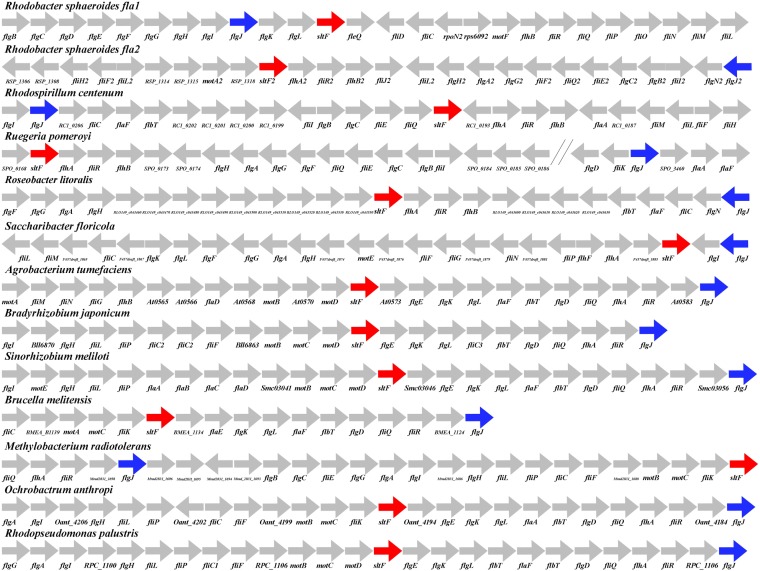

In contrast to the situation observed for the bidomain FlgJ protein of enteric bacteria, in R. sphaeroides, rod formation requires the action of two single-domain proteins, i.e., FlgJ and SltF. FlgJ has only the rod-scaffolding domain, while SltF is the lytic transglycosylase dedicated for rod formation (19, 20). To determine if the genes encoding the single-domain SltF proteins are broadly distributed, we searched for ortholog genes in other bacterial species and carried out an exhaustive search in all the available bacterial genomes present in the IMG database (see Materials and Methods). From this analysis, we found 46 genomes with single-domain sltF genes in different alphaproteobacteria. Figure 1 shows 13 representative examples of this large set of alphaproteobacteria (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). It can be observed that these genes are always found in a flagellar context. Furthermore, in the case of R. sphaeroides, which contains two complete flagellar gene systems, sltF and flgJ exist as separate entities, regardless of the different phylogenetic origins of these two flagellar gene sets (22). It should be noted that this specific domain architecture was found only in alphaproteobacteria.

FIG 1.

Flagellar context of lytic transglycosylases. The flagellar context for lytic transglycosylases and single-domain scaffolding flgJ genes. LTs are as follows: SltFRs, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651573991); SltF2Rs, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651575303); SltFRc, Rhodospirillum centenum (643411101); SltFSp, Ruegeria pomeroyi (637287661); SltFRl, Roseobacter litoralis (2510237871); SltFSf, Saccharibacter floricola (2519014188); SltFAgt, Agrobacterium tumefaciens (639296061) SltFBj, Bradyrhizobium japonicum (637374448); SltFBm, Brucella melitensis (643747691); SltFBsp, Bradyrhizobium sp. (2514088350); SltFSm, Sinorhizobium meliloti (637181464); SltFRp, Rhodopseudomonas palustris (637924221); SltFMr, Methylobacterium radiotolerans (641627382); and SltFOa, Ochrobactrum anthropi (640836883). Red arrows indicate the lytic transglycosylase genes, and blue arrows indicate the scaffolding flgJ genes. The accession numbers for each sequence (in parentheses) are in accordance with Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG; https://img.jgi.doe.gov/) or with GenBank. The genetic representations are not according to scale.

Given that the transglycosylase has to reach the cell wall, we searched for the existence of a signal peptide sequence in order to support the idea that these genes are functional (see Table S1) (23). As expected, the majority of the SltF proteins pose a signal sequence as occurs in R. sphaeroides (SltFRs).

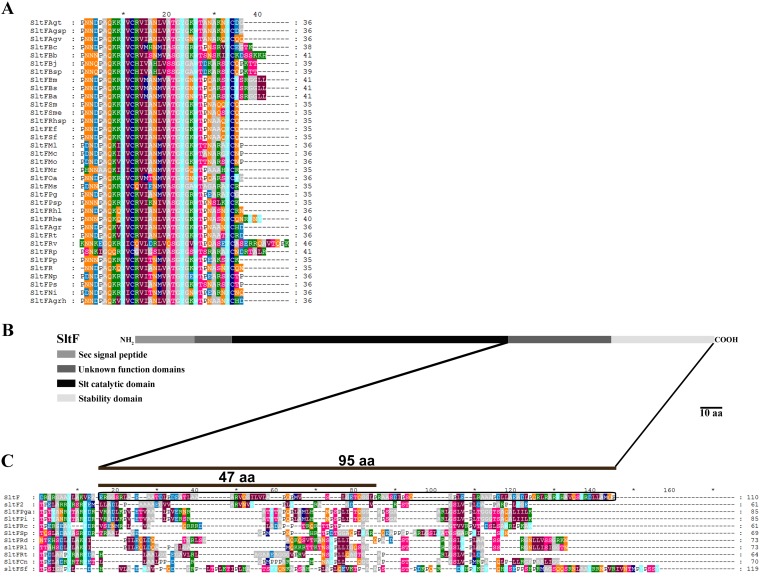

The C termini of SltF of the 46 species of alphaproteobacteria were aligned, and we found that the majority of these sequences show a short conserved C terminus (Fig. 2A) and that a limited number of these show long, less-well-conserved C termini (Fig. 2C). The C-terminal region of SltFRs belongs in this group and shows a 95-amino-acid (aa) region that has been partially studied (Fig. 2B and C) (21).

FIG 2.

