Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) affect an increasing number of individuals worldwide. Infection with these organisms is more common in patients with chronic lung conditions, and treatment is challenging.

KEYWORDS: Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis, Mycobacterium abscessus, biofilm, mouse model, treatment, infection, ciprofloxacin, liposome, lung disease, Mycobacterium avium

ABSTRACT

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) affect an increasing number of individuals worldwide. Infection with these organisms is more common in patients with chronic lung conditions, and treatment is challenging. Quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, have been used to treat patients, but the results have not been encouraging. In this report, we evaluate novel formulations of liposome-encapsulated ciprofloxacin (liposomal ciprofloxacin) in vitro and in vivo. Its efficacy against Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus was examined in macrophages, in biofilms, and in vivo using intranasal instillation mouse models. Liposomal ciprofloxacin was significantly more active than free ciprofloxacin against both pathogens in macrophages and biofilms. When evaluated in vivo, treatment with the liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations was associated with significant decreases in the bacterial loads in the lungs of animals infected with M. avium and M. abscessus. In summary, topical delivery of liposomal ciprofloxacin in the lung at concentrations greater than those achieved in the serum can be effective in the treatment of NTM, and further evaluation is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are increasingly being diagnosed and reported worldwide (1, 2). NTM are known to be associated with disseminated infections in immune-suppressed individuals and with lung infections in patients with underlying lung pathology, such as bronchiectasis, emphysema, and cystic fibrosis (2, 3).

Among the NTM bacteria, the most common organisms are the members of the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) (Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis, Mycobacterium intracellulare) and the Mycobacterium abscessus group (Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus, Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii, and Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. massiliense) (1).

Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis and M. abscessus infect the airways of patients with impairment in the mechanical mechanism of defense, as well as innate immune defense, and can subsequently establish an infectious niche (1, 4). Studies have proposed that because those bacteria are able to form biofilms, infection is difficult for the host immune system to combat (5, 6). In fact, recent observations confirmed the presence of bacterial aggregates and biofilm structures in patients and that these contribute to the inefficiency of the host immune apparatus to fight the infection (7).

More recently, it has been described that biofilms of both M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. abscessus export extracellular DNA (eDNA), which makes them more robust and resistant to both host defense and therapy (8).

Studies have also determined that NTM lung infections in populations at risk can be challenging to treat, with incidence of recurrence with the same or different bacterial strains being very high (9). In the majority of occasions, the recurrent infection or even the reinfection is caused by organisms susceptible to the original therapy (10), although antibiotic-resistant strains of both M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. abscessus have frequently been observed (11).

Ciprofloxacin is a quinolone recommended for the treatment of tuberculosis as well as NTM infections caused by members of the M. avium complex (MAC) in patients with AIDS (12). The antibiotic has activity in vitro against many M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. intracellulare strains and has been used in patients as a component of combination therapy (13). Results of clinical studies, however, have questioned the ability of ciprofloxacin to eliminate both M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. intracellulare infections, as well as M. abscessus infections (14). Based on the knowledge that the MIC of systemic ciprofloxacin against many NTM strains is close to the concentration achievable in tissues and many times above the concentration achieved both with host cells and in biofilms (15), it would be expected that therapy with ciprofloxacin would be associated with limitations as an anti-NTM therapy.

In this study, we report on the activity of liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations compared to the activity of free ciprofloxacin in in vitro models (a macrophage system and biofilms) and an in vivo mouse model employing two different mouse models, one for M. avium subsp. hominissuis infections and the other for M. abscessus infections. The liposomal formulation has several advantages compared to free ciprofloxacin; for example, (i) it provides high sustained concentrations of ciprofloxacin in the lungs and airways from the slow release from the liposomes (16–21); (ii) the macrophages targeted by M. avium and M. abscessus (22) avidly phagocytize both the liposomal ciprofloxacin and the mycobacteria, bringing both into close proximity within the phagosomes and increasing the drug's bioavailability; and (iii) liposome-encapsulated antibiotics are better able to penetrate bacterial biofilms in the lungs (23–25).

Three liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations (Aradigm Corp., Hayward, CA) were tested: a liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI) formulation, Linhaliq (comprised of a combination of liposomally encapsulated ciprofloxacin and free ciprofloxacin), and a liposomal formulation containing ciprofloxacin in a nanocrystalline state. Linhaliq is the most advanced formulation, having successfully completed a phase 2 trial (26) and two phase 3 clinical trials (20) in patients with non-cystic fibrosis (non-CF) bronchiectasis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. CFI has been successfully tested in one phase 2a trial in CF patients with P. aeruginosa infection (17–19). The nanocrystal formulation has not yet been tested clinically (21).

Once daily inhalation of Linhaliq resulted in ciprofloxacin concentrations in the sputum of patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis that were 3 orders of magnitude higher than those achieved with oral and intravenous (i.v.) ciprofloxacin (17, 28) and resulted in significant decreases in the bacterial load in mouse models of both M. avium subsp. hominissuis infection and M. abscessus infection, as demonstrated in this report.

RESULTS

MICs.

The MICs of ciprofloxacin for M. avium subsp. hominissuis strains A5, MAC104, MAC109, and MAC101 were 4, 5, 6, and 5 μg/ml, respectively. The MICs of ciprofloxacin for M. abscessus shows 101, NIH1, NIH2, and S1 were 5, 8, 8, and 8 μg/ml, respectively.

Activity in a macrophage system.

