The emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in foodborne bacteria is a growing concern worldwide. AMR surveillance is a key element in understanding the implications resulting from the use of antibiotics for therapeutic as well as prophylactic needs.

KEYWORDS: Vibrio spp., antimicrobial resistance, surveillance, molluscan shellfish

ABSTRACT

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in foodborne bacteria is a growing concern worldwide. AMR surveillance is a key element in understanding the implications resulting from the use of antibiotics for therapeutic as well as prophylactic needs. The emergence and spread of AMR in foodborne human pathogens are indirect health hazards. This surveillance study reports the trend and pattern of AMR detected in Vibrio species isolated from molluscs harvested in Canada between 2006 and 2012 against 19 commonly used antibiotics. Five common antibiotics, ampicillin, cephalothin, erythromycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin, predominantly contributed to AMR, including multidrug resistance (MDR) in the molluscan Vibrio spp. isolated in 2006. A prospective follow-up analysis of these drugs showed a declining trend in the frequency of MDR/AMR Vibrio spp. in subsequent years until 2012. The observed decline appears to have been influenced by the specific downturn in resistance to the aminoglycosides, kanamycin, and streptomycin. Frequently observed MDR/AMR Vibrio spp. in seafood is a potential health concern associated with seafood consumption. Our surveillance study provides an indication of the antibiotics that challenged the marine bacteria, sourced to Canadian estuaries, during and/or prior to the study period.

INTRODUCTION

Halophilic “non-cholera” Vibrio species, particularly V. parahaemolyticus and V. alginolyticus, are natural inhabitants of estuarine waters around the world, making them suitable for monitoring ecosystem challenges, such as the impact of using antibiotics and chemicals in aquaculture, farms, and clinical facilities. The use of antibiotics in aquaculture and animal husbandry for prophylaxis and growth promotion has the potential to affect human and animal health. Of various ecological environments, the estuarine ecosystem provides an interactive opportunity for the marine bacteria to encounter washouts containing residues of antibiotics from farmlands and hospitals, making estuaries the most dynamic natural habitat to complement or confirm events from the nearby lands (1). Antibiotic resistance genes predate our use of antibiotics, and the first direct evidence was reported after an analysis of DNA sequences recovered from Late Pleistocene permafrost sediments indicating that antibiotic resistance is an ancient, naturally occurring phenomenon detectable in the environment (2). Antimicrobial selective pressure is particularly high in hospitals where inpatients, for example, in 20% to 30% of cases in Europe, receive a dose of antibiotics during hospitalization and treatment (3). In Canada, over 150 billion liters of untreated or undertreated sewage are dumped into the waterways every year (4), and the amount of polluting materials, including antibiotics, is not always controlled. Some of the marine bacteria, including halophilic Vibrio spp., survive antibiotic exposure by acquiring antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mechanisms. The exchange of resistance determinants between the aquatic and the terrestrial environments can result from the transfer and interaction of AMR bacteria between the two environments. The consumption of fishery products is on the rise among health conscious consumers and seafood lovers, which may partly be the reason for the increase in seafood-borne illnesses.

Antibiotics have been a critical public health tool since the discovery of penicillin in 1928 by Alexander Fleming. The introduction of the drug as a therapeutic agent in the 1940s saved the lives of millions of people around the world (5). Thereafter, antimicrobial drugs of various other classes, subclasses, and their subsequent generations were introduced to the therapeutic regimen to fight bacterial infections. However, within a few years of introducing the antibiotics, the emergence of drug resistance in bacteria capable of inactivating drugs, or blocking their action or entry into the cell, reversed the gains of the beneficial discoveries. Hence, many important drug choices for the treatment of bacterial infections have become limited and can yield unpredictable results. At the same time, not much progress has been made in the discovery of new antibiotics, and challenges remain for the future (6). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that an estimated 2 million illnesses and 23,000 deaths are caused by drug-resistant bacteria in the United States alone (7). The European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC) reported that macrolide use was the main driver behind the emergence of macrolide resistance in streptococci and documented a positive correlation between the level of antibiotic resistance and the level of antibiotic consumption (8).