C-terminal alignment flagellar lytic transglycosylases. (A) Lytic transglycosylases with a short C terminus are as follows: SltFBs, Brucella suis (637332230); SltFBa, Brucella abortus (637647151); SltFBm, Brucella melitensis (643747691); SltFOa, Ochrobactrum anthropi (640836883); SltFPp, Pannonibacter phragmitetus (2521738048); SltFPg, gilvum (2512365150); SltFRv, Rhodomicrobium vannielii (649746019); SltFMs, Methylocella silvestris (643463373); SltFPsp, Pseudovibrio sp. (2511538202); SltFMr, Methylobacterium radiotolerans (641627382); SltFBsp, Bradyrhizobium sp. (2514088350); SltFBj, Bradyrhizobium japonicum (637374448); SltFRp, Rhodopseudomonas palustris (637924221); SltFBb, Bartonella bacilliformis (639842294); SltFBc, Bartonella clarridgeiae (2548760840); SltFMo, Mesorhizobium opportunistum (2503200023); SltFMl, Mesorhizobium loti (637075604); SltFMc, Mesorhizobium ciceri (649871818); SltFPs, Pseudaminobacter salicylatoxidans (2551926637); SltFNi, Nitratireductor indicus (2520373292); SltFNp, Nitratireductor pacificus (2520250528); SltFAgrh, Agrobacterium rhizogenes (2505292958); SltFAgr, Agrobacterium radiobacter (643645133); SltFRt, Rhizobium tropici (2524419140); SltFRhe, Rhizobium etli (640437712); SltFR, Rhizobium phaseoli (2549960670); SltFRhl, Rhizobium leguminosarum (2510372010); SltFAgv, Agrobacterium vitis (643650334); SltFAgsp, Agrobacterium sp. (650739020); SltFAgt, Agrobacterium tumefaciens (639296061); SltFRhsp, Rhizobium sp.(643824500); SltFSf, Sinorhizobium fredii (2517638777); SltFEf, Ensifer fredii (2515008689); SltFSm, Sinorhizobium meliloti (637181464); and SltFSme, Sinorhizobium medicae (640789209). (B) Scheme of SltF to emphasize the regions in the protein, as well as the 95-residue segment that was studied. (C) Lytic transglycosylases with a long C terminus. In a black frame are shown the last 95 residues of SltF1 from R. sphaeroides studied in this work. LTs shown are as follows: SltFPi, Phaeobacter inhibens (2574253765); SltFPga, Phaeobacter gallaeciensis (2558539010); SltFSp, Ruegeria pomeroyi (637287661); SltFRt, Rubellimicrobium thermophilum (2521341176); SltF2, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651575303); SltFCn, Catellibacterium nectariphilum (2525538211); SltFRl, Roseobacter litoralis (2510237871); SltFRd, Roseobacter denitrificans (639633682); SltFSf, Saccharibacter floricola (2519014188); SltFRc, Rhodospirillum centenum (643411101); and SltF, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651573991). The accession numbers for each sequence (in parentheses) are in accordance with Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG; https://img.jgi.doe.gov/) or with GenBank.

A region of the C terminus of SltFRs is required for swimming but not for enzymatic activity.

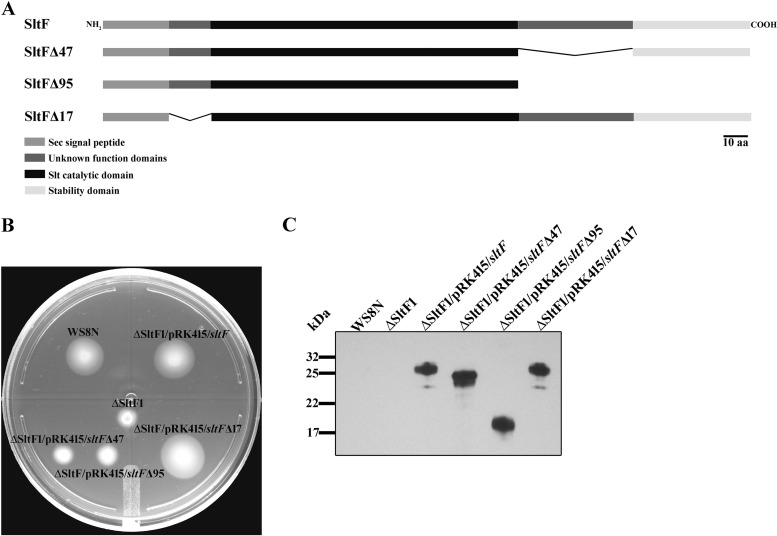

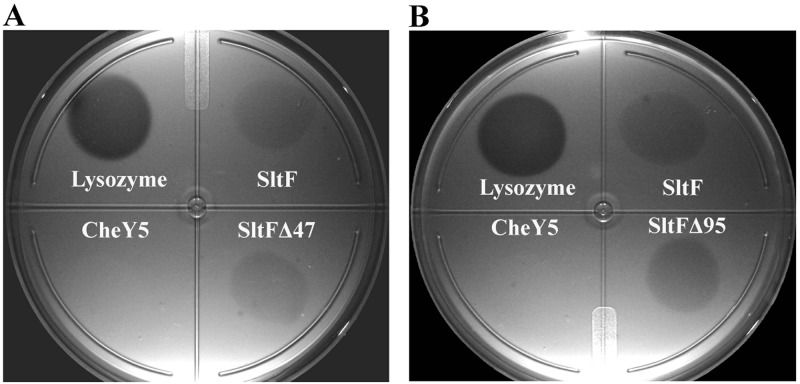

We analyzed a 47-amino-acid residue stretch located at the beginning of the C-terminal domain of SltFRs. Figure 3A shows a schematic representation of SltF and two mutants carrying different deletions of this region. In addition, we analyzed the N-terminal region in the mutant that expresses the protein SltFΔ17 in order to evaluate the relevance of a stretch of 17 residues, which shows a low degree of conservation (Fig. 3A and S2). The functionality of these proteins to support swimming was analyzed on soft agar plates (Fig. 3B). As a control, we include WS8N, the strain that expresses the wild-type version of SltF. The mutations affecting the C-terminal region of SltF were impaired in swimming. On the contrary, in the mutant expressing SltFΔ17, swimming is not affected (Fig. 3B). The presence of the three mutant SltF proteins (SltFΔ17, SltFΔ47, and SltFΔ95) was detected in whole-cell extracts using a polyclonal anti-SltF antibody (Fig. 3C). The two mutant proteins SltFΔ47 and SltFΔ95 were tested for their ability to carry out transglycosylase activity on lysoplates. Figure 4 shows that SltFΔ47 and SltFΔ95 (panels A and B, respectively) are active compared to the wild-type SltF. From these results, we conclude that the two C-terminal deletions do not affect the catalytic activity of SltF.