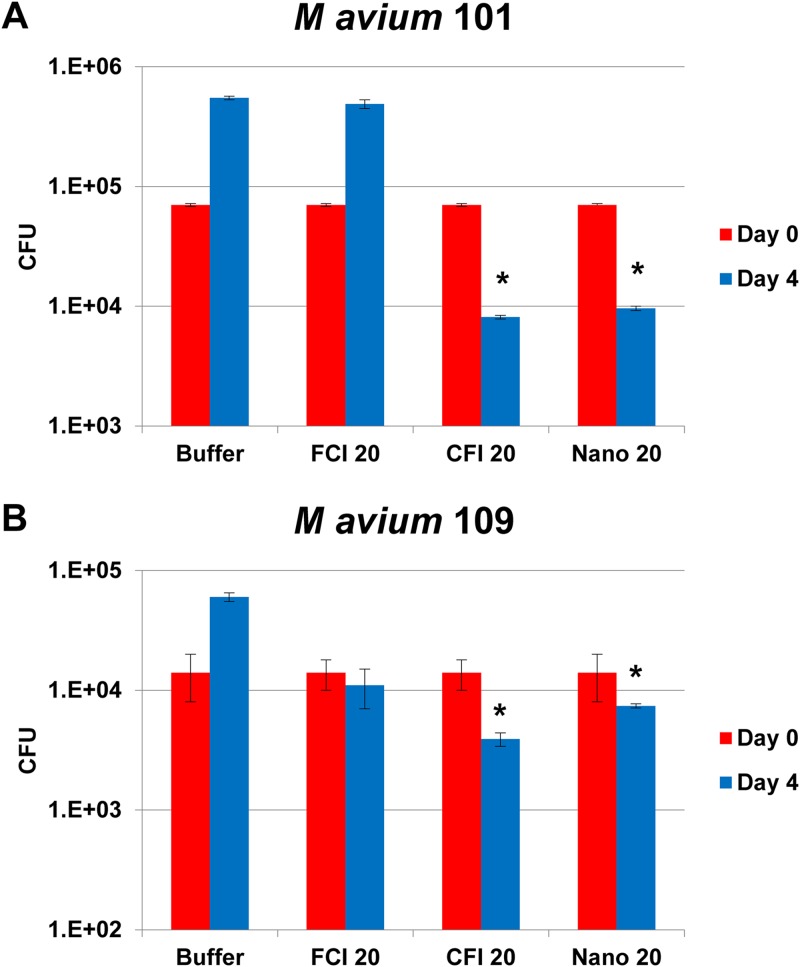

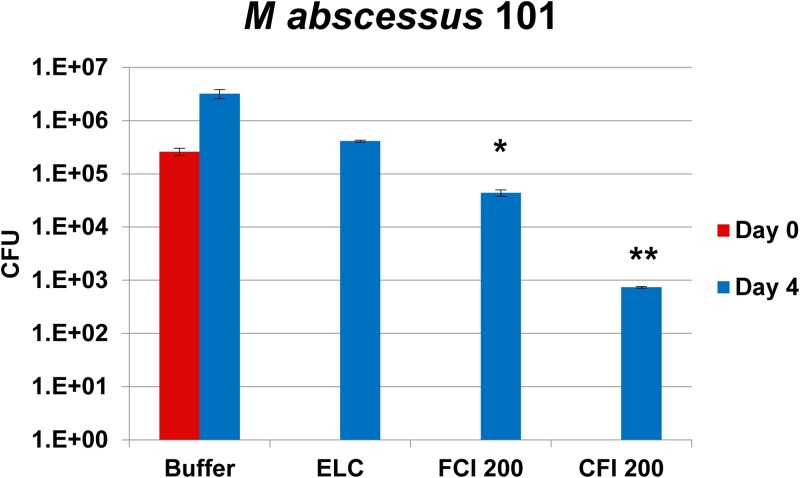

Figure 1 shows the effect of treatment of macrophage monolayers infected with strains MAC101 and MAC109 of M. avium subsp. hominissuis. THP-1 macrophages were exposed to free ciprofloxacin, CFI, or the liposomal formulation containing nanocrystalline ciprofloxacin for 4 days. Exposure to 20 μg/ml of free ciprofloxacin (a concentration approximately 4 times higher than both the serum and tissue level of ciprofloxacin and achievable in the lungs with i.v. or oral ciprofloxacin [15]) had no significant effect on the survival of M. avium subsp. hominissuis 109 and resulted in a 7-fold increase in the intracellular bacterial load (number of CFU) of M. avium subsp. hominissuis MAC101 compared to the initial infecting load. However, treatment with both the CFI and the nanocrystalline liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations at a clinically relevant concentration of 20 μg/ml that is achievable with inhaled CFI (18, 19) was associated with significant reductions of the intracellular bacterial load compared to the initial infecting load in macrophages. For CFI, the decreases were 88% and 72% for M. avium subsp. hominissuis strains MAC101 and MAC109, respectively. Similarly, for the liposomal nanocrystalline formulation, the decreases were 86% and 47% for M. avium subsp. hominissuis strains MAC101 and MAC109, respectively. There were no significant differences in activity between CFI and the liposomal nanocrystalline formulation. Figure 2 and Table 1 show the results of liposomal ciprofloxacin treatment of M. abscessus-infected macrophages. Treatment with high concentrations of free ciprofloxacin (200 μg/ml) resulted in a significant reduction (83%, P < 0.05) of intracellular viable bacteria, which was more pronounced in monolayers treated with CFI (99.7%, ≈3 log, P < 0.02) than in monolayers treated with free ciprofloxacin, compared to the initial infecting load in macrophages on day 0. Ciprofloxacin concentrations of 200 μg/ml are clinically relevant and achievable in the sputum of bronchial airways with inhaled CFI or Linhaliq (18, 19, 28).

FIG 1.

Activity of 20-μg/ml free ciprofloxacin (FCI 20), liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI 20), and liposomal nanocrystalline ciprofloxacin (Nano 20) formulations against M. avium subsp. hominissuis in macrophages. (A) M. avium subsp. hominissuis strain MAC101; (B) M. avium subsp. hominissuis strain MAC109. Values are the mean number of CFU and standard deviations (error bars) on days 0 and 4. *, P < 0.05 compared with the initial infecting load (on day 0) in macrophages.

FIG 2.

Activity of 200 μg/ml of free ciprofloxacin (FCI 200) and liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI 200) against Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus strain MAC101. THP-1 macrophages were infected with M. abscessus (MOI, 2), and after the infection was established (24 h), treatment was started for 4 days. The number of intracellular bacteria (the number of CFU) in the treatment groups after infection (day 4) was compared to the number of intracellular bacteria before treatment (day 0) as well as to the number of bacteria in the untreated buffer control. ELC, empty liposome control with a lipid composition identical to that of CFI at 200 μg/ml. Values are means and standard deviations (error bars). *, P < 0.05 compared to the initial infecting load (on day 0) in macrophages in the untreated buffer control; **, P < 0.02 compared to the initial infecting load (on day 0) in macrophages in the untreated buffer control.

TABLE 1.

Survival of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus strains in macrophages and biofilms exposed to free and liposomal ciprofloxacina

| Strain | Time of bacterial load measurement or treatment | No. of CFU/ml in macrophagesb | Time of bacterial load measurement (day) or treatment | No. of CFU/ml in biofilmsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH1 | 0 | (4.4 ± 0.4) × 105 | 0 | (5.1 ± 0.3) × 105 |

| 3 | (6.1 ± 0.3) × 106 | 7 | (3.8 ± 0.5) × 107 | |

| FCI (20 mg/ml) | (4.8 ± 0.3) × 105* | FCI (100 mg) | (3.0 ± 0.4) × 107 | |

| CFI (20 mg/ml) | (3.6 ± 0.4) × 105* | CFI (100 mg) | (9.2 ± 0.2) × 106 | |

| NIH2 | 0 | (4.0 ± 0.4) × 105 | 0 | (5.6 ± 0.4) × 105 |

| 3 | (6.5 ± 0.5) × 106 | 7 | (3.9 ± 0.4) × 107 | |

| FCI (20 mg/ml) | (5.2 ± 0.4) × 105* | FCI (100 mg) | (2.1 ± 0.6) × 107 | |

| CFI (20 mg/ml) | (3.9 ± 0.4) × 105* | CFI (100 mg) | (8.0 ± 0.4) × 106* | |

| S1 | 0 | (4.5 ± 0.5) × 105 | 0 | (5.4 ± 0.5) × 105 |

| 3 | (6.7 ± 0.5) × 106 | 7 | (4.2 ± 0.3) × 107 | |

| FCI (20 mg/ml) | (5.1 ± 0.3) × 105* | FCI (100 mg) | (2.0 ± 0.4) × 107* | |

| CFI (20 mg/ml) | (2.6 ± 0.4) × 105* | CFI (100 mg) | (9.0 ± 0.4) × 106* |

FCI, free ciprofloxacin; CFI, liposomal ciprofloxacin.

*, P < 0.05.