Effective intervention with antibiotics and the proper stewardship of antibiotic use will require evidence-based knowledge regarding the status of AMR at regional and national levels. The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed and initiated a Global Action Plan on AMR in 2015 (9); one of the strategic objectives of the plan was to strengthen the evidence base through enhanced surveillance and analyses. Thereafter, the Global AMR Surveillance System (GLASS) was adopted to enable standardized and comparable data to be collected, analyzed, and shared between countries for advocacy and preventative action. Of the many gaps identified by the WHO reports (9, 10), information on Vibrio spp. of marine origin with AMR profiles and their impact on public health is lacking. A prospective follow-up of bacterial AMR patterns, as observed in the molluscan Vibrio spp., studied over a long period of time can provide information on potential trends occurring from the widespread use of antibiotics and its direct or indirect impacts on human health. Similar AMR data on selected bacteria from terrestrial animals are reported by the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) to understand trends in antimicrobial use and resistance for the benefit of intervention and therapeutic strategies (11, 12). The evidence of resistance to clinically important antimicrobials among selected bacteria isolated from retail meats in Canada has shown a wide variation over time and across regions covering farmlands and poultry (13). Clinically significant AMR Vibrio spp. can be ingested by humans through seafood and can potentially lead to serious consequences. This study reports our findings on the extent and dynamics of AMR detected predominantly among halophilic Vibrio species (V. alginolyticus, V. parahaemolyticus, V. cholerae, V. vulnificus, V. fluvialis, and other unidentified Vibrio spp.) used as indicator bacteria isolated from molluscs, such as oysters, mussels, or clams, harvested in Canadian estuaries from 2006 to 2012.

RESULTS

Resistance and virulence profiles detected by surveillance.

Halophilic Vibrio species, which accumulated in filter-feeding molluscs asymptomatically in the estuarine habitat, displayed resistance, including multidrug resistance ([MDR], resistance to three or more antibiotics), to some of the 19 antibiotics used in this study. In addition, potential virulence factor genes (tdh and/or trh) were detected by PCR in some of the (AMR) isolates. Overall, 343 mollusc samples were tested during the summer months of each year from 2006 to 2012, yielding six different Vibrio species with various frequencies of detection (Table 1). Multiple isolates and/or species belonging to the genus Vibrio were captured from most of the samples. In total, 1,021 strains of Vibrio species (Table 2) were isolated during the study period, yielding an average of three isolates per sample. Only 4.9% of the isolates tested sensitive to all 19 drugs. A total of 319 (31.2%) and 588 (57.6%) of the isolates were identified as V. parahaemolyticus and V. alginolyticus, respectively, of which 47 V. parahaemolyticus isolates (14.7%) tested positive for either of the virulence markers (tdh and trh) (rarely for both) by PCR, and 3 V. alginolyticus isolates (0.5%) tested positive for the trh marker by PCR. These potential pathogens harbored variable AMR profiles, including some (n = 17) V. parahaemolyticus isolates showing MDR. Of the 17 MDR isolates, four were tdh and trh positive and the remainder were tdh negative trh positive by PCR.

TABLE 1.

Total numbers of molluscan samples tested during May to October of each year from Canadian harvest sites on both coasts

| Yr | Total no. of samples tested | East (Atlantic) coast |

West (Pacific) coast |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of samples | No. of samples (%) positive for: |

No. of samples | No. of samples (%) positive for: |

||||||||||||

| V. parahaemolyticus | V. alginolyticus | V. vulnificus | V. cholerae | V. fluvialis | Unidentified Vibrio spp. | V. parahaemolyticus | V. alginolyticus | V. vulnificus | V. cholerae | V. fluvialis | Unidentified Vibrio spp. | ||||

| 2006 | 31 | 15 | 8 | NIa | 0 | 0 | NI | NI | 16 | 10 | NI | 0 | 0 | NI | NI |

| 2007 | 37 | 18 | 8 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 12 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2008 | 46 | 22 | 8 | 19 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 24 | 15 | 22 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| 2009 | 59 | 27 | 10 | 26 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 32 | 15 | 32 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| 2010 | 62 | 29 | 16 | 29 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 33 | 18 | 32 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| 2011 | 54 | 23 | 12 | 22 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 31 | 12 | 27 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| 2012 | 54 | 23 | 21 | 23 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 31 | 23 | 31 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Sum | 343 | 157 | 83 (53) | 132 (93)b | 33 (21) | 2 (1) | 12 (8)b | 24 (17)b | 186 | 105 (56) | 163 (96)b | 18 (10) | 5 (3) | 19 (11)b | 36 (21)b |