FIG 3.

SltF mutants. (A) Schematic representation of the various constructs of SltF of R. sphaeroides. (B) Swimming plates for motility assays, with 0.25% soft agar. Shown are wild-type WS8N, SltF1 (ΔsltF mutant), and SltF1/SltF (SltF1 complemented with wild-type sltF) strains, as well as strains of the SltF1 mutant complemented with sltFΔ47, sltFΔ95, and sltFΔ17. (C) Western blot (15% SDS-PAGE gels) analysis of the different sltF versions that were used in this work. Anti-SltF gamma globulins were used for these assays.

FIG 4.

Muramidase enzymatic activity. Lyophilized Micrococcus lysodeikticus was mixed with 1% agarose. Plates were spotted with 0.5 μg of lysozyme or 15 μg of SltF, CheY5 as a negative control, and SltFΔ47 (A) or SltFΔ95 (B). All samples were added in a final volume of 100 μl. Petri dishes were incubated at 30°C for 18 h.

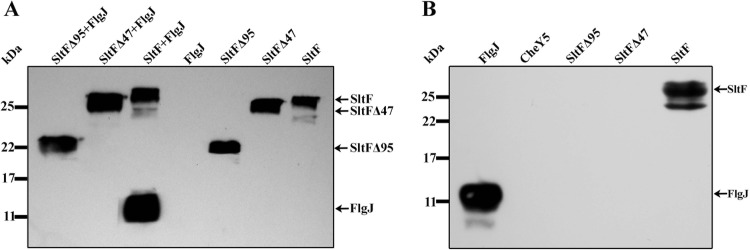

SltFΔ47 and SltFΔ95 mutants are unable to interact with FlgJ.

A relevant question to understand why the mutant versions of SltF do not support swimming was if the ability of these two mutants to interact with the scaffolding protein FlgJ was impaired. Figure 5A shows a pulldown assay where only wild-type SltF interacts with FlgJ, while the two C-terminal mutants (SltFΔ47 and SltFΔ95) lose the ability to interact with the scaffolding protein FlgJ. This result was further confirmed by far-Western blotting. Figure 5B shows that the two mutants are unable to recognize FlgJ that was incubated with the blotted proteins. Also shown is the negative control with the chemotactic protein CheY5. These results point to the importance of the C terminus of SltF to direct the enzyme to the cell wall by FlgJ in order to remodel the peptidoglycan layer at a specific site during flagellar biogenesis.

FIG 5.

FlgJ-SltF interactions. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of wild type SltF and the two mutant versions of SltFΔ95 and SltFΔ47 in the presence or absence of FlgJ. The proteins were used at a concentration of 0.14 μM, and anti-His polyclonal antibodies were used to detect the proteins. (B) Far-Western blot assay with 17.5% SDS-PAGE gels was carried out with the wild type (SltF) and mutants (SltFΔ95 and SltFΔ47). Proteins were loaded at a concentration of 10 nM, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with FlgJ at a concentration of 17 μg/ml. Anti-FlgJ antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution.

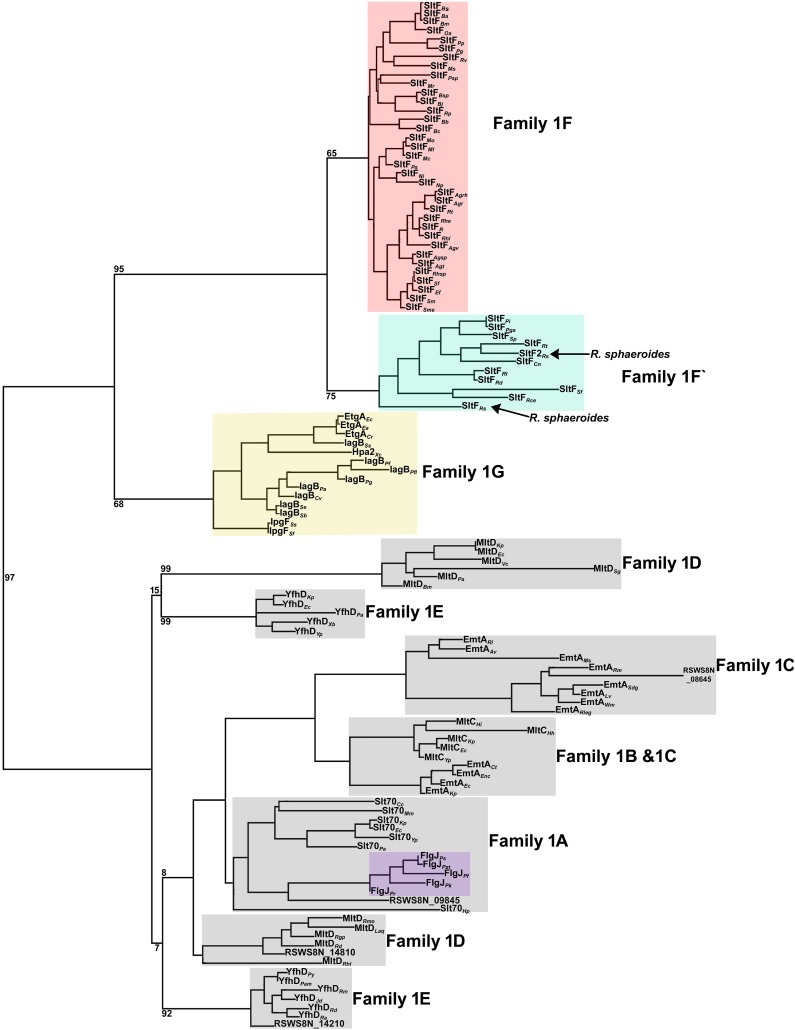

SltF is part of a subgroup of subfamily 1F of the lytic transglycosylases.