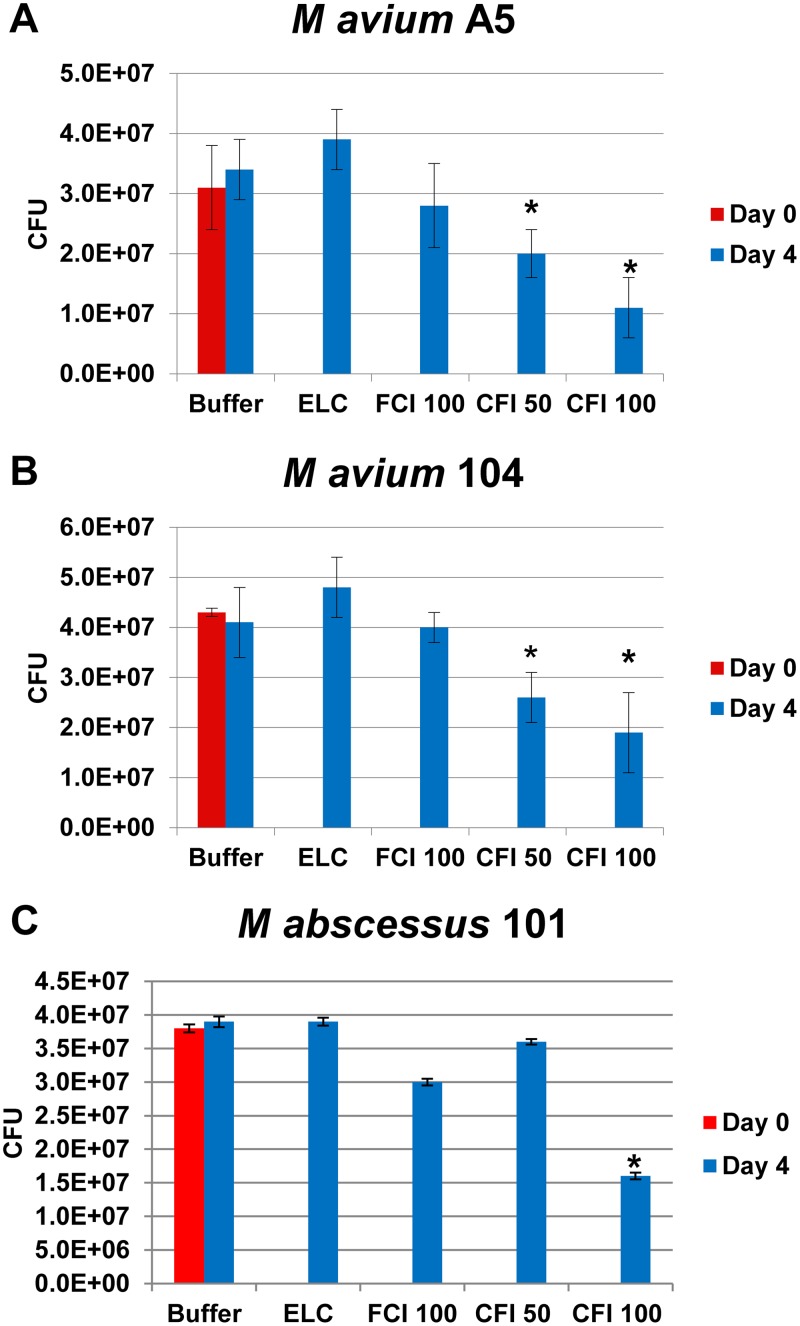

Activity against established biofilms.

Biofilms were established in a 96-well plate for 7 days. The results presented above raised the possibility that macrophages infected with M. avium subsp. hominissuis are less efficient in taking up free ciprofloxacin. Figure 3 and Table 1 show that 50 μg/ml of CFI was associated with significant killing of M. avium subsp. hominissuis, reducing the number of CFU by 35% and 40% for strains A5 and MAC104, respectively, compared to the number of CFU on day 0, while 100 μg/ml of CFI was required to induce a significant killing of M. abscessus in biofilms of 58%. The corresponding reductions for 100 μg/ml CFI were 65% and 56% for M. avium subsp. hominissuis strains A5 and MAC104, respectively.

FIG 3.

Activity of 100 μg/ml of free ciprofloxacin (FCI 100) and 50 and 100 μg/ml of liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI 50 and CFI 100, respectively) against M. avium subsp. hominissuis strain A5 (A) and strain MAC104 (B) and M. abscessus strain 105 (C) biofilms. Mature biofilms were established in 96-well plates as described in Materials and Methods. ELC, empty liposome control with a lipid composition identical to the lipid concentration in CFI at 100 μg/ml. CFU values are means and standard deviations (error bars). *, P < 0.05 for the number of bacteria at day 4 versus day 0 before treatment.

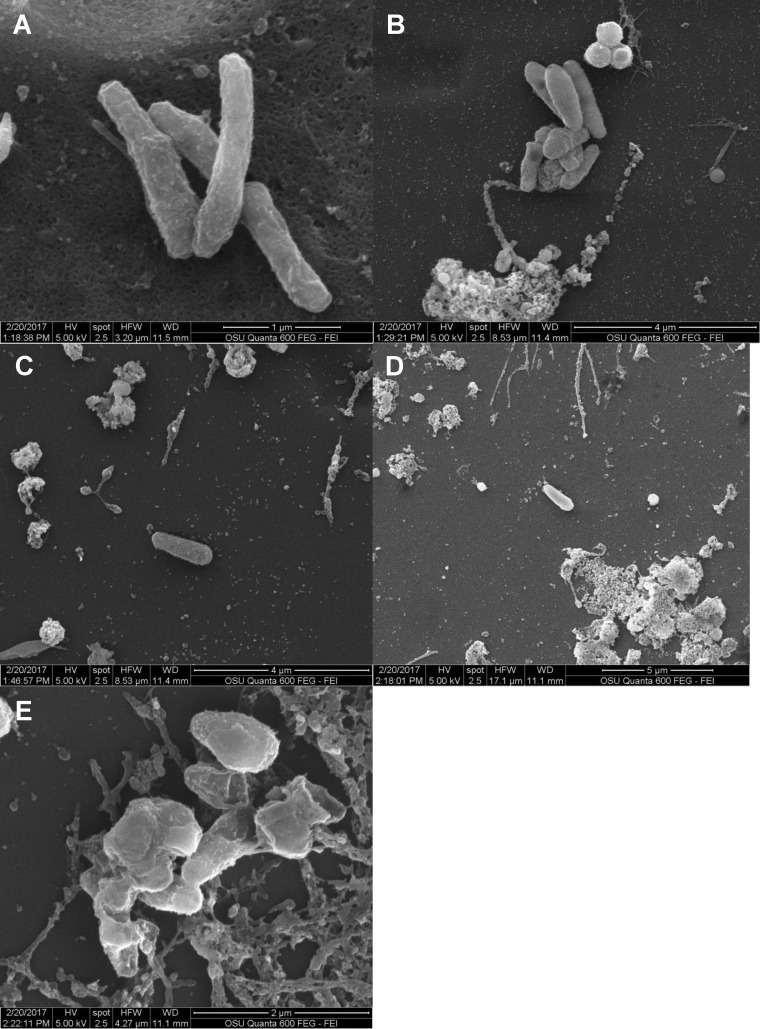

Because the M. avium biofilm is preceded by the formation of microaggregates (23, 27), we then evaluated the role of liposomal ciprofloxacin in interfering with microaggregate formation and subsequent biofilm establishment. Microaggregates were formed by incubating M. avium subsp. hominissuis on the surface of epithelial (HEp-2) cells in the presence of cytochalasin D. Bacteria and treatments (CFI and free ciprofloxacin) were added to the HEp-2 epithelial cell culture at the same time, or the treatments were added to HEp-2 cell-bacteria at different time points after bacterial seeding. As shown in Fig. 4, addition of 200 μg/ml of CFI, a concentration that is achievable in the airways after the inhaled delivery of CFI or Linhaliq (18, 19, 28), to the bacteria forming biofilms in HEp-2 cells significantly inhibited the formation of microaggregates by 43% to 77% compared with that achieved with the untreated buffer control at the same time point when the treatments were added 1 to 4 h after seeding, whereas there were no significant changes with free ciprofloxacin (Fig. 5).