NI, not isolated.

As this species was not isolated in 2006, the total number of samples was adjusted to calculate the average frequency (% positive).

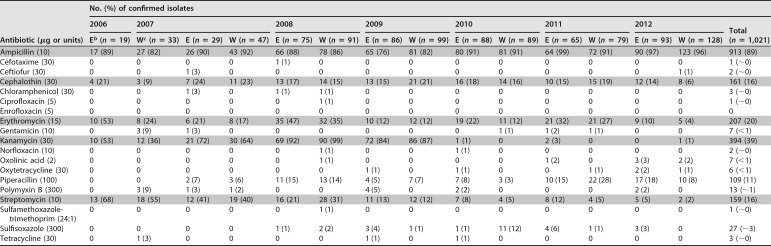

TABLE 2.

Comparison of antimicrobial resistance and frequencies detected in marine Vibrio spp. isolated from harvest sites at the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Canada during 2006 to 2012a

The five antibiotics contributing the most to AMR patterns and trends are highlighted.

bE, East (Altantic) coast.

cW, West (Pacific) coast.

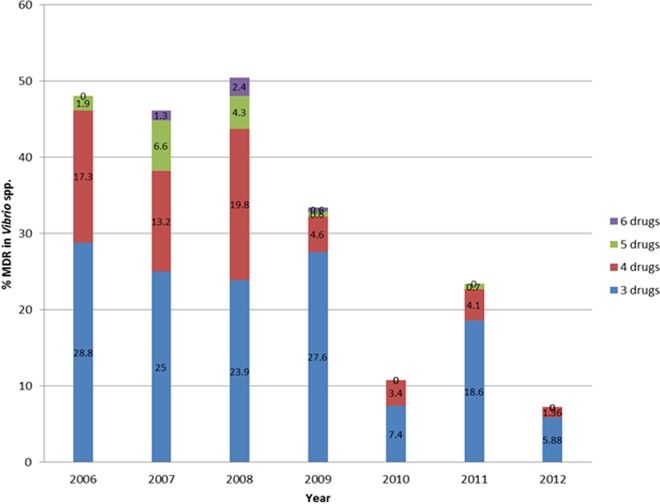

In addition to the major species, 114 strains belonging to other Vibrio spp. were identified (11% of total isolates) as follows: 28 V. vulnificus, 24 V. fluvialis, 7 V. cholerae, and 55 unidentified Vibrio spp. showing good identification at the genus level. All of these isolates, including the 7 V. cholerae isolates of marine origin, were tested for AMR and included in the analysis (Fig. 1 and 2). It should be noted here that the two major species (V. parahaemolyticus and V. alginolyticus) displayed similar AMR patterns by site and by year (data not shown). Many isolates (n = 294 [29%]) of Vibrio species were resistant to multiple antibiotics (MDR), but a declining trend in MDR was observed between 2008 and 2012 (Fig. 3). Resistance to 6 antibiotics was detected in three V. parahaemolyticus isolates, one (S191-10, British Columbia [BC], Pacific coast) in 2007 and two (S222-7, BC, Pacific coast, and S240-8, Quebec, Atlantic coast) in 2008, showing resistance to ampicillin, piperacillin, cephalothin, erythromycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin. Similarly, two V. alginolyticus isolates (S219-1, Nova Scotia [NS], Atlantic coast, and S230-5, BC, Pacific coast) showed resistance to the same six drugs in 2008, and another isolate (S280-5, NS, Atlantic coast) in 2009 displayed a different profile in which resistance to sulfisoxazole, tetracycline, and oxytetracycline was detected, while there was no resistance to piperacillin, erythromycin, or streptomycin. Resistance to ampicillin and kanamycin were common to all six isolates mentioned above. The MDR frequency of the halophilic Vibrio spp. declined from 60% in 2008 to 7% in 2012 (Fig. 3).