We were interested in understanding the phylogenetic relationship of the catalytic domain of the flagellar transglycosylases identified in this study with regard to other LTs. To address this, a maximum likelihood tree was generated using amino acid sequences of the catalytic domain of different LTs of family 1 (A to E) from alpha- and gammaproteobacteria (24), the 46 single-domain LTs (Fig. S1), 5 sequences that show a rod-scaffolding domain fused to SltF (Pfam10135-Pfam01464), and transglycosylases from gammaproteobacteria related to the type III secretion systems, like EtgA from E. coli (25, 26).

This analysis shows that the LTs cluster into 7 subfamilies that were previously reported (24) (Fig. 6). Subfamily 1F includes all the flagellar LTs (27–29). This subfamily clearly segregates into two classes. A recently proposed monophyletic group related to the flagellar transglycosylases is also shown. This subfamily comprises the LTs of the type III secretion systems related to pathogenesis (29). An unforeseen result was that FlgJ fused to SltF of the genus Pseudomonas groups with subfamily 1A of the LTs. As expected for paralogous genes, our results show that the LTs cluster according to the family to which they belong and not according to genus.

FIG 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of the transglycosylases from family 1 (A to E), from the flagellar system, and those involved in the assembly of the injectisome. Transglycosylases from family 1A were as follows: Slt70Cc, Caulobacter crescentus (637087234); Slt70Mm, Magnetospirillum magneticum (637823010); Slt70Kp, Klebsiella pneumoniae (2553879287); Slt70Ec, Escherichia coli (646316385); Slt70Yp, Yersinia pestis (2511786758); Slt70Pa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2511858253); Slt70Hp, Helicobacter pylori (2523150958); and RSWS8N_09845, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651574854). Transglycosylases from family 1B were as follows: MltCHi, Haemophilus influenzae (649866435); MltCHh, Helicobacter hepaticus (637432879); MltCKp, Klebsiella pneumoniae (2553881628); MltCEc, Escherichia coli (646314929); and MltCYp, Yersinia pestis (2511786247). Transglycosylases from family 1C were as follows: EmtARl, Rhizobium leguminosarum (GenBank accession no. ANP86455.1); EmtAAv, Agrobacterium vitis (643651919); EmtAMs, Methylocella silvestris (643463844); EmtARm, Rubellimicrobium mesophilum (2523872517); RSWS8N_08645, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651574612); EmtASdg, Sulfitobacter donghicola (2576119082); EmtALv, Loktanella vestfoldensis (2521728122); EmtAWm, Wenxinia marina (2516026744); EmtARleg, Rhizobium leguminosarum (GenBank accession no. ANP86450.1); EmtACt, Cronobacter turicensis (646330307); EmtAEnc, Enterobacter ludwigii (2636620685); EmtAEc, Escherichia coli (646313111); and EmtAKp Klebsiella pneumoniae (2553879929). Transglycosylases from family 1D were as follows: MltDKp, Klebsiella pneumoniae (2553883339); MltDEc, Escherichia coli (646312109); MltDVc, Vibrio cholerae (2645941335); MltDSg, Saprospira grandis (2512710094); MltDPa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (637052211); MltDBm, Burkholderia multivorans (2538711695); MltDRmo, Ruegeria mobilis (2536817545); MltDLaq, Leisingera aquimarina (2521637605); MltDRgp, Ruegeria pomeroyi (637290549); MltDRd, Roseobacter denitrificans (639635542); RSWS8N_14810 Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651575861); MltDRhl, and Rhizobium leguminosarum (GenBank accession no. ANP91526.1). Transglycosylases from family 1E were as follows: YfhDKp, Klebsiella pneumoniae (2721429630); YfhDEc, Escherichia coli (646314525); YfhDPa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2723169271); YfhDXb, Xenorhabdus bovienii (646634251); YfhDYp, Yersinia pestis (2511788587); YfhDPy, Paracoccus yeei (2558687338); YfhDPam, Paracoccus aminovorans (2616623596); YfhDRm, Ruegeria mobilis (2504812356); YfhDJd, Jannaschia donghaensis (2672243609); YfhDRd, Roseobacter denitrificans (2694921809); YfhDRa, Roseivivax atlanticus (2578592277); and RSWS8N_14210, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651575740). Fused flagellar LTs were as follows: FlgJPs, Pseudomonas stutzeri 19SMN4 (2574576787); FlgJPst, Pseudomonas stutzeri DSM 4166 (651174071); FlgJPf, Pseudomonas fulva 12-X (2506005703); FlgJPk, Pseudomonas knackmussii (2581254789); and FlgJPr, Pseudomonas resinovorans (2562417130). Flagellar LT family 1F was as follows: SltFBs, Brucella suis (637332230); SltFBa, Brucella abortus (637647151); SltFBm, Brucella melitensis (643747691); SltFOa, Ochrobactrum anthropi (640836883); SltFPp, Pannonibacter phragmitetus (2521738048); SltFPg, Polymorphum gilvum (2512365150); SltFRv, Rhodomicrobium vannielii (649746019); SltFMs, Methylocella silvestris (643463373); SltFPsp, Pseudovibrio sp. (2511538202); SltFMr, Methylobacterium radiotolerans (641627382); SltFBsp, Bradyrhizobium sp. (2514088350); SltFBj, Bradyrhizobium japonicum (637374448); SltFRp, Rhodopseudomonas palustris (637924221); SltFBb, Bartonella bacilliformis (639842294); SltFBc, Bartonella clarridgeiae (2548760840); SltFMo, Mesorhizobium opportunistum (2503200023); SltFMl, Mesorhizobium loti (637075604); SltFMc, Mesorhizobium ciceri (649871818); SltFPs, Pseudaminobacter salicylatoxidans (2551926637); SltFNi, Nitratireductor indicus (2520373292); SltFNp, Nitratireductor pacificus (2520250528); SltFAgrh, Agrobacterium rhizogenes (2505292958); SltFAgr, Agrobacterium radiobacter (643645133); SltFRt, Rhizobium tropici (2524419140); SltFRhe, Rhizobium etli (640437712); SltFR, Rhizobium phaseoli (2549960670); SltFRhl, Rhizobium leguminosarum (2510372010); SltFAgv, Agrobacterium vitis (643650334); SltFAgsp, Agrobacterium sp. (650739020); SltFAgt, Agrobacterium tumefaciens (639296061); SltFRhsp, Rhizobium sp. (643824500); SltFSf, Sinorhizobium fredii (2517638777); SltFEf, Ensifer fredii (2515008689); SltFSm, Sinorhizobium meliloti (637181464); and SltFSme, Sinorhizobium medicae (640789209). Flagellar SltF family F′ was as follows: SltFPi, Phaeobacter inhibens (2574253765); SltFPga, Phaeobacter gallaeciensis (2558539010); SltFSp, Ruegeria pomeroyi (637287661); SltFRt, Rubellimicrobium thermophilum (2521341176); SltF2Rs, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651575303); SltFCn, Catellibacterium nectariphilum (2525538211); SltFRl, Roseobacter litoralis (2510237871); SltFRd, Roseobacter denitrificans (639633682); SltFSf, Saccharibacter floricola (2519014188); SltFRce, Rhodospirillum centenum (643411101); and SltFRs, Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8N (651573991). The type III secretion LTs for the injectisome were as follows: EtgAEc, Escherichia coli O127 (643445325); EtgAEa, Escherichia albertii (2548082972); EtgACr, Citrobacter rodentium (646475235); IagBSs, Salmonella enterica salamae (2565098817); Hpa2Xc, Xanthomonas campestris (2555124161); IagPf, Pseudomonas fuscovaginae (2554841929); IagPfl, Pseudomonas fluorescens (2668339600); IagPg, Pseudomonas gingeri (2563875407); IagPa, Providencia alcalifaciens (2565746689); IagBCv, Chromobacterium violaceum (637453449); IagBSe, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (650491333); IagBSb, Salmonella bongori (651033361); IpgFSs, Shigella sonnei (640432293); and IpgFSf, Shigella flexneri (637430878). The accession numbers for each sequence (in parentheses) are in accordance with Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG; https://img.jgi.doe.gov/) or with GenBank.