FIG 4.

Effect of 200 μg/ml of free ciprofloxacin (FCI 200) and liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI 200) on the formation of a biofilm on HEp-2 cells. HEp-2 cells were cultured to confluence. An antibiotic formulation was added to the culture once. Bacteria were quantified 24 h after the antibiotic was added. CFU values are means and standard deviations (error bars). *, P < 0.05 compared with untreated buffer control at the same time point.

FIG 5.

Electron micrographs of M. avium subsp. hominissuis microaggregates. (A) Buffer control added at time zero showing the presence of bacterial microaggregates; (B) free ciprofloxacin (200 μg/ml) treatment added at time zero showing less microaggregate formation than that for the control; (C and D) CFI (200 μg/ml) treatment added at time zero before aggregate formation showing the prevention of aggregation; (E) CFI (200 μg/ml) treatment added at 24 h to already present microaggregates showing an unusual bacterial surface.

Treatment of mice infected with MAC strain MAC104.

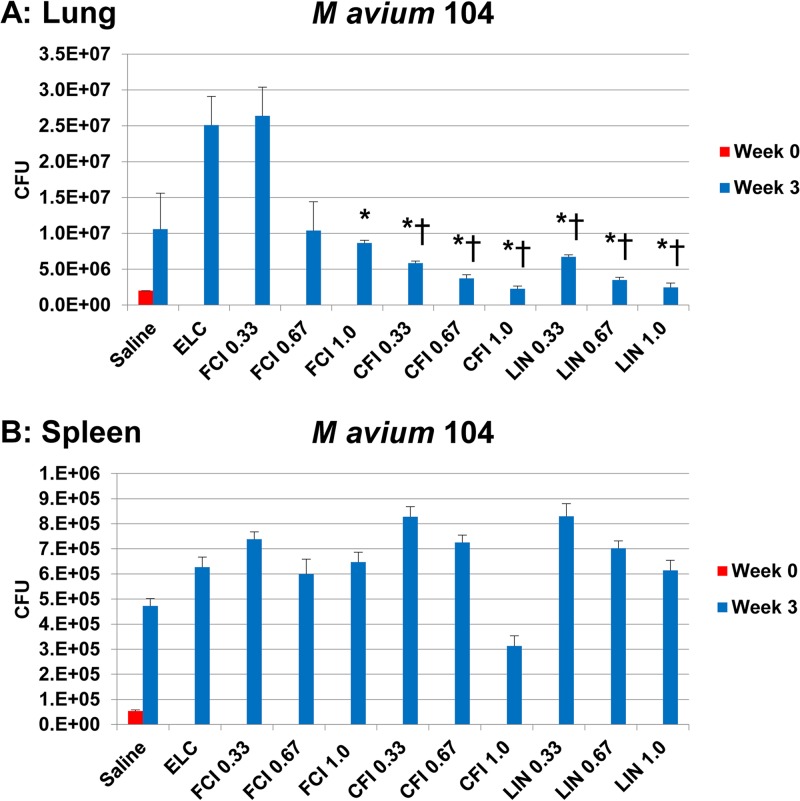

Mice infected by intranasal instillation were treated with intranasally instilled formulations of free ciprofloxacin, liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI), or Linhaliq for 3 weeks; the controls were treated with saline and empty liposomes in which the lipid dose matched the lipid dose in CFI at 1 mg/kg of body weight. Figure 6 shows that both CFI and Linhaliq were effective in significantly reducing the bacterial load in the lung compared with that achieved with the saline control, which is in contrast to the results obtained with empty liposomes or free ciprofloxacin. The effect was found at all three lung doses but was most evident at 1 mg/kg, which produced reductions of 79% and 77% for CFI and Linhaliq, respectively, which were significant compared with the results achieved with saline, the empty liposome control (ELC), and 1 mg/kg free ciprofloxacin, whereas free ciprofloxacin produced a smaller but significant decrease of only 18% compared with the results achieved with saline. The 0.67-mg/kg dose produced significant reductions compared with those achieved with saline of 65% and 67% for CFI and Linhaliq, respectively, which were also significant compared with the results achieved with the empty liposome control and 1-mg/kg free ciprofloxacin; the 0.67-mg/kg free ciprofloxacin dose produced only a small (2%) reduction that was not significant. Lastly, the 0.33-mg/kg dose produced significant reductions compared with those achieved with saline of 45% and 37% for CFI and Linhaliq, respectively, which were also significant compared with the results achieved with the empty liposome control and 1-mg/kg free ciprofloxacin; treatment with the 0.33-mg/kg free ciprofloxacin dose resulted in an increase in the number of CFU.

FIG 6.

Activity of 0.33-, 0.67-, and 1-mg/kg lung doses of free ciprofloxacin (FCI) and liposomal ciprofloxacin (liposomal ciprofloxacin [CFI 0.33, CFI 0.67, and CFI 1.0] and Linhaliq [LIN 0.33, 0.67, and 1.0]) against MAC strain MAC104 in mice over 3 weeks in lung (A) and spleen (B). Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were used. Mice were infected and treated by intranasal instillation. ELC, empty liposome control with a lipid composition identical to that of CFI at 1 mg/kg. CFU values are means and standard deviations (error bars). *, P < 0.05 compared with saline or empty liposome control at week 3; †, P < 0.05 compared with 1-mg/kg free ciprofloxacin at week 3.