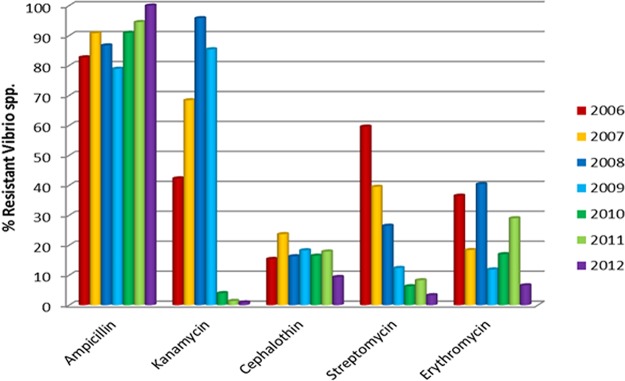

FIG 1.

The top five antibiotics to which resistance was detected among the halophilic Vibrio spp. isolated seasonally from Canadian molluscan shellfish, between 2006 and 2012. The reduction in frequency of resistance over time was significant for the aminoglycosides, kanamycin, and streptomycin.

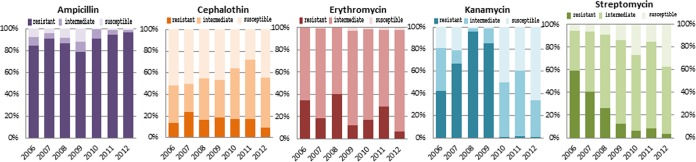

FIG 2.

Detection frequencies and complete susceptibilities of halophilic Vibrio spp. for the five leading antibiotics between 2006 and 2012. While resistance to kanamycin and streptomycin declined over time, susceptibility to the other drugs increased, as shown by the darkest (resistant), lighter (intermediate), and lightest (susceptible) colors in the bars.

FIG 3.

Multidrug resistance (to 3 or more antibiotics) detected among halophilic Vibrio spp. isolated from molluscan shellfish harvested in Canada between 2006 and 2012.

Resistance trend observed.

The top five antibiotics contributing to resistance profiles in 2006 were monitored during the period from 2006 to 2012, and a significant drop in resistance to the aminoglycosides, kanamycin and streptomycin, occurred among the Vibrio spp. (Fig. 1 and 2). Resistance to ampicillin was detected at a very high frequency, ranging from 76% to 99% with an average of 89% during the study period (Table 1), and the difference between east and west coast data on ampicillin detected yearly was not significantly different by a Student's t test (paired, two-tailed; P = 0.47) and the variance F-test (two-tailed; P = 0.44). Similar tests with other important antibiotics also showed no significant differences between east and west coast data, e.g., in the case of kanamycin and streptomycin, the P values were 0.42 and 0.37 (t test) and 0.93 and 0.82 (F test), respectively. Resistance to kanamycin showed an upward trend from 2006 to 2009, sharply declined thereafter, and remained low in frequency until the end of the study period in 2012 (Fig. 1 and 2). The frequency of resistance to streptomycin showed a decreasing trend during this period (Table 1). Among other clinically significant antibiotics, fluoroquinolones rarely contributed to AMR (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Since the predominant species (V. alginolyticus and V. parahaemolyticus) of Vibrio isolated from wild or cultured molluscs did not show any significant differences in their AMR patterns over the study period, it was presumed that the halophilic vibrios, including the lesser prevalent species, such as V. vulnificus, V. fluvialis, V. cholerae, and unidentified Vibrio spp., isolated from the same source during the study period would respond more or less similarly to the exposed challenges from contaminating antibiotics. Although protogenomic profiles of the species may vary to some extent, for our purpose, the genus Vibrio was used collectively as the indicator bacteria for determining the AMR pattern captured by the molluscan Vibrio species from the coastal environments of Canada.