DISCUSSION

R. sphaeroides possesses a single-domain flagellar FlgJ scaffolding protein that interacts with the lytic transglycosylase SltF to open space at the peptidoglycan membrane for the passage of the flagellar rod (20). It has been previously reported that other bacteria also possess single-domain FlgJ proteins (18). This is in contrast with FlgJ from Salmonella enterica that contains the scaffolding and glucosaminidase domains fused into a single polypeptide (16, 17, 30). In this work, we found that other bacteria also possess LTs encoded by genes that were found in a flagellar context, as occurs in the case of R. sphaeroides. We suggest that these are genes that code for enzymes that carry out the specific degradation of the peptidoglycan layer. We therefore propose naming these sltF genes. The bioinformatic search showed that single-domain SltF proteins were found only in alphaproteobacteria. Interestingly, in Burkholderia thailandensis, the single-domain flgJ is located in a flagellar genetic context, and a glucosaminidase gene was found instead of a lytic transglycosylase (IMG geneID 637837488) (data not shown). R. sphaeroides possesses two flagellar systems, Fla1, which was acquired by horizontal transfer from an ancient gammaproteobacterium, and Fla2, which was vertically inherited. Nevertheless, both flagellar systems possess genes that code for single-domain FlgJ and SltF proteins. This is contrary to what happens with gammaproteobacteria that possess a bifunctional flgJ gene. It suggests that sltF could have originated from a duplication event of sltF2 or of other endogenous genes coding for an LT, followed by positive selection to specialize in a dedicated LT of the Fla1 system (18, 22). Also worth mentioning is that we know that SltF is exported to the periplasm through the Sec system (21). There are SltF proteins that do not show a Sec export signal; therefore, they are possibly exported through a different and still unknown mechanism, or alternatively, the genes were annotated incorrectly.

SltFRs has a long C terminus of 95 amino acids, and in this work, we identified a region of 47 residues that interacts with FlgJ. This region is responsible for the interaction with FlgJ that directs SltF to the precise site where the peptidoglycan layer needs a gap for the nascent filament. The analysis of the long nonconserved C termini of the SltF proteins does not reveal a characteristic signature for the interaction with FlgJ. Therefore, recognition could be achieved through a structural motif that is displayed by the protein. It would be interesting to carry out the characterization of the long nonconserved C termini of other alphaproteobacteria that we have identified in order to gain insight into the role that this region plays in FlgJ recognition.

The transglycosylase domain found in various multidomain proteins (glycosylases), like Slt70 (29, 31), shows that these enzymes have evolved and specialized for different functions (15). We carried out a thorough phylogenetic analysis exclusively with the transglycosylase domain of a large number of bacterial flagellar LTs. It was determined that these flagellar enzymes conform to a distinct phylogenetic group, previously named subfamily 1F (24). Our results show that family 1F is further divided in two subfamilies, i.e., 1F and 1F′, where 1F′ comprises the LTs with a long C terminus. It should be noticed that this subdivision is also observed in a phylogenetic analysis performed with the 16S ribosomal subunit (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). It has been proposed that subfamily 1F can be further subdivided based on whether an S or T residue follows the catalytic E residue (27). However, we observed that most of the enzymes in the 1F subfamily have an invariant T after the catalytic residue (see Fig. S3), and in the enzymes from the 1F′ subfamily, where SltFRs is grouped, the residue immediately after the catalytic E is either T or S. Therefore, this residue is probably not diagnostic of a particular subfamily of LTs.

Closely related to subfamily 1F is subfamily 1G, which includes enzymes involved with the type III secretion systems, among which is EtgA, a transglycosylase involved in the biogenesis of the injectisome (25). This strongly suggests a possible common origin of the two types of LTs.

Another finding is that for the various FlgJ proteins that are fused to flagellar LTs from Pseudomonas, these proteins group with subfamily 1A, which is not involved in flagellar biogenesis.