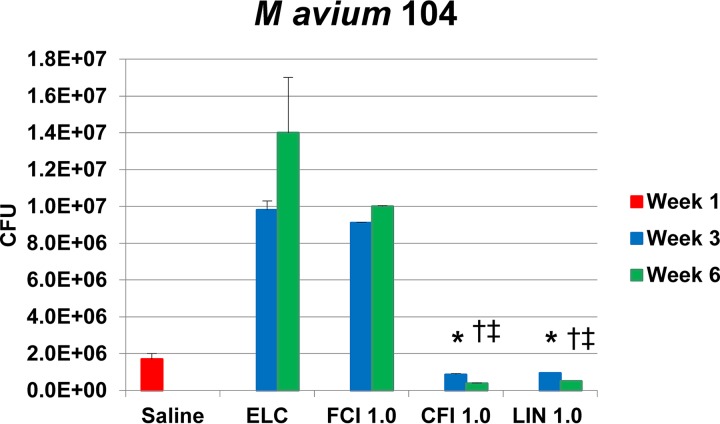

To determine whether treatment for 6 weeks was more effective than treatment for 3 weeks, C57BL/6 mice were infected with MAC104 by an intranasally instilled aerosol and then treated daily for 3 and 6 weeks with 1 mg/kg CFI, Linhaliq, or free ciprofloxacin. As shown in Fig. 6, prolonging treatment for 3 more weeks (6 weeks total) resulted in significantly increased killing of M. avium subsp. hominissuis in the lungs. At 3 weeks, the reductions in the number of CFU compared with those achieved with saline were 49% and 45% for CFI and Linhaliq, respectively, which were significant compared with the results obtained with saline, empty liposomes, and free ciprofloxacin, which produced increases in the number of CFU. There were larger reductions at 6 weeks of 78% and 70% for CFI and Linhaliq, respectively, that were significant compared with the results obtained with saline, empty liposomes, and free ciprofloxacin, as well as the values at 3 weeks (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Efficacy of 1-mg/kg free ciprofloxacin (FCI 1.0) and liposomal ciprofloxacin (liposomal ciprofloxacin [CFI 1.0] and Linhaliq [LIN 1.0]) against MAC strain MAC104 in mice over 3 and 6 weeks. Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were used and were infected and treated by intranasal instillation. ELC, empty liposome control with a lipid concentration identical to that of CFI at 1.0 mg/kg. CFU values are means and standard deviations (error bars). *, P < 0.05 compared with saline at week 1; †, P < 0.05 compared with the empty liposome control after infection (day 4) in the same week 1; ‡, P < 0.05 for the parameter at week 6 compared to week 3.

Establishment of a mouse model of M. abscessus lung infection.

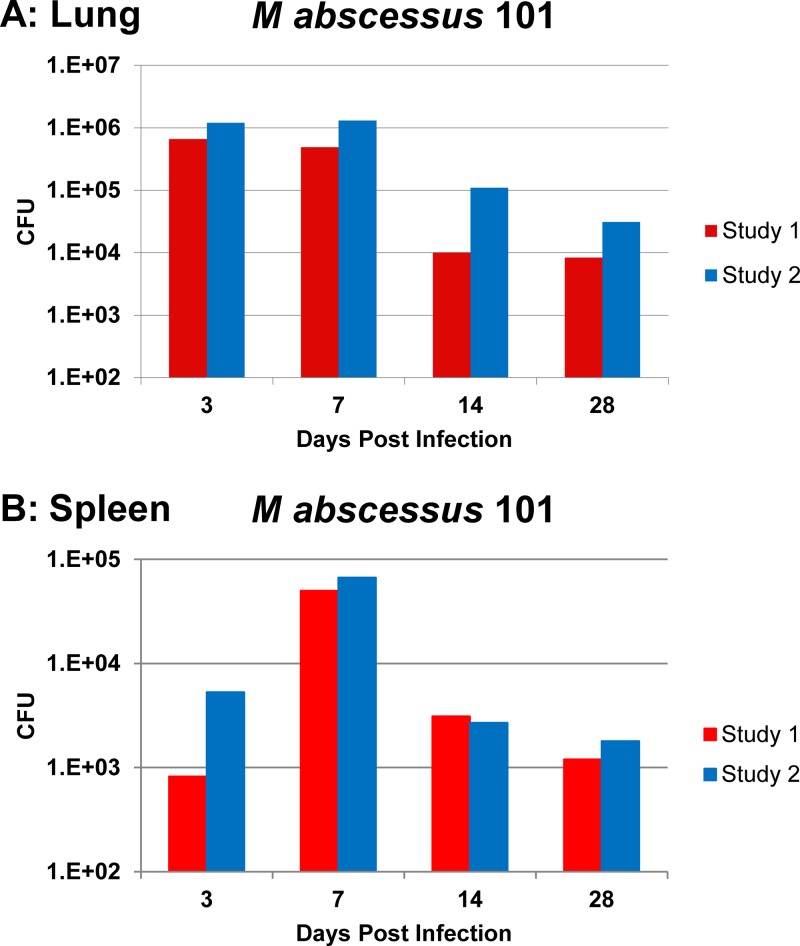

Because of the lack of virulence of M. abscessus in mice, it has been difficult to establish a reproducible and relevant test system in which experimental therapies for M. abscessus can be evaluated. We investigated a few mouse strains (data not shown) and found that the model comprising C57BL/6 beige bj/bj mice infected by intranasal inoculation consistently produces infection with M. abscessus. Mice (12 mice per time point) were infected intranasally with 5 × 107 M. abscessus strain 101, and the number of bacteria in the lung and spleen was quantified at days 3, 7, 14, and 28. The results are shown in Fig. 8. In the two studies, there was approximately 6 × 105 to 1.3 × 106 CFU in the lung from day 3 to day 7, approximately 104 to 105 CFU at day 14, and about 8 × 103 to 3 × 104 CFU at day 28. The spleen had approximately 1.2 × 103 to 6.7 × 104 CFU from days 7 to 28. Thus, by using the beige mouse and the respiratory tract as the route of infection, we established a sustained infection by M. abscessus. It is important to notice that the inoculum used was small compared with that used in other mouse models.

FIG 8.

Mean number of CFU of M. abscessus strain 101 in lung (A) and spleen (B) in two studies in C57BL/6 beige bj/bj mice. Mice were infected with 1 × 107 CFU by intranasal instillation, observed for the stated number of days, and then harvested, and the lungs and spleen were plated onto Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates.

Treatment of mice infected with M. abscessus.