The observed trend of a drop in AMR/MDR in molluscan Vibrio species between 2006 and 2012 could be an indication of the variability in the presence and levels of antibiotics in the Canadian estuaries. This trend might have resulted from unplanned stewardship practiced for aminoglycosides during the study period, due to a preference for other antibiotics or due to the easy availability and publicized effectiveness of new drugs on the market. The available data on defined daily doses (DDD) per 1,000 inhabitant-days for parenteral antibiotics purchased by hospitals in Canada from 2001 to 2011 were reported earlier (14), and the average DDD values for aminoglycosides was 0.05 in 2006 and dropped to 0.03 in 2011 (40% drop). Similar values for first-generation cephalosporins, including cephalothin, were between 0.11 and 0.12 (14). In the United States, 42 antibiotics belonging to 18 drug classes were approved for use in food-producing animals and actively marketed in 2009 (15). Kanamycin was absent from the list of five aminoglycosides (15), and our data showing a sudden drop in resistance to kanamycin from 2010 to 2012 coincides with the drop in drug usage in the United States, which shares coastal waters with Canada. Higher frequencies of resistance to streptomycin (85%) and kanamycin (57%) were also observed in halophilic vibrios isolated from seafood in Italy in 2001 (16), probably indicating that these two antibiotics were also used in Italy and the surrounding areas at that time. Another contemporary European (ESAC) surveillance study (8) reported that antibiotic use, defined by daily doses/1,000 inhabitants/day, was high in southern European countries (Greece, France, and Italy), which also supports the results from the Italian report (16). Therefore, the emergence of AMR/MDR appears to be directly proportional to drug usage in or around the region.

The combined presence of virulence markers and AMR in some Vibrio strains implies a potential emerging hazard for consumers of raw or undercooked seafood, particularly molluscan shellfish. It is difficult to establish whether those Vibrio strains that are both MDR and carry virulence genes are more hazardous for humans. A detailed analysis of strains and patients involved in Vibrio outbreaks will be useful in the future to generate a larger database to understand this complex issue.

A multipronged strategy consisting of infection control practices, surveillance, and antibiotic stewardship has been recommended to slow the increasing rate of AMR (17). D'Costa et al. (18) reported that the level and diversity of the environmental resistome are likely to be higher and much more extensive than those detected in their surveillance study using soil microorganisms. Therefore, it is possible that the discovery of novel antibiotics may not be a solution to the AMR issue, as, with time, AMR could also develop in bacteria exposed to these novel antibiotics. For example, the recent report by Briet et al. (19) confirmed the presence of a V. parahaemolyticus isolate from shrimp with MDR capacity, including NDM-1 carbapenemase activity. This carbapenemase activity was successfully transferred to Escherichia coli by conjugation; therefore, with time and the dissemination of this activity, some of the clinically important carbapenems may become ineffective. To combat AMR, a process can be used whereby one alternates the usage of an antibiotic, or a class of antibiotics, in a cyclic manner. As a result, the targeted antibiotics can be made effective for periods of time separated by phases of complete prohibition, which would need to be determined more precisely following more objective studies and supportive data from other temperate regions of the world. Thus, a strategy of cyclic regulation of medically important drugs could possibly be used for antibiotic stewardship programs at the international level.