It is possible that the fusion between the scaffolding and enzymatic domain occurred randomly with any cell wall remodeling glycosylase. Nambu et al. (18) found that the rod-scaffolding domain is fused to various types of cell wall-degrading enzymes (18, 32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and oligonucleotides.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this work are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this work

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Relevant characteristics or sequence (5′–3′)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| JM103 | hsdR4 Δ(lac-pro) F′ traD36 proAB lacIq lacZΔM15 | 34 |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3)/pLysS Cmr | Novagen |

| M15/pREP4 | thi lac gal mlt F′/pREP4 Kanr | Qiagen |

| S17-1 | recA endA thi hsdR RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Kan::Tn7 Tpr Smr | 35 |

| R. sphaeroides | ||

| WS8N | Wild type; spontaneous Nalr | 45 |

| sltF1 | WS8N derivative ΔsltF(1–336)::aadA Fla− Spcr Nalr | 20 |

| sltFΔ47 | WS8N derivative ΔsltF/pRK415 ΔsltF(510–651) Spcr Nalr Tcr | This study |

| sltFΔ95 | WS8N derivative ΔsltF/pRK415 ΔsltF(510–795) Spcr Nalr Tcr | This study |

| sltFΔ17 | WS8N derivative ΔsltF/pRK415 ΔsltF(27–78) Spcr Nalr Tcr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGT001 | 1.4-kb PstI fragment containing sltF wild type cloned into pTZ19R; Ampr | 19 |

| pQE60 | Expression vector; 6×His C-terminal Ampr | Qiagen |

| pQE30 | Expression vector; 6×His N-terminal Ampr | Qiagen |

| pRK415 | pRK404 derivative, for expression on R. sphaeroides, lacZ mob+ Tcr | 46 |

| pRK415/SltF | sltF wild type cloned into EcoRI/HindIII sites of pRK415; Tcr | 20 |

| pRK415/SltFΔ47 | ΔsltF(510–651) cloned into EcoRI/HindIII sites of pRK415; Tcr | This study |

| pRK415/SltFΔ95 | ΔsltF(510–795) cloned into EcoRI/HindIII sites of pRK415; Tcr | This study |

| pRK415/SltFΔ17 | ΔsltF(27–78) cloned into EcoRI/HindIII sites of pRK415; Tcr | This study |

| pQE30/SltF Sec- | sltF cloned into SacI/HindIII sites of pQE30; Ampr | 20 |

| pQE30/SltFΔ95Sec- | ΔsltF(510–795) cloned into SacI/HindIII sites of pQE30; Ampr | This study |

| pQE30/SltFΔ47Sec- | ΔsltF(510–651) cloned into SacI/HindIII sites of pQE30; Ampr | This study |

| pRSJ | flgJ cloned into NcoI/BglII sites of pQE60; Ampr | 20 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Mur/sec/NH2 | CATGGAGCTCGCGGACGAGGGCTGCGAGACG | 20 |

| Mur/sec/COH2 | CCCGAAGCTTTCACGGTTGCATTGCGAGCAG | 20 |

| MurNH2pQE60 | CATGCCATGGCGGACGAGGGCTGCGAGACG | 20 |

| FwΔ17 | CCCCGCCCTCGCGGCGGACGAGGGGCTGATGGAGGCGAT | This study |

| RvΔ17 | ATCGCCTCCATCAGCCCCTCGTCCGCCGCGAGGGCGGGGG | This study |

| FwΔ47 | TCGCCAAGGTCGAGGCCGAGGCGGCCTCCGACATTCCCTC | This study |

| RvΔ47 | GAGGGAATGTCGGAGGCCGCCTCGGCCTCGACCTTGGCGA | This study |

| FwΔ95(1558) | CTTTCGATGCCGCCGTGAGC | This study |

| RvΔ95 | CCCGAAGCTTTCACTCGGCCTCGACCTTGGCC | This study |

| RvΔ95His | CCTGAGATCTCTCGGCCTCGACCTTGGC | This study |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Tpr, trimethoprim resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Spcr, spectinomycin resistance; Nalr, nalidixic acid resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance.

Media, growth conditions, and molecular biology techniques.

Sistrom's culture medium (33) was used to grow R. sphaeroides WS8N at 30°C under constant illumination in completely filled static screw-cap tubes. When required, the following antibiotics were added at the indicated concentrations: nalidixic acid, 20 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 1 μg/ml. Strains of Escherichia coli were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C (34). When needed, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml; tetracycline, 25 μg/ml; ampicillin, 200 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml. Standard molecular biology techniques were used for isolation and purification of chromosomal DNA from R. sphaeroides WS8N. Plasmid DNA and PCR fragments were purified with QIAprep Spin and QIAquick PCR kits, respectively (Qiagen GmbH, Germany). The products were cloned either in pTZ19R or pTZ18R, as required. DNA sequencing was carried out in an ABI Prism automatic sequencer. PCRs (PCR F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Basel, Switzerland) were carried out using PfuTurbo (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and the oligonucleotides synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cloning, site-directed mutagenesis, and complementation assays.

The mutants used in this study were obtained using the following oligonucleotides: FwΔ47, RvΔ47, FwΔ17, and RvΔ17. Mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChange method (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with plasmid pGT001 as the template. For the SltFΔ95 mutant, a PCR was carried out using the oligonucleotides FwΔ95 and RvΔ95, and plasmid pGT001 was used as the template. The PCR products of sltF were cloned in the overexpression vector pQE30 or in pRK415 using the oligonucleotides Mur/sec/NH2, Mur/sec/COH2, and RvΔ95His, and the appropriate restriction sites for each vector. The ΔsltF mutant of R. sphaeroides WS8N was complemented with various mutant versions of sltF that were cloned in pRK415 (Table 1). Each mutant was introduced by conjugation using the E. coli strain S17-1. The presence of SltF was verified by Western blot analysis, using anti-SltF polyclonal antiserum at a 1:2,500 dilution. Detection of bands was performed by using the Thermo SuperSignal detection kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Conjugation.

Cultures of E. coli and R. sphaeroides of 2 and 10 ml, respectively, were grown overnight with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. For E. coli, 50 μl of the overnight culture was inoculated into 5 ml of LB broth, and growth continued until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 was reached. For R. sphaeroides, 100 μl of the overnight culture was inoculated into 10 ml of Sistrom's medium, and growth was continued until an OD600 of 0.5 was reached. Cultures were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min, and the pellets were resuspended in 0.5 ml of LB medium. Plasmids were introduced into a ΔsltF mutant strain by diparental conjugation using E. coli strain S17-1, as described previously (35).

Motility assays.