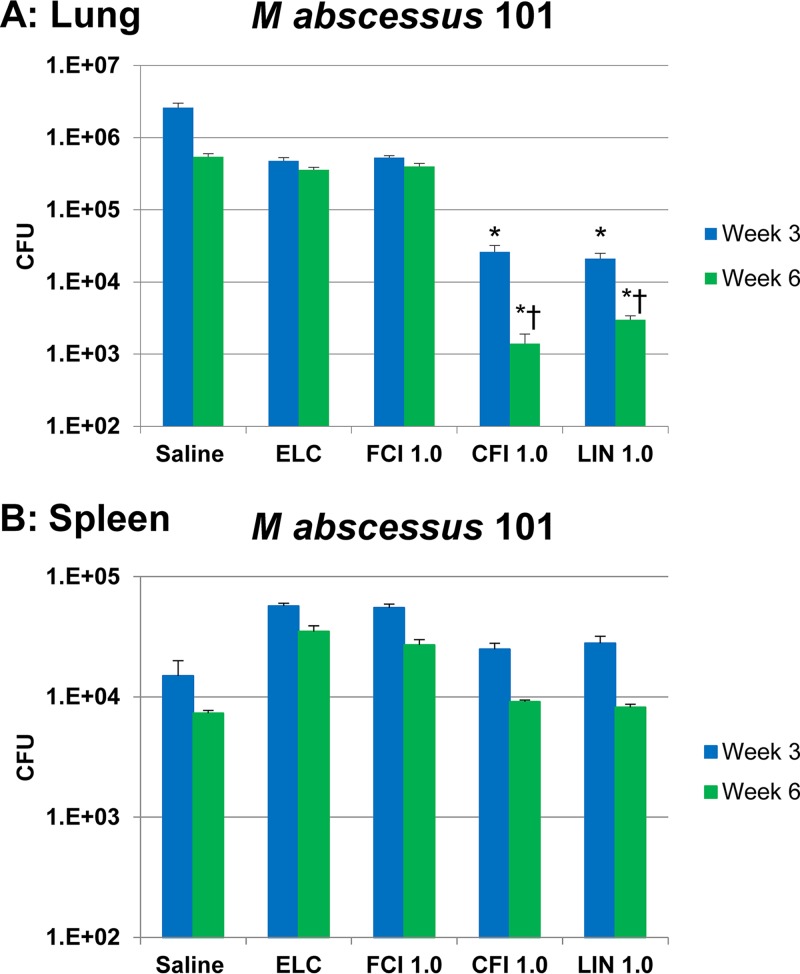

We employed the above-described C57BL/6 beige bj/bj mouse model to examine the activity of liposomal ciprofloxacin and free ciprofloxacin against M. abscessus. Because the data for M. avium subsp. hominissuis in the mouse (see above) demonstrated that 6 weeks of treatment had increased activity, we decided to study the effect of therapy for both 3 and 6 weeks. C57BL/6 beige bj/bj mice (n = 12 mice per group per time point) were infected by intranasal inoculation with (5.4 ± 0.3) × 107 CFU of M. abscessus 101. Three weeks later (week 0), therapy was initiated with CFI, Linhaliq, or free ciprofloxacin at a lung dose of 1 mg/kg delivered daily by intranasal instillation for 3 and 6 weeks; the controls were treatment with saline and empty liposomes in which the lipid dose matched the lipid content of the 1-mg/kg CFI dose. At the end, mice were harvested and the lungs and spleens were plated for determination of bacterial counts. The results are shown in Fig. 9. Compared to the number of CFU for the untreated saline control-treated mice at week 3, treatment with CFI and Linhaliq reduced the number of CFU in the lung at 3 weeks by 95.2% and 96.1%, respectively, which was significant compared with the results obtained with saline, empty liposomes, and free ciprofloxacin. There were further reductions at week 6 by 99.7% (≈3 logs) and 99.4% (>2 logs), respectively, which were significant compared with the results obtained with saline, empty liposomes, and free ciprofloxacin and the number of CFU at 3 weeks. Free ciprofloxacin or empty liposome treatment did not result in significant reductions in bacterial counts in either the lungs or spleen compared with those in untreated mice at either 3 or 6 weeks.

FIG 9.

Efficacy of 1 mg/kg of free ciprofloxacin (FCI 1.0) and liposomal ciprofloxacin (liposomal ciprofloxacin [CFI 1.0] and Linhaliq [LIN 1.0]) in the treatment of M. abscessus strain 101 infection in the lung (A) and spleen (B). C57BL/6 beige bj/bj mice were infected with (5.4 ± 0.3) × 107 CFU in 0.5 ml of HBSS by intranasal instillation; treatment was also by intranasal instillation. ELC, empty liposome control with a lipid composition identical to that in CFI at 1 mg/kg. Values are means and standard deviations (error bars). *, P < 0.05 compared with saline, the empty liposome control, and free ciprofloxacin in the same week; †, P < 0.05 for the parameter at week 6 compared to week 3.

DISCUSSION

Current treatments of NTM lung infections are a clinical challenge because of both the frequent adverse effects and efficacy issues. The ability to resist intracellular killing and to form robust biofilms can impart extreme resistance of the NTM in the lung to the action of antibiotics (9, 10). The routine treatment of NTM is via oral administration and intravenous administration in the case of more severe disease. As a common aspect, NTM infection results in a progressive decrease in lung function. The systemically administered antibiotics reach the lung by the systemic circulation, and the ability to achieve desirable antibacterial concentrations at the site of the infection is difficult and needs to be balanced vis-à-vis the risk of systemic toxicity. For example, ciprofloxacin, when administered orally or intravenously at safe approved doses, achieves a concentration in lung tissue of approximately 3 to 4 μg/ml, which is insufficient to kill or even inhibit either M. avium subsp. hominissuis or M. abscessus (15, 29). Although antibiotics in the class of quinolones kill many strains of NTM in vitro, due to the clear limitations of antibiotics for the treatment of NTM lung infections when delivered orally or intravenously, an alternative form of therapy is needed.

In this report, we describe the evaluation of liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations delivered directly to the airways for the therapy of infections cause by M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. abscessus (Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii and M. abscessus subsp. abscessus) in macrophages, biofilms, and mice. The results suggest that this topical liposomal ciprofloxacin is associated with significant killing of NTM. NTM in vivo have several different phenotypes: two of them are intracellular in macrophages and mucosal epithelial cells; there is an extracellular form in cavities or nodes as well as in biofilms that almost certainly contributes to the frequently disappointing results achieved with systemic therapy. In addition, recent information has shown that both M. avium complex and M. abscessus have the ability to export DNA when expressing the biofilm phenotype (8), resulting in the establishment of a very robust biofilm (8). The biofilm is resistant to antibiotic penetration and may harbor nonreplicating bacteria, creating one more obstacle to the ultimate efficacy of therapy (16).

The combination of the encapsulation of ciprofloxacin in liposomes with the direct delivery of the formulation to the lungs makes therapy with inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin fundamentally different and has several advantages compared to oral and parenteral products of ciprofloxacin and other antibiotics in terms of biodistribution and pharmacokinetics, improving the potential for better safety and efficacy. The liposome-encapsulated ciprofloxacin is delivered at very high concentrations directly to the respiratory tract, where it resides over a prolonged period of time, during which ciprofloxacin is slowly released from the liposomes to the site of infection in the lungs and produces a systemic exposure lower than that achieved with oral or intravenous ciprofloxacin (17–19, 21, 28).

Another advantage of liposomes is that they are also phagocytized by macrophages, bringing both the bacteria and the ciprofloxacin-laden liposomes into close proximity within the phagosomes, which amplifies the bioavailability of ciprofloxacin at the infected target. This effect should lead to improved efficacy compared with that of systemically delivered ciprofloxacin or other antimycobacterial agents. NTM are also able to form biofilms; another advantage of liposomal formulations is their ability to penetrate biofilms (24), which improves efficacy compared with that of nonliposomal antibiotics.

These properties of the various liposomal formulations of ciprofloxacin are confirmed by the results of experiments with the biofilm, macrophage, and mouse models reported here.

In contrast, free ciprofloxacin had efficacy inferior to that of liposomal ciprofloxacin in all the studies conducted and described in this paper.

In patients at risk of the establishment of chronic infection with NTM, the administration of inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin at early times postinfection may provide protection from chronic NTM disease. At a clinically relevant concentration of 200 μg/ml, CFI suppressed the formation of microaggregates by M. avium subsp. hominissuis, shown to be a crucial step in the formation of biofilms.

In summary, the studies reported here showed that the liposomal formulations of ciprofloxacin delivered into the airways may offer significant advantages over the standard oral or intravenous formulations of ciprofloxacin for the treatment of both M. avium subsp. hominissuis and M. abscessus lung infections. However, these topically instilled formulations did not show a significant effect on NTM infections that spread from the respiratory tract to the spleen.