This study has presented, for the first time, a detailed analysis of the AMR profiles of molluscan Vibrio spp. isolated from molluscs grown in Canadian estuaries. As a result, the data presented here will be a useful addition to the repository of data on AMR resistance in Canada from the surveillance of inland farms and retail outlets (11, 13). The data will also provide a solid foundation for future studies on AMR trends and patterns in pathogenic Vibrio spp. This is important, as globally, an increase in cases of vibriosis has been observed, and with global warming, cases are expected to further increase in the future. The AMR data we collected in this study may also be useful in guiding policy development for the nonmedical use of antibiotics in farms close to estuaries. In addition, a detailed examination of AMR patterns from clinical strains of V. parahaemolyticus isolated during the same period will be useful in exploring if the same declining AMR trends observed for some of the antibiotics, e.g., kanamycin and streptomycin, in food isolates has also occurred with the clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 1,021 Vibrio isolates were used, including V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus, V. fluvialis, V. alginolyticus, and other Vibrio spp. with good identification at the genus level, obtained from wild or cultured molluscs, such as oysters, mussels, or clams. The molluscs were harvested from sites on both coasts of Canada between May and October of each year from 2006 to 2012. Samples were collected from the same harvest sites every year during the study period. Live molluscs were shipped under refrigerated conditions (4°C to 10°C) to the laboratory and processed the same day. Briefly, 10 to 20 molluscs were shucked and homogenized in a blender to obtain approximately 100 to 200 g of smooth tissue, of which 50 g was mixed with 450 ml alkaline peptone water ([APW] pH 8.4) and then equilibrated at room temperature (approximately 23°C) for 60 to 75 min to resuscitate bacterial function. In-house procedures were developed for the identification, isolation, and characterization of the isolates on the basis of standard methods (20, 21). The presence/absence of virulence markers, such as thermostable direct hemolysin (tdh) and tdh-related hemolysin (trh), were confirmed by PCR (20, 22, 23). Standard strains from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA), i.e., V. parahaemolyticus ATCC 17802, V. alginolyticus ATCC 17749, and V. vulnificus ATCC 27562, were used as positive controls for PCR and/or phenotypic identification of the strains on selective media. Standard strains of other bacteria (E. coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853) were used as controls in the antimicrobial susceptibility tests to verify the growth and inhibition zones for each of the antibiotics, as suggested by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (24).

Microbiological analysis.

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates were determined by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method (25) on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates. In brief, overnight isolated colonies of the test strains from Columbia blood agar (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hants, UK) supplemented with 5% defibrinated horse blood were resuspended in tryptic soy broth with 2% NaCl ([TSB-2N] pH 8.5), while the control (nonvibrio) strains, grown similarly, were resuspended in Trypticase soy broth ([TSB] pH 7.4). All suspensions were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ottawa) and evenly spread on MHA by using sterile cotton swabs. Overall, 19 antimicrobial discs (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK), each containing a known amount of an antibiotic, were laid on a lawn of the bacteria on MHA plates and incubated at 35°C for 18 to 24 h, according to the CLSI protocol. The antimicrobial classes, antibiotics, and the concentrations of the drugs were as follows: the aminoglycosides gentamicin (GEN), 10 μg; kanamycin (KAN), 30 μg; and streptomycin (STR), 10 μg; the cephems cephalothin (CEF), 30 μg; cefotaxime (CTX), 30 μg; and ceftiofur (CTF), 30 μg; the folate pathway inhibitor sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (24:1) (SXT), 25 μg; the lipopeptide polymyxin B (PMB), 300 U; the macrolide erythromycin (ERY), 15 μg; the penicillins ampicillin (AMP), 10 μg; and piperacillin (PIP), 100 μg; the phenicol chloramphenicol (CHL), 30 μg; the quinolones ciprofloxacin (CIP), 5 μg; enrofloxacin (ENO), 5 μg; norfloxacin (NOR), 10 μg; and oxolinic acid (OX), 2 μg; the sulfonamide sulfisoxazole (SF), 300 μg; and the tetracyclines tetracycline (TET), 30 μg; and oxytetracycline (OT), 30 μg. The isolates were reported as sensitive, resistant, or of intermediate susceptibility to each antibiotic on the basis of inhibition zone size measurements, as recommended by CLSI (24). In the absence of definitive standards of Vibrio species for AMR testing, zone diameters of bacterial standard strains, such as E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 25923, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, were used for quality assurance of the antibiotics and reliability of the protocol.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests (Student's t tests and variance ratio F tests) were used to determine if the AMR data sets from the east and west coasts of Canada were different or similar. The F test was chosen to find out the significance of variances between data sets, while the t test analyzed the association between the east and west coast data related to specific antibiotics. Both tests were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010, and a P value of ≤0.05 was defined to indicate significant differences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded (A-base) by Health Canada in support of Canada's Food Safety Programs.