A 2-μl sample of a stationary-phase culture was spotted on the surface of swarm plates (34), followed by aerobic incubation in the dark at 30°C. Swarming ability was recorded as the ability of bacteria to move away from the inoculation point after 24 h of incubation. Soft agar (0.25%) swimming plates were prepared with Sistrom's minimal medium devoid of succinic acid, to which 100 μM sodium propionate was added.

Overexpression and purification of SltF, FlgJ, SltFΔ47, and SltFΔ95.

Overexpression and purification of SltF and FlgJ were carried out as described previously (20). SltFΔ47 and SltFΔ95 were overexpressed and purified as follows, using E. coli strain M15/pREP4. Transformed cells were grown in 12 ml of LB medium overnight at 37°C with orbital shaking. Grown cells were inoculated in 500 ml of LB medium and allowed to grow at 37°C with orbital shaking until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached; 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added and the culture allowed to grow for 4 h at 25°C. Cells were washed and resuspended in 10 ml of a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.6) and sonified with a Branson Sonifier 250 (Danbury, CT) for 1 min at a power of 3 for 5 times, in an ice bath. The sample was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g and 4°C to collect the insoluble fraction, the pellet was resuspended in the same buffer and centrifuged for 1 h at 25,000 × g and 4°C, and the inclusion bodies were washed and resuspended according to the Burgess protocol (36). The supernatant was incubated at 4°C with nickel-Sepharose beads for 16 h and washed several times with 15 mM imidazole; finally, the protein was eluted with 250 mM imidazole. The protein was refolded by dialysis for 16 h at 4°C in a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 6.5) for SltFΔ95 and 50 mM NaH2PO4, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (pH 6.8) for SltFΔ47. Protein content was determined as reported previously (37).

Western blot analysis.

Samples were separated on either 15.0 or 17.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, as required. The proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (38). Polyclonal gamma globulins raised against SltF or FlgJ were produced as described previously (20). Anti-SltF and anti-FlgJ gamma globulins were used at 1:2,500 and 1:1,000 dilutions, respectively.

Immunoprecipitation.

A volume of 20 μl from a 25 mg/ml stock solution Sepharose CL-4B was coupled to protein A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and incubated with 8 μg of anti-SltF gamma globulins in 1 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) for 12 h at 4°C, after which the tube was centrifuged and the supernatant discarded. To evaluate the interaction of SltF, SltFΔ47, and SltFΔ95 with FlgJ, 0.14 μM each protein was incubated for 1 h at 4°C and added to the anti-SltF gamma globulins coupled to protein A-Sepharose. The mixture was incubated 1 h at 4°C and washed 5 times with 1 ml of phosphate buffer. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. The samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and developed using HisProbe-horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Affinity blotting.

SDS-PAGE gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). The membranes were blocked 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline (TTBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20, 150 mM NaCl, and 5% nonfat milk powder. The membranes were incubated with purified FlgJ (17 μg/ml) in TTBS buffer for 1 h. The membrane was probed with anti-FlgJ at a 1:1,000 dilution. Detection was performed by using the SuperSignal detection kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Muramidase activity assay.

Lysoplates were used to determine muramidase activity. Briefly, petri dishes were filled with 1.0% agarose in a buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 6.5) and also containing 0.05% of a cell lysate from Micrococcus lysodeikticus (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) that is used as a substrate for enzymatic activity (39). The lysoplates were spotted with 15 μg of each protein, and lysozyme (0.5 μg) was used as a positive control. The plates were incubated for 18 h at 30°C.

Bioinformatic and phylogenetic analyses.

A total of 2,832 genomes were selected from the Integrated Microbial Genomes database (https://img.jgi.doe.gov) (40). The genomes that contained genes that code for proteins that contain a Pfam10135 domain (41) that defines the N-terminal assembly domain of FlgJ were analyzed, and a total of 1,140 proteins were found. Around half of these polypeptides (599 proteins) also contained the domain that defines the glucosaminidase domain (Pfam01832), 9 proteins contained the peptidase M23 domain (Pfam01551), and 12 proteins contained the transglycosylase domain (Pfam01464). The assembly domain (Pfam10135) was found in 520 proteins. It should be noted that these proteins only contain this domain. We then searched in these 520 genomes for genes that code for transglycosylases with domain Pfam01464. The search was done manually and with the help of Gene Ortholog Neighborhoods (available at https://img.jgi.doe.gov). We found 120 gene sequences that were in a flagellar context and code for proteins with domain Pfam01464. The genomes from species with multiple strains were discarded, leaving only 46 gene sequences that code for proteins with a single transglycosylase domain.

From these 46 sequences, the complete transglycosylase domain (Pfam01464) was removed, and the remaining C-terminal region was aligned using MUSCLE (42); the resulting alignment was edited using the GeneDoc software (https://github.com/karlnicholas/GeneDoc).

The phylogenetic tree was constructed including sequences from the transglycosylases of family 1 (A to E) (24), the 46 single-domain transglycosylases found in a flagellar context, and 5 out of 12 sequences that carry a fusion of the rod-scaffolding domain to the LT domain (Pfam10135-Pfam01464). We also included transglycosylases related to the type III secretion systems, like EtgA from E. coli (25). The alignment was carried out exclusively with the transglycosylase domain of each of these sequences using MUSCLE. The alignment was further refined manually, and the most divergent sequences were eliminated using gBlocks (43). We then carried out a maximum likelihood (ML) tree that was generated using PhyML (44), with the following parameters: substitution model, JTT; bootstrap, 100.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.G.-R. was supported by a fellowship from CONACyT. This work was partially funded by DGAPA-UNAM (grant PAPIIT-IN204317) and CONACyT (grant CB2014-235996).