For these reasons and also because NTM therapy routinely combines several drugs, evaluation of inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin in combination with oral drugs could be an interesting extension of the research reported here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Three liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations were tested: CFI (also known as ciprofloxacin for inhalation); Linhaliq (a mixture of CFI and free ciprofloxacin), a nanocrystalline formulation of ciprofloxacin encapsulated within liposomes; and an empty liposome formulation with no drug, which was also used as a control (empty liposome control [ELC]). All formulations were provided by Aradigm Corp. (Hayward, CA). The CFI formulation contains 50 mg/ml ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (HCl) in 25 mM histidine, 145 mM NaCl, pH 6.0, buffer encapsulated in liposomes composed of hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol, which provide the sustained slow release of the drug (16, 17, 21). The Linhaliq formulation is a 1:1 volume-to-volume mixture of CFI (50 mg/ml) and free ciprofloxacin (20 mg/ml ciprofloxacin HCl) in an acetate-buffered aqueous formulation at pH 3.3, resulting in a final concentration of 35 mg/ml ciprofloxacin HCl (16, 17, 21). The rationale for Linhaliq is to combine the advantages of an initial transient high concentration of free ciprofloxacin to increase the maximum concentration in the lungs from the free ciprofloxacin component of Linhaliq with the slow release of ciprofloxacin from the CFI (liposomal component) (17, 21). Free ciprofloxacin (20 mg/ml ciprofloxacin HCl) was used both to formulate Linhaliq and as a comparator. The recently discovered nanocrystalline formulation modulates the rate of drug release through the formation of ciprofloxacin nanocrystals within the liposomes. These liposomes have a lower rate of release of ciprofloxacin in an in vitro assay than traditional liposomes (21). Thus, the nanocrystals may be more effective at killing the NTM within the macrophages or biofilms than other formulations because of the higher drug concentrations persisting in the proximity of the mycobacteria over a longer period of time. The nanocrystalline formulation was made by diluting CFI 4-fold to 12.5 mg/ml in 90 mg/ml sucrose, pH 6.0, followed by freeze-thaw in liquid nitrogen.

Empty liposomes with a size and composition comparable to those of CFI (formulated in isotonic 25 mM histidine buffer at pH 6.0) but without drug were manufactured. Dilutions to the desired concentrations were made for CFI, the nanocrystals, and empty liposomes using 25 mM histidine, 145 mM NaCl, pH 6.0, buffer; for Linhaliq, a 1:1 mixture of the two buffers (i.e., the 12.5 mM histidine buffer and the 5 mM acetate buffer) was used; and for free ciprofloxacin, 10 mM acetate buffer was used to maintain the pH at 3.3.

Mycobacteria.

Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis strains A5, MAC104, MAC109, and MAC101 were isolated from patients as previously described (15). Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus strains NIH1, NIH2, and S1 were isolated from patients with either a bacterial infection or a lung infection. Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii strain 101 was isolated from the lung of a patient. Bacteria were confirmed to belong to the indicated species by use of a commercially available DNA probe (GenProbe Inc.) and the 16S rRNA gene sequence. Before macrophage and mouse infections, organisms were suspended in Hanks' balanced salt solutions (HBSS), and the concentration of the bacterium per milliliter was adjusted according to a previously published protocol (15). The suspension was then plated onto Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates containing oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase (OADC) to determine the number of bacteria in the inoculum.

Macrophages and macrophage killing assay.

Human macrophage cell line THP-1, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Chicago, IL) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma Chemicals Co) and 2 ml of l-glutamine. The assays were performed as previously described (22). Briefly, THP-1 cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells, and maturation was induced by incubation with 5 μg/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) overnight. Then, the monolayers were washed to remove the PMA, and the RPMI 1640 medium was replenished. Mononuclear phagocytes were then infected with a dispersed suspension of mycobacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for M. avium subsp. hominissuis and an MOI of 1 to 2 for M. abscessus. The actual number of bacteria in the final suspension was determined by plating the inoculum onto 7H10 agar plates (22). Infection of phagocyte monolayers was allowed to take place for 1 h, and then the monolayers were washed three times with HBSS to remove the extracellular bacteria. Control infected monolayers were lysed with sterile water containing 0.05% SDS and plated onto 7H10 agar plates to quantify the number of bacteria taken up by macrophages, as previously reported (22). Macrophage monolayers were treated with the liposomal ciprofloxacin formulation (CFI; 20 or 200 μg/ml), the liposomal nanocrystalline ciprofloxacin (20 μg/ml) (for M. avium subsp. hominissuis only), free ciprofloxacin (20 or 200 μg/ml), empty liposomes (with the lipid concentration matching the lipid concentration in the CFI formulation with a 200-μg/ml concentration), or a buffer control (no antibiotic) for 4 days (the medium was changed daily) and then lysed to quantify the number of viable intracellular bacteria according to the published method (22). The number of THP-1 macrophages in the monolayers was monitored as described previously (22). The final macrophage lysate suspension was serially diluted, and 0.1 ml of the bacterial suspension was plated onto 7H10 agar. The plates were allowed to dry at room temperature for 15 min and then incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 3 weeks or 4 to 5 days, depending on the mycobacterial species. Each assay was performed in triplicate, and each experiment was performed 4 independent times.

Biofilm.

Biofilm has been suggested to be an important aspect of the pathogenesis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection of the lung (6–8). To determine whether the liposomal ciprofloxacin was able to decrease the bacterial load in the biofilm, M. avium subsp. hominissuis strain MAC104 and M. abscessus strain 101 were seeded onto polyvinylchloride plates as previously described (8). The biofilm was treated daily with the liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI) only (50 and 100 μg/ml), free ciprofloxacin (100 μg/ml), empty liposomes with the lipid concentration matching the lipid concentration of the high CFI (100 μg/ml) concentration, or the buffer control (no antibiotic). The supernatant of the biofilm was removed daily before treatment without disturbing the biofilm. After the treatment period, the biofilm was homogenized and the suspension was plated onto 7H10 agar for quantification of the number of viable bacteria.

For the formation of microaggregates, HEp-2 epithelial cells (ATCC) in culture (100% confluence) in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS were incubated with M. avium subsp. hominissuis (105 bacteria) for 24 h in the presence of cytochalasin D to inhibit bacterial uptake, and then M. avium subsp. hominissuis was harvested as previously described (23). Liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI, 200 μg/ml) and free ciprofloxacin (200 μg/ml) were added to the culture once at 0 to 24 h after seeding.

Mouse models.

The studies were approved by the IACUC from Oregon State University, with the number 4939. To determine whether the liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations were effective in vivo for the treatment of M. avium subsp. hominissuis infection, female C57BL/6 mice weighing approximately 20 g (The Jackson Laboratory, ME) were used after a 1-week quarantine period. For the infection, the mice were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane and a micropipette was used to introduce the bacterial inoculum into the airways. Mice were infected with 1 × 108 CFU in a suspension of Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) strain MAC104, delivered to the airways via the animals' nostrils. The mice were then observed for 3 weeks, and after that period, 6 mice were harvested to establish the infection baseline prior to treatment. Lung and spleens were collected, aseptically dissected, weighed, and then homogenized in 3 ml of Middlebrook 7H9 broth containing 20% glycerol. The homogenate was serially diluted in HBSS and then plated onto 7H10 plates containing 1% OADC. The mice were then treated daily for 3 or 6 weeks with liposomal ciprofloxacin (CFI) or Linhaliq with lung doses of 0.33, 0.67, or 1 mg/kg; free ciprofloxacin with the same lung doses; empty liposomes with the lipid dose matching the lipid dose of the high CFI (1 mg/kg) dose; or saline (no antibiotic) as a control by intranasal instillation at the dose desired.