We thank Franco Pagotto and Sandeep Tamber of the Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Health Canada, for peer-reviewing the manuscript and offering helpful comments. We also thank the staff from the media laboratory (Andrew, Samia, and Matt) for preparing all the testing materials and Mahdid Meymandy, Xiaodong Wan, and Rachel Adm for technical assistance.

We declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morar M, Wright GD. 2010. The genomic enzymology of antibiotic resistance. Annu Rev Genet 44:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WW, Schwarz C, Froese D, Zazula G, Calmels F, Debruyne R, Golding GB, Poinar HN, Wright GD. 2011. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477:457–461. doi: 10.1038/nature10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hocquet D, Muller A, Bertrand X. 2016. What happens in hospitals does not stay in hospitals: antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospital wastewater systems. J Hosp Infect 93:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Canada. 2016. Water pollution, wastewater, and wastewater systems effluent regulations. Environment and Climate Change, Government of Canada, Gatineau, QC, Canada: https://www.ec.gc.ca/eu-ww/ Accessed 29 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies J, Davies D. 2010. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. 2007. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. CDC, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf Accessed 29 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goossens H. 2009. Antibiotic consumption and link to resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 15 (Suppl3):12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. 2015. Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system: manual for early implementation. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/188783/1/9789241549400_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance. Global report on surveillance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government of Canada. 2014. Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) 2012 Annual Report. Chapter 2. Antimicrobial resistance. Public Health Agency of Canada, Guelph, Ontario, Canada: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/HP2-4-2012-2-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of Canada. 2015. Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) 2012 Annual Report. Chapter 3. Antimicrobial use in animals. Public Health Agency of Canada, Guelph, Ontario, Canada: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/aspc-phac/HP2-4-2012-3-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avery BP, Parmley EJ, Reid-Smith RJ, Daignault D, Finley RL, Irwin RJ. 2014. Canadian integrated program for antimicrobial resistance surveillance: retail food highlights, 2003–2012. Can Commun Dis Rep 40(Suppl 2):29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finley R. 2014. Antibiotic purchasing by Canadian hospitals, 2007–2011. Can Commun Dis Rep 40(Suppl 2):23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2014. 2009 summary report on antimicrobials sold or distributed for use in food-producing animals. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/AnimalDrugUserFeeActADUFA/UCM231851.pdfGoogleScholar. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottaviani D, Bacchiocchi I, Masini L, Leoni F, Carraturo A, Giammarioli M, Sbaraglia G. 2001. Antimicrobial susceptibility of potentially pathogenic halophilic vibrios isolated from seafood. Int J Antimicrob Agents 18:135–140. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(01)00358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartlett JG, Gilbert DN, Spellberg B. 2013. Seven ways to preserve the miracle of antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 56:1445–1450. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Costa VM, McGrann KM, Hughes DW, Wright GD. 2006. Sampling the antibiotic resistome. Science 311:374–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1120800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briet A, Helsens A, Delannoy S, Debuiche S, Brisabois A, Midelet G, Granier SA. 22 May 2018. NDM-1-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from imported seafood. J Antimicrob Chemother doi: 10.1093/jac/dky200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee SK, Farber JM. 2017. Detection, enumeration, and isolation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus from seafood: development of a multidisciplinary protocol. J AOAC Int 100:445–453. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.16-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaysner C, DePaola A Jr. 2004. Bacteriological analytical manual, Chapter 9. Vibrio U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD: http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/ucm070830.htm Accessed 3 Aug 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bej AK, Patterson DP, Brasher CW, Vickery MC, Jones DD, Kaysner CA. 1999. Detection of total and haemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tlh, tdh, and trh. J Microbiol Methods 36:215–225. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishibuchi M, Kaper JB. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of the thermostable direct hemolysin gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol 162:558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria; 3rd ed CLSI M45. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC, Turck M. 1966. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol 45:493–496. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/45.4_ts.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]