We thank Aurora Osorio for technical support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00397-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macnab RM. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:77–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge P, Hughes KT. 2002. Regulation of flagellar assembly. Curr Opin Microbiol 5:160–165. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2008. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:455. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevance FF, Takahashi N, Karlinsey JE, Gnerer J, Hirano T, Samudrala R, Aizawa S-I, Hughes KT. 2007. The mechanism of outer membrane penetration by the eubacterial flagellum and implications for spirochete evolution. Genes Dev 21:2326–2335. doi: 10.1101/gad.1571607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samatey FA, Imada K, Nagashima S, Vonderviszt F, Kumasaka T, Yamamoto M, Namba K. 2001. Structure of the bacterial flagellar protofilament and implications for a switch for supercoiling. Nature 410:331. doi: 10.1038/35066504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samatey FA, Matsunami H, Imada K, Nagashima S, Shaikh TR, Thomas DR, Chen JZ, DeRosier DJ, Kitao A, Namba K. 2004. Structure of the bacterial flagellar hook and implication for the molecular universal joint mechanism. Nature 431:1062. doi: 10.1038/nature02997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sosinsky GE, Francis NR, Stallmeyer M, DeRosier DJ. 1992. Substructure of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella Typhimurium. J Mol Biol 223:171–184. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90724-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meroueh SO, Bencze KZ, Hesek D, Lee M, Fisher JF, Stemmler TL, Mobashery S. 2006. Three-dimensional structure of the bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:4404–4409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höltje JV. 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62:181–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vollmer W, Blanot D, de Pedro MA. 2008. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:149–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheurwater EM, Burrows LL. 2011. Maintaining network security: how macromolecular structures cross the peptidoglycan layer. FEMS Microbiol Lett 318:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dijkstra AJ, Keck W. 1996. Peptidoglycan as a barrier to transenvelope transport. J Bacteriol 178:5555–5562. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5555-5562.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S. 2006. Nanomolecular and supramolecular paths toward peptidoglycan structure. Microbe 1:420–427. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koraimann G. 2003. Lytic transglycosylases in macromolecular transport systems of Gram-negative bacteria. Cell Mol Life Sci 60:2371–2388. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zahrl D, Wagner M, Bischof K, Bayer M, Zavecz B, Beranek A, Ruckenstuhl C, Zarfel GE, Koraimann G. 2005. Peptidoglycan degradation by specialized lytic transglycosylases associated with type III and type IV secretion systems. Microbiology 151:3455–3467. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirano T, Minamino T, Macnab RM. 2001. The role in flagellar rod assembly of the N-terminal domain of Salmonella FlgJ, a flagellum-specific muramidase1. J Mol Biol 312:359–369. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herlihey FA, Moynihan PJ, Clarke AJ. 2014. The essential protein for bacterial flagella formation FlgJ functions as β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. J Biol Chem 289:31029–31042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nambu T, Inagaki Y, Kutsukake K. 2006. Plasticity of the domain structure in FlgJ, a bacterial protein involved in flagellar rod formation. Genes Genet Syst 81:381–389. doi: 10.1266/ggs.81.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González-Pedrajo B, de la Mora J, Ballado T, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2002. Characterization of the flgG operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides WS8 and its role in flagellum biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1579:55–63. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(02)00504-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de la Mora J, Ballado T, González-Pedrajo B, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2007. The flagellar muramidase from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 189:7998–8004. doi: 10.1128/JB.01073-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de la Mora J, Osorio-Valeriano M, González-Pedrajo B, Ballado T, Camarena L, Dreyfus G. 2012. The C terminus of the flagellar muramidase SltF modulates the interaction with FlgJ in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 194:4513–4520. doi: 10.1128/JB.00460-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poggio S, Abreu-Goodger C, Fabela S, Osorio A, Dreyfus G, Vinuesa P, Camarena L. 2007. A complete set of flagellar genes acquired by horizontal transfer coexists with the endogenous flagellar system in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol 189:3208–3216. doi: 10.1128/JB.01681-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliver D. 1985. Protein secretion in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Microbiol 39:615–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackburn NT, Clarke AJ. 2001. Identification of four families of peptidoglycan lytic transglycosylases. J Mol Evol 52:78–84. doi: 10.1007/s002390010136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Gómez E, Espinosa N, de la Mora J, Dreyfus G, González-Pedrajo B. 2011. The muramidase EtgA from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is required for efficient type III secretion. Microbiology 157:1145–1160. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.045617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pallen MJ, Beatson SA, Bailey CM. 2005. Bioinformatics analysis of the locus for enterocyte effacement provides novel insights into type-III secretion. BMC Microbiol 5:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herlihey FA, Osorio-Valeriano M, Dreyfus G, Clarke AJ. 2016. Modulation of the lytic activity of the dedicated autolysin for flagellum formation SltF by flagellar rod proteins FlgB and FlgF. J Bacteriol 198:1847–1856. doi: 10.1128/JB.00203-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herlihey FA, Clarke AJ. 2017. Controlling autolysis during flagella insertion in Gram-negative bacteria. Adv Exp Med Biol 925:41–56. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dik DA, Marous DR, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. 2017. Lytic transglycosylases: concinnity in concision of the bacterial cell wall. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 52:503–542. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2017.1337705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nambu T, Minamino T, Macnab RM, Kutsukake K. 1999. Peptidoglycan-hydrolyzing activity of the FlgJ protein, essential for flagellar rod formation in Salmonella Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 181:1555–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thunnissen AM, Dijkstra AJ, Kalk KH, Rozeboom HJ, Engel H, Keck W, Dijkstra BW. 1994. Doughnut-shaped structure of a bacterial muramidase revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature 367:750–753. doi: 10.1038/367750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santin YG, Cascales E. 2017. Domestication of a housekeeping transglycosylase for assembly of a type VI secretion system. EMBO Rep 18:138–149. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sistrom WR. 1962. The kinetics of the synthesis of photopigments in Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. J Gen Microbiol 28:607–616. doi: 10.1099/00221287-28-4-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Struhl K. 1988. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Media, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burgess RR. 2009. Refolding solubilized inclusion body proteins. Methods Enzymol 463:259–282. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harlow E, Lane D. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becktel WJ, Baase WA. 1985. A lysoplate assay for Escherichia coli cell wall-active enzymes. Anal Biochem 150:258–263. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markowitz VM, Chen I-MA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Grechkin Y, Ratner A, Jacob B, Huang J, Williams P, Huntemann M, Anderson I, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Kyrpides NC. 2012. IMG: the Integrated Microbial Genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D115–D122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A. 2016. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castresana J. 2000. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sockett RE, Foster JCA, Armitage JP. 1990. Molecular biology of Rhodobacter sphaeroides flagellum, p 473–479. In Drews G, Dawes EA (ed), Molecular biology of membrane-bound complexes in phototrophic bacteria. Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keen NT, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.