Because there is a general lack of a reliable mouse model for M. abscessus infection, a model system was established using C57BL/6 bj/bj mice. Mice were infected with 1 × 107 bacteria intranasally, and the infection was allowed to become established for 3 weeks. Afterwards, mice were harvested at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days, and the bacterial loads in the lung and spleen were determined as reported previously (24). For the M. abscessus infection, we used C57BL/6 bj/bj mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Mice were infected with 5.4 × 107 bacteria by the intranasal instillation of formulations delivered into the airways and were observed for 3 weeks before the beginning of treatment. At the end of the 3-week infection period, 6 mice were harvested and the bacterial load in the lung and spleen was determined after plating of lung and spleen tissue homogenates onto 7H10 agar plates. Treatment was then initiated with antibiotic formulations as described above.

Following daily treatment for 3 weeks and 6 weeks, the mice were allowed 24 h without administration of therapy for clearance of the treatment substances and then harvested. After harvesting, the lung and spleen were homogenized and plated onto 7H10 with OADC and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 days.

Lungs from uninfected as well as infected and treated mice were harvested, fixed with 2% formaldehyde, and prepared for histopathology as previously described (24).

Statistical analysis.

In vitro experiments were repeated at least 4 times, and the in vivo studies in mice were repeated twice. The results were analyzed by comparing the results for the experimental groups with those for the control groups. Student's t test was used to verify the significance of the results. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1RA43AI106188).

We thank Janice Blouse and Carolyn Cowan for preparing the manuscript.

J.D.B. designed the experiments, provided the compounds, and wrote the paper. V.E. performed the in vivo studies. D.C. designed the experiments, provided the compounds, and wrote the paper. I.G. designed the experiments, provided the compounds, and wrote the paper. L.E.B. designed the experiments, performed assays, and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prevots DR, Marras TK. 2015. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clin Chest Med 36:13–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassidy PM, Hedberg K, Saulson A, McNelly E, Winthrop KL. 2009. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and risk factors: a changing epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis 49:e124–e129. doi: 10.1086/648443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodle EE, Cunningham JA, Della-Latta P, Schluger NW, Saiman L. 2008. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients without HIV infection, New York City. Emerg Infect Dis 14:390–396. doi: 10.3201/eid1403.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, Jackson LA, Raebel MA, Blosky MA, Montes de Oca R, Shea YR, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Olivier KN. 2010. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182:970–976. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falkinham JO., III 2011. Nontuberculous mycobacteria from household plumbing of patients with nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Emerg Infect Dis 17:419–424. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.101510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qvist T, Eickhardt S, Kragh KN, Andersen CB, Iversen M, Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T. 2015. Chronic pulmonary disease with Mycobacterium abscessus complex is a biofilm infection. Eur Respir J 46:1823–1826. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01102-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose SJ, Bermudez LE. 2016. Identification of bicarbonate as a trigger and genes involved with extracellular DNA export in mycobacterial biofilms. mBio 7:e01597-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01597-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose SJ, Bermudez LE. 2014. Mycobacterium avium biofilm attenuates mononuclear phagocyte function by triggering hyperstimulation and apoptosis during early infection. Infect Immun 82:405–412. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00820-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang JH, Kao PN, Adi V, Ruoss SJ. 1999. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare pulmonary infection in HIV-negative patients without preexisting lung disease: diagnostic and management limitations. Chest 115:1033–1040. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daley CL, Griffith DE. 2010. Pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 14:665–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K, ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee, American Thoracic Society, Infectious Disease Society of America. 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.175.7.744 (Erratum, 175:744-745.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace RJ Jr, O'Brien R, Glassroth J, Raleigh J, Asim Dutt A. 1990. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am Rev Respir Dis 142:940–953. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yajko DM, Nassos PS, Hadley WK. 1987. Therapeutic implications of inhibition versus killing of Mycobacterium avium complex by antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 31:117–120. doi: 10.1128/AAC.31.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu J, Nussbaum J, Bozzette S, Tilles JG, Young LS, Leedom J, Heseltine PN, McCutchan JA. 1990. Treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in AIDS with amikacin, ethambutol, rifampin, and ciprofloxacin. California Collaborative Treatment Group. Ann Intern Med 113:358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergogne-Bérézin E. 1993. Pharmacokinetics of fluoroquinolones in respiratory tissues and fluids. Quinolones Bull 10:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cipolla D, Wu H, Eastman S, Redelmeier T, Gonda I, Chan HK. 2014. Development and characterization of an in vitro release assay for liposomal ciprofloxacin for inhalation. J Pharm Sci 103:314–327. doi: 10.1002/jps.23795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cipolla D, Blanchard J, Gonda I. 2016. Development of liposomal ciprofloxacin to treat lung infections. Pharmaceutics 8:E6. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics8010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruinenberg P, Serisier D, Cipolla D, Blanchard J. 2010. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and antimicrobial activity of inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin formulations in humans. Pediatr Pulmonol 45(S33):354. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruinenberg P, Blanchard JD, Cipolla DC, Dayton F, Mudumba S, Gonda I. 2010. Inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin: once a day management of respiratory infections, p 73–81. In Dalby RN, Byron PR, Peart J, Suman JD, Farr SJ, Young PM (ed), Proceedings of respiratory drug delivery. Davis Healthcare International Publishing, River Grove, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haworth CS, Wanner A, Froehlich J, O'Neal T, Davis A, Gonda I, O'Donnell A. 2017. Inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin in patients with bronchiectasis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: results from two parallel phase III trials (Orbit-3 and -4), abstr B14. Abstr 2nd World Bronchiectasis Conf, Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipolla D, Wu H, Salentenig S, Boyd B, Rades T, Vanhecke D, Petri-Fink A, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Eastman S, Redelmeier T, Gonda I, Chan H-K. 2016. Formation of drug nanocrystals under nanoconfinement afforded by liposomes. RSC Adv 6:6223–6233. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordao L, Bleck CK, Mayorga L, Griffths G, Anes E. 2008. On the killing of mycobacteria by macrophages. Cell Microbiol 10:529–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mugabe C, Halwani M, Azghani AO, Lafrenie RM, Omri A. 2006. Mechanism of enhanced activity of liposome-entrapped aminoglycosides against resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2016–2022. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01547-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meers P, Neville M, Malinin V, Scotto AW, Sardaryan G, Kurumunda RMackinson C, James G, Fisher S, Perkins WR. 2008. Biofilm penetration, triggered release and in vivo activity of inhaled liposomal amikacin in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. J Antimicrob Chemother, 61:859–868. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia Y, Joly H, Omri A. 2010. Characterization of the interaction between liposomal formulations and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Liposome Res 20:134–146. doi: 10.3109/08982100903218892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serisier DJ, Bilton D, De Soyza A, Thompson PJ, Kolbe J, Greville HW, Cipolla D, Bruinenberg P, Gonda I, ORBIT-2 Investigators. 2013. Inhaled, dual release liposomal ciprofloxacin in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (ORBIT-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Thorax 68:812–817. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babrak L, Danelishvili L, Rose SJ, Kornberg T, Bermudez LE. 2015. The environment of “Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis” microaggregates induces synthesis of small proteins associated with efficient infection of respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun 83:625–636. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02699-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Froehlich J, Cipolla D, DeSoyza A, Morrish G, Gonda I. 2017. Inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: pharmacokinetics of once-daily inhaled ARD-3150, abstr B33. Abstr 2nd World Bronchiectasis Conf, Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritrovato CA, Deeter RG. 1991. Respiratory tract penetration of quinolone antimicrobials: a case in study. Pharmacotherapy 11:38–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]